Within the framework of asymmetric information, the present work has the aim of analysing the influence of relationship banking in bankruptcy resolution, with particular reference to firm size. The obtained results, from a sample of 622 micro- and small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) non-financial and unlisted firms that filed for bankruptcy in 2010 (resolved by the end of 2014), allow us to conclude that: (1) SMEs are more likely to survive than micro firms; (2) the number of relationships banking is not relevant; (3) maintaining relations with one of the big banks, especially the largest bank in a country, increases the likelihood of reorganization, as opposed to liquidation.

At the international level, banks have traditionally been one of the most important financial sources for firms. In addition, the role of banks, and hence banking relationships, is of great relevance in countries such as Spain, with a bank-centred financial system and financial markets with limited development. In this sense, when compared to other creditors, banks present a comparative advantage because they are better-informed due to their continuous relations with firms (Diamond, 1984; Fama, 1985). Elsas (2005) defines relationships banking as an implicit long-term contract between a bank and its borrower. Because of the repeated interactions between the financial entity and its client, the former accumulates private information about the latter, which establishes a narrow relation between both of them. In this sense, the literature about relationships banking is based on the existence of information asymmetries between the banking entity and its clients, asymmetries that are more relevant in small firms. According to Shimizu (2012:857), “lending relationship attracts much concern of some economists and policymakers because small firms have many difficulties in obtaining funds from public capital markets”.

That informative advantage achieves great relevance in the case of bankrupt firms because, in that situation, the problems related to the limited quality of information are greater. Thus, Rauterkus (2009) asserts that “bank lending leads to a lower cost of financial distress and increases the chances of successful debt restructurings.” Additionally, in a bank-centred financial system, it is almost impossible that a firm can be reorganized without bank support (Dewaelheyns and Van Hulle, 2009). Along the same line, Park (2000) argues that the bank's value added, as principal lender, is its experience in collecting information about the borrowers. He asserts that banks usually favour reorganization in the bankruptcy process.

However, very few works have analysed the impact of banking relationships when firms are in financial distress. According to Li and Srinivasan (2010:3): “This is an important gap in the literature as the benefits of bank lending arise because of the (assumed) better screening ability or better refinancing decisions of banks relative to capital markets during borrower distress”. Along those same lines of reasoning, Sundgren (1998) considers that studies of small and mid-sized firms are important because, although the majority of the insolvent firms are small, more empirical studies on bankruptcy are focused on large, publicly owned firms.

In addition, the literature on bankruptcy resolution identifies two opposite types of systems that act as a function of the applied legislation: debtor-friendly and creditor-oriented.1 These systems are different in several aspects, such as the protection of rights of control in the event of an automatic suspension of assets (rule of automatic suspension), if managers can remain in operation during the reorganization or liquidation (rule debtor in possession), and if there are priorities for new funding (absolute priority rule). In creditor-oriented systems, creditors receive much more protection from the law, and they are granted an advantageous role in the negotiation process. However, in debtor-friendly systems, protection is limited. These differences in creditors’ rights protection can be the cause of disagreement in the creditor's position during bankruptcy resolution proceedings. In this sense, Davydenko and Franks (2008) found that the national bankruptcy codes have been important determinants of outcomes of distress. As Wang (2012) argues, this occurs despite significant adjustments in banks’ practices in response to particular provisions of their respective codes.

Related to the bankruptcy legislation in Spain, the current law was promulgated in 2003 (Ley Concursal, 2003), although afterwards several modifications have been made with the aim of improving its efficiency. Concretely, the Spanish legislation takes into account the priority of the preferred creditors to aid recover before other parties, and the opportunity of abstention in the approval of the agreement, which make possible that such creditors can preserve their rights. On the other hand, the Law establishes the suspension of processes of execution that had been initiated before the bankruptcy proceeding filing and, on the other hand, prohibits starting any other procedure until a year has passed from the date of the bankruptcy proceeding filing or the liquidation (a violation of the priority rule).

Regarding the bankruptcy resolution, the Law 22/2003 offers two alternatives to financially distressed firms: liquidation bankruptcy or reorganization, which requires the agreement of all of the creditors. According to the preamble of the Spanish bankruptcy proceeding Law, reorganization is the normal solution from the proceedings, causing the Law to promote a series of measures whose purpose is to reach a satisfactory agreement with the creditors. The reorganization proposal must be approved at the creditors’ meeting. This meeting is made up of creditors whose credits make up at least half of the ordinary credit value. A classification of creditors can be established according to the credit priority established in the Law.2 The Law is flexible with respect to the content of the proposed agreement. Thus, the proposal could consist of propositions of reduction and moratorium of debt or the accumulation of both; however, debt reductions cannot exceed half of the sum of each ordinary credit, and debt moratoriums cannot continue for more than five years after the approval of the agreement. Moreover, alternative propositions are admitted, such as a conversion of debtors credit into equity instruments or similar stakes.

Another possibility of the bankruptcy proceeding resolution is liquidation. Liquidation can occur at the request of the debtor at the moment of the bankruptcy proceeding filing or during the reorganization process if it is impossible to meet promised payments. Likewise, liquidation can be requested by the creditors. It is noteworthy that firm management and possession of patrimony are suspended during the liquidation process. Moreover, the court resolution that initiates the liquidation process entails the dissolution of the firm and the substitution of the managers by bankruptcy administrators. The objective of the liquidation procedure is to collect the assets of the firm, determine the outstanding debt, and pay the debt off in the way and order stated in the Law. The liquidation process can lead to a piecemeal or complete liquidation, in which case the creditors can retain the synergies generated by the firm.

In this context, the aim of this work is to analyse the incidence of relationships banking in bankruptcy resolution, with special reference to firm size. Based on the theoretical arguments about asymmetric information, it is predicted, on the one hand, that larger firms and/or those that maintain relationships with fewer banks, will be more likely to reach an agreement with creditors. On the other hand, it is expected that when firms maintain relationships with a great and reputed bank, the likelihood of reorganization is greater.

The study has been made using a simple of 622 Spanish SME firms that have entered the bankruptcy process in 2010 and whose bankruptcies have been resolved by December 2014. Spain presents an opportunity of study for several reasons. First, Spain is a country with a great banking orientation, to the detriment of financial markets. Secondly, the country has a predominance of SME firms. Thirdly, the Spanish legislation about bankruptcy is situated in an intermediate position regarding creditors’ rights protection, following the index of Djankov et al. (2007), and in Spain the use of the legal bankruptcy process is less common than in other similar countries (García-Posada and Mora-Sanguinetti, 2012). The obtained results show that larger firms and those that maintain relationships with larger financial entities are more likely to be reorganized. The number of banking relationships does not have significant incidence in bankruptcy resolution.

The remainder of the study is structured as follows. Section 2 analyses theoretical arguments and presents the hypotheses. Section 3 describes methodological aspects, while Section 4 presents the results of the empirical study. The fifth and final section is dedicated to our concluding remarks.

2Theoretical background and hypothesis2.1Firm size and bankruptcy resolutionSize is considered in the literature as a proxy of asymmetric information. Thus, it is possible that the smallest firms, with greater information asymmetries, have a lower probability of reaching an agreement than the largest firms in the bankruptcy process. The reason is that creditors will be more willing to trust information from larger firms regarding the firm's viability, and the creditors probability of recovering the debt depends on that information (Ayotte and Morrison, 2009; Jacobs et al., 2012).

Furthermore, White (1994) theoretical model of bankruptcy emergence predicts differences in emergence between small and large firms. This author argues that a larger firm size increases the survival probability because assets are more specific, and this situation reduces the number of purchasers that are interested in such firms. In this line, Aghion et al. (1992) assert that reorganization would be, ceteris paribus, a better option for larger firms in financial distress because, if the firm is sold, few bidders may have the possibility of raising the financing.

For their part, Denis and Rodgers (2007) find that larger firms are more likely to survive bankruptcy and emerge as independent firms, which “may be because large firms are deemed too big to fail or because they are more likely to have sufficient resources to survive […] or because the larger firms are more likely to be economically viable.” (p. 112). In addition, the largest firms are generally supported by governments for strategic reasons. For example, the Korean government tends to protect large firms from liquidation because the liquidation of larger firms would cause social problems (Kim et al., 2008).

