Editado por: Dra. Núria Torner CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Publica CIBERESP Unitat de Medicina Preventiva i Salut Pública Departament de Medicina, Universitat de Barcelona

Más datosDespite the fact that the WHO recommends that adults over the age of 18 have to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. The willingness and intention to accept a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine remain major issues among the general population, particularly patients with comorbid disease conditions. The aim of this study was to assess the patterns regarding COVID-19 infection and vaccination, along with the intention and hesitancy to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with comorbid disease conditions in Istanbul, Türkiye.

MethodsThis was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted among patients with comorbid disease conditions using a three-part, structured, validated questionnaire. Vaccine hesitancy from a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine was assessed using the Health Belief Model (HBM), based on a 5-point Likert-type scale.

ResultsThe study enrolled 162 participants with a mean age of 57.2 ± 13.3 years. 97% of the respondents received the COVID-19 vaccine. Almost half of respondents (51.2%) reported receiving information about a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. HBM among the participants with comorbidities showed a significant agreement regarding the perceived susceptibility (P < 0.0001), perceived severity (P < 0.0001) and perceived benefits (P < 0.0001) to receive a booster vaccine dose. There was a statistically significant correlation between the intention to receive a booster vaccine dose and education level (university education; P < 0.0001).

ConclusionA vast and significant majority of patients with chronic comorbid disease conditions who received the COVID-19 vaccine reported an intention to receive a booster dose.

A pesar de que la OMS recomienda que los adultos mayores de 18 años reciban una dosis de refuerzo de la vacuna contra el COVID-19. La voluntad y la intención de aceptar una dosis de refuerzo de la vacuna COVID-19 siguen siendo problemas importantes entre la población general, en particular los pacientes con enfermedades comórbidas. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar los patrones con respecto a la infección y vacunación de COVID-19, junto con la intención y la indecisión de recibir una dosis de refuerzo de la vacuna COVID-19 entre pacientes con enfermedades comórbidas en Estambul, Turquía.

MétodosEste fue un estudio descriptivo transversal realizado entre pacientes con enfermedades comórbidas utilizando un cuestionario validado, estructurado y de tres partes. La vacilación de la vacuna de una dosis de refuerzo de la vacuna COVID-19 se evaluó utilizando el Modelo de creencias de salud (HBM), basado en una escala tipo Likert de 5 puntos.

ResultadosEl estudio inscribió a 162 participantes con una edad media de 57,2 ± 13,3 años. El 97% de los encuestados recibió la vacuna COVID-19. Casi la mitad de los encuestados (51,2%) informaron haber recibido información sobre una dosis de refuerzo de la vacuna contra la COVID-19. HBM entre los participantes con comorbilidades mostró un acuerdo significativo con respecto a la susceptibilidad percibida (P < 0,0001), la gravedad percibida (P < 0,0001) y los beneficios percibidos (P < 0,0001) para recibir una dosis de vacuna de refuerzo. Hubo una correlación estadísticamente significativa entre la intención de recibir una dosis de vacuna de refuerzo y el nivel educativo (educación universitaria; P < 0,0001).

ConclusiónUna gran y significativa mayoría de los pacientes con enfermedades comórbidas crónicas que recibieron la vacuna contra el COVID-19 informaron tener la intención de recibir dosis de refuerzo.

Since the first case of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 disease) was reported in December 2019, the exponential growth of the pandemic has profoundly changed all aspects of people's lives. Due to the significant and unprecedented public health impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic and associated morbidity and mortality, several preventive measures, such as daily activity restriction, social isolation for several months, and vaccination, are being implemented to strictly control the pandemic.1,2 Comorbidities are associated with poorer health outcomes, more complex clinical care, and increased health care costs.3 Due to their low immune status, the clinical outcomes and length of hospital stay are directly related to the comorbidities and age of COVID-19 patients. Previous studies on the prevalence of clinical features and comorbidities in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 reported that diabetes mellitus, obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), and chronic respiratory disease were significant risk factors associated with disease severity, hospitalisation, and a high mortality rate compared to patients without comorbidities.4–6 A study in China conducted by Wang et al.7 reported that patients with comorbid disease conditions, including hypertension, had a median survival of 25 days. Likewise, the severity of the COVID-19 disease becomes threefold in patients with diabetes mellitus.8 A study in the UK found that 18.3% of hospitalised COVID-19 patients developed type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) and 26% of those with diabetes died.9

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has approved several vaccines against the COVID-19 virus. These vaccines will not be able to fight the epidemic unless they are widely accepted by the community to achieve at least 75% levels of immunity to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccination is therefore one of the most important ways to protect against the serious complications of COVID-19.10,11 The benefits of vaccination outweigh the risks given that patients with comorbidities are at increased risk of severe illness or death when infected with COVID-19.

