The Schizophrenia Objective Functioning Instrument (SOFI) is an interviewer-administered scale designed to objectively assess the actual level of patient functioning and to measure community functioning related to cognitive impairment and psychopathology. The aim was to examine the psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the SOFI (Sp-SOFI) in a sample of 155 Spanish outpatients with schizophrenia disorder. The instruments applied were Sp-SOFI, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale (CGI-SCH), Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP), and Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). The discrimination indexes of the Sp-SOFI items range from .21 to .77. Exploratory factor analysis showed an essentially one-dimensional structure. Cronbach's alpha was .93. Test-retest reliability for the Sp-SOFI total score was .87 (p<.001). The canonical correlation between SP-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions was .83. The multiple correlation coefficient between Sp-SOFI domains and GAF score was .84. Sp-SOFI scores were significantly different between high and low scores on the PANSS scales (p<.001). Sp-SOFI measures discriminated among patients with doubtful, mild, moderate, and severe schizophrenia disorder according to CGI-SCH scales (p<.001). New evidence about the validity of the SOFI was provided. The Sp-SOFI is a reliable and valid tool for using in clinical practice.

El Instrumento de Funcionamiento Objetivo para la Esquizofrenia (SOFI) es una entrevista para evaluar el nivel de funcionamiento comunitario en relación con el daño cognitivo y los síntomas psicopatológicos. El objetivo del estudio consistió en examinar las propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la SOFI (Sp-SOFI) en una muestra de 155 pacientes ambulatorios con esquizofrenia. Los índices de discriminación de la Sp-SOFI oscilaron entre 0,21 y 0,77. El análisis factorial exploratorio mostró una estructura esencialmente unidimensional. El alfa de Cronbach fue 0,93. El coeficiente de fiabilidad test-retest fue 0,87 (p<0,001). La correlación canónica entre la Sp-SOFI y la Escala de Funcionamiento Personal y Social (PSP) fue 0,83. El coeficiente de correlación múltiple entre la Sp-SOFI y la Escala de Evaluación de la Actividad Global (EEAG) fue 0,44. Las puntuaciones en la Sp-SOFI fueron significativamente diferentes entre los pacientes con puntuaciones altas y bajas en la Escala del Síndrome Positivo y Negativo (PANSS) (p<0,001). La Sp-SOFI discriminó entre pacientes con trastorno de esquizofrenia dudoso, leve, moderado y grave de acuerdo con la Escala de Impresión Clínica Global de Esquizofrenia (CGI-SCH) (p<0,001). La Sp-SOFI es un instrumento fiable y válido para la práctica clínica.

Schizophrenia is associated with substantial impairments in functional outcomes, including social and occupational functioning, independent living, and the ability to perform activities of daily living (Green, Kern, Braft, & Mints, 2000). Additionally, several studies have shown that cognitive functions are impaired in patients with schizophrenia, and these impairments also have a real impact on the daily functioning of patients with this disorder (García-Portilla et al., 2014; Gavilán & García-Albea, 2014; Menéndez-Miranda et al., 2015). They include significant deficits in memory, attention, problem solving, processing speed, and social cognition, which have been shown to be associated with several of the aforementioned functional impairments (Keefe et al., 2013). This association between cognition and outcome is robust and has been replicated and extended in many countries, using many different types of assessments, in different patient groups across phase of illness (Green & Harvey, 2014). The early detection of these matters is a challenge, particularly with respect to orientation of treatment (Gómez-Benito, Guilera, Pino, Tabarés-Seisdedos, & Marínez-Arán, 2014). One of the greatest difficulties in evaluating this issue is the borderline between negative and cognitive dimensions. It is generally accepted that these two dimensions present similar characteristics with respect to prevalence, difficulty of assessment, progression, prognostic implications, and lack of effective treatments. However, it is also accepted that they constitute two dimensions that are independent but interrelated (García-Portilla & Bobes, 2013; García-Portilla et al., 2015).

The Schizophrenia Objective Functioning Instrument (SOFI) was developed to measure changes in functional outcomes due to patient psychopathology and cognitive impairment. From an initial meeting of experts four domains emerged as most relevant to a functional outcome measure in schizophrenia: 1) living situation (stability, structure/supervision, independence); 2) instrumental activities of daily living (financial management, transportation, medication, treatment, housework/childcare, self-care, shopping, food/cooking, planning and leisure activities); 3) productive activities (work, other vocational oriented activities, treatment-related activities, education, homemaking/childcare); and 4) social functioning (social activity and social support) (Kleinman et al., 2009). Existing measures were reviewed to identify relevant items. One of them was the WHO-DAS-II (Chisolm, Abrams, McArdle, Wilson, & Doyle, 2005), which is directly linked at the level of the concepts to the WHO's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). This provides a framework for understanding the impact of environmental factors on functioning when a person has a health condition. Functioning and disability is increasingly being taken into account in assessing the impact of schizophrenia on the individual, as well as the effectiveness of treatments. Difficulties with everyday activities and low health-related quality of life have consistently been reported as being related to schizophrenia. There is also evidence that the level of impairment in individuals with schizophrenia is closely linked to the support provided by different aspects of the environment, not only the family and the community, but also social services, systems, and policies. The ICF offers a common framework for collecting data on functioning and disability of persons living with schizophrenia (ICF Research Branch, 2015).

The objective of developing the SOFI was to create a functional outcome measure that could be used in clinical trials, psychological treatments and other clinical studies evaluating interventions for cognitive impairment and psychopathology in schizophrenia (Kleinman et al., 2009). This need is strengthened by the fact that The World Health Organization Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 proposes “to strengthen information systems, evidence and research for mental health” including “data about levels of disability, overall functioning and quality of life” (World Health Organization, WHO, 2013).

Scientific societies such as American Psychological Association (APA) or European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations (EFPA) make a strong cause for intervention for patients with schizophrenia (European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations, EFPA, 2014). Psychologists can help people with schizophrenia cope with the difficult effects of the disease, including challenges related to self-care, work, school and relationships (American Psychological Association, APA, 2015). Also, the European Medicines Agency, EMEA (2005) highlight the importance of providing clinicians with adequate, valid, and reliable instruments to measure other outcomes beyond symptoms, in addition to functioning and quality of life.

For all this, we decided to conduct this study in order to validate the Spanish version of the SOFI scale (Sp-SOFI), Spanish being the third most commonly spoken language in the world. To our knowledge, there is no other empirical validation addressing the SOFI. The aims of this study were to translate and culturally adapt the SOFI and examine its psychometric properties in a sample of Spanish outpatients with schizophrenia under standard treatment.

MethodThis instrumental study was carried out using an instrumental, longitudinal design (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007; Montero & León, 2007). The data come from a naturalistic, 6-month follow-up validation study conducted at five sites located in five different cities in Spain. It was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the lead site (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo) and performed in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions (World Medical Association, 2000). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to enrollment.

ParticipantsThe study sample comprised a total of 155 outpatients with schizophrenia. Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study were: age between 18 and 65 years (either sex), diagnosis of schizophrenia (psychiatric diagnosis was made by qualified psychiatrists using ICD-10 criteria), on stable maintenance treatment, and written informed consent to participate in the study. Stability was defined as patients who did not require any change in their current pharmacological treatment during the last three months. The same criterion was applied during the follow up.

Patients with intellectual developmental disorder, acquired brain injury, or who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Instruments and study proceduresFor each patient, demographic data and clinical information regarding diagnosis, medication, and drug use was obtained. Severity of the illness and the level of functioning were assessed. All testing was performed by the same clinician at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

