Nowadays, diving is a safe practice and fatalities are uncommon. The main cause of death reported is drowning but others have been described, such as, those secondary to the biophysical foundations that govern the hyperbaric environment, like arterial gas embolism or decompression illness. Because of this, multidisciplinary investigation is essential for elucidating the cause of death.

A practical guideline is proposed to systematise and direct the collection of technical-police and medical-forensic data by the different professionals involved to correctly identify all events related to the accident.

It consists of 2 well-differentiated blocks which shows the sequence to choose the most appropriate autopsy techniques and complementary tests to carry out a complete analysis of each diving fatality, all aimed to avoid overdiagnosis of deaths by drowning.

This way, it will be possible to identify risk factors or unsafe behaviours about which to develop prevention measures.

Actualmente, el buceo es una actividad segura y las muertes son escasas. La principal causa de muerte es la asfixia por sumersión, aunque se han descrito otras causas secundarias a los fundamentos biofísicos que regulan el medio hiperbárico, como el embolismo gaseoso arterial o la enfermedad descompresiva. Por este motivo, la investigación multidisciplinar es esencial para averiguar la causa de muerte.

Se propone una guía práctica que sistematiza y dirige la recogida de datos técnico-policiales y médico-forenses por parte de los diferentes profesionales involucrados para poder identificar correctamente todos los eventos implicados en el accidente. Consiste en dos bloques que muestran una secuencia para elegir la técnica de autopsia y pruebas complementarias más apropiadas para llevar a cabo un estudio completo de cada caso y así evitar el sobrediagnóstico de muertes por sumersión. De esta manera, será posible identificar factores y conductas de riesgo para desarrollar medidas de prevención.

Diving is defined as an underwater activity in which a person remains underwater in a hyperbaric environment, either with systems that enable the exchange of a mixture of gases, with systems that facilitate breathing, or without the aid of such systems.1 While statistically it is a safe activity,2 it is clear that there is no such thing as zero risk and that diving can sometimes result in the death of the diver. It has been estimated that in the United States the number of fatalities remains constant at approximately 2 deaths for every 100 000 dives.3 There are no published data regarding diving mortality in Spain, with the exception of the province of Girona (Catalonia), where there is approximately 1 death per 100 000 dives per year.4

According to the Criminal Procedure Act currently in force in Spain, these deaths shall be presumed to be criminal or violent and, as such, shall prompt a formal legal proceeding and investigation, within the framework of which the forensic medical examiner shall conduct a forensic post-mortem investigation.

Such deaths can have a number of different causes related or unrelated to the hyperbaric environment4 (Table 1). While the leading cause of death is submersion asphyxia,5,6 other causes have been reported that are secondary to the biophysical fundamentals of gas behaviour, such as pulmonary barotrauma,7–9 decompression sickness,10 or poisoning by gases or other contaminants contained in scuba diving tanks.6 Likewise, other common causes of death not directly related to the hyperbaric environment should also be kept in mind, such as decompensation of a pre-existing illness7,11 or the presence of trauma.12 Pulmonary oedema attributable to immersion, which is not explicitly included in the previously mentioned groups and is a diagnosis of exclusion, deserves special mention, given that it is a little known and, in all likelihood, underdiagnosed entity.13

In terms of forensic aetiology, all possible forms have been reported. Accordingly, despite the fact that accidental deaths are widely highlighted,6 other possible aetiologies must be contemplated and, while they are described as being rare, homicide by third parties must always be ruled out.4,14 In turn, suicide as the manner of death, albeit more common, is equally scarce and in most cases is associated with a pre-existing mental illness14,15 or with the use of toxic substances.

