Rape myths affect many aspects of the investigative and criminal justice systems. One such myth, the ‘real rape’ myth, states that most rapes involve a stranger using a weapon attacking a woman violently at night in an isolated, outdoor area, and that women sustain serious injuries from these attacks. The present study examined how often actual offences reported to a central UK police force over a two year period matched the ‘real rape’ myth. Out of 400 cases of rape reported, not a single incident was found with all the characteristics of the ‘real rape’ myth. The few stranger rapes that occurred had a strong link to night-time economy activities, such as the victim and offender both having visited pubs, bars, and clubs. By contrast, the majority of reported rape offences (280 cases, 70.7%) were committed by people known to the victim (e.g., domestic and acquaintance rapes), occurred inside a residence, with most victims sustaining no physical injuries from the attack. The benefits of these naturalistic findings from the field for educating people about the inaccuracy of rape myths are discussed.

Los mitos sobre la violación influyen en muchos aspectos de los sistemas judiciales de investigación y penales. Uno de esos mitos, el referido a la “violación real”, sostiene que la mayoría de las violaciones implican la participación de un extraño armado que ataca a una mujer de forma violenta durante la noche, en un lugar aislado al aire libre y que las mujeres sufren heridas graves a consecuencia de los ataques. Este estudio analizó la frecuencia con la que coincidían los delitos reales denunciados a la policía en el centro del Reino Unido con el mito de la “violación real” durante un periodo de dos años. De los 400 casos de violación denunciados, no se encontró ninguno que tuviera las características del mito de la “violación real”. Las escasas violaciones por extraños acaecidas estaban vinculadas a actividades laborales nocturnas, como que la víctima y el agresor hubieran estado en pubs, bares y clubs. Por el contrario, la mayoría de las violaciones denunciadas (280 casos, 70.7%) las cometieron personas conocidas de la víctima (por ejemplo, violaciones domésticas o por conocidos) y tenían lugar en el domicilio, sin que la mayoría de las víctimas sufrieran lesiones a consecuencia del ataque. Se comenta la utilidad de estos resultados con casos reales para instruir a la gente acerca de la inexactitud de los mitos de la violación.

Rape myths have been defined as “descriptive or prescriptive beliefs about rape (i.e., about its causes, context, consequences, perpetrators, victims, and their interaction) that serve to deny, downplay, or justify sexual violence that men commit against women” (Bohner, Eyssel, Pina, Siebler, & Tendayi Viki, 2009, p. 19). Such myths attribute blame to the victim for their rape (e.g., that women who dress scantily provoke rape), suggest that many claims of rape are false (e.g., that women often make up rape accusations in revenge against the alleged perpetrator), remove blame from the perpetrator (e.g., implying men cannot control their sex drive), and suggest that rape only happens to particular kinds of women (e.g., only women who are promiscuous get raped; Bohner et al., 2009).

Rape myths are held by people of both sexes, all ages, and across races (Burt, 1980; Johnson, Kuck, & Schander, 1997; McGee, O’Higgins, Garavan, & Conroy, 2011; Suarez & Gadalla, 2010). For example, McGee et al. (2011) found over 40% of their sample believed that rape accusations are often fabricated. They also exist in those who deal with rape cases professionally, such as police officers (Goodman-Delahunty & Graham, 2011; Page, 2007; Sleath & Bull, 2012). Such myth acceptance has been not only found for victims (Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004) but also perpetrators of sexual assault (Marshall & Hambley, 1996).

Acceptance of rape myths can have serious effects on people's behaviour and attitudes towards rape offences. Victims of rape who hold rape myths may not acknowledge their experiences as rape. Rape is legally defined in England and Wales as the intentional penetration of another person's vagina, anus, or mouth with the perpetrator's penis without consent or reasonable belief of consent (Sexual Offences Act, 2003, s.1). Peterson and Muehlenhard (2004) found that, amongst women who had had an experience that would legally be defined as rape, acceptance of specific rape myths affected whether they perceived the experience as rape or not. For example, women who had not fought their attacker and accepted the rape myth that a victim had to fight back for the offence to be classified as rape were less likely to say they had been raped, despite the fact that, legally, they had been.

Acceptance of similar myths involving a codified stereotype of a crime also affects the attitudes of police officers. In a written mock trial in which a female defendant was charged with the murder of her husband and had pleaded not guilty on the grounds of legitimate self-defence due to intimate partner violence, police officers’ opinions were affected by how prototypical the defendant was described to have been (Herrera, Valor-Segura, & Expósito, 2012). When the defendant was described as a prototypical battered woman (e.g, a shy mother who dresses poorly), she was judged as having less control over the situation than when she was described as a non-prototypical battered woman (e.g., a confident, well-dressed, businesswoman), despite no difference in the evidence against her. The police officers’ levels of sexism, empathy, their perceptions of their own personal responsibility, and of the seriousness of the crime also seem to have an effect on whether officers felt they should file a crime report, lay charges, and make an arrest in an intimate partner violence situation despite the victim's unwillingness to press charges or not (Gracia, García, & Lila, 2011; Lila, Gracia, & García, 2013). Therefore, some police officers may continue to have crime schema based on stereotypes (Goodman-Delahunty & Graham, 2011; Page, 2007; Sleath & Bull, 2012), and acceptance of these myths and the degree to which a victim, offender, and offence fits with the stereotype held may affect attitudes and behaviours towards the offence, victim, and investigation.

Rape myth acceptance has also been found to influence the reporting behaviour of victims (Du Mont, Miller, & Myhr, 2003). For instance, in the USA, Clay-Warner and McMahon-Howard (2009) found victims were twice as likely to report to the police rapes committed in public (as in the ‘real rape’ myth, discussed below) or through unlawful entry into a home as those that occurred elsewhere. They also found rapes carried out by strangers more likely to be reported than those carried out by partners or ex-partners, and that increases in reporting were associated with both the victim sustaining severe injuries (corroborated by Du Mont, Miller, & Myhr, 2003) and the use of weapons. There are a number of reasons why offences that do not fit rape myths may be reported less often; for example, victims of domestic rape may face a higher risk or fear of repeat victimisation by their partners or ex-partners which may not be the case for stranger rapes, or victims may view offences involving severe physical violence as more serious than those which are less violent. However, other reasons relate to rape myth acceptance; if victims do not interpret their experiences as rape due to their partial belief in rape myths, they may not report the rape. Biased reporting may in itself lead to perpetuation of rape myths, as more of those that fit the stereotype will be made public than those that do not fit the stereotype (McGregor, Wiebe, Marion, & Livingstone, 2000). Additionally, some victims may not actually believe in rape myths themselves, but may believe that the criminal justice system will not take their report seriously if their case does not fit with rape myths. Injured victims may have felt that this physical proof of violence (part of the ‘real rape’ myth, discussed below) corroborated their stories, and implied that their case was a ‘real’ rape case, and so the criminal justice system might take their allegations more seriously (Du Mont et al., 2003).

