Alterations in the genes of lysine methylation as Lysine-specific demethylase 6B (KDM6B) have been associated with multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Until now, there are few cases in the literature attributed to KDM6B mutations. This gap may be due to the fact that the exome sequencing technique is still being implemented in routine clinical practice.

Material and methodsA case is presented with its clinical and phenotypic characteristics. The sequence exome analysis was done with the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ MedExome capture kit+mtDNA 47Mb. The psychopathological approach from mental health was carried out through individual and family interviews, the Conner's questionnaires, ADHD rating scale, as well as the psychometry.

ResultsA frameshift variant in the KDM6B gene related to neurodevelopmental disorders with facial and body dysmorphia was obtained. The case was oriented as a neurodevelopmental disorder secondary to a genetic alteration and a comorbid Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

ConclusionsThe clinical peculiarities shared by patients identified with the KDM6B mutation, raises the need to recognize it as a particular entity. The possibility of applying the exome sequencing technique to patients with syndromic phenotype and developmental impairment may clarify its etiopathogenesis. It is highly probable that the complexity of these cases requires an approach by a multidisciplinary team that includes genetics, neurology and psychiatry, among other specialties. The coordinated approach is essential to have a comprehensive vision of the case.

Las alteraciones en los genes de metilación de lisina como la desmetilasa 6B de lisina (KDM6B) se han asociado con múltiples trastornos del neurodesarrollo. Hasta ahora, existen pocos casos en la literatura atribuidos a mutaciones del gen KDM6B. Esta brecha puede deberse al hecho de que la técnica de secuenciación del exoma aún está en fase de implementación en la práctica clínica habitual.

Material y métodosSe presenta un caso con características clínicas y fenotípicas. El análisis de secuenciación exómica se realizó con el kit de captura Nimblegen SeqCap EZ MedExome + mtDNA 47Mb. La aproximación psicopatológica desde salud mental se realizó a través de entrevistas individuales, familiares, los cuestionarios Conners, ADHD rating scale, así como la psicometría.

ResultadosSe obtuvo una variante de cambio en el gen KDM6B que ha sido relacionado con trastornos del neurodesarrollo con dismorfias faciales y corporales. El caso fue orientado como un trastorno del neurodesarrollo secundario a una alteración genética, un trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH).

ConclusionesLas peculiaridades clínicas que comparten los pacientes identificados con la mutación KDM6B, plantea la necesidad de reconocerla como una entidad particular. La posibilidad de aplicar la técnica de secuenciación del exoma a pacientes con fenotipo sindrómico y retraso generalizado en el desarrollo puede aclarar su etiopatogenia. Es muy probable que la complejidad de estos casos requiera el abordaje de un equipo multidisciplinar que incluya genetistas, neurólogos y psiquiatras, entre otras especialidades. El enfoque coordinado es fundamental para obtener una visión integral del caso.

DNA mass sequencing techniques has made outstanding advances in recent years. Firstly, there was the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) in 2003.1 The first articles on exome sequencing were published in 2001 by the journals Nature and Science. This project started in 1990 with the aim of mapping all the genes of the human genome at a physical and functional level, as well as determining the sequence of chemical base pairs that make up human DNA. The technological advances over the years have reduced the cost of full DNA sequencing making possible the use of this technique in the routine clinical practice. This advance will offer the possibility of expanding the knowledge of genetic mutations responsible for syndromic entities that have not been affiliated to date.

Usually, our exome contains multiple changes that occur randomly and do not always have a clinical (epigenetic) impact. Therefore, it is necessary to discriminate which of the changes found in the exome would explain the phenotypic expression of the patient. To be able to discern which mutations may be responsible for the observed symptoms, it is necessary to study: the exome of the parents and the analysis of the functions of the genes where we find changes.

Having a genetic analysis as early as viable, that confirms the clinical diagnosis will allow us to approach the disease with much more information. Also, this may help with anticipating clinical presentations through early stimulation, preventive medication, or monitoring the patient according to the type of disease.

In the recent and relevant study published by Satterstron2 102 risk genes for Austism Spectrum Disorder were identified and the KDM6B was one of them.2 This is the largest exome sequencing study of ASD to date (n=35.584 individuals, including 11.986 with ASD). Their results highlight novel genetic, phenotypic and functional findings, and point out that most risk genes have roles in regulation of gene expression or neuronal communication.

