Vacunas COVID-19: desarrollo y práctica - COVID-19 vaccines: development and practice

Más datosIndonesia has not met its vaccination rate target, falling short of 25% in 2021. This study aims to assess all the contributing factors towards vaccine acceptance, hesitance, and refusal in a single vaccination center in Jambi, Indonesia.

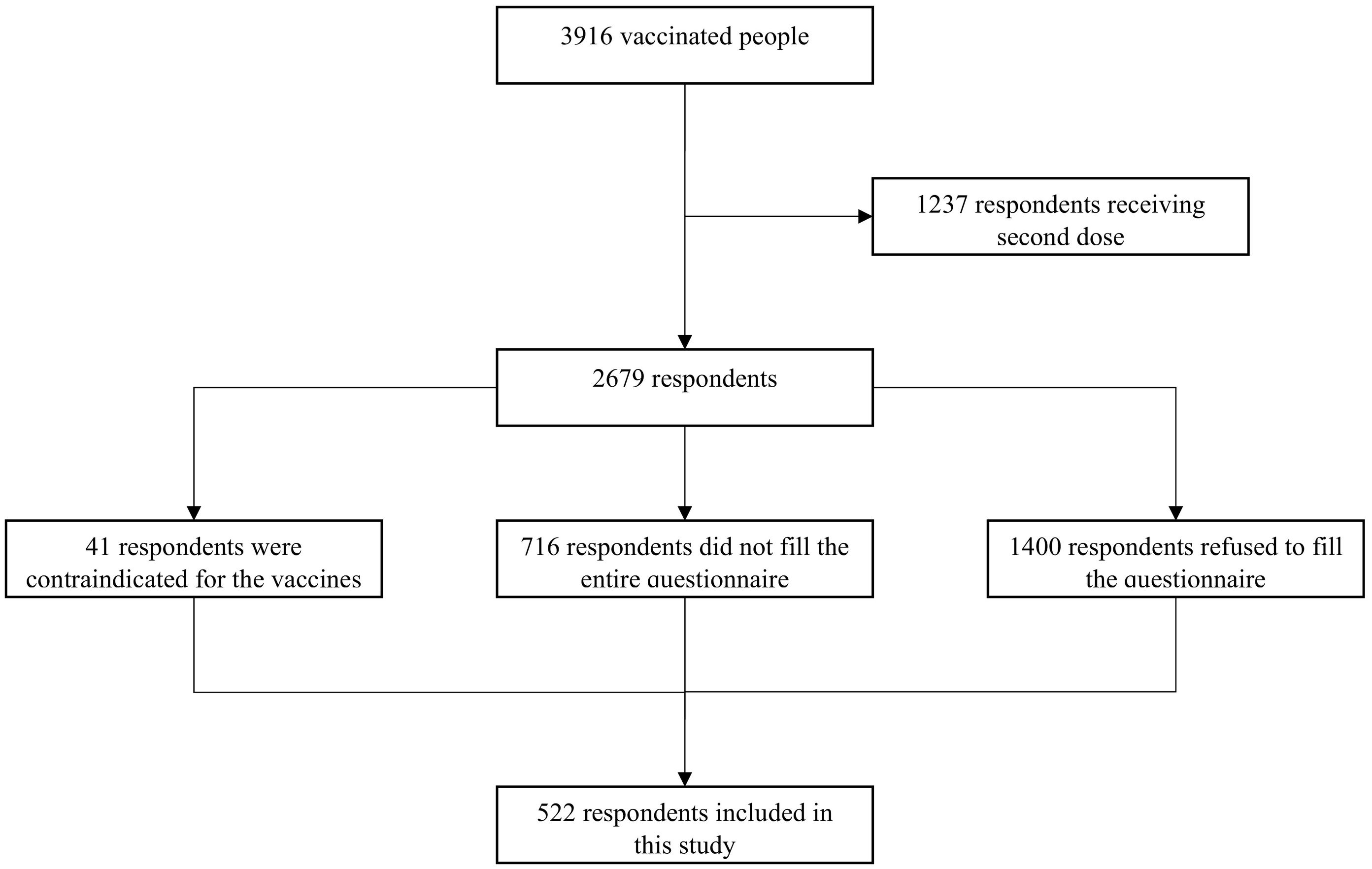

Materials and methodsWe collected primary data from respondents directly through a structured questionnaire. This was a cross-sectional study with total sampling. We included adults vaccinated for the first dose with CoronaVac in Puskesmas Putri Ayu. The data was collected between March 15th and June 3rd, 2021. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was done to analyse the predictive models.

ResultsThere are 522 respondents included in this study. Nearly half of the respondents are male (52.1%) and mostly in the age category of 36–45 years old (21.1%). A total of 443 respondents (84.9%) are “vaccine acceptance,” while the rest constitutes “vaccine hesitance and refusal.” Multivariate analysis reveals that respondents who obtain permission from work or school to get vaccinated are more likely to be “vaccine acceptance” with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.76 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–2.91; p-value 0.025), and respondents with ≥2 comorbidities are less likely to be “vaccine acceptance” with an OR of 0.09 (95% CI 0.01–0.64; p-value 0.015).

