El profesorado universitario conforma una de las figuras principales en el proceso de convergencia europea, pero se desconoce cuál es su actitud hacia la reforma de los estudios universitarios en España. Por ello, el objetivo del presente estudio es evaluar la satisfacción del profesorado de la rama de Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas ante la implantación del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior (EEES). La muestra estuvo compuesta por 3.068 profesores pertenecientes a universidades públicas españolas, que imparten docencia en titulaciones de dicha rama. Se aplicó un cuestionario online, elaborado ad hoc que consta de preguntas relacionadas con el EEES, tareas y formación del profesorado, así como aspectos relacionados con la metodología y el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje, entre otros. El coeficiente alfa de Cronbach fue de ,81. Es un estudio descriptivo de poblaciones mediante encuesta con muestra probabilística, de tipo transversal. En los resultados se observa que sólo el 9,3% de los profesores está satisfecho con la forma en la que se está desarrollando la adaptación de la educación superior al EEES. Finalmente, se realiza una reflexión sobre las limitaciones que encuentra el profesorado para lograr la consolidación de este proceso.

University teachers are one of the main figures in the European convergence process, but their attitude towards the reform of Spanish university studies is unknown. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the satisfaction of Social and Legal Sciences teachers towards the introduction of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). The sample was made up of 3,068 teachers from Spanish public universities, who teach in the said field. An online questionnaire was created for this purpose, with questions relating to the EHEA, teacher tasks and training, as well as aspects related to methodology and the teaching and learning process, amongst others. Cronbach´s alpha coefficient was .81. It is a population-based, descriptive study using a cross-sectional survey with a probability sample. In the results it can be observed that only 9.3% of teachers are satisfied with the adaptation of higher education to the EHEA. Finally, the limitations faced by teaching staff in consolidating this process will be discussed.

The European Higher Education Area (EHEA) was formed in 1999 in order to achieve quality in European Higher Education and create a knowledge-based economy. Mobility is one of the main objectives of this process. Therefore, university rankings comparing institutions are useful for students and teachers while planning stays abroad, both for training and research purposes (Bengoetxea & Buela-Casal, 2013).

The latest study regarding trends in European Higher Education shows that the main reforms employed in Spain are on track to achieving greater autonomy and guaranteeing quality, as well as making changes in the introduction of new cycles and in the credit system, amongst others (European University Association, 2010). Therefore, Spain's evolution towards the new model throughout the transitional decade has been analyzed in several studies (Aghion, Dewatripont, Hoxby, Mas-Colell, & Sapir, 2008; Ariza, Bermúdez, Quevedo-Blasco, & Buela-Casal, 2012; European Commission, 2008a, 2008b). However, there are also limitations when trying to achieve total convergence between countries, especially in aspects related to doctoral studies (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Bermúdez, & Buela-Casal, 2012, 2013). Not only have there been changes in Higher Education, but also in research. The European Research Area (ERA), a strategy introduced at the Lisbon European Council (2000), was established to strengthen research in Europe and contribute in the development of a knowledge-based economy.

A new educational paradigm has emerged alongside the EHEA process (De Miguel, 2006) for which the people involved in this process must be prepared. This has led to the transformation of university education, but it is unknown if this approach is really being carried out in day to day practice and the opinion of one of the main figures participating in this process, that is, the teaching staff.

Job satisfaction in the education field offers benefits for the people involved, improves educational quality and increases the prestige of educational institutions (Anaya & Suárez, 2007). According to Monereo (2010a) there is a certain reluctance to change amongst part of Spanish university teachers, and therefore it is difficult to say if they are really taking on the new role in the classroom. The cost of modifying teaching methods could explain the resistance of some teachers towards this change (Monereo, 2010b). Fernández, Carballo and Galán (2010) stated that it is necessary for teachers to accept the change and have a positive attitude towards Spain's adaptation to the EHEA.

Despite the fact that there are studies analyzing the opinion of teachers regarding the quality of Higher Education and EHEA adaptation, as well as their satisfaction before consolidation (Cardona, Barrenetxea, Mijangos, & Olaskoaga, 2009; Ferrer i Julià, 2004), a more current assessment of European convergence is necessary. Knowing the satisfaction and teaching experience surrounding this process is vital as this is a historical event in Europe in the education field. Therefore, the aim of this investigation is to analyze the satisfaction of Spanish Social and Legal Sciences teachers after the introduction of the EHEA. This was also done recently in a study evaluating the satisfaction of Health Sciences teachers towards European convergence (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro, & Bermúdez, 2013). This way the strengths can be analyzed and also possible aspects that could limit teachers in their involvement in European convergence.

Method

Participants

The sample was made up of 3,068 teachers from Spanish public universities (both permanent non permanent members of staff) in the Social and Legal Sciences field.

Materials

- Survey regarding the Satisfaction of Spanish University Teachers towards the introduction of the EHEA, created ad hoc (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al., 2013). It has 65 mixed questions, organized in blocks with i) personal and professional information, ii) general and institutional aspects of the EHEA, iii) teaching, research and management, iv) methodology and the teaching and learning process, v) student assessment, vi) teacher training, vii) coordination, organization and resources and viii) comments and additional suggestions. Cronbach´s alpha coefficient was .81.

- Data base with the emails of teaching staff.

- It application designed for the study in order to send and apply the survey, as well as collecting results.

Design and Procedure

It is a population-based, descriptive study using a cross-sectional survey with a probability sample. The article was written following the patterns and recommendations proposed by Hartley (2012).

Firstly, a questionnaire was created for this purpose, regarding the satisfaction of teachers towards the introduction of the EHEA, which was checked by experts with experience in university teaching and in the adaptation of old degree certificates to the EHEA. After assessment and following the recommendations of the experts, some items of the questionnaire were re-written, maintaining the same number of questions as the previous version. A sample selection was then carried out amongst Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers, with a 97% confidence level (3% estimation error). Teachers were sent an invitation to participate in the study and they could access the questionnaire through an electronic link using their own password (to avoid that one person answer the questionnaire more than once), so the whole process was carried out in an individual and anonymous manner. The Spanish Personal Data Protection Act was also upheld and data confidentiality was guaranteed.