Some neurodevelopmental disorders caused by alteration of the genes responsible for histone methylation have already been identified, such as Kabuki syndrome 1,3 Kabuki Syndrome 2,4 Kleefstra syndrome,5 Wiedermann-Steiner syndrome6 or Weaver syndrome.7

In the case presented, the alteration of the KDM6B, responsible for the demethylation of the trimethylated lysine 27 in histone H3, is related to dysmorphic facial features, delayed development, and intellectual disability. These changes, detected by exome sequencing, were subsequently classified as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) due to their novel nature and an unclear link between alterations in the KDM6B gene and neurodevelopmental delay. The methylation and demethylation of histone proteins at specific residues regulates gene expression during developmental.8

It is presumable that the genotypic and phenotypic findings in this patient, and those previously described by Stolerman,9 in which the KDM6B gene is involved, represents a specific neurodevelopmental disorder.

Material and methodsClinical history and phenotypic information were obtained from the patient's medical records. The patient's legal guardians gave their informed consent for the publication of this article. All procedures employed were reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional review committee.

Standard laboratory conditions were used for exome analysis with the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ MedExome capture kit+mtDNA 47Mb and with 90X coverage. The bioinformatics analysis was carried out following the best GATK practices and included the analysis of single nucleotide variants (SNV) and small insertions and deletions. The analysis of SNV and indels was carried out through the described pipeline by Laurie.10

Clinical caseA 6-year-old patient referred by the Center for Early Diagnosis and Attention (CDIAP) is presented in outpatient psychiatric clinic of the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology of the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital in Barcelona. The CDIAP are public centers, financed by Social Services, made up of multidisciplinary teams that attend to patients aged 0 to 5 years old. Among the professionals that make up this team are psychologists, physiotherapists, speech therapists, social workers, and child neurologists. These teams generally offer individualized attention to the cases attended.

In the case that we present, the patient was treated from 16 months until he was six years of age at the CDIAP due to delay in a psychomotor and speech areas. He received physical, occupational, and speech therapy weekly. The CDIAP clinical reports highlighted a delay in the acquisition of milestones in several areas: language, motor skills, and bowel and bladder continence. At the psychomotor level, it highlights a delay in psychomotor development with free walking at 24 months and sitting at 15 months; generalized hypotonia without loss of muscle strength, and little marked reflexes. He was capable of doing loads on his hands and feet, but he showed an avoidant attitude towards the task. On the other hand, there was a language delay: use of propositional language at 36 months and three-element sentences at 40 months. Furthermore, there was a delay in toilet training, achieving good bowel and bladder control during the day, and at night at around 36–40 months of age. Regarding the behavior, in frustrating situations, he consoled himself by compulsively sucking his fingers or the whole hand, and he displayed psychomotor restlessness with difficulty in maintaining sustained activities.

By the CDIAP's child neurologist criteria, he was referred to the Neurology Service where he received annual follow-ups for suspicion of an unknown genetic entity. In 2013, the initial genetic testing consisted of a karyotype, a chromosomal microarray, and Fragile X testing that was unremarkable. Regarding imaging testing, a brain MRI was performed, finding a slight craniofacial disproportion related to macrocephaly. In 2014 an audiometry was performed, detecting a mild hearing loss in the right ear with flat tympanometry.

Upon reaching the maximum age of care in this center, situated at six years of age, it is referred to the Child and Youth Mental Health Center (CSMIJ) for follow-up.

In the family history, we can highlight that the patient is the second pregnancy of a healthy non-consanguineous couple. He has a presumably healthy older sister. There is a 3rd-degree relative through the mother's line with a language delay. From his personal history: it was a well-controlled gestation with maternal diabetes during the pregnancy that started the first trimester. The diabetes was initially controlled with diet and later with insulin. It was a full-term gestation at 39+3 weeks. Weight at birth: 2950g. Size: 50cm. Cranial circumference: 33cm. Ultrasound checks were performed at the perinatal time without detecting complications.

