We read the Letter to the Editor by Guija et al. on the valuation of post-traumatic psychiatric disease.1 We share their accurate opinions on the limitations of the current psychiatric chapter on for the valuation of the damages and prejudice causes to people by traffic accidents (commonly known as the “compensation scale” [CS]). The aim of this letter is to complement their input with our previous work in this field, and to comment on the project for the new CS which is planned to come into force on 1 January 2016.

In 2008 the Legal Medicine Institute of Catalonia published recommendations to facilitate, unify and adapt application of the CS; in the chapter on “Psychiatric Syndromes”2 we find the same difficulties that are pointed out by Guija et al.1: terminology that does not agree with diagnostic manuals, the lack of clear methodology for the estimation of each consequence and to evaluate its intensity, as well as ranges of scores that are unsuitable or insufficient. The solution we offered was, to summarise:

- -

Always refer to the current editions of diagnostic manuals to add to the reliability of the expert valuation.

- -

Use analogous valuations when this is necessary due to the small number of items included in the CS.

- -

When setting the score take into account the number and intensity of symptoms, the type of treatment and possible functional repercussions.

The Legal Medicine Institute of Catalonia subsequently issued specific recommendations on post-traumatic stress disorder or adaptive disorders.3,4 On the other hand, the valuation of psychiatric after-effects is always topical within the field of forensic medicine.5,6

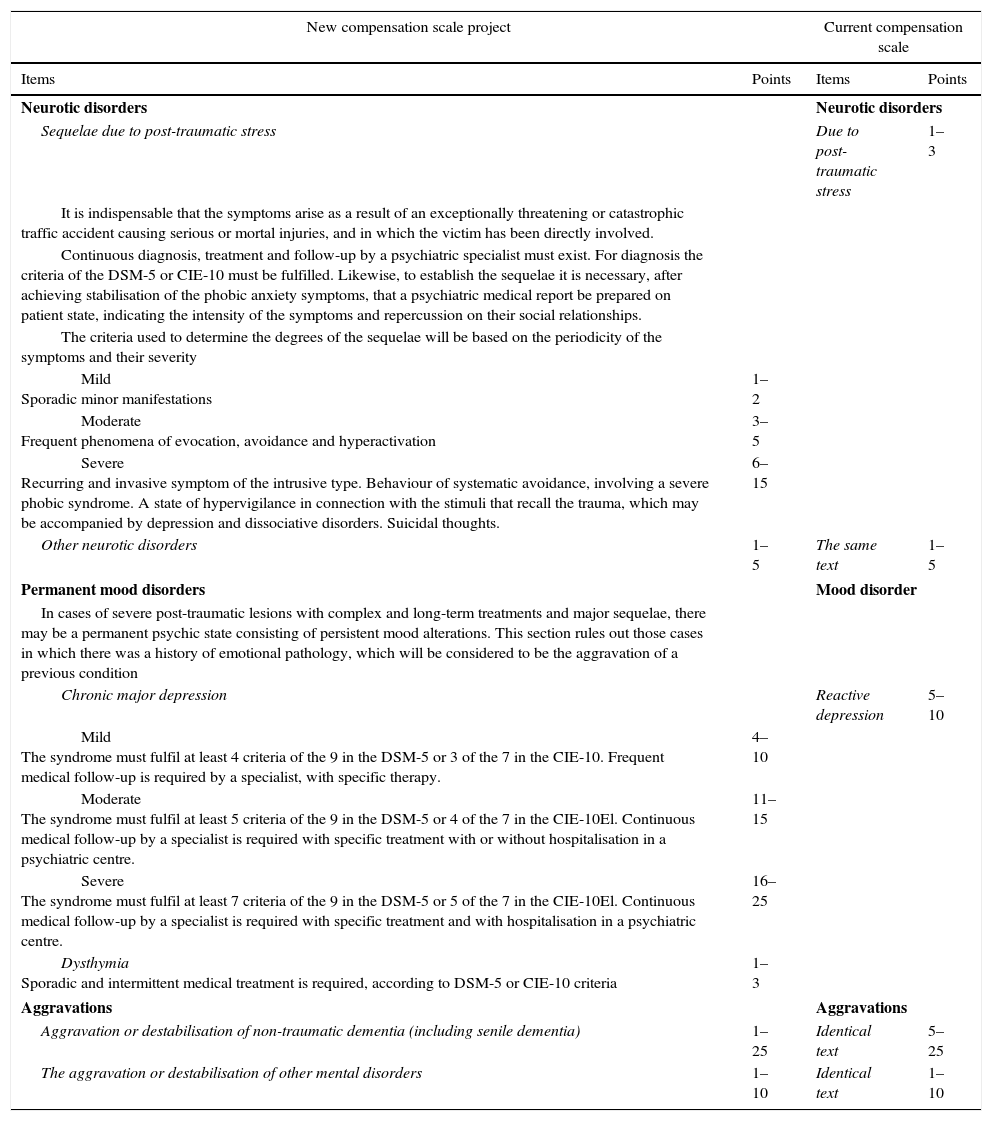

The Government recently passed the Projected Law on Reform of the CS,7 in which the table of sequelae includes a chapter on the nervous system divided into 2 parts of unequal length denominated “Neurology” and “Psychiatry”. The first of these covers motor and sensory sequelae in somewhat more than 7 pages, together with cognitive disorders and neuropsychological harm. The part on “Psychiatry”, in turn, takes up somewhat less than one page and includes items that already exist in the current CS, with some modifications (Table 1). We believe that the most outstanding new features are:

- -

Score ranges are considerably broadened for sequelae of post-traumatic stress (currently 1–3 points; planned: 1–15) as well as for permanent mood disorders (PMD; currently 5–10 points; planned: 4–25), although the criteria for application of the same are restricted. Moreover, the mere existence of emotional precedents without any other specification makes it obligatory to consider PMD as aggravations.