Results

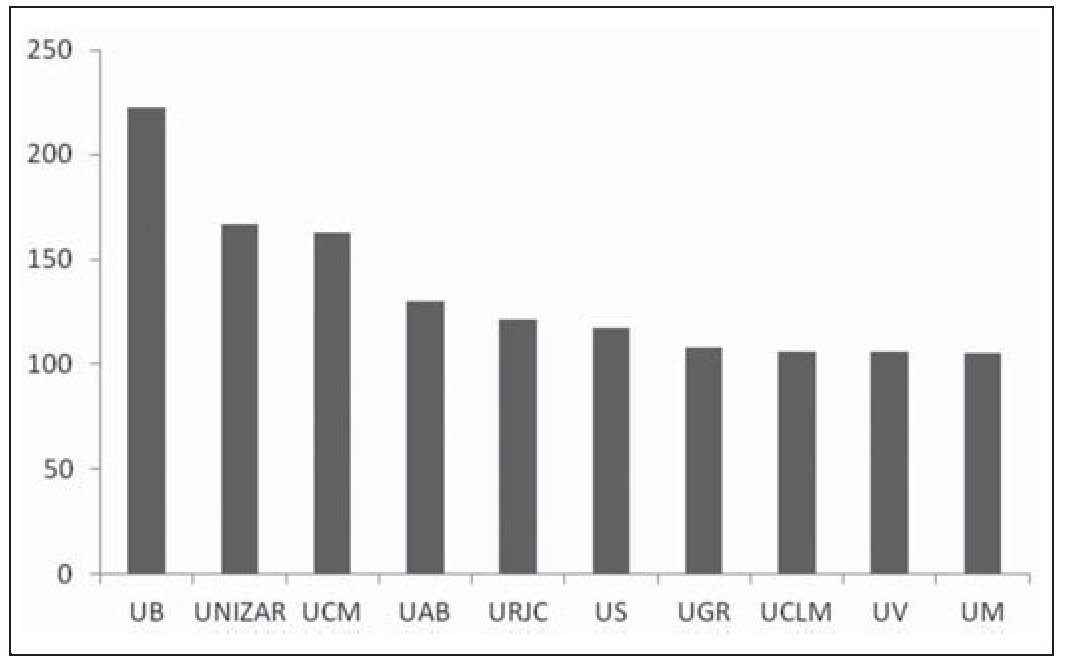

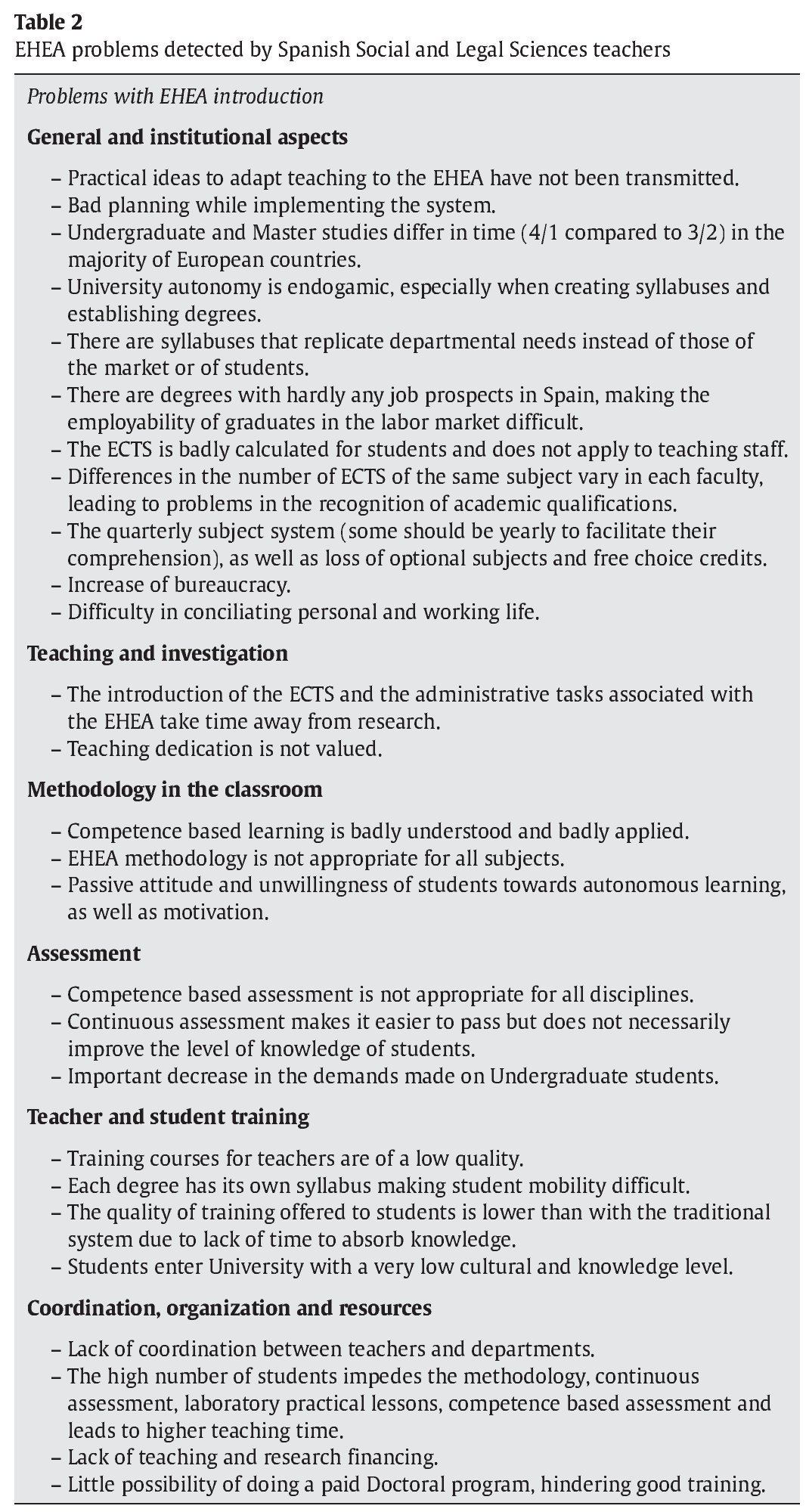

The questionnaire was answered by 3,068 Spanish public university teachers, with an average age of 46.2 (SD = 9.0), of which 52.1% are male and 47.8% female. Of the total, 58.4% were permanent members of staff, mainly senior staff members (37.9%), and the rest non permanent members of staff. The teachers surveyed have been teaching for 17.2 years on average (SD = 9.7) and 51.1% have carried out at least one research period. In Figure 1 you can see the ten universities with the highest participation of teachers in the study.

Figure 1. The ten Spanish public universities with the highest number of teachers participating in the survey. Note. UB= University of Barcelona; UNIZAR= University of Zaragoza; UCM= Complutense University of Madrid; UAB= Autonomous University of Barcelona; URJC= University Rey Juan Carlos; US= University of Seville; UGR= University of Granada; UCLM= University of Castilla-La Mancha; UV= University of Valencia; UM= University of Murcia.

