There is evidence of the relevance of fear, anxiety and avoidance of activity in the maintenance of pain in fibromyalgia. Recently, an opposite pattern based on the persistence in activity has been described. To date, the cognitions that impede modifying this pattern are unknown. Therefore, the aim of this study is to reach consensus on the content of an instrument that assesses those cognitions.

Material and methodsA Delphi method was applied to reach consensus on the content of the Clinic Scale of Persistence in Activity in Fibromyalgia (CCAP-FM).

ResultsAfter three rounds of consultation, an acceptable consensus was reached. Those items that received an average rating of relevance lower than 5/10 and that at least the 75% of experts recommended removing were excluded. The preliminary questionnaire of persistence in activity was composed of 30 items.

ConclusionsThe consensus on the content of the CCAP-FM will allow advancing towards the assessment of the relation between the modification of the cognitions responsible for the maintenance of the persistence in activity and the clinical improvement in people with fibromyalgia.

Existen sólidas pruebas de la relevancia del miedo, la ansiedad y la evitación de la actividad en el mantenimiento del dolor en la fibromialgia. Recientemente se ha descrito un modelo opuesto basado en la persistencia en la actividad. Actualmente desconocemos las cogniciones que dificultan la modificación de este patrón de comportamiento. Por consiguiente, el objetivo del estudio es la definición consensuada del contenido de un instrumento que las evalúa.

Material y métodosMediante consulta prospectiva a expertos se consensuó el contenido del Cuestionario Clínic de Persistencia en la Actividad en la Fibromialgia (CCAP-FM).

ResultadosTras 3 rondas de consulta se alcanzó un acuerdo aceptable. Se excluyeron los ítems que obtuvieron una valoración media consensuada de relevancia inferior a 5/10 y que al menos el 75% de los expertos recomendó eliminar. El cuestionario preliminar de persistencia en la actividad quedó compuesto por 30 ítems.

ConclusionesLa definición del contenido del CCAP-FM permitirá iniciar el proceso de evaluación de la relación entre la modificación de las cogniciones responsables del mantenimiento de la persistencia en la actividad y la mejoría clínica de las personas con fibromialgia.

Fibromyalgia is a disorder characterised by generalised pain and a low pain threshold detected in at least 11 of the 18 predefined areas where tendons join (tender points).1 Even though its aetiology is unknown, there are tests suggesting that the somatic symptomatology observed in fibromyalgia is related to central sensitisation of the nociceptive system.2,3 Nociceptive system sensitisation is a protecting mechanism activated after potentially harmful peripheral stimulation either because of its repetition or intensity. This stimulation reduces the pain threshold and amplifies nerve conduction of subsequent peripheral stimulation, whether potentially harmful (hyperalgesia) or benign (allodynia). In the absence of a permanent lesion or repetitive peripheral stimulation, central nociceptive system sensitisation is resistant but reversible.4 One of the factors that may maintain central nociceptive system sensitisation is sustained peripheral stimulation.4 One of the factors potentially responsible for sustained peripheral stimulation is strenuous activity. In animal research, strenuous activity has been observed to increase generalised, but not peripheral, hyperalgesia, an effect that is gender dependent.5

In people with fibromyalgia, a behaviour pattern of brief alternating periods of strenuous activity followed by prolonged periods of inactivity has been observed.6–8 The same pattern has been observed in other pain disorders9 and in chronic fatigue syndrome.10,11 Modifying this pattern seems to reduce the intensity of the pain symptoms.12,13

People with fibromyalgia are conscious of the negative effect that this behaviour pattern has on the intensity of their pain symptoms and relapses. Furthermore, their environment usually shows a negative attitude towards this type of behaviour.6 However, this behaviour pattern is resistant to change.

Two models have been described that attempt to explain this contradiction: first of all, the model based on the “Ergomania” concept14 maintains that hyperactivity is produced as overcompensation for unconscious dependency needs, body narcissism, masochism and excessive perfectionism. To date, it has not been possible to operationalise some of these constructs in order to submit them to experimental research. Secondly, the “avoidance-resistance” model15 argues that maintaining strenuous activity obeys a maladapted attentional coping pattern, consisting of minimising pain. To date, this model has only gotten empirical support for clinical pain in a lower back pain study.

From the beginning, multidisciplinary treatment programmes for fibromyalgia have included modifying the strenuous activity pattern, based on the balance between activity and pain (pacing). However, the definition of the concept of pacing continues to be controversial. It was initially defined by its function (adapting activity level to avoid increasing pain, ultimately reducing association between activity and pain and facilitating the progressive achievement of functional objectives); however, it has recently been defined only by behaviours that include slowing activity execution, taking breaks, maintaining a moderate pace or dividing activities into manageable portions, independently of the objective of those behaviours.16 This merely descriptive definition may bring about problems when assessing the therapeutic effect of this strategy, since some patients may use it as an avoidance strategy while others may apply it, with a progressive increase in activity, to improve their functional capacity.17 Measuring pacing and its relationship with clinical variables, such as functional incapacity, is not without its own problems as well. One of the instruments most used in assessing this behaviour pattern includes 6 items that explain a moderate but significant percentage for variance in functional disability.16 However, at least 2 of these 6 items presuppose, in the way that they are written, greater physical capacity to be a result of applying pacing strategies. Consequently, a third of the scale may suffer from redundant measurement. Furthermore, these 2 items are those which least saturate the 1-dimensional pacing factor, defined by the analysis of 4 questionnaires about pain coping strategies.18 Finally, the results regarding the relationship between functional incapacity and pacing are still contradictory, observing both a beneficial effect and lack of effect, or even a harmful effect, in adopting pacing strategies.17,18

