We propose that social entrepreneurs may act as altruistic brokers helping their beneficiaries patch the structural holes that separate the disenfranchised and marginalized individuals and groups from the opportunities, resources, and capabilities available to more privileged actors. We test our model on a database of social entrepreneurs that received funding from the Schwab Foundation and Ashoka. Our case analysis and frequency analysis performed in NVivo shows that social entrepreneurs’ institutional work comprises: (1) bridging: helping beneficiaries gain access to resources and opportunities; (2) enabling: helping beneficiaries develop capabilities; and (3) bonding: helping beneficiaries form cohesive networks. Furthermore, some of these key types of institutional work may take the lead depending on various contextual factors so that either bridging, enabling, or bonding may become dominant.

Research on social innovation is fragmented, disconnected, and scattered among different fields, such as urban and regional development, public policy, management, social psychology and social entrepreneurship (Cajaiba-Santana, 2014). However, the common denominator in these sundry studies conducted in different fields is the focus on social innovation as a way to address the deep-seated societal challenges that encompass social and economic inequality, marginalization, perilous climate change or healthcare needs of people with no health insurance or money to pay for medical services.

Hence, researchers approach social innovation as an attempt to resolve some urgent social problems through the introduction of new and fair products and services. It is “a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than existing solutions and for which the value created accrues primarily to society as a whole rather than private individuals” (Phills, Deiglmeier, & Miller, 2008: 36). Social innovation is focused on bringing about beneficial social impact (Goldsby, Kuratko, Bishop, Kreiser, & Hornsby, 2018). It is “explicitly aiming at the creation of social value and thus at positive social change” (Choi & Majumdar, 2014: 27). Yet scholars also study social innovation as a species of entrepreneurship and examine it in light of such concepts as entrepreneurial process; opportunity recognition; network embeddedness; financial risk and profit; the role of individual vs. collective action in managing and structuring enterprises; creativity and innovation (Shaw & Carter, 2007).

In this paper, we contribute to research on social innovation by developing and testing a model of social entrepreneurs as altruistic brokers. Based on institutional theory, prior studies have developed an idea that social entrepreneurs may seek to fill institutional voids. This means that social entrepreneurs strive to develop innovative substitutes or complements for weak or absent institutions. For example, in some countries institutional voids block access of the disenfranchised groups, such as women, to markets (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Webb, Tihanyi, Ireland, & Sirmon, 2009; Mair, Battilana, & Cardenas, 2012; Mair, Marti, & Ventresca, 2012). Advancing this line of research, we propose here that institutional voids represent structural holes (1997, Burt, 1992; 2002) of a special kind. Structural holes are defined in network theory as missing links in the network that allow well-connected actors serving as brokers to connect otherwise disconnected actors, and consequently, receive some benefits for providing such intermediation services (Burt, 1992). Developing this theory, we propose that structural holes can separate actors not only from other actors but also from the opportunities, resources and capabilities required for engagement in productive activities. From this standpoint, institutional voids can be regarded as structural holes of a special kind whereas social innovators can be seen as altruistic brokers rather than brokers driven by self-interest that help the disenfranchised individuals and groups to patch institutional voids.

Social innovation may be urgently needed because the existing institutions are weak or ineffective thus leading to the emergence of institutional voids that may disenfranchise marginalized actors (Mair et al., 2012a, 2012b). Furthermore, social innovation represents a special kind of institutional work that involves removal or transformation of existing institutions and/or creation of new institutions (Oeij, van der Torre, Vaas, & Dhondt, 2019; Seelos & Mair, 2016). Social innovators utilize different strategies, such as scaffolding, to radically transform the existing institutions and to effectively create new institutions. They may achieve these goals by: (1) mobilizing resources including institutional resources, social and organizational resources and material or financial resources; (2) changing the existing patterns of behavior; and (3) concealing the long-standing goals (e.g., women empowerment) by referring to uncontested goals (e.g., getting clean water to all the villagers) (Mair, Wolf, & Seelos, 2016).

Advancing the theory of social innovation strategy, we propose that social innovators may seek to connect the disenfranchised individuals and groups to the previously unavailable or inaccessible resources, capabilities, and opportunities. In so doing, social innovators could make the entire social system more effective by improving its connectivity, inclusiveness, and fairness (Liguori, Bendickson, & McDowell, 2018). Specifically, social innovators’ institutional work (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006) may encompass: (1) bridging, i.e., helping the disenfranchised individuals and groups to obtain resources and explore opportunities that used to be out of their reach; (2) enabling: helping the disenfranchised individuals and groups to acquire capabilities they need for obtaining and utilizing resources and pursuing opportunities; and (3) bonding: helping the disenfranchised individuals and groups form cohesive networks of mutual support to increase their access to opportunities, ability to share resources and enhancing their collective power, e.g., bargaining power.

To test the proposed model of social innovation as altruistic intermediation, we examine the Schwab Foundation’s database of social ventures that have received their funding complemented by similar data (e.g., provided by the Ashoka Foundation). Our frequency analysis of the keywords specified based on the proposed theoretical model and subsequent case analysis shows that all the three brokerage roles are typically performed by social innovators as part of their role of altruistic brokers. However, our examination also demonstrates that bridging, enabling and bonding can be connected in a different way depending on various contextual factors.

