Psychological autopsy methods often include measures of impulsivity and aggression. The aim is to assess their reliability and validity in a Spanish sample.

MethodsCross-sectional web-based survey was fulfilled by 184 proband and proxy pairs. Data was collected on sociodemographic characteristics, impulsivity through Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), aggression through Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ), and history of suicide ideation. Proxies filled out BIS-11, BPAQ and suicide ideation with the responses they would expect from the probands. Reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between proband and proxies. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the predictive validity of proxy reports in predicting probands’ suicide ideation.

ResultsBivariate analysis showed differences in BPAQ (Median 68 vs. 62; p=0.001), but not in BIS-11 (p>.050). BIS-11 showed good concordance (ICC=0.754; CI 95% 0.671–0.816) and BPAQ acceptable (ICC=0.592; CI 95% 0.442–0.699). In the probands regression model BPAQ predicted suicide ideation (OR 1.038; CI 95% 1.016–1.061) but not BIS-11 (OR 0.991; CI 95% 0.958–1.025). In the proxy-report model BPAQ also predicted probands’ suicide ideation (OR 1.036; CI 95% 1.014–1.058) but not BIS-11 (OR 0.973; CI 95% 0.942–1.004).

ConclusionUsed as proxy-reported assessment tools, BIS-11 showed better reliability than the BPAQ. However, both showed validity in Spanish population and could be included in psychological autopsy protocols.

Proxy-based measures are often used in health sciences research and clinical practice to gather additional information on target population or address potential biases on data collection. Proxies may refer to variables or pieces of information that act similarly to another target variable. For example, a recent study gathered a set of basic sociodemographic data from electronic health records, and successfully used them as a proxy measure of premorbid adjustment in patients with psychotic disorders.1 Proxies may also refer to the very same variable but reported by a different party. In this case, we refer to proxy-reports or third-party assessments. Parental or teacher proxy-reports are an integral part of the assessment of children and adolescents.2 Third-party assessment becomes more relevant the more inaccessible the target population is, as is the case of people with severe cognitive impairment.3 In some scenarios, proxy reports are the only information that can be collected and so it is used in the context recent death, such as posthumous assessment of end-of-life processes4 or suicide.5 However, to ensure that third-party assessment is evidence-based, it is necessary to understand the degree to which subjects and proxies converge in their evaluations and, given the case that they diverge, whether there are systematic biases that could give order to the data obtained or whether biases emerge at random making information unreliable.6

In the context of suicide research, the most used third-party assessment tool is the psychological autopsy. Based on the collection of information through a family member or close relative of the person who has died by suicide, it is recognized as the method of choice for research on deaths by suicide.7 However, the psychological autopsy method entails a series of biases. On the one hand, there are recall biases associated not only with the informant's experience of the death by suicide of their close of kin and the mourning process involved, but also with the time between the death and the interview. On the other hand, poor data collections tools can compromise reliability and validity. These results can be improved by using instruments adapted to the context of the sample and with sound psychometric properties.8

Therefore, research should focus on refining the postmortem assessment, identifying which constructs have optimal reliability, and which are still subject to improvement. Currently, psychological autopsies are being used worldwide and have already showed reliability with respect to clinical diagnosis,9 hopelessness10 or intent to die.11 The increasing interest on the role of impulsivity and aggression in suicide behavior12,13 have led psychological autopsy methods to include scales to evaluate these constructs.14–16 One study carried out in Guangzhou, China, examined the reliability of both impulsivity and aggression scores as reported by close kin informants of suicide attempters and non-suicide attempters, making use of Chinese version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) and Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ). In this study, despite finding statistically significant differences in the scores of specific subscales, suicide attempters and proxies reached agreements between moderate and good.17 Therefore, BIS-11 and BPAQ have promising properties for its inclusion in a psychological autopsy protocol.

Evidence-based assessment goes beyond the standard psychometric properties, encompassing also clinical utility.18 In the case of suicide, this implies accurately identifying facilitating and precipitating factors of suicide. For this reason, in addition to a reliability assessment, we will also test the predictive validity of proxy reports regarding suicide behavior.