Consequently, we currently do not know the content of the beliefs that prevent people with fibromyalgia from modifying the pattern of activity persistence despite their increasing pain. Not knowing these beliefs limits the effectiveness of therapeutic strategies that attempt to modify the pattern (it is subjectively more cost-effective to maintain the persistence pattern rather than face the assumed negative consequences of modifying it). This lack of knowledge also makes applying restructuring techniques specifically more difficult (involving more evaluation sessions oriented towards guided discovery). Likewise, the impossibility of accurately measuring these beliefs impedes the assessment of their correlation with the evolution of pain symptoms in fibromyalgia, as well as other variables, such as perfectionism. As a result, the objective of our study was to find a consensus regarding the content of a thought inventory for measuring the beliefs potentially responsible for maintaining the pattern of activity persistence in fibromyalgia.

Materials and methodsGenerating the items for the clinical questionnaire for activity persistence in fibromyalgiaGiven that there are no historical data with respect to the thoughts responsible for maintaining the pattern for activity persistence, a sample of statements was collected that reflected the beliefs responsible for maintaining activity despite increasing pain in fibromyalgia patients. This first subgroup of statements was extracted ad hoc from a qualitative analysis of clinical interviews involving guided discovery. Statements were also collected retrospectively from cognitive records that were part of treatment for fibromyalgia patients in the Multidisciplinary Unit at Barcelona Clinical Hospital. The thoughts, reported by patients as responsible for maintaining the pattern of persisting in activity, were rewritten by a panel of experts to adapt them to an item format, being as concise as possible and avoiding ambiguities, colloquial language or professional jargon. In an effort to prevent response tendencies (for example, excessive acquiescence), inverse content items were also included. Comprehensibility of the final set of 57 items was verified by a group of 40 patients.

Participants: Panel of expertsTo arrive at a consensus in the preliminary selection of the most relevant items, a general prospective method was used, based on the consultation of experts (Delphi method). The Delphi method allows a consensus to be reached among experts through anonymous consultations in successive rounds, avoiding the “leadership” effect and maintaining maximum autonomy on the part of the experts.

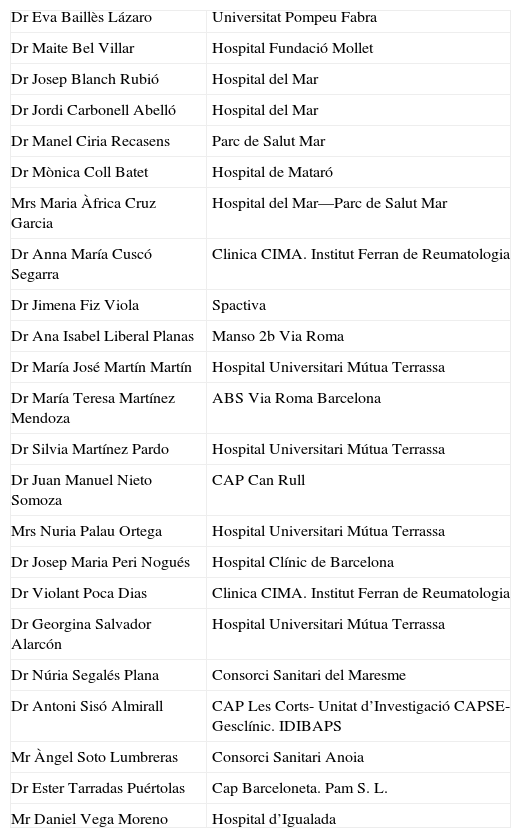

The panel was selected with the objective of representing, as broadly as possible, both health specialists that typically care for people with fibromyalgia and the different levels of care at which these patients are treated. Furthermore, we wanted to avoid the presence of bias due to coinciding job specialities and environments. A specialist was considered to be a candidate for participating in the study if he or she had clinical or research experience with fibromyalgia. The panel of experts were recruited using an introductory letter about the position, which included the study objective and the research process. Participants were excluded if they could not be located after 3 attempts to contact them or if they refused to participate in the study. The final panel was composed of an interdisciplinary group of specialists in clinical psychology, family medicine and rheumatology, all from primary and hospital care (Annex 1).

