Caracterizar los cuerpos desmembrados o descuartizados abordados en la Unidad Básica Medellín del Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (INMLCFM) y establecer los factores asociados con su identificación.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de corte transversal de registros de cuerpos descuartizados o desmembrados que ingresaron al INMLCFM entre los años 2013 y 2017. Para evaluar las variables asociadas a la identificación de los cadáveres descuartizados o desmembrados se aplicó el test estadístico de chi-cuadrado.

ResultadosEn el periodo de estudio se encontraron un total de 54 cadáveres, los factores asociados con la identificación de los cuerpos fueron cuerpos de personas mayores de 26 años OR 1,22 IC95% (1.04–1.43) valor p 0.043; los cuerpos encontrados en sitios únicos OR 1,22 IC95% (1.04–1.43) valor p 0.043. Mientras que los factores que se asociaron con una mayor probabilidad de no lograr una identificación fueron ser hombre OR 1,14 IC95% (1.02–1.27) valor p 0.435 y los cuerpos descuartizados OR 1,14 IC95% (1.02–1.28) valor p 0.354.

DiscusiónLa identificación de cuerpos descuartizados y desmembrados es un reto para el médico forense colombiano, pero conocer los factores asociados con su identificación favorece su adecuado abordaje lo que mejoraría este proceso.

To characterise the dismembered bodies dealt with in the Medellín Basic Unit of the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (INMLCF) and establish the factors associated with their identification.

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study of records of dismembered bodies that entered the National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences of Medellin between 2013 and 2017. To evaluate the variables associated with the identification of dismembered bodies, using the chi-square statistical test.

ResultsA total of 54 bodies were found during the study period, the factors associated with the identification of the bodies were bodies of people older than 26 years OR 1.22 95% CI (1.04–1.43) p value .043 and bodies found in unique sites OR 1.22 95% CI (1.04–1.43) p value .043. The factors that were associated with a higher probability of not achieving identification were being male OR 1.14 95% CI (1.02–1.27) p value .435 and dismembered bodies OR 1.14 95% CI (1.02–1.28) p value .354.

DiscussionThe identification of dismembered bodies is a challenge for the Colombian coroner, but knowing the factors associated with their identification enables an appropriate approach which would improve this process.

Criminal mutilation is the intentional fragmentation of a cadaver that may be performed due to several reasons (to transport the body from the primary scene, to prevent identification of the dead individual or to send a message, etc.).1

Although dismemberment and quartering are not the most frequent findings in Forensic Medicine, cases have been reported from around the world, and in Colombia it is a subject of conversation in various cities. It has been reported that sharp instruments able to cut a body into pieces are used in these cases, such as hand saws, chain saws and knives which leave marks that could be used in an investigation. The main aim is said to be to hide the body and conceal the homicide, or to prevent the identification of the dead individual, or to send a message to an enemy. A premise when talking of dismembering in the forensic context is that it generally refers to criminal acts, excluding accidental events such as traffic accidents.1,2

Colombia is a country that has suffered a great deal due to violence. According to the figures reported by the Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses (INMLCF), which covers this material in the country, in its journal Forensis, in the year 2016 there were 25,438 violent deaths (homicides, traffic accidents, accidental deaths, suicides and deaths with indeterminate causes) and 25,381 such deaths in 2017. More specifically, 11,532 homicides were reported in the year 2016 and 11,373 in 2017, at a rate of 23.66 per 100,000 inhabitants in the first case, and 23.07 per 100,000 inhabitants in the second case.3 More recent data taken from INMLCF monthly statistical bulletins reports 11,297 homicides in 2018 and 3,637 from January to April 2019.4

Decree 786 of 1990 by the Colombian Ministry of Public Health governs the performance of medical-legal as well as clinical necropsies in national territory to investigate the causes and circumstances of deaths. Medical-legal necropsies are performed for reasons arising from judicial investigations; according to article 6 they are obligatory for cases of homicide or suspected homicide, suicide or suspected suicide, when it is necessary to distinguish homicide from suicide, accidental death or suspicion of the same, cases in which the cause of death is unclear or when an autopsy is necessary to help in the identification of a body.5