Specifically, we discover that when the beneficiaries are known and already involved in productive activities but act alone and are disconnected which makes them vulnerable, social innovators may lead with the bonding function. In fact, helping the beneficiaries to connect and form the networks of knowledge and mutual support becomes social innovators’ primary task. Subsequently, social innovators may use the alliances and networks they have put in place to help the beneficiaries develop new skills and capabilities. Therefore, the function of enabling is facilitated by bonding. Finally, social entrepreneurs may build on bonding and enabling to help the beneficiaries gain access to new or previously unavailable or inaccessible entrepreneurial opportunities. Thus, bonding and enabling increase their efficacy as they facilitate the function of bridging.

In contrast, when social entrepreneurs may initially need to identify their potential beneficiaries and determine what kinds of resources they need and/or what opportunities they may pursue. In this case, social innovators may begin with bridging or helping the beneficiaries to acquire resources. After connecting the beneficiaries and resources, social innovators may apply the strategy of enabling to help the beneficiaries develop capabilities that would allow them to utilize the resources they now have more effectively; pursue better opportunities and become more skilled at identifying and pursuing opportunities. Finally, social innovators apply bonding to help the beneficiaries share their knowledge and expertise and exercise their collective bargaining power.

Finally, there are situations when the beneficiaries and their needs are known, and the necessary resources are available to them. However, the beneficiaries may lack the capabilities so that they cannot utilize the resources or take advantage of opportunities quite effectively. In this case, social innovators may begin with enabling in order to help the beneficiaries to develop their capabilities. Subsequently, social innovators may use bonding to help the beneficiaries form networks of mutual support. Social innovators may then apply bridging to make the beneficiaries more adept at identifying and pursuing opportunities. The factors that determine how bridging, enabling and bonding can be applied are as follows: (1) beneficiaries’ access to resources; (2) beneficiaries’ capabilities or their level of development; (3) beneficiaries’ access to networks of learning, mutual support and collective power; and (4) beneficiaries’ ability to identify promising opportunities as well aw the ability to differentiate among opportunities, and pursue opportunities effectively.

This paper is organized as follows. First, we put forth a conception of social innovators as altruistic rather than selfish brokers. Second, we describe our methodology and results. Third, we analyze individual cases. Fourth, we discuss how our theoretical propositions were tested via analysis of the empirical data, and what insights about social innovation emerge from our research.

Theoretical frameworkA recent review of the social innovation literature has approached different studies of social innovation as focused on input, throughput or output (Lubberink, Blok, van Ophem, & Omta, 2017). Thus, papers delving into social innovation as input commonly examine how market failures and/or government failures to provide necessary products and services may trigger social innovation (Lubberink et al., 2017). From this perspective, social innovation is driven by some unmet needs whereas the social innovator or social entrepreneur acts as an agent of change assuming the responsibility for solving important societal problems that other parties either overlook or fail to address (Choi & Majumdar, 2014).

In contrast, studies approaching social innovation as throughput examine the actual process of social innovation. This research stream commonly addresses the topic of securing stakeholder involvement. Social innovators often seek to attract a wide range of stakeholders in order to better understand the social need or problem that ultimately should be met or solved via innovative approaches (Sharra & Nyssens, 2010). To be successful, social entrepreneurs also need to operate within some ‘community’ or ‘collective’ structures (Lettice & Parekh, 2010; Shaw & Carter, 2007). Another theme frequently examined in studies of social innovation is the level of formalization. Specifically, social innovation tends to be less formalized than other forms of innovation since social innovators continuously have to develop and adjust their innovations to the changing context and varying needs of their beneficiaries (Choi & Majumdar, 2014). In addition, prior research has established that social innovators utilize networks to build local credibility and support for their ventures (Shaw & Carter, 2007; Urbano, Toledano, & Soriano, 2010).

Finally, studies focused on the outcomes or output of social innovation seek to measure the extent to which social enterprises make up for the market and/or government failures and fulfil the unmet societal needs (Lubberink et al., 2017). This outcome perspective on social innovation subscribes to the Schumpeterian approach to innovation as a potential market transformation (van der Have & Rubalcaba, 2016). Unfortunately, measuring social innovation’s success is more difficult than evaluating commercial innovation’s success. While the latter is perceived as effective when it is profitable or fast-growing, social innovation is multifaceted, and therefore, can be useful in various ways (Kramer, 2005).

Importantly, social innovation has dramatically changed our lives. Thus, “thousands of recent examples of successful social innovations have moved from the margins to the mainstream. They include neighborhood nurseries and neighborhood wardens; Wikipedia and the Open University; holistic health care, and hospices; microcredit and consumer cooperatives; the fair-trade movement; zero-carbon housing developments and community wind farms; restorative justice and community courts; and online self-help health groups” (Mulgan, 2006: 145). At the same time, the terms innovation and social innovation are used sometimes too loosely as many organizations apply them to any product (Seelos & Mair, 2016). Hence, scholars rightly emphasize that social innovation represents an outcome of an innovation process and identify various pathologies of social innovation that may prevent it from generating a significant social impact, such as never getting started, stopping too early, stopping too late, pursuing too many bad ideas, scaling too little and innovating again too soon (Seelos & Mair, 2016).

