Background/Objective: Prolonged stress can overwhelm coping resources, leading people to seek mental health care. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is an intervention that enhances well-being and reduces distress, assumedly by means of increasing psychological flexibility (PF). We examined the association between a total increase in PF during an intervention and decreases in stress and increases in well-being during and after the intervention. Method: The intervention was a randomized controlled trial of an ACT-based self-help intervention. Participants were 91 individuals reporting elevated levels of work-related stress. Measurements were completed at preintervention, postintervention, and 3-month follow-up. Results: Structural equation models revealed that the total increase in PF during the intervention was negatively associated with a decrease in stress (b=-0.63, SE=0.14, p<.001) and positively associated with an increase in well-being during the intervention (b=0.48, SE=0.11, p<.001), but not with a decrease in stress (b=0.03, SE=0.27, p>.05) and well-being (b=-0.04, SE=0.39, p>.05) following the intervention. Conclusions: Our study provides empirical support for decreasing stress and promoting well-being through ACT and emphasizes the potential of PF in promoting well-being.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: El estrés prolongado puede inhibir los recursos de adaptación, llevando a las personas a solicitar servicios de salud mental. La Terapia de Aceptación y Compromiso (ACT) es una intervención que fomenta el bienestar y reduce la ansiedad, presuntamente mediante el aumento de la flexibilidad psicológica (PF). Examinamos la asociación entre un aumento total en PF durante una intervención y el descenso del estrés y el aumento del bienestar durante y después de la intervención. Método: En un ensayo aleatorio controlado de una intervención de autoayuda con base en ACT participaron 91 individuos con niveles elevados de estrés laboral. Completaron mediciones pre, post y seguimiento a tres meses. Resultados: Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales revelaron que el aumento total en PF durante la intervención está negativamente asociado a la reducción del estrés (b=-0,63, SE=0,14, p<0,001) y positivamente asociado con el aumento del bienestar durante la intervención (b=0,48, SE=0,11, p<0,001), pero no con el descenso del estrés (b=0,03, SE=0,27, p>0,05) y el bienestar (b=-0,04, SE=0,39, p>0,05) después de la intervención. Conclusiones: Se proporciona base empírica de la reducción del estrés y el fomento del bienestar mediante ACT, enfatizando el potencial de PF para fomentar el bienestar.

Nearly everyone experiences stress in daily life, such as work deadlines, family arguments or being late for an appointment. These stressors can have a strong impact on well-being (Almeida, 2005; Schönfeld, Brailovskaia, Bieda, Zhang, & Margraf, 2016; Thoits, 2010). One particular deleterious type of stress is related to work. People who work may experience a substantial level of work-related stress (Eurofound, 2005). In one U.S. report, 40% of all professionals stated that their job is very or extremely stressful (American Psychological Association Center for Organizational Excellence, 2014). Work-related stress is associated with increased absenteeism and reduced efficiency at work and large costs for society (Henderson, Glozier, & Elliott, 2005; Kalia, 2002; Sultan-Taïeb, Chastang, Mansouri, & Niedhammer, 2013). Further, prolonged stress can lead to stress related disorders, which is subject to the Eleventh Revision of International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) (Keeley et al., 2016; Maercker et al., 2013). Also it has been associated with a range of adverse health outcomes, such as anxiety and depression (Fawzy & Hamed, 2017; Herr et al., 2017; Melchior et al., 2007; Tennant, 2001), coronary disease (e.g. Li, Zhang, Loerbroks, Angerer, & Siegrist, 2014), and sleep problems (e.g. Faber & Schlarb, 2016).