Therefore, the COVID-19 vaccine guidelines issued by the Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP), the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), and the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation (SAGE) recommend COVID-19 vaccination for patients with comorbidities.12–14

Meanwhile, two years have passed since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it appears that it is far from over, as waves of SARS-CoV2 infections continue to be identified as different variants emerge around the world. Protection provided by two-dose schedules of various COVID-19 vaccines is slowly waning against serious infections, hospitalizations, and mortality.15 Previous studies have shown that adults who received a third or repeat dose of any mRNA-based vaccine had a significantly lower risk of re-infection with COVID-19 or even mild symptoms of the disease, even if they were infected, compared to those who weren't vaccinated or received only two doses.16,17 A booster dose is a second dose of a vaccine given after a primary vaccination series has been completed.6 Current studies indicate that protective immunity wanes between four and six months after the primary COVID-19 vaccination. In healthy adults, it has been demonstrated that receiving a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, particularly of any mRNA-based vaccination, improves peak antibody levels and significantly increases immunogenicity, lower risk of re-infection or with mild symptoms of the disease, even if infected, compared to those who were unvaccinated or received only two doses. Furthermore, as the arrival of new variants, and a decrease in long-term protection, the WHO recommends that adults over the age of 18 receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine four to six months after completing the primary vaccination series.18–23

However, acceptance and willingness to accept a booster COVID-19 vaccine or immunisation programme is a major concern among the population, especially given the rapid use of new and marketed vaccines and concerns about vaccine safety in short-term trials and vaccination programmes.24,25 Vaccine hesitancy is defined as a set of beliefs, attitudes, behaviours, or a combination of these that manifest as a delay in accepting or refusing vaccines.26,27 It is therefore important to increase public confidence in vaccination. Little is known about the intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, attitudes toward receiving a booster dose, and associated factors in patients with comorbid conditions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the patterns regarding COVID-19 infection and vaccination along with the intention, and hesitancy to receive a boost dose of COVID-19 vaccine among patients with comorbid disease conditions in Istanbul, Türkiye.

MethodsStudy setting and participantsThis was a descriptive, cross-sectional study that enrolled a convenient sample size of patients with comorbid disease conditions in Istanbul, Türkiye, from March to August 2022. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Istinye University, Istanbul, Türkiye (ref. number: 2022-22-46). To ensure generalizability and minimise selection bias, a three-stage sampling method based on population density (high, medium, and low) was achieved during the study. Five community pharmacies were conveniently selected from each of the three clusters, for a total of 15 pharmacies. A sample size of a large population with an unknown degree of variability is a 95% confidence level with 5% precision, assuming maximum variability. A total of 292 participants were contacted during this study. However, 162 participants completed the entire questionnaire.

Inclusion criteria included patients older than 18 years with a diagnosis of chronic disease conditions or comorbidities who visited any study site during the study period, including those who received full doses of COVID-19 vaccines launched by the Turkish Ministry of Health. Those with no chronic disease conditions, those who dismissed participation, or those with incomplete responses to the items of the questionnaire were excluded from the study. Data collection instruments were administered to eligible patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study, which lasted approximately 10 min. All participants in the study were informed about the purpose and description of the study, they were given an informed consent form and the opportunity to give their consent. In addition, they were also informed that their participation was voluntary and were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses prior to participation.

Questionnaire developmentThe information was collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire that was developed for the present study. The objectives of the study were described in an introductory letter included with the questionnaire, which was distributed and filled out by the participants and took nearly 10 min to complete. The questionnaire was developed after a thorough and comprehensive literature review and was adapted to meet the purpose of this study by reformatting. The questionnaires were translated back and forth from English to Turkish, and the content was confirmed by two pharmacists and medical staff. In addition, a pre-test of the study was administered to approximately 5% of the target sample to rule out ambiguities in question items and determine whether the data provided reliable information. The data collected during this pilot were excluded from the statistical analysis of the final data.

