Information communication technology (ICT) mediated innovation–adoption–implementation is one of the prime factors in the development of a nation. Its enhancement can improve the productive capacity of developing countries. Though developing countries import much of their technology from abroad, ultimate success depends on the technological efforts and capabilities of individuals and organizations. But lack of capacity, technological know-how, training and experience limit developing countries in both utilizing the full potential of those imported technologies and developing an indigenous technology at a later stage. It now seems important to know and understand the functions, dynamics and critical success factors of the innovation–adoption–implementation of these ICT-led initiatives at three different interconnected social levels (i.e. macro, meso and micro) that we have conceptualized. The purpose of this study is to illustrate the innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D project in rural Bangladesh. This study showed that government, private organization, and NGO have initiated different ICT4D project nationwide, especially for rural people in Bangladesh.

Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) is a range of activity which reflects how electronic technologies can be used towards socio-economic development of developing communities worldwide (Donner & Toyama, 2009). It is an initiative aimed at bridging the ‘digital divide’ and aiding economic development by ensuring equitable access to up-to-date communications technologies (van Reijswoud, 2009; Zinnbauer, 2007). It assists underprivileged populations (i.e. People in rural areas) anywhere in the world, but it is usually associated with applications in developing countries (Karanasios, 2013). Since the eighteen-century, ICT supported initiatives in developing countries, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia, have attempted to address a range of national developmental issues including social, economic, technical, educational, cultural, rural and community disadvantage through a range of pilot projects (telecentre, multipurpose community access centre, information kiosks to name a few).

Like other developing countries, Bangladesh has also initiated a range of ICT4D projects in rural and remote communities (micro level) through the direct intervention of international donor, international developmental agencies, NGOs, community groups, and private initiators (meso level). With a population of 160 million, 74% of the people live in rural areas and depend on agriculture. The government is aiming to transform the present ICT infrastructure with a vision (Vision 2021) to create “Digital Bangladesh”. Aiming to build technology enabled country, the government has already implemented ICT in all phases of government agencies and tried to enlarge the beneficiary groups with the help of private sectors (Karim, 2010).

However, at present, people in rural areas of Bangladesh have limited access to ICT and Internet. It is noteworthy that when the Government declared Information communication technology (ICT) a ‘thrust’ sector in the last decade, many young Bangladeshi men and women from abroad with sufficient education, knowledge, skills and marketing experience rushed back to Bangladesh (ITU, 2004); but low bandwidth and the high cost of Internet access prevented them from establishing an ICT-enabled business network there. Very little work to date has drawn from the innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D—linking concepts in development studies to this research domain. The purpose of this study is to illustrate the innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D project in rural Bangladesh.

2An overview of ICT profile in BangladeshBangladesh has a total cellular subscription of 120.4 million. As per the population of Bangladesh it has a population to cellular user ratio of 72–100. Bangladesh is the 12th largest country in terms of mobile phone use. Bangladesh has an internet user of 11.4 million. It constructs the 6.9% of the total population of Bangladesh. It means Bangladesh is the 42nd largest country in terms of internet using in the world (CIA, 2015). Bangladesh has a SEA-ME-WE-4 fibre optics providing Bangladesh link to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia; satellite earth stations – 6; international radiotelephone communications and landline service to neighbouring countries.

The earning from outsourcing IT jobs has increased by 56% in 2013, said sources in the Bangladesh Association for Software and Information Services (BASIS). In the 2011–12 fiscal year, the earning was USD 70.6 million, while it was USD 46.35 million in the 2010–11 fiscal year, referring to the latest available data of the Export Promotion Bureau (EPB). According to BASIS officials, at present there are more than 500 software companies in the country. Of these, about 178 are doing outsourcing jobs (Digital World, 2016). In 2002, Bangladesh identified ICT as a “thrust sector” as it represents potential for quick wins in reforms, job creation, industry growth, improving governance and facilitating inclusion, and it has high spillover effects to other sectors. Today, in Bangladesh, the overall IT sector (excluding telecoms) is small, valued at $300 million, with IT/ITES claiming 39% ($117 million) of that value. The overall IT/ITES industry has enjoyed a high growth rate of 40% over the last five (5) years and this trend is expected to continue.

3Innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT interventionThe effectiveness of ICT interventions in developing countries depends on the integration and possible change or reorganization at three different levels within the national context. These three interconnected levels are macro (national development strategic), meso (organization) and micro level (individual/community) (Avgerou, 2001; Heeks & Kenny, 2002; Heeks, 2002). Pilot projects in developing countries are typically guided and designed at the macro level (national strategic), adopted at the meso level (organization), implemented at the micro level (individual/community), and are exclusively dependent on the interest and fund from the international development agencies. This can be summarized in Fig. 1.