Article 5 of the same decree sets out the objectives to be met in medical-legal necropsies, among which it underlines contributing to the identification of a cadaver.5 Cadavers that have been dismembered or quartered, among others, hinder this objectives due to the intention of the killer to hid the crime and its victim, making the use of such bodies more complicated for forensic doctors; this premise is based on circular number 8 issued by the INMLCF.6

Given the panorama described above, and as few works exist worldwide that cover the study of bodies of this type, a study was undertaken that aimed to characterise the dismembered or quartered bodies seen in Medellin Basic Unit of the INMLCF, establishing the factors which are associated with the identification of the same.

MethodologyType of studyAn observational transversal study was carried out of the quartered or dismembered bodies that were admitted to the Medellin INMLCF from 2013 to 2017, together with the factors associated with their identification.

The North West Regional INMLCF of Colombia is in charge of attending to medical-legal necropsy cases in the Departments of Antioquia, Chocó and Córdoba, which account for approximately 18.5% of the total number of procedures carried out in the country. Medellin lies within the Department of Antioquia (Antioquia Section Management) and is its capital city, as does the metropolitan area of Aburrá Valley, which is composed of 9 nearby municipalities.

This study was undertaken based on cases of dismembered and quartered bodies from the metropolitan area of Aburrá Valley, together with some cases from the Department of Antioquia that were considered complex. As there are no Legal Medicine Units in the whole Department, these were transferred to the Central Office in Medellin.

Sources of information and data gatheringData access was gained through Medellin INMLCF before it was entered into the Disappeared Individuals and Cadavers Data System Network (SIRDEC), together with access to the corresponding case file where the cases of the quartered or dismembered bodies presented during the study period were reviewed. Information was thereby obtained on: the sex, age, origin (the metropolitan area or outside the same), occupation (employed or unemployed), location of discovery (single or multiple), cause of death, vital status at the time cutting took place, type of mutilation (dismemberment or quartering), marks left by tools (present or absent), wrappings, and whether the body were complete or incomplete. Finally the outcome in terms of identification of the body was considered as a variable.

This information was used to build a database that contained the variables of interest and which was subjected to an exploratory analysis to identify lost data and atypical values, as well as to verify the quality of the information.

Bodies found within the metropolitan area were understood to correspond to those found in one of the ten municipalities within this area (Medellin, Barbosa, Girardota, Copacabana, Bello, Itagüí, Sabaneta, Envigado, La Estrella and Caldas), while those found outside this area were detected in another municipality. The location of discovery corresponded all of the body parts found in one or several points.

Vital status at the time of cutting refers to whether the individual was alive or dead at the time of mutilation. Respecting the type of mutilation, quartering was understood to refer to a body that had been mutilated in areas of the body other than the joints, while dismemberment was understood to refer to bodies that had been mutilated at the joints; if tool-marks were present at the cuts, the type of mark left was identified.

Data analysisDescriptive analysis of the study variables was undertaken, calculating frequencies and proportions for each one of the variables included. The chi-squared test was used to evaluate the variables which were associated with the identification of quartered or dismembered cadavers, and a P value <.05 was understood to indicate significance. Version 24 of SPSS software was used for data processing, licenced by Tecnológico, Antioquia.

Ethical considerationsThis research was approved ethically by the Ethics Committee of the Tecnológico de Antioquia - Institución Universitaria.