The final version of the questionnaire consisted of 28 questions divided into four parts. The first section consisted of seven items and collected information on the demographic characteristics of the participants, including age, gender, educational level, smoking status, types, and duration of chronic disease conditions in years, and number of drugs used for treatment of chronic disease conditions. The second part consisted of five items that assessed patients' patterns and experiences of COVID-19 infection. The third part consisted of eight items that assessed patients' habits and perceptions about the COVID-19 vaccination, and respondents could answer “yes” or “no”. The fourth part assessed the impact of vaccine hesitancy on the COVID-19 vaccine using the Health Belief Model (HBM),26 a theoretical framework representing five domains and consisting of 14 items. A key premise of HBM is that existing beliefs can predict future behaviours, such as receiving a booster dose of a vaccine. Therefore, the application of HBM in disease prevention can explain the motivation of people who want to vaccinate and the reasons for refusing to vaccinate. Domains of the HBM included perceived susceptibility, which consists of two parts that relate to an individual's belief about the likelihood of contracting a disease; perceived severity, which consists of three components, refers to an individual's feelings about the severity of such an illness; perceived benefit, which consists of three components related to an individual's perception of the usefulness of a particular health behaviour; perceived barriers, which consists of three parts related to the assessment of barriers that can prevent an individual from performing the health behaviour in question, and action cues, which consists of two parts, refers to cues that stimulate certain behaviours.

The respondents were given response options on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; = agree; 5 = strongly agree). The total score for each domain was the sum of all item scores in the domain. The scale was slightly modified into a 3-point rating of strong beliefs, poor beliefs, and neutral beliefs (neither strong nor bad) to ease the running of the statistical analysis.

Statistical analysisData were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 23.0 and Microsoft Office Excel 2013. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the study population, and the results were expressed in numbers, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The Chi-square test was used to assess the intention and hesitancy toward accepting COVID-19 vaccines among the study participants. The P-value was considered significant at <0.05 and highly significant at <0.01.

ResultsTable 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants with a mean age of 57.2 ± 13.3 years, and most of the respondents were in the age range of 51–60 years (32.1%), followed by 61–70 years (23.5%). Almost half of the study participants were females (54.3%). Most of the enrolled participants possessed a university level qualification (43.2%). Most of the participants were non-smokers (73.5%). Cardiovascular diseases were the most common chronic conditions encountered among the study participants (98%), followed by endocrine diseases (69%) particularly type 2 DM (24%). The mean duration of disease conditions was 11.5 ± 8.21 years, and 40.1% had chronic disease conditions lasting more than 10 years. A total of 453 medicines, with a mean of 2.8 ± 2 per patient, were recorded in the present study. Patients receiving ≥4 medicines simultaneously (polypharmacy) were reported in 23.5% of the study participants. Fig. 1 shows participants' patterns of infection with COVID-19, 40.7% reported history of infection with COVID-19, and 19.7% reported hospital admission from COVID-19 infection.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants (N = 162).

| Variables | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years± SD) | 57.2 ± 13.3 | – |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 74 | 45.7 |

| Female | 88 | 54.3 |

| Age range (years) | ||

| 30–40 | 14 | 8.6 |

| 41–50 | 33 | 20.4 |

| 51–60 | 52 | 32.1 |

| 61–70 | 38 | 23.5 |

| >70 | 25 | 15.4 |

| Educational level | ||

| No education | 5 | 3.1 |

| Primary | 38 | 23.5 |

| Secondary | 49 | 30.2 |

| University | 70 | 43.2 |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Yes | 43 | 26.5 |

| No | 119 | 73.5 |

| ⁎Chronic medical condition (n = 198) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 98 | 49.5 |

| Endocrine | 69 | 34.8 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | 2.0 |

| Renal | 3 | 1.5 |

| Respiratory | 14 | 7.1 |

| Others | 10 | 5.1 |

| Duration of disease condition (years) | 11.5 ± 8.21 | |

| 1–5 | 49 | 30.2 |

| 6–10 | 48 | 29.6 |

| >10 | 65 | 40.1 |

| Number of medicines intake | 453 | |

| Mean umber of medicines intake per patient (± SD) | 2.8 ± 2.0 |

Data presented as number (n) and percentage (%).