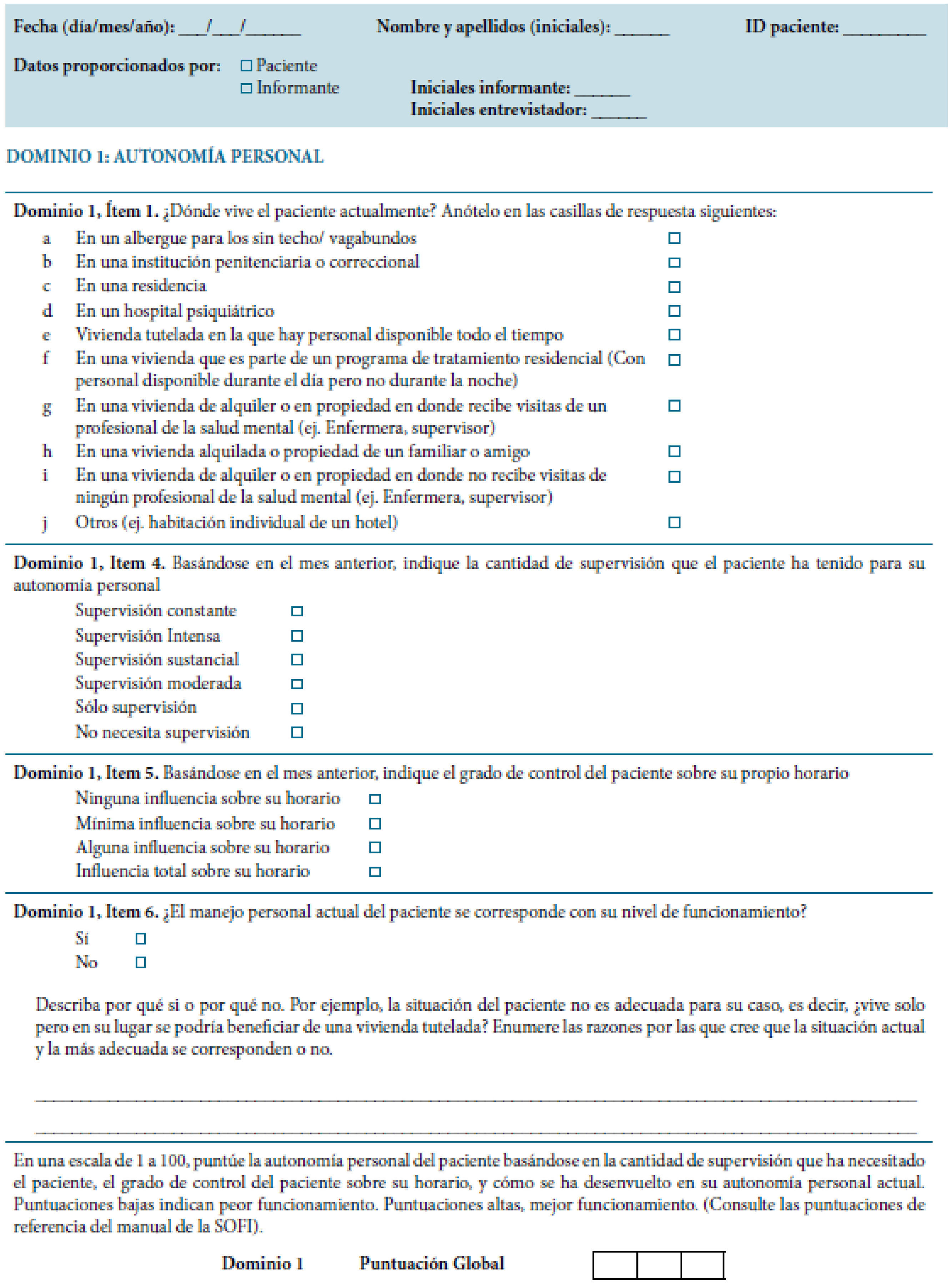

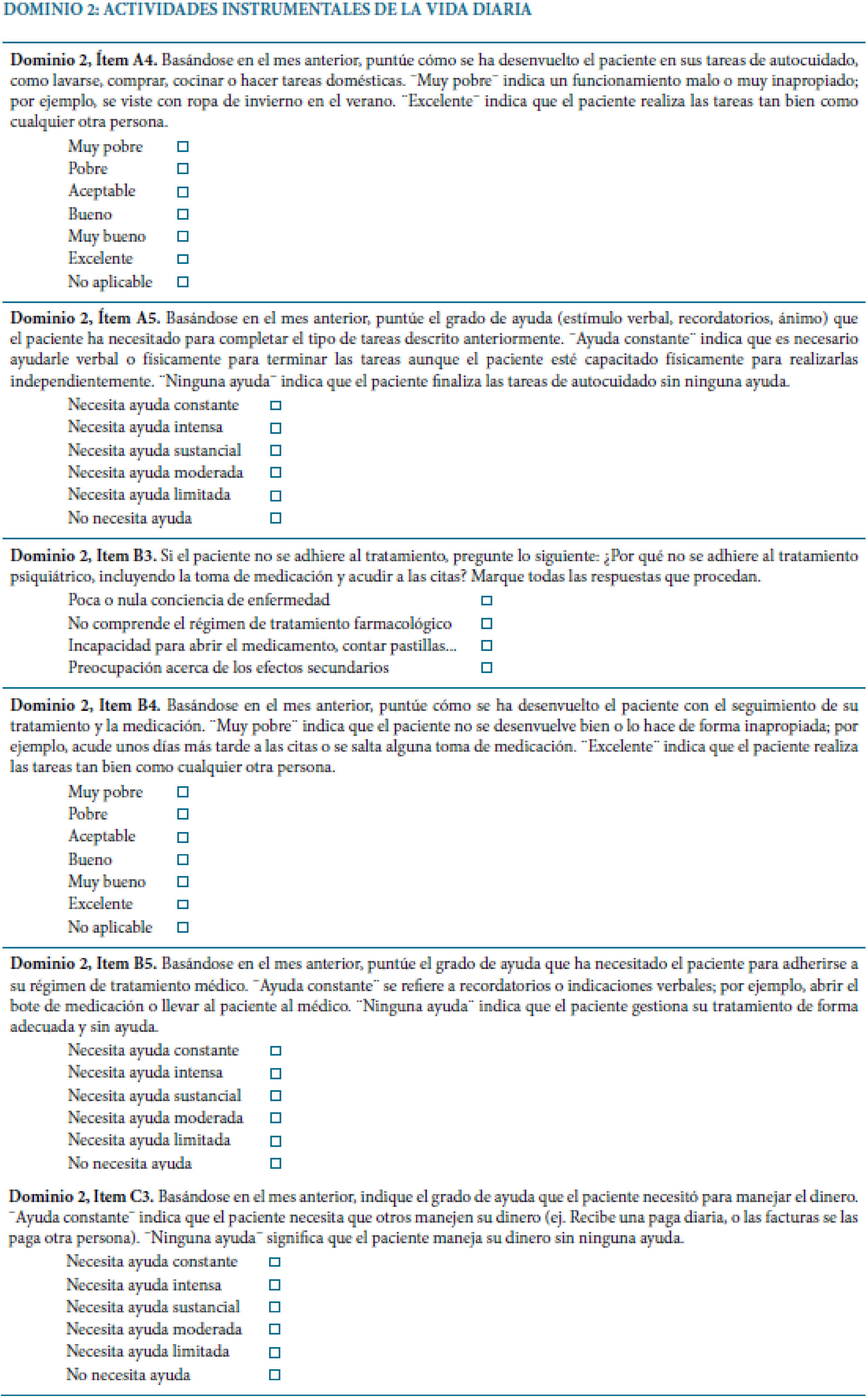

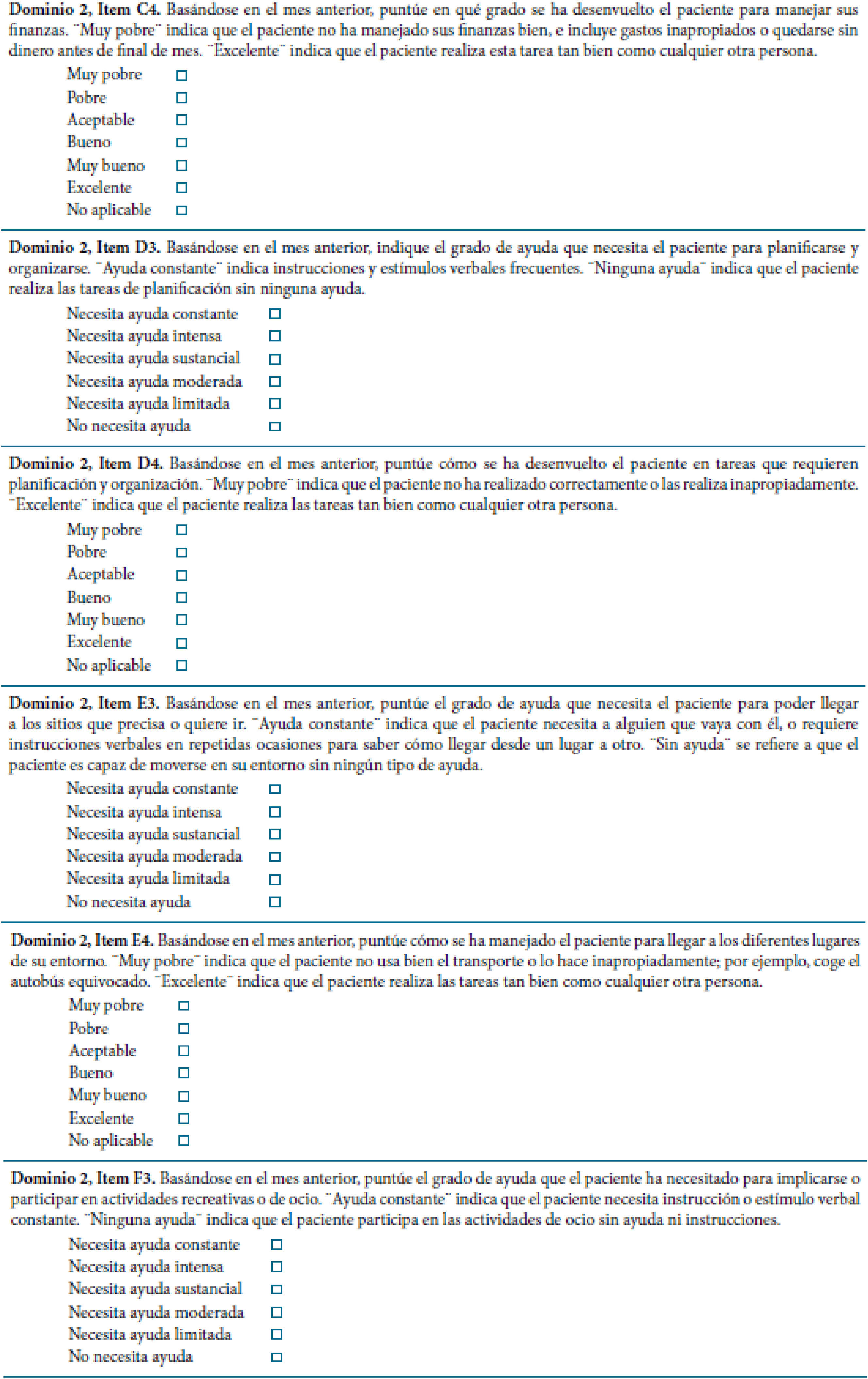

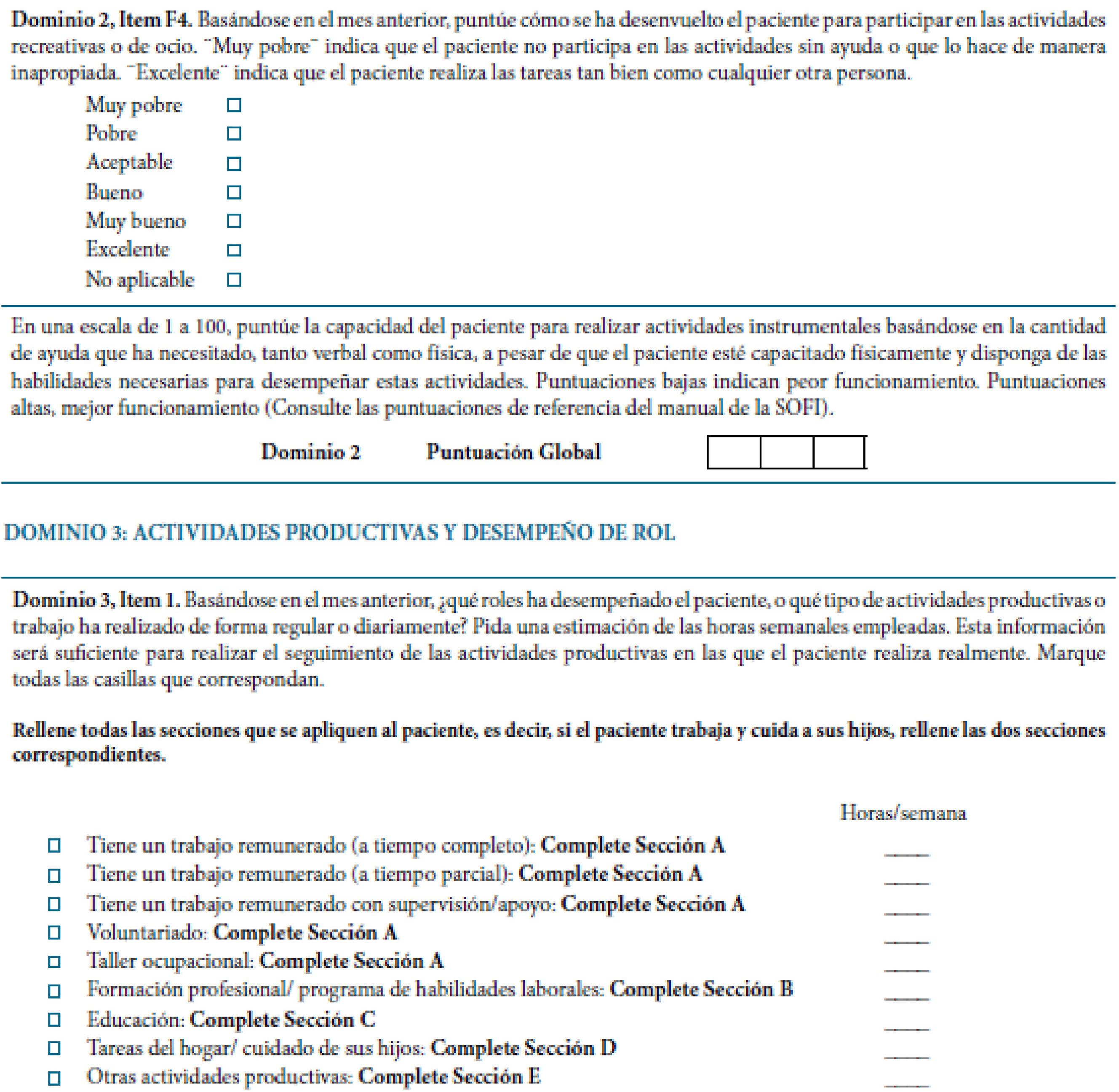

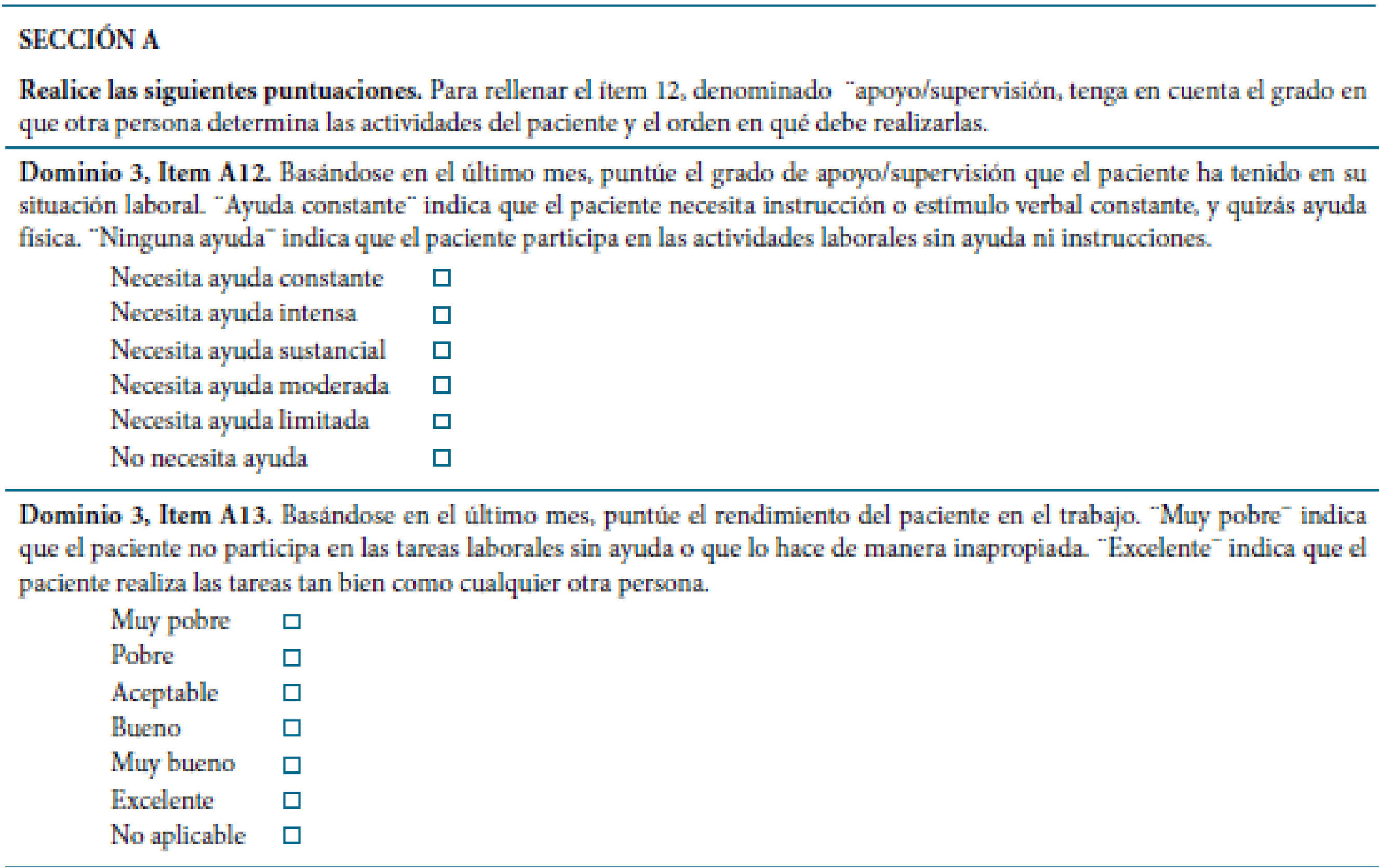

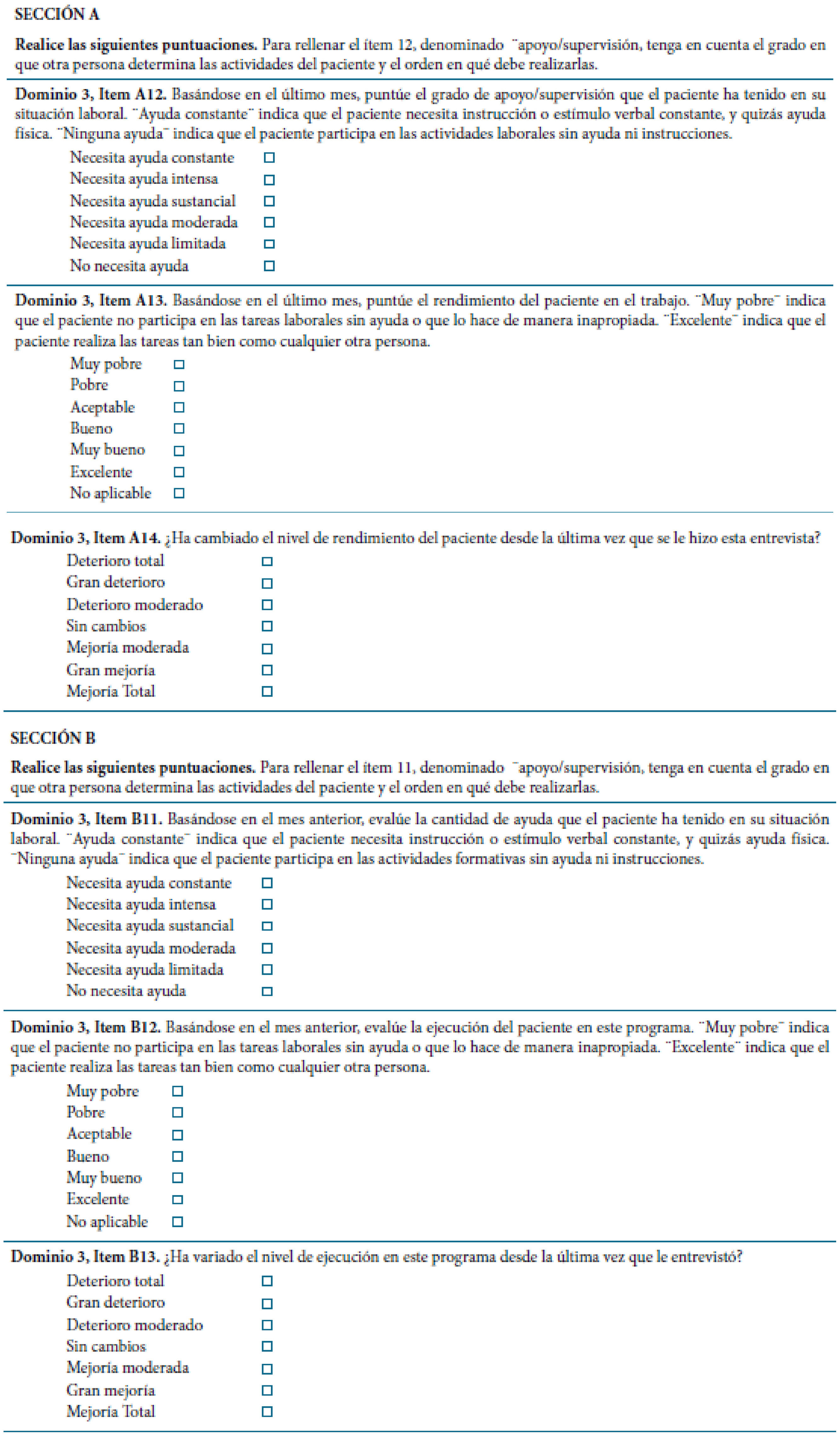

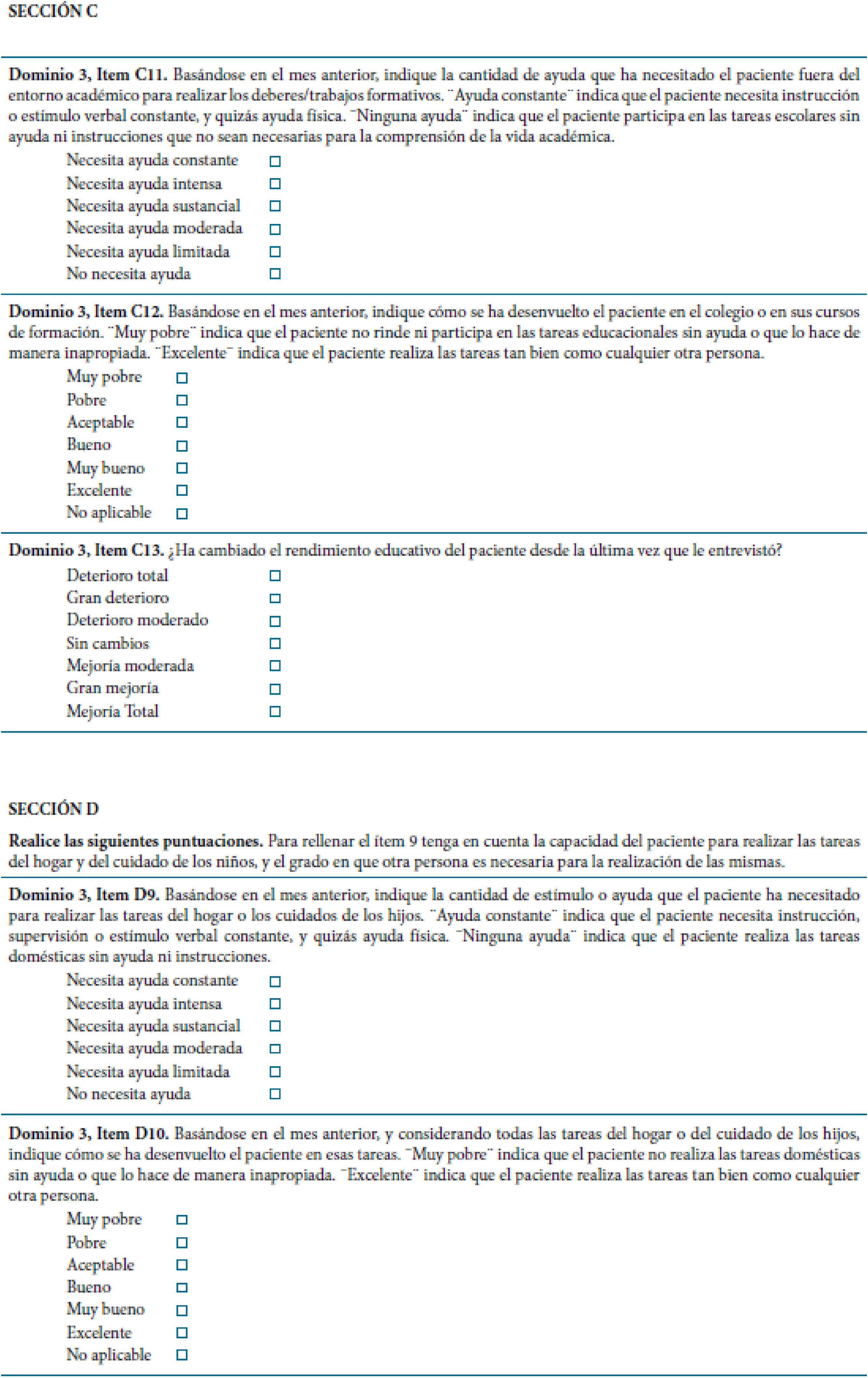

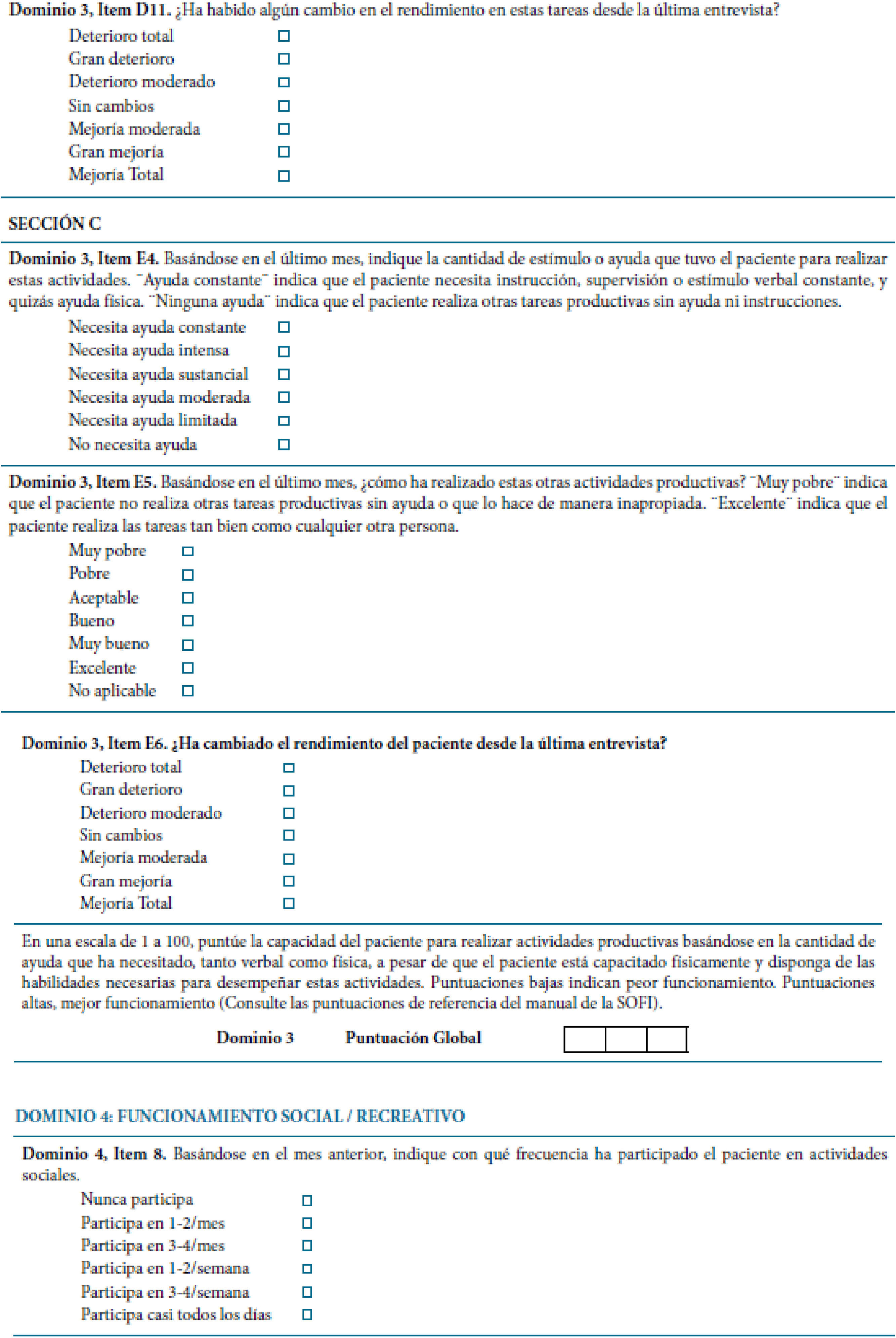

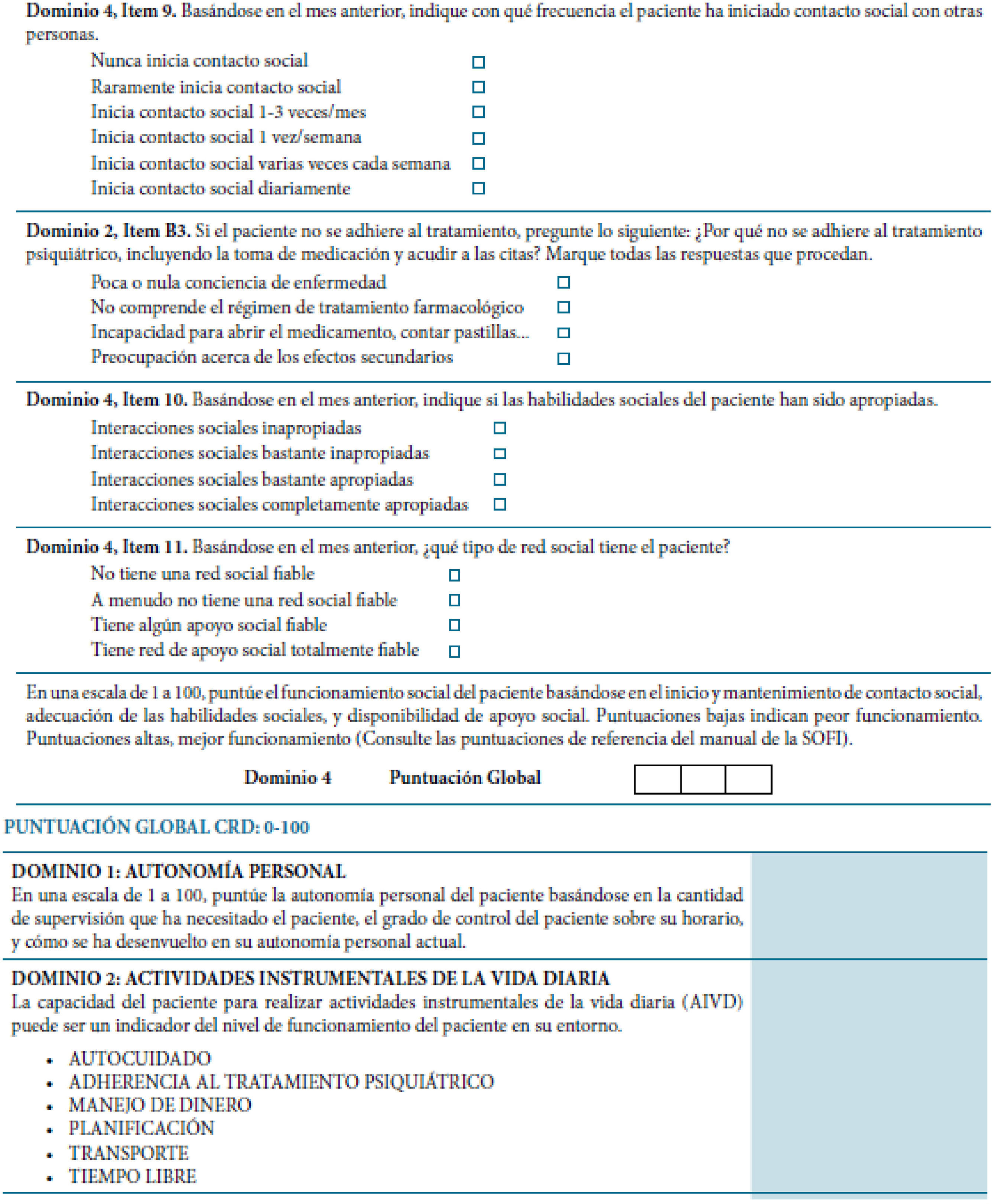

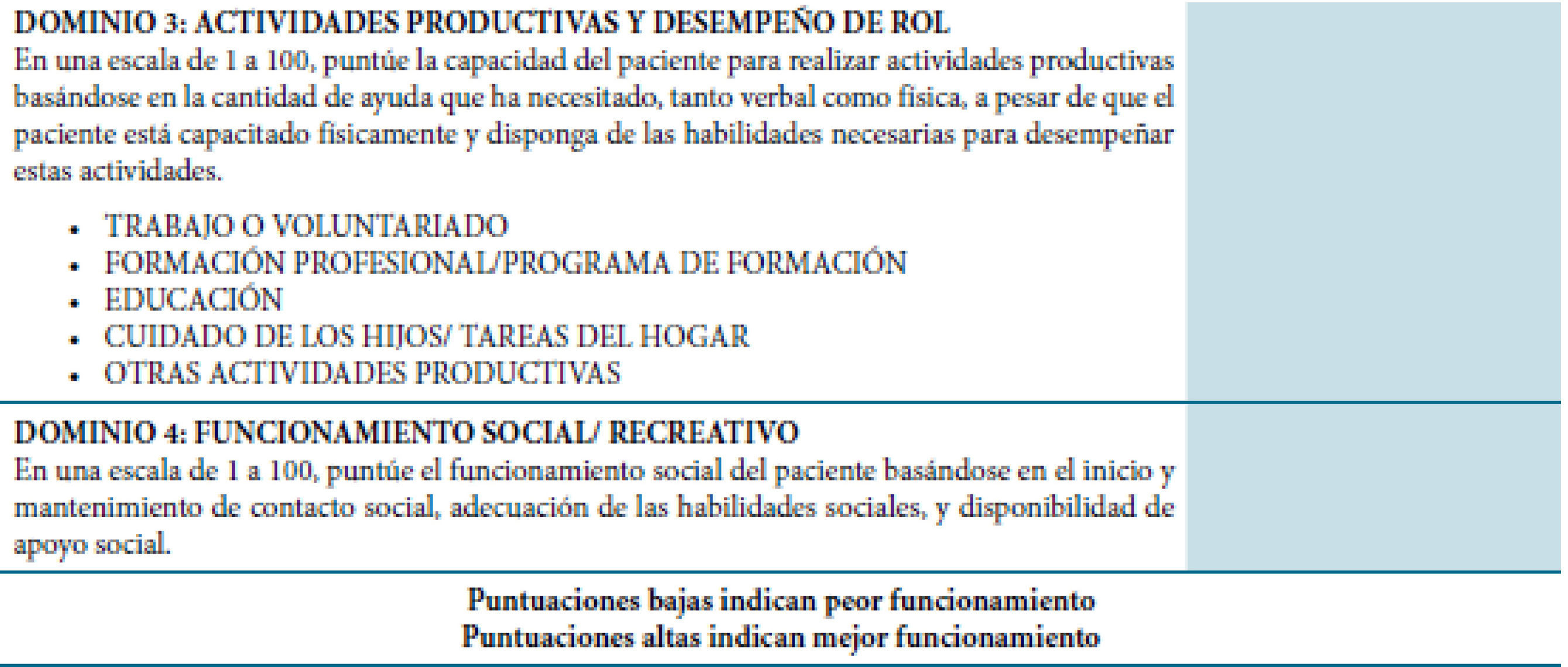

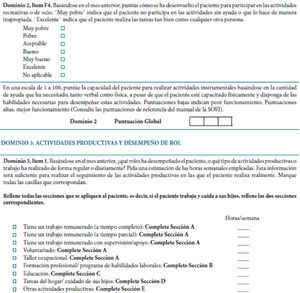

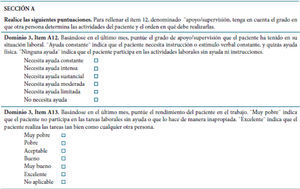