Rape myth acceptance relates to the perpetrating of rape and to increased self-reported rape proclivity. A number of studies using male student samples from around the world have found that increased rape myth acceptance (as measured by self-report scales) correlates with a higher likelihood of reporting that they would commit rape in a written mock date-rape scenario (Bohner et al., 1998; Chiroro, Bohner, Tendayi Viki, & Jarvis, 2004). This finding can be criticised as a hypothetical outcome in a non-criminal population. However studies with incarcerated populations have found a relationship between rape myth acceptance and the committing of actual rape offences. DeGue, DiLillo, and Scalora (2010) found that both coercive and aggressive rapists accepted rape myths to a higher degree than incarcerated men who reported having only had consensual sex. However, it is not possible to determine whether these men endorsed rape myths so strongly before they committed rape or whether their acceptance of rape myths was increased by the perpetration of the offence itself in an attempt to alleviate their guilt. Bohner et al. (1998) addressed this question by presenting a rape myth acceptance scale either before or after a written, mock date-rape scenario. They found that increased rape myth acceptance was only related to increased rape proclivity when the participants thought about rape myths before making a decision on the written date-rape scenario, whereas rape myth acceptance and rape proclivity were not related if the rape myth acceptance scale was completed after the written scenario. Bohner et al. (1998) concluded that this suggests a causal relationship between rape myth acceptance and intention to rape. However, given how pervasive rape myths are and the inconsistency of the relationship between attitudes and behaviour, it is unlikely that the accepting of rape myths of itself would lead someone to commit the offence. Instead these myths may help maintain misunderstandings regarding rape, which could affect how seriously a person would contemplate carrying out a rape.

Mock juror studies show rape myth acceptance to be associated with jurors’ opinions of victims and their judgements of guilt in simulated rape cases (Stewart & Jacquin, 2010). In studies using rape myth acceptance scales, greater endorsement of these constructs correlated with more responsibility being attributed to the victim and less to the alleged perpetrator of rape (Hammond, Berry, & Rodriguez, 2011), and lower ratings of guilt for defendants (Stewart & Jacquin, 2010). However, in a sample of real English and Welsh cases, Munro and Kelly (2009) found that those in which the victim was in a current romantic or professional relationship with the perpetrator, or where the victim and offender were friends, resulted in convictions more frequently than cases which involved different victim-offender relationships (including stranger rapes). This could be explained by these stranger rapes not fitting the ‘real rape’ myth closely enough (see below) or that rape myth acceptance may affect jurors’ opinions of the victims and perpetrators in a laboratory setting, but when exposed to a full trial, these myths have a less substantial effect on the legal outcomes.

Rape myths, therefore, can affect decisions to report, perpetrate, or convict for rape, and cause difficulties for organisations seeking to reduce the incidence of rape, increase the reporting rate, or ensure fair trials. One way of decreasing the prevalence of rape myth acceptance is education (Anderson & Whiston, 2005), which can be bolstered by empirical studies stating the true incidence of reported rapes that fit the rape myth stereotypes. Currently, there are very few published studies that have examined this and none focusing on the ‘real rape’ myth, and so the present study examined the proportion of reported rapes that correspond to the ‘real rape’ myth in a large British county. This myth maintains that ‘real rape’ (or ‘traditional’ rape as Estrich, 1986 terms it) involves a stranger attacking a victim at night in an isolated, outdoor area. The myth includes the use of extreme violence (often including the use of a weapon) and the victim strongly resisting the attack physically and sustaining injuries (Clay-Warner & McMahon-Howard, 2009; Du Mont et al., 2003). In a comparison with studies of real stranger rape cases, Sleath and Woodhams (2014) found students overestimated how frequently aspects of the ‘real rape’ myth (specifically, the violent offender and physically resistant victim behaviours) occur in rape cases. Thus, expectations of victim and offender behaviours appear to comply with the ‘real rape’ myth more than real cases of rape do.

Acceptance of rape myths has been thought to serve gender-specific functions (Bohner et al., 2009), and the notion of a ‘real rape’ myth may serve similar functions. For men who uphold such views, rape myths are thought to help self-esteem by aiding them to perceive their own acts of sexual dominance as normal and not rape, neutralising their behaviours in such a way to enable them to morally disengage and avoid perceiving themselves as violating norms of sexual behaviour (Bandura, 1999; Bohner et al., 1998). The ‘real rape’ myth does this by promoting a very narrow definition of rape. It is possible, therefore, that men who endorse this rape myth may believe that any other form of sexual aggression (for example, having sex with their partners or acquaintances without their consent, or threatening a person verbally into having sex with them) does not violate sexual norms because it does not fit the ‘real rape’ myth, and thus is not rape. For women, rape myths also affect self-esteem, but do so in relation to the likelihood of becoming a victim. Women who accept rape myths may feel protected from the risk of rape (Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2004) and feel the victim is in some way to blame for their rape due to their risky behaviour. For example, the ‘real rape’ myth may aid women in feeling safe by making them believe they are invulnerable to rape as long as they do not walk around at night alone. Acceptance of the ‘real rape’ myth may also lead to women taking fewer precautions against rape. Being less aware of situations in which they are more likely to be raped (Suarez & Gadalla, 2010), women may not avoid genuinely high risk situations.