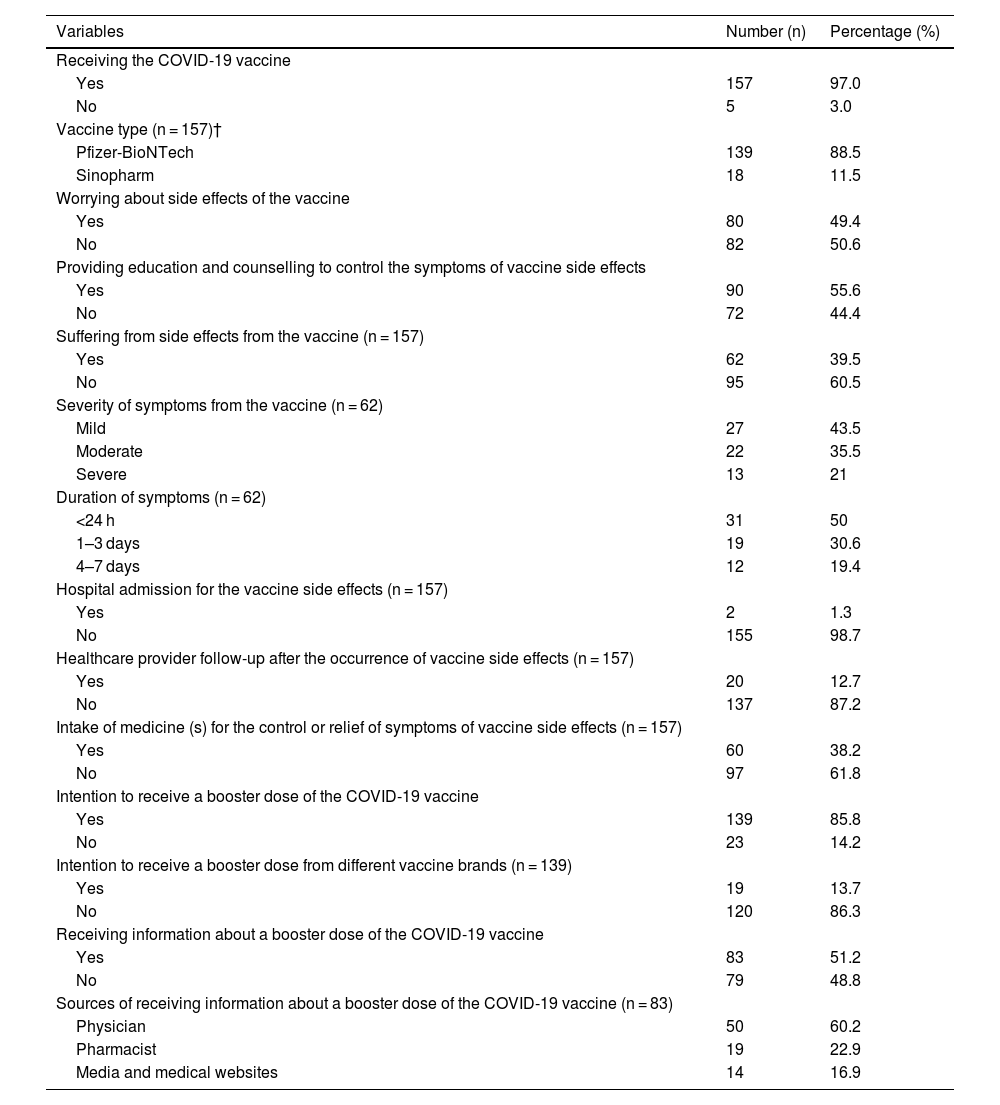

Table 2 shows the patterns regarding the COVID-19 vaccination among the study participants with 97% received the COVID-19 vaccine. Of these, 88.5% (n = 139) received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. 49.4% of the respondents were concerned about the appearance of vaccine side effects. More than half of the participants (55.6%) received education and counselling to manage symptoms of vaccine side effects. Meanwhile, 39.5% (n = 62) of the participants suffered from side effects of the vaccine they received. Of these, 43.5% (n = 27) reported mild symptoms of COVID-19 infection, followed by moderate symptoms (35.5%, n = 22). Half of them reported COVID-19 symptoms which was lasting less than 24 (n = 31, 50%). On the other hand, 12.7% of participants reported being followed up by a health care provider after reporting a vaccine side effect, and 38.2% reported taking medication to relieve symptoms of a vaccine side effect. Regarding perceptions of receiving a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 85.8% of the participants reported an intention to receive the booster dose. Of these, 86.3% reported an intention to receive the booster dose from the same vaccine brand. Almost half of respondents (51.2%) reported receiving information about a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and a physician was the primary source of information (60.2%), as shown in Table 2.