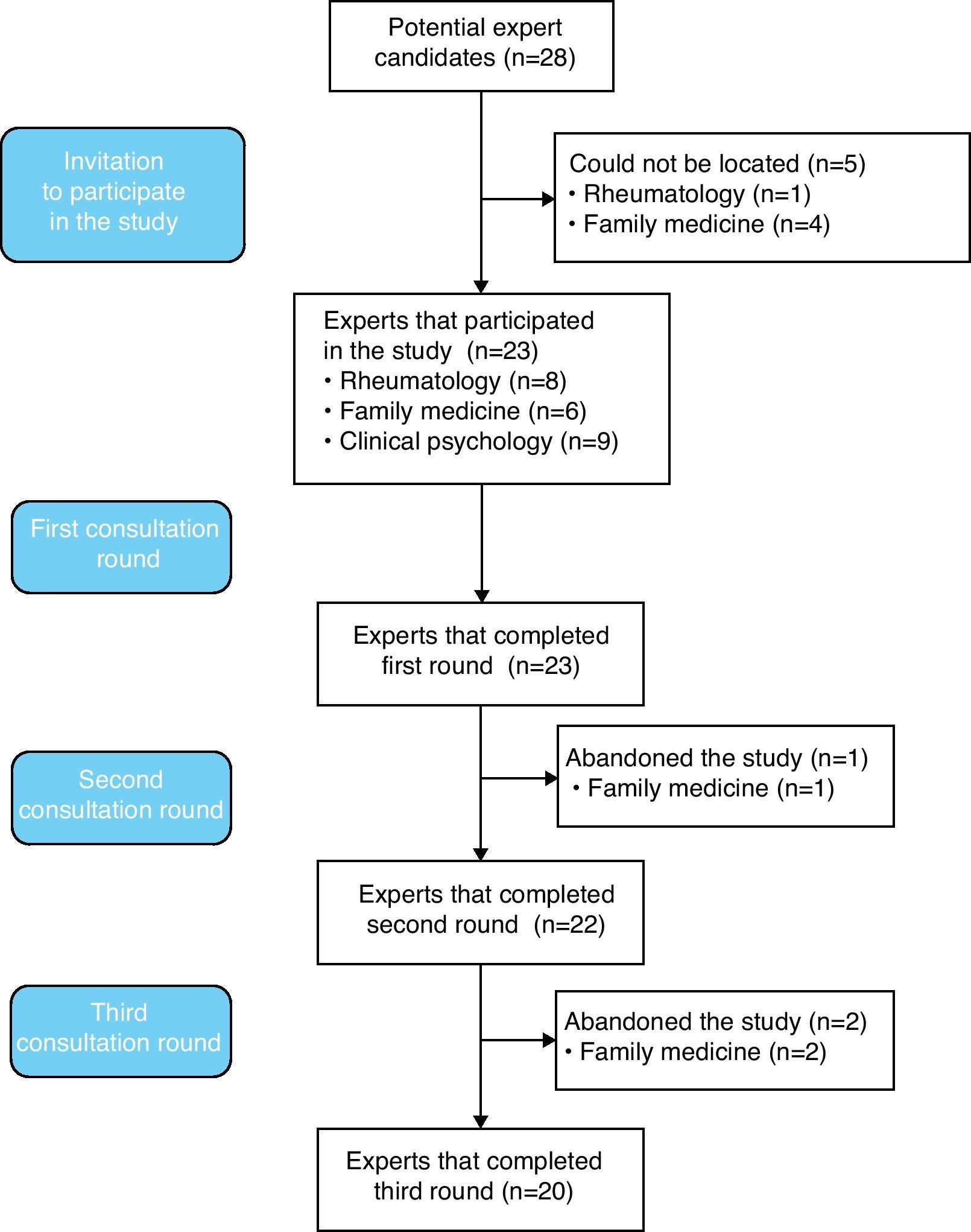

Consensual selection of the most relevant itemsThree rounds of online consultation were conducted at 1-month intervals, with reinforcement 15 days after each mailing, using forms constructed ad hoc. In the first mailing, the experts were asked to assess each of the items from the original sample on a scale of 0 (irrelevant) to 10 (essential). With the data obtained, interquartile range was calculated, as were central tendency and dispersion measures. In the second mailing, the mean relevance assessment for each item was indicated and a re-evaluation was requested for each, using the same scale format as before. The experts were offered the possibility of defending their opinions when their assessment differed from the group mean. In the third and last mailing, the mean relevance for each item from the previous round was given, along with the grouped justifications of the discrepancies observed in the previous round, and a final decision was requested with respect to maintaining or eliminating the items. Consequently, a mean consensus on the relevance of each item was finally reached. Furthermore, the dispersion of opinions (final interquartile intervals) was obtained and the dichotomous decision of maintaining/rejecting each item was made. An item was excluded if at least 75% of the experts recommended eliminating it or if it had a mean relevance assessment of less than 5 after consensus. Fig. 1 shows each of the steps and the expert flow during the consultation process.

The Clinical Research Ethics Committee at Barcelona Clinical Hospital approved the study.

Statistical analysisTo verify the presence of bias in the panel of experts—due to predominance of men or women, health specialties or care levels—a chi-squared test was used.

The quartiles, central tendency and dispersion measurements were calculated for each item according to the experts’ assessments in the first 2 consultation rounds. To verify the stability between the first and second assessments carried out by the panel and, thus, the potential need for a third round, the reduction in interquartile range was verified and a parametric comparison of means test was applied for the means of the independent groups (t-test). To verify the degree of agreement among the experts, the Spearman rho coefficient and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated.

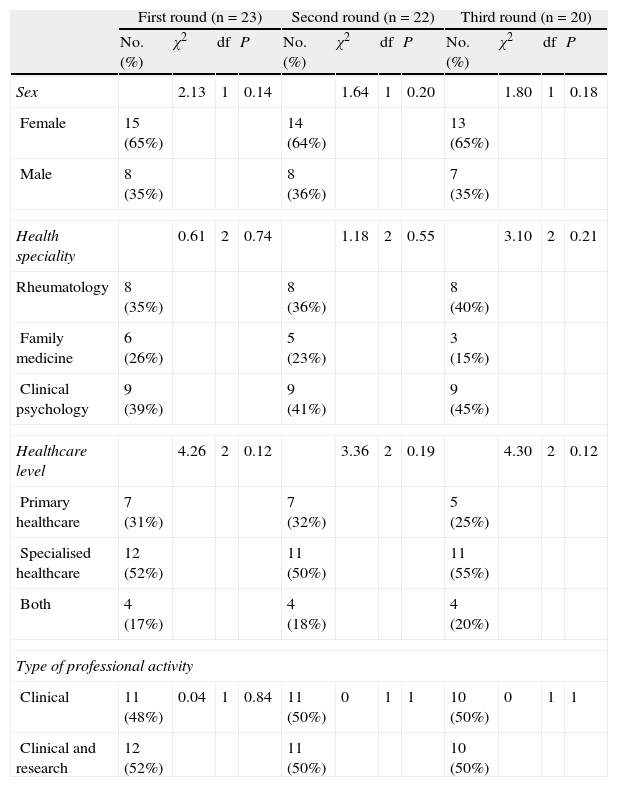

ResultsAfter being invited to participate in the study, 23 of the 28 experts agreed to be part of the panel and began the consultation rounds. No statistically significant predominance was observed for sex, health speciality, care level or type of activity in any of the consultation rounds (Table 1).