The aim of the present study is to confirm the reliability of third-party measures of impulsivity and aggression in a Spanish sample through the validated version of the Barratt Impulsiveness scale (BIS-11) and Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ) in Spanish language. Regarding reliability of proxy-based reports, our hypothesis is that both scales (BIS-11 and BPAQ) will reach an acceptable degree or reliability. An additional aim is to explore the validity of third-party assessments for the prediction of suicide behaviors as reported by first-hand informants.

MethodsStudy design and populationData was collected through a cross-sectional survey. The survey was administered through an online panel. The survey was disseminated among university students of the Universidad de Sevilla and the Universidad de Zaragoza. Surveying methods were instructed in person by specialized personnel. Probands were asked to fulfill the survey about themselves and enter a keyword (to identify the paired subject). This paired subject, or proxy, (first grade family member, partner, or close friend) filled in the BIS-11, BPAQ and suicide behavior items from the perspective of the proband. It was not compulsory for the university students contacted to be the probands, as they were free to change roles with their contact person. Surveying period started on September 2022 and concluded on January the 31st 2023.

The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Comunidad de Aragón (CEICA) in Spain, registry number 17/2022.

ParticipantsA total of 513 participants accessed the survey. After removing invalid cases, the valid sample was comprised of 368 individuals, making up for 184 proband-proxy pairings (Fig. 1).

InstrumentsData was collected on sociodemographic variables (age, gender, civil status, educational level), life history of suicide thought and attempts and the following scales for the measurement of impulsivity and aggression:

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, version 11 (BIS-11): The BIS-11 is a widely used measure for impulsiveness as a trait rather than a state.19 For this study, we used a version in Spanish language, validated in a Spanish sample, which is composed of 30 items instead of the original 37.20 Each item is a 4-point Likert scale assessing the frequency in which the proband engage in impulsive behaviors or cognitions (rarely/never, occasionally, often, always/almost always), each answer having a specific score (0, 1, 3 and 4 respectively, with some items inversed). Total score is obtaining by adding all punctuations without weighting (range 0–120). In addition to the total score, three 10 items subscales can be calculated measuring different aspects of impulsiveness: cognitive, non-planning and motor, with ranges 0–40.

Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ): developed from the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory,21 it is comprised of 29 items, in which the proband indicates her degree of agreement with different statements about herself through 5-point Likert scales (from 1: “I absolutely disagree” to 5: “I absolutely agree”). The inventory has four subscales: verbal aggression, physical aggression, anger and hostility, in addition to the total score.22 For this study we used a version in Spanish language validated in a Spanish sample,23 which has equivalent reliability and factor structure to the original.24

Control of possible biasTo address potential sources of sample bias, the survey included a series of fail-safes questions. A starting question of the survey requested participants to identify themselves in relation to the proband. Possible answers included first degree relatives (“I am their father, mother, brother, sister…”), lasting relationships (“I am their partner, friend, neighbor”) or identifying as the proband (“None, I am fill in this questionnaire on my behalf”). Data crossing between this item and the keyword allowed to identify reliable pairings.

Additionally, control questions were set up between scales of more than 20 items (please select option “x” in this question) to identify and remove any participants answering the survey at random.

Power analysisFor the calculation of the required sample, the program G*Power v.3.1.9.4 was used. An a priori power analysis was performed for the Student's t-test for paired samples for small effect sizes (0.2) and alpha of 0.05 yielded a sample value of 328 individuals (164 pairs).

Statistical analysisThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was carried out to identify the normality of the distributions in the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale and Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire scores and its subscales, to choose a statistical test (parametric or non-parametric) to assess differences in impulsivity and aggression scores distributions between probands and proxies.

Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to evaluate the degree of concordance of the proxy and proband measures. Formula for a 2-way random effects model for absolute agreements ICC was used to estimate ICC and their 95% confident intervals. Both single measures ICCs and average measure ICCs (k=2) were used. The first would identify the reliability of proxies with respect to individual pairings while the second would assess the extent to which the measurements of probands and proxies match each other.