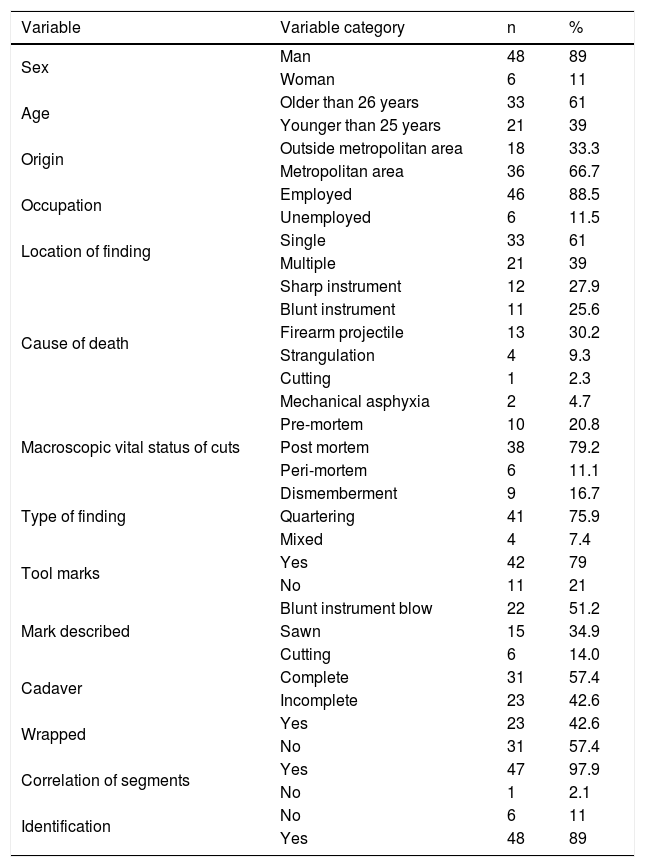

ResultsA total of 54 cadavers were found during the study period. The majority of them were male (89%; 48), above the age of 26 years (61%; 33) and found in the metropolitan area (66.7%; 36). Respecting the location where bodies were found, the majority of body parts were found in a single place (61%; 33) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics and types of trauma of the quartered or dismembered bodies admitted to Medellin INMLCF from 2013 to 2017.

| Variable | Variable category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Man | 48 | 89 |

| Woman | 6 | 11 | |

| Age | Older than 26 years | 33 | 61 |

| Younger than 25 years | 21 | 39 | |

| Origin | Outside metropolitan area | 18 | 33.3 |

| Metropolitan area | 36 | 66.7 | |

| Occupation | Employed | 46 | 88.5 |

| Unemployed | 6 | 11.5 | |

| Location of finding | Single | 33 | 61 |

| Multiple | 21 | 39 | |

| Cause of death | Sharp instrument | 12 | 27.9 |

| Blunt instrument | 11 | 25.6 | |

| Firearm projectile | 13 | 30.2 | |

| Strangulation | 4 | 9.3 | |

| Cutting | 1 | 2.3 | |

| Mechanical asphyxia | 2 | 4.7 | |

| Macroscopic vital status of cuts | Pre-mortem | 10 | 20.8 |

| Post mortem | 38 | 79.2 | |

| Peri-mortem | 6 | 11.1 | |

| Type of finding | Dismemberment | 9 | 16.7 |

| Quartering | 41 | 75.9 | |

| Mixed | 4 | 7.4 | |

| Tool marks | Yes | 42 | 79 |

| No | 11 | 21 | |

| Mark described | Blunt instrument blow | 22 | 51.2 |

| Sawn | 15 | 34.9 | |

| Cutting | 6 | 14.0 | |

| Cadaver | Complete | 31 | 57.4 |

| Incomplete | 23 | 42.6 | |

| Wrapped | Yes | 23 | 42.6 |

| No | 31 | 57.4 | |

| Correlation of segments | Yes | 47 | 97.9 |

| No | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Identification | No | 6 | 11 |

| Yes | 48 | 89 |

In 55.4% (24) of cases it was found that the use of sharp or blunt instruments was the cause of death (SBI, sharp or blunt instruments), while in 30.2% (13) of cases death was caused by a firearm projectile, and the other cases corresponded to mechanical asphyxiation. The majority of cuts were made post mortem (79.2%; 38), and the predominant type of mutilation was quartering (75.9%; 41). It was also found that in the majority of cases marks left by tools were described (79%; 42); the mark described the most often was one caused by a short blunt instrument (51.2%; 22). The body was complete in 57.4% of cases (31) and had no wrappings (Table 1).