General and Institutional Information

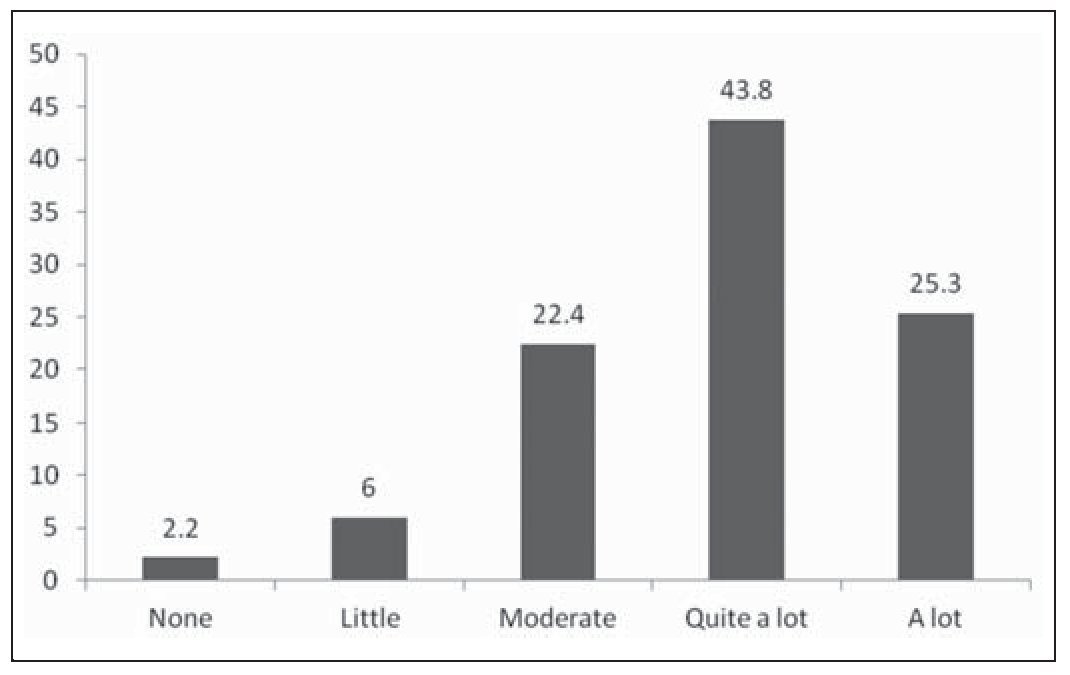

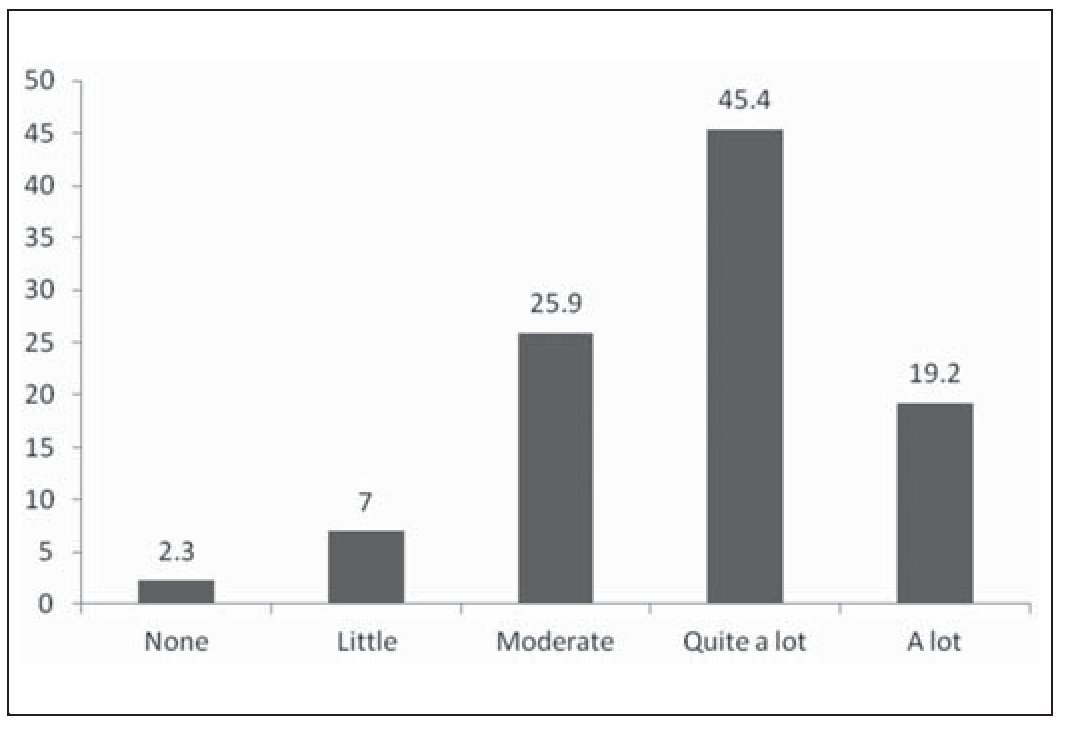

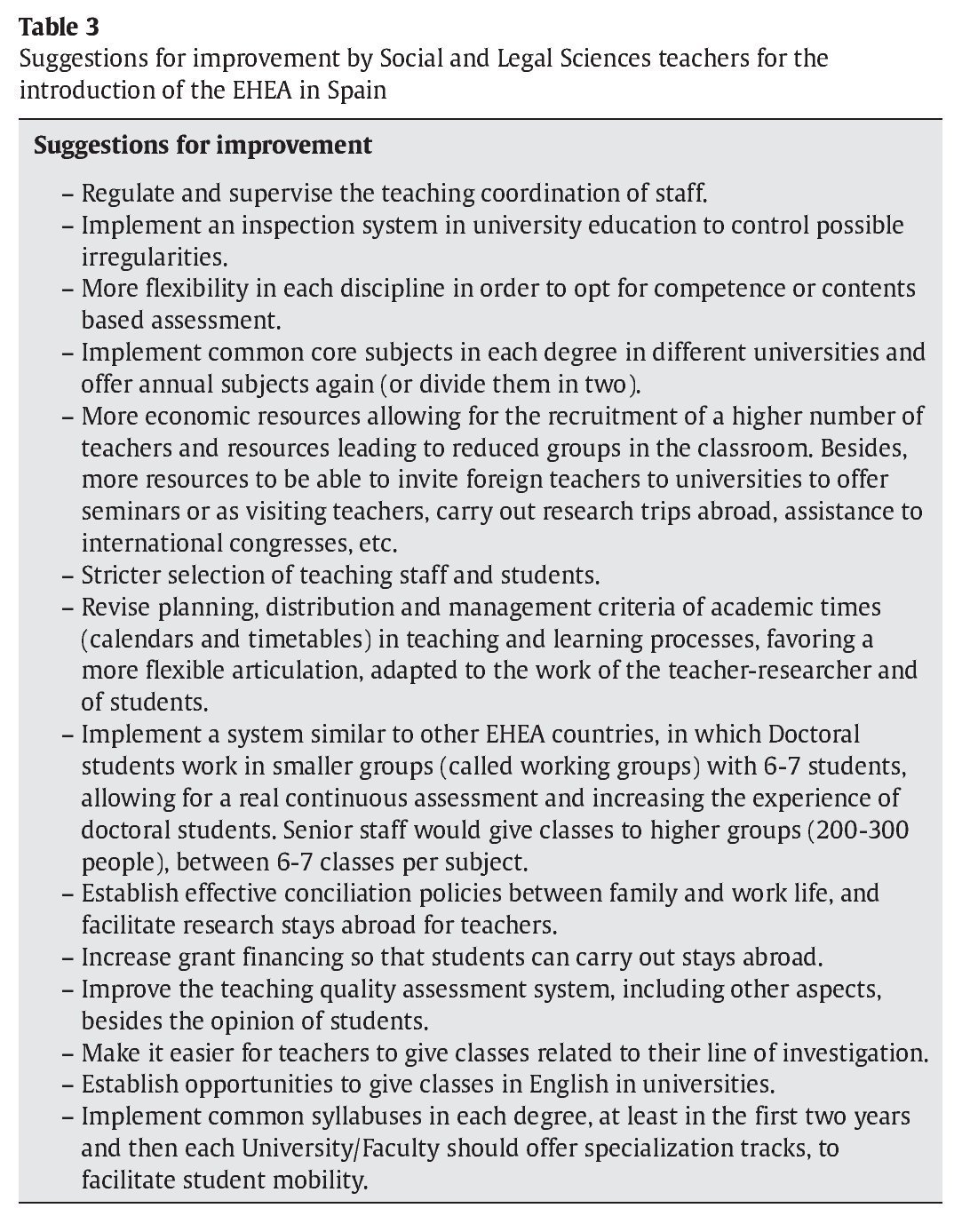

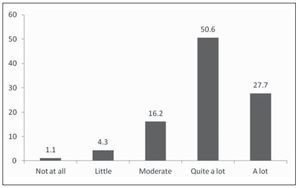

Of the teachers surveyed, 45.9% thought that the EHEA adaptation process in Spanish Higher Education is not being implemented correctly, both in structure, as in organization and methodology, followed very closely by teachers who considered that it could improve (43.1%). Only a small percentage (9.3%) believed it is being implemented correctly. Likewise, 49.4% doubted that these changes will produce positive effects in university education, 26.7% thought that they will not be positive compared to 22.7% who considered that they will. Regarding the adaptation of lesson plans to the EHEA, 43.8% of the total stated that it has taken quite a lot of effort (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to level of effort in adapting classes to the EHEA.

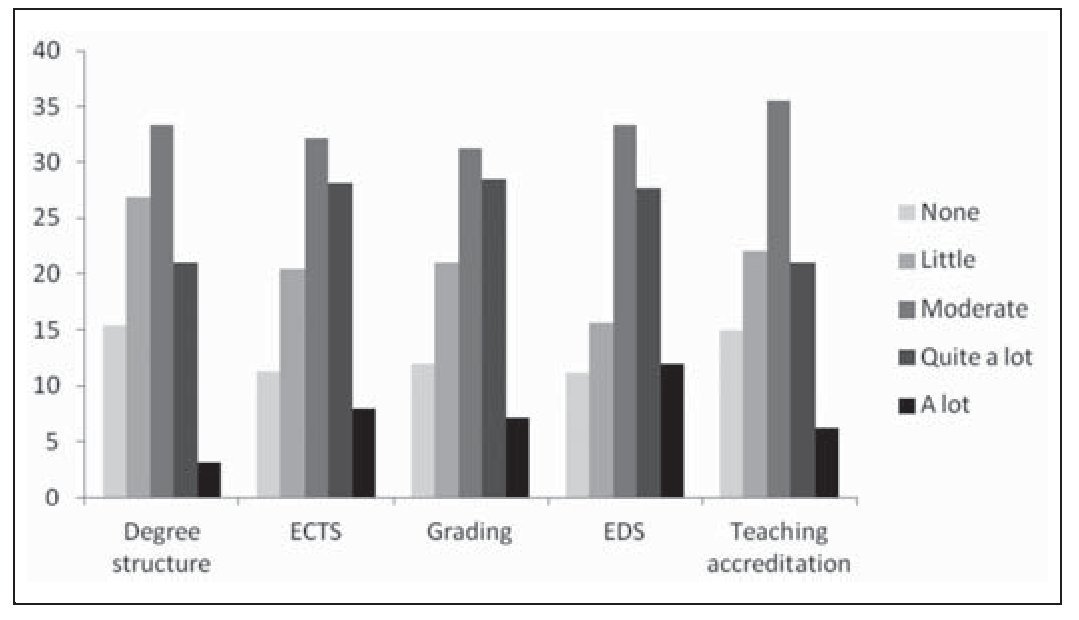

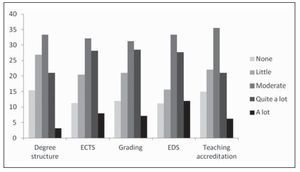

Out of the total number of teachers, 58.2% felt prepared for the change and found it easy to adapt to the EHEA system and 17.5% were more satisfied with study organization before the reform. The change was not noticed by 14.5% because they started working after the EHEA had already been introduced in the university. In general, the majority of teachers felt moderate satisfaction towards certain EHEA changes (see Figure 3), such as degree structure (33.4%), the credit system (32.1%), the grading system (31.2%), the European Diploma Supplement (33.4%) and teaching accreditation (35.6%). A very small percentage of teachers expressed a high level of satisfaction towards these changes. Specifically, the European Diploma Supplement highly satisfied 12% of those surveyed, followed by the credit system (7.9%).

Figure 3. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to satisfaction with certain aspects related to the EHEA. Note. ECTS= European Credit Transfer System; EDS= European Diploma Supplement.

Regarding the possibility of returning to the old system 48.2% would not go back, compared to 36.4% that would. A small percentage did not know how to answer (15.3%). In total, 31.6% stated that the quality of Higher Education will improve moderately; 28.5% thought that it will improve very little and 21% considered that it won't improve at all. A small percentage believed that the quality of university education will improve quite a lot (16.5%) or a lot (2.1%), becoming more efficient and effective.