Significance levels of ICC were established following the guidelines proposed by Koo and Li (2016), where values less than 0.5 are indicative of poor reliability, values between 0.5 and 0.75 indicate moderate reliability, values between 0.75 and 0.9 indicate good reliability, and values greater than 0.90 indicate excellent reliability.25

For the predictive validity analysis of third-party assessments, two logistic regression models were performed (the proband model and the proxy model). Both models have the same dependent and control variables, but different independent variables. The dependent variable was the presence of suicide behavior as reported by the proband (either suicide thoughts or attempts). Regression models were carried by enter method in two steps. The first included probands’ gender as a control variable (same in both models). The second step introduced the independents variables, which differed between models. In the proband model, total scores of proband-reported BIS-11 and BPAQ were introduced. In the proxy model, proxy-reports of the total scores of BIS-11 and BPAQ were used instead.

All analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Science SPSS v 26.0.

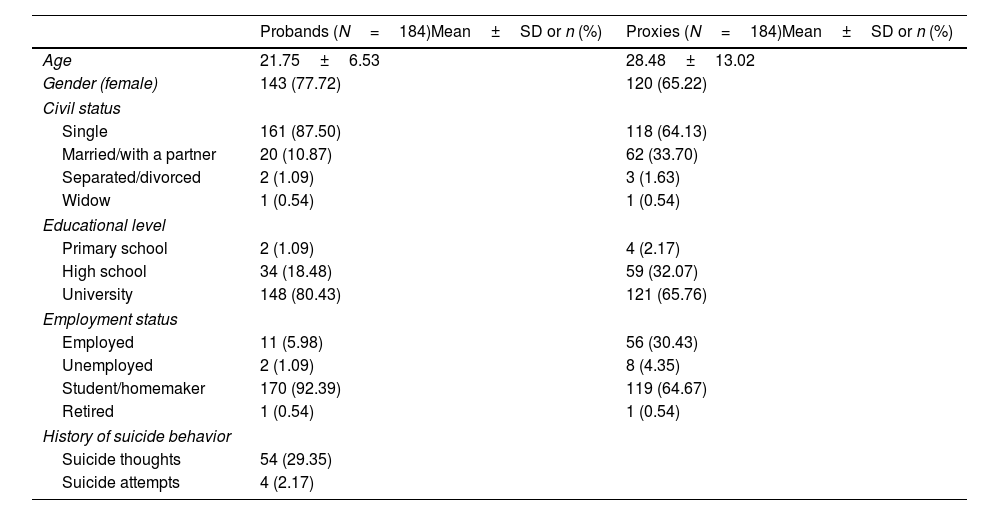

ResultsCharacteristics of the sampleSociodemographic characteristics of both groups are portrayed in Table 1. Proxies’ relations with the probands were as follows: 54 (40.3%) were partners of the probands, 27 (20.2%) were siblings, 26 (19.4%) were their father or mother, 21 (15.7%) were friends or neighbors and six (4.48%) were sons or daughters.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (N=316).

| Probands (N=184)Mean±SD or n (%) | Proxies (N=184)Mean±SD or n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 21.75±6.53 | 28.48±13.02 |

| Gender (female) | 143 (77.72) | 120 (65.22) |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 161 (87.50) | 118 (64.13) |

| Married/with a partner | 20 (10.87) | 62 (33.70) |

| Separated/divorced | 2 (1.09) | 3 (1.63) |

| Widow | 1 (0.54) | 1 (0.54) |

| Educational level | ||

| Primary school | 2 (1.09) | 4 (2.17) |

| High school | 34 (18.48) | 59 (32.07) |

| University | 148 (80.43) | 121 (65.76) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 11 (5.98) | 56 (30.43) |

| Unemployed | 2 (1.09) | 8 (4.35) |

| Student/homemaker | 170 (92.39) | 119 (64.67) |

| Retired | 1 (0.54) | 1 (0.54) |

| History of suicide behavior | ||

| Suicide thoughts | 54 (29.35) | |

| Suicide attempts | 4 (2.17) | |

For each proband score for the BIS-11 and BPAQ, the standard error of measurement was calculated for 95 and 99% confidence intervals.26 These results are depicted in Figs. 2 and 3. For the BIS-11, most of third-party assessments are within the 95% confidence interval and almost all are within the 99% confidence interval. In the case of the BPAQ, less concordance between measures is observed, with a tendency for the proxies to underestimate the scores of the probands. This trend is more apparent regarding probands who self-report higher scores.