ConclusionsThere is a high vaccine acceptance in this study. Difficulties in getting a work permit and the presence of ≥2 comorbidities decrease the willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

Indonesia no ha alcanzado su objetivo de tasa de vacunación, por debajo del 25% en 2021. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar todos los factores que contribuyen a la aceptación, la vacilación y el rechazo de la vacuna en un solo centro de vacunación en Jambi, Indonesia.

Materiales y métodosrecopilamos datos primarios de los encuestados directamente a través de un cuestionario estructurado. Este fue un estudio transversal con muestreo total. Se incluyeron adultos vacunados para la primera dosis con CoronaVac en Puskesmas Putri Ayu. Los datos se recopilaron entre el 15 de marzo y el 3 de junio de 2021. Se realizó un análisis de regresión logística multivariante para analizar los modelos predictivos.

ResultadosHay 522 encuestados incluidos en este estudio. Casi la mitad de los encuestados son hombres (52,1%) y la mayoría se encuentran en la categoría de edad de 36 a 45 años (21,1%). Un total de 443 encuestados (84,9%) son “aceptación de la vacuna”, mientras que el resto constituye “vacilación y rechazo a la vacuna”. El análisis multivariado revela que los encuestados que obtienen permiso del trabajo o la escuela para vacunarse tienen más probabilidades de “aceptar la vacuna” con una razón de probabilidad (OR) de 1,76 (intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 1,08-2,91; valour de p 0,025), y los encuestados con ≥2 comorbilidades tienen menos probabilidades de “aceptar la vacuna” con un OR de 0,09 (IC del 95%: 0,01-0,64; valour de p 0,015).

ConclusionesExiste una alta aceptación de la vacuna en este estudio. Las dificultades para obtener un permiso de trabajo y la presencia de ≥ 2 comorbilidades disminuyen la disposición a vacunarse contra el COVID-19.

Vaccination has been touted as a “game-changer” that will help the world return to the “new normal” amid the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Currently, vaccination status has been implemented nationally in Indonesia and internationally as permission to participate in public activities such as travelling, entering communal spaces (e.g., mall or attending a concert), and going back to work.2,3

Although it has been established that COVID-19 vaccines are relatively safe,4–6 this finding is not widely available when vaccines are freshly distributed. Coupled with misleading information being widespread in the media and scepticism around how fast the COVID-19 vaccine is approved, the number of people being hesitant or even refusing to get a jab skyrockets.7,8

By the end of 2021, the government had hoped to have vaccinated around 67% of Indonesians.9 However, by December 31st 2021, 58.57% of Indonesians had received at least one shot, while only 41.26% of Indonesians were fully vaccinated with two doses.10 The COVID-19 vaccination effort is being slowed by a lack of competent medical personnel in rural locations, psychological issues, cold-chain storage and distribution challenges, and budgetary issues.11–13 However, people who are unwilling to be vaccinated or reject vaccines constitute the major issue.14

Vaccine hesitance and refusal have been observed worldwide, ranging from lay people to medical personnel.15–17 In November 2020, the World Health Organisation (WHO), the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia, and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) released a report. The results found that 64.8% of the 112,888 Indonesians polled were willing to be vaccinated, 7.6% refused all vaccines, and 27.6% were undecided.18 Therefore, it is paramount to assess the possible factors contributing to the high number of vaccine hesitance and vaccine refusal. By converting those hesitant about getting a vaccine, Indonesia could increase its vaccination rate.19

This study aims to assess all the contributing factors towards vaccine acceptance, vaccine hesitance, and refusal in a single vaccination center in Jambi, Indonesia. Based on the national survey, Jambi has one of the lowest vaccine acceptance rates of any city in Indonesia.18 As a result, the findings of this study may shed light on the reasons for poor vaccination acceptance rates.

MethodsWe collected primary data from respondents directly through a structured questionnaire. This was a cross-sectional study with total population sampling. This type of sampling is a sort of purposive sampling in which the entire population of interest (i.e., a group of people with the same trait) is researched. The questionnaire consisted of demographic data collection, such as age, sex, ethnicity, religion, marital status, comorbidities, highest education attained, income, health insurance, history of mental disorders, and smoking status. This questionnaire is self-administered, and if respondents were not clear with certain items, they could ask the field workers directly. There were several COVID-19-related questions such as previous exposures or any close contact with COVID-19 patients (yes/no/not sure), the impact of COVID-19 on income (increased/decreased/no change), whether respondents have experienced COVID-19-related symptoms (yes/no) and any COVID-19 testing that had been done (yes/no). We also collected data on height and weight before administering vaccines to calculate body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure to screen for hypertension. The Asia-Pacific classification of BMI would be used to classify BMI.20

We included adults (> 18 years) who were vaccinated with CoronaVac (Sinovac Life Sciences, Beijing, China) in Puskesmas Putri Ayu, one of the biggest Puskesmas in Jambi city, Indonesia. Puskesmas are government-mandated community health clinics in Indonesia promoting primary prevention. We chose Puskesmas Putri Ayu as our study site because Puskesmas was the first and only institution to administer COVID-19 vaccines. Being the biggest Puskesmas, this meant that there would be a larger vaccination catchment area compared to other Puskesmas. Our Puskesmas administered vaccines daily and citizens willing to be vaccinated would come to our Puskesmas. Participants were recruited while waiting to be vaccinated. The data was collected between March 15th and June 3rd 2021. The COVID-19 vaccinations were carried out in four phases, where our study period coincided with the second phase of vaccination. The targeted population for this phase was public service officers and the elderly (≥ 60 years old).21 However, we experienced a lot of unused doses on the field for various reasons such as refusal, not showing up, or contraindicated for the jab. In order to mitigate the number of doses potentially going to waste, residents nearby the Puskesmas were contacted to get the vaccine jab.