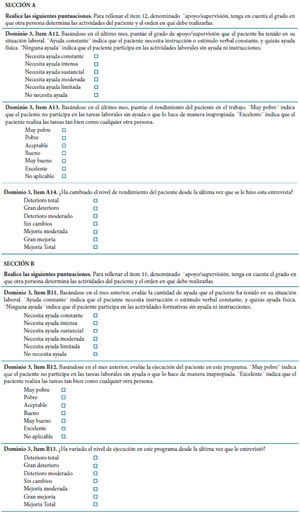

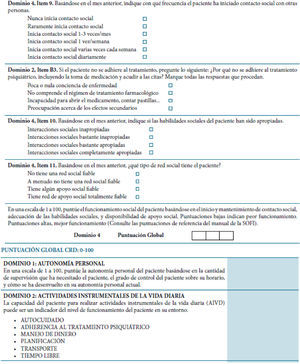

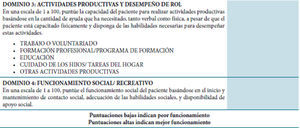

Schizophrenia Objective Functioning Instrument (SOFI). The Schizophrenia Objective Functioning Instrument (SOFI) is an interviewer-administered scale designed to objectively assess the actual level of patient functioning. It is organized into four domains: 1) living situation, 2) instrumental activities of daily living, 3) productive activities, and 4) social functioning (Kleinman et al., 2009). Each domain is rated on a global score of 0 to 100, with anchors provided for each 10 point level. Higher scores indicate better functioning. Prior to completing the global rating, several dimensions are evaluated for each domain using a semi-structured interview format with patients or informants, and including any additional information. In addition, an overall global score is calculated by taking the mean of the four domain global scores. The SOFI was translated following the rules of the International Test Commission (Muñiz, Elosua, & Hambleton, 2013). The original instrument was first translated into Spanish by three independent groups, each one composed of three researchers (psychologists and psychiatrists) who were fluent in English. Each group agreed on a preliminary version. Then, the coordinators of each group approved the final version. Finally, the Spanish version was back-translated by a clinical psychologist. The Spanish version was then pilot tested, by administering it to ten patients to assess its understandability (see Appendix 1).

