En España, existen dos tipos de condenas para los agresores contra la pareja: la pena de prisión y la medida alternativa a esta, en concreto los programas de intervención psicosocial. El objetivo de este estudio es conocer las diferencias en perfil delictivo y psicopatológico de estos agresores según la condena recibida, para lo cual se han seguido los modelos propuestos por Dutton (1995) y Holtzworth-Munroe y Stuart (1994). La muestra está formada por 50 agresores en prison y 40 condenados a medidas alternativas (programa/intervención). Las variables se han obtenido a través de un método mixto con supervisión de expedientes penitenciarios, entrevista clínica para el trastorno de personalidad (SCID-II) y autoinforme para el perfil de personalidad (NEO-PIR). Se ha utilizado la regresión logística binaria para identificar el modelo final que mejor señala las diferencias de ambos grupos. Los resultados describen el perfil de los agresores en prisión con mayor número de factores de riesgo alterados, tanto a nivel socioeconómico, como delictivo y psicopatológico. Las tres variables que aumentan las probabilidades de pertenencia al grupo de prisión según el modelo final obtenido son: uso de armas, consumo de drogas y trastorno de personalidad. La elevada incidencia en los resultados de las variables a estudio, a diferencia de otras investigaciones principalmente en consumo de drogas y trastorno de personalidad, nos hace plantearnos si ha influido el método diagnóstico utilizado, contrario al uso exclusivo de autoinformes, objetivo a confirmar en próximos estudios.

In Spain, there are two types of sentence for partner aggressors: prison sentence and the alternative measure, specifically psychosocial intervention programs. The goal of this study was to determine differences in the delinquent and psychopathological profile of these aggressors as a function of the prison sentence received, for which the models proposed by Dutton (1995) and Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) were followed. The sample was made up of 50 incarcerated aggressors and 40 men sentenced to mandatory community orders. The variables were obtained through a mixed method, with supervision of penitentiary case files, clinical interview for personality disorder (SCID-II), and self-reports for the personality profile (NEO-PI-R). Binary logistic regression was used to identify the final model, which best reveals the differences between both groups. The results describe the incarcerated aggressors' profile as having more altered risk factors at the socioeconomic, delinquent, and psychopathological levels. The three variables that increase the probability of belonging to the prison inmate group, according to the final model obtained were: use of weapons, drug consumption, and personality disorder. In contrast to other investigations, the high incidence in the outcomes of the target variables, mainly drug use and personality disorder, makes us wonder whether the diagnostic method used influenced the results in contrast to the exclusive use of self-reports, a goal to be confirmed in future studies.

During the past two decades, partner violence (PV) has represented one of the most worrisome forms of interpersonal violence, given the alarming worldwide statistics, violence involving the murder of one's partner, physical and/or sexual violence, harassing, psychological violence, as well as emotional abuse that is difficult to denounce, but with important consequences in terms of suffering and subjugating women's free will (Caetano, Vaeth, & Ramisetty-Milker, 2008). According to the World Health Organization (2013), PV can be considered a worldwide epidemic, because 38% of the murdered women and 42% of the women who were physically and/or sexually assaulted were attacked by their partners or ex-partners. PV is considered the most common type of violence against females. Although Asia and the Middle East are the areas with higher incidence, in Europe the numbers show that this situation is also severe. According to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014), 22% of women have suffered physical and/or sexual violence, 43% psychological aggression, and 55% sexual harassment.

The legal reforms generated in Spain against gender violence, initiated with the Organic Law 1/2004 of Measures of Integral Protection, have shed public light on a large part of aggressions formerly concealed within the family, by providing victims with legal protection and support to enable them to file a complaint. The statistics of PV present two realities, the number of complaints, which year after year increases, and the real number of aggressions with or without a complaint, which can only be known though estimation by means of macro-surveys. The increase in complaints does not indicate an increase of aggressions, but an increase in the sensitization towards this problem, with the onset and subsequent development of this type violence being common characteristics of the complaints. Thus, aggressions normally emerge during the first years of the relationship, even while dating, presenting an approximate duration of 10 years, with variations between some months and 50 years due to the victim's economic and mainly emotional dependence, as she wants the aggressions to end but not the relationship (Menéndez, Pérez, & Lorence, 2013).

The types of prison sentence that can be applied to aggressors, depending on the severity of the acts, are deprivation of freedom at the first offense and alternative measures to prison such as community service and/or mandatory community intervention programs (Fariña, Arce, & Buela-Casal, 2009). Currently, according to the statistics of the Spanish Secretary of State of Penitentiary Institutions (Secretaría de Estado de Instituciones Penitenciarias, 2013), there are 3,900 men incarcerated for this type of crime and 45,937 men were sentenced to alternative measures during 2012, of whom 30,225 were sentenced to community service and 15,712 to mandatory community intervention.

Explanatory models addressing the complex phenomenon of PV adopt diverse perspectives, such as the sociological theories of power relations and men's domination of women, the psychopathological characteristics of the aggressors, establishing their typologies, or focusing on the relational dimension of violence, such as interpersonal conflict in the couple relation (Dobash & Dobash, 1984; Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Stuart, 2005; Walker, 1984). A conjunction of these proposals is the functional model of Dutton (1995), which provides a complete list of the diverse risk factors that intervene in these violent acts. Following this model, Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, and Tritt (2004), by means of a meta-analysis, identified a broad description and justification of risk factors, grouping them according to four levels of inclusiveness: (a) macro-system or social influence level, made up of the factors of Culture, Social Values, Ideology, and Social Beliefs; (b) exo-system or community influence level, which include work, educational level, occupational/life stress, violence against relatives (other than the partner), economic income, prior arrests, and age; (c) micro-system or group influence level, describing risk variables such as being a victim of child abuse, provoking forced sexual relations, harassing, level of satisfaction with the couple relation, separation from the partner, level of control over the partner, cruelty to animals, jealousy, provoking emotional and/or verbal abuse, and the history of partner aggressions; and (d) ontogenic level, with exclusive characteristics of the aggressor, which include illegal drug abuse, hatred/hostility, attitudes justifying violence against women, traditional ideology in sex roles, depression, alcohol abuse, and empathic capacity.

One of the most recent proposals of the functional model ratifying the model of Stith et al. (2004) was carried out by Capildi, Knoble, Shortt, and Kim (2012), who made a systematic review of 228 studies of risk factors in PV. These authors conceptualize aggression as a dynamic or functional system, where the characteristics of the aggressor and the victim, along with the social context and type of relation, interact, provoking aggression. Risk factors are classified as sociodemographic variables, characteristics of the social environment, factors acquired during development (childhood violence, type of parenting, peer group, support network), psychological and behavioral factors (psychopathological disorders, personality disorders, alcohol and drug abuse, self-esteem, antisocial behavior), cognitive factors (hostile attitudes and beliefs), and lastly relational risk factors (satisfaction, jealousy, attachment).

The aggressors' characteristics are also extensively described by the models of typologies of aggressors and the most frequently cited is that of Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994), who define three types of aggressors with predominance of a certain personality disorder and a certain type of violence in each one. Thus, they identify: aggressors who only assault relatives, who show a prevalence of passive-aggressive disorder, which is typical of psychological maltreatment; men with generalized aggressiveness towards all kinds of people, with a high incidence of antisocial disorder; and, lastly, aggressors who are emotionally unstable, frequently diagnosed with borderline personality disorder who display cyclic aggressiveness exclusively towards the partner.

