Psychological pain is understood as an intolerable and disturbing mental state characterized by an internal experience of negative emotions. This study was aimed at making a Spanish adaptation of the Psychache Scale by Holden and colleagues in a sample of young adults.

Material and methodsThe scale evaluates psychological pain as a subjective experience. It is composed of 13 items with a Likert-type response format. Following the guidelines of the International Tests Commission for the adaptation of the test, we obtained a version conceptually and linguistically equivalent to the original scale. Through an online questionnaire, participants completed the psychological pain scale along with other scales to measure depression (BDI-II), hopelessness (Beck’s scale of hopelessness) and suicide risk (Plutchik suicide risk scale). The participants were 234 people (94 men, 137 women and three people who identified as a different sex) from 18 to 35 years old.

ResultsThe EFA showed a one-factor solution, and the FCA revealed adequate indexes of adjustment to the unifactorial model. It also showed good reliability of the test scores. The evidence of validity of the scale in relation to the other variables showed high, positive and statistically significant correlations with depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation and suicidal risk.

ConclusionIn summary, this Spanish adaptation of the Psychache Scale could contribute to improving the evaluation of both the patient with suicide risk and the effectiveness of psychological therapy, as well as suicidal behaviour prevention and intervention.

El dolor psicológico es entendido como un estado mental intolerable y perturbador caracterizado por una experiencia interna de emociones negativas. El presente estudio tiene como objetivo realizar una adaptación al contexto español de la escala de dolor psicológico de Holden y colaboradores en adultos jóvenes.

Material y métodosLa escala evalúa el dolor psicológico como experiencia subjetiva. Está compuesta por 13 ítems con un formato de respuesta tipo Likert. Siguiendo las directrices de la International Tests Commission para la adaptación de test, obtuvimos una versión equivalente conceptual y lingüísticamente a la escala original. A través de un cuestionario online, los participantes completaron la escala de dolor psicológico junto a otras escalas para medir depresión (BDI-II), desesperanza (escala de desesperanza de Beck) y riesgo suicida (escala de riesgo suicida de Plutchik). Los participantes fueron 234 personas (94 hombres, 137 mujeres y tres personas de otro sexo) de 18 a 35 años.

ResultadosEl AFE mostró una solución de un factor y el AFC reveló adecuados índices de ajuste del modelo unifactorial. También mostró una buena fiabilidad de las puntuaciones del test, y evidencias favorables de validez de la escala en relación con la depresión, desesperanza, ideación suicida y riesgo suicida (correlaciones altas, positivas y estadísticamente significativas).

ConclusiónLa adaptación al español de la escala de dolor psicológico puede contribuir a mejorar la evaluación tanto del paciente con riesgo suicida como la eficacia de la terapia psicológica, así como la prevención e intervención del comportamiento suicida.

Suicidal behaviour is associated with ideations, communications and behaviours that are potentially linked with the will to terminate one’s own life.1 These behaviours may differ in the form they take depending on their result, the importance of the act, the degree of intentionality and awareness of the results of the said behaviour.2 The public health impact of self-harming behaviour is not restricted to successful suicide, as suicidal ideation and attempted suicide are more habitual forms of behaviour, and they often occur prior to death by suicide.3

The phenomenon of suicide is currently a global health problem which causes almost one million deaths per year. It is estimated that annual deaths due to suicide in the next decade will amount to one and a half million individuals.4 The suicide rate in Spain in 2017 was 7.91 per 100,000 inhabitants,5 or 3,679 suicides. In spite of investment in research and the implementation of preventive programmes which focus on mitigating suicidal behaviour in our society, this effort has not led to a reduction in the number of suicides.6 Mortality due to suicide has in fact remained stable in our country over the last 10 years, and it has even undergone a marked increase in the case of women.7 Far from being a problem which exclusively affects adults, the prevalence of suicidal behaviour is especially high among adolescents and young adults. Suicide is the second cause of premature death in individuals aged from 15 to 29 years old.4 Likewise, 4% of Spanish adolescents have attempted suicide and 6.9% suffer suicidal ideation.3 Suicidal ideation in adolescents has been associated with the consumption of psychotropic substances, the presence of depressive symptoms, problematic usage of Internet and conflicts with peers in the educational context.8 In the same way, attempted suicides and suicidal ideation in young people have also been associated with reduced emotional well-being and a low level of satisfaction with life.3