Because deaths during diving are unusual, its environmental and technical peculiarities and the highly specific nature of some of its causes may result in a biased approach and an incomplete or erroneous study leading to an overdiagnosis of deaths due to immersion.16 It is therefore imperative that a model of collaboration be implemented to consolidate an interdisciplinary approach among professionals specialising in the various fields involved.11,16

This is precisely the line defined by the leading international guidelines published on the subject,11,16–18 in which the steps to be followed when investigating deaths during diving are defined and developed, and that have deal largely with the circumstances of the event, background of the deceased, diving equipment, and autopsy, while at the same time providing standard data collection forms for each one. Other authors19 underscore the need to conduct a multidisciplinary investigation that is as systematic as possible, that also includes the police report, the diver's experience, the analysis of the equipment, and the autopsy report with the description of any ad hoc techniques. All these contributions contrast with the dearth of any national recommendations or guidelines, in a country that also has extensive coastal areas, archipelagos, numerous marine reserves, and inland waters, and whose topographical and climatological characteristics make it a place that is conducive to the practice of scuba diving.

This work seeks to formulate and propose a guideline that sets out the essential technical, law enforcement, and medical-forensic data to be collected and assessed. It is also to be viewed as a useful, beneficial, and convenient tool for adequately studying deaths that occur while diving.

Multidisciplinary investigation of diving fatalitiesThe judicial autopsy begins as soon as the body is removed. For this reason, and due to both the environment in which these deaths occur and the technical aspects surrounding them, it is essential that the coordinated and multidisciplinary action of technical professionals, police, and forensic doctors is essential, so that each one contributes to the investigation from their area of knowledge, competence, and responsibility. Only when all this information on the event has been gathered should hypotheses be put forth.17

In Spain, we find ourselves in a privileged position, as there is a perfect combination of police units specialised in underwater activities and Institutes of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences (IMLCF for its acronym in Spanish) distributed all over the country, thereby providing for cooperation and fluid communication among the different professionals, regardless of the location in which the fatal diving event takes place.

For their part, these police units have the training and duties, among others, of the Underwater Legal Police and intervene in the search and rescue of the corpse, carry out the technical-police inspection, the technical-analytical examinations of the equipment, and record their findings in the corresponding technical-forensic report. Moreover, the IMLCFs have developed forensic pathology services with qualified personnel specialised in the forensic medical investigation of violent or suspicious deaths. In this sense, our professional expertise has enabled us to adopt an internationally accepted multidisciplinary investigation model that has made it evident that the only way to carry out a highly qualified investigation is through collaborative and complementary work.4,7–9,18

As to the order of intervention, the coroner must have certain technical-police data prior to examining the corpse.8,10 One of these data, if not the most important, is the profile of the dive obtained from the digital autopsy of the dive computer, ideally from the deceased or from the dive buddy. This issue is based on the fact that, among other things, the dive profile contains relevant information concerning the depth reached, dwell time, or ascent speed, all of which are valuable to steer the study and, for instance, to decide on the most appropriate autopsy technique by which to detect arterial gas embolism or choose the most appropriate complementary tests to be carried out. In this sense, it has even been suggested that the presence of teams of diving experts should be mandatory during the autopsy.20

In addition, we must not lose sight of the fact that the cause of death is the last, but not the only link in a chain of events. This is what Denoble et al. established in 2008,5 when they advocated for a study methodology that has now been consolidated and that makes it possible to identify each of the various events that in one way or another intervene in or contribute to the fatal outcome. A sequential analysis of the fatal event is undertaken in order to define the precipitating factor, the incapacitating agent, the disabling injury and, ultimately, the cause of death.

When faced with a death while diving, it is crucial that, insofar as possible, the events that preceded the person's demise be examined so as to determine not only the final cause of death, but also all those factors that were involved beforehand and that in some way precipitated or played a part in the death, making the simple, isolated, and unqualified conclusion of death by immersion unacceptable, a conclusion that is as convenient as it is dangerous.

A diver whose regulator falls out of their mouth because of a seizure will lose their source of gas supply. Such a lack of supply will also occur if all the gas in the cylinder is consumed because the diver has become trapped on the bottom of the body of water. In both cases, the cause of death revealed in the autopsy room will most likely be asphyxia due to drowning and if not for the multidisciplinary approach that we emphasise and the combined action of technical-police and forensic-medical professionals, it would be impossible to ascertain the facts that preceded it and that in one way or another had a bearing on it. Facts, on the other hand, the determination and recording of which are deemed indispensable given their incalculable value when planning and circulating prevention strategies.