Other studies focus on men sentenced to mandatory community intervention, as alternative measures to prison, with the main goal of matching the therapeutic programs to the profile of these individuals. In a study by Novo, Fariña, Seijo, and Arce (2012), the authors describe these aggressors as having high levels of hostility, persecutory ideas, and depressive symptomatology. According to these authors, a key element for intervention is to address the individual's violent thoughts, or "toxic cognitions", due to their internal, stable, and global nature, because when they are associated with depressive states and attacks of rage they are the propellers of violent acts. In this type of aggressors, low alcohol consumption, being young, low level of impulsivity, a longer prison sentence, as well as high levels of anxiety and depression are protector factors against recidivism after treatment (Lila, Oliver, Galiana, & Gracia, 2013).

The diversity of results in the studies on PV, especially those that appraise personality disorders, is mainly explained by differences in the diagnostic tools and the origin of the sample. The habitual use of self-reports has been observed, especially the MCMI, a strategy that restricts the appraisal of personality, taking into account the high social desirability and/or reading comprehension difficulty of most prison inmates (Amor, Echeburúa, & Loinaz, 2009; Dutton, 2003). To overcome these limitations in research, some authors have used the review of historical data through police and/or judicial case files, along with diagnostic interviews by specialized personnel (Belfrage & Rying, 2004).

In spite of the diversity of aggressors' characteristics, the literature reveals some factors as more relevant: coming from underprivileged socioeconomic levels, having been a victim and/or a witness of violence in childhood, having a violent history (in general or with the partner), abusive consumption of alcohol and/or drugs, presence of important psychopathological disorders, distorted cognitive processing of violent acts, and deficit of the social support network (Menéndez et al., 2013).

The identification of the characteristics of partner aggressors would allow us to adapt the therapeutic programs, seeking lower rates of recidivism. According to the meta-analysis of the efficacy of this type of programs carried out by Arias, Arce, and Vilariño (2013), the aggressors' needs, psychopathological and/or psychiatric characteristics, compliance with treatment, psychological adjustment, and motivation to change are all key factors in the design of the treatment. Likewise, long programs are recommended in order to address cognitive distortions, which are strongly consolidated and resistant to change in this type of aggressors. Due to the characteristics of partner aggressors, such as unwilling participation (by court order, to avoid the prison sentence or to obtain penitentiary benefits), specialized personnel must apply the intervention, and additional judicial measures are suggested (Lila, García, & Lorenzo, 2010).

Within the risk factors of PV, a large number coincide with the factors proposed in research on diverse delinquent profiles, as being common factors to all of them. Studies of this type of factors in penitentiary population have in general extracted the profile of the inmate of Spanish prisons, defined as male, younger than 40 years old, with socioeconomic lacks, low educational level, scarce professional qualification, drug consumer (between 60-70%), and with psychopathological alterations and personality disorders (Casares-López et al., 2010; Salize, Dressing, & Kief, 2007; Vicens et al., 2011). Precipitating factors of delinquent recidivism were found, especially psychopathy and/or drug addictions, severe acts, and having been incarcerated at an early age (García, Moral, Frías, Valdivia, & Díaz, 2012; Rodríguez et al., 2011). These factors coincide with the descriptors of offending youths who end up going to prison as adults (Contreras, Molina, & Cano, 2011).

The legal variations of the sentence of mandatory community intervention generates a new space for investigation with the goal of appraising the profile of these aggressors, who are considered as being at lower risk because the judge substituted the prison sentence as it was less than two years. Identifying these characteristics allows us to adjust the obligatory treatment and to appraise whether it should be different from that received by the aggressors sentenced to prison. Some studies of this type of aggressors appraise psychopathological symptomatology, the personality profile by means of the MCMI-II, distorted ideas about women and violence, hostility and persecutory ideas, and the characteristics of the aggression by means of the CTS-2 (Boira & Jodrá, 2010; Echauri, Fernández-Montalvo, Martínez, & Azcárate, 2011; Novo et al., 2012; Redondo, Graña, & González, 2009). We think it is necessary to advance in the same vein of research, studying in more depth other risk factors such as delinquent characteristics and appraising criminal records, the violence employed, the use of weapons, generalization of the aggressions, and noncompliance with other judicial measures. Another goal is the appraisal of the differential personality profile of these two types of sentenced individuals from two diverse perspectives: on the one hand, the non-pathological personality profile by means of Big Five model (Costa & McCRae, 1985) and, on the other hand, the study of the typical personality disorders in the typologies of aggressors, using a different strategy from self-reports such as the MCMI by means of a structured clinical interview and review of case files.