Previous studies have examined aspects of the ‘real rape’ myth. Stranger rapes have been repeatedly found to account for less than half of all reported rape cases in studies from both the UK and the USA (Feist, Ashe, Lawrence, McPhee, & Wilson, 2007; Greenfeld, 1997; Kelly, Lovatt, & Regan, 2005; Stanko & Williams, 2009). These studies have also suggested that young women of between 16 and 29 years of age are at particular risk of rape (Feist et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2005) and that very few rapes occur outdoors (e.g., 7% and 17.3% in Feist et al., 2007 and Greenfeld, 1997, respectively). However, this finding may not be universal; Kelly et al. (2005) found 32% of rape offences were reported to have occurred in public places, but this was not further defined. The majority of rapes are reported to take place at night (Feist et al., 2007; Greenfeld, 1997). However, findings regarding victims’ sustained injuries vary significantly, with two-thirds of victims sustaining no injuries in Feist et al.’s (2007) sample, but the same proportion sustaining injuries in Kelly et al.’s (2005) sample; that both of these are reports of official statistics indicates the ambiguity in the area.

Sleath and Woodhams (2014) conducted a review of studies examining real cases of stranger rape in order to conduct a comparison with participants’ expectations of victim and offender behaviours. From their review, the frequency of different behaviours in real cases was quite variable; victims appear to physically resist their attacker (by struggling, hitting, kicking, or punching them, or trying to take the weapon away) in between 5.3% and 63.6% of cases, depending on the behaviour. Various violent offender behaviours (ripping the victim's clothes, binding or tying them up, gagging them, slapping, punching, or kicking the victim) were similarly variable (from 19.8% to 68.2% of cases). A weapon was shown to the victim in a weighted average of 42.97% of cases included in Sleath and Woodhams’ (2014) review. The presence of weapons in other samples of documented rape cases has been found to be even lower, with a mere 4% of cases involving a weapon in Feist et al.’s (2007) English and Welsh sample, compared to one in every 16 cases involving a weapon in Greenfeld's (1997) US sample. Finally, Feist et al. (2007) found alcohol consumption was commonly related to stranger rape cases, with the highest proportion of highly intoxicated victims having been attacked by a stranger. Thus, research has shown the ‘real rape’ myth to generally be an inaccurate representation of all reported rapes.

The present study examines cases reported to a UK police force over a period of two years, analyses the ‘real rape’ myth in a more typical British region than previous studies, and considers all aspects of the myth. When comparing the number of crimes committed per 1,000 population for the year ending September 2012, the county from which the current data was drawn differed on average by 0.33 to the national average (Office for National Statistics, 2012). However, London differed by 5.50, showing the county from which the current data was drawn to have crime statistics that are much more comparable to the national average than London. Additionally, this research examines not only the victim-offender relationship (e.g., stranger vs. known), but also the time of day of the offences (e.g., night-time vs. other times of the day), their location (e.g., isolated outdoor spaces vs. other locations), how offenders manipulate their victims (e.g., using force and weapons vs. alternative manipulations, such as threats), and the level of physical injuries sustained by the victim (e.g., serious injuries sustained vs. less serious or none). This was accomplished by obtaining the information regarding each of these aspects of extra-familial rape cases from official police data, as this is the primary behavioural record of the reported events.

MethodDescription of SampleAll cases of rape reported between the dates of the 1st January 2010 and 31st December 2011 were selected from the police database. Preliminary examinations of the cases revealed intra-familial cases that were removed from the dataset so as to focus specifically on extra-familial risks. All information for the remaining cases was gathered from police databases. Offences in which there were more than one victim or offender were expanded. For instance, if the police report mentioned three offenders, three cases were created in the analysis, with the details regarding one of the offenders reported in each case. This procedure led to 463 rape offence cases being identified over the two-year period.

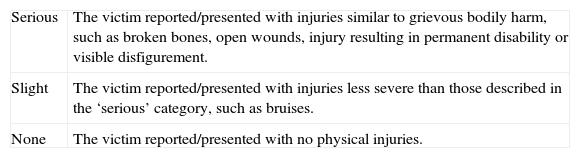

ProcedureFor each case, information was gathered regarding the victim (age, gender, and race), the offender (age, race, and prior convictions), the victim-offender relationship, and the alleged offence (location, time of offence, injuries sustained, the way the offender manipulated the victim, the investigatory outcome, and alcohol use). The categorisation of ‘injuries sustained’ came directly from the police database. These were subjective categorisations by the officer in charge of the case. However, in general, these were defined as described in Table 1.

Coding of Injuries Sustained.

| Serious | The victim reported/presented with injuries similar to grievous bodily harm, such as broken bones, open wounds, injury resulting in permanent disability or visible disfigurement. |

| Slight | The victim reported/presented with injuries less severe than those described in the ‘serious’ category, such as bruises. |

| None | The victim reported/presented with no physical injuries. |

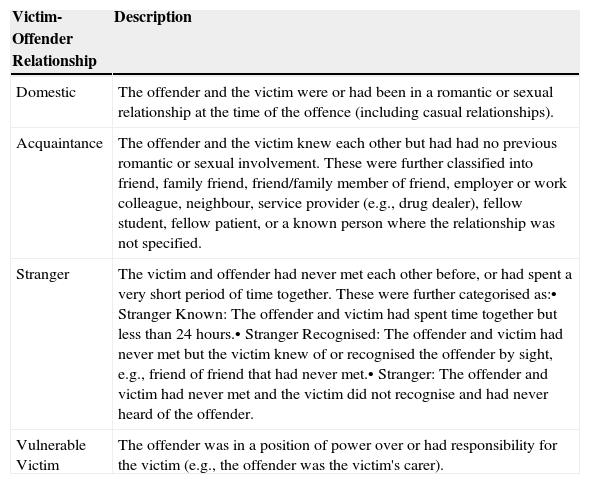

The victim-offender relationship was categorised as described in Table 2.

Coding of Victim-Offender Relationship.

| Victim-Offender Relationship | Description |

|---|---|

| Domestic | The offender and the victim were or had been in a romantic or sexual relationship at the time of the offence (including casual relationships). |

| Acquaintance | The offender and the victim knew each other but had had no previous romantic or sexual involvement. These were further classified into friend, family friend, friend/family member of friend, employer or work colleague, neighbour, service provider (e.g., drug dealer), fellow student, fellow patient, or a known person where the relationship was not specified. |

| Stranger | The victim and offender had never met each other before, or had spent a very short period of time together. These were further categorised as:• Stranger Known: The offender and victim had spent time together but less than 24hours.• Stranger Recognised: The offender and victim had never met but the victim knew of or recognised the offender by sight, e.g., friend of friend that had never met.• Stranger: The offender and victim had never met and the victim did not recognise and had never heard of the offender. |

| Vulnerable Victim | The offender was in a position of power over or had responsibility for the victim (e.g., the offender was the victim's carer). |

The majority of the information needed was available on the police force's databases. However, if necessary, a hard copy was requested, and if still not found, the officer in charge would be asked if they remembered the information (this was only reverted to if the victim-offender relationship had still not been found and this actually occurred in less than ten cases). Information which was not revealed by any of these means was coded as not reported.