It was found that identification was made in the majority of cases (89%; 48); this was not achieved in only 6 cases (11%), i.e., for each unidentified body, 8 were identified. The majority of reliable identifications were made using fingerprint checks (75%; 36), followed by genetic checks (14.6%; 7), various methods in 6.3% (3) and finally by checking dental records in 4.2% (2) cases (Table 1).

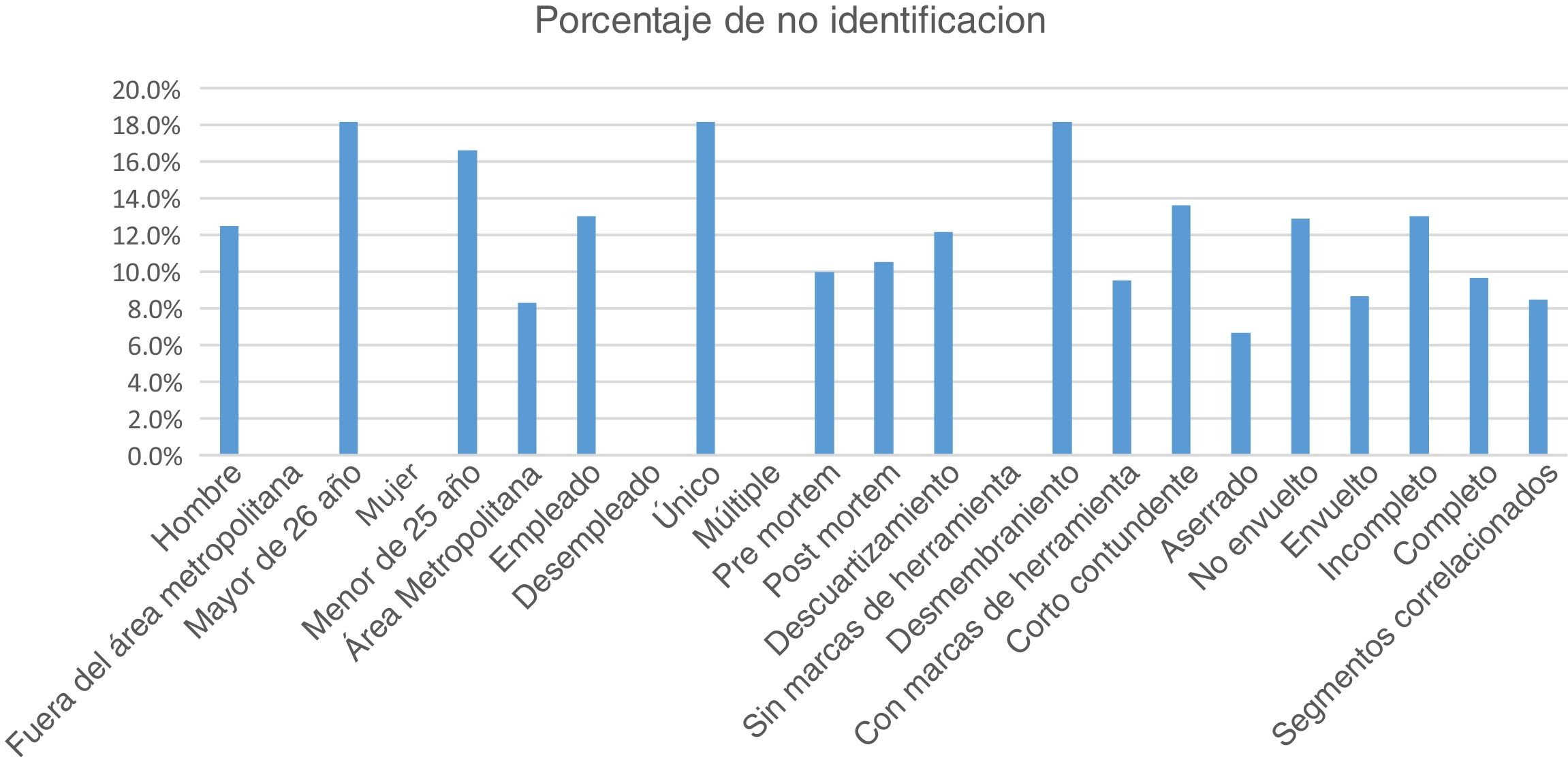

The factors which were associated with a higher percentage of non-identification (18%) were being over the age of 26 years, being found in a single location and not having any tool marks; female victims, those aged under 25 years and the dismembered victims were all identified (Fig. 1).