Method

Participants

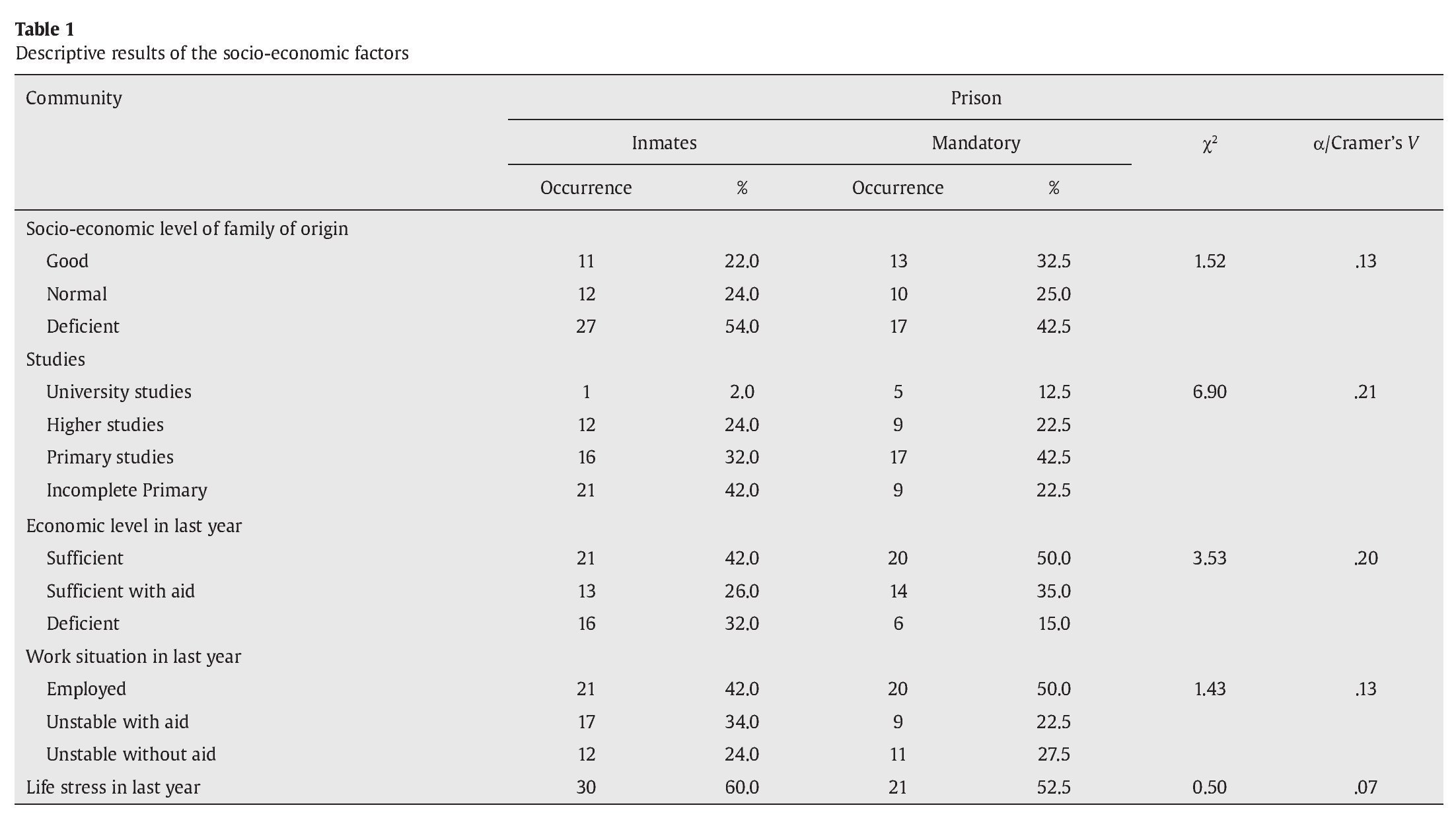

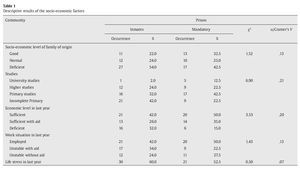

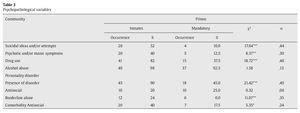

The sample is made up of 90 males sentenced for PV, distributed in two groups as a function of the type of sentence, a group of prison inmates (PI), and a group of mandatory community intervention programs (MCIP) sentenced to receiving psychosocial intervention programs as an alternative measure to prison. The prison inmate group is made up of 50 participants from the Penitentiary Center of Alicante-II (Villena, Alicante, Spain) and that of mandatory community includes 40 participants from the Sentence and Alternative Measures Management Service of the Region of Murcia (Spain). Mean age of both groups was 35 years (PI: M = 35.8, SD = 9.33; MCIP: M = 35.2, SD = 7.74), concentrated in the age ranges between 26 and 35 years (PI: 44%; MCIP: 50%) and between 36 and 45 years (PI: 28%; MCIP: 27.5%), with no significant differences between the groups, t(88) = 0.34, ns, Cohen's d = 0.08. The rest of the sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1, where the group of prison inmates stands out from that of mandatory community because they come from a family with a deficient socioeconomic level (PI: 50%; MCIP: 27.5%), without occupational qualification (PI: 92%; MCIP: 70%), and with a deficient economic level (PI: 32%; MCIP: 15%). The majority is of Spanish nationality in both samples, although there are also South Americans in the group of mandatory community (PI: 6%; MCIP: 37.5%).

The inclusion criteria were: being sentenced for PV, voluntary participation in the study, as well as the capacity to read and understand Spanish. Exclusion criteria were: having undergone prior psychological therapy for PV and a deficient cognitive level to participate in a psychological assessment.

Instruments

The variables of the study were the common risk factors of diverse criminal typologies, identified in aggressors of PV, according to the models of Stith et al. (2004) and Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994). These common factors were distributed in three blocks: socio-economic, delinquent, and psychopathological. As assessment method we used the interview and self-reports, along with supervision of the expert technical case files of the penitentiary institutions (e.g., police officers, psychologists, social workers, health professionals, judicial agents, and prison officers). The review of these case files allowed us to contrast the truthfulness of the information provided in the interview, attempting to control the high social desirability of this collective:

a) Review of the penal, penitentiary, and social case files. These three case files contain the necessary information to execute the sentence handed down by the judge, and diverse risk factors can be extracted from them. These are the following, according to the above-mentioned blocks: socio-economic risk factors (age, nationality, socio-economic level of the family of origin, occupational qualification, studies, economic level, work situation the year before being sentenced, and occupational/life stress); delinquent risk factors describing the characteristics and history of the crimes committed (violence against relatives other than the partner, violence against non-relatives, criminal records, victim and/or witness of violence in childhood, breaking parole of conditional freedom or other court measures, and prison sentence for the use of weapons and/or believable threats of death); and psychopathological risk factors (suicidal ideas and/or suicide attempts, psychotic and/or manic symptoms, drug consumption, and alcohol abuse).

b) SCID-II (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-II Personality Disorders), (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Smith, 1999) Spanish versión to assess the risk factor Personality Disorder, through the antisocial, borderline, and aggressive-passive disorders, as proposed by Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) in their classification of aggressors, as the most significant disorders. The diagnosis was made by examining the criteria established by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) classification for each disorder, information provided in the structured interview, and completed with the data extracted from the case file. Each criterion is scored as a function of behavior duration: (3) permanent, (2) occasional, (1) non-existent, and (?) insufficient information. The interview for antisocial disorder explores the four proposed diagnostic criteria, in two parts. Part A examines the behavior patterns before 15 years of age with 15 items and the result is positive if two items are marked with a (3) permanent score. Part B is carried out if part A is positive, exploring behaviors after the age of 15 through 7 items: a permanent score of (3) in three items is required to make the diagnosis of antisocial disorder. The studies of reliability show a kappa index between .78 and .91 (Lobbestael, Leurgans, & Amtz, 2010; Maffei et al., 1997), and in our case an inter-interviewer kappa of .81 and an inter-encoder kappa of .73.

c) Self-reports:

- Questionnaire of variables elaborated ad hoc with the goal of complementing the information obtained from reviewing the case files, because not all of them provide complete data of the risk factors. When obtaining information contrary to that obtained from the case file the case file data prevailed, being considered more reliable because it had been gathered by diverse professionals such as police officers, health and judicial professionals, and penitentiary officers. This questionnaire explores the same sociodemographic, psychopathological, and delinquent variables that are assessed in the review of the penal, penitentiary, and social case file.

- Personality Inventory Revised (NEO PI-R) (Costa & McCrae, 1992), Spanish adaptation (Arribas, 1999). This is a personality questionnaire based on the Big Five Model (Costa & McCrae, 1985), obtaining the non-pathological personality profile across five domains, each one made up of six facets: (N) Neuroticism: Anxiety, Irascible Hostility, Depression, Self-Awareness, Impulsivity, Vulnerability; (E) Extroversion: Warmth, Affiliation, Assertiveness, Activity, Excitement Seeking, Positive Emotions; (O) Openness to Experience: Fantasy, Esthetics, Feelings, Actions, Ideas, Values; (A) Agreeableness: Confidence, Honesty, Altruism, Deference, Modesty, Benevolence; and (C) Responsibility: Capacity, Order, Sense of Duty, Achievement Seeking, Self-Discipline, Caution. With this questionnaire we obtain the measures of two risk factors for PV - the levels of Hostility and Depression - which are two facets of the dimension of Neuroticism. The inventory is made up of 240 items suggesting different ways of thinking, behaving, or feeling. Participants rate their agreement with the statements on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The version used presents internal consistency coefficients ranging between .82 (Openness) and .90 (Neuroticism).

Procedure and Design

This is a descriptive, relational, cross-sectional study, which began with the corresponding authorizations of the Secretaría de Estado de Instituciones Penitenciarias [Spanish Secretary of State of Penitentiary Institutions] and target penitentiary centers. The sample of the prison inmates was obtained from all the men serving a sentence for PV in the Penitentiary Center of Alicante-II, and participation in the assessment was requested individually. The participants of the alternative measures group were selected from the groups of psychological intervention of Alternatives Measures in the first session, before beginning therapy. This group was collectively informed about the goals of the investigation, their participation was requested, and subsequently, individual assessment was carried out. Data collection began with the review of the case files; subsequently, the diagnostic interview SCID-II was carried out and finally the participants completed the self-reports in the presence of the investigator.

The research design met the ethical standards and code of behavior of the American Psychological Association (2002, 2010): contribution of benefits, without causing any harm; professional responsibility and confidentiality; personal integrity, without resorting to deception; justice and equity in benefit of the contributions; and respect for the person's dignity, without excluding any collective of persons from the benefits. These criteria are met in this study, as it is carried out by means of questionnaires that do not cause any harm, with prior information about the study, and requesting authorization by means of informed consent. The conclusions will provide preventive information and data to improve the treatment of PV, with benefits for society in general.