Finally, most empirical studies consider size to be a relevant factor in bankruptcy resolution (e.g., White, 1994; Campbell, 1996; Sundgren, 1998; Ravid and Sundgren, 1998; Thorburn, 2000; Bryan et al., 2002; Barniv et al., 2002; Denis and Rodgers, 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Rauterkus, 2009; Wang, 2012). Those studies find that the largest firms are more likely to be reorganized. These arguments allow us to state the first hypothesis in the following terms:H1 The largest firms are more likely to reach an agreement with their creditors.

The literature of financial intermediation (Diamond, 1984) shows that financial intermediaries need to produce the information necessary to monitor borrowers, which is a comparative advantage with respect to others creditors. This information production requires a close association between the bank and its borrower, which is referred to in the literature as relationship banking (Marini, 2013). Following Boot (2000), the relationships banking supposes the provision of financial services by a banking institution, which invests in obtaining relevant information from its clients and evaluates the profitability of those investments through multiple interactions with the same client in the long term. On his behalf, Elsas (2005) defines banking relationships as an implicit long-term contract between the bank and its borrower. Because of repeated interactions between the bank and its customer, the former accumulates private information about the latter, which establishes a narrow relationship between the two.

The credit relationship implies two actors, debtors and creditors, and is ruled by information asymmetries, which are a type of Principal-Agent model insofar as one party is better informed than the other. This problem is particularly important for small firms (Frouté, 2007). In this sense, the literature about relationship banking is related to asymmetric information especially between banks and their borrowers, and, concretely, those clients from which it is more difficult to obtain information, such as families or SMEs. Specifically, relationships banking can reduce information asymmetries due to the continuous contact with those customers. In this line, Marini (2013:273) asserts: “The relationship banking adds value because its helps controlling conflicts of interest between lenders and borrowers and eliminate the duplication of monitoring costs through delegated monitoring, and it provide flexibility in debt contracts”.

Firms can maintain unique or multiple relationships banking. Among the most remarkable benefits of a unique relationship banking, is the possibility for greater contractual flexibility than in financial markets (Rajan, 1992; Diamond, 1991; Bolton and Freixas, 2000), the rise in control exerted by the credit institution (Rajan, 1992), the development of a reputation (Diamond, 1991), the maintenance of some confidentiality about firm information (Yosha, 1995) and a greater inclination to transmit private information (Bhattacharya and Chiesa, 1995). Regarding disadvantages, this type of banking relationship causes an asymmetric information evolution between the bank lender and other competitor entities, which gives to the former certain monopolistic powers in financial negotiations (Sharpe, 1990; Rajan, 1992; Boot, 2000). In this line, the private information that the bank obtains in its relationships with the firm can produce an informative monopoly (hold up) that can be used to the detriment of the borrower.

On the other hand, firms can choose several relationships banking, which can reduce the informative monopoly exerted by only one financial entity, but, at the same time, decreases the incentives of each entity to invest in the relationship. Ongena and Smith (2000) suggest an explanation that multiple relationships can reduce the value of acquiring information by each bank when they are individually considered. Among the arguments that are postulated in favour of the maintenance of multiple relationships, stand outs include an increase in competition and risk diversification, in the firm and in the bank entity (Boot and Thakor, 2000; Degryse and Ongena, 2005).

Information asymmetry in relationships banking can be more evident when a firm is in financial distress because of uncertainty about the firm's viability (Rosenfeld, 2014). In this sense, by reducing informative asymmetries (Diamond, 1984), relationships banking can prevent early liquidation and stimulate recovery as result of continuous monitoring and a fast intervention after the signals of decline appear (Balcaen et al., 2011). Von Thadden (1995) also argues that monitoring enables banks to make efficient liquidation decisions because they learn about firm quality in addition to short-term outcomes of investments.

To the extent that the relationship is developed by the bank, it knows better the cash flows of the client and the frequency of its banking operations, and can obtain “soft” information about the firm's ability to repay debt. As Rosenfeld (2014) asserts, this information can be related to “information on management's ability to overcome adverse situations, the firm's internal control of spending, and the veracity of the firm's financial statements” (p. 403). Access to this type of information can make it easier for the bank to reach an agreement with the firm in a bankruptcy process.

In addition, reorganization in a bankruptcy process requires a negotiation process, and the firm is more likely to obtain an agreement if debt is more concentrated because coordination among creditors is easier (Von Thadden et al., 2010; Tsuruta and Xu, 2007). However, although Franks and Sussman (2005) agree with this argument, they also assert that concentrated debt “may provide the bank with an incentive to be lazy and avoid the effort and the risk involved in restructuring the firm” (p. 69).

The aspects traditionally analysed in relationships banking are the number of bank entities that work with the firm (and especially those that provide fund to the firm), the length of the relationship or the number of banking services used by the firm. In this sense, Rosenfeld (2014) asserts that the number of entities is an indicator of the complexity of the lending because: “the more entities there are within an organization, the more likely it is to have impediments with conveying “soft” information” (p. 414). This author finds a positive effect on firm emergence from distress when the firm has five or fewer entities.

According to these arguments, the second hypothesis is stated:H2 Firms with a lower number of relationships banking are more likely to reach an agreement with its creditors.

Undoubtedly, one of the most important aspects in a good banking relationship is the trust between the firm and the bank. To a large extent, this trust is based on the bank's reputation, which is closely related to the size of the bank. The importance of bank reputation has been exposed in several studies about banks entities (Duca and Vanhoose, 1990; Boot et al., 1993; Aoki and Dinç, 1997; Dinc, 2000). Related to bankruptcy firms, Chemmanur and Fulghieri (1994) argue that banks that care for reputation devote more resources towards evaluating projects and are able to make efficient liquidation decisions when a firm is in financial distress. Moreover, banks make inefficient liquidation decisions with lower probabilities because they receive more precise signals, i.e., the probabilities of receiving good signals conditioned on true good states are higher (Simishu, 2012). In this line, Moussu and Troege (2013) consider that, if a bank wants to maintain a good reputation, it must have a low ratio of client firms that have filed for bankruptcy. Those authors, in a study related to bank reputation and lending policies, assert that “Too many failures among a bank's existing clients will destroy its reputation because potential borrowers will suspect it not to provide an appropriate level of support. As a consequence, a bank might need to reduce the failure rate of its credit portfolio by refusing loans to profitable but risky companies” (p. 1).

Therefore, in a bankruptcy context and to not destroy its reputation, a bank with a good reputation will not be interested in a great amount of liquidations. The reason is that, perhaps, other potential clients would think that the bank liquidates collateral because it is only worried about itself. This idea would be detrimental for the future business of the bank because the bank's attitude towards bankruptcy is relevant for the decisions of future clients. In this sense, Aoki and Dinç (1997:11), speaking about the main bank in Japan, assert that “By investing in reputation, the main banks were able to derive (relational) rents from the same and/or other firms in the future”.

On the other hand, a well-reputed bank will prefer to reach as many agreements as possible as a way to demonstrate that it can provide an adequate level of support to the firm in bankruptcy, and, in general, to its current and future clients. However, this attitude to preserve its reputation may be undermined by information asymmetries. If other borrowers cannot distinguish between the real situation of the distressed firm, the bank's concern about its reputation could lead it to rescue firms that are not economically viable (Aoki and Dinç, 1997).

The previous arguments about the role of the bank reputation in the bankruptcy process make it possible to formulate the following hypothesis:H3 If the firms have relationships with a reputed (larger) bank, the likelihood of reaching an agreement is greater.