Suicidal behaviour is a multifactorial phenomenon which arises due to a combination of different types of variables and temporal influence, and it is especially difficult to predict9,10 In spite of this, there is sufficient theoretical and empirical evidence to support the central role played by psychological pain in the prediction of suicidal behaviour.11

Psychological pain,12 which is also referred to in the literature as mental, psychic pain or internal disturbance, includes the beliefs, thoughts, emotions and behaviours which form part of the experience of pain of this type.13 Meerwijk and Weiss14 reviewed the descriptions of psychological pain used of the last 60 years, finding the following common characteristics: an unpleasant feeling (which is often experienced as a disintegration of the self), negative evaluation and self- incapacity or deficiency (in comparison with evaluation of the current state compared to the one that is desired), a long-lasting state which takes time to resolve, one that is hard to maintain over time without severe consequences. Although this concept is not new in scientific literature, it acquires relevance in the study of suicide through the work of Shneidman.15–17

For Shneidman,15 psychological pain refers to an intolerable and disturbing mental state which is characterised by the internal experience of negative emotions (such as shame, anxiety, guilt, humiliation, solitude and fear). Shneidman16 states that the shared stimulus for suicide is unbearable psychological pain, understanding suicide as the means of achieving cessation of the awareness of unbearable pain. This statement, which was subsequently simplified in the axiom without pain there is no suicide,18 places psychological pain at the core of other current models of suicidal behaviour (such as the 3 step theory19).

The theoretical consensus on the relevance of psychological pain as a key factor in some of the principle theories on suicide is supported by many items of empirical evidence.20,21 Intolerable levels of psychological pain have been associated with a higher risk of suicide22,23 and are also a risk factor for individuals with and without a mental health diagnosis.11,24

The degrees to which authors delimit the concept of psychological pain and describe the behaviours associated with it have given rise to clearly differentiated measuring instruments. For example, these include the Psychache Scale,25The Orbach and Mikulincer Mental Pain Scale26 or The Mee-Bunney Psychological Pain Assessment Scale.27 All of these scales contribute to the quantification of psychological pain, and they have appropriate psychometric properties.

Due to its ease of administration and capacity to predict self-harming behaviour, the Psychache Scale25 is one of the most widely used instruments. This is a self-administered one-dimensional scale based on Shneidman’s definition of psychological pain.15 This scale has good psychometric properties25,28,29 and it has been adapted to the cultural contexts of different non-English speaking countries (e.g., in Portuguese30, Polish or Chinese32). This scale successfully differentiates between individuals who have attempted suicide and those who have not,25 and it predicts suicidal ideation and attempted suicide better than depression and desperation.33,34

The purposes of this study are to adapt the Psychache Scale25 instrument for measuring psychological pain to the Spanish context and analyse its psychometric properties (reliability and validity). To this end, firstly the phases of adaptation which most often give rise to error will be taken into account. These phases consist of contextualization, construction and adaptation, application and the interpretation of scores. The aim is to obtain an agreed linguistically and conceptually equivalent preliminary version of the original assessment instrument. Likewise, as part of the adaptation process the psychometric properties of the resulting scale will be analysed to obtain empirical data on how it works. More specifically, the evidence for its validity will be examined, based on its internal structure using exploratory and corroboratory factorial analysis, and the internal consistency of the scale will be calculated. Additionally, data showing its validity will be obtained, based on its relationship with other relevant variables for the prediction of self-harming behaviour, such as depression, desperation and the risk of suicide.

The expectation is that the test scores will be found to be reliable, with a single factor scale structure that agrees with previous findings.25,31 In the same way, given the results of previous studies22,23,33,35,36 high level positive correlations are expected between psychological pain, depression and desperation. Lastly, and given that psychological pain is thought to be the common stimulus for suicide16 and a central element within the formation of suicidal ideation,19 a high level of positive correlation is also expected to be found between psychological pain, suicidal ideation and the risk of suicide.

