The way an employee behaves in his work can be influenced by the organisational and professional commitment. Nurses are professionals who are guided by organisational and professional goals and values. Among nurses, professional commitment may be an important antecedent of organisational citizenship behaviours.

The study shows how organisational and professional commitment is related with nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviours. Data from a sample of 420 nurses working in two hospitals – the Hospital of St. Marcos, Braga and the Hospital Centre of Alto Ave, Guimarães and Fafe units were collected. The main findings are as follows: (a) organisational commitment and professional commitment contribute to the explanation of nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviours, (b) affective organisational commitment, continuance organisational commitment – personal sacrifice, affective professional commitment and continuance professional commitment explain 28.6% of variance of organisational citizenship behaviours.

The research of organisational citizenship behaviours has proven that this class of behaviours has contributed for the increase of the organisational effectiveness and for the improvement of the organisational environment and the relationships in work context (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Paine, 1999; Podsakoff & Mackenzie, 1997; Podsakoff, Whiting, & Podsakoff, 2009; Rego & Pina e Cunha, 2006). The organisations hardly would survive if they counted only on the contribution of the employees¿ tasks that are obligated to carry out. In a competitive context marked by the turbulence of the markets, while demanding fast, innovative and flexible answers to meet the requirements of the market, it is necessary that the employees cooperate among themselves, be conscientious in the fulfilment of their professional duties and defend and protect the organisation (Rego & Cunha, 2006). The hospital context is no exception to this reality.

The literature revision shows scarce specific and simultaneous studies related on the relation between foci and dimensions of commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours. Most of the research attribute to personality, leadership and satisfaction the leading role in the explanation of the organisational citizenship behaviours (Bateman & Organ, 1983; Diefendorff, Brown, Kamin, & Lord, 2002). Less attention has been paid to the relation of the commitment with the organisational citizenship behaviours.

The prevailing paradigm in management literature has neglected the effect of professional commitment on organisational citizenship behaviours. Cohen (1999), based on a sample of nurses, found a negative relationship between professional commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours. Individuals may adopt behaviours that are important to their profession and their professional development, but not necessarily to the organisation, as is the case of organisational citizenship behaviours (Cohen & Kol, 2004). Nursing is a profession. Truly important for the development of this profession was the emergence of the Code of Practice for Portuguese Nurses (1996) and the Code of Ethics for Nurses (1998), which dictate the principles of this profession. These normative tools refer the nurses’ duty to help other colleagues and maintain a high standard of personal conduct in order to dignify the profession. These behaviours appear to be coincident with the behaviours that the literature refers as organisational citizenship behaviours. In addition, the hospital is a professional organisation, so the values and goals that it advocates have a higher chance of being in line with the values and goals of the nursing profession. Those appear to be reasons to believe that both organisational commitment and professional commitment may explain the nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviours.

The aim of this research is to analyse the relationship between organisational commitment and professional commitment, and their dimensions, and organisational citizenship behaviours in a sample of Portuguese nurses.

This study analyses two foci of commitment: the organisation and the profession, based on a multidimensional perspective. The interest in using a multidimensional approach lies in the fact that each dimension of commitment can explain in a different way organisational citizenship behaviours. Few studies have examined the various foci of commitment, and their dimensions, and their influence on explaining organisational citizenship behaviours (Randall & Cote, 1991).

The study was conducted in the Portuguese population. The empirical evidence outside the American context is still scarce (Chen & Francesco, 2003; Cohen, 2006; Gautam, Van Dick, Wagner, Upadhyay, & Davis, 2005; Kuehn & Al-Busaidi, 2002). Although not specifically addressing the relationship between organisational commitment and professional commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours, Rego and Cunha (2010) have studied some antecedents of organisational citizenship behaviours, such as organisational justice. However, the authors did not study nurses samples.

This paper is organized as follows. We start by carrying out a review of studies addressing the relationship between commitments and organisational citizenship behaviours and draw the hypotheses. Then we show the method and the sample and measures used in this study. Finally, we present and discuss the results and we present some limitations and future avenues for research of this study.

1Organisational and professional commitments and organisational citizenship behavioursIn their review of the organisational commitment literature, Meyer and Allen (1991) identified three distinct themes in the definition of commitment: commitment as an affective attachment to the organisation, commitment as a perceived cost associated with leaving the organisation, and commitment as an obligation to remain. Employees with a strong affective commitment remain with the organisation because they want to, those with a strong continuance commitment remain because they need to, and those a strong normative commitment remain because they feel they ought to do so.