Patterns regarding the COVID-19 vaccination among the study participants (N = 162).

| Variables | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Receiving the COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| Yes | 157 | 97.0 |

| No | 5 | 3.0 |

| Vaccine type (n = 157)† | ||

| Pfizer-BioNTech | 139 | 88.5 |

| Sinopharm | 18 | 11.5 |

| Worrying about side effects of the vaccine | ||

| Yes | 80 | 49.4 |

| No | 82 | 50.6 |

| Providing education and counselling to control the symptoms of vaccine side effects | ||

| Yes | 90 | 55.6 |

| No | 72 | 44.4 |

| Suffering from side effects from the vaccine (n = 157) | ||

| Yes | 62 | 39.5 |

| No | 95 | 60.5 |

| Severity of symptoms from the vaccine (n = 62) | ||

| Mild | 27 | 43.5 |

| Moderate | 22 | 35.5 |

| Severe | 13 | 21 |

| Duration of symptoms (n = 62) | ||

| <24 h | 31 | 50 |

| 1–3 days | 19 | 30.6 |

| 4–7 days | 12 | 19.4 |

| Hospital admission for the vaccine side effects (n = 157) | ||

| Yes | 2 | 1.3 |

| No | 155 | 98.7 |

| Healthcare provider follow-up after the occurrence of vaccine side effects (n = 157) | ||

| Yes | 20 | 12.7 |

| No | 137 | 87.2 |

| Intake of medicine (s) for the control or relief of symptoms of vaccine side effects (n = 157) | ||

| Yes | 60 | 38.2 |

| No | 97 | 61.8 |

| Intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| Yes | 139 | 85.8 |

| No | 23 | 14.2 |

| Intention to receive a booster dose from different vaccine brands (n = 139) | ||

| Yes | 19 | 13.7 |

| No | 120 | 86.3 |

| Receiving information about a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| Yes | 83 | 51.2 |

| No | 79 | 48.8 |

| Sources of receiving information about a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine (n = 83) | ||

| Physician | 50 | 60.2 |

| Pharmacist | 19 | 22.9 |

| Media and medical websites | 14 | 16.9 |

Data presented as number (n) and percentage (%).