Expert panel composition in each of the consultation rounds.

| First round (n=23) | Second round (n=22) | Third round (n=20) | ||||||||||

| No. (%) | χ2 | df | P | No. (%) | χ2 | df | P | No. (%) | χ2 | df | P | |

| Sex | 2.13 | 1 | 0.14 | 1.64 | 1 | 0.20 | 1.80 | 1 | 0.18 | |||

| Female | 15 (65%) | 14 (64%) | 13 (65%) | |||||||||

| Male | 8 (35%) | 8 (36%) | 7 (35%) | |||||||||

| Health speciality | 0.61 | 2 | 0.74 | 1.18 | 2 | 0.55 | 3.10 | 2 | 0.21 | |||

| Rheumatology | 8 (35%) | 8 (36%) | 8 (40%) | |||||||||

| Family medicine | 6 (26%) | 5 (23%) | 3 (15%) | |||||||||

| Clinical psychology | 9 (39%) | 9 (41%) | 9 (45%) | |||||||||

| Healthcare level | 4.26 | 2 | 0.12 | 3.36 | 2 | 0.19 | 4.30 | 2 | 0.12 | |||

| Primary healthcare | 7 (31%) | 7 (32%) | 5 (25%) | |||||||||

| Specialised healthcare | 12 (52%) | 11 (50%) | 11 (55%) | |||||||||

| Both | 4 (17%) | 4 (18%) | 4 (20%) | |||||||||

| Type of professional activity | ||||||||||||

| Clinical | 11 (48%) | 0.04 | 1 | 0.84 | 11 (50%) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 (50%) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Clinical and research | 12 (52%) | 11 (50%) | 10 (50%) | |||||||||

All experts completed the first consultation round.

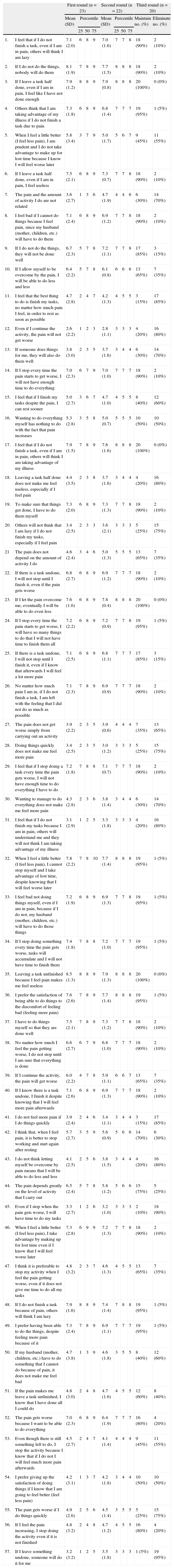

Of the 57 items, 23 (40.4%) were considered very relevant (median consensual relevance in the top quartile), 11 (19.3%) were considered moderately relevant (median consensual relevance in the third quartile), 19 (33.3%) were considered of little relevance (median consensual relevance in the second quartile) and 4 (7%) were considered irrelevant (median consensual relevance in the first quartile).

Round 2Of the 23 experts who began the study, 22 (96%) finished the second consultation round.

Of the 57 items, 8 (14%) were considered very relevant, 25 (43.9%) were considered moderately relevant and 24 (42.1%) were considered of little relevance. No significant differences were observed in the mean relevance assessment values between the first and second consultation round (less agreement observed: items no. 7 [t=−1.8; P=.08] and no. 52 [t=1.8; P=.08]). Spearman's rho correlation coefficient showed statistically significant correlations between all of the experts’ assessments, with the exception of 4 experts who disagreed with each other and 1 expert who disagreed with the rest of the panel. Nonetheless, a very acceptable general degree of agreement was found (ICC=0.97; P<.01). The interquartile range between the relevance assessments from the experts was considerably reduced in all items. Sufficient consensus was thus reached, deeming the third consultation round unnecessary and allowing us to proceed to the final decision round regarding maintaining/eliminating the items.

Round 3A total of 20 (87%) experts completed the third consultation round.

Three quarters of the panel deemed that 30 (53%) of the items should be maintained (a 100% consensus was reached in 4 items) and 11 (19%) should be eliminated. In 16 of the items, less than 75% of the panel reached a consensus, so no final decision was considered.

Table 2 summarises the relevance quartiles, mean assessments and dispersion of opinions in the first and second consultation rounds, as well as recommendations regarding maintaining or eliminating each of the items.