3.1Macro levelICT as a catalyst can contribute to a particular development sector if it combines with an appropriate national development strategy. For instance, a strategic development programme in developing countries integrates the alleviation of poverty, education, human skills building and the creation of a social environment that is conducive to the provision of universal access to basic welfare systems. This implies that ICT interventions in developing countries should address one or more of the above issues, be linked to the national development programmes of the corresponding country and applied appropriately (Macome, 2002; Markus, 2000; Sawyer, 2002; Soeftestad & Sein, 2003). Moreover, it is also important to modify the contemporary national strategy or policy for realizing the potential benefit of ICT in national development. For instance,1 Bangladesh, a primarily agriculture-based economy, has a public sector agricultural technology system which is obsolete and inadequate to meet the new challenges of market-driven commercial agriculture (lacking adequate access to environmentally friendly seeds, fertilizer, post-harvest management systems and so on). A well-resourced and responsive agriculture technology system is a priority for meeting the current and future needs in this sector. Therefore, a comprehensive agricultural technology policy or a fresh extension of existing agricultural technology policy will be a critical challenge to be addressed.

3.2Meso (organization) and micro level (individual/community)Apart from national strategic level, successful adaptation and implementation of ICTs depend on the role of organization's to satisfy the interest of community/individual people. Madon (2000) emphasizes the adaptation of the internet and possible organization change within socio-economic development strategies for developing countries. Such development is only possible if the change focuses the interest of local communities within which the ICT application is implemented. Harris (2002, 2004) emphasizes the importance of analyzing the ‘demand’ of the local context in community/individual level for the successful adaptation and implementation of ICT projects in developing countries. According to Harris (2002, 2004), a top down supply-driven approach is useful for deploying the technology once the ‘demand’ of the local context is identified. The government of Bangladesh has increasingly utilized the ICT4D projects as a means of the strategic provision of delivering public goods and services. The present government has expressed its firm commitment to transform the “contextless” nature of public administration to a citizen-friendly, accountable, and transparent government by implementing the different ICT4D project in its rural and regional areas (Bhuiyan, 2011).

4Innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D project in rural BangladeshGovernment of Bangladesh has taken a number of initiatives to introducing various ICT4D project in its rural and regional areas. Union Information and Service Centre (UISC) is one of those initiatives which are expected to bring the opportunity for rural underprivileged communities to better access to ICT (Hoque & Sorwar, 2014). Mobile phone companies, private organization, and NGO have also initiated different ICT4D project nationwide, especially for rural people in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) introduced ICT4D project, known as Gonokendra Pathagar (People's Centre Library),2 into rural areas in Bangladesh. Here is some index and facts that can be taken into consideration (CIA, 2015) (Table 1).

In 1995, the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC)—one of the largest Non-Government Organisations (NGOs), with multi-faceted development interventions targeting poverty alleviation and empowerment of the poor in Bangladesh—introduced community-based village libraries, known as Gonokendra Pathagar, into rural areas, under its Education Program (EP) and Continuing Education Programme (CEP). The primary objectives of this community-based village libraries initiative were

- •

to create access to printed reading materials and other educational media to rural neo-literate, semi-literate and literate communities, and

- •

to stimulate interest in acquiring information and encountering new ideas.

From 1995, BRAC focused on printed library resources through Gonokendra Pathagar Since then it has introduced new ICT programmes, and renamed the overall intervention simply ‘Gonokendra’.

4.2Formation of GonokendrasGonokendras are mainly funded by joint financial contribution from both BRAC and the community involved. Before establishing a Gonokendra in a village, at first, the authority completes a field study, which includes a needs assessment and community involvement. Community involvement is considered as a core element. BRAC investigates the demand for a Gonokendra, considering sites that are suitable, convenient and have a reasonable number of people, markets, post offices, and a union parishad (local government office). They prefer to establish Gonokendras in standalone buildings or in close proximity to the secondary high school/college in the village. If there is a positive response from the local community, BRAC sends an offer letter to the school's management committee, the headmaster or a nominee from the community, regarding establishing a Gonokendra. The rural community provides a room of 400–500 square feet for the library premises, free of cost, and must sign up at least 200–300 people—these will include donor members, lifelong members, general members and student members—with a minimum of Bangladesh Taka (BDT) 50,000. Membership categories have varying fees.