In addition, the bank's size and, consequently, its reputation are related to its capability to obtain information from its debtors, which also depends on the size of the client firms. In this sense, Berger et al. (2005) argue that small banks might be at a comparative advantage in making loans based on soft information and, hence, larger banks are more apt to lend to larger firms that have better accounting records. In the same line, Simishu (2012) investigates whether small banks play the role of reducing the bankruptcy rate or enhancing the recovery probability of distressed small businesses. This author asserts that large hierarchical banks are at a comparative disadvantage when information about an investment project is soft because the decentralized organizational structure of small banks allows their loan managers to have a higher research effort incentive. Furthermore, Shimizu (2012:858) asserts: “small banks might play the role of preventing small firms in distress from bankruptcies or postponing their bankruptcies by financial support”. This author provides empirical evidence that small banks, rather than relatively large banks, specialize more in relationship loans to unlisted firms in the local credit market of Japan. In particular, this sheds some light on how small banks enhance Japanese small firms’ recovery rate from financial distress. The results indicate that the emergence of bankruptcy in unlisted firms is lower when the loans ratio of small banks is less than that of relatively large banks.

Taking into account the previous ideas, the following hypothesis is formulated:H4 The smallest firms, which have relationships with a reputed bank (larger), are less likely to reach an agreement with their creditors.

The sample selection starts with the list of bankruptcy proceedings published in the Official Gazette (B.O.E.) obtained through the WebConcursal by non-financial companies with the legal form of public and private limited liability companies in 2010, amounting to 4736 companies. Information concerning banking relationships as well as financial statements of the companies have been obtained from the database SABI.3 Nevertheless, SABI database is updated regularly and the historical series are not available for some variables, such as the banks. For this reason, it has been necessary to resort to previous updates of the database available in DVD. Taking this into consideration, as well as the annual accounts in SABI for 2008 for legal bankruptcies presented in the first half of 2010, and the year 2009 for legal bankruptcies presented in the second half of 2010, the number of companies with the required information is 832.

Additionally, with the aim of knowing the phase of the bankruptcy process in which each lies, it is necessary to check each of the bankruptcies in the database of the Public Register of Insolvency Resolutions of the Spanish Ministry of Justice (Registro Público de Resoluciones Concursales). At the end of 2014, only 667 had been resolved, that is, had passed from the common phase to the next phase. This database provides information concerning the evolution of the process, which allows one to know whether there has been an agreement or arrangement with creditors (reorganization) or if the liquidation phase has started. This daunting task of analysing each bankruptcy is what justifies the study of a single year.

On the other hand, studies about banking relationships usually refer to small and medium firms because they present major problems of asymmetric information. For this reason, companies with sales and total assets exceeding 50 million euros have been eliminated. The final sample consists of 622 SMEs, of which 250 (40%) are micro enterprises (total asset less than 2 million euros), and 372 (60%) are small- and medium-sized (assets over 2 million). This is one of the criteria set out for the definition of SMEs in the Recommendation of the European Commission of May 6, 2003.4

3.2VariablesThe key variables referred to are bankruptcy resolution, company size and banking relationships, namely, the number of banks and the bank size. A number of control variables, obtained from previous empirical evidence, have been considered, such as profitability, bank debt, collateral, liquidity, age and industry.

Dependent variable. The dependent variable is the bankruptcy resolution, which takes the value 1 if the company is reorganized and zero if it is liquidated. The criteria considered in this study to distinguish between companies that have solved the process is to have passed the common phase, i.e. that has occurred the beginning of the phase of agreement or liquidation.5 Sometimes, the companies enter the liquidation after reaching an agreement with its creditors, either for breaching the agreement or for other reasons. These firms are eliminated for the robustness analysis.

Explanatories variables

Firm Size (FSize). The size has been approximated by a dummy variable (FSizeD) that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium and 0 if it is a micro business. To distinguish between those groups, the total asset limit of 2 million euros, as established by the EC Recommendation, has been used. The logarithm of total assets (FSizeL), a continuous variable, is considering as robustness analysis. Assets have been used as a proxy for size in numerous studies about the resolution of financial distress (e.g., Sundgren, 1998; Bryan et al., 2002; Barniv et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2008; Ayotte and Morrison, 2009; Jacobs et al., 2012).

Number of entities (NBank). The number of banking relationships has been used in several studies to represent the degree of concentration of relationships (e.g., Montoriol, 2006; Ogawa et al., 2007; Bonfim et al., 2008). Among the studies that consider the number of banking relationships as an explanatory variable in resolution failure is Rosenfeld (2014).

Bank size. Following Rosenfeld (2014), bank size is approximated by the volume of assets.6 Two dummy variables are created. The first (BigBank) takes the value 1 if the firm maintains relationships with the largest bank, and the second takes the value 1 if the firm operates with one of the five largest bank entities (Big5Bank).7

Control variables. According to previous works, which analyse bankruptcy resolution, variables regarding profitability, bank debt, bank debt coverage, liquidity, age and firm activity have been considered:

Profitability (ROA). White (1994) suggests that firms that have higher expectations regarding their future earnings have a higher probability of survival. The studies about bankruptcy resolution consider the profitability of the firm in the previous period as a proxy of future earnings (e.g., Casey et al., 1986). Along these lines, Bergström et al. (2002) also assert that the previous results affect the probability of reorganization; thus, the firms with the poorest results are less likely to achieve a successful reorganization. Particularly, in the present work, ROA is used, computed as earnings before interest and taxes to total asset (e.g., White, 1994; Bryan et al., 2002, 2010; Leyman et al., 2011).

Bank debt. The bank debt ratio measures the relative importance of bank debt in the overall debt, which is considered a proxy of the power of banks in the negotiation process (Wang, 2012). The variable is calculated using the ratio between bank debt, short-term and long-term, and total debt. Other studies that also consider this ratio are Fisher and Martel (1995), Thorburn (2000), Rauterkus (2009) and Jacobs et al. (2012). Some authors (e.g., Rauterkus, 2009) argue that a greater volume of bank debt represents a higher probability of liquidation, because, in financial systems where these entities do not face the competition from other sources of funding (as the case of Spain is), banks are not involved in solving financial problems.

Coverage of bank debt (CobBankDebt). One of the main reasons that creditors consider in order to decide the liquidation or the continuation of the company is the existence of assets that can be used for debt recovery, if it is necessary. Thus, some authors consider different variables that relate assets with debt, either total assets or tangible assets, total debt or financial debt (e.g., Bergström et al., 2002; Dewaelheyns and Van Hulle, 2009). In this paper, the ratio of non-current assets and bank debt, as proxy for the degree of coverage of bank debt, is used. Specifically, a dummy variable is created which takes the value 1 if this ratio is greater than one and zero otherwise. It is expected that a higher coverage is associated with a greater likelihood of reorganization, although some authors (e.g., Bergström et al., 2002) argue that secured creditors (particularly banks) prefer to opt for liquidation when their debt is secured.

Liquidity. Liquidity problems are one of the primary reasons that causes bankruptcy filings. In fact, the Spanish Law notes that current or imminent liquidity problems, defined as the impossibility of fulfilling payments, are the objective requirement to declare the bankruptcy. There are different forms of estimating liquidity. In the present study, liquidity is measured by the ratio of current assets and current liabilities (e.g., Kim et al., 2008; Leyman et al., 2011).

Age. The age is approximated by the logarithm of the number of years between the constitution of the firm and the date of the bankruptcy. This variable has been considered in different studies about bankruptcy resolution (e.g., Bergström et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2008; Rosenfeld, 2014) and it is explained in the sense that greater accumulated experience is a sign of a good reputation and a guarantee for financial entities and creditors in general. Thus, a positive relationship between the age and the likelihood of reorganization is expected.

Sector. This variable attempts to summarize certain aspects that are more related to the sector activity rather than to the firm. Among the studies of bankruptcy resolution that consider sectors are those of Campbell (1996), Fisher and Martel (2012), Sundgren (1998), Bergström et al. (2002) and Balcaen et al. (2011). In this study, six dummies variables are considered: Industry, Construction, Commerce, Transport and Communications, Business Services, and Hotels and Other Services.

3.3Estimation methodConsidering that the dependent variable is dichotomous, a probit model, which tries to determine the likelihood that companies are reorganized versus liquidated, is specified.