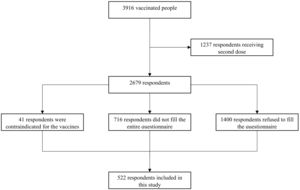

Our exclusion criteria were broadly categorised into three: refusal to participate in the study for any reason, contraindicated to COVID-19 vaccine administration, and receiving the second vaccine jab. We initially followed the recommendation of the Indonesian Society of Internal Medicine (issued on March 18th 2021), which was the first institution to recommend who could be vaccinated.22 Therefore, pregnant women and children were not included in this study as the recommendations to vaccinate these populations were announced on June 22nd 2021, and November 2nd 2021, respectively.23,24 Patients with primary immunodeficiency, acute and active infections (including SARS-CoV-2 infections or 3 months post-infection), blood pressure of ≥180/110 mmHg, unstable or uncontrolled chronic conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or heart failure, and those with Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, and Loss of weight (FRAIL) score of >2 were contraindicated to COVID-19 vaccination and hence excluded from this study.22

According to the Indonesian Ministry of Health, income was divided into five categories. Poor people had monthly household expenses of less than Rp 1416,000 (~$99); vulnerable people had monthly household expenses of between Rp 1416,000 and Rp 2,128,000 (~$99–$148); aspiring middle-class people had monthly household expenses of between Rp 2,128,001 and Rp 4800,000 (~$148 to $334); middle-class people had monthly household expenses of between Rp 4800,001 and Rp 24,000,000 (~$334 to $1671), and upper-class people had monthly household expenses above Rp 24,000,000 (~$1671).18 Respondents were divided into groups according to their stance on COVID-19 immunisation. We also asked whether respondents obtained permission from their upper management or teachers to be vaccinated that day. The reasoning behind this question was that schools or workplaces sometimes do not accept absence from work or schools just to be vaccinated. Therefore, this might affect one's acceptance of vaccination. Respondents were grouped as “vaccine acceptance” if they replied yes to the question “Are you sure that you are ready to be vaccinated before arriving at Puskesmas Putri Ayu?”, “vaccine refusal” if they answered no, and “vaccine hesitance” if they answered maybe.12