Practical guide to data collectionWe propose a guide that provides a simple way of compiling all the technical-police and forensic-medical data that, according to the publications in this field, are regarded as essential to properly direct the study of the causes and circumstances of deaths that have occurred while diving.

It is a user-friendly tool that not only simplifies the task of collecting information, but also contributes to standardising and optimising investigations into deaths of this type which, either because they are rare or because of their highly specific causes, can be approached erroneously or incompletely, resulting in the loss or destruction of pathognomonic signs or in the misinterpretation of post-mortem findings.

Data logThe usual data pertaining to the identification of the legal proceedings and the subject should appear. The deceased's diving qualification and experience expressed in number of dives/year should be indicated. The person's known medical history should also be included, with special emphasis on those conditions that are prevalent in the general population and which, depending on how well controlled they are and their course, are either relative or absolute contraindications to diving, such as asthma,21 diabetes mellitus,22 epilepsy,23 certain psychiatric conditions,23 and cardiovascular disease,24 above all, coronary heart disease. Any prescription drugs22 should also be taken into account.

Police-technical dataThe variables in this section have to do, mainly, with the characteristics of the dive and of the event that will serve as the foundation to inform the subsequent post-mortem examination (Annex 1).

The type of diving may point toward possible circumstances and causes of death such as shallow water, syncope,25 and secondary immersion in free diving or pulmonary barotrauma in the case of diving with compressed air. When available, the buddy system will identify a reference person or persons who can provide information with regard to what happened, how it happened, and whether there was a panic situation. The place and date of both the event and the recovery of the body shall be recorded, given that the time spent in the water, as well as affecting decomposition processes, might account for certain traumatic injuries (rocks, animals, etc.). Specific mention should be made of the time and depth at which the incident took place (descent, bottom, or ascent) and the place where the body was recovered, either on the surface or at the bottom of the water, in which case the depth should be indicated. Similarly, information shall be collected concerning water temperature and environmental conditions, e.g., currents, which could potentially have led to additional physical exertion that could aggravate underlying heart disease.22 In terms of equipment, the record should include whether it is complete, missing, in poor condition, or incorrectly fitted. Making a note of the type of diving suit is of interest above all in relation to the water temperature and its suitability, both for preventing hypothermia and heat stroke. The breathing system should also be logged. The buoyancy system and fins make underwater diving easier and more comfortable, without physical effort. As far as ballast is concerned, it is important to check the amount and the release system.26 In contrast, too much ballast leads to increased physical work, which can result in an unplanned increase in gas consumption27 or decompensate a pre-existing illness.23 In contrast, insufficient weighting at certain depths can result in rapid, uncontrolled ascent. The mask and its proper fit to the face is important for equalisation and why if it gets flooded, it can precipitate submersion.28 Another element to be addressed is the cylinder, its final pressure, and the analysis of its contents.4 A tank with too little pressure can cause panic23 and trigger hasty ascent, while, regardless of contaminants, certain mixtures or gases can be toxic and/or lethal depending on the depth. Knowing whether or not cardio-pulmonary resuscitation manoeuvres have been performed is crucial to correctly interpret certain findings, such as rib fractures or the presence/redistribution of air bubbles.16,29

Whether or not the person was wearing a dive computer and if it is possible to perform a digital autopsy on it, the dive profile will be collected, which will also reveal the maximum depth, dive time, the presence of decompression, and a possible rapid ascent.20

Autopsy techniquesPreliminary assessment of all the data available at this stage will enable us to establish an initial working hypothesis aimed at fully determining whatever the cause of death may have been and which should contemplate submersion as a diagnosis of exclusion, despite the fact that it figures prominently as a diagnosis of exclusion.5