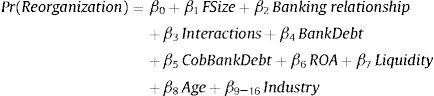

To independently contrast different hypotheses, the explanatory variables are introduced sequentially in the models. The general model specification is:

First, the firm size is introduced as a dummy variable, and subsequently, in the robustness analysis, a continuous variable (logarithm total assets) is considered. Banking relationship is approximated by the number of entities (NBank) or the bank size (BigBank or Big5Bank). In addition, two interaction variables between firm size and bank size are considered. Those variables, namely FSizeDxBigBank and FSizexDBig5Bank, adopt the value 1 if the company is an SME (not micro) and maintains relationships with the largest bank, or one of the five largest financial entities, respectively. The variable takes the value 0 if the company is a micro firm and/or if it does not have relations with one of the large financial institutions. All the models include the same control variables: Bank debt, CobBankDebt, ROA, Liquidity, Age and Industry. The estimation was performed using STATA 11 program.

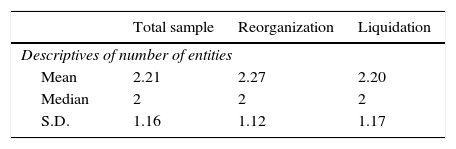

4Results4.1Descriptive analysisFirstly, it is worth noting that approximately 20% (124 of 622) of the companies in bankruptcy achieve an agreement with their creditors to continue operating. Related to banking relationships, as seen in Table 1, companies maintain relationships with, on average, two banks, although in reorganized companies that percentage is slightly higher than in liquidated ones.

Banking relationships of bankruptcy Spanish firms (%).

| Total sample | Reorganization | Liquidation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptives of number of entities | |||

| Mean | 2.21 | 2.27 | 2.20 |

| Median | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| S.D. | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.17 |

| Total sample (%) | Reorganization (%) | Liquidation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution of firms for number of entities | |||

| 1 | 33.92 | 31.45 | 34.54 |

| 2 | 28.62 | 28.23 | 28.71 |

| 3 | 24.76 | 25.00 | 24.70 |

| 4 | 8.84 | 12.10 | 8.03 |

| 5 | 2.73 | 3.23 | 2.61 |

| 6 | 0.80 | 0 | 1.00 |

| 7 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.40 |

| No. of firms | 622 | 124 | 498 |

On the other hand, about one third of companies maintain an exclusive relationship with their financial institution, with a low percentage of companies maintaining relationships with more than 5 entities. It can be observed that companies that maintain relations with between 3 and 5 banks are reorganized in a greater proportion, and this percentage is lower for companies with an exclusive relationship. Finally, there is no company with more than 3 relationships between reorganized companies.

Table 2 shows the variables that have been considered to identify banking relationships and the characteristics of companies in the sample, both at the aggregate level and considering the type of resolution, reorganization versus liquidation.

Differences in mean of banking relationships, firm characteristics and bankruptcy resolution.

| Total sample | Reorganization | Liquidation | Reorg. vs Liquid. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | Media | Media | T-test | |

| FSizeD | 59.80 | 72.58 | 56.62 | −3.2648*** |

| FSizeL | 3.47 | 3.62 | 3.43 | −3.4935*** |

| NBank | 2.21 | 2.27 | 2.20 | −0.6288 |

| BigBank | 30.38 | 41.12 | 27.71 | −2.9222*** |

| Big5Bank | 71.70 | 72.58 | 72.08 | −0.1093 |

| FSizeDxBigBank | 20.09 | 34.67 | 16.46 | −4.5974*** |

| FSizeDxBig5Bank | 44.37 | 56.45 | 41.36 | −3.0432*** |

| Bankdebt | 46.37 | 46.93 | 46.23 | −0.3012 |

| CobBankdebt | 26.52 | 41.12 | 22.89 | −4.1666*** |

| ROA | −15.14 | −7.54 | −17.03 | −2.6566*** |

| Liquidity | 1.58 | 1.26 | 1.66 | 1.0050 |

| Age | 1.19 | 1.15 | 1.20 | 1.6233* |

| No. of firms | 622 | 124 | 498 | |

Variables: FSizeD: dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium (assets higher 2 million euros and 0 if micro, less than or equal to two million asset); FSizeL: logarithm total assets; NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; FSizeDxBigBank: product of size and BigBank; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; FSizeDxBig5Bank: product of size and Big5Bank; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

First, the size of company is significantly higher in reorganized companies. Secondly, the average number of banks is similar in reorganized and liquidated firms. Thirdly, it is worth noting that only one of the three proxy variables of banking relationships, the representative dummy to operate with the largest bank, is significantly different in both groups, with a higher percentage in reorganized companies than in liquidated firms.

Regarding the interaction variables that relate the firm size and the bank size, it can be observed that the largest companies (SME) benefit from maintaining relations not only with the biggest one but with one of the five largest banks, too. Finally, reorganized companies are significantly more profitable and have more coverage of bank debt.

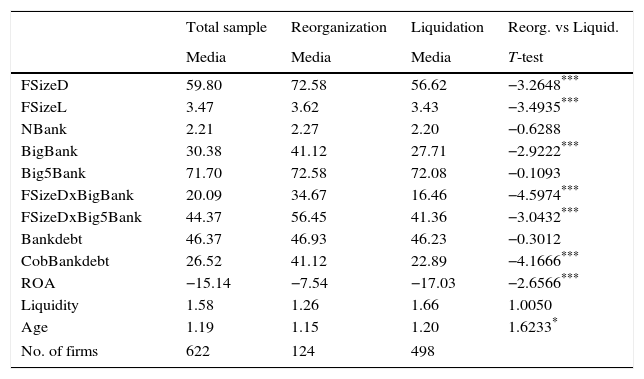

On the other hand, it is interesting to analyse the differences between micro and SME firms. As it can be observed in Table 3, for the whole of the sample, all the variables (except the coverage of bank debt) show significant differences between micro and SME firms. The average of the number of banks is bigger in the SME than micro firm. Furthermore, the percentage of firms that maintain relationships with the biggest bank and with one of the largest bank is higher in the SME than micro firms, too. Lastly, the SME firms have more bank debt, more profitability, more liquidity and less age.

Differences in mean of banking relationships, firm characteristics, bankruptcy resolution and firm size.

| All sample | Reorganization | Liquidation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | SME | T-test | Micro | SME | T-test | Micro | SME | T-test | |

| FSizeL | 2.95 | 3.82 | −32.7968*** | 2.97 | 3.86 | −13.5092*** | 2.95 | 3.80 | −29.4046*** |

| NBank | 1.86 | 2.45 | −6.3754*** | 1.61 | 2.52 | −4.2485*** | 1.90 | 2.43 | −5.0923*** |

| BigBank | 25.60 | 33.60 | −2.1318** | 23.53 | 47.77 | −2.4890*** | 25.92 | 29.07 | −0.7778 |

| Big5Bank | 69.20 | 74.19 | −1.3625* | 58.82 | 77.77 | −2.1322** | 70.83 | 73.05 | −0.5455 |

| Bankdebt | 38.79 | 51.46 | −6.8941*** | 34.35 | 51.68 | −3.8207*** | 39.49 | 51.39 | −5.8577*** |

| CobBankdebt | 27.20 | 26.07 | 0.3110 | 44.11 | 40.00 | 0.4126 | 24.53 | 21.63 | 0.7638 |

| ROA | −27.08 | −7.12 | −7.0842*** | −17.41 | −3.81 | −4.4043*** | −28.60 | −8.17 | −6.0038*** |

| Liquidity | 1.09 | 1.90 | −2.5351*** | 1.22 | 1.28 | −0.2833 | 1.08 | 2.10 | −2.6321*** |

| Age | 1.21 | 1.17 | 2.3009** | 1.26 | 1.11 | 2.7324** | 1.21 | 1.18 | 1.0197 |

| No. of firms | 250 | 372 | 34 | 90 | 216 | 282 | |||

Micro: firms with assets less than or equal to 2 million euros; SME: firms with assets higher than 2 million euros.

Variables: FSizeL: logarithm total assets; NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

T-test is computed micro versus SME.