Institutional theory suggests that social innovation represents institutional work, i.e., “the purposive action of individuals and organizations aimed at creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions” (Lawrence & Suddaby, 2006; Lawrence, Suddaby, & Leca, 2009: 2–3). At the same time, have described weak or absent institutions as institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, 1997). Such institutional voids especially affect certain disenfranchised groups, e.g., women living in the remote areas of Bangladesh (Mair et al., 2012a). Because of the existence of institutional voids that disconnect potential market actors from certain (or any) productive activities (Brenes, Ciravegna, & Pichardo, 2019; Mair et al., 2012a) institutional work becomes indispensable. Social innovators, or social entrepreneurs may seek to help the disenfranchised individuals or groups to cross or patch institutional voids (Mair et al., 2012a, 2012b).

Previous studies have defined institutional voids as “analytical spaces at the interface of several institutional spheres” (Mair et al., 2012a: 822). Such voids arise due to the contradiction and conflict between religious, political and community spheres (Mair et al., 2012a). Advancing this perspective, we propose that institutional voids may be regarded as structural holes (2002, Burt, 1997) of a special kind. Usually, structural holes are interpreted as missing links between network participants (Burt, 1992; Walker, Kogut, & Shan, 1997) that provide some information advantages to actors positioned as brokers that may use such advantages to extract rents from other, less connected, and therefore, less informed participants. Consequently, actors that create open networks facilitating exposure to different information flows can benefit from their network positioning compared to actors that create closed networks (Shipilov & Li, 2008).

In our view, structural holes may separate certain marginalized and disenfranchised actors (that may include individuals and groups or even entire nations or parts of the world) from opportunities, resources, and capabilities available to more privileged actors. Such privileged actors may enjoy enormous advantages thanks to their higher socio-economic status, wealth transferred from one generation to another, and social, political, and cultural embeddedness. For example, privileged actors may reap some benefits from being part of an ethnic or religious majority or having the citizenship rights and entitlements as opposed to merely the resident status. Thus, children coming from disenfranchised groups with low socio-economic status or belonging to certain racial, ethnic and religious groups or women may have insufficient access to education, advanced technologies, political and economic rights or capital (Peake, McDowell, Harris, & Davis, 2018). Disenfranchised individuals and groups may lack the resources (e.g., money or tools) and/or capabilities (e.g., the ability to conduct business analysis) because of their low level of education, social disembeddedness or lacking experience. Hence, social innovators may act as altruistic intermediaries or brokers to help their beneficiaries transgress and patch the structural holes that separate them from engaging in desired activities.

There is an ongoing debate in the literature as to the sources of advantage accruing to actors due to their social capital, i.e., a set of resources stemming from being connected to other actors (2000, Burt, 1992). Some scholars believe that such advantages accrue as a result of “bonding” with other actors via strong connections or cohesive ties that may result in network closure barring the uninitiated (Coleman, 1988). Other scholars propose that greatest advantages accrue to market actors due to their network positioning as brokers that “bridge” otherwise disconnected actors (2000, Burt, 1997). Being a broker allows to control information and share it with other market participants selectively depending on their contributions. This empowers brokers that could benefit financially from their network positioning (2000, Burt, 1997).

Subsequent research has revealed that both “bonding” (Coleman, 1988) and “bridging” (2000, Burt, 1997) may afford various advantages and disadvantages contingent on a variety of contextual factors. For example, in China, known for its collectivist values, brokers can benefit from connecting otherwise disconnected actors free of charge rather than seeking to exploit other market actors’ disconnectedness (Xiao & Tsui, 2007). Cohesive ties, though, hamper cooperation (Gargiulo & Benassi, 2000). Importantly, institutional environment (Batjargal, 2010) may affect the benefits and shortcomings of bonding vs. bridging. Although bonding and bridging are usually contrasted as the two opposite ways of positioning in a network (2000, Burt, 1997; Coleman, 1988), we propose that social innovators as altruistic intermediaries may utilize both strategies: (1) help disenfranchised actors gain access to the desired productive activities by connecting them to the requisite resources, capabilities and opportunities (in so doing, the social innovators would apply the bridging function) and (2) help the disenfranchised actors to form cohesive networks of mutual support and learning as well as exercising their collective bargaining power (in so doing, the social innovators would use the bonding function).

Furthermore, unlike previous researchers that regarded network connections as pre-existing (Coleman, 1988; Burt, 1992, 1997), we propose that social innovators may actively seek to connect with potential beneficiaries as well as to connect such beneficiaries, once they have been found. These potential beneficiaries may live in other countries or may belong to different racial, ethnic, religious, or socioeconomic groups. This may impede social innovators’ efforts to serve as brokers. And yet social innovators could deliberately search for potential beneficiaries (or find them accidentally), and then begin to connect such beneficiaries to each other so that they could form alliances.