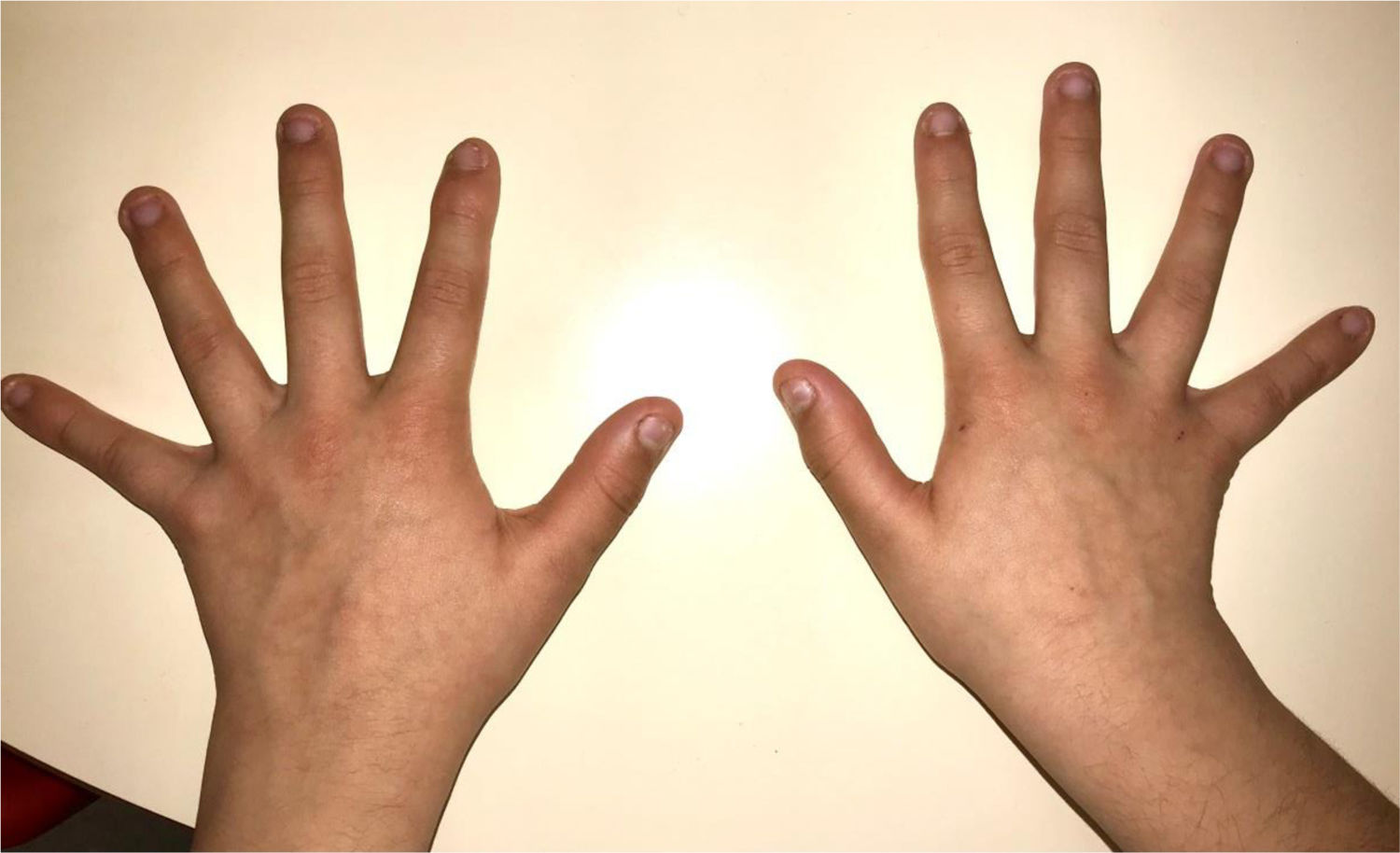

During the physical examination, we observed a squared shaped macrocephalic skull, double apical swirl, and frontal hair with significant lateral hair. He presented deep eyes, long and bushy eyelashes, synophrys eyebrows plump on the outside, and a small nose. Also, he had tonsil hypertrophy and a complete and closed palate. He presented a long hair area on the outside of both elbows and mild hypertrichosis in the upper dorsal elbow area and his hands and fingers appeared somewhat widened and thickened (see Table 1; Figs. 1–3 attached).

Clinical features.

| Neurodevelopment | Motor delaysLanguage delaysHypotonicAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| Facial features | MacrocephalyProminent foreheadCoarse featuresDouble apical swirlFrontal hairSynophrys eyeboesLong and bushy eyelashesSmall noseTonsil hypertrophy |

| Body features | Hypertrichosis in the upper dorsal elbow areaLittle marked reflexesHands and fingers widened and thickened |

The reason for consultation at the CSMIJ was to assess the possibility of pharmacological control of the hyperkinetic symptoms that were interfering with his usual activities, in the academic, social, and family settings. The patient is unable to stay seated, moving continuously, jumping, and singing at inappropriate times or places. This hyperkinetic behavior prevents him from following the classes correctly and disturbs his classmates, causing them to reject him. On the other hand, frequent episodes of dysregulation behavioral appear with tantrums in situations of frustration, not expected nor appropriate to his chronological age. In the assessment by the psychiatry service, it was decided to administer the Conner's questionnaires parents’ version and teachers’ version, the ADHD rating scale questionnaire, and a psychometric assessment through the WISC-IV (see Table 2).