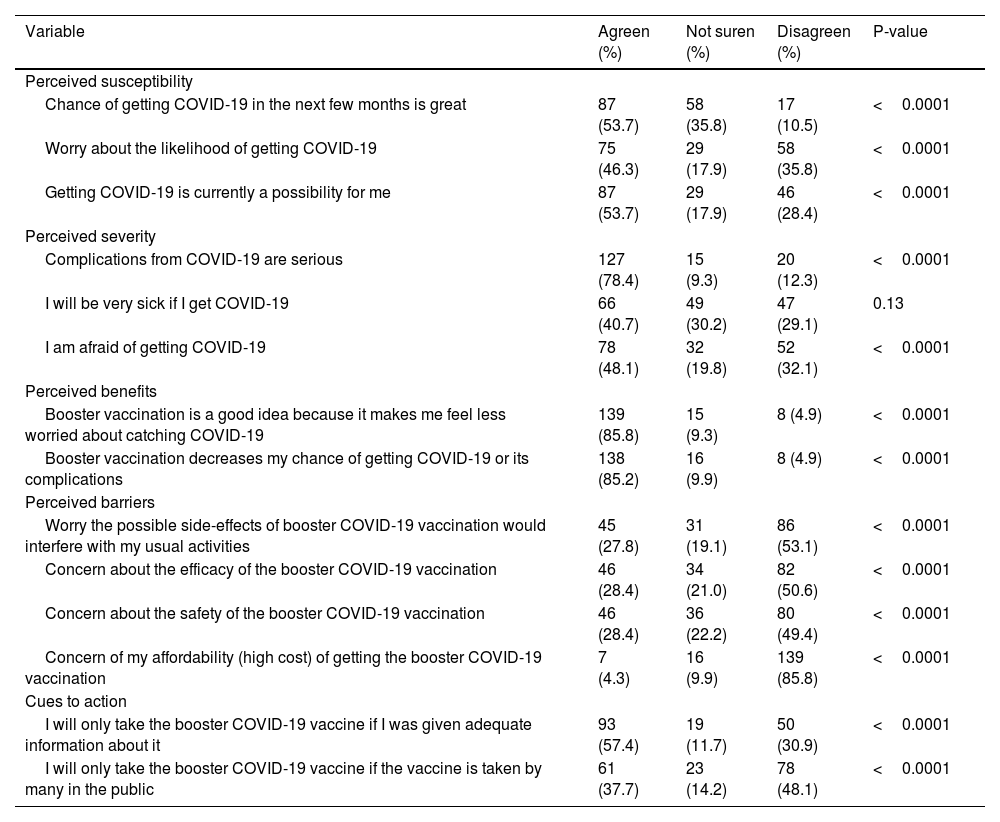

The intention and willingness to receive a booster COVID-19 vaccine based on the HBM among the study participants are shown in Table 3. Regarding the perceived susceptibility, nearly half of the participants reported a significant agreement that there was a great chance of getting COVID-19 in the next few months (53.7%, P < 0.0001), were also worried about the likelihood of getting COVID-19 (46.3%, P < 0.0001), and that it was currently possible that they would get COVID-19 (53.7%, P < 0.0001). The participants rated the seriousness of COVID-19 complications as high (78.4%, P < 0.0001) and were afraid of getting COVID-19 (48.1%, P < 0.0001). Nonetheless, nearly an equal proportion of participants (85%) reported significant agreement about the benefits of booster COVID-19 vaccination and perceived the benefit of feeling less worried about contracting the coronavirus after receiving the booster COVID-19 vaccine, as well as reducing the risk of infection and associated complications (P < 0.0001). Regarding the perceived barriers, nearly half of the respondents reported disagreement about the concerns of the safety and efficacy of the booster COVID-19 vaccine (P < 0.0001). Moreover, most of the participants also reported disagreement about the concern for the affordability (high cost) of the booster COVID-19 vaccine (85.85, P < 0.0001). Similarly, many of the participants reported that they would receive the booster COVID-19 vaccine if given adequate information (57.4%, P < 0.0001), and they would not take the booster vaccine if many others in the public did (48.1%, P < 0.0001).

Intention and willingness to receive a booster COVID-19 vaccine based on the HBM among the study participants (N = 162).

| Variable | Agreen (%) | Not suren (%) | Disagreen (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | ||||

| Chance of getting COVID-19 in the next few months is great | 87 (53.7) | 58 (35.8) | 17 (10.5) | <0.0001 |

| Worry about the likelihood of getting COVID-19 | 75 (46.3) | 29 (17.9) | 58 (35.8) | <0.0001 |

| Getting COVID-19 is currently a possibility for me | 87 (53.7) | 29 (17.9) | 46 (28.4) | <0.0001 |

| Perceived severity | ||||

| Complications from COVID-19 are serious | 127 (78.4) | 15 (9.3) | 20 (12.3) | <0.0001 |

| I will be very sick if I get COVID-19 | 66 (40.7) | 49 (30.2) | 47 (29.1) | 0.13 |

| I am afraid of getting COVID-19 | 78 (48.1) | 32 (19.8) | 52 (32.1) | <0.0001 |

| Perceived benefits | ||||

| Booster vaccination is a good idea because it makes me feel less worried about catching COVID-19 | 139 (85.8) | 15 (9.3) | 8 (4.9) | <0.0001 |

| Booster vaccination decreases my chance of getting COVID-19 or its complications | 138 (85.2) | 16 (9.9) | 8 (4.9) | <0.0001 |

| Perceived barriers | ||||

| Worry the possible side-effects of booster COVID-19 vaccination would interfere with my usual activities | 45 (27.8) | 31 (19.1) | 86 (53.1) | <0.0001 |