Reliability analysisOutcomes of the reliability analysis are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests disproved the normality assumption for the BIS-11, the BPAQ and their respective subscales. Levene's F tests were used to test for heteroscedasticity. The equality of variances was confirmed for both scales and all subscales except BPAQ's physical aggression and rage. Mann–Whitney tests were carried out to check differences in the impulsivity and aggression scores between probands and proxies.

Differences in BIS-11 and BPAQ and their subscales distributions between probands and proxies (N=384).

| Probands(Med [Q1–Q3]) | Proxies(Med [Q1–Q3]) | p-Value | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS-11 | ||||

| Cognitive | 14 [11–17] | 14 [12–17] | 0.418 | – |

| Non-planning | 20 [17–24] | 20 [16–23] | 0.433 | – |

| Motor | 18 [15–24] | 20 [16–24] | 0.139 | – |

| Total | 54 [46.5–60] | 54 [48.5–61] | 0.399 | – |

| BPAQ | ||||

| Physical aggression | 15 [13–19] | 13 [10–17] | <0.001 | 0.264 |

| Verbal aggression | 14 [11–17] | 14 [10–17] | 0.929 | – |

| Rage | 20 [17–23] | 17 [14–22] | <0.001 | 0.375 |

| Hostility | 19 [15–24] | 17 [13.5–22] | 0.002 | 0.319 |

| Total | 68 [59–79.5] | 62 [53–77] | 0.001 | 0.326 |

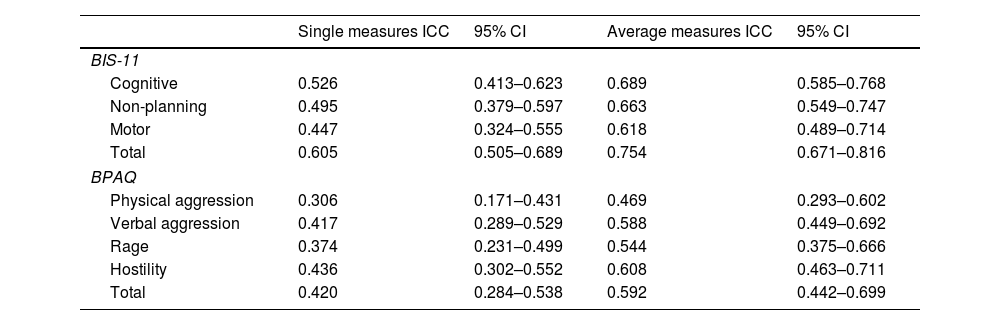

Intraclass correlation coefficients between proband and proxy reports (N=384).

| Single measures ICC | 95% CI | Average measures ICC | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS-11 | ||||

| Cognitive | 0.526 | 0.413–0.623 | 0.689 | 0.585–0.768 |

| Non-planning | 0.495 | 0.379–0.597 | 0.663 | 0.549–0.747 |

| Motor | 0.447 | 0.324–0.555 | 0.618 | 0.489–0.714 |

| Total | 0.605 | 0.505–0.689 | 0.754 | 0.671–0.816 |

| BPAQ | ||||

| Physical aggression | 0.306 | 0.171–0.431 | 0.469 | 0.293–0.602 |

| Verbal aggression | 0.417 | 0.289–0.529 | 0.588 | 0.449–0.692 |

| Rage | 0.374 | 0.231–0.499 | 0.544 | 0.375–0.666 |

| Hostility | 0.436 | 0.302–0.552 | 0.608 | 0.463–0.711 |

| Total | 0.420 | 0.284–0.538 | 0.592 | 0.442–0.699 |

Results of the Mann–Whitney test showed no statistically significant differences for impulsivity scales (all p>.05). However, all subscales of the BPAQ and the total score showed statistically significant differences between probands and proxies (all p<.05), except for verbal aggression subscale (p=0.620). Cohen's D was calculated to assess size effect, which appeared to be low (Table 2).