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay, Fiszbein, & Opler, 1987) was used to evaluate the severity of positive and negative symptoms and general psychopathology in schizophrenia. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (total scores ranging from 30 to 120). Higher scores indicate worse symptoms.

The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale (CGI-SCH) (Haro et al., 2003) was designed to evaluate positive, negative, depressive, and cognitive symptoms, and overall severity in schizophrenia. Each item is rated using a 7-point Likert scale of intensity (from normal to among the most severely ill patients).

The Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP) (García-Portilla et al., 2011) assessed patient functioning in socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing and aggressive behaviors. Regarding these dimensions, higher scores indicate worse level of functioning. An overall global rating is provided, ranging from 0 to 100. Conversely, higher scores indicate better level of functioning.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (American Psychiatric Association, APA, 1987) considers psychological, social, and occupational functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health-illness, excluding impairment due to physical or environmental factors. The ratings range from 1-10 (severely impaired) to 91-100 (superior functioning).

Statistical analysesThe analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0. The two-tailed level of significance used was .05. Demographic and clinical data were evaluated with descriptive statistics, using the mean and standard deviation for the total sample and by sex. Sp-SOFI domain scores were reported separately, and as a percentile rank. Differences relating to the measurements were assessed using Chi-square tests, Student's t-tests, and ANOVA (Duncan's post-hoc test). First of all, in order to determine the psychometric properties of the Sp-SOFI, the discrimination indexes of the items were calculated. The differential item functioning by sex was estimated by logistic regression (Gómez-Benito, Hidalgo, & Zumbo, 2013), and an exploratory factor analysis was carried out using the correlation matrix between Sp-SOFI domains. The unweighted least squares method was used because it showed the best fit of the data to the model. For determining the dimensionality the percentage of explained variance, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and the root-mean-square residual (RMSR) were taken into account. The internal consistency of the translated version was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The test-retest reliability of Sp-SOFI scores was evaluated over an interval of 6 months in the entire sample. The effect of practice on retest performance on the Sp-SOFI was determined by calculating the effect sizes for changes in performance at month 6 (Cohen's d). Convergent validity was studied using the correlation matrix between Sp-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions. The canonical correlation was calculated between both sets of variables. On the other hand, the multiple correlation coefficient between the Sp-SOFI domains and GAF overall score was determined. The expectation was that a moderate to high r correlation would be found for both instruments, as they are functional outcome measures. Also, known-groups validity was calculated, as it was by Kleinman et al. (2009) in the SOFI development. Patients were stratified into two severity groups based on median split of PANSS scores, and Sp-SOFI global scores were compared by severity level using a t-test. The hypothesis was that there would be significant differences in functioning as measured by the Sp-SOFI when patients with more symptoms as measured by the PANSS were compared to patients with fewer symptoms (Kleinman et al., 2009). To determine discriminant validity, patients were classified into four groups based on CGI scores of the Positive, Negative, Cognitive, and Overall Severity Symptoms Scales: doubtful (1- 2), mild (3), moderate (4), or severe (≥ 5) (García-Portilla et al., 2013). To identify statistically significant differences in the Sp-SOFI domain scores according to severity groups in each CGI scale, an ANOVA with Duncan's post-hoc test was calculated. The expectation was that less severely ill patients would have higher Sp-SOFI scores.

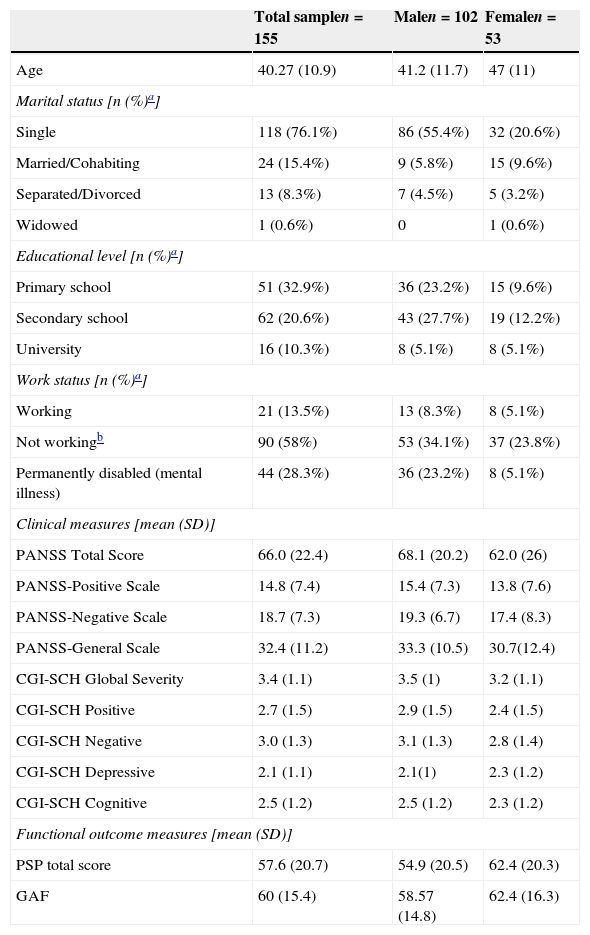

ResultsDemographic and clinical patient characteristicsTable 1 shows the demographic and clinical patient characteristics (total sample and by sex). No significant differences were found according to sex except for marital status (Ӽ2=13.3; p=.004) and work status (Ӽ2=7; p=.029).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total sample and by sex.

| Total samplen=155 | Malen=102 | Femalen=53 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.27 (10.9) | 41.2 (11.7) | 47 (11) |

| Marital status [n (%)a] | |||

| Single | 118 (76.1%) | 86 (55.4%) | 32 (20.6%) |

| Married/Cohabiting | 24 (15.4%) | 9 (5.8%) | 15 (9.6%) |

| Separated/Divorced | 13 (8.3%) | 7 (4.5%) | 5 (3.2%) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.6%) | 0 | 1 (0.6%) |

| Educational level [n (%)a] | |||

| Primary school | 51 (32.9%) | 36 (23.2%) | 15 (9.6%) |

| Secondary school | 62 (20.6%) | 43 (27.7%) | 19 (12.2%) |

| University | 16 (10.3%) | 8 (5.1%) | 8 (5.1%) |

| Work status [n (%)a] | |||

| Working | 21 (13.5%) | 13 (8.3%) | 8 (5.1%) |

| Not workingb | 90 (58%) | 53 (34.1%) | 37 (23.8%) |

| Permanently disabled (mental illness) | 44 (28.3%) | 36 (23.2%) | 8 (5.1%) |

| Clinical measures [mean (SD)] | |||

| PANSS Total Score | 66.0 (22.4) | 68.1 (20.2) | 62.0 (26) |

| PANSS-Positive Scale | 14.8 (7.4) | 15.4 (7.3) | 13.8 (7.6) |

| PANSS-Negative Scale | 18.7 (7.3) | 19.3 (6.7) | 17.4 (8.3) |

| PANSS-General Scale | 32.4 (11.2) | 33.3 (10.5) | 30.7(12.4) |

| CGI-SCH Global Severity | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.5 (1) | 3.2 (1.1) |

| CGI-SCH Positive | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.9 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.5) |

| CGI-SCH Negative | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.4) |

| CGI-SCH Depressive | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.1(1) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| CGI-SCH Cognitive | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| Functional outcome measures [mean (SD)] | |||

| PSP total score | 57.6 (20.7) | 54.9 (20.5) | 62.4 (20.3) |

| GAF | 60 (15.4) | 58.57 (14.8) | 62.4 (16.3) |

Note. SD=standard deviation.