Challenges of prolonged stress may at times exceed a person's capacity to cope effectively, and this is when mental health care may be sought. However, traditionally, the focus in mental health care has been on treating mental disorders and symptoms rather than promoting well-being (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). It has been recognized that mental health is more than simply the absence of mental illness. For instance, it has been addressed in the two-continua model of mental health that states that positive mental health or well-being is related to, but different from mental illness (Keyes, 2005). Well-being can be broken down into emotional, social, and psychological well-being (Diener, Napa Scollon, & Lucas, 2009; Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999; Ryff, 1989). Emotional well-being refers to feelings of happiness and (life) satisfaction. Psychological well-being refers to living a rich life, in which one's abilities are taken into account. Social well-being refers to the feeling that one values and is valued by the society in which one lives.

Prior studies with population-based samples investigating the interdependence of well-being and psychopathology (Keyes, 2007; Lamers, Westerhof, Glas, & Bohlmeijer, 2015; Trompetter, de Kleine, & Bohlmeijer, 2016) showed that well-being protects against mental illness through components such as positive relationships with others, autonomy, and environmental mastery. Two such studies showed that well-being over time buffers against mental illness and disease later in life (Grant, Guille, & Sen, 2013; Lamers et al., 2015). The latter showed that a decrease in psychopathology was linked to improved well-being, and a decrease in well-being was linked to higher levels of psychopathological symptoms. Another study indicated that low well-being was strongly associated with depression 10 years later (Wood & Joseph, 2010), and another found that changes of levels of well-being were related to the prevalence and incidence of mental illness in a 10-year time span (Keyes, Dhingra, & Simoes, 2010). In sum, findings consistently support the two-continua model and indicate the relevance of well-being for mental health care.

The two-continua model and existing studies about the impact of well-being indicate the need for interventions that explicitly promote well-being (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999, 2012; Keyes, 2007). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a cognitive behavioral therapy, which may fit well with mental health promotion, and one of the central goals of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility (PF). PF is the ability to adapt to a variety of different situational demands when doing so is useful for living a meaningful life, and it is thought to be an important mechanism of change during ACT interventions (Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006). Acceptance and mindfulness are core processes of PF (Baer et al., 2008; Carmody & Baer, 2008; Soysa & Wilcomb, 2015). Another crucial focus is valued action and behavior change processes. Pursuing one's values has been found to be related to well-being and functioning, for instance, in mental health professionals (Veage et al., 2014), students (Sagiv & Schwartz, 2000), and (treatment-resistant) patients (Gloster, Sonntag, et al., 2015; Wersebe et al., 2016). Research has demonstrated that ACT is effective in promoting well-being (e.g., Bohlmeijer, Fledderus, Rokx, & Pieterse, 2011; Bohlmeijer, Lamers, & Fledderus, 2015; Fledderus, Bohlmeijer, Smit, & Westerhof, 2010). Though not always linear, results of an ACT effectiveness trial indicate that well-being improved in the ACT group compared to the control group from preintervention to postintervention and follow-up (Fledderus et al., 2010). Studies that examined guided self-help over the Internet aiming at increasing positive mental health found that over the course of therapy, participants reported significant improvements in all three aspects of well-being (e.g., Bohlmeijer et al., 2015; Fledderus, Bohlmeijer, Pieterse, & Schreurs, 2012). These findings indicate that change processes in acceptance and valued action are beneficial for an engaged and meaningful life (Hayes et al., 1999, 2012). Taken together, there are solid indications for the association of PF, and its increase through ACT, and well-being.

Enhancing PF has also been shown to be effective in reducing stress (e.g., Brinkborg, Michanek, Hesser, & Berglund, 2011; Dahl, Wilson, & Nilsson, 2004; Flaxman & Bond, 2010). Results in the treatment of social workers, for instance, show that stress decreased in an intervention group compared to a control group and that pre- to posttreatment changes in PF were linked to these decreases in stress (Brinkborg et al., 2011). One study's finding showed pre–post reductions in distress following an ACT intervention (Flaxman & Bond, 2010). Importantly, an increase in PF following the intervention resulted in reduced distress among working individuals. Research indicates that participants not only decreased in their stress levels but also in sick leave utilization (Dahl et al., 2004). In short, individuals with symptoms of work stress might especially benefit from ACT, as this intervention changes the focus from symptom reduction to engagement in acceptance and mindfulness (Carmody & Baer, 2008; Soysa & Wilcomb, 2015) and valued behaviors (Clarke, Kingston, James, Bolderston, & Remington, 2014; Gloster, Sonntag, et al., 2015)—core PF processes.

