This is the general methods describing paper of a cross-sectional study that aims to detect the prevalence of major mental disorders in Andalusia (Southern Spain), and their correlates or potential risk factors, using a large representative sample of community-dwelling adults.

Materials and methodsThis is a cross-sectional study. We undertook a multistage sampling using different standard stratification levels and aimed to interview 4518 randomly selected participants living in all 8 provinces of the Andalusian region utilising a door-knocking approach. The Spanish version of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, a valid screening instrument ascertaining ICD-10/DSM-IV compatible mental disorder diagnoses was used as our main diagnostic tool. A large battery of other instruments was used to explore global functionality, medical comorbidity, personality traits, cognitive function and exposure to psychosocial potential risk factors. A saliva sample for DNA extraction was also obtained for a sub-genetic study. The interviews were administered and completed by fully trained interviewers, despite most tools used are compatible with lay interviewer use.

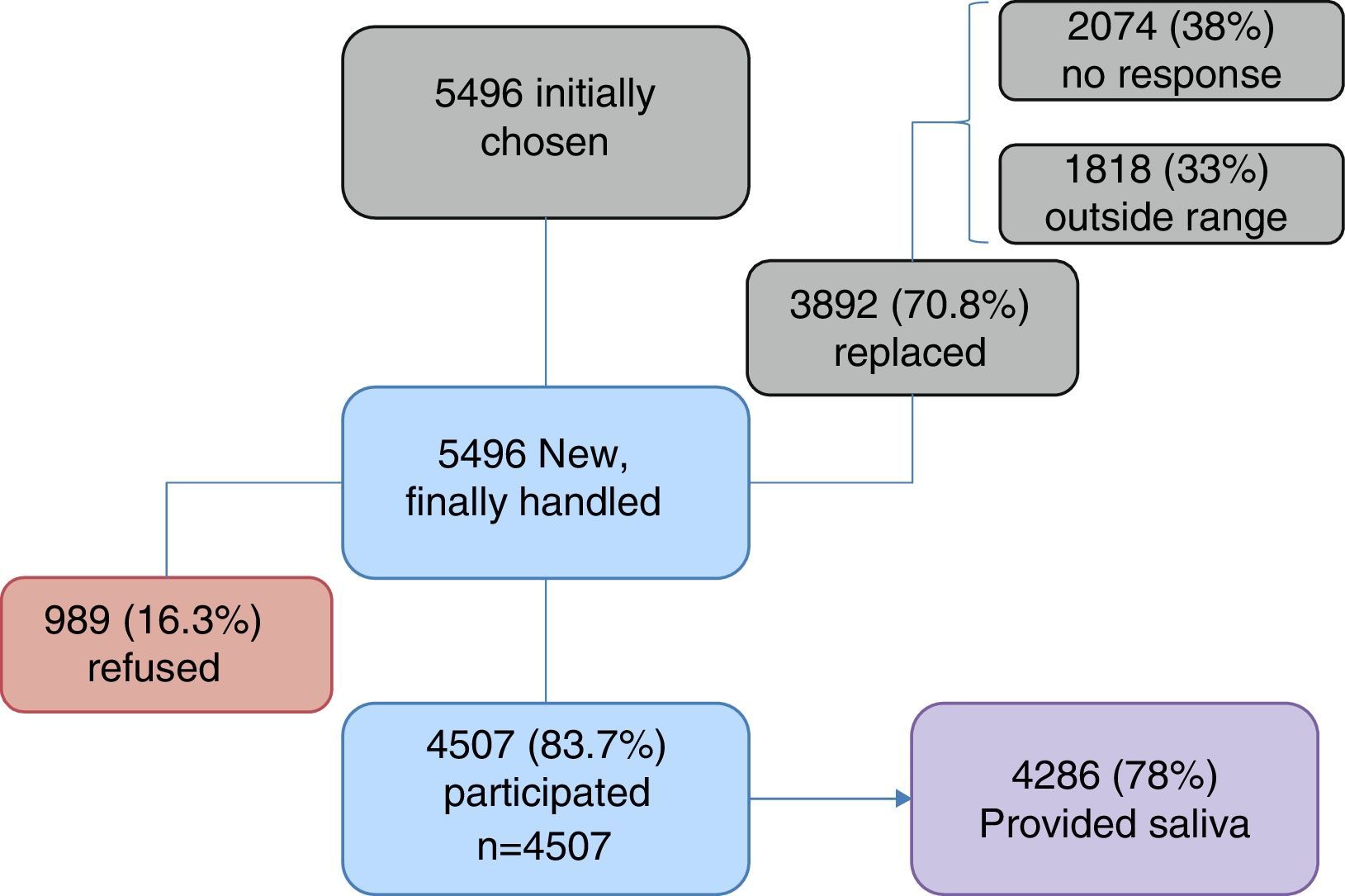

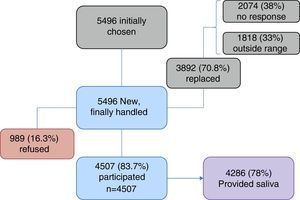

ResultsA total of 3892 (70.8%) of 5496 initially attempted households had to be substituted for equivalent ones due to either no response (37.7%) or not fulfilling the required participant quota (33%). Thence, out of 5496 eligible participants finally approached, 4507 (83.7%) agreed to take part in the study, completed the interview and were finally included in the study (n=4507) and 4286 (78%) participants also agreed and consented to provide a saliva sample for DNA study. On the other hand, 989 (16.3%) approached potential participants refused to take part in the study.

DiscussionThis is the largest mental health epidemiological study developed in the region of Spain (Andalusia). The response rates and representativeness of the sample obtained are fairly high. The method is particularly comprehensive for this sort of studies and includes both, personality and cognitive assessments, as well as a large array of bio-psycho-social risk measures.

El presente artículo describe la metodología general de un estudio transversal cuyo principal objetivo consiste en la detección de la prevalencia de los principales trastornos mentales en Andalucía, y el estudio de sus correlatos o posibles factores de riesgo mediante una amplia muestra representativa de adultos que vive en la comunidad.

Materiales y métodosEste es un estudio transversal en el que desarrollamos un muestreo de varias fases utilizando distintos niveles de estratificación habituales y en el que teníamos como objetivo entrevistar a 4.518 participantes seleccionados al azar y representativos de las 8 provincias de la comunidad andaluza, con un enfoque de «llamada a la puerta». Como principal herramienta diagnóstica se utilizó la versión española de la entrevista neuropsiquiátrica internacional MINI, un instrumento válido de detección para el establecimiento de diagnósticos de trastorno mental compatibles con los criterios CIE-10/DSM-IV. Asimismo, se empleó una amplia batería de instrumentos para explorar la funcionalidad global, la comorbilidad médica, las características de la personalidad, la función cognitiva y la exposición a posibles factores de riesgo psicosocial. También se obtuvo una muestra de saliva para extraer ADN para un estudio de asociación genética. Entrevistadores entrenados llevaron a cabo las entrevistas, a pesar de que la mayoría de las medidas son compatibles con entrevistadores legos.