Allen and Meyer (1990) and Meyer and Allen (1991, 1997) argued that it is more appropriate to consider affective, continuance and normative commitments as components of organisational commitment, and not as different types of organisational commitment, because the relationship of the employees with organisation may reflect varying degrees of all types of commitment. Allen and Meyer (1990) and Meyer and Allen (1997) have taken the multidimensional nature of organisational commitment. They designed measures for the dimensions of commitment: the scale of affective commitment, the scale of normative commitment and the scale of continuance commitment. Meyer and Allen (1997) found that their model was the one to date that had greater empirical validation. Hackett, Bycio, and Hausdorf (1994) found support for the model of the three components of Allen and Meyer (1990). Meyer and Allen (1997) emphasized the superiority of their model, justifying it with the fact that their theoretical model incorporating the results of a large number of previous studies and use other measures that others developed to test their models. The empirical validation of their model has been extended to other countries (see for example, Cheng & Stockdale, 2003; Gautam, Van Dick, & Wagner, 2001), which only strengthens the tridimensional vision of commitment.

Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993) presented the multidimensional perspective of professional commitment (affective, normative and continuance dimensions) and extended the tridimensional model of organisational commitment to the profession. Employees with a strong affective commitment remain with the profession because they want to, those with a strong continuance commitment remain because they need to, and those a strong normative commitment remain because they feel they ought to do so. The model validity was confirmed by Irving, Coleman, and Cooper (1997) in a sample of various professions.

Organisation citizenship behaviours are defined as those behaviours which are not formally prescribed, but yet are desired by an organisation (Organ, 1988). Examples include punctuality, helping others employees, volunteering for things that are not required, making innovative suggestions to improve a department, and not wasting time (Bateman & Organ, 1983).

Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Moorman, and Fetter (1990) presented seven organisational citizenship behaviours: helping behaviour, sportsmanship, organisational loyalty, organisational compliance, individual initiative, civic virtue, and self development. Rego (1999) found in a Portuguese sample of managers four components: interpersonal harmony, initiative, conscientiousness, and identification with the organisation.

Konovsky and Pugh (1994), Lepine, Erez, and Johnson (2002), Bolino, Varela, Bande, and Turnley (2006), Gellatly, Meyer, and Luchak (2006), Lambert, Hogan, and Griffin (2008) considered the alternative of evaluating organisational citizenship behaviours as a sum of its dimensions, in the aggregate model, considering the concept in a global basis. Regarding the organisational citizenship behaviours, the study presented here chose to follow the recommendations of Law, Wong, and Mobley (1998) and LePine et al. (2002) and considered organisational citizenship behaviours as a unidimensional construct, as a tendency to be cooperative and help other employees in the workplace (Coleman & Borman, 2000).

Far as we know, there are no studies including Portuguese nurses or others samples of professions relating organisational and professional commitment with organisational citizenship behaviours.

Several studies have identified organisational commitment as an important antecedent of organisational citizenship behaviours (for example, Allen & Meyer, 1996; Gautam et al., 2005; Meyer & Allen, 1997).

Cohen (1999) and Lambert et al. (2008) found support for the consideration of organisational commitment as a construct for explaining the adoption of organisational citizenship behaviours.

Assuming that specific behavioural responses and specific organisational results relate mainly to certain forms of commitment (Becker & Billings, 1993), we expect people to respond to acts of citizenship benefactors of the organisation when they experience strong affective organisational commitment. Of the three components of commitment, affective commitment seems to have more desirable consequences for organisational behaviours (Allen & Meyer, 1996; Meyer & Allen, 1997).

Although the desire to remain in the organisation is distinct from the sense of obligation to do so, there seems to be some propensity for these feelings to co-occur, since affective and normative components, although distinct, are correlated. However, the correlations with the antecedents and consequences are stronger for affective organisational commitment than for normative organisational commitment (Dunham, Grube, & Castañeda, 1994).

Gautam et al. (2005), in a study in Nepal, found that affective and normative organisational commitments were more engaged with two dimensions of organisational citizenship behaviours: altruism and conscientiousness.