As soon as the community approached raises this membership fund, BRAC provides a matching grant of BDT50000 to create a reserve fund for the Gonokendra. While there is no maximum target limit for membership numbers or amount of funds to be raised for any Gonokendra, BRAC's financial contribution will not be more than BDT100000. The total amount is then deposited into a fixed term account in the name of a trustee board in a recognized financial institution. The Gonokendra's recurring expenses, such as the librarian's salary, electricity and stationery are paid from the monthly interest on this investment. BRAC also provides 1000 books, necessary furniture, training and supervisory support for each Gonokendra; as well as training facilities for the librarian and trustee member at BRAC's TARC (Training and Resources Centre). The training session includes understanding the basic operations of the Gonokendra and familiarization with the librarian's role and responsibilities.

Each Gonokendra is managed by a committee of 7–9 local members and one committee member from BRAC. Committee meetings are held at least once a month, with the intention that the Gonokendra will become financially sustainable within 2–3 years. To encourage people to become familiar with technology and its various applications, BRAC initiated an ICT programme as part of the Gonokendra initiative. The objectives of the ICT programme are:

- •

to increase familiarity with computers amongst rural communities,

- •

to promote computer training in rural areas,

- •

to create access to ICT education (CDs covering basic academic learning, health, legal and environmental issues),

- •

to expose rural people to new and modern technology (i.e., computers) and develop skills amongst the librarians, children, adolescents, youth, and other villagers to face future challenges,

- •

to give special attention to poor women, girls and disabled villagers (BRAC fully or partially subsidizes training fees for these groups).

Some of the ICT services at Gonokendras are described below.

4.3.1Computer training courseComputer training is one of the major components of the ICT programme offered by Gonokendra. It consists of different computer courses for various age groups in rural areas, depending on the duration and capacity of the trainer who is the Gonokendra's librarian—each librarian has the role of trainer for all computer courses offered in her Gonokendra. The librarians are trained at BRAC's TARC in the city, which is responsible for drawing up different computer training sessions for them. TARC has designed, initially, two training blocks and instruction manuals for the librarians, all of whom must follow the same instruction manuals for computer training at their Gonokendras. The first block of this training includes 12 days’ basic computer training—introduction to computer, drawing/painting, typing, and an introduction to Microsoft's ‘Word’ package—followed by a three-month placement at a Gonokendra. The second block of training consists of 30 days of advanced computer training—basic Microsoft ‘Word’ and ‘Excel’ packages—followed by another placement, of six months. In this second block, the librarian also gets an opportunity to share her work experiences with the TARC staff. Following are the four different computer courses offer by Gonokendra, each course consisting of one-hour session per day:

- •

ICT for children aged 7–10: this package costs BDT150 for 21 days. The children are given lessons in basic computer operation and drawing. Disabled and poor children receive special rates to take this course.

- •

ICT for school students aged 11–15: BRAC recently started this ‘Student package’ programme for high school students which costs BDT100 for a one-month course. A student receives basic computer operation knowledge, some knowledge about MS ‘Word’ and how to use CDs.

- •

ICT for Youth (general package): this is mainly offered to the educated young with the aim of building their ICT skills and providing improved scope in the job market. It costs BDT 500 for a one-month course. The programme, offered over three months, includes basic computer operation, MS ‘Word’, MS ‘Excel’, MS ‘PowerPoint’ and multimedia.

- •

ICT for women, the poor and disabled people: in rural areas women, the poor and disabled are not able to access basic education. The aim of this package is to motivate and encourage these socially and financially isolated groups by providing access to basic computer operations training sessions free of cost.

Each Gonokendra has a set of 15–20 compact disks (CDs): most have been produced in the local language. The participants watch these CDs in a group organized by the librarian/trainer once a week. The CDs contain information related to different educational and social awareness issues, such as:

- •

General knowledge;

- •

Health information—dealing with diarrhoea, drinking safe water, using sanitary latrines in the household, child and pregnant mother healthcare, basic cleanliness issues, AIDS, etc.;

- •

Legal information—early marriage, dowry, women's rights, legal assistance, etc.; and

- •

Environmental issues—e.g., using organic fertilizers.

This provides a valuable information bank for the villagers. Table 2 provides a list of CDs with their contents in demonstration of this multimedia-based information dissemination programme.