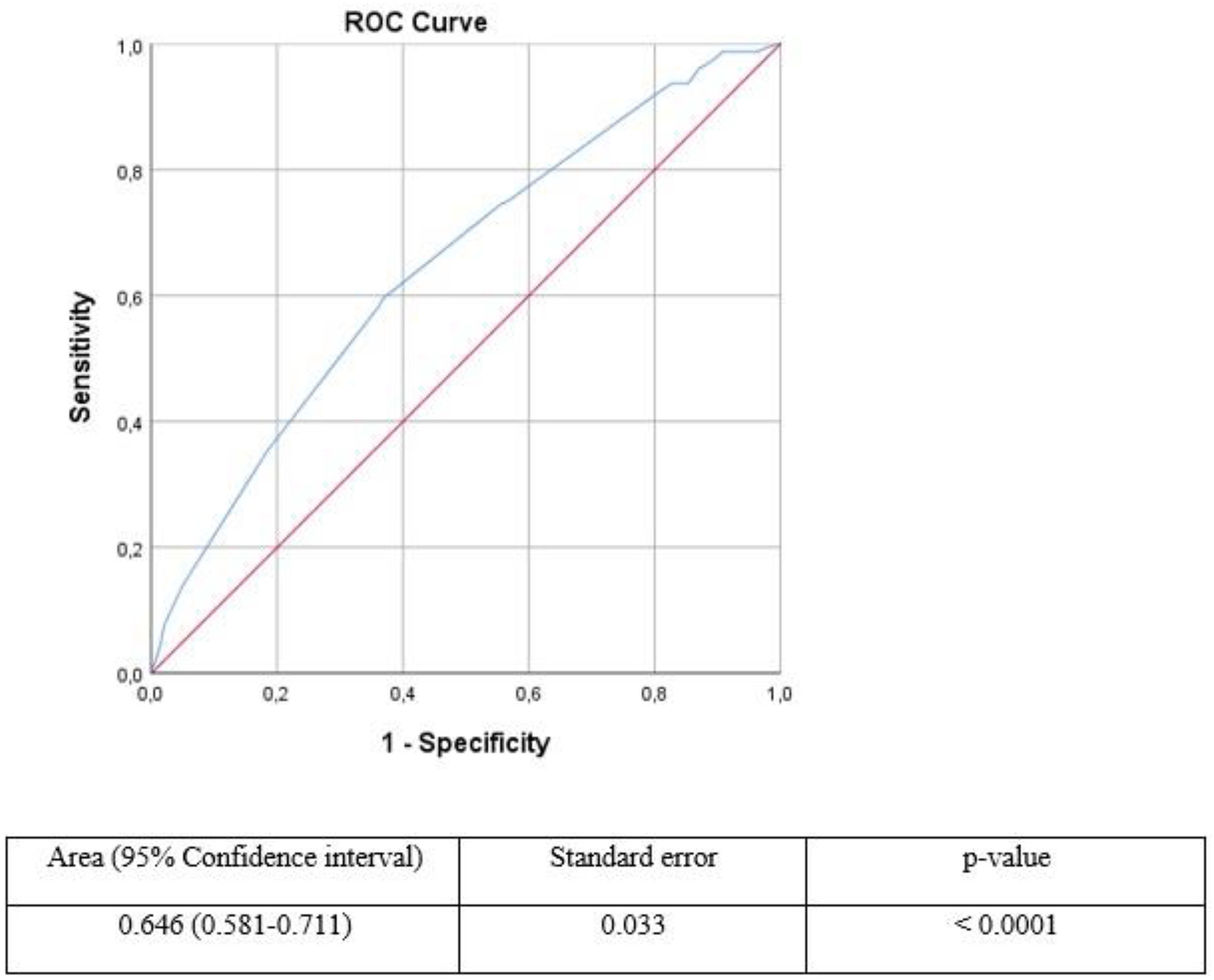

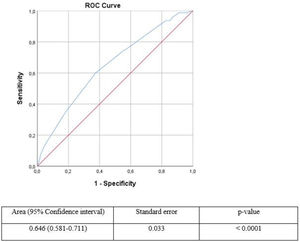

IBM SPSS 26.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, 2019) was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check for normality, and if the p-value was greater than 0.05, the data exhibited a normal distribution. The mean and standard deviation implied that the data were regularly distributed, whereas the median and range implied that the data were not. Bivariate analysis was performed using the chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to obtain a prediction model with the least confoundings. The receiver operating curve (ROC) and the Hosmer–Lemeshow test would be used to examine the performance of our final prediction findings for discrimination and calibration (goodness of fit), respectively. The ROC will calculate the area under the curve (AUC). An AUC of 1.0 correlates to a perfect result, >0.9 indicates a high accuracy, 0.7–0.9 indicates moderate accuracy, 0.5–0.7 indicates low accuracy, and 0.5 indicates that the results are caused by chance.25 A p-value of >0.05 from the Hosmer-Lemeshow test would indicate a good calibration.26