Distinguishing between the two types of resolution, it is observed that in both groups, the number of banking relationships is higher in the SME firms than in micro ones, although the difference is more pronounced in the reorganized firms. Additionally, when the percentage of firms that works with the biggest bank or with one of the largest five ones is analysed, greater differences are observed between the micro and SME firms in the group of reorganized companies, while the results are more similar in the liquidated firms. Specifically, a 47.77% of the reorganized firms are SME, while only a 29% of SME is liquidated. The micro firms present around a 23–26% in both groups. In the same line, in reorganized firms, the percentage of firms that work with one of the largest five banks is greater in the SME firms than in micro ones, while it is similar in liquidated firms. Finally, regarding the firms characteristics, on average, the SME firms are more profitable, younger and have more liquidity than the micro firms in both groups.

Therefore, from the descriptive analysis, it can be deduced that the company size helps to explain the resolution of bankruptcies in Spain, and also exerts a moderating effect on the relationship between bank size and the probability of reorganization. On the other hand, the results also provide support to arguments concerning reputation, to the extent that operating with a large bank also favourably affects reorganization, particularly in SME companies rather than microenterprises. Finally, it has been detected that the size of financial institution also affects, especially operate with the largest Spanish financial institutions, to the chance that the company obtains an agreement with its creditors. However, these results should be compared after controlling for other variables that affect the likelihood of reorganization, for which a multivariate analysis is subsequently addressed.

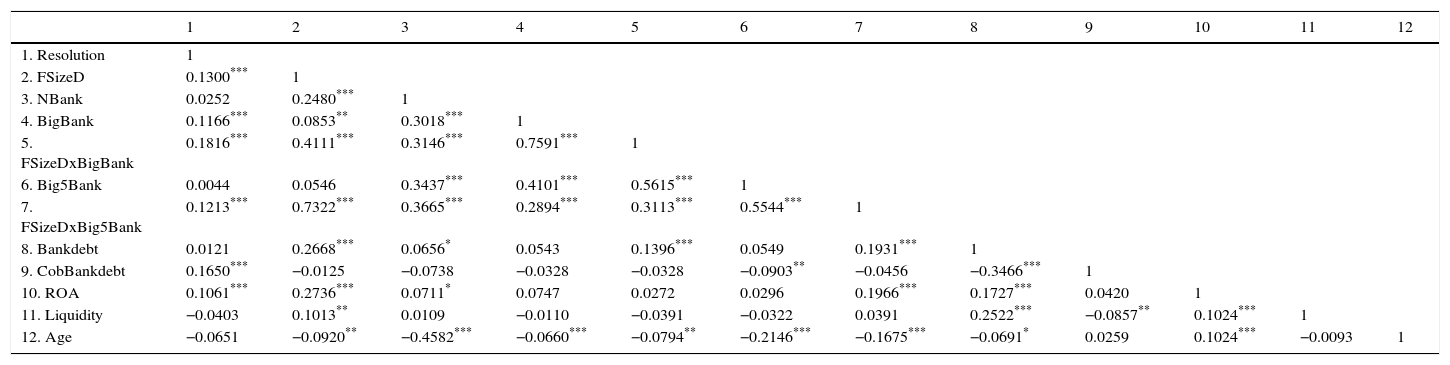

Before performing multivariate analysis, we analyse the possible existence of correlation between variables. This information is provided in Table 4, where it is possible to check for the absence of high correlations among the variables included together in the models (except those representing the interaction with size), which would indicate the absence of multicollinearity.

Correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Resolution | 1 | |||||||||||

| 2. FSizeD | 0.1300*** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 3. NBank | 0.0252 | 0.2480*** | 1 | |||||||||

| 4. BigBank | 0.1166*** | 0.0853** | 0.3018*** | 1 | ||||||||

| 5. FSizeDxBigBank | 0.1816*** | 0.4111*** | 0.3146*** | 0.7591*** | 1 | |||||||

| 6. Big5Bank | 0.0044 | 0.0546 | 0.3437*** | 0.4101*** | 0.5615*** | 1 | ||||||

| 7. FSizeDxBig5Bank | 0.1213*** | 0.7322*** | 0.3665*** | 0.2894*** | 0.3113*** | 0.5544*** | 1 | |||||

| 8. Bankdebt | 0.0121 | 0.2668*** | 0.0656* | 0.0543 | 0.1396*** | 0.0549 | 0.1931*** | 1 | ||||

| 9. CobBankdebt | 0.1650*** | −0.0125 | −0.0738 | −0.0328 | −0.0328 | −0.0903** | −0.0456 | −0.3466*** | 1 | |||

| 10. ROA | 0.1061*** | 0.2736*** | 0.0711* | 0.0747 | 0.0272 | 0.0296 | 0.1966*** | 0.1727*** | 0.0420 | 1 | ||

| 11. Liquidity | −0.0403 | 0.1013** | 0.0109 | −0.0110 | −0.0391 | −0.0322 | 0.0391 | 0.2522*** | −0.0857** | 0.1024*** | 1 | |

| 12. Age | −0.0651 | −0.0920** | −0.4582*** | −0.0660*** | −0.0794** | −0.2146*** | −0.1675*** | −0.0691* | 0.0259 | 0.1024*** | −0.0093 | 1 |

Variables: FSizeD: dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium (assets higher 2 million euros and 0 if micro, less than or equal to two million asset); NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; FSizeDxBigBank: product of dummy firm size and BigBank; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; FSizeDxBig5Bank: product of dummy firm size and Big5Bank; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

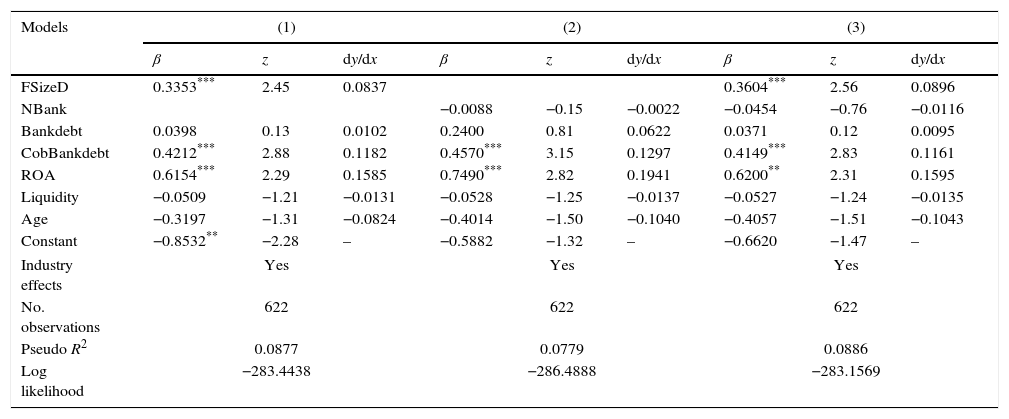

The testing of the hypotheses is performed in two stages. First, the hypothesis H1 is contrasted to H2, related to the impact of firm size and the number of banking relationships, over the probability that the company obtains an agreement with its creditors (reorganization) (models 1–3). Then, the H3 and H4 hypotheses are contrasted, concerning bank size (models 4–6). The results of models 1–3 are shown in Table 5. As can be observed, firm size is positive and significant, which indicates that larger (small and medium) enterprises are more likely to reorganize than smaller ones (micro). However, the number of banking relations is negative but not significant in models 2 and 3.8

Firm size, concentration and bankruptcy resolution. Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| FSizeD | 0.3353*** | 2.45 | 0.0837 | 0.3604*** | 2.56 | 0.0896 | |||

| NBank | −0.0088 | −0.15 | −0.0022 | −0.0454 | −0.76 | −0.0116 | |||

| Bankdebt | 0.0398 | 0.13 | 0.0102 | 0.2400 | 0.81 | 0.0622 | 0.0371 | 0.12 | 0.0095 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.4212*** | 2.88 | 0.1182 | 0.4570*** | 3.15 | 0.1297 | 0.4149*** | 2.83 | 0.1161 |

| ROA | 0.6154*** | 2.29 | 0.1585 | 0.7490*** | 2.82 | 0.1941 | 0.6200** | 2.31 | 0.1595 |

| Liquidity | −0.0509 | −1.21 | −0.0131 | −0.0528 | −1.25 | −0.0137 | −0.0527 | −1.24 | −0.0135 |

| Age | −0.3197 | −1.31 | −0.0824 | −0.4014 | −1.50 | −0.1040 | −0.4057 | −1.51 | −0.1043 |

| Constant | −0.8532** | −2.28 | – | −0.5882 | −1.32 | – | −0.6620 | −1.47 | – |

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| No. observations | 622 | 622 | 622 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0877 | 0.0779 | 0.0886 | ||||||

| Log likelihood | −283.4438 | −286.4888 | −283.1569 | ||||||

Variables: FSizeD: dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium (assets higher 2 million euros and 0 if micro, less than or equal to two million asset); NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

*Significant at 10%.