List of CDs/contents.

| Name | Key area | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Amader Computer (Our Computer) | Basic knowledge and operation of computers | Developed for children, with cartoon-based lessons. The children learn about the computer, its uses, functions, etc. |

| Health Tips | • Different diseases, cures, and health-related issues • Pregnant mother health care and child rearing | Slideshow presentation of health-related issues, with a brief description of best health practices. |

| Bangladesh Bissokosh (Encyclopaedia of Bangladesh) | Overview of Bangladesh including maps, history, culture, etc. | Contains the history of what is now Bangladesh from 1757; with details about the country, its culture, the biography of successful Bangladeshis, songs, photographs and video clips about the country. |

| Talking Dictionary | English to Bangla/Bangla to English. | In the local language; especially for the young. |

| Virtual Science | General maths, physics, chemistry, biology and geography | Academic learning, containing general science. Different functions, with audio and visual lessons for proper clarification of the subject matter. Has an exam section. |

| Meena Cartoon | • Basic health practice • Environmental issues • Legal issues (e.g., early marriage, human rights and dowry) | A popular cartoon among people of all ages. Meena is about a rural girl who learns social/educational/health/legal issues from the school and applies them to her world. |

| Chelebella-Char (Childhood-4) | Details about the world, the planets and comets | Contains information on the evaluation of the planets and comets. The voice-enabled presentation makes this CD particularly attractive to viewers. |

| Bangla typing tutor | Instructions and exercises | A tutorial on typing Bangla (local language). It has instructions, practical exercises and a grammar check tool. |

| Jeeon (Rural livelihood information) | Agriculture and non-agricultural practices, awareness of health, the environment and legal aid | Contains information on health, society, legal matters, the environment and so on. An audio-visual slide presentation that includes video clips. |