O’Reilly and Chatman (1986), Mayer and Schoorman (1992) and Organ and Ryan (1995) found a stronger relationship between affective organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours than between continuance organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours. Gautam et al. (2005) found a negative relationship between continuance commitment and obedience, and a non-significant relationship between continuance commitment and altruism. Chen and Francesco (2003) and Gellatly et al. (2006) found that continuance organisational commitment correlated negatively with organisational citizenship behaviours. McGee and Ford (1987) and Dunham et al. (1994) had already found support for dividing organisational continuance commitment in two sub-dimensions. Thus, it is stated that:

H1 – Organisational commitment is positively related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

H2 – Affective and normative organisational commitments are positively related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

H3 – The continuance dimension of organisational commitment, namely personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation and the lack of alternatives sub-dimensions, are negatively related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

There are few studies relating to professional commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours (Bogler & Somech, 2004; Cohen, 2006; Cohen & Kol, 2004; Meyer et al., 1993; Somech & Bogler, 2002).

The way an employee behaves in their work can be influenced by their commitment to the organisation and profession. As suggested by Meyer et al. (1993), it is possible that the relative influence of professional commitment is determined by the perception of how individual behaviour is important for the profession compared with its relevance to the organisation. If a behaviour is perceived as being within the values and principles of nursing, it may be more influenced by professional commitment than by organisational commitment.

Cohen and Kol (2004) showed that professionalism, and in particular when the dimension profession is used as referent, is a predictor of altruism and compliance dimensions of organisational citizenship behaviours. The professionalism is, in general, the identification and involvement in a particular profession. Morrow and Wirth (1989) considered the measure of professional commitment consistent with the measure of professionalism of Hall (1968). The dimension of professionalism profession as main referent corresponds to the measure of professional commitment. This means that professionalism involves the assessment of professional commitment; professional commitment is one of the dimensions of professionalism.

The Code of Practice for Portuguese Nurses, in articles 78 and 88, states that the principles guiding the work of nurses are the excellence in the exercise of the profession, both in a general way, and in relation with other professionals. The nurses have the duty to regularly review the work done and recognize that mistakes have to be fixed. These professional guiding principles can be the basis of organisational citizenship behaviours, such as not being late to work, respecting the rules of the hospital, and helping colleagues.

Meyer et al. (1993) advocated the extension of the model of organisational commitment to professional commitment, resulting in a three-dimensional model of professional commitment. In this study they found that affective and normative occupational commitments were positively associated with organisational citizenship behaviours, such as helping others and the use of time. For continuance occupational commitment the relationship found is not statistically significant (Meyer et al., 1993).

Based on these assumptions, we decided to formulate the following hypotheses:

H4 – Professional commitment is positively related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

H5 – Affective and normative professional commitments are related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

H6 – Continuance professional commitment is not related to organisational citizenship behaviours.

Directors of the hospitals that were the subjects of the study agreed to collaborate, and in the months of February, March, April and May 2009 questionnaires were given to the selected sample of nurses. The final version of the questionnaire is a document with two groups of questions. The first group includes questions relating to the identification of hospital and the identification with the service in which the individual works; nurses were asked about sex, age, marital status, employment status, occupational category, professional and organisational seniority, and category and service seniority. The second group included affective, continuance, and normative organisational commitment variables, affective, continuance, and normative professional commitment variables and organisational citizenship behaviours.

Respondents were asked to indicate the extent of their personal agreement using five-point scale (1=strongly disagree: 5=strongly agree).

In short, 1300 questionnaires were given; 420 were returned, so, considering the sample as a whole, the overall response rate was 32%.

The sample consisted of 420 nurses who practised their profession in two public hospitals: the Hospital of St. Marcos (Braga), and the Hospital Centre of Alto Ave (Guimarães and Fafe units), both in the north of Portugal. 182 nurses from the Hospital of St. Marcos, 203 nurses from the Hospital Centre of Alto Ave, Guimarães unit, and 35 nurses from the Hospital Centre of Alto Ave, Fafe unit, made up the final sample. This is a sample of convenience. The nurses belonged to a total of 33 different services.

2.2MeasuresThe scales of Meyer et al. (1993) and Meyer and Allen (1997) were constructed with data of samples of other professions, in another country. However, as we have a sample of Portuguese nurses, we decided to analyse if this sample is different from other samples what concerns to organisational and professional commitments. We decided to use factor analysis.

2.2.1Organisational commitmentTo measure organisational commitment, Ferreira scale was used (2005). It is the scale of organisational commitment of Meyer and Allen (1997), validated in the Portuguese context for the same population of nurses. This scale had 23 items. After subjected to internal consistency analysis the scale remain with 16 items.

The scale of organisational commitment was subjected to a principal component analysis by imposing a single factor. The value obtained in the KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) test for organisational commitment was .886. The Cronbach's alpha revealed that the factor has good internal consistency (α=.860).