Material and methodsSubjectsThe sample was selected using convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria were an age from 18 to 35 years and voluntarily accepting to take part in the study. Fifty-five cases were eliminated from the total number of those who agreed to take part in this research (n = 289), as they did not fulfil the age inclusion criterion or because data were lacking respecting the study variables. The final sample was composed of 137 women, 94 men and 3 individuals who defined themselves as belonging to another sex (n = 234); all of them live in Spain, and their average age was 25.69 years (SD = 3.51). Their other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | Av = 25.69 (SD = 3.51) |

| Sex | |

| Woman | 137 (58.5%) |

| Man | 94 (40.2%) |

| Other | 3 (1.3%) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary | 5 (2.1%) |

| Secondary | 77 (32.9%) |

| University | 152 (65%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 193 (82.5%) |

| Married/living together/stable partner | 41 (17.6%) |

| Divorced | 0 (0%) |

| Widow(er) | 0 (0%) |

| Occupation | |

| Student | 97 (41.5%) |

| Housework | 3 (1.3%) |

| Unemployed | 21 (9%) |

| In work | 113 (48.3%) |

| Children | |

| No | 226 (96.6%) |

| Yes | 8 (3.4%) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 60 (25.6%) |

| Muslim | 4 (1.7%) |

| Agnostic | 46 (19.7%) |

| Atheist | 82 (35%) |

| Indifferent | 39 (16.7%) |

| Suicidal ideation | |

| No suicidal ideation | 176 (75.2%) |

| Passive suicidal ideation | 54 (23.1%) |

| Active suicidal ideation | 4 (1.7%) |

| Diagnoses mental illness | |

| Anxiety | 4 (1.71%) |

| Depression | 4 (1.71%) |

| Attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity | 2 (.85%) |

| Mixed anxiety-depressive disorder | 2 (.85%) |

| Insomnia | 1 (.43%) |

| Compulsive obsessive disorder | 1 (.43%) |

The process of adapting the psychological pain scale to the Spanish context was undertaken following the guidelines of the International Tests Comission37 for adaptation and translating tests. These instructions centre on 4 phases: the context, construction and adaptation, application and the interpretation of scores.

The first phase involving the context included consideration of whether the construct to be measured (psychological pain) can be extrapolated to the target culture of the adaptation.38 The research group discussed the conceptual equivalence of the construct and the need to distinguish between psychological pain and physical pain in the expression. Review of the different adaptations of the original measuring instrument added to the conclusion that the psychological pain construct may be acceptably extrapolated to the Spanish context.25 The good results obtained in cultural contexts other than Canada (where the instrument was first developed), such as China,32 Poland31 or Portugal,30 warranted the suitability of adapting the scale to Spanish. This was most especially the case for the adaptation carried out in Portugal (due to its proximity, cultural similarity and similar suicide rate to that in our country).

In the following phase of constructing and adapting the measuring instrument the aim was to translate the items from English into Spanish independently, before checking the equivalence between the original items and their Spanish translations. An interdisciplinary team was formed for this purpose, composed of an official translator and 2 bilingual psychologists (a psychometry expert and an expert in self-harming behaviour). A group of experts then discussed the conceptual and linguistic equivalence of the 3 translations, with the aim of selecting the items which obtained the highest level of agreement, and to deal with the resulting discrepancies. After some minor linguistic changes a Spanish version was obtained thanks to the agreement of the experts. An online pilot study was then conducted in the general population to detect the degree to which the items were comprehended. It was confirmed that the subjects understood them appropriately.

As is the case for the original test, the Spanish adaptation of the Psychache Scale is designed to be self-administered. It was therefore thought necessary to include the distinction between psychological pain and physical pain in the statement, together with the advisability of doing the test in a comfortable environment and the estimated time it would take. Finally, like the original version, the total score of the scale varies from 13 to 65 points, depending on the total of the numerical values for each reply option. Higher scores correspond to more unbearable perceptions of psychological pain.

A complete questionnaire was administered through social networks and other online platforms for this study. It was composed of the adapted scale, the variables used to obtain evidence of validity, and certain relevant sociodemographic questions such as age, sex, educational level and marital status). All of the respondents were informed that the test is voluntary, with the purpose of the study and the mechanisms which guarantee their anonymity and confidentiality. They were also given a contact in case they felt any doubts about the questionnaire. All of the respondents signed an informed consent form prior to taking the questionnaire. This study was approved by the Human Research Bioethics Committee of Almeria University.