Previous research has identified a number of strategies used by social innovators. First, social innovators may diagnose the problem using “diagnostic framing” (Cavotta, Ramus, & Vaccaro, 2015; Maguire & Hardy, 2006; Strang & Meyer, 1993). Second, social innovators may devise an alternative model that would help to solve the identified problem by applying “prognostic framing” Cavotta et al., 2015). Third, social innovators may use motivational framing in order to urge the beneficiaries to eliminate the existing institutions, to transform the existing institutions or to create completely new institutions (Cavotta et al., 2015).

Other strategies used by social innovators include: changing the lens, building missing links, engaging a new ‘customer’ base, and leveraging peer-support (Lettice & Parekh, 2010). Changing the lens means approaching the problem from a different perspective compared to other actors that could be conducive to finding a solution (Lettice & Parekh, 2010). Building the missing links refers to connecting previously unconnected parts of the market or better connecting the whole (Lettice & Parekh, 2010). Engaging a new customer base signifies targeting previously overlooked or neglected clients (Lettice & Parekh, 2010). Finally, leveraging peer support means building tightly-connected networks that could be used for inspiration, searching for new ideas, sharing knowledge and getting support (Lettice & Parekh, 2010).

Additionally, scholars have argued that social innovators use “scaffolding” to transform the existing institutions and create new institutions (Mair et al., 2012a, 2012b; Seelos & Mair, 2016). Scaffolding involves three operations: (1) mobilizing resources including institutional resources, social and organizational resources and material or financial resources; (2) stabilizing the ongoing transformation of the existing patterns of behavior; and (3) concealing the long-standing goals (e.g., women empowerment) by referring explicitly to uncontested goals (e.g., getting clean water to all the villagers) (Mair et al., 2016).

Building on prior research on social innovators’ strategies (Cavotta et al., 2015; Lettice & Parekh, 2010; Seelos & Mair, 2016), we propose that social innovators do their institutional work (i.e., eliminate or transform the existing institutions or create new institutions) by patching structural holes. This institutional work can start with bridging, that is, identifying beneficiaries separated from resources, capabilities and opportunities, establishing their deep-lying interests and connecting them to resources and opportunities they regard as desirable but unfortunately unavailable or inaccessible. Subsequently, social innovators can perform the role of enabling as they seek to empower the beneficiaries by helping them to obtain the needed capabilities that could allow initiating desired activities. Finally, social innovators could help their beneficiaries overcome various institutional barriers. For this, altruistic intermediaries may use bonding to help the beneficiaries form cohesive networks.

Overall, altruistic intermediaries are likely to play the three key roles: (1) help the previously disconnected actors to acquire lacking resources and pursue opportunities (“the bridging role”); (2) empower the previously disconnected actors by helping them to develop capabilities that would allow them to better utilize resources and explore, differentiate, select and exploit opportunities effectively (the enabling role”); and (3) connect the previously disconnected disenfranchised actors to one another so that they could form the cohesive networks of mutual support, learning and power (“the bonding role”). In the next section, we will explain how we have tested the proposed model of altruistic intermediation.

MethodWe used the database collected by the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship (Schwab, 2011). It represents a directory of social entrepreneurs that have received funding from the Schwab Foundation. For each venture, the following information is provided: name and photograph of the entrepreneur, the country of origin, website, followed by several paragraphs describing what the venture does, its focus (e.g., healthcare), geographic area of impact, model, number of direct beneficiaries, annual budget and percentage of earned income. In addition, there is a section offering a characterization of the social problem addressed by the venture and a section describing its innovation and activities. Yet another section is dedicated to the entrepreneur and concludes the conducted analysis.

Following prior research (Aron, Kayser, Liautaud, & Nowlan, 2009), we have also included into our dataset similar analyses of social ventures supported by Hystra and Ashoka. In total, 189 cases of social innovators from all over the world have been analysed in NVivo, the software for qualitative analysis of unstructured (Bazeley, 2007). We examined the sample to establish how social innovators used bridging, enabling and bonding for patching structural holes, and thus, connecting the beneficiaries to resources, capabilities and opportunities. Our first objective was to establish the purposes and sequence of these key activities performed by social innovators and their potential interactions.

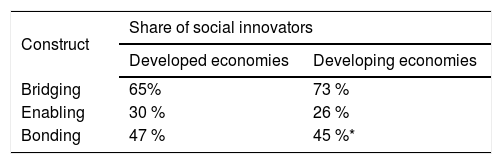

Our second goal was to examine the potential differences between social innovators from the developed and transition economies vs. developing economies. Following the United Nations’ country classification (UN, 2014), we divided the sample into the two subsamples. The first subsample comprises 140 social innovators operating in the developing economies. The second subsample comprises 49 social innovators from the developed and transition economies. To establish the relative frequency of bridging, enabling and bonding, we analysed the two subsamples using the “stem words”: “connect” and “resources” for bridging, “train” and “teach” for enabling and “link” and “overcome” for bonding.