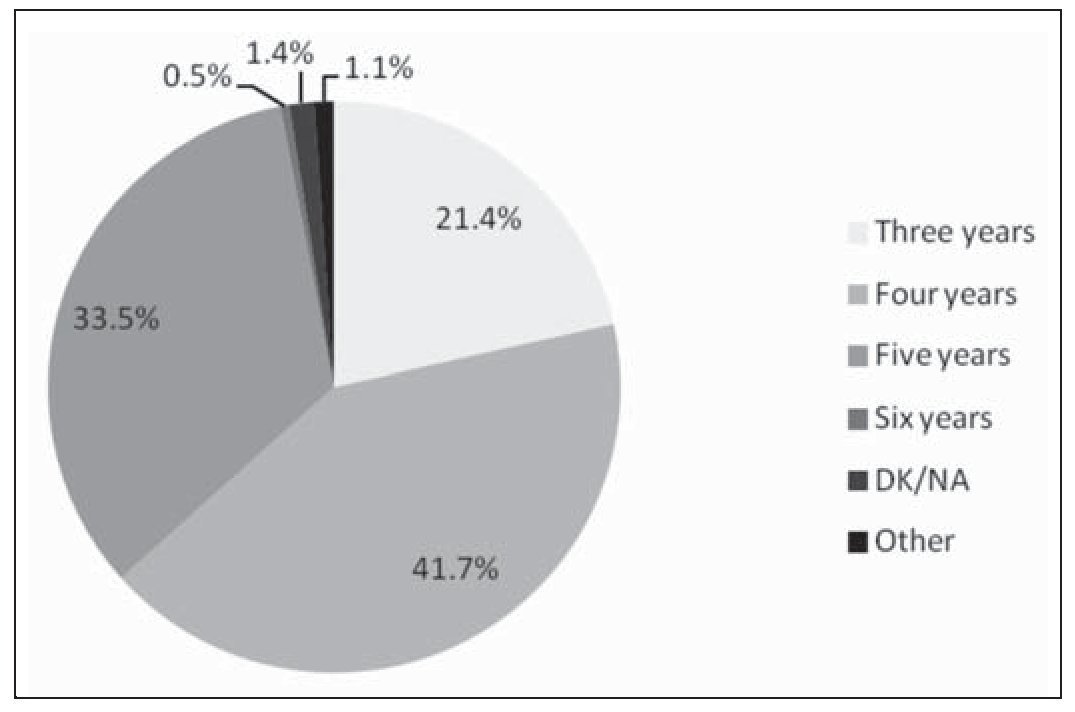

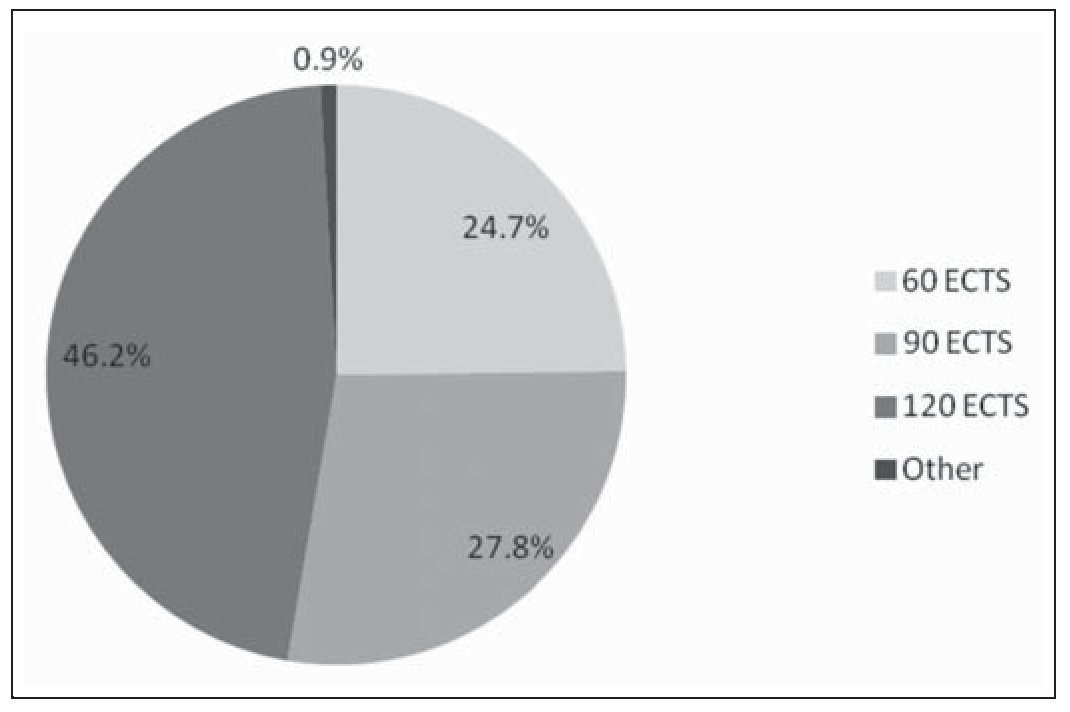

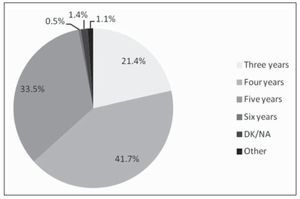

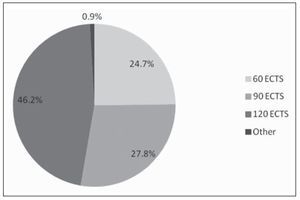

In Figure 4 the time considered necessary to carry out Undergraduate studies can be seen. The majority thought that four years is adequate (41.7%), followed by those considering that five years is more appropriate (33.5%) and 1.1% stated that it should depend on the degree, amongst other aspects. In Figure 5 it is shown that for Masters Degrees, 46.2% would prefer a length of two years (120 ECTS) and 0.9% would prefer a different length, stating that it should depend on the content of the Master or the duration of Undergraduate studies.

Figure 4. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the duration considered most appropriate for Undergraduate studies.

Figure 5. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the duration considered most appropriate for Master studies.

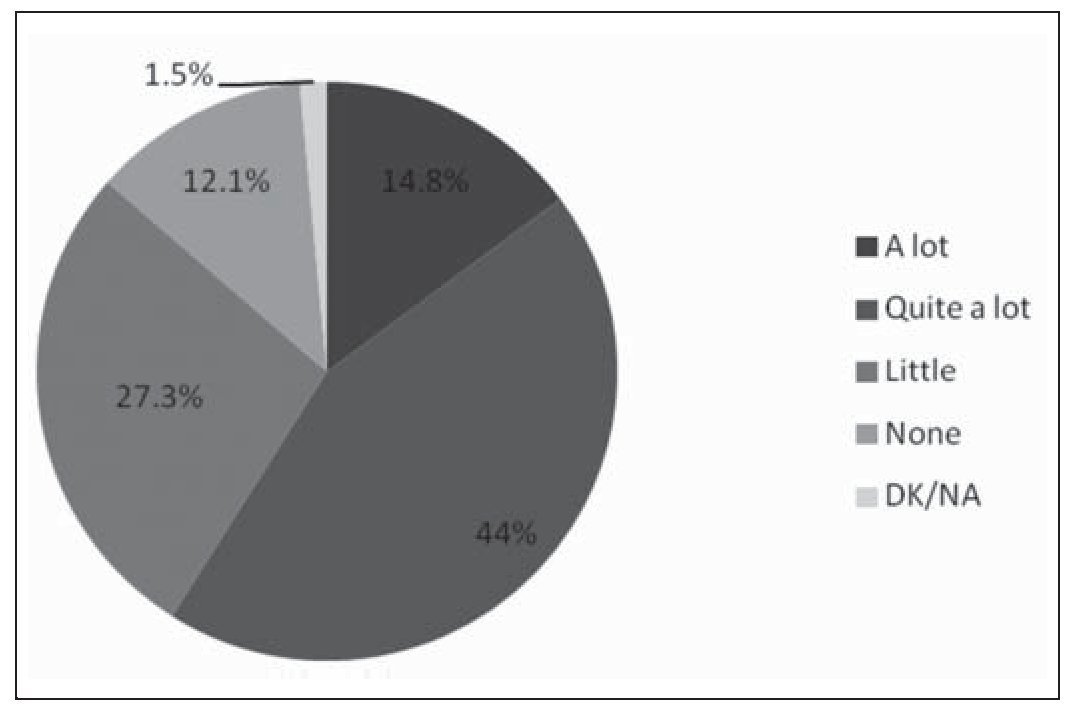

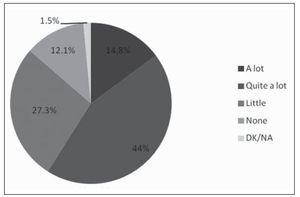

Regarding the amount of information received by teachers while adapting their subjects to the EHEA, the majority stated that they received quite a lot (44%) (see Figure 6). Likewise, 61.3% declared that there are collaboration plans with teachers for EHEA adaptation in their centers or universities. However, 20% did not know of the existence of any plan and 18.6% reported that no such plan exists.

Figure 6. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the amount of information received regarding the EHEA.