InstrumentsAdaptation of the Psychache Scale into Spanish (hereinafter PS-E; the original scale in English25). A self-administered scale based on Shneidman’s definition of psychological pain.16 It includes 13 items with 5 options for a Likert-type response. From item 1 to item 9 the response options run from “never” to “always”, and from item 10 to item 13 the response options vary from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Higher scores correspond to more intense and frequent (more unbearable) perceptions of psychological pain.

The risk of suicide was measured using the adaptation into Spanish39 of Plutchik’s risk of suicide scale.40 This self-administered scale consists of 15 items which evaluate previous attempts at suicide, the intensity of current ideation, feelings of depression and desperation and other aspects associated with the attempt. Its score runs from 0 to 15 points, where higher scores indicate a greater risk of suicide. The Spanish version proposes a cut-off point at 6, and has an estimated reliability of 0.90 using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and of 0.89 in the test-retest. In our study the scale had a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80 and a split-half coefficient of 0.83 using the Spearman-Brown formula.

The severity of depressive symptoms was measured using the Spanish adaptation41 of version ii of Beck’s depression inventory, (BDI-II).42 The BDI-II includes 21 multiple response items, with options running from 0 to 3 points. The maximum total score is 63 points. The cut-off point above which potential clinically relevant depression is considered is 18 points. In our study, the instrument displayed a high level of internal consistency, with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.94 and a split-half coefficient of 0.95 using the Spearman-Brown formula.

Suicidal ideation will be measured by item 9 of the adaptation into Spanish41 of version ii of Beck’s depression inventory.42 Item 9 (0 = I have no thought of killing myself; 1 = I have thought of killing myself, but would not do so; 2 = I would want to kill myself; 3 = I would kill myself if I had the opportunity) evaluates the existence of suicidal ideation, distinguishing between passive (1) and active forms (2 and 3).

Desperation was measured using the Spanish version43 of Beck’s desperation scale.44 This self-administered scale contains 20 items associated with an individual’s negative expectations for their future, their well-being and their ability to cope with difficulties in their life. The response format is true or false, depending on whether an item reflects the actual situation of the respondent or not. The total score varies from 0 to 20 points. This scale has displayed good psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 and a cut-off point at 9 over 20.42 Cronbach’s alpha in our study is .87, and the split-half coefficient using Spearman-Brown’s formula is .87.

Data analysisPrior to data analysis atypical cases were studied based on the anomaly index (atypical cases are defined as those with anomaly indexes containing more than 2.5 typical deviations) in the study variables. No case was eliminated because it was atypical.

The descriptive statistics were calculated first (the average, standard deviation, asymmetry and kurtosis) corresponding to the items in the PS-E scale. Univariate normalcy was then checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. This test showed a statistically significant result (P < .001), so that the univariate normalcy null hypothesis was rejected together with multivariate normalcy.