The main method used in the paper can be described as abductive reasoning. As noted by Mitchell (2018):105), “a researcher may encounter an empirical phenomenon that cannot be explained by the existing range of theories. The researcher then seeks to choose the ‘best’ answer from among many alternatives in order to explain the ‘surprising facts’ or ‘puzzles’ identified at the start of the research process.” Abductive method allows to benefit from a combination of quantitative and qualitative method and using theory development as the basis for the subsequent mixed-methods examination. The initial theory development may help to create a model that can be tested both quantitatively and qualitatively. This makes abductive reasoning distinct from both quantitative analysis that begins with theory development and then proceeds to analyze the data to support or refute the theory and from qualitative analysis that begins with data analysis leading to further theory advancement.

Selection of the keywords used in the study was the result of an iterative, abductive process where the case material was scrutinized by all the authors in order to find the descriptions that were related the most to the overarching theme of how social entrepreneurs intermediate. Consequently, the selection of the keywords relied upon the cumulative insights derived from the exhaustive coding process. Furthermore, the coding was carried out as a manual process rather than an automated process. The reason for that was that we sought to better understand the context of each of the cases describing specific social ventures and individual entrepreneurs. Hence, the analysis of the material is supported by the NVivo software but the software is not used as a the tool of analysis (Gummeson, 2003). While computer-aided coding tools have their merits (and are becoming increasingly advanced), the manual coding approach was more aligned with the iterative, abductive method consistently utilized in the paper.

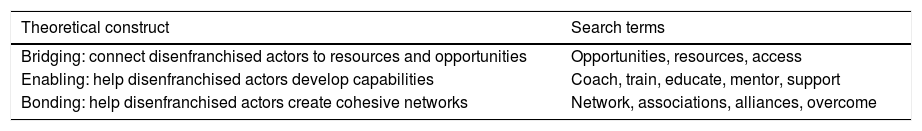

ResultsTable 1 presents our key terms and the stem words associated with each of these terms. Table 2 presents our frequency analysis conducted in NVivo. It shows that all the three principal activities characterizing social innovation as a certain type of institutional work (i.e., bridging vs. enabling vs. bonding) can be found in developed and transition economies and in developing economies. Although there are some differences between the two subsamples in terms of how frequently these three activities are utilized by social innovators, such differences are insignificant. Overall, all the activities were present.

The three functions of social innovators.

| Theoretical construct | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Bridging: connect disenfranchised actors to resources and opportunities | Opportunities, resources, access |

| Enabling: help disenfranchised actors develop capabilities | Coach, train, educate, mentor, support |

| Bonding: help disenfranchised actors create cohesive networks | Network, associations, alliances, overcome |

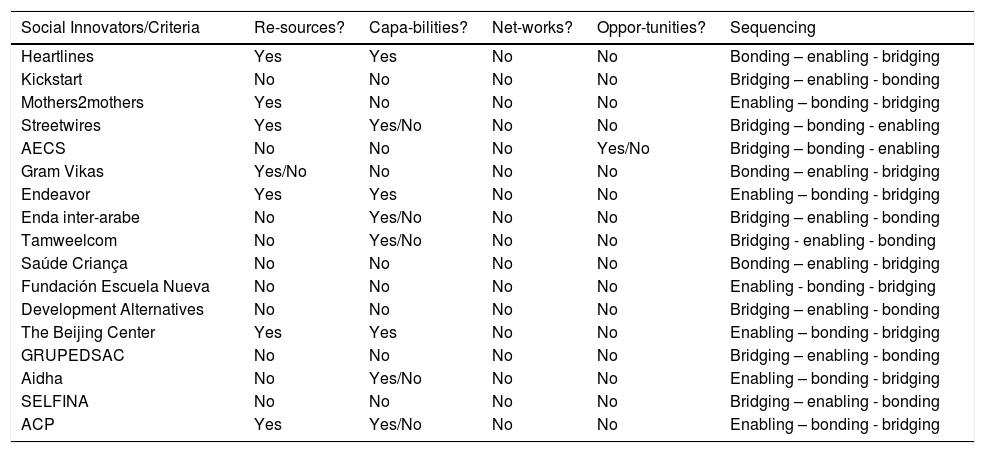

Our case analysis has established the existence of the three configurations of the core functions performed by social innovators. In the first configuration bonding prevails. The second configuration is determined by bridging. The third configuration is dominated by enabling. Other functions support the critical function and may merge so that, for instance, bonding and enabling could be difficult to distinguish at times. Furthermore, different branches of an organization could perform these specific functions.

Case AnalysisHeartlines created by the social entrepreneur Garth Japhet in South Africa began its intermediation activities with “setting up a web and cell phone-based social networking platform “forgood” that enables people to connect with each other based on location and interests in an effort to make a difference in their communities” (Schwab, 2011: 46). Applying the framework developed in this study, we characterize this creation of a social platform that facilitates building connections between the beneficiaries as bonding. Importantly, bonding also spearheaded enabling as the beneficiaries could easily find one another via the social platform and learn from each other so that they could develop new capabilities. In addition, bonding and enabling advanced bridging as previously disconnected actors who did not know about each other’s existence could inform each other about resources and opportunities.

