Validating brief-versions of mental health evaluation tools poses new challenges in terms of the process of their preparation and gaining evidence of validity. Brief-versions are important allies in professional practice when resources and the time required to evaluate by means of a complete test are limited,1 because they eliminate redundant items and reduce the fatigue, frustration and boredom of repeatedly answering very similar questions.2 In this regard, we consider the study undertaken by García-Portilla et al. to be valuable,3 because the evaluation of functional capacity using the UPSA brief-version opens up possibilities of its inclusion in the evaluation of intervention programmes. However, we believe that important methodological aspects were omitted in obtaining evidence of validity, which would call into question the calculations made taking the scores of the brief-version into account and the authors’ conclusions.

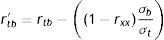

In the study, in order to obtain evidence of construct validity, the full version of the UPSA was correlated with its brief version (Sp-UPSA and Sp-UPSA-Brief, respectively), which is coherent since a high correlation between them is expected as the same construct is being quantified, but the Sp-UPSA-Brief has items in common with Sp-UPSA which spuriously increase the correlation. In order to mitigate this effect, there is a procedure which enables a correction to be made by correlated errors in order to achieve a more accurate estimate of such an association.4,5 This procedure is reflected in the following mathematical expression:

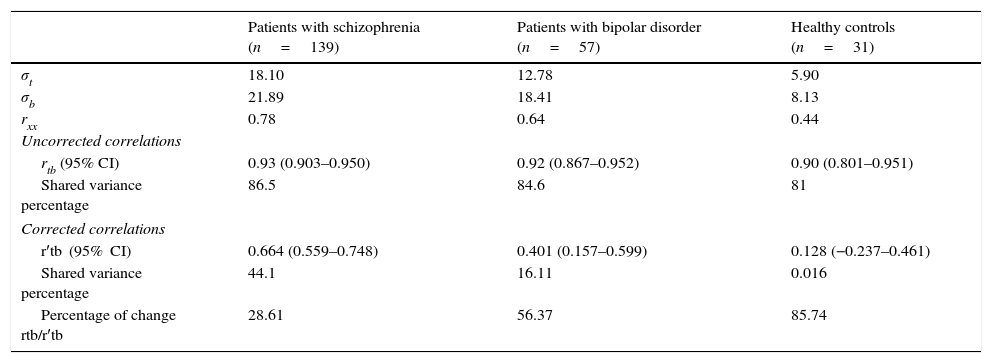

where r′tb is the corrected correlation between the full and the brief version; rtb, the original correlation between the full and brief version; rxx, the internal consistency reliability of the brief version; σb, the standard deviation (SD) of the brief version; and σt the SD of the full version. However, the SD of the total score of the full version is not given in the manuscript, and this is necessary for this procedure. For this reason, the mean and the SD of the total score was calculated using the data reported in the validation of the full version by García-Portilla et al.,6 which was possible because they used the same sample for both studies. To be specific, a total mean was considered (summing the means of each subscale separately) and a total SD was calculated from the coefficients of variation of 18.10; 12.78 and 5.90 for the groups Patients with schizophrenia, and Patients with bipolar disorder and Health controls, respectively. The results for the 3 groups are summarised in Table 1.Correlation between the full and the brief version of the Sp-UPSA.

| Patients with schizophrenia (n=139) | Patients with bipolar disorder (n=57) | Healthy controls (n=31) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| σt | 18.10 | 12.78 | 5.90 |

| σb | 21.89 | 18.41 | 8.13 |

| rxx | 0.78 | 0.64 | 0.44 |

| Uncorrected correlations | |||

| rtb (95% CI) | 0.93 (0.903–0.950) | 0.92 (0.867–0.952) | 0.90 (0.801–0.951) |

| Shared variance percentage | 86.5 | 84.6 | 81 |

| Corrected correlations | |||

| r′tb (95% CI) | 0.664 (0.559–0.748) | 0.401 (0.157–0.599) | 0.128 (−0.237–0.461) |

| Shared variance percentage | 44.1 | 16.11 | 0.016 |

| Percentage of change rtb/r′tb | 28.61 | 56.37 | 85.74 |

The findings indicate that on correcting the initial correlations for spuriousness, the statistics would need to be reinterpreted and the conclusions amended, because changes occurred in the magnitude of the correlations and in the statistical significance, added to which the percentage of change observed in the correlations was high. It is worth mentioning that the coefficients of reliability α are below the minimum accepted as adequate (>0.70),7 which could have affected the calculations considering the amount of measurement error existing in their scores.

For all of the above, the results with regard to the construct validity of the Sp-UPSA-Brief reported by García-Portilla et al. are questionable due to the lack of empirical equivalence between the full version and the brief version, in addition to the high measurement error presented by their scores.8 Added to this is the fact that both versions of the Sp-UPSA are principally used in the clinical environment and therefore can be considered “high risk tests” because they provide measurements with important direct consequences for those being examined, the programmes and the institutions involved in the evaluation.9 Similarly, the use of the instrument is questionable, even for research purposes.

Finally, it is clear that the impact of the common items should be mitigated when the equivalence between the brief and the full versions of an evaluation instrument is investigated, and thus the first step taken towards validating a brief instrument before correlations with other relevant criteria, and the instrument used to give robust conclusions regarding the construct evaluated.

Please cite this article as: Dominguez Lara S, Merino Soto C, Navarro Loli JS. Re-análisis de la validez de constructo de la escala breve para la evaluación de la capacidad funcional (Sp-UPSA-Brief) de García-Portilla et al. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2016;9:127–128.