Data analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis by means of contingency tables and chi-square tests to estimate the association between qualitative variables, as well as central tendency indexes (e.g., mean, standard deviation), and Student's t for the difference of means. Subsequently, these variables were incorporated into the binary logistic regression analysis, using the forward stepwise procedure based on the Wald statistic. The effect sizes were estimated with phi, Cramer's V, and the Odds Ratio (OR).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The results of the sociodemographic variables showed that the probability of being sentenced to prison was significantly greater, χ2(1, N = 90) = 9.23, p < .01, α = .32, for the Spaniards (.652) than for the other nationalities (.292); and that the offenders who had no professional qualification (.613) had a significantly higher probability of being sentenced to prison, χ2(1, N = 90) = 4.76, p < .05, α = .26, than those who were qualified (.267). In the remaining sociodemographic variables, there were no differences between inmates with prison sentences and community sentences (see Table 1). As for the whole population, it is noteworthy that half (.489) came from a deficient socio-economic family level, Z(N = 90) = -0.21, ns; were (.544) economically deficient or need aid, Z(N = 90) = -0.75, ns; were unstable jobs, either with or without aid, Z(N = 90) = -0.75, ns; and suffered from a stressful life situation, Z(N = 90) = -1.732, ns. Finally, more than half (.700) had a deficient educational level, that is, with only primary studies or incomplete primary studies, Z(N = 90) = 3.77, p < .001.

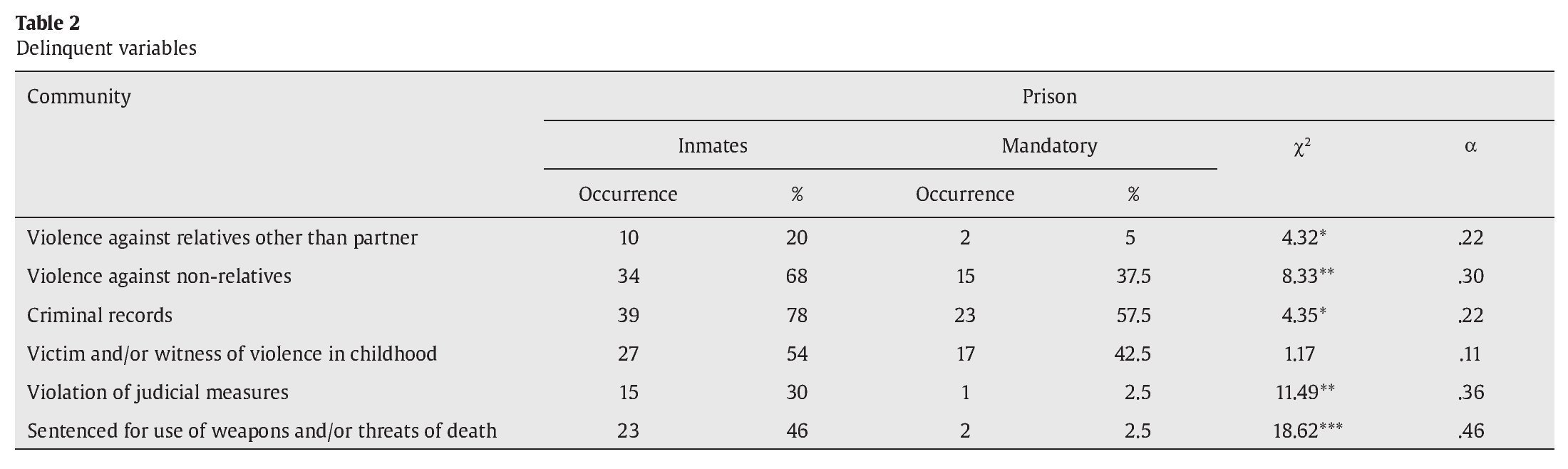

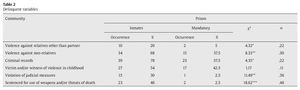

Of the delinquent indicators assessed, significant differences were observed in five of them, with a higher presence in the prison inmate group (see Table 2). Thus, they were more sentenced because of the use of weapons and/or threats of death (PI: 46% vs. MCIP: 2.5%). Likewise, they violated more frequently the judicial measures, such as restraining orders or conditional freedom (PI: 30% vs. MCIP: 2.5%) and were sentenced more frequently because of the use of violence against non-relatives (PI: 68% vs. MCIP: 37.5%). Lastly, significant differences were found in violence against relatives other than the partner, (PI: 20% vs. MCIP: 5%) and criminal records (PI: 78% vs. MCIP: 57.5%).

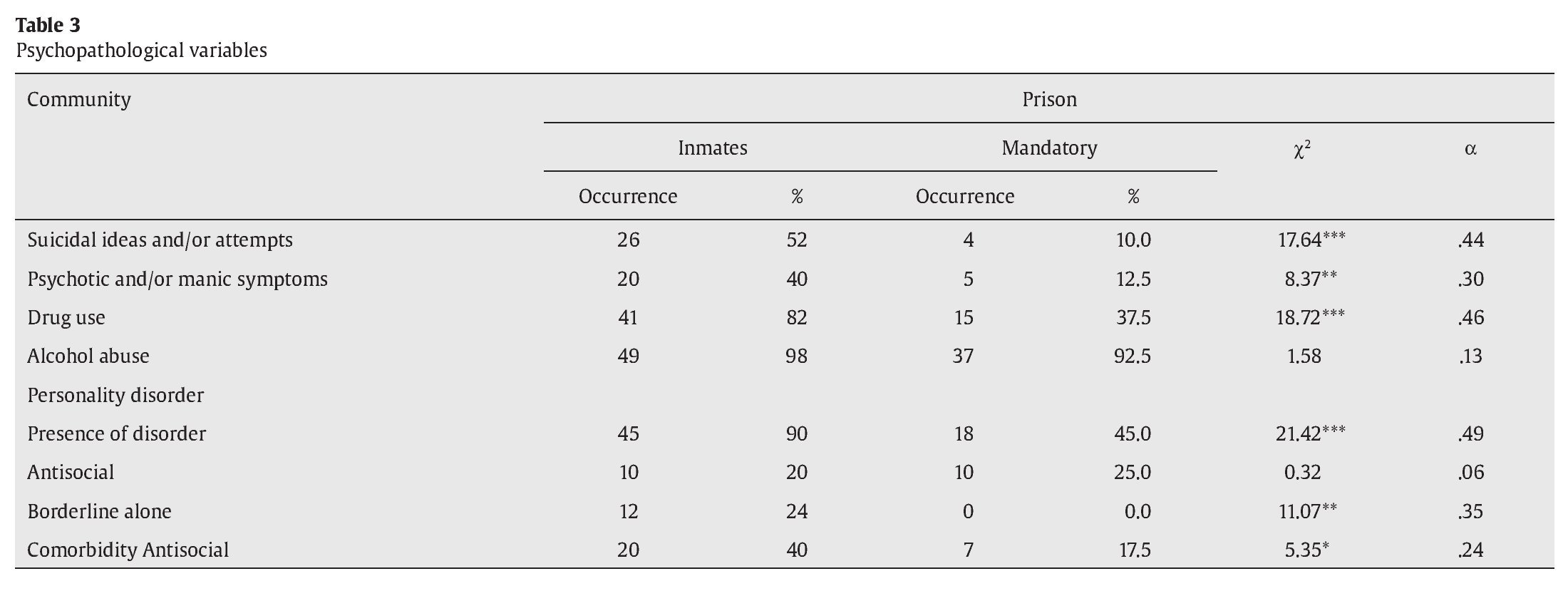

Table 3 shows the values of the psychopathological indicators, including the personality disorders assessed, through their presence/ absence and their diverse comorbidities. Suicide ideas and/or attempts were statistically significant and more present among prison inmates (PI: 52% vs. MCIP: 10%). Psychotic and/or manic symptoms were unequally present in the two groups, with 40% in the prison inmates and 12.5% in the mandatory community. Drug use had a high and significant incidence among prison inmates (PI: 82% vs. MCIP: 37.5%). In contrast, abusive alcohol consumption presented no differences, being present in almost all the participants of both groups (PI: 98% vs. MCIP: 92.5%).