ResultsRemoval of Inappropriate Cases and Case OutcomesTwenty cases involved more than one victim or more than one offender and so were expanded (as described above). Some cases (63) had been ‘cancelled’ by the police. This happened when there was significant evidence that the reported rape had not occurred (for example, if the entire event was filmed and showed the victim to be a willing participant or if the rape was reported by someone other than the victim, who then went on to deny rape having occurred). These were removed from the dataset. This resulted in 400 cases being included in the final analysis.

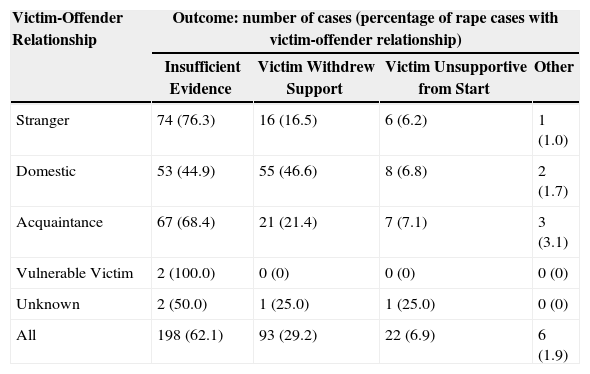

The majority of these cases remained undetected (319 cases, 79.8%) and this was mainly because the Crown Prosecution Service (the UK government department who advise the police as to whether to proceed cases to prosecution) advised not to charge the suspect due to a lack of evidence (see Table 3) or because the victim had not supported the investigation from the start or withdrew their support of the case after making the allegation. When examining only the stranger rapes, the outcomes were similar; the majority were undetected due to insufficient evidence, and in many cases the victim did not support the investigation or withdrew their support for pressing charges (see Table 3).

Victim-Offender Relationship and Outcome for Undetected Cases.

| Victim-Offender Relationship | Outcome: number of cases (percentage of rape cases with victim-offender relationship) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Evidence | Victim Withdrew Support | Victim Unsupportive from Start | Other | |

| Stranger | 74 (76.3) | 16 (16.5) | 6 (6.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Domestic | 53 (44.9) | 55 (46.6) | 8 (6.8) | 2 (1.7) |

| Acquaintance | 67 (68.4) | 21 (21.4) | 7 (7.1) | 3 (3.1) |

| Vulnerable Victim | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0 (0) |

| All | 198 (62.1) | 93 (29.2) | 22 (6.9) | 6 (1.9) |

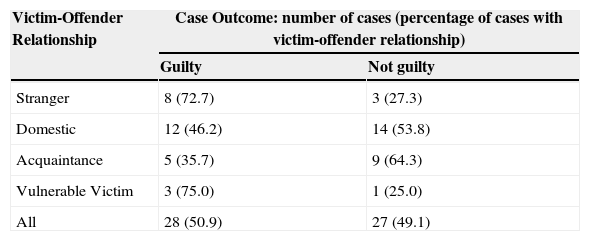

However, when a charge had been made and the outcome of the court case was known, stranger rape cases had a guilty outcome more frequently than either domestic or acquaintance rape cases (see Table 4), but this difference was not statistically significant, χ2(2)=3.55, p=.169. Only seven vulnerable victim rapes were in the dataset and thus these cases were not included in the examination of the possible effects of different victim-offender relationships.

Victim-Offender Relationship and Outcome for Completed Prosecuted Cases.

| Victim-Offender Relationship | Case Outcome: number of cases (percentage of cases with victim-offender relationship) | |

|---|---|---|

| Guilty | Not guilty | |

| Stranger | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) |

| Domestic | 12 (46.2) | 14 (53.8) |

| Acquaintance | 5 (35.7) | 9 (64.3) |

| Vulnerable Victim | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) |

| All | 28 (50.9) | 27 (49.1) |

The vast majority of victims in the sample were female (381 cases, 95.3%) and, when reported, white (345 cases, 86.3%). The victims’ race was not reported in 16 cases. A one-tailed binomial test comparing the proportion of white victims to the proportion of white people in the general population as found in the 2011 census of the county (Office for National Statistics, 2011) found no significant difference, z=-1.16, p=.14. Further one-tailed binomial tests also found no difference in the proportions of mixed race, Asian (as defined by the 2011 census, including Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Chinese and “other” Asian backgrounds), black, and “other” ethnic background victims relative to that expected from the general population, -1.25<zs<1.60, ps>.08.

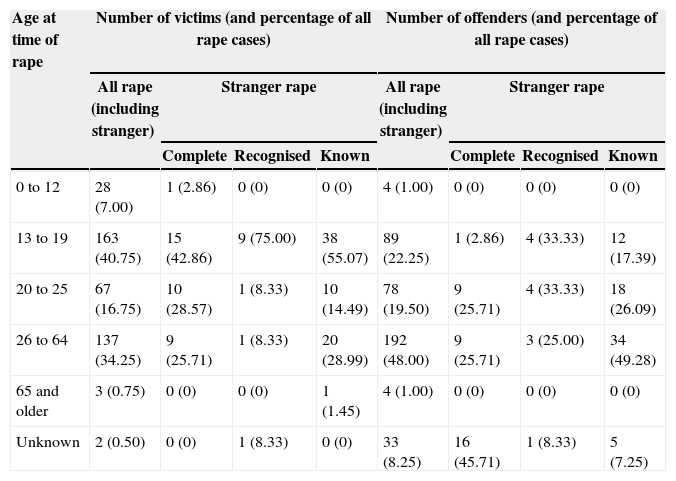

Most victims were adolescents aged between 13 and 19 (see Table 5). The victim's age was not reported in two cases. The age pattern was similar in the stranger rape cases, with 70.7% of victims being less than 25 years old. However, victims between 15 and 20 years old were particularly at risk of stranger rape (64 victims, 55.7%).