ResultadosDe los 5.496 hogares seleccionados inicialmente, el 70,8% (3.892) tuvieron que sustituirse por falta de respuesta (37,7%) o por no incluir a ninguna persona que cumpliese las características requeridas (33%). Así, de las nuevas 5.496 personas, a las cuales finalmente se accedió, 4.507 (83,7%) consintieron participar, completaron la entrevista y se las incluyó finalmente en el estudio (n=4.507), mientras que 4.286 (78%) también proporcionaron una muestra de saliva. Por su parte, 989 (16,3%) rechazaron participar.

DiscusiónSe trata del estudio de epidemiología de salud mental más amplio desarrollado en la comunidad autónoma más grande y poblada de España (Andalucía). Las tasas de respuesta y representatividad de la muestra son bastante altas. El método empleado es muy completo para este tipo de estudios e incluye tanto valoraciones de personalidad (rasgos y trastorno) como valoración cognitiva, así como un amplio abanico de medidas de riesgo biopsicosocial.

The latest Global Burden of Disease Study by the World Health Organisation1 states that mental disorders are the main cause of years lost through disability. Although the contribution of mental disorders to years of life lost through premature mortality is relatively small, possibly because death is coded as the physical cause of associated morbidity, the World Health Organisation report shows that the global burden attributable to mental disorders increased by nearly 40% between 1990 and 2010. It has also been stated that mental and behavioural disorders are the third general source of disability in high income countries.2 A major portion (40%) of this burden is exclusively due to depression, which has also been identified as one of the main causes of years lost through disability in Spain in the latest report by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.3

In the light of the above considerations, mental disorders represent a huge challenge to public health. The estimation of the prevalence of mental disorders in regions without previous data, as is the case in Andalusia, and the identification of possible risk factors are of the utmost importance for the planning of services and the implementation of preventative measures.

The PISMA-ep study was conducted in the 8 provinces of Andalusia, the largest Spanish autonomous community with almost 9 million inhabitants according to the census, representing almost a fifth of the total Spanish population. This article describes the methodological aspects and the protocol of the PISMA-ep study, which is the first epidemiological study of mental disorders and their associated factors to be carried out using a sample which is representative of the entire Andalusian population. The PISMA-ep study was an initiative of the Integral Mental Health Plan for Andalusia (PISMA), through which the Andalusian Health Service aims to assess psychiatric comorbidity and its correlates in Andalusia to obtain data for future planning. The main aims of the PISMA-ep study were: (1) to estimate the transversal and lifelong prevalence of frequent mental disorders; (2) to explore the social, psychological and genetic factors associated with these mental disorders, and (3) to study a large transversal cohort of patients which could constitute the basis for future prospective follow-up or for prospective studies.