The purpose of the present study was to examine an increase in PF and its association with decreases in stress and increases in well-being during and following a self-help intervention based on ACT. In this study, a sample of individuals with heterogeneous occupations and with at least moderate levels of stress read an ACT self-help book. We hypothesized that a change in PF during the intervention (i.e., preintervention to postintervention) would be associated with (1) decreases in stress during the intervention (i.e., pre-intervention to post-intervention), and after the intervention (i.e., postintervention to followup), and (2) increases in well-being during (i.e., preintervention to postintervention), and after (i.e., postintervention to followup) the intervention.

MethodDesign and procedureData were collected in an online randomized controlled trial comparing an ACT group to a waiting list (WL) control group for individuals with at least moderate levels of stress (Hofer et al., 2017). Participants were randomized to immediate intervention or one of two WL groups. Participants in the immediate intervention received a self-help book with weekly reading assignments and weekly assessments. The WL groups differed with respect to the presence (WL+) versus absence (WL−) of a weekly measurement of PF during their intervention. Participants in the WL− group were not contacted during the waiting period or the intervention. For this study, data of the participants in the WL− group were used only after they received treatment. After the waiting period, participants in the WL groups received the self-help book. Follow-up for all participants took place 3 months after the 6-week-intervention. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and full informed consent was secured from all participants.

ParticipantsParticipants were recruited via a newsletter of a German health insurance company sent to members nationwide who were eligible for inclusion if they had an elevated score of 17 or more on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). This value was chosen as it marks the mean of a normative adult population (Cohen & Janicki-Deverts, 2012) and has been used in several other studies (e.g., Brinkborg et al., 2011). This cut-off value assured that participants had a moderate or greater stress level. Individuals who were currently in psychotherapy treatment or showed clinically significant suicidal intent as indicated by a score greater than 1 on Item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) were excluded. For the present study, the immediate intervention group and the WL+ were used, as participants in these groups filled out the weekly measure of PF relevant for the present study. In total, 133 participants were included in the study, of which 92 filled out the weekly measure on PF. We included 91 in our analysis (due to missing data).

InterventionParticipants received the self-help book Burnout: mit Akzeptanz und Achtsamkeit den Teufelskreis durchbrechen (Burnout: Break the Vicious Cycle with Acceptance and Mindfulness; Waadt & Acker, 2013a). The intervention was delivered with no therapist contact. The book consists of 11 chapters and presents processes and techniques stemming from ACT. After each chapter participants were asked to complete practical exercises. Audio instructions for ACT processes were available for download on the book's website (Waadt & Acker, 2013b). To complete the book in 6 weeks, chapters were assigned in sections.

MeasuresParticipants completed measures at preintervention, postintervention, and follow-up. The ACT group (immediate intervention) and the WL+ group also completed weekly measurements during the intervention to assess PF. All questionnaires were administered online.

Mental Health Continuum—Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2005). The MHC-SF is a 14-item questionnaire that measures well-being scaling from 1 (never) to 6 (every day). Respondents rated their emotional well-being (3 items), social well-being (5 items), and psychological well-being (6 items) over the last month. For each aspect of well-being a mean score across the individual items was computed. Higher scores indicate greater well-being (Keyes, 2005; Lamers, Westerhof, Bohlmeijer, ten Klooster, & Keyes, 2011). The MHC-SF has demonstrated good psychometric properties across various age groups and nations (Lamers et al., 2011; Westerhof & Keyes, 2010).

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983). The PSS is a 10-item self-report measure of perceived stress in certain situations. Higher scores indicate higher perceived stress levels (0–40 points). The PSS has shown good validity and reliability (Cohen et al., 1983).