Ages of Offenders and Victims at Time of Offence.

| Age at time of rape | Number of victims (and percentage of all rape cases) | Number of offenders (and percentage of all rape cases) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All rape (including stranger) | Stranger rape | All rape (including stranger) | Stranger rape | |||||

| Complete | Recognised | Known | Complete | Recognised | Known | |||

| 0 to 12 | 28 (7.00) | 1 (2.86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 13 to 19 | 163 (40.75) | 15 (42.86) | 9 (75.00) | 38 (55.07) | 89 (22.25) | 1 (2.86) | 4 (33.33) | 12 (17.39) |

| 20 to 25 | 67 (16.75) | 10 (28.57) | 1 (8.33) | 10 (14.49) | 78 (19.50) | 9 (25.71) | 4 (33.33) | 18 (26.09) |

| 26 to 64 | 137 (34.25) | 9 (25.71) | 1 (8.33) | 20 (28.99) | 192 (48.00) | 9 (25.71) | 3 (25.00) | 34 (49.28) |

| 65 and older | 3 (0.75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.45) | 4 (1.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.50) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0) | 33 (8.25) | 16 (45.71) | 1 (8.33) | 5 (7.25) |

All offenders were male due to the definition of rape involving penetration with a perpetrator's penis (Sexual Offences Act, 2003, s.1). When recorded, the majority of offenders were white (278 cases; 75.3%; race not recorded in 31 cases). However, this is a lower proportion of white offenders than would be expected from the 2011 census (one-tailed binomial test, z=-11.13, p<.001). By contrast, there were significantly higher proportions of black (z=15.70, p<.001) and Asian (z=3.12, p=.002) offenders in the sample than would be expected from the census. In cases where both the offender and victim's race was known, the offender was at least 5.3 times (with a peak odds ratio of 38.7 for Asian offenders) more likely to attack a victim of a similar ethnic background (excluding other ethnicity as no offenders were reported with this background) than an offender of a different ethnic background was. However, offenders were most likely to have attacked a white person.

The offenders’ ages were not known in 33 cases. In cases where the offender's age was known or had been approximated by the victim, nearly half of all offenders were 25 or under (see Table 5). For stranger rapes, the offender's age was not reported in 22 cases. However, stranger rape suspects were generally older, with more than half of the offenders aged between 20 and 30 (56 offenders, 59.6%).

Time of OffenceThe exact time of the offence was not recorded for 120 cases. Of the remaining 280 offences, a large proportion were reported as having occurred at night (e.g., 118 cases were reported as occurring between 11pm and 5am, 42.1%). This was particularly true for stranger rape cases, 55.0% (60 cases) of which occurred between 11pm and 5am.

Victim-Offender RelationshipIn only four cases was it not possible to determine the relationship between the victim and the offender. Most reported rapes were carried out by men that were known to their victim (70.7%; see Table 6). Cases of domestic rape were reported most often (nearly 40%). However, in a large proportion of cases (i.e., 30.1%), the victim and offender were simply acquaintances.

Number of Rape Cases as Categorised by Victim-Offender Relationship.

| Rape type classified according to victim-offender relationship | Number of cases (and percentages) | |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic | Current partner | 95 (24.0) |

| Ex-partner | 59 (14.9) | |

| Acquaintance | Friend | 43 (10.9) |

| Friend of friend/Family of friend | 36 (9.1) | |

| Family friend | 9 (2.3) | |

| Fellow student | 8 (2.0) | |

| Employer/Work colleague | 8 (2.0) | |

| Unspecified known | 7 (1.8) | |

| Neighbour | 4 (1.0) | |

| Service provider | 4 (1.0) | |

| Stranger | Known | 69 (17.4) |

| Complete | 35 (8.8) | |

| Recognised | 12 (3.0) | |

| Vulnerable Victim | Carer/Guardian | 7 (1.8) |

Stranger rapes accounted for slightly less than a third of all reported cases. Of these stranger rape cases, the majority of victims (69 cases, 59.5%) had met the suspect socially before the offence occurred, but did not know them well (e.g., had been drinking with them prior to the attack). Some (12, 10.3%) knew of the suspect, but had not met them before (e.g., the offender was a friend of a friend that they were meeting for the first time). Less than a third (35, 30.2%) of stranger rape cases were carried out by a man whom the victim had never met before, heard of, or seen. In cases in which the victim had met the offender before but the offence was still categorised as a stranger rape, the place of initial contact between the two was frequently in a pub, club, or in the town centre generally (47 cases, 40.5%). The next most frequent meeting places were in the street (22 cases, 19%) or through friends (14 cases, 12.1%).

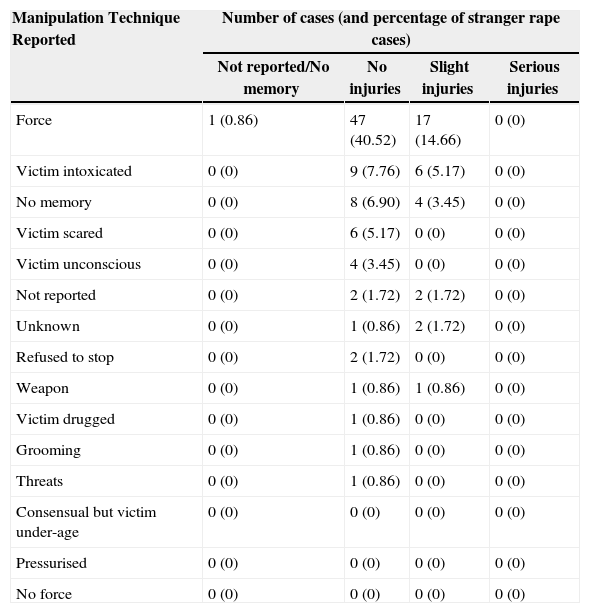

Manipulation TechniqueIn the majority of cases, the offender manipulated their victim by using force (see Table 7). However, force was defined as any physical restraint, and so ranged from pushing the victim to more harming violent acts. As can be seen by the injuries sustained by the victims (see Table 8), the majority of the cases reported involved less extreme use of force, as most victims sustained no injuries (316 cases, 79.0%). Only two victims received serious injuries, both of which were domestic incidents. Weapons were rarely reported as having been used to manipulate victims (8 cases, 2.0%). There was a significant association between the type of rape (e.g., domestic, acquaintance or stranger) and the victim sustaining slight injuries or not, χ2(2)=7.95, p=.019, with the odds ratio indicating that victims of stranger rape were twice as likely to sustain slight injuries (versus no injuries) than victims of other rape types.