MethodsDesign and frameworkThis is a transversal study of a broad stratified sample representative of Andalusian adults who live in the community, aged between 18 and 75. All the provinces of the Andalusian autonomous community were included. The study was partially financed with a subsidy from the Department of Economy, Innovation and Science of the Regional Government of Andalusia (10-CTS-6682). The main group of authors (JC, IR, MRB and BG) originally designed the study which was subsequently optimised with contributions from other co-authors. A public bid was then launched for companies specialising in health surveys, aimed at developing the sample and the fieldwork interviews. In this case, a local survey company which had conducted extensive health-related surveys in Andalusia won the bid, formed the sample and collected data in the participants’ homes. The study interviews were conducted between 2013 and 2014, during a period which lasted almost one year.

SampleA sample was created in several stages using different levels of stratification, i.e. (1) proportional stratification which took into account geographical areas of Western and Eastern Andalusia; (2) a second level of stratification which considered city size in each geographical area. The categories within this level were: urban (over 10,000 inhabitants), intermediate (between 2001 and 10,000 inhabitants) and rural (up to 2000 inhabitants); (3) we also stratified each sample area of the 8 provinces of Andalusia, and finally (4) within each province a simple random method was used to select between one and 5 municipal entities (towns) for each location size (urban, intermediate or rural). Following this, and using the same simple random method of assignation, and bearing in mind age and gender quotas, the census sections and the districts of each locality chosen, the final sample were selected. Final sample units are therefore people of both sexes aged between 18 and 75, who were interviewed if they lived in houses in predetermined street routes within the census districts and sections previously randomly identified. One in every 4 consecutive homes was visited.

Calculation of sample sizeEstimations were made regarding sample power as a priority to determine target sample size, for the purpose of calculating a 2% prevalence with ±0.5% precision, confidence intervals of 95% and for an estimated effect size of 1.5. This calculation represented a target sample size of 4518.

Pilot phaseA pilot phase was carried out with the first 20 interviews in each of the 8 Andalusian provinces, totalling 160 interviews. In this phase the suitability of all the questions was assessed, as was the method of sample selection and general willingness to provide a saliva sample. Following this, the redaction or formulation of several questions was slightly altered to match the local Andalusian diction to ensure intelligibility (i.e. questions B1, J1 and K1 of the MINI questionnaire). The changes were unimportant and consensus was reached by a group of experts (JC, BG and EV) to endorse the modifications for item validity. The pilot phase of the 2 sample methods and saliva sample did not differ in any way from the scheduled procedures.

Participant replacement methodsIf there was no response after 2 consecutive calls at a house, it was visited on 2 subsequent occasions at different times of the day. If there was no immediate response after this, the interviewer went to the following house which had not yet been called on in the pre-determined route. If necessary, this process was repeated until an eligible participant was finally found. When a house responded, the first person available in the home, within the age and gender ranges for the route, was invited to participate. If the person refused to participate in the study, a replacement was made by visiting the next available house, and asking a person to participate who fell into the same age and gender brackets as the person who had previously refused.

Evaluation and risk criteriaSociodemographic data (Barona Index)The IQ of each participant was calculated with a Spanish version of the Barona et al. formula,4 developed by Bilbao and Seisdedos.5 This formula uses the sociodemographic variables of age, gender, educational level, urban status and geographic region to estimate the participant's IQ.

Family psychiatric history (Family Interviews for Genetic Studies)Spanish versions of the general screening questions were used together with the symptom confirmation list from the Family Interviews for Genetic Studies in order to gain diagnostic information regarding all the known ascendants of each participant, with particular emphasis on first-degree relatives.6 In our study, this information was obtained from each participant, who acted as the source of information on his or her own family. The Family Interviews for Genetic Studies enabled us to detect psychiatric cases within the family and a better calculation was obtained with regards to depression, mania, alcoholism, drug addiction, psychosis or paranoid/schizoid/schizotypal personality disorder.

The Mini Neuropsychiatic Interview7The Mini-International Neurosphychiatric Interview (MINI) is a brief diagnostic structured interview on Axis I psychiatric disorders compatible with DSM-IV and CIE-10. Its algorithms and question formulations are similar to those of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. The MINI is divided into modules identified by letters corresponding to diagnostic categories. At the beginning of each module (except for psychotic disorders), a detection question (or questions) corresponding to the main criteria of the disorder are shown in a grey box. At the end of each module the diagnostic box(es) enabled the clinician to indicate if the diagnostic criteria were met or not. In the majority of diagnostic sections one of 2 detection questions were used to rule out the diagnosis when the response was negative.

