Patients with cardiovascular pathology may undergo an anxiety state related to their disease. It has been demonstrated that after an acute coronary syndrome 30% of patients experience high anxiety levels, and that half of them will remain under this condition one year after.1 According to Spielberger,2 there are two kinds of anxieties: state anxiety (AS) and trait anxiety (AT). AS reflects a transitory emotional condition characterized by subjective and consciously perceived feelings of tension and apprehension, which may vary in intensity. In contrast, AT refers to a general tendency to respond with anxiety to perceived threats and is a relatively stable characteristic.

Little is known about the relation between anxiety, its different types and aortic disorders. We sought to evaluate anxiety levels in this setting and whether these are related exclusively to a trait or not. During six months we conducted a prospective inclusion of patients with thoracic aorta disease undergoing follow-up in a single outpatient Cardiology. Evaluation of the anxiety as a trait (AT) or state (AS) was performed through the STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) questionnaire. Each form has 20 items using four-point Likert-scales, with total scale scores ranging from 20 to 80 and being directly proportional to the anxiety level.3 Progressive aortic disease was defined as an increase in any of the following conditions: aortic regurgitation grade, transaortic peak gradient, ascending aortic aneurysm (AAA) diameter and dissection or intramural haematoma size.

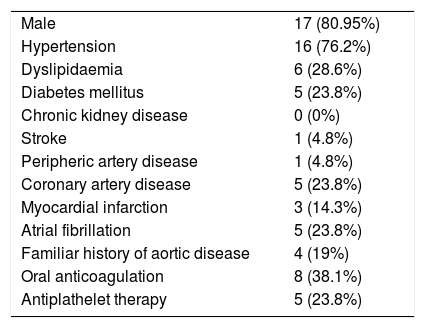

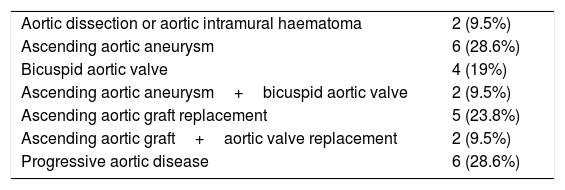

As a result, 21 patients were evaluated. Mean age was 65.4±13 years. Basal characteristics are shown in Table 1 and aortic pathologies evaluated in Table 2.

Basal characteristics.

| Male | 17 (80.95%) |

| Hypertension | 16 (76.2%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 6 (28.6%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (23.8%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0 (0%) |

| Stroke | 1 (4.8%) |

| Peripheric artery disease | 1 (4.8%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (23.8%) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (14.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (23.8%) |

| Familiar history of aortic disease | 4 (19%) |

| Oral anticoagulation | 8 (38.1%) |

| Antiplathelet therapy | 5 (23.8%) |

Aortic pathologies.

| Aortic dissection or aortic intramural haematoma | 2 (9.5%) |

| Ascending aortic aneurysm | 6 (28.6%) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 4 (19%) |

| Ascending aortic aneurysm+bicuspid aortic valve | 2 (9.5%) |

| Ascending aortic graft replacement | 5 (23.8%) |

| Ascending aortic graft+aortic valve replacement | 2 (9.5%) |

| Progressive aortic disease | 6 (28.6%) |

Global mean scores were 57.2±5.4 for AS and 56.1±6.3 for AT, with no significant difference between them (p=0.3). Patients diagnosed with AAA (58.6 vs 42.3, p=0.02) and bicuspid aortic valve (59.5 vs 53.3, p=0.05) showed significantly higher scores for AS, without differences in AT (57.7 vs 54.5, p=0.21 and 59 vs 56.2, p=0.3 respectively).

There was a trend towards a higher AS score in patients with progressive aortic disease compared with stable disease patients (60.2 vs 55.7, p=0.10), with no significant difference in AT (57.7 vs 56.2, p=0.4). All subjects obtained AS scores above the 90th centile compared with general population data.4 Patients with thoracic aortic disease present quantitative data of anxiety evaluated through a standardized questionnaire, specially those with bicuspid aortic valve and AAA. Anxiety as a state, probably related to their pathology, is predominant. These findings have been demonstrated previously in other cardiovascular settings.1 Although our study has the limitation of patients fulfilling the questionnaire the same day that they visit the outpatient clinic, we found fairly high scores which would be hardly explained exclusively to that fact. Even when not statistically significant, the greater anxiety manifested by patients with progressive aortic disease may reflect anticipative stress due to a probable future surgical intervention. From a therapeutic approach, rehabilitation programmes with and individualized approach (reminding “the person-centre care”) for patients with previous aortic surgery and therapies to avoid and control anxiety should be considered.5 Even, as previously suggested, the active search for biomarkers in anxiety states could be useful.6

Our study is still underway and whether these observations have any impact on hard clinical outcomes or not should be investigated with a great number of patients and with a long-term follow-up.