Teaching, Research and Management

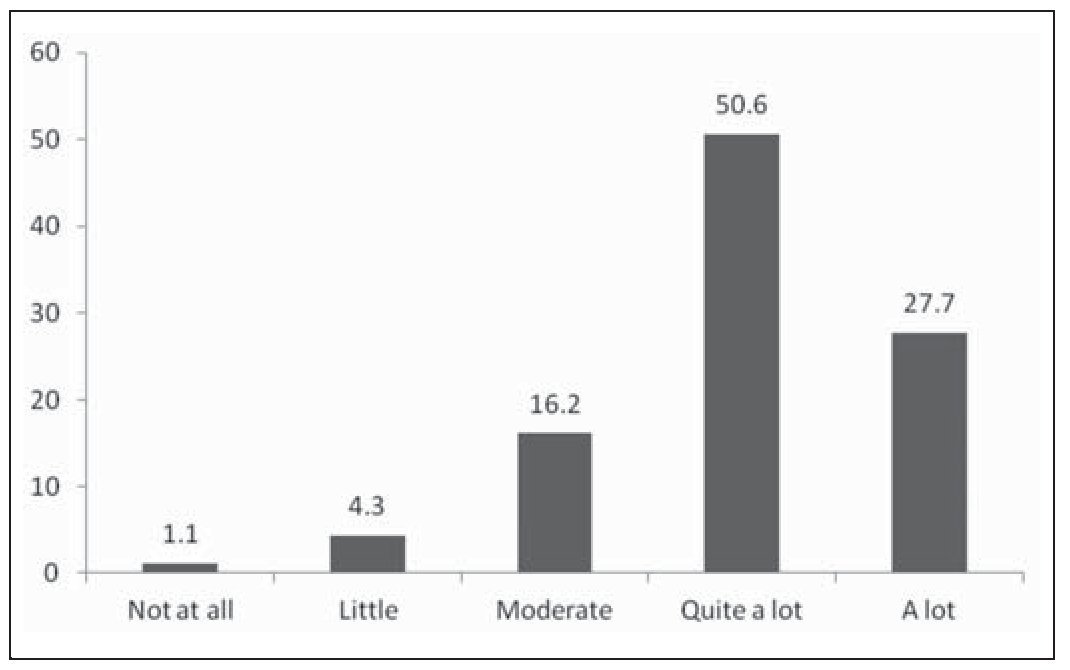

Of the total number of teachers, 50.6% affirmed that their teaching plan is quite well adapted to the EHEA (see Figure 7) and 29.9% maintained that they now need more time to prepare classes than with the old system.

Figure 7. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the adjustment level of their teaching plan to the EHEA.

One of the questions put to teaching staff was related to the level of effort needed to carry out some of their tasks as teachers. Student assessment has taken a lot of effort for the majority of teachers (39.3%), quite a lot of effort to organize and implement practical classes (34.5%), act as mediators between knowledge and students (34.6%), conducting seminars (32%), orientating and supervising students (31.8%) and teaching coordination (32.3%). Organizing and teaching theory classes took moderate effort (33.6%) and carrying out tutorials (29.8%).

In total, 60.3% had a positive vision of the ERA and 49.5% stated that, since incorporation in the EHEA, they would like to be able to spend more time on research. With regard to what they consider the most appropriate way to follow doctoral studies for student's training, 34.5% chose the new Postgraduate program, following a period of Master studies and another of Doctoral studies. 27.1% opted for the traditional Doctoral studies and 19.6% do not have enough information about the new structure to judge. The majority of teachers preferred the traditional doctoral thesis (61.9%), compared to 26.3% who opted for the compilation of articles. Besides this, 51.1% thought that it is possible to complete it in three years depending on the field. However, 62.3% declared that thesis quality will not be increased with the new Doctoral studies. The majority (31.6%) were indifferent to the creation of Doctoral Schools.

Regarding the time dedicated to management related tasks since Spain's incorporation in the EHEA, 60% stated that they would like to dedicate more time to this task.

Methodology and the Learning and Teaching Process

Of all teaching staff, 63% agreed that the teacher should act as a guide or mediator in the teaching and learning process, compared to 22.3% that did not agree. However, 10.6% were indifferent to the use of this methodology in the classroom. Teaching students mainly in a traditional classroom environment was preferred by 26% of teachers, although 67% opted for the prevalence of new teaching techniques. Furthermore, besides the classroom, 63.5% of the teachers look for other environments to teach in. Besides, 44.3% thought that the new methodology arising from the influence of the EHEA will increase the quality of learning. In contrast, 42.6% did not think that this improvement will be produced.

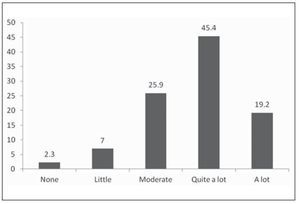

With the appearance of the competence based assessment, it is interesting to find out how much teachers develop these abilities in students. As can be seen in Figure 8, almost half of the group confirmed that students develop quite a lot of the competences required for the subject (45.4%). However, 56.8% were doubtful that the acquisition of necessary competences is guaranteed with the current Doctoral studies. Regarding the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), 78.1% stated that they use it regularly. A small percentage still uses only traditional methods (2.6%).

Figure 8. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the level of competences developped by students.

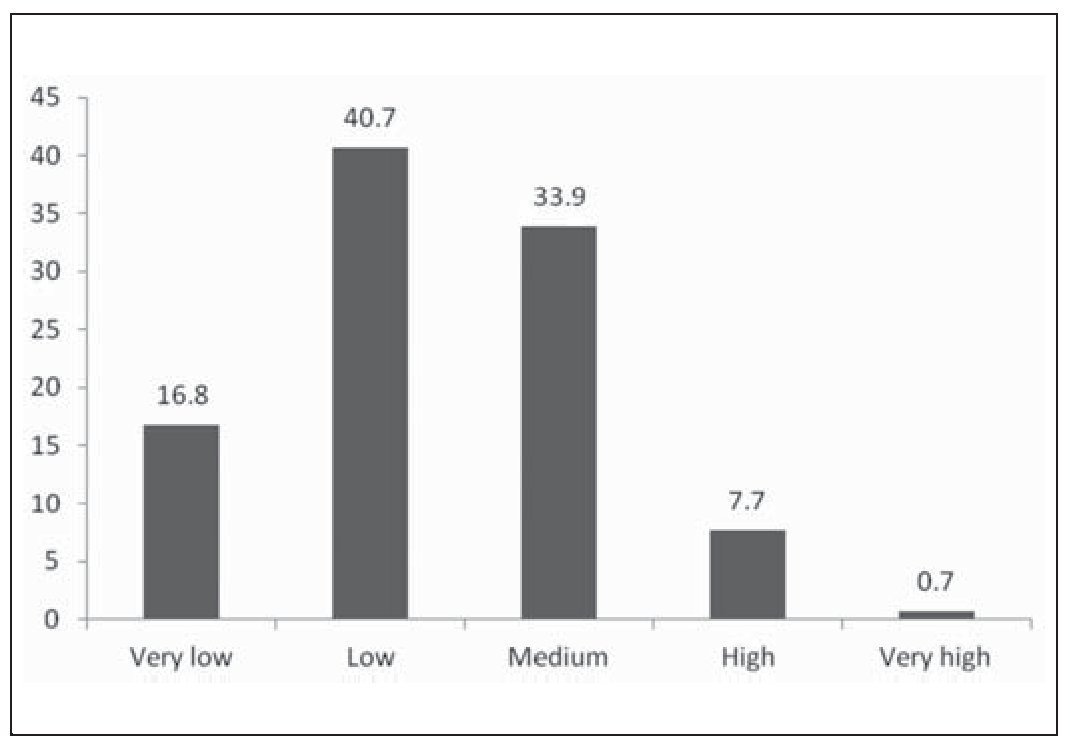

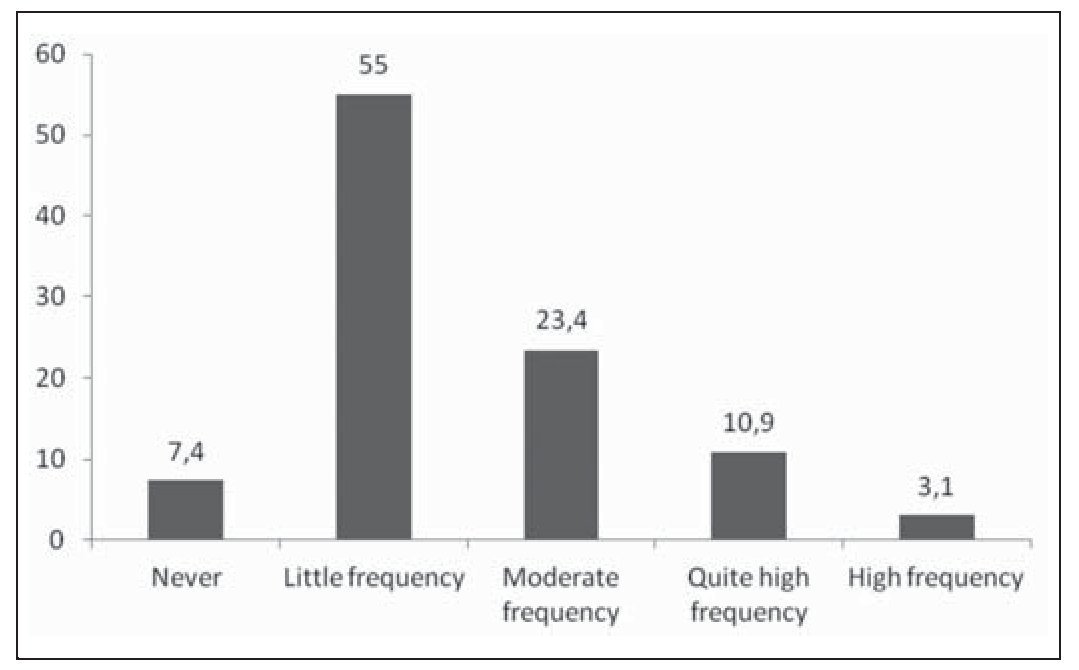

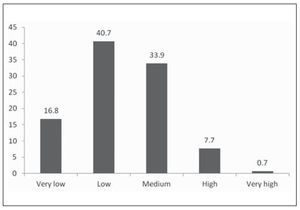

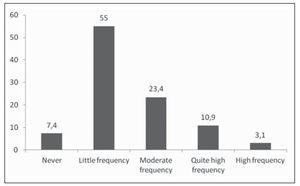

Of all teachers, 40.7% thought that the motivation level of students with regard to acquiring their own knowledge is low, followed by those considering that the students have a medium level (33.9%) (see Figure 9). Furthermore, 55% stated that their students use the tutorial system with very little frequency in order to ask queries about material (see Figure 10).