Regarding the results of the personality disorders (see Table 3), results showed that the prison inmates were significantly more diagnosed as personality disorders (PI: 90% vs. MCIP: 45%), as Borderline disorder without associated disorders (PI: 24% vs. MCIP: 0%), and as comorbid of antisocial disorder with other personality disorders (PI: 40% vs. MCIP: 17.5%). No differences were observed between groups in the isolated diagnosis of antisocial disorder (PI: 20% vs. MCIP: 25%). Nevertheless, the high prevalence of this diagnosis in both groups is noteworthy. The results of passive-aggressive disorder were excluded from the statistical analyses due to its low incidence.

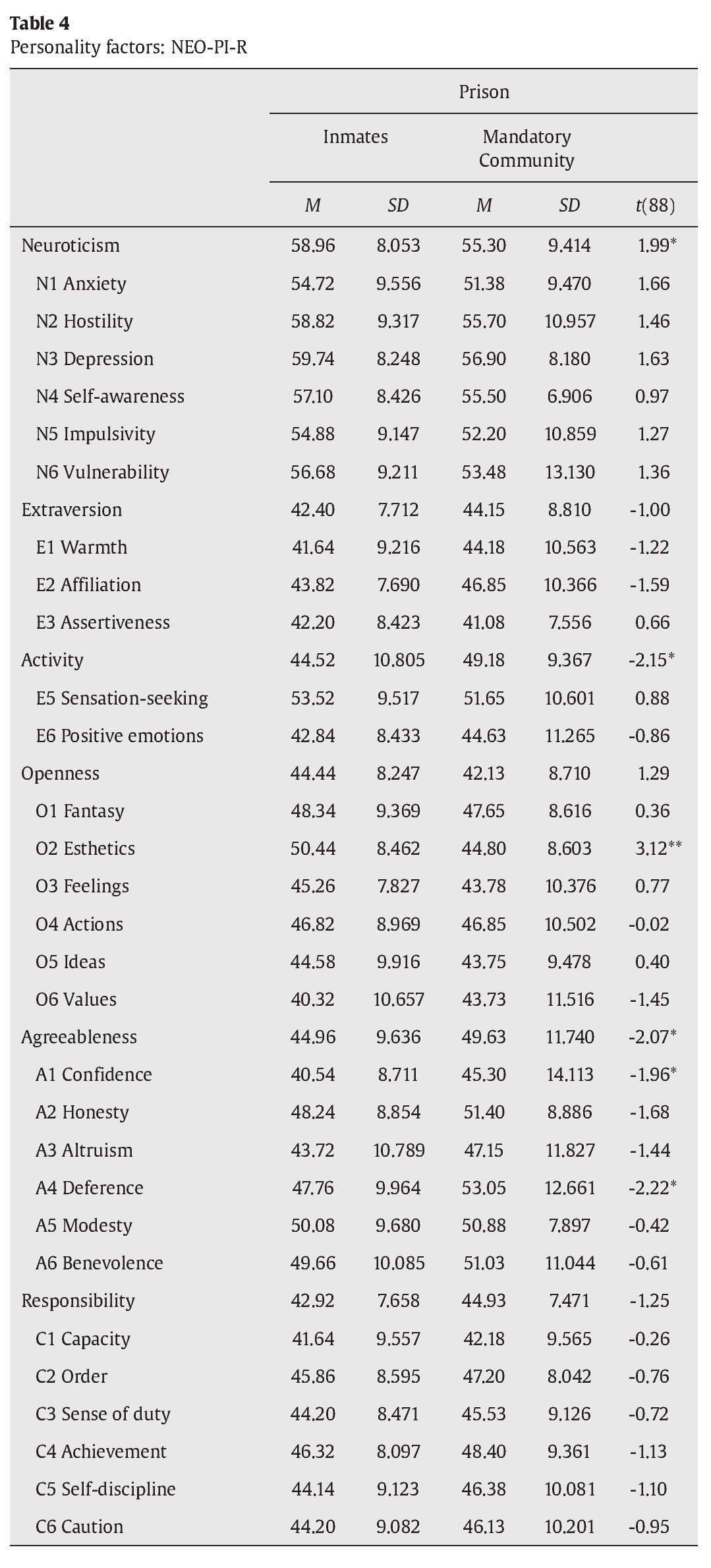

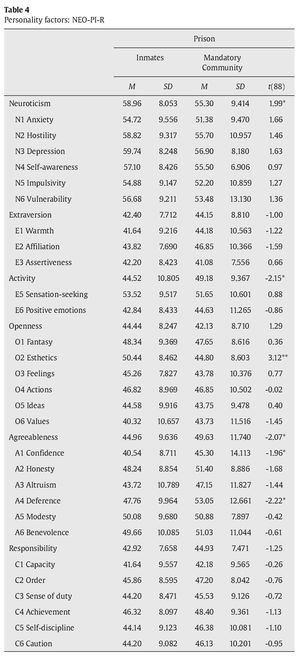

Regarding the study of the non-pathological personality carried out with the NEO-PI-R (Table 4), we only found significant differences in the domain of Agreeableness (PI: M = 44.96 vs. MCIP: M = 49.63), t(88) = -2.07, p < .05, Cohen's d = -0.43. The domain of Neuroticism was also with significant differences (PI: M = 58.96 vs. MCIP: M = 55.30), t(88) = 1.99, p < .05, Cohen's d = 0.41.

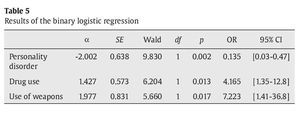

Logistic Regression Analysis

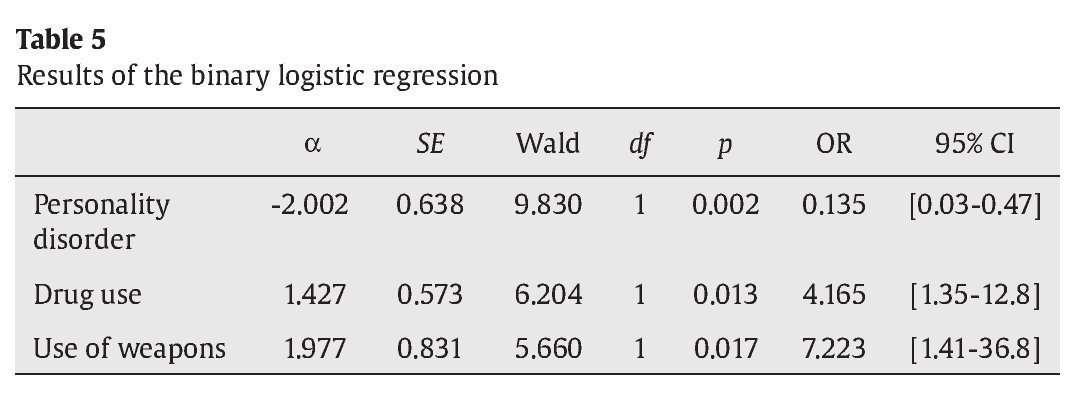

In order to identify the defining indicators and/or variables of the members of each subsample we performed a forward stepwise logistic regression with the stepwise procedure. This analysis introduced the significant variables, in the steps followed by the models, obtaining Nagelkerke's R2 of .501 as a fit value. The model used three steps, definitely introducing three variables in the equation: personality disorder, drug use, and use of weapons. This model correctly classified 78.9% of the cases (χ2 = 42.21, p < .001), defining these three variables as central to assign a participant to a certain group. The odds ratios obtained by the model show the probabilities associated with being a prison inmate for each variable, if the subject had that characteristic (see Table 5). The use of weapons and/or threats of death multiplied by 7 the probability of belonging to the group of prison inmates, that is, of being sentenced to prison instead of to an alternative measure. Drug use increased the likelihood of belonging to this group by four and lastly, with the lowest OR of all three variables, the presence of a personality disorder increased the probability of belonging to the group of prison inmates by .135. A higher probability of belonging to the group of prison inmates means that these factors increase the aggressor's possibilities of committing more serious crimes.