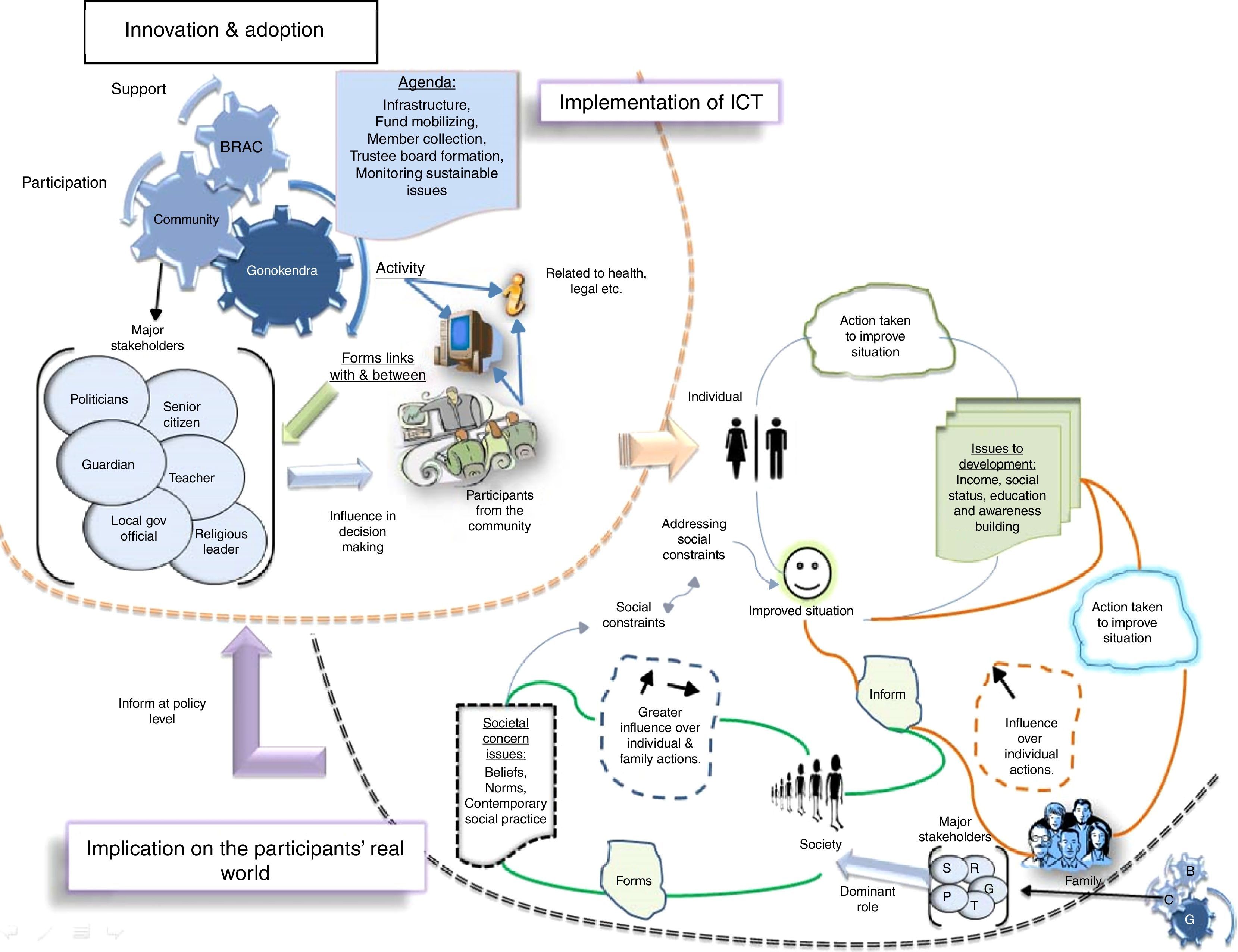

In Fig. 2 we present an illustration from Gonokendra Project at the micro level. We conceptualize development as an ‘improved situation’ through the interaction and influence of individual, family group and society at the community level.

Fig. 2 is in two major parts: the first refers to the innovation, adoption and implementation of ICT in rural communities, in brief, the ICT intervention is implemented through a collaborative efforts (innovation and adoption) between BRAC, a local NGO and the community—which is the owner of the project where the people actively participate in the operation. Two major activities of the ICT intervention—computer training courses and multimedia sessions—form the focal study of this research. This indicates social innovation which refers to new strategies, concepts, ideas and organizations that meet social needs of all kinds—from working conditions and education to community development and health—and that extend and strengthen civil society. With the collaboration of different stakeholders of society such as government organizations, non-government organizations, social innovation design can turn into a significant summit in which the development will be optimized (Brown & Wyatt, 2015).

The second part shows the implications of the ICT programme for the participants’ world, in terms of being conducive to their economic and social development. ICT-led developmental impact is described as ‘issues of development’ in the illustration.

5Future challengesIn this article, we illustrate the innovation–adoption–implementation issues of Gonokendra to a certain community. This can be further understood by considering two key major issues/factors: ICT innovation and its social effects, and the relationship between IS/ICT and organizational change for understanding the adoption and implementation.

5.1Diffusion of Innovation and transfer of ICT innovationResearch into diffusion of innovation, focusing on the organizational level, demands certain provisions before adopting technology in a society (Banuri, 2003). In Gonokendra case, it is essential to have a PC before accessing the Internet. Unfortunately, this technological driven model by Roger might not work properly in a developing country like Bangladesh, “where infrastructure cannot expand at a rate faster than public sector investment program” (Banuri, 2003). Technology is the central theme of the research in diffusion of innovation, with lesser emphasis on the social influences of an innovation.

Time is an important element of diffusion of innovation research (Rogers, 1995). The traditional diffusion study assumes that innovation is invariable over time which can be problematic in the context of today's rapidly changing technological environment. In some cases, ICT pilot projects for development suggest to wait an unreasonable amount of time in order to be able to share in the benefits of development.

5.2IS/ICT and organizational changeThe role of information systems in organizational change was recognized a long time ago. Since 1980s, researchers have been attempting to understand the mutual interconnection between information systems and organizational change from the strategic business and contextual points of view. Such attempts imply the adoption and implementation of technology within the changing business environment. In Gonokendra case, it is important to investigate internal and external factors that affect organizational change and how actors (people, senior management) can act purposefully in managing change. The study of organizational change for the innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT programme can be done within an independent context surrounded by social actors. This approach studies the interaction of multi-level structures, systems within which the ICT is implanted as well as the process of change over time.

5.3IS/ICT and empowermentICT can address numerous issues including empowerment of citizens. This empowering idea is repeated throughout the ICT policy document in different countries in all over the world. The information society, which is the centre of attention of the ICT, is said to be a society where “citizens are empowered. Although ICTs can be important resources for citizens empowerment, it depends on which citizen and which context. In Gonokendra case, it is important to investigate empowerment factors that affect people in society.

6ConclusionThis paper successfully depicts the innovation–adoption–implementation scenario of ICT4D project in Bangladesh in terms of three social levels: macro, meso and micro. In terms of the different projects adopted by Bangladesh government for the vision of Digital Bangladesh, this research has presented the pertinent functions, dynamics and critical success factors of innovation–adoption–implementation. Though this research is conducted on a certain community, it is worth to conclude that this research has been able to demonstrate the critical claims considering innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D projects of Bangladesh. A further research can extend the current study to different communities in Bangladesh. Future research could investigate the innovation–adoption–implementation of ICT4D projects of Bangladesh initiated by government, NGO and private organization.