Number of Rape Cases as Categorised by Manipulation Technique and Injuries Sustained.

| Manipulation technique reported | Injuries Sustained - Number of cases (and percentage of all cases) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not reported/No memory | None | Slight | Serious | |

| Force | 2 (0.5) | 163 (40.75) | 47 (11.75) | 1 (0.25) |

| Not reported | 2 (0.5) | 27 (6.75) | 3 (0.75) | 0 (0) |

| Victim unconscious | 0 (0) | 29 (7.25) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Victim scared | 0 (0) | 24 (6.0) | 5 (1.25) | 0 (0) |

| Victim intoxicated | 0 (0) | 11 (2.75) | 9 (2.25) | 0 (0) |

| No memory | 0 (0) | 13 (3.25) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Victim drugged | 1 (0.25) | 9 (2.25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Grooming | 0 (0) | 9 (2.25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weapon | 0 (0) | 5 (1.25) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.25) |

| Refused to stop | 0 (0) | 7 (1.75) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Consensual but victim under-age | 0 (0) | 6 (1.50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Threats | 0 (0) | 6 (1.50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pressurised | 0 (0) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No force | 1 (0.25) | 1 (0.25) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Number of Stranger Rape Cases as Categorised by Manipulation Technique and Victim Injuries Sustained.

| Manipulation Technique Reported | Number of cases (and percentage of stranger rape cases) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not reported/No memory | No injuries | Slight injuries | Serious injuries | |

| Force | 1 (0.86) | 47 (40.52) | 17 (14.66) | 0 (0) |

| Victim intoxicated | 0 (0) | 9 (7.76) | 6 (5.17) | 0 (0) |

| No memory | 0 (0) | 8 (6.90) | 4 (3.45) | 0 (0) |

| Victim scared | 0 (0) | 6 (5.17) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Victim unconscious | 0 (0) | 4 (3.45) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1.72) | 2 (1.72) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (0.86) | 2 (1.72) | 0 (0) |

| Refused to stop | 0 (0) | 2 (1.72) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Weapon | 0 (0) | 1 (0.86) | 1 (0.86) | 0 (0) |

| Victim drugged | 0 (0) | 1 (0.86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Grooming | 0 (0) | 1 (0.86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Threats | 0 (0) | 1 (0.86) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Consensual but victim under-age | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pressurised | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No force | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Whether the victim or offender had been drinking alcohol prior to the offence taking place was not reported in 186 (46.5%) cases. However, in the majority of cases where data on alcohol was available, both the victim and offender were reported as having drunk alcohol (104 cases, 48.6%). In 31.3% (67) of cases only the victim was reported as having drunk alcohol, whereas in 14% (30) of cases the offender was reported to have been the only one doing so prior to the offence.

In stranger rape cases, alcohol was also a significant factor. There was a statistical association between the victim being reported as drinking alone (e.g., the offender was not reported as having drunk any alcohol) and rape type (e.g., domestic, acquaintance, or stranger), χ2(2)=14.62, p=.001; odds ratio indicated the victim was 3.33 times more likely to have reported being the only one to have drunk alcohol when the offender was a stranger to them, compared to when the offender was not a stranger. Additionally, there was a significant association between the offender being reported as drinking alone and the rape type (e.g., domestic, acquaintance, or stranger), χ2(2)=17.15, p<.001. The odds ratio showed that the offender was 5.75 times more likely to have been reported as drinking alone in cases in which the offender was not a stranger to the victim compared to cases where the offender was a stranger. Additionally, offenders are reported as having been the only one drinking alcohol 4.24 times more frequently in domestic rape cases than in other rape cases. Thus, stranger rapes are associated with solely the victim drinking and rarely involve solely the offender drinking in comparison to the rapes reported with other victim-offender relationships. In contrast, domestic rapes were most likely to involve only the offender having drunk alcohol.

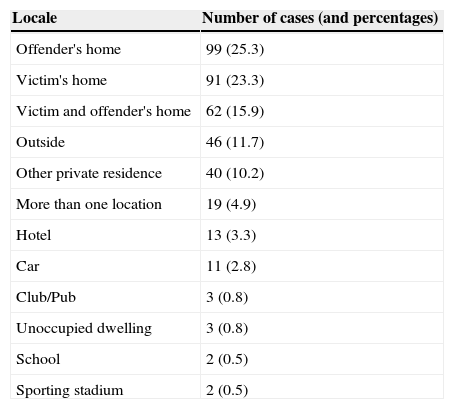

LocationMost rapes were reported to have occurred in a residence (74.7%; see Table 9), defined as someone's home (the victim's, the offender's, their shared home, or another person's, such as a friend's). Offences were reported as occurring nearly as regularly in the victim's home (23.3% of all rapes) as the offender's home (25.3%), where the majority of rapes took place.

Number of Rape Cases as Categorised by Location of Alleged Crime.

| Locale | Number of cases (and percentages) |

|---|---|

| Offender's home | 99 (25.3) |

| Victim's home | 91 (23.3) |

| Victim and offender's home | 62 (15.9) |

| Outside | 46 (11.7) |

| Other private residence | 40 (10.2) |

| More than one location | 19 (4.9) |

| Hotel | 13 (3.3) |

| Car | 11 (2.8) |

| Club/Pub | 3 (0.8) |

| Unoccupied dwelling | 3 (0.8) |

| School | 2 (0.5) |

| Sporting stadium | 2 (0.5) |

A small proportion of rapes were reported to have occurred in the open air (46 cases, 11.7%). There was a significant association between the type of rape (e.g., domestic, acquaintance, or stranger) and whether the offence occurred outside or not, χ2(2)=42.79, p<.001, with the odds ratio indicating that stranger rapes were 6.86 times more likely to occur outside than other types of rape. Stranger rapes reported to have occurred outdoors were nearly as likely to occur in woodland or park areas (13 cases), as in urban areas such as alleyways (18 cases). However, stranger rapes also often occurred in residences.