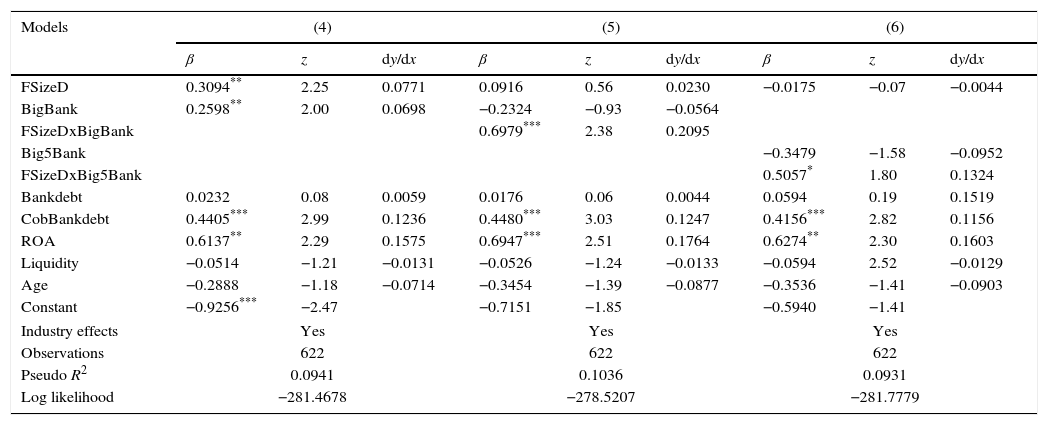

Regarding bank size, the results of the estimated models to test hypotheses 3 and 4 are presented in Table 6. In model 4, the dummy BigBank (largest of the Spanish banks) has been included. As can be seen, firm size has the positive sign observed in previous models. In addition, it is noteworthy that in this model, the variable representing banking relationship (BigBank) is significant and positive.

Firm size, bank size and bankruptcy resolution. Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (4) | (5) | (6) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| FSizeD | 0.3094** | 2.25 | 0.0771 | 0.0916 | 0.56 | 0.0230 | −0.0175 | −0.07 | −0.0044 |

| BigBank | 0.2598** | 2.00 | 0.0698 | −0.2324 | −0.93 | −0.0564 | |||

| FSizeDxBigBank | 0.6979*** | 2.38 | 0.2095 | ||||||

| Big5Bank | −0.3479 | −1.58 | −0.0952 | ||||||

| FSizeDxBig5Bank | 0.5057* | 1.80 | 0.1324 | ||||||

| Bankdebt | 0.0232 | 0.08 | 0.0059 | 0.0176 | 0.06 | 0.0044 | 0.0594 | 0.19 | 0.1519 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.4405*** | 2.99 | 0.1236 | 0.4480*** | 3.03 | 0.1247 | 0.4156*** | 2.82 | 0.1156 |

| ROA | 0.6137** | 2.29 | 0.1575 | 0.6947*** | 2.51 | 0.1764 | 0.6274** | 2.30 | 0.1603 |

| Liquidity | −0.0514 | −1.21 | −0.0131 | −0.0526 | −1.24 | −0.0133 | −0.0594 | 2.52 | −0.0129 |

| Age | −0.2888 | −1.18 | −0.0714 | −0.3454 | −1.39 | −0.0877 | −0.3536 | −1.41 | −0.0903 |

| Constant | −0.9256*** | −2.47 | −0.7151 | −1.85 | −0.5940 | −1.41 | |||

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Observations | 622 | 622 | 622 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0941 | 0.1036 | 0.0931 | ||||||

| Log likelihood | −281.4678 | −278.5207 | −281.7779 | ||||||

Variables: FSizeD: dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium (assets higher 2 million euros and 0 if micro, less than or equal to two million asset); NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; FSizeDxBigBank: product of size and BigBank; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; FSizeDxBig5Bank: product of size and Big5Bank; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

In model 5, the firm size and the BigBank are not significant, but the interaction between size and BigBank is significant and positive. Finally, the results of model 6, wherein the Big5Bank dummy is included, are similar to model 5, although the significance of the interaction between firm size and bank size is reduced, passing from 1% to 10%.9 The results of both models allow one to conclude that companies are more likely to reorganize if they maintain relationships with large banks, and this effect is enhanced when the relationship occurs with the largest bank and SMEs (not micro). This provides support to arguments concerning the reputation of financial institutions, which are more concerned with larger firms, whose visibility can have a greater effect on their reputation.

The control variables present similar results in all models. Thus, ROA is positive and significant, indicating that the most profitable companies are more likely to reorganize. Related to bank debt, it is noteworthy that the results show that the existence of collateral is more relevant to recover debt than the amount of the debt itself.

4.3Robustness analysisWith the aim of analysing the robustness of the results, the models have been re-estimated considering four additional analyses. First, it has been considerate a subsample in which were eliminated the firms that initially obtained an agreement with their creditors and then they were liquidated. Secondly, the dummy variable that represents the firm size has been replaced by the continuous variable (assets logarithm). Thirdly, some of the models have been re-estimated for each subsample of micro and SME firms, separately. Finally, audit has been considered as a proxy of asymmetric information, instead of the firm size.

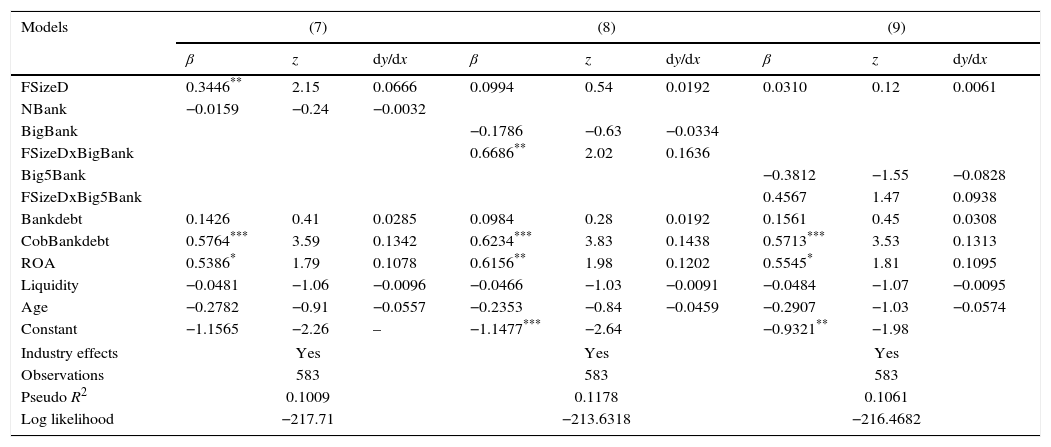

According to Sundgren (1998), in some cases, the liquidation of inefficient firms can be delayed, due to initial reorganization. Thus, many firms that emerge with a confirmed plan re-enter reorganization proceedings, or file for liquidation bankruptcy, within a few years. This author finds that 16 of 102 Finnish small- and mid-size firms that emerged from reorganization failed to comply with the plan within about one and a half years of confirmation. In the present work, according to the criterion used to define the resolution, some companies that initially obtained an agreement with their creditors, have subsequently been liquidated. This may be due to errors in the process of assessing the future viability of companies, or supervening situations that prevent the company's compliance with the agreement. To resolve this discrepancy, as robustness analysis, 39 companies that have moved from reorganization to liquidation are eliminated. So, the sub-sample is composed of 583 companies, of which 85 are rearranged, representing 14.58%. To do this, we proceed to estimate some of the models eliminating these companies to detect whether the results are affected by this issue. The results of the re-estimation of models 3, 5 and 6 are presented in Table 7. Thus, the results of the models 7 and 8 are similar in sign and significance to those initially obtained in models 3 and 5, respectively. However, in model 9 none of the three variables is significant, so that the consideration of the Big5 loses relevance. This is consistent with the comments made by comparing the statistical significance of the coefficient of this variable in model 6 with respect to model 5.