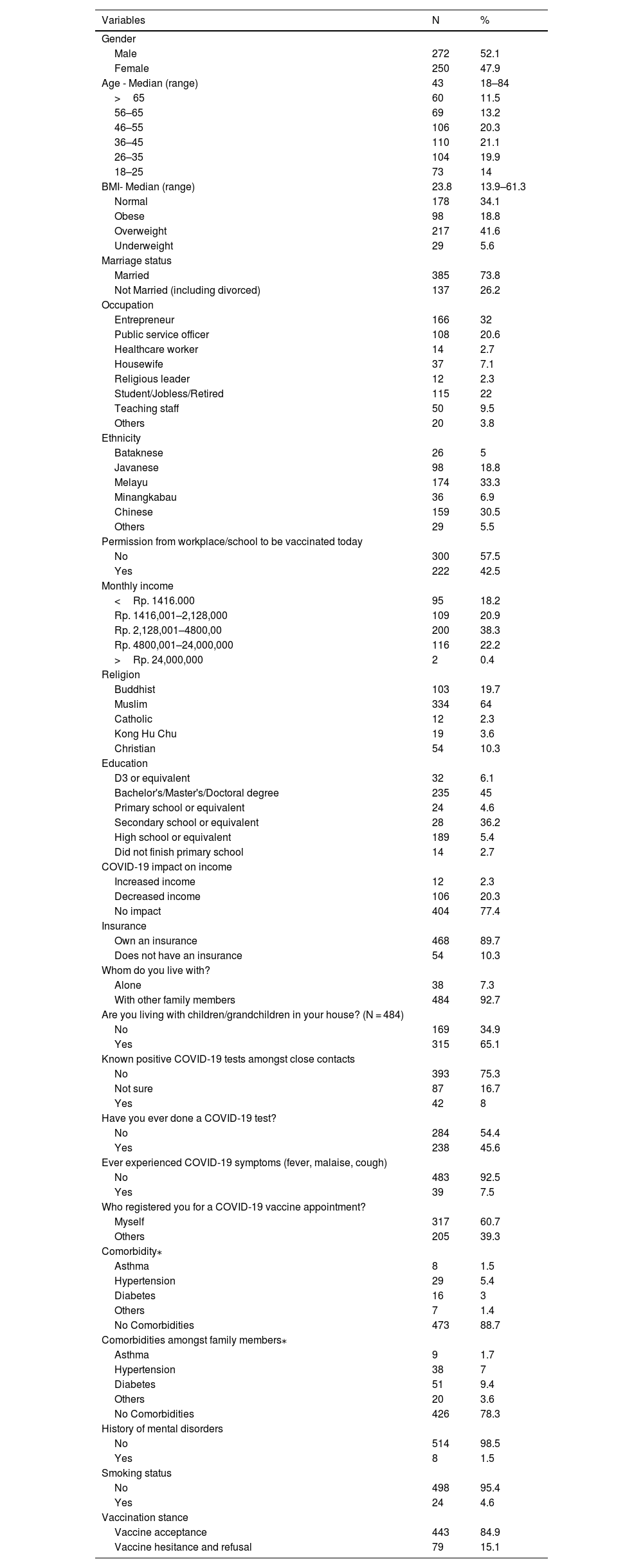

ResultsThere are 522 respondents included in this study (Fig. 1). A majority of our respondent is male (52.1%) and mostly in the age category of 36–45 years old (21.1%) (Table 1). The median BMI falls under the overweight category with 23.8 (13.9–61.3), with 217 respondents (41.6%) belonging to the overweight group. The aspiring middle class dominates with 200 respondents (38.3%) and mostly report no changes in income (77.4%) due to the pandemic. Muslims (64%) and Melayu (33.3%) are our respondents' most common religion and ethnicity, respectively.

Demographics of respondents.

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 272 | 52.1 |

| Female | 250 | 47.9 |

| Age - Median (range) | 43 | 18–84 |

| >65 | 60 | 11.5 |

| 56–65 | 69 | 13.2 |

| 46–55 | 106 | 20.3 |

| 36–45 | 110 | 21.1 |

| 26–35 | 104 | 19.9 |

| 18–25 | 73 | 14 |

| BMI- Median (range) | 23.8 | 13.9–61.3 |

| Normal | 178 | 34.1 |

| Obese | 98 | 18.8 |

| Overweight | 217 | 41.6 |

| Underweight | 29 | 5.6 |

| Marriage status | ||

| Married | 385 | 73.8 |

| Not Married (including divorced) | 137 | 26.2 |

| Occupation | ||

| Entrepreneur | 166 | 32 |

| Public service officer | 108 | 20.6 |

| Healthcare worker | 14 | 2.7 |

| Housewife | 37 | 7.1 |

| Religious leader | 12 | 2.3 |

| Student/Jobless/Retired | 115 | 22 |

| Teaching staff | 50 | 9.5 |

| Others | 20 | 3.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Bataknese | 26 | 5 |

| Javanese | 98 | 18.8 |

| Melayu | 174 | 33.3 |

| Minangkabau | 36 | 6.9 |

| Chinese | 159 | 30.5 |

| Others | 29 | 5.5 |

| Permission from workplace/school to be vaccinated today | ||

| No | 300 | 57.5 |

| Yes | 222 | 42.5 |

| Monthly income | ||

| <Rp. 1416.000 | 95 | 18.2 |

| Rp. 1416,001–2,128,000 | 109 | 20.9 |

| Rp. 2,128,001–4800,00 | 200 | 38.3 |

| Rp. 4800,001–24,000,000 | 116 | 22.2 |

| >Rp. 24,000,000 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Religion | ||

| Buddhist | 103 | 19.7 |

| Muslim | 334 | 64 |

| Catholic | 12 | 2.3 |

| Kong Hu Chu | 19 | 3.6 |

| Christian | 54 | 10.3 |

| Education | ||

| D3 or equivalent | 32 | 6.1 |

| Bachelor's/Master's/Doctoral degree | 235 | 45 |

| Primary school or equivalent | 24 | 4.6 |

| Secondary school or equivalent | 28 | 36.2 |

| High school or equivalent | 189 | 5.4 |

| Did not finish primary school | 14 | 2.7 |

| COVID-19 impact on income | ||

| Increased income | 12 | 2.3 |

| Decreased income | 106 | 20.3 |

| No impact | 404 | 77.4 |

| Insurance | ||

| Own an insurance | 468 | 89.7 |

| Does not have an insurance | 54 | 10.3 |

| Whom do you live with? | ||

| Alone | 38 | 7.3 |

| With other family members | 484 | 92.7 |

| Are you living with children/grandchildren in your house? (N = 484) | ||

| No | 169 | 34.9 |

| Yes | 315 | 65.1 |

| Known positive COVID-19 tests amongst close contacts | ||

| No | 393 | 75.3 |

| Not sure | 87 | 16.7 |

| Yes | 42 | 8 |

| Have you ever done a COVID-19 test? | ||

| No | 284 | 54.4 |

| Yes | 238 | 45.6 |

| Ever experienced COVID-19 symptoms (fever, malaise, cough) | ||

| No | 483 | 92.5 |

| Yes | 39 | 7.5 |

| Who registered you for a COVID-19 vaccine appointment? | ||

| Myself | 317 | 60.7 |

| Others | 205 | 39.3 |

| Comorbidity⁎ | ||

| Asthma | 8 | 1.5 |

| Hypertension | 29 | 5.4 |

| Diabetes | 16 | 3 |

| Others | 7 | 1.4 |

| No Comorbidities | 473 | 88.7 |

| Comorbidities amongst family members⁎ | ||

| Asthma | 9 | 1.7 |

| Hypertension | 38 | 7 |

| Diabetes | 51 | 9.4 |

| Others | 20 | 3.6 |

| No Comorbidities | 426 | 78.3 |

| History of mental disorders | ||

| No | 514 | 98.5 |

| Yes | 8 | 1.5 |

| Smoking status | ||

| No | 498 | 95.4 |

| Yes | 24 | 4.6 |

| Vaccination stance | ||

| Vaccine acceptance | 443 | 84.9 |

| Vaccine hesitance and refusal | 79 | 15.1 |

Our respondents are mostly married (73.8%), live together with other family members (92.7%), especially with their children or grandchildren (65.1%). Most of our respondents are highly educated, as 235 respondents (45%) have a minimum of Bachelor's degrees. This study finds that 468 respondents (89.7%) have at least one insurance, 473 respondents (88.7%) have no comorbidities, and 426 respondents' family members (78.3%) have no comorbidities. The number of respondents that smoke or had a history of mental disorders is very low, with 24 respondents (4.6%) and eight respondents (1.5%), respectively.