Discussion

As a global conclusion of this study, with regard to the proposed goals, the group of aggressors incarcerated for PV generally present greater alteration in the target variables of the study than the group of aggressors sentenced to alternative measures. However, we identified the final logistic regression model by selecting three variables: use of weapons, drug use, and diagnosis of personality disorder. The presence of these variables in the aggressor increases the probability of belonging to the group of prison inmates, that is, of committing more serious aggressions. These results complement the diverse studies of the etiological factors of PV, in contrast to risk variables in the aggressor, as a function of the dangerousness of the violent acts committed (Cavanaugh & Gelles, 2005). Likewise, it has allowed us to identify delinquent variables, which, although noteworthy in the group of prison inmates, are more relevant in the mandatory community, mainly concerning penal records and exerting violence. Another goal addressed is the study of non-pathological personality and personality disorders, and we obtained higher incidence than other studies, providing results to reflect on the diagnostic method.

Specifically, we shall comment on some group differences with regard to the socioeconomic, delinquent, and psychopathological indicators.

Socio-economic Variables

In this section, the indicators of occupational qualification and nationality are those that best differentiate the groups. The prison inmates' low occupational qualification could be related to their scarce academic and economic levels, considering both the aggressor and his family of origin. Such economic and occupational instability would facilitate situations of stress, hindering the adequate solution of interpersonal conflicts, such as with the partner, as indicated by the functional models (Bell & Naugle, 2008; Capaldi et al., 2012; Stith et al., 2004; Stuart, 2005).

Regarding nationality, we observed greater presence of foreigners, mainly Latin Americans, in the group of alternative measures. In Spain, we have a population of 11% of aliens (Secretaría de Estado de Inmigración y Emigración, 2011), similar to the percentage identified in the prison inmate group, in contrast to the group of alternative measures, where one half of the convicts were foreign. These data show that foreigners do not commit more dangerous acts than nationals, presenting the same risk level, as the percentage of foreigners sentenced to prison is the same as in society. This fact is an interesting contribution of our study, taking into account that in other studies more risk is attributed to men from Latin American or African American cultures, but without specifying the level of severity of the aggression (Stith et al., 2004). However, a possible explanation of the higher percentage of Latin Americans who commit low-risk PV, generating sentences to alternative measures, may be found in the cultural influence of how they relate to their partners (Echauri, Fernández-Montalvo, Martínez, & Azcárate, 2013; Fernández-Montalvo, Echauri, Martínez, & Azcárate, 2011). The Latin American culture facilitates learning attitudes that favor this type of violence, blaming the victims to a greater extent, and the social environment hinders filing official complaints and breaking up this type of violent relation (Gracia, Herrero, Lila, & Fuente, 2009, 2010).

Delinquent Variables

In this second series of variables, the results show that the prison inmates present a delinquent career with more criminal records and judicial violations (conditional freedom and restraining orders) and greater use of violence in diverse settings, including the family. It is noted that these characteristics are included in the different prediction guides of the risk of delinquent recidivism (Campbell, 1995; Echeburúa, Amor, Loinaz, & Corral, 2010; Hilton et al., 2004; Kropp, Hart, Webster, & Eaves, 1999). It is notable that more than one half of the men sentenced to alternative measures present criminal or police records, indicating that it was not an isolated delinquent act, and that perhaps the alternative measure is not sufficient to put a stop to this criminal trajectory, as such antecedents are considered to be indicators of maintaining this type of violent behavior (Menéndez et al., 2013).

Within the delinquent risk factors, the "use of weapons and/or believable threats of death" was one of the factors selected by the logistic regression model. This factor increases by 7 the probability of belonging to the group of prison inmates, that is, of being sentenced to prison, and is the indicator with the greatest discriminant power. Obviously, the use of weapons increases the harmful capacity of the aggressor, which is a determinant of a sentence of privation of freedom. This result coincides with the different scales used to predict future violent behaviors, which assign a high risk of recidivism to this factor.

Psychopathological Variables

The group of prison inmates was noteworthy because they presented greater psychopathological alteration than the group of alternative measures, especially in the variables identified by the final model: drug use and diagnosis of personality disorder. In our study, drug use in prison inmates was much higher than that observed in national and international studies, habitually between 13 and 35% (Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Loinaz, Echeburúa, & Torrubia, 2010; Stith et al., 2004). These differences were also found in abusive alcohol consumption (Huss & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2006). A possible explanation of the high incidence found in our study may be due to the mixed method used for data collection, interview versus supervision of case files. This method is recommended in a population with high social desirability, such as the penitentiary population, providing greater reliability by contrasting the information and supervising the different case files (Gortner, Gollan, & Jacobson, 1997; Heise & Garcia-Moreno, 2003).

Drug use usually provokes a pronounced lack of behavioral control, with impulsive responses and cognitive distortions. When these circumstances coincide with the existence of cultural beliefs and negative attitudes towards women, such as men's feelings of superiority, the probability of PV increases (Eckhardt, Samper, Suhr, & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2012). We think that this collective's high levels of drug use suggest the need for a double therapeutic approach, a specific one for PV (pathological jealousy, attitudes against women, impulsive responses, etc.), and a treatment for addictive behaviors (Easton et al., 2007). Likewise, we think that preventive measures should be adopted in sensitive collectives, such as those sentenced to alternative measures, taking into account the result of the logistic regression model obtained in our study, showing that drug use multiplies by four the possibilities of belonging to the group of prison inmates. This fact would justify reviewing the therapeutic programs used in alternative measures, adapting the programs to the characteristics of the aggressors, and specifically including an adequate preventive approach to drugs (Arias et al., 2013).

Personality disorder is another variable identified by the model, and its presence in the aggressor increases the possibility of being sentenced to prison, that is, of committing higher risk aggressions. The high rates of these disorders, especially in the prison inmates, which were higher than in other studies (Boira & Jodrá, 2010; Echauri et al., 2011; Fernández-Montalvo & Echeburúa, 2008; Gondolf, 1999; Hart, Dutton, & Newlove, 1993), may be due to the diagnostic tool used, as we used the clinical interview to the detriment of self-reports because of the characteristics of the penitentiary population, following the recommendations of various authors (Dutton, 2003). Another interesting finding is the distribution of the disorders in the subsamples: antisocial disorder was similar in both groups; borderline disorder was diagnosed mainly in the group of prison inmates; passive-aggressive disorder was scarce in the entire sample. Comorbidity should also considered, as the comorbidity of antisocial disorder with the other two disorders was noteworthy in the group of prison inmates. This aspect was not reported in other studies and it should be taken into account in the typologies of aggressors (Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994) and in the design and application of the intervention programs (Amor et al., 2009; Arias et al., 2013; Feder & Wilson, 2005).

In this block of psychopathological variables, we also underline the results obtained in "suicidal ideas and/or attempts" because more than one half of the prison inmates suffer from this, and these results are much higher than those of other studies (Loinaz et al., 2010). In view of the high rates of sentences for PV in Spain, the suicide prevention program implemented in prisons is very important, as these aggressors are considered to have a sensitive profile (Dirección General de Instituciones Penitenciarias, 2005).