Figure 9. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to their opinion regarding the level of motivation of students in acquiring their own knowledge.

Figure 10. Percentage of Spanish university Social and Legal Sciences teachers according to the frequency with which students visit tutorial sessions.

Student assessment

The assessment method preferred by Legal and Social Sciences teachers is both objective and competence based (63.6%), 14.5% preferred only objective based assessment, and 10.5% only competence based. In total, 55.6% do not find it difficult to assess the competences actually acquired by students; although part of them do have some difficulty (40.8%). The majority of teachers opted for continuous assessment, that is, throughout the whole academic year, both for theory classes (57%) as for practical classes (87.8%). The teachers that chose the option "other" combine both types of assessment. The rest, carry out assessment once the subject has been completed. 37% declared that there are no differences between the academic results of the old and new systems, although 30% thought they were better before the introduction of the EHEA.

Teacher training

In total, 58.8% thought they have adequate training to teach in the EHEA context. Although 35.8% maintained that they could improve and would need to receive more training. In fact, 74.5% stated that their university provides them with the necessary resources to improve their training (e.g. courses, materials, etc.). The idea of lifelong learning motivates almost all teaching staff, and this is one of the aims of the EHEA (94.3%). Regarding teacher mobility to other European countries, 59.1% aim to carry out a temporary stay abroad, 25.5% stated that they will not and 12.1% had never thought about it.

Coordination, Organization and Resources

Regarding the teacher coordination, 29.6% declared that there is very little and 42.9% stated that there is a lot. A small percentage stated that there is no coordination at all amongst them (8.6%). With regard to organization, the answer of most of those surveyed to one of the challenges of the EHEA, the reduction of the student ratio in the classroom, was that this step was not being carried out in their centre (69.3%). Hence 74.4% stated that they have more than 65 students in the classroom.

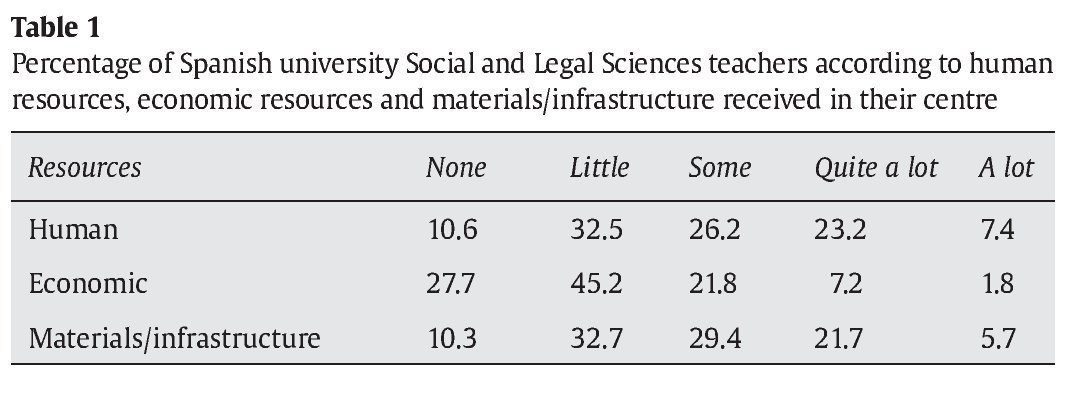

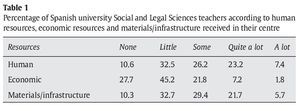

In Table 1 the amount of resources received by teachers in their centre to meet the demands of the EHEA can be seen. In general, the majority of teaching staff receive very little human resources (32.5%), economic resources (45.2%) and materials/infrastructure (32.7%).

Suggestions for Improvement

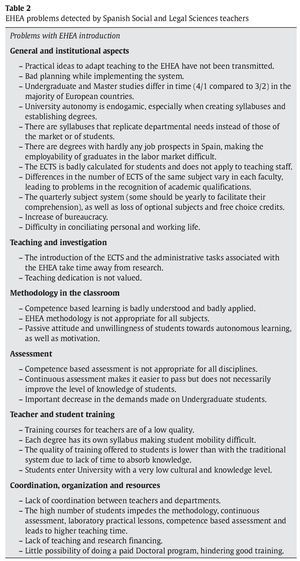

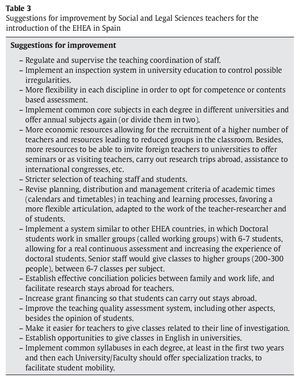

Of all Social and Legal Science teachers, 38.9% wanted to express their opinion regarding the problems surrounding the introduction of the EHEA in Spain (see Table 2). Besides this, they make suggestions in order to improve its consolidation (see Table 3).

Discussion

In this investigation, the aim was to find out the opinion regarding the introduction of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) of a representative sample of Spanish university teachers in the Social and Legal Sciences field, in order to follow the evolution of the changes produced in Higher Education and in what way this process has affected teaching.

In the study of Ariza, Quevedo, Ramiro et al. (2013), the majority of Health Sciences teachers declared that the EHEA adaptation process could be improved. However, teachers in the Social and Legal field are not satisfied with the way in which this process has developed. Furthermore, approximately 76% are not convinced or have doubts that the changes made in Higher Education are going to produce positive effects in university education. Adaptation to the new plans has been easy for more than half of the group, and although it has been a lot of effort for most of the teachers to adapt subject planning to EHEA requirements, almost 80% stated that theirs complies a lot or quite a lot with the guidelines.

A high percentage of teachers showed little or no satisfaction towards the degree structure, maybe (as seen in the open questions) because in Spain the same structure as the majority of EHEA countries should have been implemented, three years for Undergraduate studies and two years for Master studies, so a 3+2 structure rather than 4+1, as in place in Spanish higher education. The European University Association (2010) maintains that one of the problems with European convergence is the length of studies. In a minority of countries the 4+1 structure has been implemented, which could hinder mobility between countries. This makes the organization of mobility complicated both for Spanish students who want to study in another EHEA country, as for the rest of European students who want to study in Spain. Therefore, there is some concern about the recognition of qualifications, especially Master degrees (European University Association, 2010). In this case, most teachers prefer that Master programs cover two academic years, as do the Health Sciences teachers (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al., 2013).

While discussing Postgraduate studies, it is also interesting to look at aspects related to the assessment of research tutoring quality in Doctoral studies and thesis management (Baptista & Huet, 2012). With regard to thesis format, almost 62% prefer the traditional thesis, so it would seem that there are teachers who opt for the new doctoral structure, but with aspects that they think worked well in the past. In the study of Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco et al. (2012), in which the opinion of experts regarding doctoral training was seen, this percentage is reduced, as approximately 40% of Spanish Postgraduate program coordinators, who had received the old quality certification, opted for the classic format. The same results were obtained in the study by Quevedo-Blasco and Buela-Casal (2013). In contrast, most of the teachers in the Health field (47.6%) preferred the compilation of articles (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al., 2013). In the work by Quevedo-Blasco, Ariza, Bermúdez and Buela-Casal (2013) it was found that part of the Social and Legal Sciences teachers prefer the compilation of articles and more than half say that they should be published in journals of the Journal Citation Reports. In this regard, it must be stated that the current interest in studies analyzing indicators of scientific production related to doctoral programs and to the production of researchers (Musi-Lechuga, Olivas-Ávila, & Castro, 2011; Olivas-Ávila & Musi-Lechuga, 2012; Purnell & Quevedo-Blasco, 2013).