Although the majority (75.3%) claim that no known close contacts are positive for COVID-19 and most respondents (92.5%) never experienced COVID-19 symptoms, 238 respondents (45.6%) have done at least one COVID-19 test. Respondents are mostly independent (60.7%) for registering their vaccination schedule, while 300 respondents (57.5%) do not obtain permission for vaccination. Regarding vaccination stance, 443 respondents (84.9%) are “vaccine acceptance.” Amongst the “vaccine hesitance and refusal” group, the majority is male respondents with 44 respondents (55.7%), married (64 respondents; 81%), non-Chinese (60 respondents; 75.9%), working (61 respondents; 77.2%), lives with another family member (74 respondents; 93.7%), and lives with children or grandchildren (52 respondents; 65.8%) (results not shown).

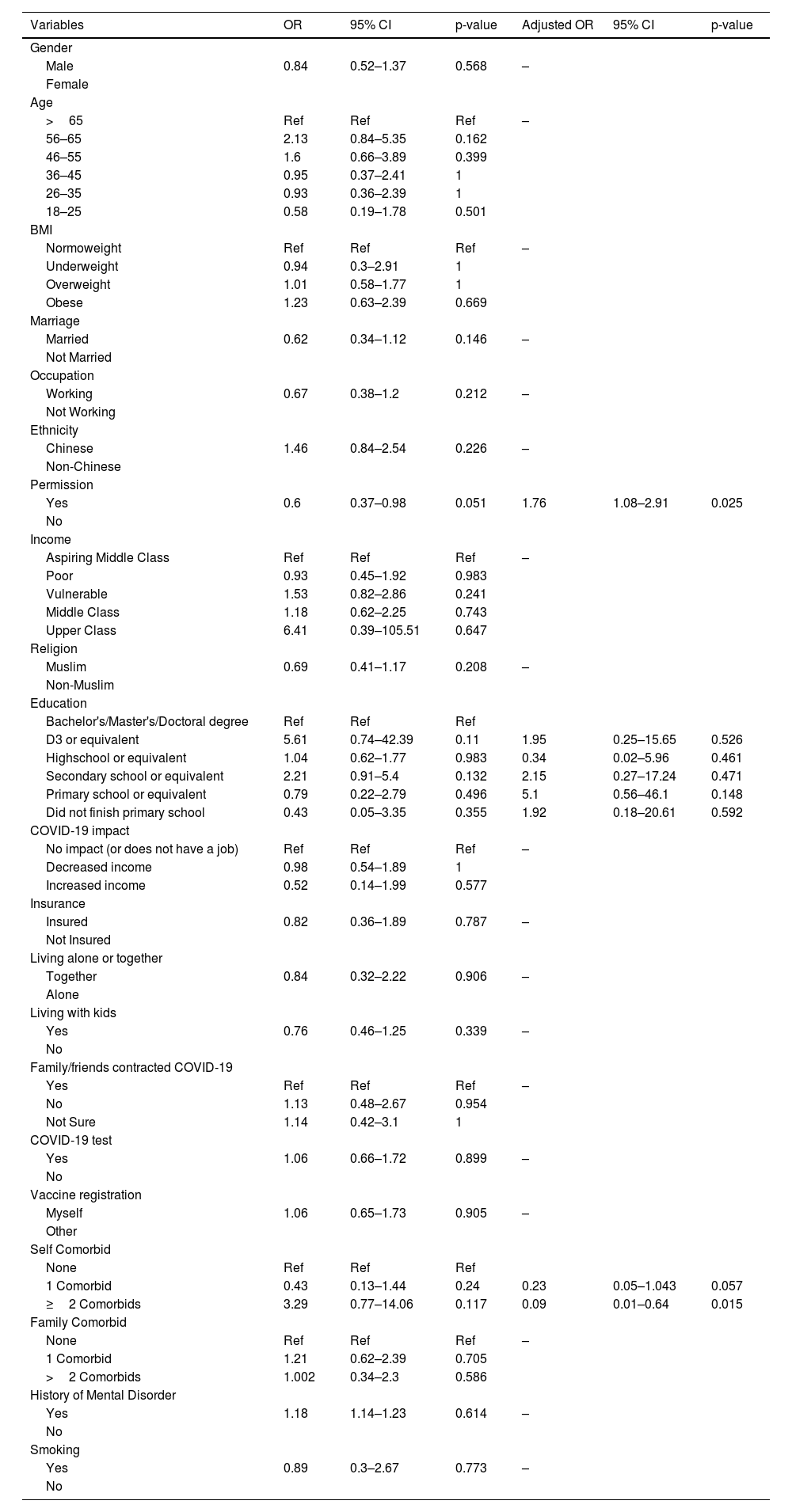

Multivariate analysis reveals that respondents who obtain permission from work or school to get vaccinated are more likely to be “vaccine acceptance” with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.76 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–2.91; p-value 0.025), and respondents with two or more comorbidities are less likely to be “vaccine acceptance” with an OR of 0.09 (95% CI 0.01–0.64; p-value 0.015) (Table 2). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test yields a p-value of 0.99 while the AUC is 0.646 (95% CI 0.581–0.711; p-value <0.0001) (Fig. 2). These results indicate that this model has low discrimination with good calibration.