- -

Explicit criteria are introduced to establish the severity of sequelae deriving from post-traumatic stress and PMD, and for the latter this will depend on the number of DSM-5 or CIE-10 criteria fulfilled by the victim. However, in the above-mentioned restrictive tendency psychiatric hospital admission seems to be necessary for application of the upper range of the PMD score (16–25 points).

- -

Post-concussion syndrome and organic personality disorder, which are classified under “Psychiatric Syndromes” in the current CS, are now included under the new heading of “Neurology”. Organic personality disorder is combined under a single heading with frontal syndrome and alteration of the integrated higher brain function. All of this should not hinder the proper psychopathological evaluation of victims with craneoencephalic trauma.8

- -

As is the case for other serious sequelae, there is an additional condition of need for help by a third person in cases of major severe chronic depression and in the aggravation or destabilisation of non-traumatic dementia (table 2.C.2 of the new CS project). Nevertheless, there is no provision for compensation for future psychiatric care (table 2.C.1 of the new CS project).

| New compensation scale project | Current compensation scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Points | Items | Points |

| Neurotic disorders | Neurotic disorders | ||

| Sequelae due to post-traumatic stress | Due to post-traumatic stress | 1–3 | |

| It is indispensable that the symptoms arise as a result of an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic traffic accident causing serious or mortal injuries, and in which the victim has been directly involved. | |||

| Continuous diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by a psychiatric specialist must exist. For diagnosis the criteria of the DSM-5 or CIE-10 must be fulfilled. Likewise, to establish the sequelae it is necessary, after achieving stabilisation of the phobic anxiety symptoms, that a psychiatric medical report be prepared on patient state, indicating the intensity of the symptoms and repercussion on their social relationships. | |||

| The criteria used to determine the degrees of the sequelae will be based on the periodicity of the symptoms and their severity | |||

| Mild Sporadic minor manifestations | 1–2 | ||

| Moderate Frequent phenomena of evocation, avoidance and hyperactivation | 3–5 | ||

| Severe Recurring and invasive symptom of the intrusive type. Behaviour of systematic avoidance, involving a severe phobic syndrome. A state of hypervigilance in connection with the stimuli that recall the trauma, which may be accompanied by depression and dissociative disorders. Suicidal thoughts. | 6–15 | ||

| Other neurotic disorders | 1–5 | The same text | 1–5 |

| Permanent mood disorders | Mood disorder | ||

| In cases of severe post-traumatic lesions with complex and long-term treatments and major sequelae, there may be a permanent psychic state consisting of persistent mood alterations. This section rules out those cases in which there was a history of emotional pathology, which will be considered to be the aggravation of a previous condition | |||

| Chronic major depression | Reactive depression | 5–10 | |

| Mild The syndrome must fulfil at least 4 criteria of the 9 in the DSM-5 or 3 of the 7 in the CIE-10. Frequent medical follow-up is required by a specialist, with specific therapy. | 4–10 | ||

| Moderate The syndrome must fulfil at least 5 criteria of the 9 in the DSM-5 or 4 of the 7 in the CIE-10El. Continuous medical follow-up by a specialist is required with specific treatment with or without hospitalisation in a psychiatric centre. | 11–15 | ||

| Severe The syndrome must fulfil at least 7 criteria of the 9 in the DSM-5 or 5 of the 7 in the CIE-10El. Continuous medical follow-up by a specialist is required with specific treatment and with hospitalisation in a psychiatric centre. | 16–25 | ||

| Dysthymia Sporadic and intermittent medical treatment is required, according to DSM-5 or CIE-10 criteria | 1–3 | ||

| Aggravations | Aggravations | ||

| Aggravation or destabilisation of non-traumatic dementia (including senile dementia) | 1–25 | Identical text | 5–25 |

| The aggravation or destabilisation of other mental disorders | 1–10 | Identical text | 1–10 |

Thus definitively interesting changes are made, while a desire to restrict the consideration of psychiatric sequelae in the most severe cases is also perceptible, even though amendments with the purpose of modifying this last aspect have been presented.9 To conclude, we believe that the relationship between traffic accidents and mental health problems10 means that the psychiatric section of the CS will often have to be used for expert evaluations, so that recommendations such as those by de Guija et al.1 or those of our group2–4 will still be useful to ensure that it is used in the best possible way.

Please cite this article as: Xifró A, Bertomeu A, Idiáquez I, Puig L. La psiquiatría y el nuevo baremo de tráfico. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2016;9:231–233.