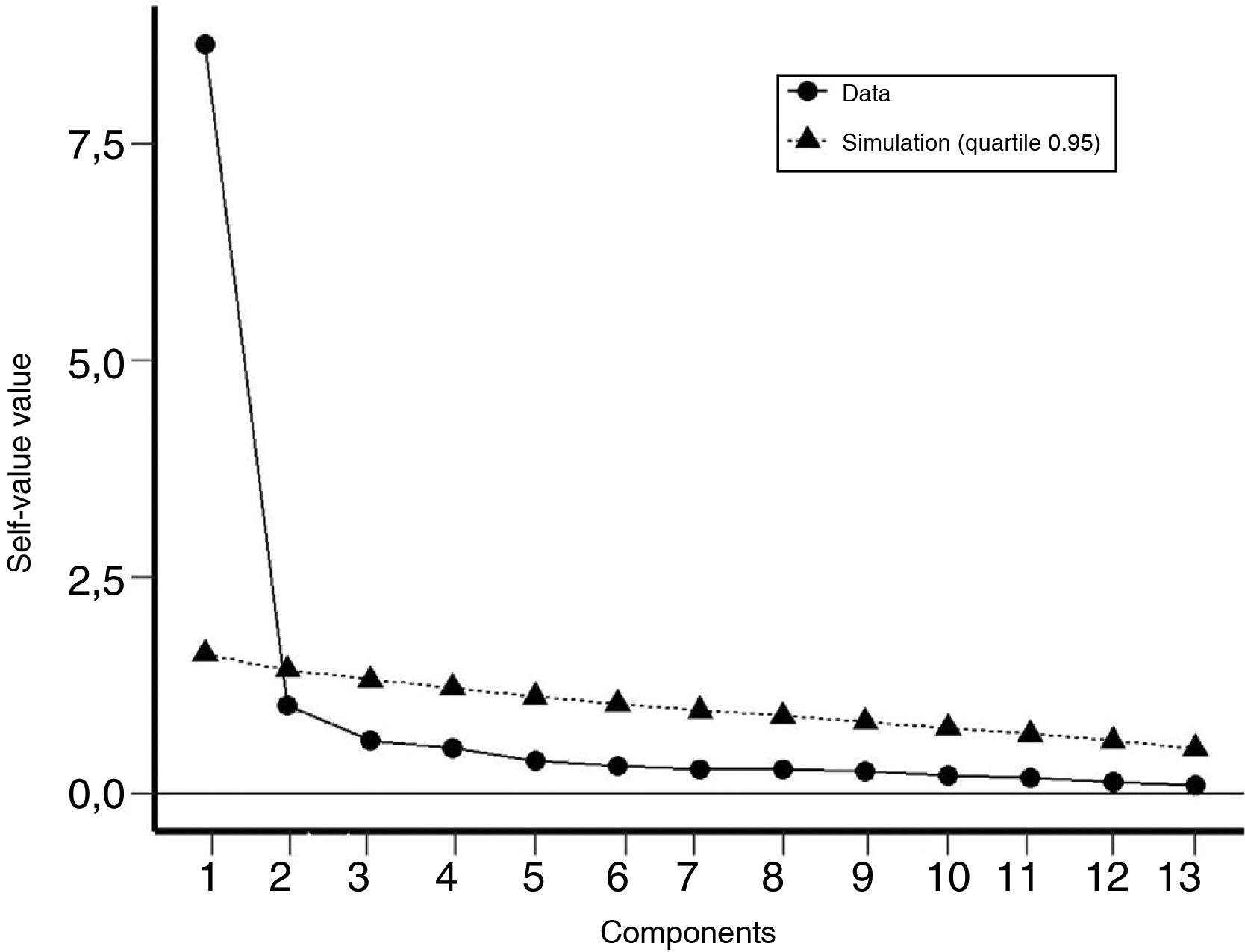

Befire performing the factorial analyses we randomly divided the total sample (n = 234) into 2 subsamples. Subsample 1 (n = 117) was used for exploratory factorial analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index was obtained together with Bartlett’s sphericity test to measure the appropriateness of the correlation matrix for factorial analysis. The calculation method using main axes was selected, as it was not possible to assume multivariate normalcy. The number of factors to be extracted was determined by parallel analysis using a single factor solution, in agreement with the original test.

This single factor solution was analysed using confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) with the data obtained in subsample 2 (n = 117). The unweighted least squares criterion was applied due to the small size of the sample, incompliance with the supposition of multivariate normalcy and the ordinal Likert-type format used.45 The adjustment measures reported according to this methods are: the average square root of the residual values (RMR), adjusted goodness of fit (AGFI) and the normalised fit index (NFI). The adjustment indexes are interpreted with the cut-off points proposed by Hu and Bentler.46 Approximately values of >.90 for AGFI, >.95 for NFI and <.05/.06 for RMR indicate good fit of the model.

Subsequently, the data of the total sample were used to calculate the reliability of the PS-E scores using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, the Spearman-Brown split-half procedure and the Omega coefficient. Lastly, to explore the evidence for validity based on the relationship with other variables, correlation analysis was performed in the whole sample between the total score of the PS-E and the BDI-II, item 9 of the BDI-II, Plutchik’s risk of suicide scale and Beck’s desperation scale. The selection of both random samples, the descriptive analyses, correlations and exploratory factorial analysis were carried out using version 25 of SPSS software. Version 22 of AMOS was used for confirmatory factorial analysis and version 0.9.1 of JASP was used to calculate the Omega coefficient and parallel analysis.