Robustness analysis (I). Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (7) | (8) | (9) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| FSizeD | 0.3446** | 2.15 | 0.0666 | 0.0994 | 0.54 | 0.0192 | 0.0310 | 0.12 | 0.0061 |

| NBank | −0.0159 | −0.24 | −0.0032 | ||||||

| BigBank | −0.1786 | −0.63 | −0.0334 | ||||||

| FSizeDxBigBank | 0.6686** | 2.02 | 0.1636 | ||||||

| Big5Bank | −0.3812 | −1.55 | −0.0828 | ||||||

| FSizeDxBig5Bank | 0.4567 | 1.47 | 0.0938 | ||||||

| Bankdebt | 0.1426 | 0.41 | 0.0285 | 0.0984 | 0.28 | 0.0192 | 0.1561 | 0.45 | 0.0308 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.5764*** | 3.59 | 0.1342 | 0.6234*** | 3.83 | 0.1438 | 0.5713*** | 3.53 | 0.1313 |

| ROA | 0.5386* | 1.79 | 0.1078 | 0.6156** | 1.98 | 0.1202 | 0.5545* | 1.81 | 0.1095 |

| Liquidity | −0.0481 | −1.06 | −0.0096 | −0.0466 | −1.03 | −0.0091 | −0.0484 | −1.07 | −0.0095 |

| Age | −0.2782 | −0.91 | −0.0557 | −0.2353 | −0.84 | −0.0459 | −0.2907 | −1.03 | −0.0574 |

| Constant | −1.1565 | −2.26 | – | −1.1477*** | −2.64 | −0.9321** | −1.98 | ||

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Observations | 583 | 583 | 583 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1009 | 0.1178 | 0.1061 | ||||||

| Log likelihood | −217.71 | −213.6318 | −216.4682 | ||||||

Variables: FSizeD: dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm is categorized as small or medium (assets higher 2 million euros and 0 if micro, less than or equal to two million asset); NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; FSizeDxBigBank: product of firm size dummy and BigBank; Big5Bank: dummy=1 if the firm maintains relations with one of the five largest banks; FSizeDxBig5Bank: product of firm size dummy and Big5Bank; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

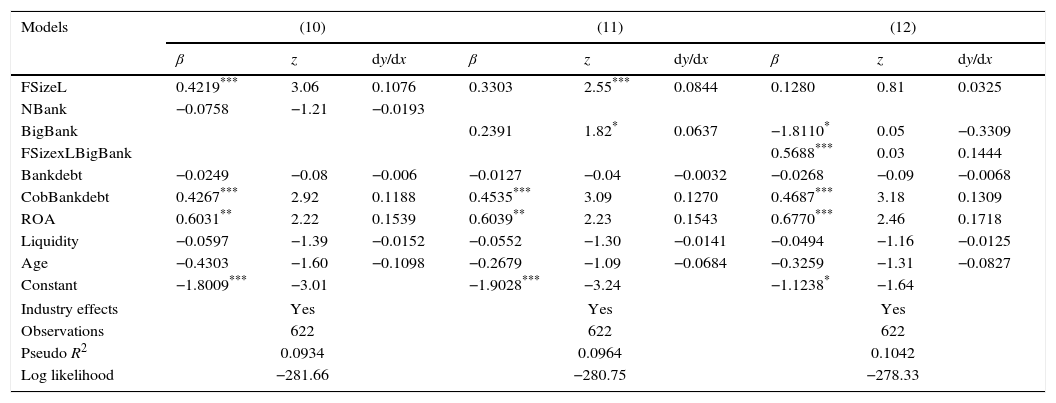

The results in which the assets logarithm is used as a proxy of the size are presented in Table 8. The results of the model 10 that takes into account the size of the firm and the number of banking relationships are similar to model 3, where the firm size is positive and significant and the number of banks is not significant. In model 11, firm size and the dummy variable about maintaining relationships with the biggest bank are included. Both of them are positive and significant, as in model 4. Finally, the model 12 includes the interaction variable between the firm size and the variable about the biggest bank, and the results are the same that in model 5.10

Robustness analysis (II). Firm size: logarithm total assets. Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (10) | (11) | (12) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| FSizeL | 0.4219*** | 3.06 | 0.1076 | 0.3303 | 2.55*** | 0.0844 | 0.1280 | 0.81 | 0.0325 |

| NBank | −0.0758 | −1.21 | −0.0193 | ||||||

| BigBank | 0.2391 | 1.82* | 0.0637 | −1.8110* | 0.05 | −0.3309 | |||

| FSizexLBigBank | 0.5688*** | 0.03 | 0.1444 | ||||||

| Bankdebt | −0.0249 | −0.08 | −0.006 | −0.0127 | −0.04 | −0.0032 | −0.0268 | −0.09 | −0.0068 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.4267*** | 2.92 | 0.1188 | 0.4535*** | 3.09 | 0.1270 | 0.4687*** | 3.18 | 0.1309 |

| ROA | 0.6031** | 2.22 | 0.1539 | 0.6039** | 2.23 | 0.1543 | 0.6770*** | 2.46 | 0.1718 |

| Liquidity | −0.0597 | −1.39 | −0.0152 | −0.0552 | −1.30 | −0.0141 | −0.0494 | −1.16 | −0.0125 |

| Age | −0.4303 | −1.60 | −0.1098 | −0.2679 | −1.09 | −0.0684 | −0.3259 | −1.31 | −0.0827 |

| Constant | −1.8009*** | −3.01 | −1.9028*** | −3.24 | −1.1238* | −1.64 | |||

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Observations | 622 | 622 | 622 | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0934 | 0.0964 | 0.1042 | ||||||

| Log likelihood | −281.66 | −280.75 | −278.33 | ||||||

Variables: FSizeL: logarithm total assets; NBank: number of banking relationships; BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; FSizeLxBigBank: product of logarithm total assets and BigBank; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

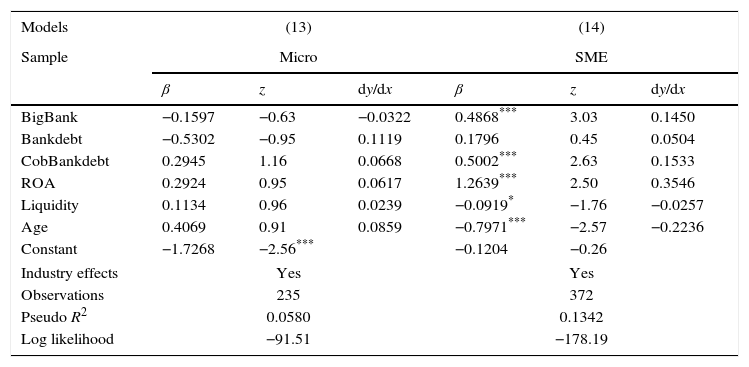

Considering the distinction between micro and SME firms, the results about the number of banking relationships and about maintaining a relationship with one of the largest banks are not significant (unreported results), like in the initial models. However, maintaining a relationship with the biggest bank (Table 9) is positive and significant in the SME firms (model 14) but not in micro firms (model 13). That result confirms the previous one in which the interaction between the firm size and BigBank was positive.