Although it is clear that the functions of “bonding,” “bridging” and “enabling” are typically interwoven, it is important to realize that bonding in this case performs the key role triggering other functions. The fact that bonding is the starting point here could be explained by that the Heartlines did not need to identify its potential beneficiaries. Nor did it need to identify the problems they faced. Its key role was to connect the existing targets via bonding. Such bonding enabled the beneficiaries to develop new capabilities and connected them to other, previously disconnected actors facilitating alliance formation and search for opportunities. Thus, social-innovative organizations may commence with bonding when the beneficiaries are well-prepared but disconnected lacking a vehicle they could use for self-organizing. Consequently, the process of collective sensemaking can be initiated via bonding.

KickStart created in the US by Nick Moon and Martin Fischer but operating in Africa “trains private sector manufacturers to mass-produce tools, and uses innovative marketing techniques to sell it to entrepreneurs in poor communities through a network of local retail shops” (Schwab, 2011: 48). In essence, this social-innovative organization identifies and makes available to the beneficiaries a set of products that the beneficiaries actually need (but currently do not have). Ironically, the beneficiaries do not fully realize that they need these products and need to be convinced to buy them via creative marketing.

One can surmise that the local retail stores do not merely help entrepreneurs obtain the resources they need at a fair price but may also provide some training and advice (i.e., exercise enabling). Furthermore, entrepreneurs that meet in stores and participate in training can form knowledge networks, or bond. Apparently, in this case, bridging plays the critical role complemented by enabling and bonding. Since the beneficiaries are not yet well-prepared, bridging comes first so that the social-innovative organization plays the role of outside mediators that facilitates collective sensemaking (Strike & Rerup, 2016).

Mothers2mothers created in South Africa by the two Americans, Mitchell J. Besser and Gene Falk, “trains and employs new mothers with HIV to provide education and support to their peers, empowering them to access lifesaving treatment for their babies and themselves. Mothers2mothers identifies new HIV-positive women, puts them through a rigorous formal training program, and returns them to the clinics and maternity wards as paid Mentor Mothers. As mentors, they educate new mothers, supporting them daily…They also work alongside doctors and nurses, filling in service gaps by addressing the special needs of their HIV-positive clients.” (Schwab, 2011: 53). Therefore, mothers2mothers starts with enabling the disenfranchised actors that acquire the needed capabilities and subsequently provide support to new patients. Afterwards, mothers2mothers helps the selected actors that have been enabled to get a job helping others who are in the same boat: thus, bridging actors and resources. Finally, the venture creates networks of mutual support via bonding. In this case, enabling is the critical function as the beneficiaries need to be well educated, that is, acquire not only new skills but a different mindset as well so that they could initiate bridging and bonding working as intermediaries.

Streetwires is a social-innovative organization created by Patrick Schofield in South Africa. It connects unemployed young people to the valuable opportunity of working in the crafts industry. Adding to this bridging function, i.e., linking the disenfranchised actors to opportunities, and enabling function, i.e., teaching disenfranchised actors to work as artisans or even as true artists, Streetwires also gets engaged in bonding via the Indalo project. Specifically, “Streetwires regularly consults and assists other craft organizations as to how they can achieve their objectives. A parallel non-profit organization, Streetwires Training and Development, sets the company’s broader social and community development goals in terms of skills training, individual artist development and a series of outreach initiatives in orphanages, schools and impoverished communities.” (Schwab, 2011: 58). Thus, bonding becomes a separate function carried out by a branch of Streetwires. Moreover, bonding is used not only to help the disenfranchised actors to connect to opportunities but also to make the entire industry more interconnected.

Aravind Eye Care System (AECS) created by Thurasilaji Ravilla, is “recruiting and training hundreds of young rural women each year as eyecare technicians, thereby giving them a career opportunity and significantly reducing the cost of eyecare; and establishing a network of Vision Centers with low-cost telemedicine technology to provide primary eyecare to rural areas and thus enhancing access” (Schwab, 2011: 64). Thus, the AECS starts with the bridging strategy by identifying young women that could be trained as eyecare technicians and helping them to take advantage of this opportunity. This new, young and dedicated workforce is then enabled through intensive and ongoing professional training. Finally, a network of Vision Centers is put in place to perform the function of bonding. It allows creating an interconnected medical organization that has everything – from production of high-quality but low-cost lenses to rural medical facilities to hospitals with modern equipment and well-trained doctors to telemedicine spreading knowledge about cheap and widely available eyecare. Thus, bonding is reinforced via bridging, or viral marketing creating a dedicated client base. Bridging is dominant here, both for connecting talented people and jobs, and connecting clients in need with high-quality but affordable products and services. However, bonding is critical for the purposes of creating a diversified professional organization with high connectivity and business efficacy.

Gram Vikas “through its Movement and Action Network for Transformation in Rural Areas (MANTRA), has helped more than 48,107 families in 787 villages build low-cost facilities for safe drinking water and proper sanitation” (Schwab, 2011: 79). In this case, the social-innovative organization begins with bonding. It recruits a sufficient number of villagers that could take advantage of enabling, that is, learning low-cost (but not costless!) methods of helping themselves. Once bonding is accomplished, enabling takes place as the beneficiaries are taught the appropriate techniques, finally, bridging occurs as the beneficiaries assembled into network are being connected with the desired opportunities. Unlike Heartlines, bonding is dominant here not because the beneficiaries are ready but precisely because initial self-organizing into associations and networks is imperative for enabling and bridging. Bonding leads to greater connectivity and efficacy as it helps the beneficiaries to professionalize.