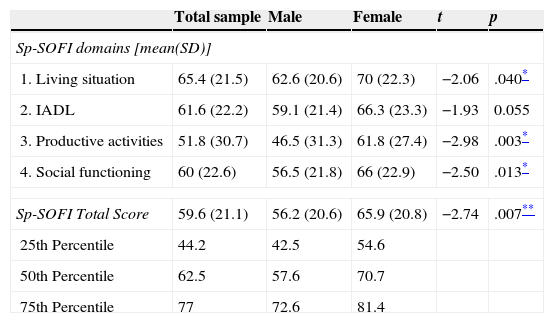

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the Sp-SOFI scores. Statistically significant differences were found in all domains according to sex, except for number 2 (instrumental activities of daily living), with females scoring higher. Table 2 also presents percentile ranks of the Sp-SOFI for the total sample and by sex. It is worth noting here that lower scores are indicative of poorer adjustment. The Sp-SOFI score corresponding to the 25th percentile was 44.2. Scores ranging between 62.5 and 77 corresponded to the 50th and 75th percentiles.

Distribution of Sp-SOFI scores for total sample and by sex.

| Total sample | Male | Female | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp-SOFI domains [mean(SD)] | |||||

| 1. Living situation | 65.4 (21.5) | 62.6 (20.6) | 70 (22.3) | −2.06 | .040* |

| 2. IADL | 61.6 (22.2) | 59.1 (21.4) | 66.3 (23.3) | −1.93 | 0.055 |

| 3. Productive activities | 51.8 (30.7) | 46.5 (31.3) | 61.8 (27.4) | −2.98 | .003* |

| 4. Social functioning | 60 (22.6) | 56.5 (21.8) | 66 (22.9) | −2.50 | .013* |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 59.6 (21.1) | 56.2 (20.6) | 65.9 (20.8) | −2.74 | .007** |

| 25th Percentile | 44.2 | 42.5 | 54.6 | ||

| 50th Percentile | 62.5 | 57.6 | 70.7 | ||

| 75th Percentile | 77 | 72.6 | 81.4 | ||

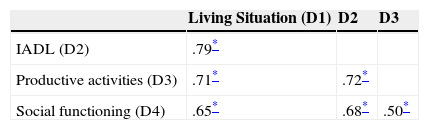

The Sp-SOFI was composed of items with discrimination indexes ranging from .21 to .77. No items presented differential item functioning (DIF) by sex (p<.01; R2<.035). Table 3 shows the correlation matrix between Sp-SOFI domain scores, which were positively and strongly correlated.

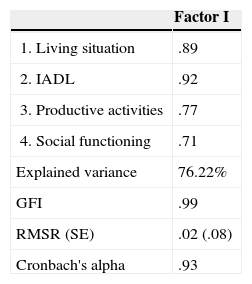

The results obtained in the exploratory factor analysis showed Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) indexes above .80 (Table 4), as well as a statistically significant Bartlett's sphericity index (p<.001). All the factor loadings were in the range of .72 to .92. As can be seen in Table 4, the GFI was above .95, the RMSR was under .08, and the percentage of variance explained by the factor analysis is 76.22%.

Factor analysis of the SP-SOFI domain scores.

| Factor I | |

|---|---|

| 1. Living situation | .89 |

| 2. IADL | .92 |

| 3. Productive activities | .77 |

| 4. Social functioning | .71 |

| Explained variance | 76.22% |

| GFI | .99 |

| RMSR (SE) | .02 (.08) |

| Cronbach's alpha | .93 |

Note. GFI=Goodness of Fit Index; RMSR=Root-Mean-Square Residual; SE=Standard Error.

Sp-SOFI reliability judged by internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) was .93. Test-retest stability between Sp-SOFI domains was also adequate with a Pearson correlation of .80 to .82 (p<.001) after 6 months. For the Sp-SOFI total score, r was .87 (p<.001). Practice effects on the Sp-SOFI were very small (Cohen's d=0.09).

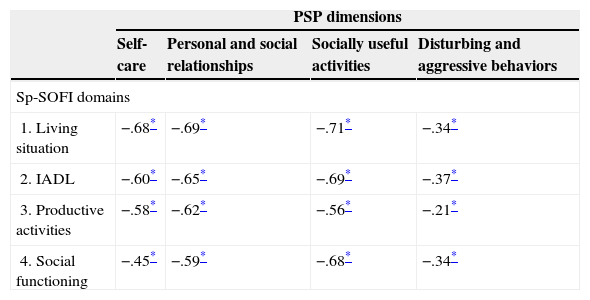

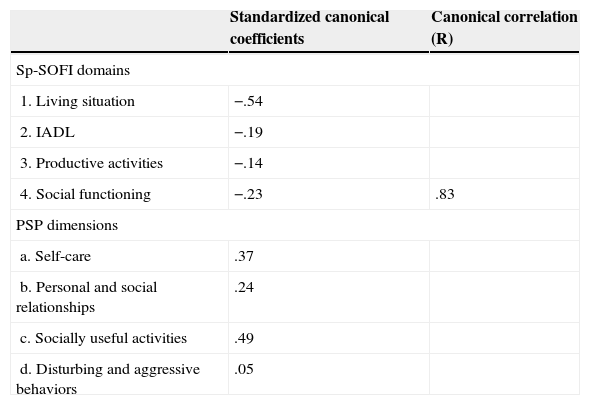

Convergent validityThe Pearson correlation matrix between Sp-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions are shown in Table 5. All the scores were strongly and negatively correlated (p<.001). Note that higher scores in PSP dimensions mean worse level of functioning. Canonical correlation between the two sets of variables is shown in Table 6. As can be seen, the canonical correlation was .83. The Sp-SOFI domain with the highest relevance was “living situation” (domain 1). The multiple correlation coefficient between Sp-SOFI domains and GAF total score was .84, so 71.22% of GAF total variance was explained by Sp-SOFI domains.

Correlation matrix among Sp-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions.

| PSP dimensions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-care | Personal and social relationships | Socially useful activities | Disturbing and aggressive behaviors | |

| Sp-SOFI domains | ||||

| 1. Living situation | −.68* | −.69* | −.71* | −.34* |

| 2. IADL | −.60* | −.65* | −.69* | −.37* |

| 3. Productive activities | −.58* | −.62* | −.56* | −.21* |

| 4. Social functioning | −.45* | −.59* | −.68* | −.34* |

Canonical correlation between the Sp-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions.

| Standardized canonical coefficients | Canonical correlation (R) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sp-SOFI domains | ||

| 1. Living situation | −.54 | |

| 2. IADL | −.19 | |

| 3. Productive activities | −.14 | |

| 4. Social functioning | −.23 | .83 |

| PSP dimensions | ||

| a. Self-care | .37 | |

| b. Personal and social relationships | .24 | |

| c. Socially useful activities | .49 | |

| d. Disturbing and aggressive behaviors | .05 | |

On the other hand, known-groups validity was determined separately for all PANSS subscales (median Positive scale=13; median Negative scale=18; median General scale=30.5). Mean Sp-SOFI total scores were significantly different for the PANSS-Positive based groups (p=.007) and for each domain (p<.005), except for domain 3 (productive activities). Groups based on the PANSS-Negative scale demonstrated statistically significant mean differences for all the Sp-SOFI domains and total score (all p<.001). Likewise, all Sp-SOFI scores also were significantly different between high and low scores on the PANSS-General Psychopathology scale (all p<.001).

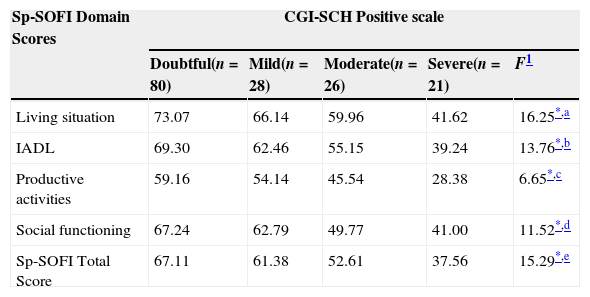

Discriminant validityAll Sp-SOFI measures demonstrate an ability to discriminate among patients with doubtful (CGI=1–2), mild (CGI=3), moderate (CGI=4), and severe (CGI≥5) schizophrenia disorder according to CGI-SCH Positive, Negative, Cognitive, and Overall Severity Symptoms scales (all p<.001). As expected, less severe patients have higher Sp-SOFI scores. Table 7 shows the mean Sp-SOFI domains and total scores for each severity group on each CGI-SCH scale.