MINI thus generated 16 different types of Axis I mental disorder diagnoses. Each diagnostic section began with one or 2 detection questions which filtered the need to continue with more diagnostic questions within each section if detection were positive. Participants who were ruled out as negative did not complete the whole diagnostic section and were not considered as cases for that particular diagnostic section. Those who were selected as possible cases were requested to complete the whole series of questions in that section, whether they fulfilled the diagnostic criteria or not. The MINI interview has been used in many different cultures8–10 and has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties in each language with kappa values concordant with other interviews, such as the Composite International Diagnostic Interview or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders, Patient Edition, which in the majority of cases is very much above the value of 0.7. A high degree of inter-evaluator reliability has also been demonstrated, together with correct sensitivity and a low rate of false positives when used, as in this case, on the healthy population living in the community.

Childhood experiences11We collected data on 3 types of mistreatment people could have suffered from during childhood, assessing them with the abbreviated Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: psychological and physical mistreatment and sexual abuse. These questions were proven to have appropriate test–retest reliability in the context of the Predict-D study.12,13 The score for each item on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire ranged from 1 to 5, depending on the degree to which participants agreed with a statement. However, in this study we separated emotional from physical and sexual abuse to simplify the comparison of findings with those recorded from previous studies. Our groups were defined as follows: the emotional group included participants who had suffered from some type of emotional mistreatment only and had not suffered any other type of child abuse, either physical or sexual. The physical mistreatment group included those with a history of physical mistreatment in childhood, with or without emotional mistreatment but in either case without any sexual abuse. The last group were those who had been sexually abused as children, with or without emotional or physical mistreatment as well. From the 3 types of mistreatment the variable “any type of childhood mistreatment” was obtained which was also used in analysis. This variable refers to the participants who suffered from at least one of these forms of mistreatment.

Threatening life events14This is a validated reference list of a subgroup of 12 categories of life events which had occurred in the past 6 months, with considerable long term contextual risk. The majority of events shown here with moderate or marked risk scores, stem from 12 categories of events: serious illness or injury of the individual; serious illness or injury of close family members; death of a first-grade family member (including spouse or child); death of a second-grade family member/friend; separation of a marriage; termination of a stable relationship; problems with a close friend, family member or neighbour; unemployment/dismissal; serious financial difficulties; problems with the police and the law; loss or theft of a valuable object.

Health questionnaire15General health was assessed by means of the SF-12 questionnaire, a subgroup of 12 items of the generic SF-36 health survey. There are 2 summary scores for the following components: Physical Component Summary Score and the Mental Health Component Summary Score during the last 4 weeks.15

Social support16This list assesses what people think about their family and friends. The questions are split into 3 groups: relationship with the family and friends, relationship with spouse or partner and ability to maintain relationships in general.

Tobacco consumption (Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence)This is a standard tool for assessing the intensity of physical addiction to nicotine.17 This test is designed to provide an ordinal measurement of nicotine addiction related to cigarette consumption. It contains 6 items which assess the number of cigarettes consumed, compulsion and addiction. Responses to “Yes/no” items are given a score from 0 to 1 and the multiple choice items responses are calculated from 0 to 3. The items are added together to obtain a total score of 0–10. The higher the total Fagerström score, the more intense the physical addition of the patient to nicotine. A total score was obtained by adding up all the scores and then referring to participants as having a nicotine addiction (from 0 to 5 points) or high nicotine dependency (from 6 to 10 points).

Alcohol consumption (CAGE questionnaire for alcoholism)18The CAGE questionnaire consists of 4 simple questions which are easy to remember, which have played a major role in the detection of alcoholism. The 4 simple questions are: have you ever (1) felt the need to reduce your consumption; (2) been upset by criticism regarding the way you drink; (3) felt guilty about your consumption and (4) felt the need for a drink first thing in the morning (on opening your eyes) to calm your nerves or lessen your hangover? CAGE is considered a detection technique validated with a study which determines that scores ≥2 lead to specificity of 76% and sensitivity of 93% for identifying excessive consumption and a specificity of 77% and sensitivity of 91% for identification of alcoholism.19

Screening Scale for Cognitive Impairment in psychiatry20The Screening Scale for Cogitative Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP) was designed to detect cognitive deficiencies in several psychotic and affective disorders. It may be administered without the need for additional equipment (just pen and paper) and can be completed in 15min. There are three alternative forms of the scale to help in repetitive tests and reduce the effects of learning to a minimum. The SCIP includes an Immediate Verbal Learning Test, a Working Memory Test, a Verbal Fluency Test, a Delayed Verbal Learning Test and a Processing Speed Test. The original version of the SCIP is in English,21 and the justification, development and translation of the Spanish adaptation (SCIP-S) were described in a previous publication.22 The SCIP-S has been proven to contain the appropriate psychometric properties for detecting cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia23 and bipolar type I disorder.24