Open and Engagement State Questionnaire (OESQ; Benoy, Knitter, Doering, Knellwolf, & Gloster, 2017). The OESQ is a one-dimensional measure that captures PF across 4 items considerating all six processes of ACT (acceptance, defusion, present moment, self-as-context, values and committed action), referring to its core processes, referring to its core processes. Higher scores indicate higher PF (0–4 points). A study on the psychometric properties of the OESQ in patients with panic disorder with agoraphobia and individuals with burnout indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach's (α=.87) (Benoy et al., 2017).

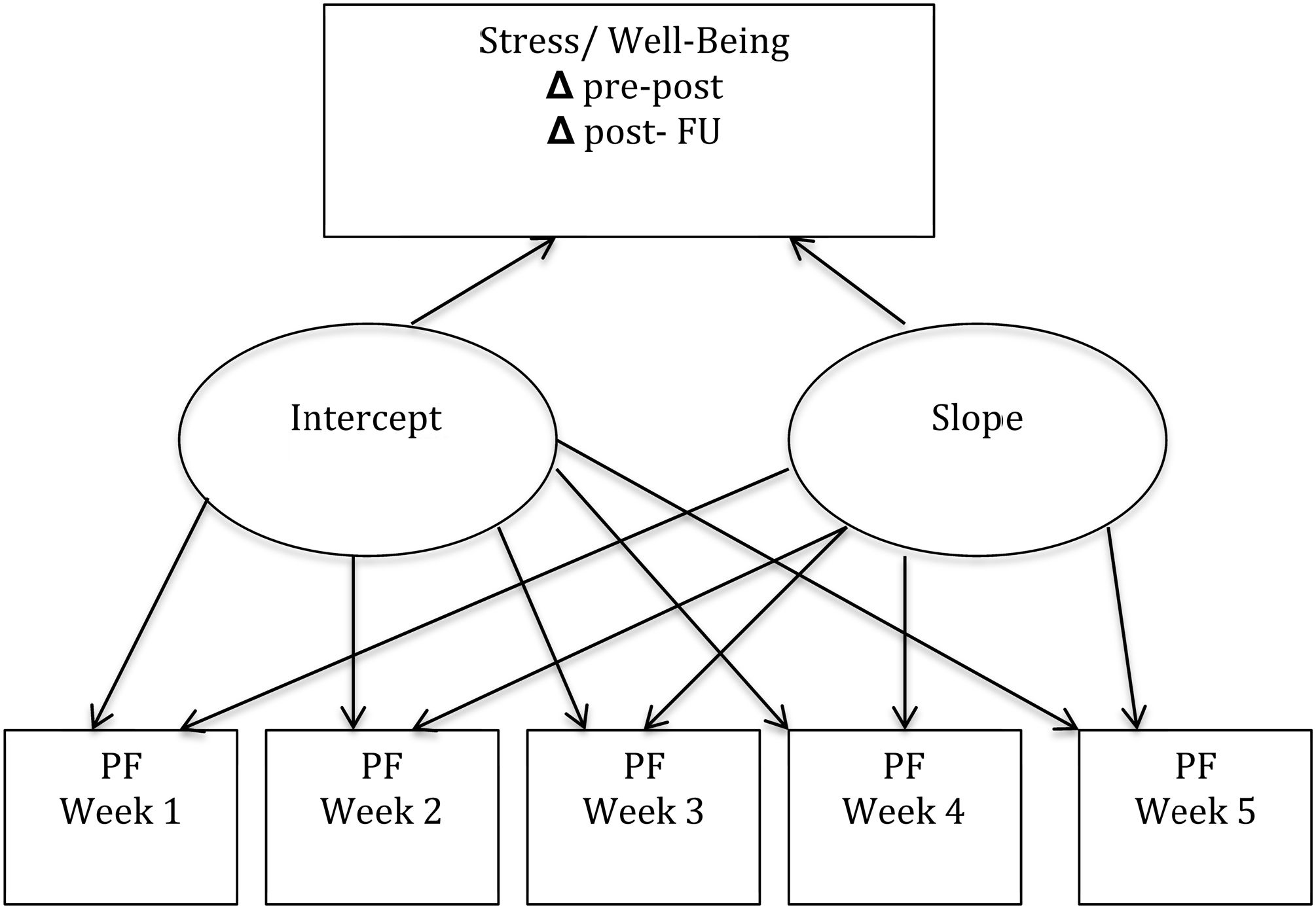

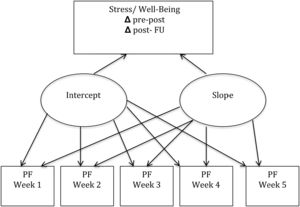

Statistical analysisData were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0 and Mplus version 6.12 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Hypotheses were tested with structural equation models, specifically latent growth curve models (LGMs; Heck & Thomas, 2015) (see Figure 1). LGMs are suitable for analyzing the nested structure of repeated measures data within a person and take advantage of the statistical power of analyzing multiple time points (Muthén & Curran, 1997). LGMs can incorporate incomplete cases in the analyses by using full-information maximum-likelihood estimation. Growth is described here using two parameters from the LGM, the intercept and the slope. The intercept is the score at a set time point—in this case the first week after preintervention. The linear slope is the average growth rate between repeated measurements of PF between pre- and postintervention. To test our assumptions that an increase in PF between preintervention and postintervention would be associated with pre–post decreases in stress and increases in well-being, we correlated the slope coefficient of PF from the LGM with the difference scores of stress and well-being. We used a correlation approach