With respect to correlation measures, the degree of concordance reached by the single measures ICC for the total BIS-11 score was moderate (ICC=0.605). Its subscales showed slightly lower values, with cognitive impulsivity reaching moderate levels of concordance (ICC=0.526), non-planning impulsivity showing a value just below the cut-off to be considered moderate (ICC=0.495) and motor impulsivity not reaching a moderate level a reliability (ICC=0.447). As for average measures ICC, the highest degree of concordance was achieved by the total BIS-11 score showing moderate concordance (ICC=0.754). All subscales performed similarly when examining average measures ICC.

BPAQ scores showed a lower degree of concordance to that of the BIS-11. For the single ICC, no component obtained a moderate concordance level. However, when looking at the average measures ICC all scales obtained a moderate level of concordance except the physical aggression subscale (ICC=0.469). The greater concordance was reached by the hostility subscale (ICC=0.608), followed by the total score (ICC=0.592), verbal aggression (ICC=0.588) and finally the rage subscale (ICC=0.544; Table 3).

Validity analysisResults for the logistic regression for utility analysis are shown in Table 4. In the proband model, BPAQ total score emerged as associated factor for the presence of suicide behavior in probands, but not the BIS-11 score. The same phenomenon occurs in its twin model, in which proxy BPAQ score it's found to be associated but not proxy-reported impulsivity.

Logistic regression models for the prediction of suicide behavior (N=184.

| Proband model | Proxy model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | CI 95% | p-Value | OR | CI 95% | p-Value |

| Constant | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.039 | 0.010 | ||

| Gender (female) | 2.731 | 1.091–6.840 | 0.032 | 2.340 | 0.937–5.843 | 0.069 |

| BIS-11 total score | 0.991 | 0.958–1.025 | 0.586 | 0.973 | 0.942–1.004 | 0.087 |

| BPAQ total score | 1.038 | 1.016–1.061 | 0.001 | 1.036 | 1.014–1.058 | 0.001 |

Enter method. First step: Proband gender. Second step BIS-11 total score and BPAQ total score, as reported by probands and proxies in their respective models. Dependent variable: Proband suicide behavior.

The present study provides relevant data on the reliability and validity of third-party assessment of impulsivity and aggression. Proband and proxy reports of BIS-11 and BPAQ scores reach a moderate level of concordance, indicating sufficient reliability, with some limitations. Specifically, we found a trend in proxies of underestimating proband's aggression. Moreover, logistic regression analysis for the prediction of suicide behavior by third-party reports shows equivalent degree of validity to that of first-hand probands.

Regarding impulsivity, we found no differences between proband and proxy distributions of BIS-11 scores, neither for the total nor for any of its subscales. When examining the averages ICCs, they achieve moderate reliability, reflecting medium agreement between probands and proxies. Except for the motor subscale, all the BIS-11 subscales plus the total score reach moderate concordance levels.

In the case of aggression, probands reported systematically higher aggression than proxies in all BPAQ subscales except in the verbal aggression scale. Probably, the lack of differences in verbal aggression is because this subscale is more closely related to social interaction with others in general and with the proxies in particular. This finding is surprising, as the response bias regarding aggression has been reported to occur the other way around: with people underestimating its own aggression when compared with third party reports.27 This may be due to a sample selection bias. The majority of probands were medical students, a group with high responsibility, prone to guilt and harsh in their self-evaluation.28 Another possibility is that proxies may have incurred in a response bias, with a tendency to score low on aggression items. This has not been the case with those forms of aggression that are socially accepted, identified in items such as “I tell my friends openly when I disagree with them”, “I flare up quickly but get over it quickly” or “I often find myself disagreeing with people”. It is not clear that this bias can occur in the context of a psychological autopsy, where the individual being reported on is already deceased and cannot be hurt by an opinion about his or her behavior.