The initial and fundamental approach will revolve around the possible involvement of the biophysical fundamentals that regulate how gases behave in the mechanism of death. A dysbaric condition, i.e., related to pressure changes, should be presumed in the event of a diving death when, regardless of the depth reached during the dive, there is a history of rapid ascent followed by loss of consciousness upon surfacing, suspicion of panic, low gas reserve in the cylinder, overinflated buoyancy system, and/or evidence of subcutaneous emphysema in the cervical–thoracic region on external examination.28 Likewise, it is also judicious to bear this in mind when there are insufficient technical and police elements available so as to venture a hypothesis (Table 2). In fact, in the opinion of Walker et al.,30 any loss of consciousness (even if transitory) within the first 10 min of surfacing after a dive should be presumed to be an arterial gas embolism until proven otherwise. In all these cases, a specific autopsy technique targeting evidence of barotrauma should be proposed.8,16,19

If none of the afore-named criteria are found, the autopsy should proceed accordingly in line with Recommendation no. 993 of the Council of Ministers to Member States regarding the harmonisation of medico-legal autopsies.

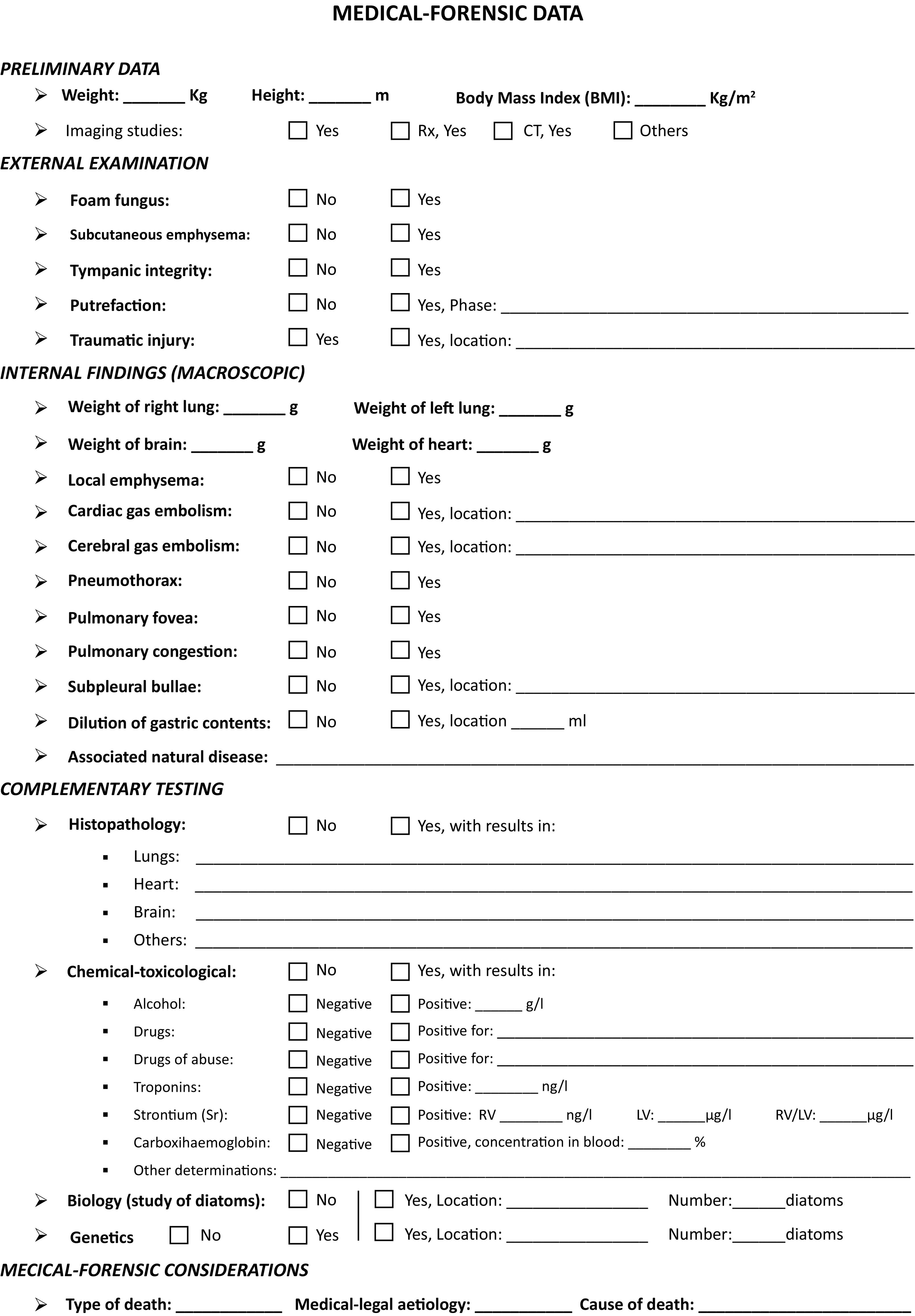

Medical-forensic dataThe variables contemplated in this section are primarily related to the necropsy findings gleaned during the external and internal examination of the autopsy, as well as the results of the complementary tests requested. (Annex 2).

The deceased's height and weight will be collected in order to calculate body mass index. Imaging tests, simple radiology, and, if possible, computed tomography, should be carried out beforehand.7,11 In addition to assessing any signs of putrefaction and those suggestive of traumatic pathology on external examination, in the same way as in any other legal death, any and all additional specific signs related to submersion or pulmonary barotrauma, such as foam fungus or subcutaneous emphysema, respectively, must also be sought. It is also worthwhile that the integrity of the tympanic membrane be evaluated, inasmuch as it is a structure that is vulnerable to changes in pressure.4

The internal examination should include the weight of the viscera in grams, with particular emphasis on those in which signs can be noted that are compatible with the main causes of death whether or not they have to do with the hyperbaric environment, assessing those that are compatible with increased pressure (local emphysema, pneumothorax, subpleural blisters), with submersion (pulmonary fovea, dilution of gastric contents), or with cardiac and/or cerebral gas embolism. We must not lose sight of those signs that are consistent with natural underlying disease (cardiomyopathies, atherosclerosis) which, while perhaps not being sufficient to be causative, do become a contributory factor.