because PF was concurrently measured with stress or well-being between pre- and postintervention. To test our hypothesis that an increase in PF between pre- and postintervention would be associated with decreases in stress and increases in well-being between postintervention and follow-up, we regressed difference scores of well-being and stress on the slope coefficient of PF. The α level for statistical significance for all analyses was set to .05.

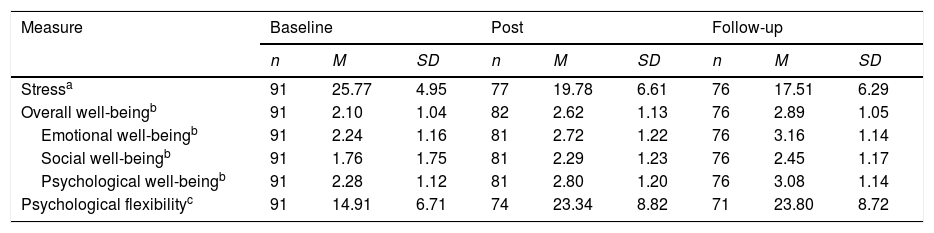

ResultsDescriptive statisticsDescriptive statistics of all measures involved in the analyses at preintervention, postintervention, and follow-up are shown in Table 1. Well-being and PF increased over time while stress decreased.

Descriptive statistics of measures of well-being and psychological flexibility.

| Measure | Baseline | Post | Follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| Stressa | 91 | 25.77 | 4.95 | 77 | 19.78 | 6.61 | 76 | 17.51 | 6.29 |

| Overall well-beingb | 91 | 2.10 | 1.04 | 82 | 2.62 | 1.13 | 76 | 2.89 | 1.05 |

| Emotional well-beingb | 91 | 2.24 | 1.16 | 81 | 2.72 | 1.22 | 76 | 3.16 | 1.14 |

| Social well-beingb | 91 | 1.76 | 1.75 | 81 | 2.29 | 1.23 | 76 | 2.45 | 1.17 |

| Psychological well-beingb | 91 | 2.28 | 1.12 | 81 | 2.80 | 1.20 | 76 | 3.08 | 1.14 |

| Psychological flexibilityc | 91 | 14.91 | 6.71 | 74 | 23.34 | 8.82 | 71 | 23.80 | 8.72 |

Participants were largely female (72%), with an average age of 42.4 years (SD=9.6) and ranging from 23-60 years. Participants were all Caucasian with the vast majority being German (97%), and the remaining Austrian and Hungarian. The social class distribution was as follows: 6.6% originated from the lowest, 30.8 from the lower middle, 56% from the middle and 6.6% from the upper middle social class. Further, 67% of the participants had an upper secondary education, 27.5% a higher education, 3.3% an other education while 2.2% had no education.