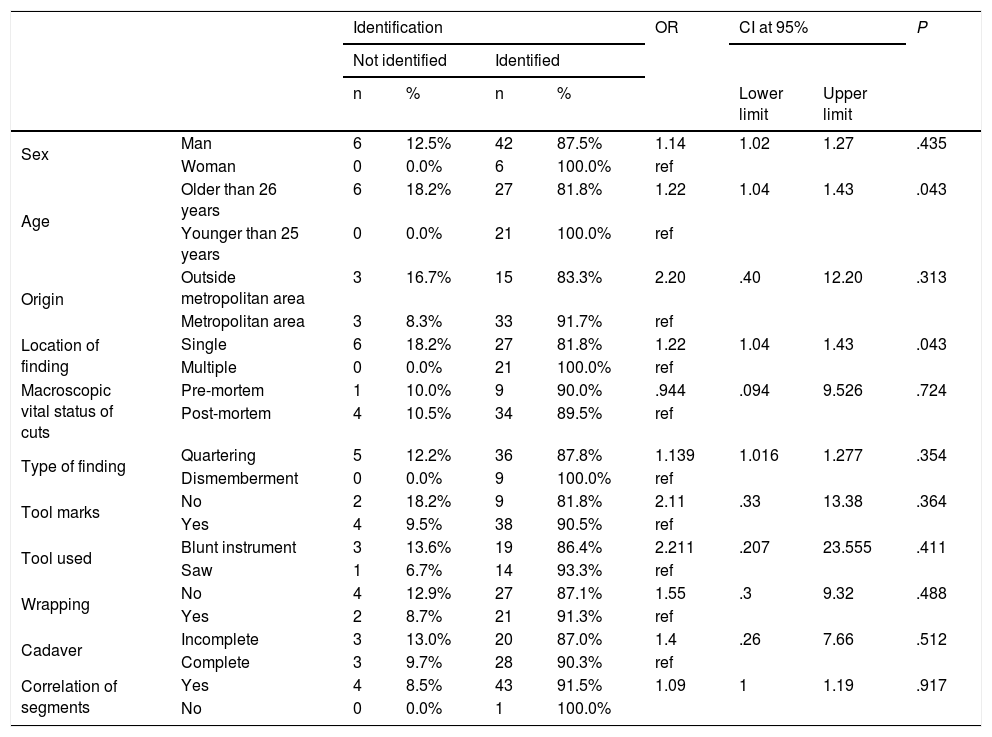

In connection with the factors that were associated with the identification of the quartered or dismembered bodies that entered the Medellin INMLCF from 2013 to 2017, the bodies of individuals aged over 26 years had a 22% higher probability of not being identified, compared with the bodies of those aged under 26 years (OR: 1.22; CI 95%: 1.04–1.43; P=.043). The bodies found in a single location had a 22% higher probability of not being identified, compared with the bodies found in multiple locations (OR: 1.22; CI 95%: 1.04–1.43; P=.043) (Table 2).

Sociodemographic factors and types of trauma associated with the identification of quartered or dismembered bodies admitted to Medellin INMLCF from 2013 to 2017.