Questionnaires used for the evaluation of the case.

| Test | Results |

|---|---|

| Conners Test | Parents’ questionnaire: meets criteria for attention deficit T74, perfectionism T77, psychosomatic T88, Hyperactivity/impulsivity T80. |

| Teachers’ questionnaire: meets criteria for attention deficit. Cognitive problems/attention deficit T70 | |

| ADHD rating scale | Attention deficit: 15 (Pt90), Hyperactivity/impulsivity 18 (Pt 93). Total: 33 |

| WISC-IV | Verbal comprehension: 78 (Similarities T 7, Vocabulary T 6, Information T5), Perceptual Reasoning: 89 (Block Design T 7, Concepts T 10, Matrix reasoning T 8), Working Memory: 61 (Digit span T 3, Arithmetic T 4), Processing Speed: 68 (Coding T 2, symbol search T 6).Full Scale IQ: not valuable; GII: 80 |

WISC-IV: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV; IQ: Intelligence Quotient; GII: General Intelligence Index.

After the initial assessment and evaluating all the data of the case, it was oriented as a Neurodevelopmental delay, generalized hypotonia, and ADHD secondary to the underlying disorder. The phenotypic peculiarities of the patient in the physical examination added to the psychological symptoms made the professionals treating him suspect that there was a genetic mutation that had not been identified in 2013. With all that, the function of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Department was to focus on the possibility of improving the capacity for behavioral self-regulation, reducing hyperkinesia and impulsivity while seeking to increase the time of sustained attention.

The patient was prescribed with intermediate-release psychostimulants (methylphenidate up to 1.07mg/kg per day). The proposed treatment managed to reduce the core symptoms of ADHD, improving his integration among the class group as well as improving his ability to do the academic work. No adverse side effects have been evidenced to date. So, it has been possible to maintain the treatment over years, adjusting according to weight. Over time, there was an improvement in the global functionality of the patient.

With the possibility of applying the massive exome sequencing technique in July 2019, the patient's exome was sequenced and analyzed using massive sequencing techniques. A frameshift variant classified as probably pathogenic was obtained in the KDM6B gene. Low population frequency variants (<0.01) of pathogenicity were also reviewed via computer simulation for genes related to the patient's phenotype, without detecting other significant findings.

There are few cases registered in the literature where the KMD6 mutation is directly related as responsible for a neurodevelopmental disorder. To date, there are 12 patients with a KDM6B mutation (c.2598delC:p.SerArgfsTer27) who present neurodevelopmental delay and dysmorphia described in the scientific literature.9 After this finding, a genetic study was carried out in the parents. In line with the results previously obtained, the study of segregation of that genetic change in both parents confirmed that it was a de novo mutation. Given these results, it was not considered necessary to carry out the study on the healthy brother.

In the same sense as the cohort presented by Stolerman,9 the described patient here presents similar characteristics of dysmorphia and neurodevelopmental alterations, being a de novo change respect to their parents. It is considered that the genetic change in KDM6B could be responsible for the clinical manifestations observed in this patient. Patients to date identified with this mutation have been collected using the website Gene Matcher through international collaboration.11

LimitationsThere are two main limitations to this article. The first one is due to the massive exome sequencing technique. This technique has high specificity and sensitivity for the determination of single nucleotide variants and indels of up to 10 nucleotides. By cons, other types of genetic variants such as repeated expansions, structural variants or variants in regions of high homology may not be detected. So, the technology for capturing and mapping the exome has its limitations and only 90% of the exome is evaluable.

The other remarkable limitation is precisely that a single case is described, with its phenotype and psychopathological expression, along with the exome alteration detected. Even so, its scientific dissemination is remarkable due to its recognized etiopathogenic explanation. Knowledge of these rare cases but with defined characteristics can facilitate clinical practice in terms of their understanding and possible needs.

DiscussionUsually, in the case of rare genetic diseases with a complex clinical manifestation, the diagnosis by exome sequencing was carried out at the end of a long process that involves multiple tests that are sometimes invasive. In this scenario, multidisciplinary intervention becomes crucial to achieve a comprehensive and non-fragmented view of the patient, which includes an understanding of the psychiatric clinical expression as an epigenetic expression.

With the presentation of this case, we example that the sequencing of exomes of children in whom we suspect a monogenic condition is highly effective at a clinical and economic level, especially when it is carried out early in the diagnostic process. When presented with a patient that has rare phenotypic features that seem unrelated to the psychiatric clinical presentation, we should include an undelaying genetic syndrome as part of the differential diagnosis.

In conclusion, as others authors declare the early referral of children with the suspicion of undiagnosed syndromes to clinical genetics professionals should be considered.12

Conflict of interestThe authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.