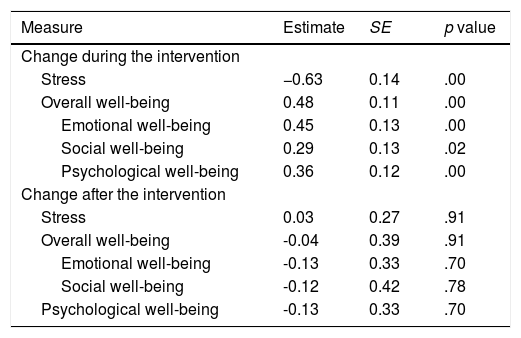

Is an increase in PF associated with a decrease in stress and an increase in well-being?During the intervention. LGMs indicated that an increase in PF during the intervention was significantly negatively related to a decrease in stress and positively related to an increase in overall well-being as well as all three of its components: emotional, social, and psychological well-being during the intervention (Table 2). Estimates were highest for the association of PF with stress and overall well-being. Of the well-being subscales, emotional and psychological well-being resulted in higher estimates compared to social well-being.

Association between an increase in psychological flexibility during the intervention and changes in stress and well-being during or after the intervention.

| Measure | Estimate | SE | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change during the intervention | |||

| Stress | −0.63 | 0.14 | .00 |

| Overall well-being | 0.48 | 0.11 | .00 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.45 | 0.13 | .00 |

| Social well-being | 0.29 | 0.13 | .02 |

| Psychological well-being | 0.36 | 0.12 | .00 |

| Change after the intervention | |||

| Stress | 0.03 | 0.27 | .91 |

| Overall well-being | -0.04 | 0.39 | .91 |

| Emotional well-being | -0.13 | 0.33 | .70 |

| Social well-being | -0.12 | 0.42 | .78 |

| Psychological well-being | -0.13 | 0.33 | .70 |

Note. Reported estimates are based on standardized values.

After the intervention. An increase in PF during the intervention was not significantly associated with a decrease in stress and increase in well-being including all three subcomponents (emotional, social and psychological well-being) after the intervention (Table 2). Estimates for the association of PF with stress and overall well-being, including the subscales, were very small. As sex and age are not associated with both predictor (PF) and outcome (stress/well-being), the analyses were not controlled for sex and age (Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001).

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to investigate the association of an increase in PF with stress and well-being for individuals with at least a moderate level of stress. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine whether an increase in PF during an intervention is related to decreases in stress and increases in well-being after the intervention. As hypothesized, we found that a total increase in PF during the intervention was related to a decrease in stress and an increase in well-being during the intervention, but not after the intervention. These findings are in line with earlier research in the treatment of stress among social workers (Brinkborg et al., 2011), which found that changes in PF during an intervention were linked with decreases in stress during the intervention. Prolonged high levels of stress typically involve serious disruptions in daily life, and studies have suggested that ACT alters responses to stress in a way that leads to a reduction of stress (Bond & Bunce, 2003; Frögéli, Djordjevic, Rudman, & Livheim, 2016; Lloyd, Bond, & Flaxman, 2013). A group intervention study of individuals with psychological distress found that increases in PF during the intervention were related to increased well-being at postintervention (Fledderus et al., 2010). Our findings indicate that individuals with symptoms of stress benefit from a structured self-help intervention such as ours, which promoted changes in PF.