To examine the dimensionality of organisational commitment, the commitment scale items were subjected to factor analysis, using the method of principal components. The construction factor obeyed the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue greater than 1). The method chosen was varimax rotation. The factorial analysis gave a solution with four factors. The scale of organisational commitment has a KMO of .824. The first factor corresponds to the affective dimension of organisational commitment, and the Cronbach's alpha of .79. The second factor includes the items listed in the literature as part of the component ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’ and has a Cronbach's alpha of .73, a value considered good. The third factor relates to the normative dimension of organisational commitment and has a Cronbach's alpha of .64. The fourth factor corresponds to the continuance dimension – the ‘lack of alternatives’ subdimension. The Cronbach's alpha is .60. The factor analysis showed two dimensions in the continuance organisational commitment.

2.2.2Professional commitmentThe scale of professional commitment was subjected to principal component analysis by imposing a single factor. The value obtained in the KMO test for professional commitment was .809. The calculation of internal consistency by Cronbach's alpha shows that the factor has good internal consistency (α=.78). To measure professional commitment is used Meyer et al. (1993) scale and two items of Blau (2001) scale. The reasons for using this scale relate to the fact that they conceptualized commitment as a multidimensional construct, in line of the latest perspectives on study of commitment. Moreover, these researchers applied the tridimensional model to occupations. The original scales were translated to Portuguese with the help of an English native speaker. After the analysis of internal consistency remained 17 items: 6 items for the affective professional commitment, 6 items for continuance professional commitment and 5 items for normative professional commitment.

To examine the dimensionality of professional commitment, a principal components analysis with varimax rotation was carried out, following the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalue greater than 1).

The factorial analysis results in five factors. The last two factors were not interpretable and had very low Cronbach's alphas, so we decided to eliminate them. The professional commitment scale has a KMO of .827. The extracted factors relate respectively to the affective dimension (α=.78), the continuance dimension (α=.76) and the normative dimension of professional commitment (α=.62).

2.2.3Organisational citizenship behaviourRego (1999) presented for a sample of managers four dimensions of organisational citizenship behaviours: interpersonal harmony, initiative, conscientiousness and identification with the organisation. The Rego scale (1999), although it has been validated in Portuguese context, revealed several items that did not fit to the nurses sample. The scale of Coleman and Borman (2000) proved to be most appropriate to the sample and to the results of exploratory interviews. The scale of organisational citizenship behaviours resulted of the adaptation of twenty-seven items by Coleman and Borman (2000) scale. Some items of Podsakoff and MacKenzie (1994) scale were used and were created new items as suggested by exploratory interviews. The original scales were translated to Portuguese, with the help of an English native speaker. The scale consisted in 32 items. After the pretest remained 21 items.

In the early exploration of the scale factor of organisational citizenship behaviours, we chose to do a factor analysis of the principal components with varimax rotation, according to the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues greater than 1), in order to explore the possibility of several factors. This factor solution did not prove appropriate, because the factors ascertained were dubious in the light of dimensional perspective of organisational citizenship behaviours. The experiment was done by forcing the extraction of a factor and the solution was more intelligible than extraction with eigenvalues greater than 1 or with limitation of two, three or five factors. Other authors also seem to have opted for a global measure of organisational citizenship behaviours or a one-factor solution (Gellatly et al., 2006; Konovsky & Pugh, 1994; Lambert et al., 2008; LePine et al., 2002).

The value obtained in the KMO test was .878. The Cronbach's alpha shows that the factor has a good internal consistency (α=.87).