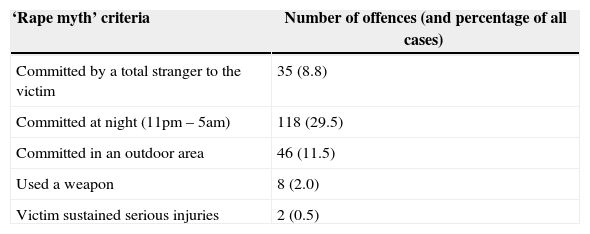

‘Real Rape’ CategoriesAll the cases were given a score out of five for how well they fit the ‘real rape’ myth. This was calculated by counting how many of the ‘real rape’ criteria (as in Table 10) applied to the case. The mean number of categories that each case had was 0.73, with a range of 0 to 4, indicating that no cases involved all aspects of the ‘real rape’ myth, and most involved one at most. However, when comparing stranger rape cases to other cases, stranger rape cases had significantly more ‘real rape’ criteria (other than the victim-offender relationship; Mdn=1) than other cases (Mdn=0), U=23,575.00, z=8.30, p<.001, r=.42. Thus, stranger rapes were more likely to include one ‘real rape’ myth criterion (other than the victim-offender relationship: e.g., to have occurred outside, or at night, or involved a weapon, or the victim to have sustained serious injuries) than acquaintance, domestic, or vulnerable victim rapes.

Number of Rapes Reported Fitting ‘Real Rape’ Myth Criteria.

| ‘Rape myth’ criteria | Number of offences (and percentage of all cases) |

|---|---|

| Committed by a total stranger to the victim | 35 (8.8) |

| Committed at night (11pm – 5am) | 118 (29.5) |

| Committed in an outdoor area | 46 (11.5) |

| Used a weapon | 8 (2.0) |

| Victim sustained serious injuries | 2 (0.5) |

These new data importantly indicate that, for this sample, cases that fit the ‘real rape’ myth are extremely rare. In fact, for the current sample, no cases involved every aspect of the ‘real rape’ myth. Only two cases in which a weapon was used were carried out by a stranger to the victim. One of these nearly fits the ‘real rape’ myth except the victim sustained slight injuries rather than serious ones. In reality, the majority of victims were attacked by someone they knew, in their own or the perpetrator's home, and, although they were often physically forced into sexual intercourse, most victims did not sustain physical injuries from the attack. These findings are very similar to previous studies’ conducted in other areas of the UK and the USA (Feist et al., 2007; Greenfeld, 1997; Kelly et al., 2005; Sleath & Woodhams, 2014; Stanko & Williams, 2009). The only aspects of the ‘real rape’ myth that were found to be accurate in the present study were the timing of the offences (typically occurring at night), and that when stranger rapes did occur, they were more likely to take place in the open-air than rapes with other victim-offender relationships. Apart from the time of the offence, the ‘real rape’ myth is a particularly inaccurate portrayal of the “average” rape reported to the police in this sample.

These new data are particularly meaningful given the previous research suggesting that rapes that fit the ‘real rape’ stereotype are more likely to be reported to the police than other rapes (Clay-Warner & McMahon-Howard, 2009; Du Mont et al., 2003). It is, therefore, likely that there are a larger number of unreported acquaintance and domestic rapes than stranger ones. Furthermore, the current study did not include intra-familial rapes. No intra-familial cases would correspond with the ‘real rape’ myth as, by definition, they involve a familial victim-offender relationship. Therefore, although the current study suffers somewhat from analysing only cases that have been reported, both unreported cases and intra-familial cases are unlikely to fit the ‘real rape’ myth, and hence would add to the large proportion of rapes that do not conform to the ‘real rape’ myth found in this study, strengthening the argument that ‘real rapes’ are very rare.

Even those cases that were categorised as stranger rapes did not fit the ‘real rape’ description. Most victims had spent some time with the perpetrator prior to the offence, thus not matching the ‘complete stranger that attacks in an alleyway’ stereotype. Frequently, the victim and offender had met in a pub, club, or in the town centre before the offence took place. This is particularly salient in conjunction with the findings related to alcohol consumption and the victims’ and offenders’ ages. Together, these new data suggest that stranger rape is strongly associated with the night-time recreational economy. That the offender meets his victim in a pub or club and that the victim has frequently been drinking suggests that these persons may be targeted because of their vulnerability following alcohol consumption. This is also supported by Feist et al. (2007), in which they found that stranger rapes were the most likely to involve a highly intoxicated victim. Victims tend to be young women and the offenders relatively young men, if slightly older than their victims (also found in Feist et al.’s (2007) sample). These women may be socially attracted to the offenders to begin with, and may be more so due to their alcohol consumption (which has been found to increase ratings of attractiveness of opposite-sex faces; Egan and Cordan, 2009; Jones, Jones, Thomas, & Piper, 2002). Additionally, due to their alcohol consumption, women may be more likely to end up in a situation where they are at risk of being raped. This may reflect differing expectations of men and women for a social evening. Men may expect sex to follow from meeting someone when they go to a pub or club, whereas women may expect to be social and friendly, but not necessarily expect sex. The myth of easy sexual availability for persons enjoying the evening entertainment economy can therefore be seen as an influence on many sexual offences.

An additional interesting finding from the present data is the relatively high number of rape cases in which the offender did not have to use force to subdue their victim. In these cases, the victim may have been targeted for having been in a state where force was unnecessary (e.g., the victim was unconscious or intoxicated), or the offender may have caused the victim to be in a state that made resistance impossible (e.g., by drugging the victim). However, in many cases, the victim reported being scared, that they felt pressurised, that they were verbally threatened, or that the offender had refused to stop. In all of these cases, no physical force was reported as being used. Thus, the reported rapes in the current sample suggest that there are a number of situations in which a victim of rape does not resist their attacker physically, either due to a physical incapacity to do so or what could possibly be a conscious decision to protect themselves from further violence. Sleath and Woodhams’ (2014) review of studies examining victims’ behaviours in stranger rape cases found women to respond by physically struggling in less than two-thirds of cases. Thus, the myth that all victims physically resist the perpetrator during a rape, which appears to be a part of the ‘real rape’ myth that many people believe, does not seem to accurately reflect a large proportion of rapes in the current sample.

Another finding from the current analysis involves the success rates of rape cases at court. The cases in which the victim and offender were strangers had a somewhat higher rate of conviction than cases with other victim-offender relationships. This may be caused by juries (or courts in some countries) using the ‘real rape’ myth in their deliberations, and so stranger rape cases, which fit the stereotype more than domestic or acquaintance rape cases, may be seen as more likely to be valid. However, in the current study this difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, this finding contradicts previous research, which has found cases with other victim-offender relationship (professional and romantic relationships and friends) to obtain successful convictions more frequently than stranger rapes or those with other victim-offender relationships (Munro & Kelly, 2009). Thus, the present study may indicate rape myths playing a part in jurors’ decision-making, as suggested by the experimental literature (Hammond et al., 2011; Stewart & Jacquin, 2010).