Teachers showed a moderate satisfaction towards the grading system, the European Diploma Supplement and teaching accreditation. It can also be seen that they are not satisfied with the development of these changes and are slightly more satisfied with the European Diploma Supplement which, while its use is widespread in the EHEA (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Bermúdez et al., 2013), does not contemplate learning results (Sursock & Smidt, 2011).

A high percentage of teachers would not return to the old system and think that quality in Higher Education will improve very little with the introduction of the Bologna Process. Therefore, there is certain disbelief towards one of the principles of the EHEA as is the improvement in quality. Regarding the information and training offered to teachers about subject adaptation, this could be improved as a high percentage of the teaching staff did not receive what they needed (41.7%) and 23.2% did not know if a plan actually exists, which may have led to uncertainty and some resistance to the change. On the other hand, there are studies that conclude that teacher training has been of a high quality (Vázquez, Alducin, Marín, & Cabero, 2012).

Attitude towards the ERA is generally positive and there is not a unanimous opinion regarding the introduction of the Doctoral Schools, because, although most are indifferent, there are not many differences between those that think they are positive and those that think they are negative. Because of this several studies are being performed on this subject (Castro, Guillén-Riquelme, Quevedo-Blasco, Bermúdez, & Buela-Casal, 2012). Regarding the possibility of completing the thesis in three years, the majority stated that it could be possible depending on the field of investigation. This may be verified in the data of the Directorate General for University Policy (2010), which show that the average length taken by Spanish students to complete the thesis is 6.5 years in Social Sciences, so we would have to wait to see the results of this new measure.

The introduction of the EHEA has brought with it an innovative methodology in the classroom, which was already used before the Bologna Process and that is the professor's role as guide or mediator and a more active role by students in the acquirement of knowledge. However, some of the teachers are still reluctant to act in this way and prefer to teach students mainly through traditional classes. Maybe it is because the introduction of the EHEA has led to more dedication and time to prepare classes. It must be stressed that around 60% stated that, since the introduction of the EHEA, they need more time to organize classes and it takes them much more effort to assess students (39.3%). In the study of Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al. (2013) this percentage is reduced in the Health field, to 47.4% and 26.1% respectively. However, Monereo, Badia, Bilbao, Cerrato and Weise (2009) stated that in certain occasions changing the teaching strategy does not work, as adaptation requires a greater change that would affect professional identity. According to Cardona et al. (2009) the effect that the EHEA could have on teaching quality is not very well valued by teachers because other contextual reforms would have to be made. Nonetheless, the results of this study are quite evenly matched between those professors that think that learning quality will improve with this methodology compared to those that think it will not.

It is also interesting that part of the teaching staff thought that their teacher training could improve. Specifically, Álvarez-Rojo et al. (2011) pointed out that teachers have a greater need for training in skills related to the innovative elements of teaching in the EHEA. Thus, the importance of creating instruments to evaluate teaching activity in Higher Education (Bol-Arreba, Sáiz-Manzanares, & Pérez-Mateos, 2013) and evaluate the effect of general competence acquisition on teaching (Cáceres-Lorenzo & Salas-Pascual, 2012).

More than 94% of the teachers supported lifelong learning. This is positive as they are aware of the need to continue improving their knowledge and skills. In the study by Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al. (2013) 40.6% of teachers in the Health area intended to carry out a temporary stay abroad. This percentage increases in Social and Legal Sciences teachers to approximately 60%. Despite the fact that personal mobility in Europe has grown considerably compared to previous years (European University Association, 2010), part of the teachers do not plan on carrying out any stay abroad (some have not even thought about it), despite the advantages this would have in the improvement of skills. This may be due to the difficulty in obtaining funds.

A larger State inversion in R+D would be essential because this would benefit Spanish research and the university system in general. In 2010, Spain invested 1.37% of its gross domestic product in R+D (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2012), being one of the countries in the European Union (EU) to invest least in this field. Besides, this figure has decreased in recent years. An increase in this type of inversion would make it possible for Spanish Teaching and Research Staff (TRS) to have more opportunities to improve their training by carrying out research in centers abroad. The difficulty in conciliating academic and working life could be another cause impeding mobility (De Filipo, Sanz, & Gómez, 2009).

Another measure in order to make the EHEA principles possible is the reduction of the student ratio in the classroom. However, almost 70% of teachers stated that this is not being done in their centre. This could be related to the resources available by faculties, as teachers receive little human, economic and infrastructure resources, making it practically impossible to reduce the number of students per class. Besides, the more students there are in a class, the more difficult it is that all students participate actively. It is essential that for students to have an active role they are motivated, however, more than half of teachers stated that the level of motivation of their students is low or very low and they do not assist tutorials very frequently. In this regard, Vicario and Smith (2012) maintain that there is also some resistance from students towards the EHEA. Students are a key element in this process, and therefore it is very important to improve processes of self-perception of knowledge by students in order to promote more efficient learning (Sáiz-Manzanares & Payo-Hernanz, 2012). This task is complicated considering the organization and operation of the Spanish education system, in which in the previous stages to university education traditional teaching methods are still used, with a more passive role of students. Added to this is the disinterest shown by students, caused by the poor job prospects in Spain (Tejedor & García-Valcárcel, 2007).

With regard to competence development in students, another of the changes arising from the EHEA, it is proving to be positive as only a small percentage of teachers consider that students acquire little or no competences in their classes. The difficult part is to assess them, as 71% of teachers stated that it requires quite a lot or a lot of effort to assess students, and almost 41% found it quite difficult to assess competences. Besides this, they have doubts that in the Postgraduate level the acquisition of competences necessary to successfully complete it is guaranteed. However, there is a wide debate regarding the usefulness of the competences developed by university students in their professional career. According to Ferrer and Julià (2004), in some cases the competences acquired are not exactly those necessary for their future.

The fact that most of the teachers opt for continuous assessment is very positive. Fraile, López-Pastor, Castejón and Romero (2013) found that in this way students obtain a better academic performance. Although, with regard to the academic results of students, there is not a lot of difference between those that think that the grades of Diploma/Degree students and those of Undergraduate students are practically the same, and those that think they were better before the introduction of the EHEA.

As has been seen there are still doubts regarding this institutionalization process. There was some uncertainty in the group as to if the changes are being carried out correctly, and above all, if they will be beneficial for Spanish university education. In any case, it can be noted that all teachers coincide in that a higher State investment is essential for the consolidation of the EHEA, and that financing and quality are related (Buela-Casal et al., 2013).

In conclusion, it cannot be stated that teachers are satisfied with this adaptation, because it is still not clear if the positive effects produced in Higher Education compensate for the effort that is being carried out. While it is true that we would have to wait to see if the EHEA will start to function correctly, as a reform in education does not produce changes on a short-term basis, nor does it improve the quality of education automatically (Sola, 2004).

Finally, the continued legislative changes and controversial measures unrelated to European convergence applied to Spanish university teaching staff, may have affected opinion regarding the EHEA. Therefore, almost half of the group spoke out in the open question to give a negative vision of the process, due to difficult work conditions experienced by teaching and research staff in Spanish universities. Likewise, the fact that teachers from some institutions have participated more than others in the study could influence the results, as the EHEA has been implemented differently in each of the Spanish universities. It must also be considered that satisfaction was evaluated in a specific field of knowledge. It has been seen that, in certain aspects, there are differences to the opinion of Health Sciences teachers (Ariza, Quevedo-Blasco, Ramiro et al., 2013).

Conflict of interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project has been financed by the Directorate General of University Policy (EA2011-0048). The authors would like to thank Dr. Diego Sevilla Merino and Dr. Wenceslao Peñate Castro for their collaboration in the review of the survey.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Manuscript received: 23/07/2013

Revision received: 29/09/2013

Accepted: 02/10/2013

http://dx.doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2014a2

*Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to

Tania Ariza, Brain and Behaviour Research Center (CIMCYC),

Campus de Cartuja s/n. 18011 Granada (Spain).

E-mail: tariza@ugr.es

References

Aghion, P., Dewatripont, M., Hoxby, C., Mas-Colell, A., & Sapir, A. (2008). Higher aspirations: An agenda for reforming European universities. Retrieved from http://www. bruegel.org/publications/publication-detail/publication/1-higheraspirations-an-agenda-for-reforming-european-universities/

Álvarez-Rojo, V., Romero, S., Gil-Flores, J., Rodríguez-Santero, J., Clares, J., Asensio, I. ... Salmeron-Vilchez, P. (2011). Teachers' needs for teaching in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Relieve, 17(1). Article 1. Retrieved from http://www.uv.es/ RELIEVE/v17n1/RELIEVEv17n1_1eng.htm

Anaya, D., & Suárez, J. M. (2007). Satisfacción laboral de los profesores de Educación Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria. Un estudio de ámbito nacional [Job satisfaction of infant, primary and secondary education teachers. A national study]. Revista deEducación, 344, 217-243.

Ariza, T., Bermúdez, M. P., Quevedo-Blasco, R., & Buela-Casal, G. (2012). Evolución de la legislación de doctorado en los países del EEES [Evolution of doctoral legislation in the EHEA countries]. Revista Iberoamericanade Psicología y Salud, 3, 89-108.