| Concern about the efficacy of the booster COVID-19 vaccination | 46 (28.4) | 34 (21.0) | 82 (50.6) | <0.0001 |

| Concern about the safety of the booster COVID-19 vaccination | 46 (28.4) | 36 (22.2) | 80 (49.4) | <0.0001 |

| Concern of my affordability (high cost) of getting the booster COVID-19 vaccination | 7 (4.3) | 16 (9.9) | 139 (85.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cues to action | ||||

| I will only take the booster COVID-19 vaccine if I was given adequate information about it | 93 (57.4) | 19 (11.7) | 50 (30.9) | <0.0001 |

| I will only take the booster COVID-19 vaccine if the vaccine is taken by many in the public | 61 (37.7) | 23 (14.2) | 78 (48.1) | <0.0001 |

Data presented as number (n) and percentage (%).

Significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Stratifying the demographic characteristics and the intention to receive a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants is shown in Table 4. The findings of the present study showed that there was a statistically significant finding between the intention to receive a booster vaccine dose and education level (university education; P < 0.0001). Similarly, there was a statistically significant between receiving information about a booster vaccine dose and education level (university education; P < 0.0001), as well as disease duration of more than 10 years (P = 0.005).

Correlation between demographic characteristics with the intention to receive booster COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants.

| Variable | Intention to receive a booster vaccine dose (n=139) | P-value | Intention to receive a booster vaccine dose from different vaccine brands (n=19) | P-value | Receiving information about a booster vaccine dose (n=83) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Males | 68 (49) | 0.85 | 10 (52.6) | 0.81 | 36 (43.4) | 0.22 |

| Females | 71 (51) | 9 (47.4) | 47 (56.6) | |||

| Educational level | ||||||

| No education | 3 (2.2) | 1 (5.2) | 2 (2.4) | <0.0001 | ||

| Primary | 27 (19.4) | <0.0001 | 5 (26.3) | 0.22 | 18 (21.7) | |

| Secondary | 45 (32.4) | 6 (31.7) | 25 (30.1) | |||

| University | 64 (46) | 7 (36.8) | 38 (45.8) | |||

| Duration of disease condition (years) | ||||||

| 01-May | 42 (30.2) | 4 (21.1) | 25 (30.1) | |||

| 06-Oct | 44 (31.7) | 0.4 | 10 (52.6) | 0.19 | 17 (20.5) | 0.005 |

| >10 | 53 (38.1) | 5 (26.3) | 41 (49.4) |

Data presented as number (n) and percentage (%).

Significant at P ≤ 0.05.

High acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines and achieving very high vaccination coverage, including booster doses, represents the most important public health strategy to control the pandemic, especially among population with comorbid disease conditions for which high transmission rates have been recorded. Therefore, efforts are still needed to address hesitancy to receive a booster dose, particularly among those who expressed definite and partial unwillingness and those who remain undecided. Employing the HBM has revealed useful data about the influence of the various domains on the acceptance of the booster vaccine among patients with comorbid disease conditions. In the current study, the perceived benefits of the booster vaccine were noted, as most of the participants who were already vaccinated were willing to receive a booster dose vaccination. They also felt that the booster vaccine would be effective, protect them from getting the infection. A possible explanation relates to the timing of the current study being more recent than previous COVID-19 vaccine studies and the estimated higher proportion of patients receiving boosters.

The acceptance rate, belief in the vaccine benefit to prevent infections and subsequent complications, perceived susceptibility for contracting the infection and perceived severity of COVID-19 were appreciated in our study sample. These results were comparable to the previous studies among different populations conducted in China (91.1%)28, Denmark (90%),29 and higher than the willingness rate to accept a booster dose of COVID-19 in studies conducted in Chile (88.2%),30 Malaysia (82.2%),31 Poland (71%),32 the USA (58.5%),33 and Jordan (44.6%).34 Furthermore, our findings were consistent with a study conducted by Rzymski et al.,32 which reported that willingness to receive a booster dose was significantly higher in older subjects and those with chronic diseases who are vulnerable to morbidity and mortality. However, the findings of our study were in contrast with those conducted in Malaysia, which reported that having chronic diseases was not significantly associated with COVID-19 vaccine booster acceptance.31