ImplicationsOn a practical note, there were a number of cases for which details were coded as ‘not reported’. For example, information on alcohol use was missing for nearly half of the cases in the present study. Thus, standardised reporting within the police force would be beneficial for determining the prevalence of different forms of rape and the influence of alcohol or drugs on these offences. However, the standardisation of definitions is also key. Although police officers’ reporting of injuries sustained was allocated a specific box in the database used by the police force in the current study, their definitions of ‘slight’ and ‘serious’ injuries may have varied. Standardisation within the reporting system would give a clearer idea of what types of rape are being reported and possible risk factors.

Through education and other forms of intervention, women may be made more aware of the risks that being alone with an unknown man, having drunk alcohol, entails. Social marketing interventions (such as posters placed in pubs and clubs) that both target possible victims by reminding them of the dangers of going home with a stranger and target possible offenders by informing them of the legal consequences of rape and the effect alcohol can have on a person's capacity to give consent, may decrease the incidence of these types of rape. Similar interventions have been shown to be effective in instigating behaviour change in a number of public health areas (Stead, Gordon, Angus, & McDermott, 2007).

Further education (possibly through schools and colleges that young women attend) is also necessary, especially for women who accept the ‘real rape’ myth. Such women may be particularly at risk because they may believe that they are not the kind of person to become a victim of rape, and so be less aware of the risks that are involved in being alone with unknown men. These educational programmes, however, should not be limited to young women. Debunking the ‘real rape’ myth may be useful for decreasing rape myth acceptance in men who may go on to commit rape offences, and members of the public who may be involved in making court decisions regarding rape cases. Additionally, as recommended by Herrera et al. (2012), education on myths regarding violent acts (both rape and intimate partner violence) may have positive effects on police attitudes towards these crimes and the way they are subsequently dealt with by the police.

Another form of education which may be helpful for court outcomes is the use of empirical studies similar to the current one in expert witness’ testimony. Ellison and Munro (2009) and Sleath and Woodhams (2014) advocate this form of education as a way of dispelling myths that jurors may hold that may affect their attitudes towards the defendant and the victim, and thus possibly their verdict. The present study strengthens the argument that the ‘real rape’ myth is a particularly inaccurate depiction of rapes reported in the UK and thus could help dispel these myths in jurors’ minds via expert witness testimony in rape trials.

LimitationsThe present study has a number of limitations. Firstly, its generalisability may be affected by the cases coming from a single UK police force. However, in comparison with other studies conducted in different countries and time periods, the proportion of stranger rape cases is similar (amalgamating their stranger and ‘known for less than 24 hours’ categories). For example, Feist et al. (2007), Stanko and Williams (2009), and Kelly et al. (2005) found proportions of stranger rape in their UK samples of 27.2%, 26%, and 39% respectively. In Greenfeld's (1997) US study, he found approximately a third of rape cases with victims aged 18 to 29 were perpetrated by strangers to the victim. These similarities suggest that the patterns discussed in the present study (i.e., our finding of 29.2% stranger rape cases) are not unique to this sample. Secondly, the present findings may only apply to cases actually reported to the police. For example, the over-representation of ethnic minorities in the offender sample may reflect previous studies’ findings that show cases in which the offender was of an ethnic minority background to be more likely to be reported to police than when both the offender and victim were white (Clay-Warner & McMahon-Howard, 2009). Although this is not included in the ‘real rape’ myth as defined here, this may reflect a stereotype of rape being committed by an ethnic minority offender. Thus, this data cannot be relied upon to be an entirely accurate portrayal of the incidence of rape; instead it is an accurate portrayal of reported rape, which will include a number of biasing factors (as discussed above). Finally, the present findings relied on police records of offence details. These were generally full and thorough (with the notable exception of alcohol use), probably due to the high level of training such police interviewers mandatorily receive nowadays in England. Nevertheless, even trained officers believe in some rape myths (Sleath & Bull, 2012), which may have biased what information was collected and recorded on the database. Some of the elements of rape offences discussed here were not reported in a standardised manner (e.g., information regarding manipulation was drawn from written descriptions of interviews, or initial complaints rather than being included in the reporting database consistently). Thus, police officers’ bias could easily have affected the reporting of aspects of the ‘real rape’ myth discussed here. However, any effects of these would be likely to make the present findings an overestimation of the similarity between the ‘real rape’ myth and genuine rape offences, rather than an underestimation.

Further ResearchTo address the limitations discussed, further research is key. It would be beneficial to conduct further studies of reported rape cases worldwide to determine when women are most at risk of rape and what can be done to stop these offences occurring. Studies addressing the use of alcohol and its relationship with the different victim-offender relationships in reported rape cases would also be worthwhile. If, in larger datasets with more consistent reporting of alcohol use, stranger rapes continue to be related to the victim having drunk alcohol and the offender not having done so, then social marketing and school-based education regarding the risk for women and the consequences for men should be put in place nationwide. Finally, the police force discussed in the current study put in place a poster campaign as recommended in the present study. It focused on educating men regarding the capability of drunk women to give consent for sex and the legal consequences of rape. An evaluative study examining cases since the introduction of this preventative action would be very valuable for determining its effect on behaviour change.

In conclusion, despite possible biasing behaviour at both the victims’ and the police officers’ reporting phases, no incidence of cases that fit the ‘real rape’ myth entirely were discovered in the current sample. In fact, the ‘real rape’ myth is a particularly inaccurate description of the current sample other than that the majority of offences occurred at night. Disseminating the data included in this and similar studies to the public through school education and expert witnesses may be a crucial step towards dispelling the ‘real rape’ myth, which has been shown to affect the criminal justice systems in crucial and diverse ways. It is hoped that making both possible offenders and victims aware of the greater likelihood of domestic and acquaintance rape, and stranger rape through the night-time economy, would decrease the incidence of rape offences worldwide.

Conflict of InterestThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Professor Ray Bull, Dr. Rachel Wilcock and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier draft of this article. The authors would also like to thank the police for their help during the data collection stage.