Relevance quartiles, assessment means and dispersion of opinions in the first and second consultation rounds, and final consensual decision regarding maintaining or eliminating each of the items.

| First round (n=23) | Second round (n=22) | Third round (n=20) | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | Percentile | Mean (SD) | Percentile | Maintain no. (%) | Eliminate no. (%) | ||||||

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 25 | 50 | 75 | ||||||

| 1. | I feel that if I do not finish a task, even if I am in pain, others will think I am lazy | 7.1 (2.0) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7.0 (1.6) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 2. | If I do not do the things, nobody will do them | 8.1 (1.9) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7.7 (1.5) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 3. | If I leave a task half done, even if I am in pain, I feel like I have not done enough | 7.9 (1.2) | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7.9 (0.8) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4. | Others think that I am taking advantage of my illness if I do not finish a task due to pain | 7.3 (1.8) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.8 (1.4) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 5. | When I feel a little better (I feel less pain), I am prudent and I do not take advantage to make up for lost time because I know I will feel worse later | 5.8 (3.4) | 3 | 7 | 9 | 5.0 (1.7) | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 (45%) | 11 (55%) |

| 6. | If I leave a task half done, even if I am in pain, I feel useless | 7.5 (2.1) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7.3 (0.7) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 7. | The pain and the amount of activity I do are not related | 3.6 (2.7) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 4.7 (1.9) | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) |

| 8. | I feel bad if I cannot do things because I feel pain, since my husband (mother, children, etc.) will have to do them | 7.1 (2.4) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (1.2) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 9. | If I do not do the things, they will not be done well | 6.7 (2.3) | 5 | 7 | 8 | 7.2 (1.1) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 17 (85%) | 3 (15%) |

| 10. | If I allow myself to be overcome by the pain, I will be able to do less and less | 6.4 (2.2) | 5 | 7 | 8 | 6.1 (0.8) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) |

| 11. | I feel that the best thing to do is finish my tasks, no matter how much pain I feel, in order to rest as soon as possible | 4.7 (2.8) | 2 | 4 | 7 | 4.2 (1.3) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 (15%) | 17 (85%) |

| 12. | Even if I continue the activity, the pain will not get worse | 2.6 (2.2) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.8 (1.1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) |

| 13. | If someone does things for me, they will also do them well | 3.8 (3.0) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3.7 (1.6) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) |

| 14. | If I stop every time the pain starts to get worse, I will not have enough time to do everything | 7.0 (2.3) | 6 | 7 | 9 | 7.0 (1.0) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 15. | I feel that if I finish my tasks despite the pain, I can rest sooner | 5.0 (2.7) | 3 | 6 | 7 | 4.7 (1.0) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 8 (40%) | 12 (60%) |

| 16. | Wanting to do everything myself has nothing to do with the fact that pain increases | 5.3 (2.8) | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5.0 (0.7) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) |

| 17. | I feel that if I do not finish a task, even if I am in pain, others will think I am taking advantage of my illness | 7.9 (1.5) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7.6 (1.6) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 18. | Leaving a task half done does not make me feel useless, especially if I feel pain | 4.4 (3.5) | 2 | 3 | 8 | 3.7 (1.6) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) |

| 19. | To make sure that things get done, I have to do them myself | 7.3 (2.0) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7.3 (1.3) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 20. | Others will not think that I am lazy if I do not finish my tasks, especially if I feel pain | 3.4 (2.5) | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3.6 (2.1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 (25%) | 15 (75%) |

| 21 | The pain does not depend on the amount of activity I do | 4.6 (2.4) | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5.0 (1.3) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) |

| 22. | If there is a task undone, I will not stop until I finish it, even if the pain gets worse | 6.8 (2.7) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (1.2) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 23. | If I let the pain overcome me, eventually I will be able to do even less | 7.6 (1.6) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7.8 (0.4) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 24. | If I stop every time the pain starts to get worse, I will have so many things to do that I will not have time to finish them all | 7.2 (2.2) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 7.2 (0.9) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 25. | If there is a task undone, I will not stop until I finish it, even if I know that afterwards I will feel a lot more pain | 7.1 (2.5) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.8 (1.1) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 17 (85%) | 3 (15%) |

| 26. | No matter how much pain I am in, if I do not finish a task, I am left with the feeling that I did not do as much as possible | 7.1 (2.3) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (0.9) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 27. | The pain does not get worse simply from carrying out an activity | 3.9 (2.2) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3.9 (0.6) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 (35%) | 13 (65%) |

| 28. | Doing things quickly does not make me feel more pain | 3.4 (2.5) | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3.0 (1.2) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 (25%) | 15 (75%) |

| 29. | I feel that if I stop doing a task every time the pain gets worse, I will not have enough time to do everything I have to do | 7.2 (1.8) | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7.1 (0.7) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 30. | Wanting to manage to do everything does not make me feel more pain | 4.3 (2.8) | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3.8 (1.4) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 (30%) | 14 (70%) |

| 31. | I feel that if I do not finish my tasks because I am in pain, others will understand me and they will not think I am taking advantage of my illness | 3.1 (2.9) | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3.3 (1.8) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) |

| 32. | When I feel a little better (I feel less pain), I cannot stop myself and I take advantage of lost time, despite knowing that I will feel worse later | 7.8 (2.2) | 7 | 8 | 10 | 7.7 (1.4) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 33. | I feel bad not doing things myself, even if I am in pain, because if I do not, my husband (mother, children, etc.) will have to do those things | 7.2 (1.9) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (1.3) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 34. | If I stop doing something every time the pain gets worse, tasks will accumulate and I will not have time to finish them | 7.4 (1.8) | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7.2 (1.0) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 35. | Leaving a task unfinished because I feel pain makes me feel useless | 8.5 (1.3) | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7.9 (1.3) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 20 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 36. | I prefer the satisfaction of being able to do things to the discomfort of feeling bad (feeling more pain) | 7.6 (2.6) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7.7 (1.4) | 8 | 8 | 8 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 37. | I have to do things myself so that they are done well | 7.5 (2.1) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 7.3 (1.2) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 38. | No matter how much I feel the pain getting worse, I do not stop until I am sure that everything is done | 6.6 (2.7) | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6.8 (1.0) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 39. | If I continue the activity, the pain will get worse | 6.0 (2.2) | 4 | 7 | 8 | 5.9 (1.1) | 6 | 6 | 7 | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) |