These results are consistent with theories underlining the level of psychopathological impairment of the aggressors at higher risk, because their characteristics, such as abusive drug and alcohol consumption, violent behaviors, and personality disorders, hinder treatment (Hilton, Harris, Rice, Houghton, & Eke, 2008).

Non-pathological Personality Characteristics

The results obtained in non-pathological personality reveal that the prison inmates are characterized by lower Agreeability and higher Neuroticism; also, although without significant differences, they had lower mean values in Responsibility and Extroversion and higher values in Openness. These results are consistent with their higher tendency towards antisocial behavior and neurotic symptomatology, such as anxiety, depression, or hostility. Along with these people's impulsivity and greater need for experiences, such tendencies have generated legal problems and finally led to their incarceration.

Limitations

We wish to present the main limitations of this investigation, focusing particularly on the sample size. A more extensive sample in future studies would ratify whether the mixed methodology to measure variables, with supervision of case files and the clinical interview as the diagnostic instrument of personality disorders, is more reliable than self-reports. Regarding the sample, another proposal is to expand the study of these common factors to other criminal typologies, such as common delinquents or sexual aggressors, identifying the differences with partner aggressors. The results obtained for personality disorders, with a clear difference between the two groups, suggest that in future studies the typologies of aggressors should be identified as a function of their provenance, prison or alternative measures, due to its therapeutic impact (Arce & Fariña, 2010). Another aspect concerning psychopathological characteristics is to expand the investigation to the diagnosis of psychopathy because of the results found in the prison inmates, who had a high incidence in factors denoting psychopathic tendencies, with scarce empathy or emotional coldness, such as the case of violence towards relatives (Fernández-Montalvo & Echeburúa, 2008; Hare, 2002). Lastly, it would be interesting to address the specific risk factors for PV after describing the common factors, such as type of aggression employed, chauvinistic attitudes, and attitudes favoring violence against women, jealousy, and characteristics of the partner relationship, among others (Cattlet, Toews, & Walilko, 2010; Cunradi, Ames, & Moore, 2008).

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Manuscript received: 10/12/2013

Revision received: 10/04/2014

Accepted: 31/06/2014

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to José Antonio Ruiz.

Facultad de Psicología. Área de Psicología Social.

E-30100 Murcia, Spain.

E-mail: jaruiz@um.es

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.06.003

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-text revision (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. American Psychologist, 57, 1060-1073. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.57.12.1060

American Psychological Association (2010). Amendments to the 2002 "Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct". American Psychologist, 65, 493. doi: 10.1037/a0020168

Amor, P. J., Echeburúa, E., & Loinaz, I. (2009). ¿Se puede establecer una clasificación tipológica de los hombres violentos contra su pareja? [Can a typological classification of violent men against their partner be established?]. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 9, 519-539.

Arce, R., & Fariña, F. (2010). Diseño e implementación del Programa Galicia de Reeducación de Maltratadores: Una respuesta psicosocial a una necesidad social y penitenciaria [Design and implementation of the Galician Program for batterers' reeducation: A psychosocial response to a social and penitentiary need]. Intervención Psicosocial, 19, 153-166. doi: 10.5093/in2010v19n2a7

Arias, E., Arce, R., & Vilariño, M. (2013). Batterer intervention programmes: A meta-analytic review of effectiveness. Psychosocial Intervention, 22, 153-160. doi: http:// dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2013a18

Arribas, D. (1999) Inventario de Personalidad NEO Revisado (NEO-PI-R) e Inventario NEO Reducido de Cinco Factores (NEO-FFI) [Revised NEO Personality Inventory - NEO-PI-R - and NEO Inventory Reduced to Five Factors - NEO-FFI]. Madrid: TEA Ediciones.

Babcock, J. C., Green, C. E., & Robie, C. (2004). Does batterers' treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1023-1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001

Belfrage, H., & Rying, M. (2004). Characteristics of spousal homicide perpetrators: A study of all cases of spousal homicide in Sweden 1990-1999. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 14, 121-133. doi: 10.1002/cbm.577

Bell, K., & Naugle, A. (2008). Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1096-1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.003

Boira, S., & Jodrá, P. (2010). Psicopatología, características de la violencia y abandonos en programas para hombres violentos con la pareja: resultados en un dispositivo de intervención [Psychopathology, characteristics of violence and dropout in male batterers treatment programs: Results of an intervention service]. Psicothema, 22, 593-599.

Caetano, R., Vaeth, P., & Ramisetty-Milker, S. (2008). Intimate partner violence victim and perpetrator characteristics among couples in the United States. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 507-518. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9178-3

Campbell, J. C. (1995). Assessing dangerousness. Violence by sexual offenders, batterers, and child abusers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Capildi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3, 231-280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231

Casares-López, M. J., González-Menéndez, A., Torres-Lobo, M., Secades-Villa, R., Fernández-Hermida, J. R., & Álvarez, M. M. (2010). Comparación del perfil psicopatológico y adictivo de dos muestras de adictos en tratamiento: En prisión y en comunidad terapéutica [Comparison of psychopathological and addictive profile in two samples of addicts in treatment: Prison and therapeutic community]. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 10, 225-243.

Cattlet, B. S., Toews, M. L., & Walilko, V. (2010). Men gendered constructions of intimate partner violence as predictors of court-mandated batterer treatment drop out. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 107-123. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9292-2

Cavanaugh, M. M., & Gelles, R. J. (2005). The utility of male domestic violence offender typologies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 155-166.

Contreras, L., Molina V., & Cano, M.C. (2011). In search of psychosocial variables linked to the recidivism in young offenders. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 3, 77-88.

Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1992). The Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO-Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Cunradi, C. B., Ames, G. M., & Moore, R. S. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence among a sample of construction industry workers. Journal of Family Violence, 23, 101-112. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9131-x

Dirección General de Instituciones Penitenciarias (2005). Instrucción 14/2005: Programa marco de prevención de suicidios [Instruction 14/2005: Framework Program on suicide prevention]. Retrieved from http://institucionpenitenciaria.es/web/export/ sites/default/datos/descargables/instruccionesCirculares/c-2005-14.pdf

Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. (1984). The nature and antecedents of violent events. British Journal of Criminology, 24, 269-288.

Dutton, D. G. (1995). The batterer: A psychological profile. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Dutton, D. (2003). MCMI Results for batterers: A response to Gondolf. Journal of Family Violence, 18, 253-255.

Easton, C. J., Mandel, D. L., Hunkele, K. A., Nich, C., Rounsaville, B. J., & Carroll, K. M. (2007). A cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol-dependent domestic violence offenders: An integrated substance abuse-domestic violence treatment approach (SADV). American Journal on Addictions, 16, 24-31. doi: 10.1177/1524838000001002004

Echauri, J. A., Fernández-Montalvo, J., Martínez, M., & Azcárate, J. M. (2011). Trastornos de personalidad en hombres maltratadores a la pareja: Perfil diferencial entre agre-sores en prisión y agresores con suspensión de condena [Personality disorders in batterers: Differential profile between aggressors in prison and aggressors with a suspended sentence]. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 21, 97-105. doi: 10.5093/jr-2011v21a9

Echauri, J. A., Fernández-Montalvo, J., Martínez, M., & Azcárate, J. M. (2013). Effectiveness of a treatment programme for immigrants who committed gender-based violence against their partners. Psicothema, 25, 49-54. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2012.75

Echeburúa, E., Amor, P. J., Loinaz, I., & Corral P. (2010). Escala de Predicción del Riesgo de Violencia Grave contra la Pareja - Revisada - (EPV-R) [Severe Intimate Partner Violence Risk Prediction Scale-Revised (EPV-R)]. Psicothema, 22, 1054-1060.