ResultsDescriptive statistics of the Psychache ScaleTable 2 shows the descriptive statistics of the scale for the whole sample of participants. The range of response options runs from 1 to 5. Item 1 (I feel psychological pain) obtained the highest average score (Av = 2.41; SD = 1.09). The lowest average score corresponded to items 10 (I cannot bear my pain more; Av = 1.57; SD = 0.96) and 11 (because of my pain, my situation is unbearable; Av = 1.57; SD = 1.01). The average total score of the PS-E was 25.19 (SD = 11.91). The range of total score ran from 13 (minimum) to 65 (maximum).

Descriptive statistics, exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) and the standardized solution of confirmatory factorial analysis (CFA) of the items in the PS-E scale.

| N | Items | Av | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | EFA (N1 = 117) | CFA (N2 = 117) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I feel psychological pain | 2.41 | 1.09 | .35 | –0.60 | .73 | .80 |

| 2 | I feel internal pain | 2.12 | 1.06 | .63 | –0.46 | .78 | .82 |

| 3 | My psychological pain seems worse than any other physical pain | 2.29 | 1.29 | .66 | –0.62 | .79 | .78 |

| 4 | My psychological pain make me want to shout | 1.95 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.10 | .68 | .67 |

| 5 | My pain makes my life dark | 1.89 | 1.14 | 1.17 | 0.47 | .86 | .87 |

| 6 | I do not understand why I suffer | 1.99 | 1.13 | .99 | 0.12 | .69 | .52 |

| 7 | Psychologically I feel awful | 2.03 | 1.15 | 1.10 | 0.13 | .85 | .88 |

| 8 | I am in pain because I feel empty | 2.03 | 1.27 | .98 | –0.25 | .87 | .79 |

| 9 | My soul is in pain | 1.84 | 1.15 | 1.26 | 0.63 | .79 | .82 |

| 10 | I cannot bear my pain any more | 1.57 | 0.96 | 1.82 | 2.81 | .83 | .86 |

| 11 | My situation is unbearable because of my pain | 1.57 | 1.01 | 1.83 | 2.52 | .81 | .81 |

| 12 | My pain is shattering me | 1.64 | 1.06 | 1.68 | 1.93 | .87 | .87 |

| 13 | My psychological pain affects everything I do | 1.87 | 1.20 | 1.18 | 0.16 | .81 | .85 |

| Explained variance | 63.83% | AGFI = .992 | |||||

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin | .941 | NFI = .993 | |||||

| Bartlett’s sphericity | 1.369.36* | RMR = .059 |

Reliability and evidence for validity based on its internal structure: exploratory and confirmatory factorial analysis.

An EFA was performed with the responses to subsample 1 for the items in the PS-E scale. The values obtained in the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test (KMO = .941) and Bartlett’s sphericity test (Chi-squared = 1369.36; gl = 78; P < .001) were compatible with the factorization of the correlations matrix. The parallel analysis was concordant with the extraction of a single factor (Fig. 1), and this single factor solution explained 63.83% of the variance. All of the items in the PS-E scale saturated in a single factor of psychological pain above .68 (Table 2). In the same way, to check whether all of the items saturated in a factor of general psychological pain, a CFA was performed with the data corresponding to subsample 2. The values of the standardized factorial loadings of the PS-E items ranged from .52 to .88 (Table 2), in agreement with the solution shown by the EFA. The values of the fit indexes obtained (AGFI = .992, NFI = .993 and RMR = .059) showed a good fit for the single factor model.

The reliability of the PS-E scale scores for the whole sample was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient at 0.96. A similar result was obtained using the Spearman-Brown formula and the split-half procedure (.95), as well as the result of applying the Omega coefficient (.96).

Evidence of validity based on the association with other variablesEvidence for the validity of the whole sample was obtained based on the relationship between the total PS-E score and 4 external variables which are closely linked to suicidal behaviour: the severity of depressive symptoms (BDI-II), desperation (Beck’s desperation scale), suicidal ideation (item 9 of the BDI-II) and the risk of suicide (Plutchik’s suicide risk scale). All of the associations found were positive and moderate to high as well as statistically significant (Table 3) in agreement with our hypothesis.