Subscale of Psychotic Symptoms (SCID-I/P)23The structured clinical interview for DSM Axis I Disorders [SCID-I]) is divided into 2 standard editions: the patient edition–SCID-I/P, for psychiatric patients and the edition which is not for the patient–SCID-I/NP, for use in other matters. The SCID-I/P contains a module called C which examines the existence of psychotic disorders and symptoms, and we use this as a support and double control tool to better profile the existence of these psychotic experiences if the psychoses section in the MINI is considered limited and rather superficial in identifying psychotic phenomena.

General and social functioningGeneral functioning was measured with the Global Assessment of Functioning,25 the Objective Social Outcomes Index26 and the Personal and Social Performance Scale.27 The Global Assessment of Functioning comprises a single item, the patient's general activity, classifying it on a scale of 100 (good activity) to 1 (clear expectation of death). The Objective Social Outcomes Index assesses patient functions. It is composed of 4 elements: employment, accommodation situation, partner/family and friends. The first 2 are classified from 0 to 2 and the other 2 from 0 to 1. The general score is the sum of the scores for each item, up to a maximum of 6. A higher score means better functioning. The Personal and Social Performance Scale measures social functioning in 4 areas: socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, personal care, and disturbing and aggressive behaviour (the higher the score the better the functioning). The scores on this scale range from 1 to 100, with a seriousness scale of 6 points for each area. The higher the scores, the better personal and social functioning.

Standardised Assessment of Personality-Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)28This scale detects personality disorders comprised of 8 elements. A dimensional score is awarded from 0 to 8, representing a person's probability of having a personality disorder in general. In psychiatric patients, a score of 3 or above is sensitive and specific as a measure of the existence of a personality trait according to the structured clinical interview of the DSM-IV.29 The Standardised Assessment of Personality-Abbreviated Scale is a combination of markers created to cover different areas of personality.

Personality traits: neuroticism and impusiveness30Two personality traits, neuroticism-anxiety and impulsive-sensation seeking were assessed using the corresponding sections of the Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire.30 In this questionnaire there are 5 personality scales: (1) “impulsive-sensation seeking” which is described as a tendency to act quickly on impulse and without planning, often in response to a need for sensations and emotion, change and novelty; (2) “Neuroticism-anxiety” described as a tendency to be tense and worried, over-sensitive to criticism, easily upset and obsessively indecisive; (3) “Aggression-hostility” described as a tendency to express verbal aggression and show brusqueness, lack of consideration, a vengeful nature, bitterness, rage and impatient behaviour; (4) “Sociability” described as the tendency to interact with others, be at ease with others and intolerance of social isolation and (5) “Activity” described as a tendency to remain active, prefer a challenging task and be impatient or restless when having nothing to do.

Questionnaire on medical problemsThis is a reference list of medical conditions, frequently used in national health surveys,31 which includes 21 specific pathological processes referred to by the patients themselves, such as diabetes, migraine, high blood pressure, stroke and cancer, among others.

Information on medicationThis was assessed with a reference list which included 16 frequently prescribed medicines, such as antibiotics, analgesics, vitamins, contraceptives and anti-depressants, among others.

Information on exerciseBriefly assessed with 3 questions which cover the type of exercise the person practises, the number of hours per week and the intensity of the exercise.

Anthropometric measuresThe height and weight of each patient were recorded. The body weight mass was estimated as weight in kilograms divided by height in square metres (weight [kg]/height [m2]). The circumference of waist and hip were measured with a metric tape. The circumference of the waist was measured at the widest part of the buttocks and the circumference of the hip at the navel or just above it. Both measurements were repeated 3 times and the mean obtained.

Biological sampleA biological sample was obtained from each participant with an Oragene® saliva DNA (OG-500; DNA Genotek Inc.) collection kit. DNA was extracted using the Oragene® saliva collection kit protocol according to the manufacturer's instructions. The original DNA samples were prepared to be stored at −80°C in matrix plaque format. DNA concentration was measured by absorption using the Infinite® M200 PRO multimode reader (Tecan, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Gender-based violenceThe women were asked whether their partner had physically (hitting, slapping, pushing, etc.), psychologically (threats, insults, humiliations, etc.) or sexually (forcing them to have sexual relations) mistreated them. These 3 questions used by this group in previous studies,32 were highly intelligible and acceptable, and there were 3 possible answers: “often”, “at times” and “never”. A woman was considered to have been physically mistreated if she responded “often” or “at times” to any of the 2 questions on physical and/or sexual violence, and that she had been psychologically mistreated if she answered in the affirmative to the question on psychological violence.