| Identification | OR | CI at 95% | P | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not identified | Identified | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Sex | Man | 6 | 12.5% | 42 | 87.5% | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.27 | .435 |

| Woman | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 100.0% | ref | ||||

| Age | Older than 26 years | 6 | 18.2% | 27 | 81.8% | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.43 | .043 |

| Younger than 25 years | 0 | 0.0% | 21 | 100.0% | ref | ||||

| Origin | Outside metropolitan area | 3 | 16.7% | 15 | 83.3% | 2.20 | .40 | 12.20 | .313 |

| Metropolitan area | 3 | 8.3% | 33 | 91.7% | ref | ||||

| Location of finding | Single | 6 | 18.2% | 27 | 81.8% | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.43 | .043 |

| Multiple | 0 | 0.0% | 21 | 100.0% | ref | ||||

| Macroscopic vital status of cuts | Pre-mortem | 1 | 10.0% | 9 | 90.0% | .944 | .094 | 9.526 | .724 |

| Post-mortem | 4 | 10.5% | 34 | 89.5% | ref | ||||

| Type of finding | Quartering | 5 | 12.2% | 36 | 87.8% | 1.139 | 1.016 | 1.277 | .354 |

| Dismemberment | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 100.0% | ref | ||||

| Tool marks | No | 2 | 18.2% | 9 | 81.8% | 2.11 | .33 | 13.38 | .364 |

| Yes | 4 | 9.5% | 38 | 90.5% | ref | ||||

| Tool used | Blunt instrument | 3 | 13.6% | 19 | 86.4% | 2.211 | .207 | 23.555 | .411 |

| Saw | 1 | 6.7% | 14 | 93.3% | ref | ||||

| Wrapping | No | 4 | 12.9% | 27 | 87.1% | 1.55 | .3 | 9.32 | .488 |

| Yes | 2 | 8.7% | 21 | 91.3% | ref | ||||

| Cadaver | Incomplete | 3 | 13.0% | 20 | 87.0% | 1.4 | .26 | 7.66 | .512 |

| Complete | 3 | 9.7% | 28 | 90.3% | ref | ||||

| Correlation of segments | Yes | 4 | 8.5% | 43 | 91.5% | 1.09 | 1 | 1.19 | .917 |

| No | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 100.0% | |||||

Male cadavers (OR: 1.14; CI 95%: 1.02–1.27; P=.435) or those that had been quartered (OR: 1.14; CI 95%: 1.02–1.28; P=.354) had a higher probability of not being identified. Nevertheless, these differences were not statistically significant, and this was probably due to loss of statistical test power because in some categories (such as female bodies) there were no cases of non-identification (Table 2).

DiscussionFew studies at an international level have covered this problem, and this work is the first to study the characteristics that may aid or hinder the identification process in cases of this type; it is also the first study to cover this problem in Colombia.

Few cases of dismembered bodies have been reported in the literature worldwide, and there are even fewer major studies with series of cases. Among the few that were found, one was undertaken in Finland, where 13 cases were reported in 10 years;7 one was found in Korea, with 65 cases in 17 years;8 another one in Switzerland covered 22 cases in 30 years;9 another in Cracow with 23 cases in 38 years,10 and two others: one in New York with 55 cases in 22 years11 and another one in Germany, with 51 cases in 58 years.12 It is striking that these studies covered a long period of time for analysis, showing that cases of this type are really not very common in everyday forensic work, and that a large number of years have to be studied for results to be reported to the scientific community.

The study carried out in Finland,7 where 13 cases were reported, states that there were 3 (23.07%) cases involving women and 10 (79.92%) with men, which is comparable to the study presented here, where 6 (11.1%) cases involved women and 48 (88.8%) men. They also remark that 8 (61.52%) cases were found in a single location, which is very similar to our study, where this occurred in 33 (61.11%) cases.7 However, it is contrary to the findings of the study undertaken in Germany12 of 51 cases: 32 (62.74%) women and 19 (37.25%) men, which is the opposite of our findings, where 6 (11.1%) cases were women and 48 (88.8%) were men. This may be explained by the intentions of the perpetrators, who often belonged to criminal gangs. The majority of these gangs were composed of men who wanted to use their actions to send messages between criminal organisations, so that it was not so common to find body parts at different geographical locations.

Respecting the marks left by tools, the German study12 found 36 cases of cuts made by a sharp instrument and 26 cuts made by a saw. However, some cases had both types of marks, and this is similar to our study, where 38 cases had marks left by a sharp instrument and 15 had saw marks. It is common to find tool marks that are compatible with those left by sharp instruments, as often elements are used which are easily accessible.