Ariza, T., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Bermúdez, M. P., & Buela-Casal, G. (2012). Los estudios de doctorado en España: De la Mención de Calidad a la Mención hacia la Excelencia [Doctoral studies in Spain: From the quality certification to the excellence certification]. Aula Abierta, 40, 39-52.

Ariza, T., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Bermúdez, M. P., & Buela-Casal, G. (2013). Analysis of postgraduate programs in the EHEA and the USA. Revista dePsicodidáctica, 18, 197-219. doi: 10.1387/RevPsicodidact.5511

Ariza, T., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Ramiro, M. T., & Bermúdez, M. P. (2013). Satisfaction of Health Science teachers with the convergence process of the European Higher Education Area. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 3, 197-206.

Baptista, A.V., & Huet, I. (2012). Supervisors and students' conceptions of the nature and value of the doctorate. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 3, 211-228.

Bengoetxea, E., & Buela-Casal, G. (2013). The new multidimensional and user-driven higher education ranking concept of the European Union. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 13, 67-73

Bol-Arreba, A., Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., & Pérez-Mateos, M. (2013). Validación de una encuesta sobre la actividad docente en Educación Superior [Validation of a survey regarding teaching activity in Higher Education]. Aula Abierta, 41, 45-54.

Buela-Casal, G., Bermúdez, M. P., Sierra, J. C., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Guillén-Riquelme, A., & Castro, A. (2013). Productividad y eficiencia en investigación por comunidades autónomas españolas según la financiación (2011) [Research productivity and efficiency in Spanish autonomous communities according to financing]. Aula Abierta, 41, 87-98.

Cáceres-Lorenzo, M. T., & Salas-Pascual, M. (2012). Valoración del profesorado sobre las competencias genéricas: su efecto en la docencia [Evaluation of teaching staff regarding general competences: Their effect on teaching]. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 3, 195-210.

Cardona, A., Barrenetxea, M., Mijangos, J. J., & Olaskoaga, J. (2009). Concepto y determinantes de la calidad de la Educación Superior. Un sondeo de opinión entre profesores de universidades españolas [Concept and decisive aspects of quality in Higher Education. An opinion Survey amongst Spanish university teachers]. Archivos Analíticos de PolíticasEducativas, 17, 1-25.

Castro, A., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Bermúdez, M. P., & Buela-Casal, G. (2012). Doctoral Schools in Spain: Suggestions of Professors for their Introduction. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 17,199-217. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1387/RevPsicodidact.1558

De Filipo, D., Sanz, E., & Gómez, I. (2009). Movilidad científica y género. Estudio del profesorado de una universidad española [Scientific mobility and gender. Study of the teachers of a Spanish university]. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 71, 351-386.

De Miguel, M. (2006). Metodologías de enseñanza y aprendizaje para el desarrollo decompetencias. Orientaciones para el profesorado universitario ante el EspacioEuropeo de Educación Superior [Teaching and learning methodologies for the development of competences. Advice for university teachers in view of the European Higher Education Area]. Madrid, Spain: Alianza Editorial.

Dirección General de Política Universitaria. (2010, October). Avances en el EEES y el EEI. Elnuevo doctorado. [Advances in the EHEA and the ERA. The new doctoral studies]. Jornadas sobre la Nueva Configuración del Doctorado en Europa, Universidad del País Vasco, San Sebastián, Spain. Retrieved from http://www.ikasketak.ehu.es/ p266-shprdoct/es/contenidos/informacion/doctorado_jornadas/es_jornadas/adjuntos/MORENO_NuevoDoctorado_EHU.pdf

European Commission. (2008a). Progress in Higher Education reform across Europe.Funding reform. Volume 1. Executive summary and main report. Retrieved from http:// ec.europa.eu/education/higher-education/doc/funding/vol1_en.pdf

European Commission. (2008b). Progress in Higher Education reform across Europe.Governance and funding Reform. Volume 2. Methodology, performance data,literature survey, national system analyses and case studies. Retrieved from http://ec.europa. eu/education/higher-education/doc/governance/vol2_en.pdf

European University Association. (2010). Trends 2010: A decade of change inEuropean higher education. Retrieved from http://www.eua.be/eua-workandpolicy-area/ building-the-european-higher-education-area/trends-ineuropeanhigher-education/trends-vi.aspx

Fernández, M. J., Carballo, R., & Galán, A. (2010). Faculty attitudes and training needs to respond the new European Higher Education challenges. Higher Education, 60, 101-118. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9282-1

Ferrer i Julià, F. (Dir.) (2004). Las opiniones y actitudes del profesorado universitariodelante el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: Propuestas para laimplementación del sistema de créditos europeos (ECTS) [The opinions and attitudes of university staff regarding the European Higher Education Area: Proposals for the implementation of a European Credit System (ECTS)]. Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia. Retrieved from http://www.psico.uniovi.es/Fac_Psicologia/paginas_EEEs/Adaptacion_de_profesorado/Preparacion_del_Profesor/opiniones_informeECTS_oct04.pdf

Fraile, A., López-Pastor, V., Castejón, J., & Romero, R. (2013). La evaluación formativa en docencia universitaria y el rendimiento académico del alumnado[The education evaluation in university teaching and the academic performance of students]. Aula Abierta, 41, 23-34.

Hartley, J. (2012). New ways of making academic articles easier to read. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12, 143-160.

Lisbon European Council. (2000). Presidency Conclusions. Retrieved from http://www. europarl.europa.eu/summits/lis1_es.htm.

Monereo, C. (2010a). La formación del profesorado: una pauta para el análisis e inter-vención a través de incidentes críticos [Teacher training: A guideline for the analysis and intervention of critical incidents].Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 52, 149-178.

Monereo, C. (2010b). ¡Saquen el libro de texto! Resistencia, obstáculos y alternativas en la formación de los docentes para el cambio educativo [Get the textbooks out! Resistance, obstacles and alternatives in teacher training for educational change]. Revista de Educación, 352, 583-597.

Monereo, C., Badia, A., Bilbao, G., Cerrato, M., & Weise, C. (2009). Ser un docente estratégico: Cuando cambiar la estrategia no basta [Strategic teaching: When changing strategy is not enough]. Cultura y Educación, 21, 237-256.

Musi-Lechuga, B., Olivas-Ávila, J. A., & Castro, A. (2011). Productividad de los programas de doctorado en Psicología con Mención de Calidad en artículos de revistas incluidas en el Journal Citation Reports [Productivity of psychology doctoral programs with quality certification in articles of journals included in the Journal Citation Reports]. Psicothema, 23, 343-348.

Olivas-Ávila, J. A., & Musi-Lechuga, B. (2012). Doctorados con mención de excelencia en psicología: Evidencia en tesis doctorales y artículos en la Web of Science [Psychology doctoral programs with excellence certification: Evidence in doctoral theses and articles in the Web of Science]. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12, 503-516.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2012). Gross domesticexpenditure on R&D. Retrieved from http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-andtechnology/gross-domestic-expenditure-on-r-d_2075843x-table1

Purnell, P. J., & Quevedo-Blasco, R. (2013). Benefits to the Spanish research community of regional content expansion in Web of Science. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 13, 147-154.

Quevedo-Blasco, R., Ariza, T., Bermúdez, M. P., & Buela-Casal, G. (2013). Actitudes del profesorado universitario español: Formato de tesis doctorales, docencia e investigación [Attitudes of spanish university teaching staff: Format of doctoral theses, teaching and investigation]. Aula Abierta, 41, 5-12.

Quevedo-Blasco, R., & Buela-Casal, G. (2013). Evaluación de tesis doctorales: propuestas de mejora [Evaluation of doctoral theses: Improvement suggestions]. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 30, 69-78.

Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., & Payo-Hernanz, R. J. (2012). Auto-percepción del conocimiento en Educación Superior [Knowledge self-perception in Higher Education]. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 3, 159-174.

Sola, M. (2004). La formación del profesorado en el contexto del Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior. Avances alternativos [Training of teaching staff in the context of the European Higher Education Area. Alternative advances]. Revista Interuniversitaria deFormación del Profesorado, 18, 91-105.

Sursock, A., & Smidt, H. (2011). Resumen ejecutivo del Informe Trends 2010 [Executive summary of the 2010 Trends Report]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 2, 165-172.

Tejedor, F. J., & García-Valcárcel, A. (2007). Causas del bajo rendimiento del estudiante universitario (en opinión de los profesores y alumnos). Propuestas de mejora en el marco del EEES [Causes of the low performance of university students (according to teachers and students), Improvement suggestions in the EHEA context]. Revista de Educación, 342, 443-473.

Vázquez, A. I., Alducin, J. M., Marín, V., & Cabero, J. (2012). Formación del profesorado para el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior [Teacher training for the European Higher Education Area]. Aula Abierta, 40, 25-38.

Vicario, A., & Smith, I. (2012). Cambio de la percepción de los estudiantes sobre su aprendizaje en un entorno de enseñanza basada en la resolución de problemas [Change of perception of students regarding learning in a teaching environment based on the resolution of problems]. Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 11, 59-75.