Bivariate and Multivariate analysis of variables.

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 0.84 | 0.52–1.37 | 0.568 | – | ||

| Female | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| >65 | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| 56–65 | 2.13 | 0.84–5.35 | 0.162 | |||

| 46–55 | 1.6 | 0.66–3.89 | 0.399 | |||

| 36–45 | 0.95 | 0.37–2.41 | 1 | |||

| 26–35 | 0.93 | 0.36–2.39 | 1 | |||

| 18–25 | 0.58 | 0.19–1.78 | 0.501 | |||

| BMI | ||||||

| Normoweight | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| Underweight | 0.94 | 0.3–2.91 | 1 | |||

| Overweight | 1.01 | 0.58–1.77 | 1 | |||

| Obese | 1.23 | 0.63–2.39 | 0.669 | |||

| Marriage | ||||||

| Married | 0.62 | 0.34–1.12 | 0.146 | – | ||

| Not Married | ||||||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Working | 0.67 | 0.38–1.2 | 0.212 | – | ||

| Not Working | ||||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Chinese | 1.46 | 0.84–2.54 | 0.226 | – | ||

| Non-Chinese | ||||||

| Permission | ||||||

| Yes | 0.6 | 0.37–0.98 | 0.051 | 1.76 | 1.08–2.91 | 0.025 |

| No | ||||||

| Income | ||||||

| Aspiring Middle Class | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| Poor | 0.93 | 0.45–1.92 | 0.983 | |||

| Vulnerable | 1.53 | 0.82–2.86 | 0.241 | |||

| Middle Class | 1.18 | 0.62–2.25 | 0.743 | |||

| Upper Class | 6.41 | 0.39–105.51 | 0.647 | |||

| Religion | ||||||

| Muslim | 0.69 | 0.41–1.17 | 0.208 | – | ||

| Non-Muslim | ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| Bachelor's/Master's/Doctoral degree | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| D3 or equivalent | 5.61 | 0.74–42.39 | 0.11 | 1.95 | 0.25–15.65 | 0.526 |

| Highschool or equivalent | 1.04 | 0.62–1.77 | 0.983 | 0.34 | 0.02–5.96 | 0.461 |

| Secondary school or equivalent | 2.21 | 0.91–5.4 | 0.132 | 2.15 | 0.27–17.24 | 0.471 |

| Primary school or equivalent | 0.79 | 0.22–2.79 | 0.496 | 5.1 | 0.56–46.1 | 0.148 |

| Did not finish primary school | 0.43 | 0.05–3.35 | 0.355 | 1.92 | 0.18–20.61 | 0.592 |

| COVID-19 impact | ||||||

| No impact (or does not have a job) | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| Decreased income | 0.98 | 0.54–1.89 | 1 | |||

| Increased income | 0.52 | 0.14–1.99 | 0.577 | |||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Insured | 0.82 | 0.36–1.89 | 0.787 | – | ||

| Not Insured | ||||||

| Living alone or together | ||||||

| Together | 0.84 | 0.32–2.22 | 0.906 | – | ||

| Alone | ||||||

| Living with kids | ||||||

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.46–1.25 | 0.339 | – | ||

| No | ||||||

| Family/friends contracted COVID-19 | ||||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| No | 1.13 | 0.48–2.67 | 0.954 | |||

| Not Sure | 1.14 | 0.42–3.1 | 1 | |||

| COVID-19 test | ||||||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.66–1.72 | 0.899 | – | ||

| No | ||||||

| Vaccine registration | ||||||

| Myself | 1.06 | 0.65–1.73 | 0.905 | – | ||

| Other | ||||||

| Self Comorbid | ||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| 1 Comorbid | 0.43 | 0.13–1.44 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.05–1.043 | 0.057 |

| ≥2 Comorbids | 3.29 | 0.77–14.06 | 0.117 | 0.09 | 0.01–0.64 | 0.015 |

| Family Comorbid | ||||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | – | ||

| 1 Comorbid | 1.21 | 0.62–2.39 | 0.705 | |||

| >2 Comorbids | 1.002 | 0.34–2.3 | 0.586 | |||

| History of Mental Disorder | ||||||

| Yes | 1.18 | 1.14–1.23 | 0.614 | – | ||

| No | ||||||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 0.89 | 0.3–2.67 | 0.773 | – | ||

| No | ||||||

Our results indicate that 84.9% of our respondents accept the vaccine. This number is way higher than the previous finding, 65% out of 112,888 respondents, both in Indonesia and Jambi city.18 One reason that can explain this disparity is that respondents are asked about vaccination stance in the vaccination center, making it more likely that respondents have already accepted vaccination.27