Sp-SOFI scores according to schizophrenia severity determined by CGI-SCH scores (ANOVA).

| Sp-SOFI Domain Scores | CGI-SCH Positive scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful(n=80) | Mild(n=28) | Moderate(n=26) | Severe(n=21) | F1 | |

| Living situation | 73.07 | 66.14 | 59.96 | 41.62 | 16.25*,a |

| IADL | 69.30 | 62.46 | 55.15 | 39.24 | 13.76*,b |

| Productive activities | 59.16 | 54.14 | 45.54 | 28.38 | 6.65*,c |

| Social functioning | 67.24 | 62.79 | 49.77 | 41.00 | 11.52*,d |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 67.11 | 61.38 | 52.61 | 37.56 | 15.29*,e |

| CGI-SCH Negative scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful(n=23) | Mild(n=30) | Moderate(n=45) | Severe(n=57) | ||

| Living situation | 77.11 | 68.38 | 54.05 | 46.25 | 20.80*,f |

| IADL | 72.05 | 65.98 | 53.62 | 39.00 | 19.39*,g |

| Productive activities | 65.16 | 57.31 | 34.12 | 32.38 | 12.93*,h |

| Social functioning | 71.32 | 61.47 | 53.55 | 38.42 | 16.78*,i |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 71.34 | 63.28 | 48.83 | 39.01 | 23.54*,j |

| CGI-SCH Cognitive scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful(n=83) | Mild(n=29) | Moderate(n=30) | Severe(n=9) | ||

| Living situation | 71.19 | 64.41 | 58.33 | 41.67 | 7.42*,k |

| IADL | 67.30 | 61.72 | 54.03 | 36.78 | 7.34*,l |

| Productive activities | 57.52 | 51.41 | 43.53 | 35.33 | 2.63*,m |

| Social functioning | 67.27 | 60.17 | 47.30 | 32.56 | 12.45*,n |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 65.73 | 59.43 | 50.80 | 36.58 | 8.57*,o |

| CGI-SCH Depressive scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful(n=94) | Mild(n=39) | Moderate(n=18) | Severe(n=3) | ||

| Living situation | 68.72 | 62.99 | 51.72 | 75.00 | 3.67**,p |

| IADL | 64.97 | 60.09 | 46.28 | 65.33 | 3.81 |

| Productive activities | 56.42 | 45.58 | 38.17 | 60.33 | 2.53 |

| Social functioning | 62.87 | 63.35 | 39.33 | 42.00 | 7.10*,q |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 63.14 | 58.00 | 43.88 | 60.67 | 4.50 |

| CGI-SCH Overall Severity scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doubtful(n=34) | Mild(n=47) | Moderate(n=47) | Severe(n=27) | ||

| Living situation | 80.71 | 73.35 | 59.62 | 41.11 | 33.99*,r |

| IADL | 76.68 | 68.67 | 54.83 | 41.78 | 21.45*,s |

| Productive activities | 69.65 | 61.61 | 42.72 | 26.00 | 16.84*,t |

| Social functioning | 73.50 | 68.03 | 51.94 | 43.04 | 16.93*,u |

| Sp-SOFI Total Score | 75.13 | 67.91 | 52.28 | 36.92 | 33.18*,v |

Note.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Mildly ill differed from doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately and mildly ill differed from doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

Severely ill patients differed from moderately, mildly, and doubtfully ill patients. Moderately ill differed from mildly and doubtfully ill.

This paper reports the first validation of the Schizophrenia Objective Functioning Instrument (SOFI) in a sample of patients with schizophrenia receiving standard maintenance treatment in Spain. We found good psychometric properties, which confirm the Sp-SOFI as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing functioning in daily clinical practice.

All the Sp-SOFI items have shown good psychometric properties, including adequate discrimination indexes (Muñiz, Fidalgo, García-Cueto, Martínez, & Moreno, 2005) and no differential item functioning by sex (Gómez-Benito et al., 2013). Exploratory factor analysis showed that the four domains have an essentially one-dimensional structure (Kline, 2005). In addition, the high internal consistency (α=.93) of the Sp-SOFI permits the definition and assessment of a global factor that groups these four domains. These results add new evidence of validity to the previous report (Kleinman et al., 2009).

Test-retest reliability was good (from .80 to .82) for all the Sp-SOFI domains, especially in view of the fact that the interval period in our study was only 6 months. With respect to the impact of practice on Sp-SOFI performance, a very small effect size was found in our patients. This data are similar to those reported by Kleinman et al. (2009). In this sense and regarding to the reliability, we believe now that also would have been interesting to study the inter-rater reliability, due to the role of judgment in the SOFI scoring. This issue would be an area for further research.

Evidence supporting convergent validity was good. As expected, correlations between Sp-SOFI domains and PSP dimensions were high due to the conceptual overlap of the instruments. As previously reported by Kleinman et al. (2009), the PSP measures patient functioning in several areas was similar to the SOFI. In fact, the canonical correlation coefficient between the two sets of variables was 0.83, which indicates that convergent validity of the Sp-SOFI is excellent according to the model of EFPA for the evaluation of the quality of tests (Evers et al., 2013). Additionally, the multiple correlation coefficient between the Sp-SOFI domains scores and the total score on the GAF was, as expected, positive and strong in magnitude, thus confirming the hypothesis that the Sp-SOFI measures functional outcomes.

Continuing with the construct validity, we found very similar data to those reported by Kleinman et al. (2009) regarding the SOFI ability to differentiate between patients with a high and low degree of psychopathology. Patients with more impairment in clinical symptoms on all PANSS scales (positive, negative, and general) were rated as having worse functional outcomes using the Sp-SOFI. In this regard, we think that these data do not demonstrate the ability of the SOFI to measure the link between cognition and functioning–as designed by Kleinman et al., 2009–but the relationship between symptomatic domains and cognitive domains is strong (Lin et al., 2013). Negative symptoms are found to have the strongest relationship with cognition; they produce the greatest impact on functioning, life-style habits, and somatic health of the individuals manifesting them. Numerous studies have shown a positive correlation between the seriousness of negative symptoms and deterioration in patient social, family, and work functioning (García-Portilla & Bobes, 2013). Nevertheless, a weak association was also noted with positive symptoms such as reality distortion, as well as depressive symptoms with cognition. The relationship among cognition, clinical symptoms, and functional outcome is complex and it is important to take all these factors into account simultaneously while investigating their interactions (Lin et al., 2013). In this regard, Green and Harvey (2014) have suggested that functional capacity and cognitive skills may both reflect a broader common trait called “ability.” Several studies with different samples have suggested that there may be one ability trait that cuts across tasks labeled “neurocognitive” and those designated “functional” (Green & Harvey, 2014).

On the other hand, regarding discriminant validity, the Sp-SOFI is able to discriminate among degrees of mental disorder severity in the expected direction. In general terms, patients with severe mental disorders obtained significantly lower scores than the other three groups, while patients with mild mental disorders obtained significantly higher scores than the other groups (it should be remembered that higher Sp-SOFI scores indicate better functioning). In addition, severely ill patients generally scored significantly lower than moderately and mildly ill patients and, in turn, moderately ill patients scored significantly lower than those mildly or doubtfully ill. This score gradient is especially remarkable for the CGI-SCH-Cognition scale, given the link between cognition and functional outcomes that SOFI aims to make, and has also been found for all CGI-SCH scales, except the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and productive activities of the CGI-SCH-Depressive scale. This may be explained by the fact that the sample distribution is very irregular in CGI-SCH-Depressive scores. In fact, ninety-four patients scored doubtful, while only three scored severe. This does not allow any conclusions in this respect.

Regarding the clinical characteristics of our patients sample, PANSS scores were reflective of a stable non-acute population with a mean score of 14.7 (SD=7.4) on the Positive scale and 18.7 (SD=7.3) on the Negative scale. This means values were similar to those reported by other studies in patients with schizophrenia, such as 17.1 (SD=5.8) and 18.7 (SD=6.5) reported by Kleinman et al. (2009), and 18.2 (SD=7.7) and 2.0 (SD=9.1) reported by Haro et al. (2003), on Positive and Negative scales respectively.

Finally, there is the conversion of the Sp-SOFI total scores to principal percentiles as established in order to compare an individual's position relative to the distribution of the sample as a whole. In our opinion, patients in the ≤25th percentile should be considered the at-risk group, in the sense that the clinician should comprehensively take into account the problems associated with a poor functioning. In this regard, it should be noted that the female subsample had higher scores (better functioning) on the Sp-SOFI than males. Similarly, both PANSS and CGI-SCH scores are higher in males, meaning greater symptom severity. Likewise, scores on functional outcome measures (PSP and GAF) were higher (better functioning) in the female group. This means that the scores found on the Sp-SOFI are consistent with the other measures and adjusted to the clinical characteristics of the sample.

The external validity of this study can be considered good since the patients included are similar to stable outpatients who are on treatment for schizophrenia in daily clinical practice throughout Spain. The study inclusion and exclusion criteria were non-restrictive and patients from five different cities in Spain were included in the study. However, as Kleinman et al. (2009) reported, further research is needed to examine measurement qualities in different and larger schizophrenia samples. This sample may not be generalizable to unstable patients enrolled in clinical trials. Additional research on more heterogeneous samples of schizophrenia patients is required to draw conclusions about psychometric performance across a broader spectrum of disease severity (Kleinman et al., 2009).

In addition to all that has been already said, three limitations should be taken into account when interpreting this study. First, although the CGI-SCH Cognition Scale was used as a measure of cognition, there is no performance data from a cognitive battery. In this sense, it would have been interesting to use the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS), as was done by Kleinman et al. (2009) in their study. Second, is the lack of a control group. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the sensitivity of the Sp-SOFI to changes related to an intervention. Third, the sample size of this study was quite modest. From psychometric and statistical perspective, larger samples would be necessary to obtain stronger and more stable conclusions about the SOFI. In this sense, it would be advisable to perform replication studies, as well as extensions to a broader range of samples of patients with schizophrenia.

In summary, in light of the global data, we are able to demonstrate that the Spanish version of the SOFI (Sp-SOFI) is reliable and valid for measuring functioning in patients with schizophrenic disorders. Also, new evidence about the validity of the instrument was provided. As a performance-based, clinician-rated instrument, the Sp-SOFI seems to be appropriate for use in clinical practice as a means of monitoring functioning in this population.

FundingThis study was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental, CIBERSAM.

We would like to thank Francisco Rodriguez-Pulido, Maria Jose Jaen-Moreno, Francisco Toledo, Carmen Alcaraz, Cesar Pereiro, and Alberto Duran for their participation as raters.