Green Paranoid Thought Scales (GPTS)The Green Paranoid Thought Scales (GPTS) is a tool which was developed for the assessment of delusional thoughts and is adapted to today's widely accepted definition of paranoia.33 It can be used in both clinical and community groups and is sufficiently precise to detect subtle clinical changes. The Spanish version validated by our group provided sufficient proof of reliability and validity.34 The GPTS comprise 32 items to which a score is given using a Likert type scale of 5 points (from 1 [not at all] to 5 [totally]). Items are grouped into two 16 item subscales. Subscale A assesses socially based ideas whilst subscale B assesses persecutory thoughts. Scores in each subscale range between 16 and 80 points, and the highest score reflects a higher level of delusional thought. Each subscale must be individually administered and the results in both may be added up to reach a global paranoia score. The GPTS is a self-applied tool and takes approximately 10–15min to complete.

Interviewer training and reliabilityAll interviewers attended a training course for one week imparted by the main researcher (JC) and demonstrated they had sufficient knowledge of interview techniques and all the protocol scales and inventories, the majority of which had originally been designed so that they could be distributed by interviewers. Teaching techniques included talks, roleplay between interviewers and the assessment of video recording of interviews conducted by experts (JC and IIC) with volunteers. However, all the tools used had been previously validated and had demonstrated sufficient inter-evaluating and intra-evaluating credibility, together with the other psychometric properties. Cognitive assessment through the use of the SCIP required a particularly intensive half-day training, and there was a further specific half-day training on the identification of psychotic phenomena with the MINI and module C of the SCID-I. The inter-evaluating credibilities of the tools among interviewers after training sessions were high and scores according to kappa calculations were recorded in the results section. No test–retest reliability calculations were made.

Quality control of dataAfter the interview, all of the interviewers checked that the protocol questionnaires had been completed. Within a time scale of 5 working days after the interview, one interviewer coordinator per province checked twice that all the questionnaires had been completed and also reviewed the quality of the data completed by the provincial interviewers (approximately from 5 to 10 per province) and looked locally and rapidly for errors in order to improve data quality where necessary. The coordinator of each province randomly put 15% of the questionnaires from their province into a computer file. A general data central administrator subsequently entered all the data and compared those that had been inserted twice, accepting an error rate of up to 1%.

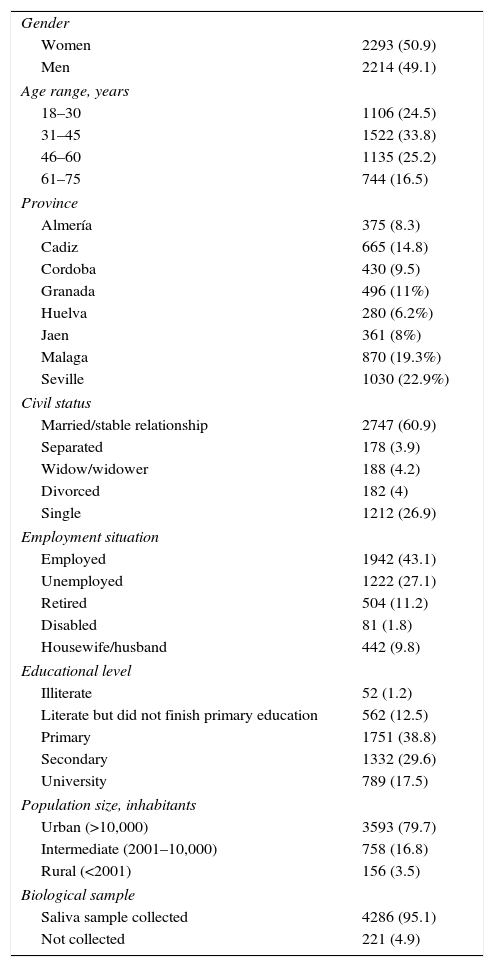

ResultsSample size and characteristicsA total sample of 4507 participants was finally included in the study. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample in detail. To sum up, 2214 men (49.1%) and 2293 women (50.9%) participated. Their mean age was 42.8 years (SD=15.22) and their average estimated intelligence quotient was 109.2. There were 1038 participants in Seville, the most highly populated province and 280 in Huelva, the least populated province, with intermediate samples in the other 6 provinces (Table 1).