Robustness analysis (III). Samples: micro and SME. Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (13) | (14) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Micro | SME | ||||

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| BigBank | −0.1597 | −0.63 | −0.0322 | 0.4868*** | 3.03 | 0.1450 |

| Bankdebt | −0.5302 | −0.95 | 0.1119 | 0.1796 | 0.45 | 0.0504 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.2945 | 1.16 | 0.0668 | 0.5002*** | 2.63 | 0.1533 |

| ROA | 0.2924 | 0.95 | 0.0617 | 1.2639*** | 2.50 | 0.3546 |

| Liquidity | 0.1134 | 0.96 | 0.0239 | −0.0919* | −1.76 | −0.0257 |

| Age | 0.4069 | 0.91 | 0.0859 | −0.7971*** | −2.57 | −0.2236 |

| Constant | −1.7268 | −2.56*** | −0.1204 | −0.26 | ||

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Observations | 235 | 372 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.0580 | 0.1342 | ||||

| Log likelihood | −91.51 | −178.19 | ||||

Variables: BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

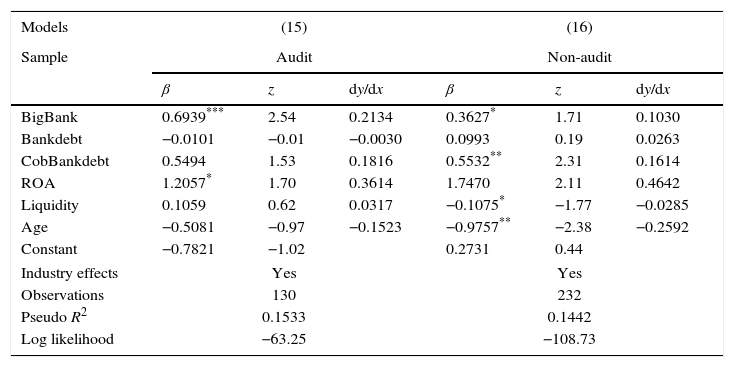

Lastly, regarding audit, only a 24% of the firms have audited annual accounts, being mainly SME firms. For this reason, the models have been re-estimated only for this group. Firstly, a dummy variable that adopts the value one if the firm is audited and zero otherwise, has been introduced in the models; this variable is not significant (unreported results). Secondly, the models have been re-estimated for audited and non-audited firms, separately. Among the representative variables of the banking relationships, only BigBank is significant, being positive in audited and non-audited firms (Table 10). However, the coefficient and the level of significance are greater in audited firms (model 15) than in non-audited (model 16). These results mean that if the SME firms maintain relationships with the biggest bank, the likelihood of reorganization is greater when the annual accounts are audited.11

Robustness analysis (IV). Sample SME: audited and non-audited. Dependent variable: resolution (reorganization=1, liquidation=0). Estimation method: probit.

| Models | (15) | (16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Audit | Non-audit | ||||

| β | z | dy/dx | β | z | dy/dx | |

| BigBank | 0.6939*** | 2.54 | 0.2134 | 0.3627* | 1.71 | 0.1030 |

| Bankdebt | −0.0101 | −0.01 | −0.0030 | 0.0993 | 0.19 | 0.0263 |

| CobBankdebt | 0.5494 | 1.53 | 0.1816 | 0.5532** | 2.31 | 0.1614 |

| ROA | 1.2057* | 1.70 | 0.3614 | 1.7470 | 2.11 | 0.4642 |

| Liquidity | 0.1059 | 0.62 | 0.0317 | −0.1075* | −1.77 | −0.0285 |

| Age | −0.5081 | −0.97 | −0.1523 | −0.9757** | −2.38 | −0.2592 |

| Constant | −0.7821 | −1.02 | 0.2731 | 0.44 | ||

| Industry effects | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Observations | 130 | 232 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1533 | 0.1442 | ||||

| Log likelihood | −63.25 | −108.73 | ||||

Variables: BigBank: dummy=1 if the firm has relationships with the largest banks; Bankdebt: bank debt/total debt; CobBankdebt: dummy=1 if the ratio of noncurrent assets and bank debt is greater than 1; ROA: earnings before interest and tax divided by the total assets; Liquidity: current asset/current liabilities; Age: logarithm of number of years since the firm creation.

dy/dx: marginal effects.

In sum, the robustness analysis confirms the previous results regarding the non-significance of the number of relationships in the bankruptcy resolution, but the convenience of operating with the biggest bank. In addition, the analysis has shown that the relationship is only significant in the SME firms, and especially in the case of audited firms.

5Discussion of results and conclusionsIn the present study, we analyse the incidence of size and banking relationships in the resolution of financial distress, particularly for companies that are filing for the legal process of bankruptcy, as opposed to other firms that try to resolve insolvency through private negotiation. In this regard, it should be noted that Spain is a country with a low insolvency rate in comparison to neighbouring countries. This fact is partly due to the limited judicial efficiency in resolving these processes, whose long duration considerably increases the costs, such as the greater efficiency of the foreclosure process (García-Posada and Mora-Sanguineti, 2013).

Based on the arguments provided by the theory of asymmetric information, five hypotheses are raised, which, on the one hand, try to reflect the impact of size and banking relationships and, on the other, the interaction between them. In this sense, it is predicted that larger companies are more likely to be reorganized because of their smaller information asymmetries. Moreover, fewer bank relationships can promote reorganization because coordination problems are reduced. In addition, larger banks could favour the reorganization of companies in bankruptcy to avoid damaging their own reputation. Finally, it is proposed that company size may have a moderating effect on these relationships.

The empirical study is conducted on a sample of 622 micro, small and medium bankrupt companies that entered bankruptcy in 2010, and for whom bankruptcies have been resolved by December 2014. To our knowledge, this is the one of the first studies that analyses the impact of banking relationships on bankruptcy resolution, in which it is considered the moderating effect of the firm size, and especially the bank size. In summary, the results indicate that, in general, size affects the probability of reorganization, while the number of banking relations does not. One of the main contributions of this work is the influence of bank size on bankruptcy resolution, revealing a reputation effect of large financial institutions that is enhanced in the event that the debtor is a company of a certain size, given its greater visibility. Therefore, the results support hypotheses 1 and 3, concerning company size and bank size, and hypothesis 4, which raises the interaction between company size and concentration of banking relationships and the interaction between company size and bank size. Those results are confirmed when different size proxies are considered, and also when the models are estimated for each subsample based on the size.

Included among the few studies that have analysed the incidence of banking relationships with the resolution of bankruptcy are Simishu (2012) and Rosenfeld (2014). The first finds that small banks enhance Japanese small firms’ recovery rate from financial distress. Rosenfeld (2014), in his study on US publicly traded firms, finds a positive effect on firm emergence from distress when the firm has five or fewer entities and when it works with a small bank. Therefore, the results obtained for Spanish bankruptcy firms do not coincide with those obtained by the abovementioned works, which can be related with the sample characteristics, with the different financial systems in their countries as well as with different levels of protection of the rights of creditors.

Finally, this paper presents a limitation arising from the information available on banking relationships. In this sense, obtaining additional information provided by the SABI database would require a survey that is virtually impossible because many of the companies have been liquidated, significantly reducing the size of the sample.

The authors wish to express their gratitude for its help to Cátedra la Caixa de Estudios Financieros y Bancarios in the Universidad of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

For example, French “Redressement Judiciaries” or US Chapter 11 are debtor-friendly and a British Administration or Voluntary Arrangement is creditor-oriented.

See articles 90–92 of the bankruptcy proceeding Law.

Included among the studies that use SABI database to obtain information about relationships banking are Montoriol (2006) and Gill de Albornoz and Illueca (2007).

This Recommendation also sets the number of employees, although this has not been considered because this data are unavailable for all companies in the sample.

This criterion is followed by Van Hemmen in the bankruptcy statistical yearbook published since 2007 by the Association of Registrars.

This author ranks all the distressed lender organizations’ assets and uses an indicator to denote whether the lending organization is in the smallest ten percent.

The data of these entities have been taken from the report Balances of Bank of Spain, December 2010, published by the Spanish Banking Association (AEB) and Spanish Confederation of Savings Banks (CECA). In billions of euros, the assets of these entities are: Santander: 429, BBVA: 392, la Caixa: 269, Cajamadrid: 182 and Popular: 130.

Models 2 and 3 are re-estimated by changing the variable number of bank for the dummy variable OneBank, which adopts the value 1 if the firm operates with only one bank. The results, not reports, are similar to those obtained in models 2 and 3, respectively, and the new variable is not significant.

A similar model 4 has been estimated, considering the variable Big5Bank (without the interaction with size), although it is not significant. Results non-reported.

Model 6 has been also re-estimated and the interaction variable between the firm size and the variable Big5Bank is not significant (in the model 6 its significance was 10%). Unreported results.

The models have been also re-estimated including the audit dummy variable as control variable and the results don not change (unreported results).