Pearson correlation coefficients between the total scores of the PS-E scale and the other variables.

This study adapted one of the most important psychological pain measuring instruments, the Psychache Scale,25 to the Spanish context. Firstly, and using the guidelines of the International Tests Comission37 for the adaptation of tests, an agreed conceptual and linguistic equivalent version of the original scale was obtained. The adaptation was completed by analysing the psychometric properties of the resulting Spanish version. The findings are congruent with the original version and with the results obtained with adaptations to other cultural contexts.30,31

In terms of its internal structure, the results of this work are consistent with the solution of a single factor, and they also agree with those obtained with the Polish version31 and with the conceptualization of psychological pain which forms the basis of the original scale.15,25 Nevertheless, several authors have found a 2 factor solution in the English version:28,47 one factor which includes the first 9 items, and a second factor with the 4 remaining items. Both studies28,47 agree in pointing out that these factors do not have an interpretation which is based on the content of the items, as they result from an artefact caused by the change of response format in the last 4 items. It is therefore recommended to use the total score corresponding to the sum of all of the items in the scale. Moreover, and consistently with previous findings, the score of the PS-E show a good level of reliability which is similar to the original version of the scale,25 as well as the Portuguese30 and Polish versions.31

Respecting the evidence for validity based on associations with other variables, and similarly to the results found in previous studies,22,23,33,35,36 this work shows correlations that are high, positive and statistically significant between psychological pain, depression and desperation. The results are consistent with the hypothesis of the existence of a general common negative factor,48 composed in this case of psychological pain, desperation and depression. However, to clarify the relationship between these constructs, Troister and Holden36 analysed the factorial differentiation between a measurement of psychological pain, depression and desperation. They concluded that in spite of the existence of a certain degree of overlap between the operationalization of the 3 constructs, sufficient factorial differentiation exists, as well as the unique input from each construct for the prediction of suicidal behaviour. On the other hand, psychological pain correlates moderately, positively and significantly with suicidal ideation and the risk of suicide. These findings are consistent with the results of studies that analysed the predictive capacity of psychological pain in connection with suicidal behaviour and in comparison with desperation and depression.34,36,49,50 These results also agree with the theories that attempt to explain and predict self-harming behaviour using psychological pain as the key element (e. g., the 3 step theory19 and the suicide theory15).

The limitations of this study include its relatively small sample. Additionally, convenience sampling, incompliance with the inclusion criterion in connection with age and the incomplete data led to the elimination of cases. This in turn gave rise to a slight over-representation of female participants. As a result the results of this study should be considered with caution when generalizing them to the young adult population of Spain. Likewise, due to the clinical nature of these variables and the low level of suicidal behaviour in the general population, the range of the data is restricted to a certain degree. In spite of these limitations, this study centres on cultural adaptation in a young adult population as the preliminary phase before using the scale in a clinical context. Future studies with a longitudinal design will make it possible to analyse the contribution of psychological pain and other relevant factors. They will also evaluate psychological pain in other populations (e. g., the clinical population at high risk of suicide), adding evidence on the generalisation of the findings and the predictive validity of psychological pain.

ConclusionsTo summarise, the Psychache Scale25 is one of the most widely used and easy to administrate psychological pain measuring instruments. The availability of a psychological pain measurement instrument adapted to the Spanish context will contribute to improving the evaluation of the risk of suicide in patients, while also guiding psychological therapy and evaluating its efficacy. This measure may also be used to evaluate symptoms in clinical trials of drugs. Patients with depression often mention feeling substantial relief in their psychological pain following treatment with antidepressant drugs.51 On the other hand, traditional research into the risk factors for self-harming behaviour (such as mental illness) has been shown to have a low degree of specificity and little predictive value, so that the scientific approach to the phenomenon of suicide requires further development.52,53 Psychological pain is a key element in models that explain suicide, with a notable level of empirical evidence regarding its predictive capacity for suicidal behaviour.15,19 The PS-E therefore makes it possible to replicate these models in the general and clinical Spanish populations, as well as making significant scientific contributions that will affect the prevention of suicidal behaviour and intervene in the same.

FinancingThis work was financed by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport for the Education of University Teachers (State Programme for the Promotion of Talent and Employability), awarded in public competition (Ref. FPU16/00534).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.