From the multivariate analysis, permission to get vaccinated and presence of ≥2 comorbidities are the only significant variables that affect respondents to be “vaccine acceptance”. The reason behind obtaining permission is due to the convenience. People prioritise income even more in the pandemic where unemployment and wage cuts are prevalent.28 When the study is conducted, vaccines are not mandatory yet. Therefore, obtaining a leave to be vaccinated may be inconvenient as workers might deal with supervisors who are not understanding enough. This finding is also supported by other studies where inconvenience in getting the vaccine is associated with lower uptake.14,29 Initially, in the bivariate analysis, getting a permit is not significantly associated with vaccine stance. Confoundings such as occupation, income and the impact of COVID-19 on income may play a role as collider bias.30

The first COVID-19 vaccine to be approved at that time still leaves a lot of questions unanswered, such as the safety issues amongst people with comorbidities. This leaves organisations to recommend against vaccinating a certain group of people with specific comorbidities until further evidence is obtained.22,31 It is also known that patients with comorbidities are more likely to die from COVID-19 related complications.32 Therefore, it is natural for patients with comorbidities to decide against being vaccinated.33,34 Reasons that may explain this phenomenon include fear of the vaccination side-effects amongst people with comorbidities, poor knowledge about the vaccines, and misinformation regarding COVID-19 vaccines. This finding has also been found in other countries.35–38

Increasing age,38–41 male sex,39,41,42 having health insurance,38,43 knowing others contract COVID-19,41,43 higher income,44 higher level of education,39 ethnicities,38,39 a large household size,41 smokers,45,46 and mental well-being41 are some of the factors that are significantly associated with vaccine acceptance in other studies but not in ours. Several reasons may explain these phenomena. Firstly, our study was done during phase two of the national vaccination scheme, where the target populations are public service workers and the elderly.21 This eliminates the effects of jobs and income towards vaccination stance as it is made mandatory for public service workers to get a vaccination jab by the government. One study finds that instructions from supervisors or the head of the institutions predict vaccine acceptance strongly.40 This might downplay the impacts of age and sex, and the population studied need to be vaccinated per government mandate. The second reason is because vaccinations are given for free in every Puskesmas. Therefore, having a medical insurance and income might not affect vaccine acceptance.47 As for the history of mental health, one study in China finds that vaccine acceptance amongst people with and without mental disorders are similar. The difference lies in their willingness to pay for the vaccine.48 Lastly, the effects of living with other family members or smoking on vaccine acceptance may be mediated by people with ≥2 comorbidities. People are more willing to be vaccinated so that they can protect themselves and their loved ones.14

Our studies suffer from several limitations. Firstly, vaccination policies change according to the COVID-19 situation in Indonesia and rapid advancement in the knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine. During the timeframe of our study, vaccination for pregnant women and children is not yet made available; thus, the vaccine acceptance might be falsely high in our study.49–51 Secondly, the study is conducted in a single-center where respondents are vaccinated. Therefore, it falsely elevates the vaccine acceptance rate compared to surveying the general population online.18 The third limitation is that our study has a poor discriminant. This finding suggests that other predictive variables not explored in our study may affect vaccine acceptance. Lastly, our study only achieves a 37.3% (522/1400) response rate, introducing a non-response bias.52

Despite some limitations, our study has some merits as well. Amongst other studies that look into vaccine acceptance in Indonesia,53–56 our study is one of the few studies conducted in person. Therefore, our study does not suffer from the limitations introduced by web-based surveys, such as sampling issues and responder bias.57,58 The other strength of this study is a high vaccination acceptance rate. This may guide the government to tailor their policies, such as allowing permit leave to be vaccinated and launching an awareness campaign for people with comorbidities to feel safe to get a jab. Lastly, our study ends before COVID-19 is made compulsory for anyone. Failure to be vaccinated results in not travelling, going to public spaces, or even working.59 Conducting a study might introduce a bias in the vaccination stance as vaccines are made the prerequisite to allow people to do their regular activities normally.

ConclusionThere is a high vaccine acceptance in this study. Difficulties in getting a work permit and the presence of ≥2 comorbidities decrease the willingness to be vaccinated for COVID-19. The government, therefore, needs to play a role in ensuring that companies or workplaces do not punish employees for taking a leave to be vaccinated. A collaboration with healthcare workers is also needed to educate Indonesians that the vaccine is safe for people with comorbidities as long as no contraindications are present. In this manner, the vaccine acceptance rate may be increased, especially when the booster jab is implemented soon.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe Faculty of Medicine Universitas Pelita Harapan granted this study's ethical permission with an approval number of 155/K-LKJ/ETIK/VI/2021.

Availability of data and materialsAvailable upon request.

FundingThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any financial grants.

Authors' contributionsGSO, HEP, and TAY did the conception of this research. Data collections and cleaning are done by GSO, HN, and CI. Statistical analysis were done by GSO and RSH. GSO, RSH, HN, and CI drafted the article while TAY and HEP did critical revision of the article. Final approval of the version to be published was granted by all authors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

We would want to express our gratitude to the vaccination team of Puskesmas Putri Ayu for doing such a good gesture and assisting us with our research. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any financial grants.