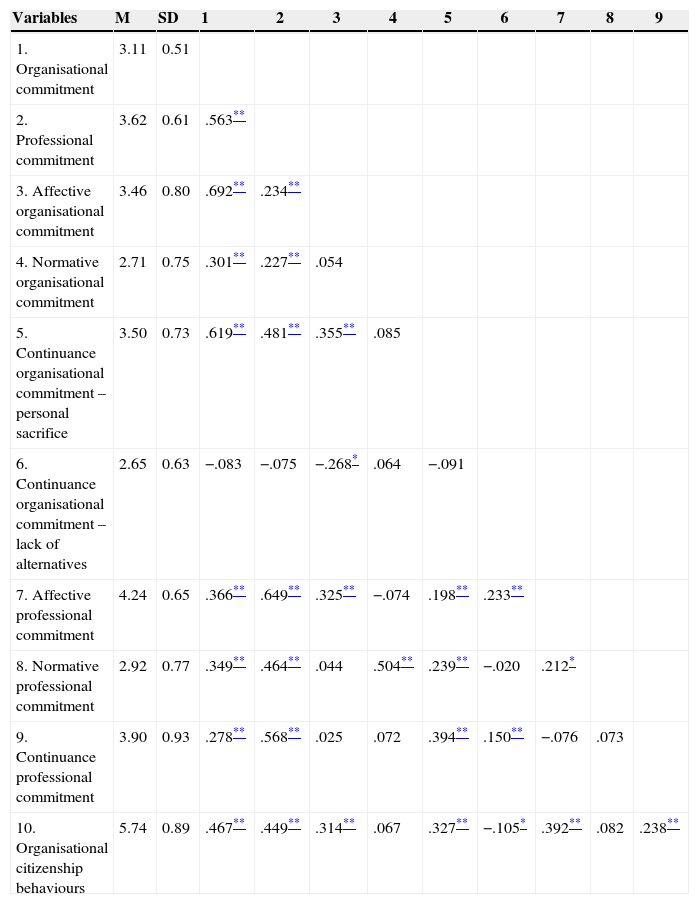

3ResultsTable 1 presents the correlations with statistical significance between the study variables.

Correlations between commitments and organisational citizenship behaviours.

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Organisational commitment | 3.11 | 0.51 | |||||||||

| 2. Professional commitment | 3.62 | 0.61 | .563** | ||||||||

| 3. Affective organisational commitment | 3.46 | 0.80 | .692** | .234** | |||||||

| 4. Normative organisational commitment | 2.71 | 0.75 | .301** | .227** | .054 | ||||||

| 5. Continuance organisational commitment – personal sacrifice | 3.50 | 0.73 | .619** | .481** | .355** | .085 | |||||

| 6. Continuance organisational commitment – lack of alternatives | 2.65 | 0.63 | −.083 | −.075 | −.268* | .064 | −.091 | ||||

| 7. Affective professional commitment | 4.24 | 0.65 | .366** | .649** | .325** | −.074 | .198** | .233** | |||

| 8. Normative professional commitment | 2.92 | 0.77 | .349** | .464** | .044 | .504** | .239** | −.020 | .212* | ||

| 9. Continuance professional commitment | 3.90 | 0.93 | .278** | .568** | .025 | .072 | .394** | .150** | −.076 | .073 | |

| 10. Organisational citizenship behaviours | 5.74 | 0.89 | .467** | .449** | .314** | .067 | .327** | −.105* | .392** | .082 | .238** |

The correlation analysis shows that nurses’ organisational commitment is correlated to organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.467, p<.001) and nurses’ professional commitment is correlated to organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.449, p<.001).

Affective organisational commitment reported to be more engaged with organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.314, p<.001); continuance organisational commitment based on personal sacrifice is correlated with organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.327, p<.001) and continuance organisational commitment based on the perceived lack of alternatives is related negatively with organisational citizenship behaviours (r=−.105, p<.05).

Affective professional commitment is correlated with organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.392, p<.001) and continuance professional commitment is correlated with organisational citizenship behaviours (r=.238, p<.001).

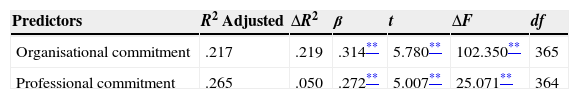

Table 2 displays the results of regression analysis.

Through the stepwise method ‘organisational commitment’ and ‘professional commitment’ variables were included in the model. The variables with a non-significant β were excluded from the explanatory model. This set of variables belongs to the explanatory model of organisational citizenship behaviours, explaining 26.5% of the variance in organisational citizenship behaviours.

The column with the β values shows that the variable with the greatest predictive power on organisational citizenship behaviours is organisational commitment (β=.314, p<.001) followed by professional commitment (β=.272, p<.001). It can be concluded that organisational citizenship behaviours are explained by a higher organisational commitment and a greater professional commitment.

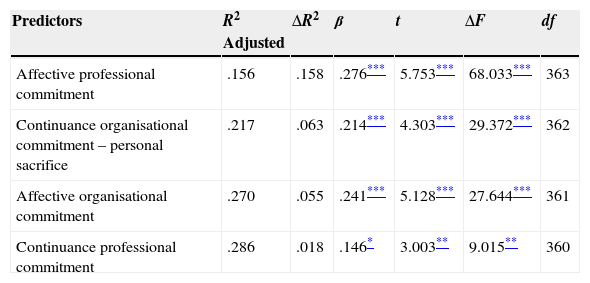

Table 3 displays the results of regression analysis, giving the dimensions of commitment.