Well-being has crucial implications for the individual, society, and the economy and importantly, our findings imply that PF is linked to well-being. Evidence suggests that well-being is clearly connected to health care utilization, psychosocial adaptation and functioning, and work productivity (Chida & Steptoe, 2008; Keyes, 2004; Keyes & Grzywacz, 2005) and that ACT interventions are positively related to enhanced well-being (Bohlmeijer et al., 2015; Fledderus et al., 2010; Livheim et al., 2014; Räsänen, Lappalainen, Muotka, Tolvanen, & Lappalainen, 2016).

A total increase in PF during the intervention was not associated with decreases in stress and increases in well-being after the intervention. Thus, people's increase in PF during the intervention was not related to their decreases in stress and increases in well-being after the intervention. This is partly opposed to earlier findings (e.g., Fledderus et al., 2010), that found increases of PF during the intervention (i.e. baseline to post treatment) were linked to improved well-being at follow-up. One study (Brinkborg et al., 2011) has examined the relationship between PF and improvements in stress and well-being during the intervention. To our knowledge, however, it has not previously been tested whether increases in PF during the intervention are linked to decreases in stress and increases in well-being after the intervention. Hence, our findings extend earlier research.

This study needs to be interpreted with several limitations taken into account. First, this study relied on self-reported measurements. These are prone to biases inherent in this assessment approach. Analyses of information stemming from other sources (e.g., experience sampling, friends and family or employers) may have resulted in different findings as self-report measures may not capture stress and well-being in their full complexity. A combination of self-report measures with physiological measures may deliver further insights. Second, the study sample was limited to individuals with symptoms of moderate to elevated levels of stress from the general population. Therefore findings cannot be extrapolated to individuals of low or (very) high stress. Third, participants were recruited through a newsletter of a health insurance company, which may have led to selection bias. Thus, participants were likely motivated and believed in the treatment approach as well its efficacy. Nevertheless, recruiting with the newsletter of the health insurance company is at the same time a strength as it allowed to sample nationwide. This is unique in a study in individuals with elevated levels of stress and more representative of the general population than recruiting in one particular company. However, identity of the participants was not revealed to the health insurance company. It may be possible that individuals are less willing to read a self-help book or may react differently if offered, for instance, by the employer. Further, it remains unknown whether the change process in PF with stress and well-being are similar in clinical populations, for example. As this is the first time that bivariate analyses of PF with stress and well-being were executed based on a self-help intervention, we cannot draw any conclusion whether strengths of associations are different in face-to-face therapy or guided self-help.

These limitations notwithstanding, our study shows that individuals with elevated stress levels at baseline reported an increase in PF, which was associated with a decrease in stress and an increase in well-being during an ACT intervention. Further, our results are of clinical importance, as self-help interventions are easily accessible, inexpensive (Ebert et al., 2016; Marks & Cavanagh, 2009), and can evidently promote crucial processes of change in stress and well-being. Further strengths of the study are the sample of individuals with heterogeneous occupations and that it is interconnected with studies designed to examine PF across different levels of analysis, including genetic research, in which PF has been linked with genetic polymorphisms (Gloster, Gerlach, et al., 2015). We have extended the existing body of literature by explicitly investigating the link between changes in PF, stress, and well-being and thus integrating research on PF, stress, and well-being.

More research on the temporal relationship between PF and stress and well-being is certainly needed. Future research should investigate if the association of changes between PF and stress and well-being is different in face to face therapy or guided self-help. Future work should also, for instance, extend the number of measurements of the outcome (e.g., after each week or session). This would enable a more fine-grained analysis of when relevant changes occur and how these changes are associated with each other. This is important as the reduction of stress and promotion of well-being could help deter more serious problems from developing. Our longitudinal analysis emphasized the potential of PF in promoting well-being and creating substantial changes in participants’ lives and thus provides support for the theory that PF and well-being are strongly linked (Ciarrochi & Kashdan, 2013; Hayes, 2013).

FundingThe work was supported in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation (FNSNF) under Grant no. 100014_149524/1 & PP00P1_163716/1.