Sample characteristics.

| Gender | |

| Women | 2293 (50.9) |

| Men | 2214 (49.1) |

| Age range, years | |

| 18–30 | 1106 (24.5) |

| 31–45 | 1522 (33.8) |

| 46–60 | 1135 (25.2) |

| 61–75 | 744 (16.5) |

| Province | |

| Almería | 375 (8.3) |

| Cadiz | 665 (14.8) |

| Cordoba | 430 (9.5) |

| Granada | 496 (11%) |

| Huelva | 280 (6.2%) |

| Jaen | 361 (8%) |

| Malaga | 870 (19.3%) |

| Seville | 1030 (22.9%) |

| Civil status | |

| Married/stable relationship | 2747 (60.9) |

| Separated | 178 (3.9) |

| Widow/widower | 188 (4.2) |

| Divorced | 182 (4) |

| Single | 1212 (26.9) |

| Employment situation | |

| Employed | 1942 (43.1) |

| Unemployed | 1222 (27.1) |

| Retired | 504 (11.2) |

| Disabled | 81 (1.8) |

| Housewife/husband | 442 (9.8) |

| Educational level | |

| Illiterate | 52 (1.2) |

| Literate but did not finish primary education | 562 (12.5) |

| Primary | 1751 (38.8) |

| Secondary | 1332 (29.6) |

| University | 789 (17.5) |

| Population size, inhabitants | |

| Urban (>10,000) | 3593 (79.7) |

| Intermediate (2001–10,000) | 758 (16.8) |

| Rural (<2001) | 156 (3.5) |

| Biological sample | |

| Saliva sample collected | 4286 (95.1) |

| Not collected | 221 (4.9) |

Data expressed as n (%).

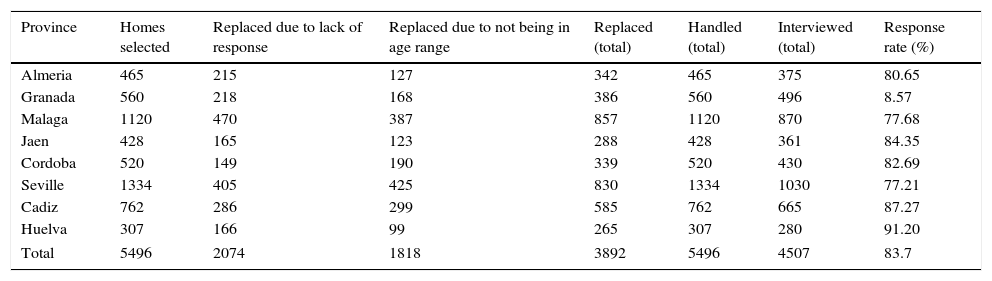

The homes originally selected which did not respond after 4 different attempts or did not have any member within the set age and gender range were replaced by the next available person within the predetermined route. A total of 70.8% of homes initially selected had to be replaced. Table 2 contains information by province of the homes where we initially tried to carry out interviews, those which were replaced and finally those which were handled with the response rates by province. 37.7% (2074) of homes chosen did not respond after all the attempts made and they had to be replaced due to a lack of response. Another third (33%) of homes originally chosen (1818) were replaced because there was nobody within the age, gender and educational range who matched in the area. In total, 3892 homes (70.8%) were replaced by other equivalent ones. As a result, 5496 homes were finally used for the study, 4507 agreed to participate in it and completed the interview (83.7% of those handled), and 4286 participants (95.1% of participants and 78% of those originally chosen) agreed and gave their consent to provide a saliva sample for the DNA study. Fig. 1 shows the response and replacement rates of the PISMA-ep cohort.

Response rates and homes chosen, replaced, handled.

| Province | Homes selected | Replaced due to lack of response | Replaced due to not being in age range | Replaced (total) | Handled (total) | Interviewed (total) | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeria | 465 | 215 | 127 | 342 | 465 | 375 | 80.65 |

| Granada | 560 | 218 | 168 | 386 | 560 | 496 | 8.57 |

| Malaga | 1120 | 470 | 387 | 857 | 1120 | 870 | 77.68 |

| Jaen | 428 | 165 | 123 | 288 | 428 | 361 | 84.35 |

| Cordoba | 520 | 149 | 190 | 339 | 520 | 430 | 82.69 |

| Seville | 1334 | 405 | 425 | 830 | 1334 | 1030 | 77.21 |

| Cadiz | 762 | 286 | 299 | 585 | 762 | 665 | 87.27 |

| Huelva | 307 | 166 | 99 | 265 | 307 | 280 | 91.20 |

| Total | 5496 | 2074 | 1818 | 3892 | 5496 | 4507 | 83.7 |

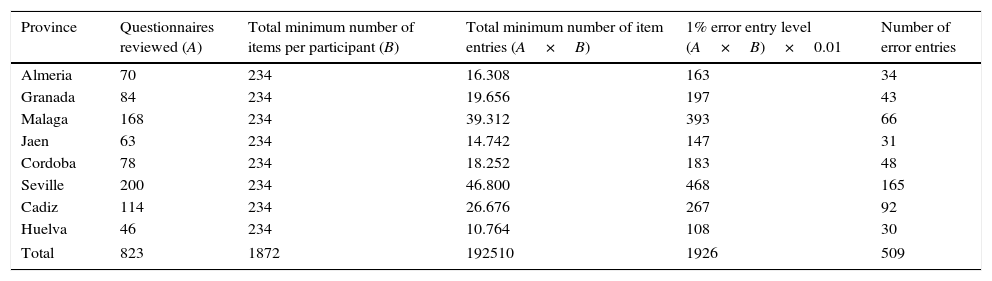

Table 3 shows error rates in data entry by province. The error rates of all the provinces were far below the 1% acceptability rate.