Explanatory model of organisational citizenship behaviours (including dimensions of organisational and professional commitment).

| Predictors | R2 Adjusted | ΔR2 | β | t | ΔF | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective professional commitment | .156 | .158 | .276*** | 5.753*** | 68.033*** | 363 |

| Continuance organisational commitment – personal sacrifice | .217 | .063 | .214*** | 4.303*** | 29.372*** | 362 |

| Affective organisational commitment | .270 | .055 | .241*** | 5.128*** | 27.644*** | 361 |

| Continuance professional commitment | .286 | .018 | .146* | 3.003** | 9.015** | 360 |

Through the stepwise method ‘affective professional commitment’, ‘continuance organisational commitment – personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’, ‘affective organisational commitment’ and ‘continuance professional commitment’ variables were included in the model.

This set of variables integrates the explanatory model of organisational citizenship behaviours, explaining 28.6% of the variance in organisational citizenship behaviours.

The column with the β values shows that the variable with the greatest predictive power on organisational citizenship behaviour is affective professional commitment (β=.276, p<.001), followed by continuance organisational commitment – ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’ (β=.214, p<.001), affective organisational commitment (β=.241, p<.001) and continuance professional commitment (β=.146, p<.05).

It can be concluded that organisational citizenship behaviours are explained by a higher affective commitment to the profession, a greater continuance organisational commitment – ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’, a higher affective organisational commitment and a greater continuance professional commitment.

4Discussion and conclusions4.1Organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behavioursThe present investigation is grounded on a multidimensional and multifocal framework in line with the work of Morrow (1983, 1993), Randall and Cote (1991), Becker (1992), Cohen (1993, 1999, 2006). Most studies have focused mainly on organisational commitment, especially in its affective dimension, and its relationship with organisational citizenship behaviours, putting aside other foci of commitment and their dimensions.

Support was found for hypothesis 1, which stated that organisational commitment is capable of explaining the variability in levels of organisational citizenship behaviours adopted. Organisational commitment is related to organisational citizenship behaviours. Nurses attached to the hospital, and who feel identified, involved and willing to make a sacrifice for it, tend to display more organisational citizenship behaviours. This therefore confirmed the status of the important variable on the part of organisational commitment in relation to organisational citizenship behaviours. In a perspective of exchange, nurses who feel committed with the organisation tend to reciprocate contributing to good organisational performance and exceeding the formal requirements of their duties.

The multiple regression analysis for organisational citizenship behaviours also revealed that when entering into the model the dimensions of organisational commitment, the variables with the greatest explanatory power are continuance organisational commitment – ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’, and affective organisational commitment.

When we include the dimensions of organisational commitment, it is concluded that the explanatory power increases, leading to the conclusion that a better explanation of organisational citizenship behaviours can be obtained when taking into account the dimensions of commitment. Thus, there is justification for considering the multidimensional nature of organisational commitment in explaining organisational citizenship behaviours.

For the dimensions of organisational commitment, the second hypothesis which predicted the inclusion of the affective and normative organisational commitment variables in explaining organisational citizenship behaviours found only partial support. Multivariate analysis allowed us to partially confirm hypothesis 3, which negatively related continuance organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours. Also, the continuance organisational commitment subdimension ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’ was found to explain the organisational citizenship behaviours.

The principal components factor analysis revealed for this study four dimensions of organisational commitment: affective organisational commitment, normative organisational commitment, continuance organisational commitment – ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’ and continuance organisational commitment: ‘lack of alternatives’. This study pointed to two subdimensions of continuance organisational commitment in line with the work of Dunham et al. (1994) and McGee and Ford (1987). Based on this work, the consideration of continuance organisational commitment as a two-dimensional construct has been suggested. Indeed, as will be seen, the contribution of each subdimension to the explanation of organisational citizenship behaviours is different, making sense of the partitioning of the concept.

The positive effect of affective organisational commitment has already been shown (Gautam et al., 2005; Gellatly et al., 2006; Kuehn & Al-Busaidi, 2002; Podsakoff et al., 2009; Wasti, 2005), so the present study confirms these results. Employees affectively committed support voluntarily their colleagues and defend and promote the organisation, because they have the desire to do something more for the organisation that goes beyond the role description associated with their jobs.

The relationship between organisational normative commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours, although positive, was not statistically significant. One possible explanation could be that employees do not perform organisational citizenship behaviours to fulfil their obligations or just to show your gratitude to managers or to colleagues. The desire to do something for the organisation can be stronger than the duty to go beyond what is required in the role, or stronger than the feeling of gratitude to superiors or to coworkers.