| 40. | If I know there is a task undone, I finish it despite knowing that I will feel more pain afterwards | 7.1 (2.6) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (1.3) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 41. | I do not feel more pain if I do things quickly | 3.9 (2.4) | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3.4 (1.1) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 (15%) | 17 (85%) |

| 42. | I think that, when I feel pain, it is better to stop working and start again after resting | 5.7 (2.7) | 3 | 5 | 9 | 5.6 (0.9) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 14 (70%) | 6 (30%) |

| 43. | I do not think letting myself be overcome by pain means that I will be able to do less and less | 4.1 (2.5) | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3.8 (1.5) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 (20%) | 16 (80%) |

| 44. | The pain depends greatly on the level of activity that I carry out | 6.5 (2.4) | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5.8 (1.2) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 15 (75%) | 5 (25%) |

| 45. | Even if I stop when the pain gets worse, I will have time to do my tasks | 3.3 (2.7) | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3.2 (1.0) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 (10%) | 18 (90%) |

| 46. | When I feel a little better (I feel less pain), I take advantage by making up for lost time even if I know that I will feel worse later | 7.3 (2.8) | 6 | 9 | 9 | 7.2 (1.3) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 18 (90%) | 2 (10%) |

| 47. | I think it is preferable to stop my activity when I feel the pain getting worse, even if it does not give me time to do all my tasks | 4.8 (3.2) | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4.6 (1.3) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 13 (65%) | 7 (35%) |

| 48. | If I do not finish a task because of pain, others will think I am lazy | 7.9 (1.6) | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7.4 (1.4) | 7 | 8 | 8 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 49. | I prefer having been able to do the things, despite feeling more pain because of it | 7.3 (2.4) | 7 | 8 | 9 | 6.9 (1.1) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 19 (95%) | 1 (5%) |

| 50. | If my husband (mother, children, etc.) have to do something that I cannot do because of pain, it does not make me feel bad | 4.7 (3.8) | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4.6 (1.8) | 3 | 5 | 5 | 8 (40%) | 12 (60%) |

| 51. | If the pain makes me leave a task unfinished, I know that I have done all I could do | 4.8 (3.0) | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4.7 (1.6) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 12 (60%) | 8 (40%) |

| 52. | The pain gets worse because I want to be able to do everything | 7.0 (2.3) | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6.4 (1.9) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 16 (80%) | 4 (20%) |

| 53. | Even though there is still something left to do, I stop the activity because I know that if I do not I will feel much more pain afterwards | 4.5 (2.7) | 2 | 4 | 7 | 4.1 (1.4) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 9 (45%) | 11 (55%) |

| 54. | I prefer giving up the satisfaction of doing things if I know that I am going to feel better (feel less pain) | 4.2 (3.1) | 1 | 3 | 7 | 4.2 (1.8) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) |

| 55. | The pain gets worse if I do things quickly | 4.9 (2.6) | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4.5 (1.4) | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 (25%) | 15 (75%) |

| 56. | If I feel the pain increasing, I stop doing the activity even if it is not finished | 4.8 (3.2) | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4.7 (1.2) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 16 (80%) | 4 (20%) |

| 57. | If I leave something undone, someone will do it for me | 3.2 (3.2) | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3.5 (1.8) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 (5%) | 19 (95%) |

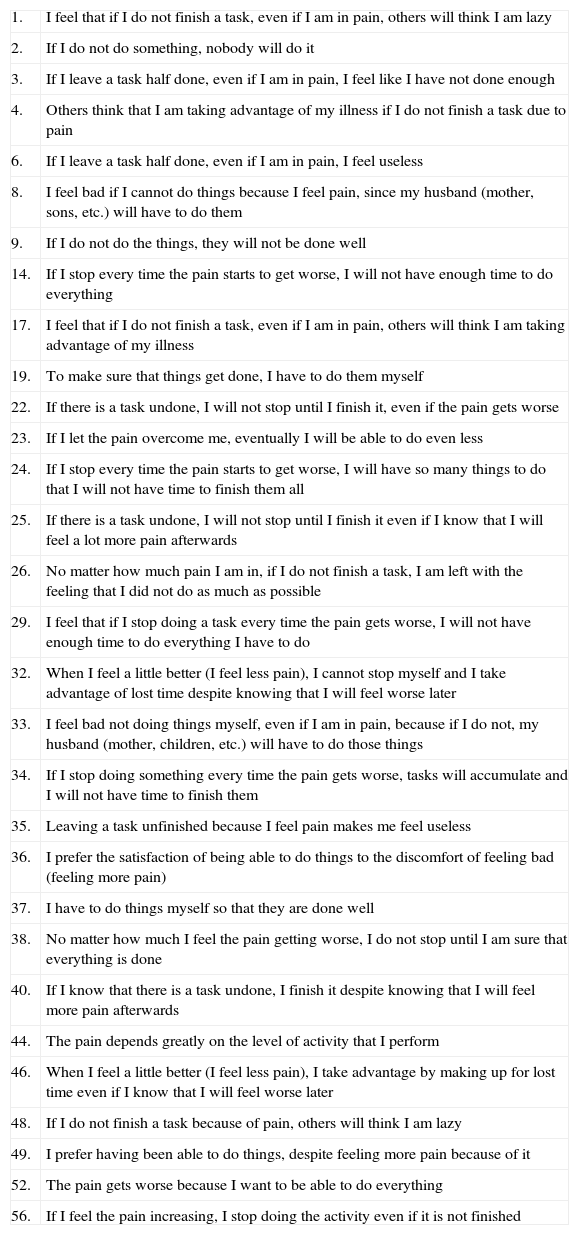

We excluded all items that at least 75% of the panel recommended eliminating, those that obtained a mean consensual assessment value less than 5 and those that did not reach a final agreement. The subsequent preliminary excessive activity questionnaire was composed of 30 items, which are shown in Annex 2.