Regarding the causes of death, the German study12 describes 15 (29.41%) cases in which the cause of death was a sharp instrument, while in 8 (15.68%) cases it was caused by a blunt instrument, in 2 (3.92%) cases it was due to a firearm projectile and in 13 cases (25.49%) it was caused by mechanical asphyxiation.12 In our study 24 (44,44%) cases were due to a sharp instrument, in 13 (24.07%) cases death was caused by a firearm projectile and in 6 cases (11.11%) the cause was mechanical asphyxiation. The deaths caused by different uses of “sharp instruments” may be linked with the ease of access to these items, as was described in the previous paragraph.

A study undertaken in New York11 reported 55 cases: in 27 (49.09%) of these the body was found complete, and in 28 (50.90%) it was incomplete; the corresponding figures for our study were 31 (57.40%) complete bodies and 23 (42.59%) incomplete ones, with an average in the New York study of 2.5 dismembered bodies per year and a maximum of 8 cases in 2005 and 0 in 2016.11 In our study an average of 10.8 dismembered bodies were found per year, with a maximum of 16 cases in 2017 and a minimum of 8 cases in 2014. The percentage of complete and incomplete findings is very similar in the study undertaken in New York City: almost 50% each year; nevertheless, in the Colombian study they differ, as the majority of findings correspond to complete bodies, showing that the objective was not to prevent the identification of the body. On the other hand, there is a visible difference between the numbers of cases per year: in our study no year was found in which there were no cases, so it is evident that practices of this nature occur in our environment, and although they are not detected every day, they do form a part of local forensic medical work.

Taking the findings of our study into account regarding the identification process, it was only impossible to achieve identification in 6 of the 54 cases; the factors associated with non-identification of the quartered or dismembered bodies admitted to Medellin INMLCF from 2013 to 2017 were that they were male, older than 26 years, quartered and found at a single location. The number of bodies which were identified shows that the identification techniques used in Colombia are effective in the majority of cases; however, identification was not possible in a few cases, and these corresponded to men over the age of 26 years. This finding is in agreement with the total number, the majority of whom were men and possibly involved in matters where the chief goal was to prevent the identification of the victim; the unidentified bodies were predominantly found at a single location and had been quartered. They also often corresponded to incomplete bodies that lacked anatomical parts that would be necessary for easy identification (the head and hands).

The main limitation of this study centres on the low number of cases, as this is not a common finding in forensic medicine, so that it is not possible to obtain a sufficient volume to make associations that would give rise to statistically significant findings; notwithstanding this, it is important to underline that this study covers one of the largest series of cases at an international level in such a short time.

As Antia et al.13 stated, the forensic sciences must play a humanitarian role, and this study fulfils this precept as it covers a problem that affects civil society, in the context of the appropriate treatment of mutilated bodies.

This work objectively describes the phenomenon of mutilated bodies in a part of Colombia (the Aburrá Valley); over and above the urban myths in which almost any strange finding in a body is immediately associated with a body that has been quartered, this phenomenon was found to be present and to give rise to an everyday challenge for forensic doctors, to learn how to approach it and work in a rigorous and professional manner.

Because little research has taken place in the past into this subject, this study opens a door to larger ones in terms of duration or the coverage of a larger part of national territory, to continue investigating this situation so that it can be described for the forensic and judicial community.

This study makes it possible to conclude that cases of quartered and dismembered bodies are a tangible part of forensic medical practice in Colombia. There are factors that may favour or hinder identification in cases of this type, and they include the age and sex of the victim, the location of the body and type of mutilation. It is therefore necessary to include these factors in our approach, as references to improve identification processes and thereby offer the judicial authorities technical and scientific support to fully achieve the objectives of medical and legal necropsies set by current law. However, this field has hardly been studied, so that further research is necessary, including a series over a longer period of time, with broader geographical scope and collecting more data during the performance of medical-legal necropsies.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vásquez Guarín C, García Ospina J, Castaño CFM. Factores asociados a la identificación de cuerpos descuartizados o desmembrados en Medellín (Colombia). Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2021;47:9–15.