One of the main contributions of this study relates to the explanatory weight that is given to the ‘personal sacrifice’ subdimension of continuance organisational commitment in the profile of the nurse as a good organisational citizen. Previous studies had not explored this subdimension and this research has demonstrated the importance of separation in the case of this sample. The need to conduct more investigation into this relationship is emphasized here; however, there is the possibility that nurses may feel both a strong affective commitment and an intense continuance commitment – ‘personal sacrifice’, and within this profile, sacrifices/bets are at stake other than the traditional ones: for example, loss of satisfactory working conditions (Gellatly et al., 2006). It is possible that for employees with an intense affective organisational commitment, the costs of abandonment are seen differently to those with a weak affective organisational commitment. The former may consider the loss of positive work experiences that contribute to affective organisational commitment, and potential abandonment costs, while the latter may focus more on the economic costs associated with leaving the organisation. The satisfactory work experience could serve as a powerful antecedent of affective and continuance organisational commitments and thus explain why employees affectively and calculatively linked to the organisation exhibit organisational citizenship behaviours.

The relationship between affective organisational commitment and continuance organisational commitment – ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’ subdimension can be interpreted in light of the theory of self-justification or the cognitive dissonance theory (Somers, 1993). Ties based on the costs/sacrifices for the organisation can be explained cognitively, being transformed into a greater emotional connection for the organisation, in order to mitigate the reality that is based on the failure to leave the organisation due to costs/sacrifices associated with leaving.

4.2Professional commitment and organisational citizenship behavioursThe data collected in this study show that professional commitment is related to nurses’ citizenship behaviours. The results confirm hypothesis 4. In fact, the nurses’ connection with their profession explains in part the good organisational citizenship profile.

Empirical data showed the importance of the inclusion of professional commitment in explanatory models of organisational citizenship behaviours and this is a significant contribution of this study. This study extends the previous ones (Cohen, 1999, 2006) by giving prominence to professional commitment in explaining organisational citizenship behaviours. More recent studies have validated the additional predictive ability of professional commitment in explaining the behaviour of employees at work (Tsoumbris & Xenikou, 2010).

It is possible that the relative influence of organisational and professional commitments is determined by the perception of how important this behaviour is to the profession compared to what it is for the organisation. The Code of Practice of Nursing (article 90, paragraph b) states that it is the duty of nurses to be supportive of other members of the profession in order to dignify the profession. Thus, helping colleagues, guiding new colleagues, keeping colleagues informed about conferences are behaviours that are professional. In the same article, in paragraph a), refers to nurses’ duty to maintain a high standard of personal conduct in the performance of their activities in order to dignify the profession. Not taking unnecessary breaks and demonstrating compliance with the rules of the hospital are examples of behaviours that display a high standard of personal conduct not only to preserve the image of the profession but also to improve organisational performance.

Regarding the dimensions of professional commitment, affective professional commitment appears in the regression models as the most prominent variable explaining the largest proportion of variance in organisational citizenship behaviours. Consistent with these results, we grant only partial support to hypothesis 5, which stated that the affective and normative dimensions of professional commitment explained the variability in organisational citizenship behaviours, towards a higher level of this class of behaviours.

It was expected that the normative component of the professional commitment would represent an important role, but this did not happen, as in the case of normative organisational commitment. When a nurse is connected normatively to her profession she feels obligation, duty and responsibility to stay in it. The sense of duty and obligation is a concept that should be considered in the light of the culture of a country and of the specific culture of each organisation. The normative commitment may derive from cultural expectations. Feeling obligated, having a duty, may be interpreted as the absence of freedom and power of choice, and this interpretation could lead to respondents positioning themselves less favourably in this demonstration of commitment.

In the present study, the normative professional commitment was not related to organisational citizenship behaviours, which may be due to the fact that nurses demonstrate a weak normative link to the profession, a conclusion which is in line with that of another study in the Portuguese context based on nurses (Leite, 2007).

Nurses emotionally attached to their profession – i.e. who have an emotional bond to the profession, believe in their values and goals and are willing to exert extra effort on behalf of the profession – tend to display more organisational citizenship behaviours. It may be that they see the hospital organisation as a context for professional development which should defend and support if they could keep this context. As the hospital is a professional organisation, the values and goals that it advocates have a greater chance of being in line with the values and goals of those professional groups which are integrated within it.