Endeavor created by Linda Rottenberg from the US operates on the three continents. It has the three principal objectives: 1) unleash untapped, high-potential entrepreneurial talent and stimulate new venture creation in a country (enabling); 2) help create a venture-friendly environment where entrepreneurs can access the knowledge, networks and capital they need to succeed (bonding); and 3) widen economic participation and opportunity by elevating entrepreneurs to become national role models, inspiring emerging market citizens, particularly youth, to take risks and turn their ideas into reality (bridging). Endeavor strives to generate awareness among potential beneficiaries about entrepreneurship. Bonding, or creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem, is Endeavor’s key activity that allows ramping up small ventures. In turn, bonding facilitates bridging and enabling. Bonding is the critical function here because it makes it possible to exercise both bridging and enabling more effectively. Creation of a venture ecosystem in the country increases overall connectivity facilitating entrepreneurship.

Enda inter-arabe (operating in Tunisia) and created by Essma Ben Hamida, a Tunisian native, provides lines of credit with customer service to underserved customers. Its goal is to overcome the dependence mentality among the social innovators. Along with its business products and agricultural loans, Enda inter-arabe provides specialized products such as education and home improvement loans. Although its main goal is bridging, that is, connecting potential entrepreneurs to financial resources, Enda inter-arabe also facilitates both enabling and bonding as it provides business development services and hosts discussion groups. Bridging is the critical function because the beneficiaries do not have the means to pursue opportunities they already have identified. However, enabling and bonding are important, too, as they help the beneficiaries to identify a greater variety of opportunities and ways of pursuing them. This increases the professionalism of the beneficiaries and creates an interconnected community.

Tamweelcom created by Ziad Al Refi and operating in Jordan is a one of the largest microfinance organizations in this part of the world. It has developed a range of financial, insurance and non-financial services for women-led families and widows in the poorest communities. Tamweelcom is essentially engaged in bridging but it also focuses heavily on bonding and enabling through its business training and vocational services programs. For example, it offers group loans to women to connect them to resources. Thus, both bonding and enabling complement and enhance bridging.

Saúde Criança founded by Vera R.G. Cordeiro from Brazil commenced with bonding by creating a network of volunteers providing post-hospitalization assistance to poor families with children recently discharged from the hospital. Via enabling, Saúde Criança makes it possible for parents of children helped by volunteers to provide a treatment that takes into account the full range of economic and social causes of the illness. Saúde Criança “gives nutritional advice, delivers medicines, offers psychological counselling, vocational training, and housing improvements to ensure adequate living conditions” (Schwab, 2011: 157). Thus, bonding and enabling facilitate bridging of poor families and opportunities to improve healthcare and living conditions for the disenfranchised families. Importantly, bonding is critical as it creates a volunteer-parent network that facilitates enabling and bridging.

Fundación Escuela Nueva in Columbia created by Vicky Colbert (a native of Columbia educated in the US) also places an emphasis on bonding that is closely connected with enabling as the socially-innovative organization puts children into small study groups and “promotes active, participatory and cooperative learning” (Schwab, 2011: 173). Bonding also enhances enabling in a different way as Escuela Nueva uses teachers in the role of facilitators helping children “learn to learn” at their own pace. One of the key ideas behind this social innovation is to arrange effective bridging via the flagship community-building event. This is a global congress that brings together practitioners and policy-makers from around the world to learn and promote the model. Hence, bonding and bridging merge.

Development Alternatives created by Ashok Khosla in India has two principal goals: to produce income for the poor and to regenerate the environment. It begins with bridging by providing the needed resources, such as roofing systems, compressed earth blocks, fired bricks, recycled paper, handloom textiles, cooking stoves, briquette presses and biomass-based electricity to the poor. Enabling is combined with bonding as farmers learn critical agricultural information through volunteers. Therefore, without enabling and bonding increasing competence as well as connectivity, bridging would be ineffective.

The Beijing Cultural Development Center for Rural Women offers grassroots training projects focused on citizenship, gender, social responsibility, legal and political participation, economic independence and practical skills. The Center helps women from poor families to learn some practical skills, which could ultimately help improve their social and economic development. Hence, the Center focuses on enabling, i.e., coaching and training. However, active interaction with the instructors facilitates both bonding and bridging as women learn collectively to assess the merits and shortcomings of their venture prototypes. The emphasis on enabling is understandable given beneficiaries’ low level of preparedness. However, enabling is facilitated by active bonding that ultimately leads to effective bridging.

GRUPEDSAC started by Margarita Barney (a native of Mexico) is teaching sustainable solutions targeting low-income communities in rural areas of Mexico and other countries of Latin America. It focuses on “organic farming, rainwater harvesting, ecological construction, and solar and wind energy. All technologies are adapted to the respective environment and make sustainable use of the existing natural resources” (Schwab, 2011: 179). The emphasis is on bridging communities and opportunities via enabling. However, bonding also plays an important role as the organization creates Centers of Learning. Bridging is key as the goal is to connect the beneficiaries to opportunities. However, enabling and bonding lead to bridging since the targets lack both requisite resources and capabilities.