Error rates in data entry by province.

| Province | Questionnaires reviewed (A) | Total minimum number of items per participant (B) | Total minimum number of item entries (A×B) | 1% error entry level (A×B)×0.01 | Number of error entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almeria | 70 | 234 | 16.308 | 163 | 34 |

| Granada | 84 | 234 | 19.656 | 197 | 43 |

| Malaga | 168 | 234 | 39.312 | 393 | 66 |

| Jaen | 63 | 234 | 14.742 | 147 | 31 |

| Cordoba | 78 | 234 | 18.252 | 183 | 48 |

| Seville | 200 | 234 | 46.800 | 468 | 165 |

| Cadiz | 114 | 234 | 26.676 | 267 | 92 |

| Huelva | 46 | 234 | 10.764 | 108 | 30 |

| Total | 823 | 1872 | 192510 | 1926 | 509 |

The PISMA-ep initiative was carried out due to the need of Andalusian mental health authorities to obtain a realistic image of mental health disorders in the autonomous community and thus redefine mental health care policies within the regional healthcare system. Few community-based studies existed with current day diagnostic criteria for the assessment of prevalence and possible risk factors in Andalusia, the largest region in Spain. Although we expected results to be similar to those in other European populations, the culture and genetic mixture in the south of Spain could differ if compared with Northern European populations. It was therefore important to determine the levels of disability, correlations and prevalence of mental disorders. Furthermore, the study is innovative in its selection of several issues and results, with particular depth in having been applied in areas in which psychotic symptoms were identified and exhaustively explored within a general population and in a general mental health study.

General sample representationThe target sample number of participants and those who finally took part were almost the same (4518 compared with 4507). Proportions are shown in Table 1 and include age, gender, number of inhabitants of the province, urban status, marital status and education. This is practically a reflection of the cases reported in the most recent report by the Andalusian Institute of Statistics and Cartography of the whole Andalusian population.35 However, official unemployment rates are currently higher in Andalusia than those reported by the study participants, although this difference may be explained mainly by the undeclared jobs of people officially unemployed who possibly receive unemployment insurance, but have no formal employment contract.

Response ratesAlthough over two-thirds of the chosen homes originally had to be replaced by other equivalent ones selected at random (due to the lack of response or to the lack of suitability of the people living in the home), the overall response rate of those individuals who finally could be interviewed was fairly high (83.7%). It is as if the sample obtained was even more representative as a whole, higher than the average response rate of similar previous studies carried out in other places. It is quite plausible that Andalusian culture is favourable to collaboration in this type of study due to peoples’ well known approachability and kindness.

Data qualityThe supervision and monitoring of study data centred on ensuring that data reached a satisfactorily high level of quality. This was achieved homogeneously in the different provinces where there were well-trained coordinators. Although no reliability analysis was conducted, reliability increases with a common training programme and the sample size. These conditions formed part of the PISMA-ep study.

AssessmentsA wide range of assessments was included for the purpose of diagnosis and description. Apart from administering a general tool, such as the MINI, we tried to perform in-depth exploration of several clinical areas which other screening tools generally fail to take into account. To this end we added specific tools for obtaining psychotic symptoms (GPTS and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders), personality disorder (SAP and CEPER-III) and cognitive functioning (SCIP).

Main study limitationsThe limitations of this study mainly stem from its transversal design which hampers the establishment of any causal association between exposure and results. Another potential limitation may arise from the high number of homes which were replaced because the participants did not respond or because people were found not to be within the study's age range.

ConclusionsThe PISMA-ep study is a large transversal study with a sample which is representative of the autonomous community of Andalusia and gives a reliable picture of the prevalence of mental disorders and their correlatives. Its main strengths are the fairly high response rate and extensive level of exhaustive measures such as cognitive and personality assessments, together with a complete range of possible biological, psychological and social risk factors for mental disorders.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare they obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Cervilla JA, Ruiz I, Rodríguez-Barranco M, Rivera M, Ibáñez-Casas I, Molina E, et al. Protocolo y metodología del estudio epidemiológico de la salud mental en Andalucía: PISMA-ep. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2016;9:185–194.