The hypothesis 6 was refuted. Regarding the continuance component, research has ignored this dimension of commitment, but given the results obtained here, exploring this dimension in the prediction of organisational citizenship behaviour seems to be of some interest. The nurses with continuance professional commitment do not leave because they feel that they have invested in it and that there are costs associated with such an abandonment that would be lost, and there are no perceived alternatives.

The calculation of investments/losses does not inhibit nurses from being simultaneously affectively linked to the profession. And even if a conflict were perceived in an attempt to resolve this dissonance, the nurse could, over time, show affection for profession. The two dimensions of commitment may be related over time, as noted by Meyer et al. (1993), and it may happen that one does not develop without the other, which underlies the relationship between affective professional commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour and continuance professional commitment and organisational citizenship behaviour.

4.3Limitations, practical implications and future avenues for researchThis study has, however, some limitations. The low level of internal consistency (less than 0.70) of some of the scales used, particularly of normative organisational commitment, normative professional commitment and continuance organisational commitment – lack of alternatives, may have influenced the results, make it advisable that in future studies, this limitation should be exceeded. In the case of the normative dimensions of organisational and professional commitments, the revision of the scale may be useful in order to understand the true nature of this type of commitment. Meyer and Allen (1997) carried out this revision, but more attention must be paid when you are faced with a culturally different context from the original sample, which demands some effort in the translation and the applicability of the items. The continuance organisational commitment – ‘lack of alternatives’ has only two items, which according to some authors is insufficient to measure what is intended. New descriptors should be encouraged, which have to do with the nature of this type of commitment and contribute to increasing their separation from another subdimension of continuance organisational commitment: ‘personal sacrifice associated with leaving the organisation’.

This study did not follow some of the research on organisational citizenship behaviour, which studied the independent variables and the dependent variables from different sources, often using self-descriptions, in the case of independent variables, and evaluation of the supervisor, in the case of dependent variables. We decided not to sacrifice the size of the sample. On the other hand, it is known that the evaluations of supervisors do not guarantee objectivity of the data because they are subject to biases, distortions and errors (Khalid & Ali, 2005; Robinson & Morrison, 1995).

Limitations should include also the possible variance in the study introduced by the demographics of the sample. We did not explored this possibility in this study, but is a goal in future studies.

All of the measures appear to be from a single survey instrument given at a single time. This makes it difficult to determine causality. Organisational citizenship behaviours were self-rated. This would tend to be inflated due to social desirability. Finally, it must be remembered the possible confounding effect of a Portuguese sample on our results.

This study highlights the importance of organisational commitment in relation to nurses’ organisational citizenship behaviours, including affective dimension and continuance dimension (personal sacrifice). It also emphasizes the importance of studying the effect of professional commitment and its dimensions (affective and continuance) in the profile of a good organisational citizenship behaviours.

The results of this research should also be regarded as capable of guiding the actions of managers in the day-to-day, within organisations, with regard to the promotion of citizenship organisational behaviours. Managers must promote the development of this type of behaviour considered beneficial to the organisation, using for this purpose human management resource techniques.

It is of particular importance to ensure that nurses have the necessary skills to carry out organisational citizenship behaviours and, moreover, do not replace their professional duties and responsibilities for these discretionary behaviours. The organisational citizenship behaviours, when encouraged to supply deficiencies in terms of human and financial resources, may be indicators of poor personnel management and may hide weaknesses in hospital management.

The job insecurity is followed by an hospital instrumental view regarding human resources. This attitude from the hospital management does not lead to the development of organisational commitment, especially affective and normative dimensions, dimensions that are considered important to the development organisational citizenship behaviours. This warning is especially important for hospitals public enterprise, which, claiming economistic reasons, have bet in precarious contracts. The development of organisational commitment and organisational citizenship behaviours may involve the recruitment and selection techniques. It is important to attract nurses with a profile in terms of values that fit the profile that the hospital wants. In relation to professional commitments, the hospital management should not forget the values and objectives of nursing, in order to generate compatibility of views and interests, and to support the nurses’ identification with the hospital.

This study suggests some reflection on the future avenues for research. Researchers interested in these fields of research could also explore to what extent the distinction of organisational citizenship behaviours based on the salient focus for nurses would be a surplus value in terms of research. Citizenship behaviours directed to the patient, citizenship behaviours directed to co-workers and citizenship behaviours directed to the hospital would have distinct classes of organisational and professional commitment. It would also be interesting to compare the organisational citizen profiles of nurses without specialisation and with specialisation, to compare citizen organisational profiles of nurses with higher or lower organisational and professional seniority. The study of these variables could improve understanding of organisational citizenship behaviours of nurses.