Effective and safe vaccines are considered critical among patients with comorbid disease conditions in combating the COVID-19 pandemic to achieve population immunity. Despite accumulating evidence supporting the safety and effectiveness of the currently approved COVID-19 vaccines, safety, efficacy, and potential side effects remain the key concerns with the COVID-19 vaccines.35 Most of the study respondents reported a mild incidence of side effects from COVID-19 vaccines. However, most of them disagreed that the occurrence of side effects would preclude them from getting a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. These results were in contrast to those in a study that investigated the acceptance of the booster COVID-19 dose in countries in the Mediterranean region. The study showed that hesitancy to receive a booster dose was associated with worries about the safety and efficacy of current vaccines.36 In the present study, most of the participants received the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. They preferred a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine that necessarily matches the vaccine used previously, likely due to safety concerns. The degree of relevant side effects following the first or second dosage was typically correlated with preference for the same vaccine, highlighting the importance of earlier experiences in vaccine perception and trust. Our results are in line with those of a prior study carried out among the Polish population, which found that most participants who had previously received mRNA vaccinations preferred to receive the same vaccination.33

Almost half of respondents reported receiving information about a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and a physician was the primary source of information for this group. Sources unaffiliated with official health authorities provide exaggerated, inaccurate, and misleading information that can adversely affect public mental health, causing fear and anxiety in critical group of patients (those with comorbidities). This fear, in turn, could adversely affect the willingness to receive a potentially effective and safe COVID-19 vaccine that may bring the pandemic to an end. People should therefore be advised to follow and contact their local health authorities for the most relevant information.37

In the current study, there were noticeable demographic disparities in willingness and acceptance to receive a booster dose, which were significantly higher in those with a high education level (university education) and disease duration of more than ten years. However, the present study showed that gender was not significantly associated with willingness to receive a booster dose. These findings are in accordance with a study conducted by Weitzer et al38 Similarly, Savoia et al.,39 also reported that respondents with high education had a lower level of hesitancy compared to those with lower education degrees (OR = 0.66, 95% C.I. 0.44–0.99). In contrast to our study, Rzymski et al.32 and Savoia et al.39 reported that willingness to receive a booster dose was significantly higher among women.

Considering the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants with immune escape potential, besides the waning of population immunity. Booster doses of COVID-19 vaccine are recommended for patients with chronic comorbid disease conditions, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, or chronic kidney diseases. This suggests that booster vaccination provided better protection against COVID-19 infection and reduced hospitalisation, ICU admission, and death.40 Interventions specifically designed to address vaccine concerns and the concerns of such patients are of the utmost importance. In turn, this can help to devise proper and well-informed intervention measures to improve vaccine acceptance, considering the growing evidence that booster COVID-19 vaccination is necessary to control the pandemic.41

To the best of our knowledge, there is a dearth of studies employing the HBM to evaluate the intention and hesitancy to receive a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine among patients with comorbid disease conditions in Türkiye. Our findings have the advantage of focusing on individuals belonging to priority groups and highlighting the need to strengthen public opinion and surveillance strategies by gathering information on the reasons for concern and hesitancy regarding a booster dose of COVID-19 vaccines. The present study has some limitations that could be taken into consideration. First, the study was conducted in Istanbul province and did not include other parts of Türkiye, which may not be generalizable to the wider community. Second, the survey was self-reported, and this may have contributed to the inconsistent understanding of questions among some participants, which might lead to a recall bias, and the tendency to report socially desirable responses may potentially lead to falsely reporting one's willingness to get vaccinated.

ConclusionThe present study reveals that the vast majority of patients with chronic comorbid disease conditions who received the COVID-19 vaccine intended to receive a booster dose if necessary, despite any adverse effects from previous doses, which will undoubtedly play a significant role in the control of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, a small percentage of the population expressed hesitancy about receiving the booster dose; therefore, to better control the spread of SARS-CoV-2, effective public health communication messages should be tailored, and building general trust in vaccines may eventually be necessary.

FundingNo specific funding was received.

Authors' contributionsAl-taie A conceived of the study. Al-taie A and Yilmaz ZK reviewed the literature, conducted the quality assessment, and extracted the data. Al-taie A developed the methods and drafted the manuscript. Yilmaz ZK reviewed the data, participated, and supported the data interpretation. Al-taie A was the project manager and advisor on the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.