Interestingly, in the study carried out in China, mean differences were the opposite: it was the impulsivity scores that showed statistical differences, with probands undervaluing instead of over-rating their scores.17 Differences between the Spanish and Chinese studies may could be related to the way those different cultures express their emotions and cope with conflict.29

Overall, in terms of the degree of agreement between groups, we see that third-party assessment achieve a low degree of reliability in predicting the exact test score of their respective proband pairing as assessed by the single measures ICCs. However, this may not necessarily reflect poor reliability of proxy reports. Probands are known to be subject to several bias on their self-report, such as social desirability or recall bias, that could potentially affect assessment.30 A third-party could manage to obtain more reliable information in some scenarios. Of course, proxies are subject to bias of other kind (attributional or others) that could also affect their evaluation. After all, neither probands nor proxies can ensure absolute reliability over parameters such as personality, and for this reason average measures ICCs may be the most appropriate assessment for concordance. Even so, there are ways in which reliability of proxy measures could be improved, such as involving several proxies in the assessment process.31 However, further research has shown that adding further informants do not necessarily enhance validity of third-party assessments significantly.32

An important aspect of this study is that, even if the reliability of proxies has room for improvement, it is enough to ensure the predictive validity of third-party assessments. The behavior of both impulsivity and aggression measures in the twin regression models is identical, with close odd ratios and similar confidence intervals. This mean that proxy-reports of impulsivity and aggression as measured by the BIS-11 and BPAQ have as much predictive value over suicide ideation that the same scores reported by first-hand probands. This has important implications for the systematic assessment of these two factors through friends and family. Moreover, it builds foundation for psychological autopsy studies aiming to measure impulsivity and aggression in their protocols.

Strengths and limitationsThis study has made contributions to the reliability and predictive validity of on the proxy-based assessment of impulsivity and aggression. These data will help to interpret ongoing research on suicidology and suicide prevention while opening the door to the use of proxy reports of impulsivity and aggression to other research areas. To our knowledge, this is the first study carried out in Spain assessing the reliability and validity of the assessment of impulsivity and aggression as reported by proxies. Moreover, is the first attempt in Spanish to validate in living persons instruments for their introduction in a psychological autopsy procedure, a cornerstone for the effective utilization of this method. It has made use of scales widely used in English speaking countries while having been specifically validated in Spanish language. However, this study is not without limitations.

First, the study was conducted on non-clinical sample of university students and their close relatives, where the proportion of suicide attempts was below 3%. This is not an accurate reflection, in terms of representation, of the characteristics that can be found in a study of death by suicide. Alas, the transfer of these findings to the study of lethal suicidal behavior is limited. Second, suicide-related outcomes were assessed using a single item instead of validated instruments, nor it was confirmed by expert clinician assessment. Third, the study could benefit for a greater sample as interclass correlation coefficients are subject to variations related to sample size.

The ideal conditions for achieving the objectives of this study would be (1) to recruit a large sample with a significant proportion of people showing suicidal behavior and, (2) to rely on the use of validated scales for suicidal behavior (such as the Beck's Suicidal Intention Scale or other), to be completed by both patients and key informants (proxies). Unfortunately, carrying out a study of this scale was beyond the authors’ reach.

ConclusionsBoth the Barratt Impulsivity Scale and the Buss–Perry Aggression Questionnaire in their Spanish abbreviated versions would be suitable instruments to use as a proxy-based assessment tool in Spanish speakers in terms of predictive validity. Additionally, the BIS-11 shows moderate reliability. The BPAQ could achieve good reliability rates if the tendency of proxies to underestimate proband's aggression is controlled. This information should be considered to correctly interpret studies based on proxy reports.

Ethical disclosureAll patient signed opt-in informed consent prior to their participation in the survey. The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Comunidad de Aragón (CEICA) in Spain, registry number 17/2022.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FundingSergio Sanz-Gomez work is supported by the VI-PPITUS.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank all participants who took part in the survey, as well as Andrea Escolano, Leonor González, Julia Gracia, Rosa Moret, María Isabel Perea-González and Noemí Sanmiguel who supported the dissemination of the survey.