DiscussionThe Delphi method allowed a broad, acceptable consensus to be reached regarding the content of the Clinical Questionnaire for Persistence of Activity in Fibromyalgia (CCPA-FM in Spanish) in 3 consultation rounds. It was recommended, without discrepancies, that 30 items be maintained. Nine of these items simply described the activity persistence pattern without mentioning the reasons that influenced such behaviour. Compared with the most recent definition of the different dimensions of avoidance, persistence and pacing through a factorial analysis of the main instruments used to measure activity patterns and pain coping strategies,18 5 of these items describe the pattern of activity persistence for the purpose of finishing tasks and activities despite the pain. Kindermans et al.18 have labelled this pattern as “task-contingent persistence”. This pattern has also been associated with a lower functional incapacity. Two items contained statements that acknowledge the relationship between the increase in pain and the activity persistence, which would allow both items to be correlated with the factor called “task-contingent persistence,” which does not seem to be very relevant to functional incapacity or depressive symptomatology. The other 2 items described a pattern of increase in activity prompted by reduced pain intensity, which in turn produces a rebound effect regarding the pain. This is similar to the “excessive persistence” factor, which has been associated with greater functional incapacity and greater depressive symptomatology even after controlling for the effect of pain intensity.

Despite providing valuable information regarding behaviour patterns in patients with fibromyalgia, none of these items provided information on the reasons why patients sustain this behaviour. Consequently, although the items make it possible to verify the presence of a pattern of activity persistence, they provide no useful information for its modification.

Of the items maintained by the group of experts that included beliefs justifying activity persistence, 7 correlated maintaining the activity despite increasing pain with avoiding negative emotions related to unsatisfactory execution of that activity. Specifically, these negative sensations are the feeling of not having done enough, feeling useless and having pangs of guilt. These items would align with the decision rule, defined by Vlaeyen et al7 as “as many as you can”, which determined that the person did not interrupt the activity, not even with increasing pain, until he or she felt satisfied with its execution. Unfortunately, there is only 1 unpublished study, carried out in a non-clinical setting, regarding the relationship between this decision rule and fibromyalgia patients’ moods,19 with discordant results according to the study subjects’ intensity of pain.

The rest of the items seemed to describe 3 groups of beliefs that have yet to be defined. Six items justified activity persistence in order to avoid short-term (not fulfilling obligations) and long-term (losing functional capacity) negative consequences. Four items based activity persistence on not having help or not having quality help (tasks will not be done well if not done by the patient). Finally, 4 items based activity persistence on avoiding social disapproval.

Even though acceptable consensus was obtained for 41 of the 57 items addressed, agreement was not reached for 16 items. Consequently, the definitive decision of whether they would be maintained in the final questionnaire would be made according to their contribution to the consistency and validity of the items selected by the group of experts.

The thoughts responsible for activity persistence despite increasing pain constitute automatic processing of information based on previous experience; such thoughts thus represent a subliminal process different from deliberate conclusions that come from reflection.20 Access to this subliminal content requires the application of guided discovery techniques and its modification is resistant to rational modification through increased therapy or provision of information. The CCPA-FM could therefore be a useful instrument for measuring the beliefs that impede modification of the activity persistence pattern in fibromyalgia and for prospectively evaluating its relationship with evolution of pain symptoms. Likewise, the CCPA-FM would make it possible to have fewer guided discovery sessions. It would also be possible, from the first treatment phases, to plan corrective experiences that are specific, individualised and focused on modifying the subjectively greater cost-effectiveness associated with maintaining activity persistence (such as avoiding social disapproval).

One clinical trial already observed that the combination of medical and cognitive-behavioural treatment, adjusted for each behaviour pattern (avoidance or persistence), was more effective for sciatic pain than non-specific psychological treatment or standard medical treatment.21 Similar results are starting to be obtained in fibromyalgia treatment.13,22 Furthermore, it is possible that a therapeutic strategy that has demonstrated effectiveness in patients with a pattern of fear/anxiety and activity avoidance (progressive recovery of the activity, live exposure)23,24 may not be so effective in patients with a preferential activity persistence pattern. The CCPA-FM could be an effective tool for discriminating between patient groups and individualising treatment.

The preliminary CCPA-FM item selection process had several limitations. Firstly, the item selection process was performed based on analysis of guided discovery interviews and the cognitive records of patients with fibromyalgia admitted into a tertiary unit. It is therefore possible that the bias in sample selection had defined content that was not truly characteristic of the patients treated in other levels of care. Consequently, it is necessary to include patients treated in primary and hospital care.

During the process, experts who abandoned the study (the figure was not statistically significant) were primarily from the family medicine health specialty. Therefore, even though the number of experts remained within the recommended number for a Delphi Study,25 it was not possible to rule out a bias due to the majority presence of rheumatologists and clinical psychologists. Likewise, the absence of psychiatry specialists in the expert group could also have contributed to a potential bias related to the predominance of a certain specialty.

In general, the Delphi method has been criticised for the possibility that its results run the risk of not being representative or reliable (reaching a consensus does not necessarily mean that the conclusions made are correct). The results of this study should thus be considered as a starting point for the process of assessing CCPA-FM psychometric properties. Given that this instrument attempts to measure the thoughts that sustain an excessive persistence pattern, and also keeping in mind the inconsistencies and limitations of self-applied questionnaires that measure activity,26–28 it would be reasonable to introduce actigraph measurements in the validation process. They facilitate assessment of the relationship, and especially of the precedence, between modification of thoughts that supposedly maintain the excessive persistence pattern, the objective activity and patient clinical state.