The anatomical study will be completed with the collection of specimens for histopathological, biological, and chemical-toxicological analysis (Order JUS/1291/2010, dated 13 May). At the histopathological level, the most noteworthy findings are cerebral, cardiac, and pulmonary findings, with alveolar septal rupture being the most relevant to confirm barotrauma. Serological or immunological determinations may also be requested in the case of bites16 or studies to assess the vitality of the trauma.12 In terms of chemical-toxicology, the presence of alcohol, drugs of abuse, or medicines that in one way or another may have a modulating effect on the subject's ability to react, must always be ruled out. The determination of strontium levels is reported to be valuable in suspected death by submersion, as is the biological determination of diatoms.16 To rule out natural cardiac disease, troponins can be studied or, depending on the context, genetic analyses can be requested.

In addition to the analysis of the contents of the cylinder, blood carboxyhaemoglobin levels should be carefully examined to rule out carbon monoxide poisoning,4,11,19 a gas that can be present in the breathable gas mixture in excessive proportions due to the use of malfunctioning internal combustion or electric compressors, through negligence or intentionality.

ConclusionsDiving deaths are a challenge for any forensic pathologist, even more so when their infrequent incidence and technical complexity may lead to an overdiagnosis of drowning deaths at the expense of other more specific causes, such as dysbaric disorders.

The proposed guideline, which has been developed on the basis of internationally accepted scientific criteria, consolidates the multidisciplinary approach and constitutes a standardised procedure that contributes to harmonising the working methodology and optimising the analysis of each case.

Moreover, it makes it possible to obtain abundant reliable data, the evaluation of which merits the development of an observatory of diving mortality in Spain which, as a public registry, would systematically compile and analyse them in depth. In this way, it will be possible to understand the casuistry of these deaths, identify risk factors or behaviours, and develop prevention policies aimed at increasing diving safety and decreasing the number of such events.

FundingNone.

Please cite this article as: Fúnez ML, Casadesús JM, Aguirre F, Carrera A, Reina F. Practice guideline for multidisciplinary investigation of diving fatalities. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.remle.2023.12.001.