Eckhardt, C. I., Samper, R., Suhr, L., & Holtzworth-Munroe A. (2012). Implicit attitudes toward violence among male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27, 471-491. doi: 10. 1177 / 0886260511421677

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey. Results at a glance. Retrieved from http://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/vaw-survey-results-at-a-glance

Fariña, F., Arce, R., & Buela-Casal, G. (2009). Violencia de género: Tratado psicológico y legal [Gender violence: Psychological and legal treaty]. Madrid: Editorial Biblioteca Nueva.

Feder, L., & Wilson, D. B. (2005). A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: Can courts affect abusers' behavior? Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 239-262. doi: 10.1007/s11292-005-1179-0

Fernández-Montalvo, J., & Echeburúa, E. (2008). Trastornos de personalidad y psicopatía en hombres condenados por violencia grave contra la pareja: Un estudio en las cárceles españolas [Personality disorders and psychopathy in men convicted of serious intimate partner violence: A study in Spanish prisons]. Psicothema, 20, 193-198.

Fernández-Montalvo, J., Echauri, J., Martínez, M., & Azcárate, J. M. (2011). Violencia de género e inmigración: Un estudio exploratorio del perfil diferencial de hombres maltratadores nacionales e inmigrantes [Gender violence and immigration: An exploratory study of the differential profile national and immigrant male abusers]. Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, 19, 439-452. doi: 10.5093/in2013a17

First, M., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R., Williams, J., & Smith, L. (1999). Guía del usuario para la entrevista clínica estructurada para los trastornos de la personalidad del eje II del DSM-IV [User's guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for Axis II Personality Disorders of DSM-IV]. Barcelona: Masson.

García, C., Moral, J., Frías, M., Valdivia, J., & Díaz, H. (2012). Family and socio-demographic risk factors for psychopathy among prison inmates. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 4, 119-134.

Gondolf, E. W. (1999). MCMI-III results for batterer program participants in four cities: Less "pathological" than expected. Journal of Family Violence, 14, 1-17.

Gortner, E. T., Gollan, J. K., & Jacobson, N. S. (1997). Psychological aspects of perpetrators of domestic violence and their relationships with the victims. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 337-352.

Gracia, E., Herrero, J., Lila, M., & Fuente, A. (2009). Perceived neighborhood social disorder and attitudes toward domestic violence against women among Latin American immigrants. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 1, 25-43.

Gracia, E., Herrero, J., Lila, M., & Fuente, A. (2010). Percepciones y actitudes hacia la violencia de pareja contra la mujer en inmigrantes latinoamericanos en España [Perceptions and attitudes towards partner violence against women among Latin American immigrants in Spain]. Psychosocial Intervention, 19, 135-144. doi: 10.5093/ in2010v19n2a8

Hare, R. (2002). Psychopathy and risk for recidivism and violence. In N. Gray, J. M. Laing, & L. Noaks (Eds.), Criminal justice, mental health and the politics of risk (pp. 27-47). London: Cavendish.

Hart, S. D., Dutton, D. G., & Newlove, T. (1993). The prevalence of personality disorder amongst wife assaulters. The Journal of Personality Disorders, 7, 329-341.

Heise, L., & García-Moreno, C. (2003). La violencia en la pareja [Partner violence]. In E. G. Krug, L. L. Dahlberg, J. A. Mercy, A. B. Zwi, & R. Lozano (Eds.), Informe mundial sobre violencia y salud (pp. 97-131). Washington DC: Organización Panamericana de la Salud.

Hilton, N. Z., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Houghton, R. E., & Eke, A. W. (2008). An in-depth actuarial assessment for wife assault recidivism: The domestic violence risk appraisal guide. Law and Human Behavior, 32, 150-163. doi: 10.1007/s10979-007-9088-6

Hilton, N. Z, Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Lang, C., Cormier, C. A., & Lines, K. J. (2004). A brief actuarial assessment for the prediction of wife assault recidivism: The Ontario domestic assault risk assessment. Psychological Assessment, 16, 267-275. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.267

Holtzworth-Munroe, A, & Stuart, G. (1994). Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 476-497.

Huss, M. T., & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. (2006). Assessing generalization of psycho-pathy in a clinical sample of domestic violence perpetrators. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 571-586. doi: 10.1007/s10979-006-9052-x

Kropp, P. R., Hart, S. D., Webster, C. D., & Eaves, D. (1999). Spousal assault risk assessment guide (SARA). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems.

Lila, M., García, A., & Lorenzo, M. (2010). Manual de intervención con maltratadores [Intervention with batterers. Manual]. Valencia, Spain: University of Valencia.

Lila, M., Oliver, A., Galiana, L., & Gracia, E. (2013). Predicting success indicators of an intervention programme for convicted intimate-partner violence offenders: The Contexto Programme. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 5, 73-95.

Lobbestael, J., Leurgans, M., & Amtz, A. 2010. Inter-rater reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID I) and Axis II Disorders (SCID II). Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18, 75-79. doi: 10.1002/cpp.693

Loinaz, I., Echeburúa, E., & Torrubia, R. (2010). Tipología de agresores contra la pareja en prisión [Characteristics of aggressors against women in prison]. Psicothema, 22, 106-111.

Maffei, C., Fossati, A., Agostoni, I., Barraco, A., Bagnato, M., Deborah, D., ... Petrachi, M. (1997). Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (version 2.0). Journal of Personality Disorders, 11, 279-284.

Menéndez, S., Pérez, J., & Lorence, B. (2013). La violencia de pareja contra la mujer en España: Cuantificación y caracterización del problema, las víctimas, los agresores y el contexto social y profesional [Partner violence against women in Spain: Quantification and description of the problem, the victims, the aggressors, and the social and professional context]. Psychosocial Intervention, 22, 41-53. doi: 10.2093/ in2013a6

Novo, M., Fariña, F., Seijo, M. D., & Arce, R. (2012). Assessment of a community rehabilitation programme in convicted male intimate-partner violence offenders. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12, 219-232.

Redondo, N., Graña, J. L., & González, L. (2009). Características sociodemográficas y delictivas de maltratradores en tratamiento psicológico [Sociodemographic and delinquent characteristics of batterers in treatment]. Psicopatología Clínica, Legal y Forense, 9, 49-61.

Rodríguez, F. J., Bringas, C., Rodríguez, L., López-Cepero, J., Pérez, B., & Estrada, C. (2011). Drug abuse and criminal family records in the criminal history of prisoners. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 3, 89-105.

Salize, H. J., Dressing, H., & Kief, C. (2007). Mentally disordered persons in European prison system: Needs, programmes and outcome (EUPRIS) (Final report). Manheim, Germany: Central Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2004/action1/docs/action1_2004_frep_17_en.pdf

Secretaría de Estado de Inmigración y Emigración (2011). Estadística [Statistics]. Retrieved from http://extranjeros.empleo.gob.es/es/estadisticas/

Secretaría de Estado de Instituciones Penitenciarias (2013). Estadística [Statistics]. Retrieved from http://www.institucionpenitenciaria.es/web/portal/administracion-Penitenciaria/estadisticas.html

Stith, S. M., Smith, D. B., Penn, C., Ward, D., & Tritt, D. (2004). Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10, 65-98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2003.09.001

Stuart, R. (2005). Treatment for partner abuse: Time for paradigm shift. Professional Psychology, 36, 254-263. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.254

Vicens, E., Tort, V., Dueñas, R. M., Muro, A., Pérez-Arnau, F., Arroyo, J. M., ... Sarda, P. (2011). The prevalence of mental disorders in Spanish prisons. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 21, 321-332. doi: 10.1002/cbm.815

Walker, L. E. (1984). The battered woman syndrome. New York, NY: Springer.

World Health Organization (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/violence_against_women_20130620/en/