In conclusion, there is solid evidence of the importance of the fear/anxiety model and avoidance of the activity in maintaining pain and incapacity in fibromyalgia. Indication of the existence of an opposite, although not incompatible, model based on activity persistence has recently been found. Determining the relevance of this new model and designing treatments for its modification can be encouraged by the availability of an instrument that allows us to precisely evaluate the reasons for fibromyalgia patients’ difficulty in relaxing this behaviour pattern despite the fact that they themselves and the individuals around them are aware of its adverse effect on the maintenance of their disease.

Ethical disclosuresHuman and animal protectionThe authors declare that no experiments were performed with humans or animals for this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

| Dr Eva Baillès Lázaro | Universitat Pompeu Fabra |

| Dr Maite Bel Villar | Hospital Fundació Mollet |

| Dr Josep Blanch Rubió | Hospital del Mar |

| Dr Jordi Carbonell Abelló | Hospital del Mar |

| Dr Manel Ciria Recasens | Parc de Salut Mar |

| Dr Mònica Coll Batet | Hospital de Mataró |

| Mrs Maria Àfrica Cruz Garcia | Hospital del Mar—Parc de Salut Mar |

| Dr Anna María Cuscó Segarra | Clinica CIMA. Institut Ferran de Reumatologia |

| Dr Jimena Fiz Viola | Spactiva |

| Dr Ana Isabel Liberal Planas | Manso 2b Via Roma |

| Dr María José Martín Martín | Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa |

| Dr María Teresa Martínez Mendoza | ABS Via Roma Barcelona |

| Dr Silvia Martínez Pardo | Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa |

| Dr Juan Manuel Nieto Somoza | CAP Can Rull |

| Mrs Nuria Palau Ortega | Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa |

| Dr Josep Maria Peri Nogués | Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

| Dr Violant Poca Dias | Clinica CIMA. Institut Ferran de Reumatologia |

| Dr Georgina Salvador Alarcón | Hospital Universitari Mútua Terrassa |

| Dr Núria Segalés Plana | Consorci Sanitari del Maresme |

| Dr Antoni Sisó Almirall | CAP Les Corts- Unitat d’Investigació CAPSE-Gesclínic. IDIBAPS |

| Mr Àngel Soto Lumbreras | Consorci Sanitari Anoia |

| Dr Ester Tarradas Puértolas | Cap Barceloneta. Pam S. L. |

| Mr Daniel Vega Moreno | Hospital d’Igualada |

| 1. | I feel that if I do not finish a task, even if I am in pain, others will think I am lazy |

| 2. | If I do not do something, nobody will do it |

| 3. | If I leave a task half done, even if I am in pain, I feel like I have not done enough |

| 4. | Others think that I am taking advantage of my illness if I do not finish a task due to pain |

| 6. | If I leave a task half done, even if I am in pain, I feel useless |

| 8. | I feel bad if I cannot do things because I feel pain, since my husband (mother, sons, etc.) will have to do them |

| 9. | If I do not do the things, they will not be done well |

| 14. | If I stop every time the pain starts to get worse, I will not have enough time to do everything |

| 17. | I feel that if I do not finish a task, even if I am in pain, others will think I am taking advantage of my illness |

| 19. | To make sure that things get done, I have to do them myself |

| 22. | If there is a task undone, I will not stop until I finish it, even if the pain gets worse |

| 23. | If I let the pain overcome me, eventually I will be able to do even less |

| 24. | If I stop every time the pain starts to get worse, I will have so many things to do that I will not have time to finish them all |

| 25. | If there is a task undone, I will not stop until I finish it even if I know that I will feel a lot more pain afterwards |

| 26. | No matter how much pain I am in, if I do not finish a task, I am left with the feeling that I did not do as much as possible |

| 29. | I feel that if I stop doing a task every time the pain gets worse, I will not have enough time to do everything I have to do |

| 32. | When I feel a little better (I feel less pain), I cannot stop myself and I take advantage of lost time despite knowing that I will feel worse later |

| 33. | I feel bad not doing things myself, even if I am in pain, because if I do not, my husband (mother, children, etc.) will have to do those things |

| 34. | If I stop doing something every time the pain gets worse, tasks will accumulate and I will not have time to finish them |

| 35. | Leaving a task unfinished because I feel pain makes me feel useless |

| 36. | I prefer the satisfaction of being able to do things to the discomfort of feeling bad (feeling more pain) |

| 37. | I have to do things myself so that they are done well |

| 38. | No matter how much I feel the pain getting worse, I do not stop until I am sure that everything is done |

| 40. | If I know that there is a task undone, I finish it despite knowing that I will feel more pain afterwards |

| 44. | The pain depends greatly on the level of activity that I perform |

| 46. | When I feel a little better (I feel less pain), I take advantage by making up for lost time even if I know that I will feel worse later |

| 48. | If I do not finish a task because of pain, others will think I am lazy |

| 49. | I prefer having been able to do things, despite feeling more pain because of it |

| 52. | The pain gets worse because I want to be able to do everything |

| 56. | If I feel the pain increasing, I stop doing the activity even if it is not finished |

Please cite this article as: Torres X, et al. ¿Por qué las personas con fibromialgia persisten en la actividad a pesar del dolor creciente?: estudio Delphi sobre el contenido del Cuestionario Clínic de Persistencia en la Actividad en Fibromialgia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2013;6:33–44.