Aidha created by Sarah Mavrinac, a French national, is operating in many Asian countries (Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Myanmar, United Arab Emirates) and offers an array of services including money management, confidence-building, computing and entrepreneurship courses specifically designed for low-income workers from the developing world. Its teaching methodologies stress small group interactions, peer support and practical training. In other words, this socially innovative organization merges bonding and enabling. All courses are supported by supplemental coaching and business practicum experiences. These facilitate bridging as they allow the students to apply their nascent business and financial skills in a real business setting. Bridging represents Aidha’s far-reaching objective that is accomplished, however, by combining enabling and bonding.

SELFINA created by Victoria Kisyombe, a native of Tanzania, has addressed a certain structural hole: local customs and traditions make it difficult for women to own land and assets in Tanzania. It uses micro-leasing as an effective and practical way to provide credit exclusively to women entrepreneurs. Thus, SELFINA starts with bridging by connecting women to otherwise unavailable opportunities. At the same time, SELFINA applies enabling to turn women into owners instead of asking them for upfront investment in working capital and uses bonding to set up knowledge networks.

Association of Craft Producers (ACP) created by Meera Bhattarai, a native of Nepal, is “not just a cooperative; it is a catalyst for women’s empowerment by providing women craft workers with fair-income earning opportunities” (Schwab, 2011: 65). ACP focuses on enabling by teaching its beneficiaries how to produce high-quality products meeting world standards. Enabling is also used to raise women’s awareness turning the employees into a powerful force in their families and communities where they assume a more important role by virtue of becoming a top earner. Bonding is used to connect women sharing their experiences as their re-emergence as leaders may cause family conflicts. Finally, bridging is applied to find the best opportunities for selling the products at the best price. Enabling is the critical function used by this socially innovative organization because it ensures that the beneficiaries’ products are competitive whereas bonding contributes to social transformation and bridging helps to pursue entrepreneurial opportunities. Table 3 provides a summary of the analysed cases.

Summary of analyzed cases.

| Social Innovators/Criteria | Re-sources? | Capa-bilities? | Net-works? | Oppor-tunities? | Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heartlines | Yes | Yes | No | No | Bonding – enabling - bridging |

| Kickstart | No | No | No | No | Bridging – enabling - bonding |

| Mothers2mothers | Yes | No | No | No | Enabling – bonding - bridging |

| Streetwires | Yes | Yes/No | No | No | Bridging – bonding - enabling |

| AECS | No | No | No | Yes/No | Bridging – bonding - enabling |

| Gram Vikas | Yes/No | No | No | No | Bonding – enabling - bridging |

| Endeavor | Yes | Yes | No | No | Enabling – bonding - bridging |

| Enda inter-arabe | No | Yes/No | No | No | Bridging – enabling - bonding |

| Tamweelcom | No | Yes/No | No | No | Bridging - enabling - bonding |

| Saúde Criança | No | No | No | No | Bonding – enabling - bridging |

| Fundación Escuela Nueva | No | No | No | No | Enabling - bonding - bridging |

| Development Alternatives | No | No | No | No | Bridging – enabling - bonding |

| The Beijing Center | Yes | Yes | No | No | Enabling – bonding - bridging |

| GRUPEDSAC | No | No | No | No | Bridging – enabling - bonding |

| Aidha | No | Yes/No | No | No | Enabling – bonding - bridging |

| SELFINA | No | No | No | No | Bridging – enabling - bonding |

| ACP | Yes | Yes/No | No | No | Enabling – bonding - bridging |

Rethinking the roles of social innovators, we approach them as altruistic intermediaries that help the previously disconnected, disenfranchised and marginalized beneficiaries to acquire resources, develop capabilities and pursue opportunities On the one hand, social innovators act as brokers that help the disenfranchised actors to gain access to resources, capabilities and opportunities available for privileged actors. In effect, the beneficiaries may get engaged in productive activities or become more competitive and be able to reap some additional benefits for themselves, their families, and communities. On the other hand, social innovators do not seek to enrich themselves, but merely serve the beneficiaries. Hence, social innovators can be described as altruistic brokers or emerging leaders that help society to patch its institutional voids we define as structural holes (Burt, 1992, 2000) of a special kind separating disenfranchised actors from the desired resources, capabilities, and opportunities.

Overall, we approach society as a network of resources, capabilities, and opportunities in which the disenfranchised actors (individuals and/or groups) either lack access or have insufficient access to various resources, capabilities, and opportunities. Hence, we agree with Lettice and Parekh (2010) that social innovators seek to build the missing links. We view, though, such missing links are structural holes. We define the first role of social innovators acting as altruistic intermediaries as bridging, that is, connecting disenfranchised actors to resources they need to begin productive activities or increase their competitiveness.

We define the second role of social innovators acting as altruistic intermediaries as enabling. It is not sufficient to connect the disenfranchised actors to resources. They need to be taught how to use them effectively. Finally, we define the third function of social innovators as bonding. Even though the disenfranchised actors may already be connected to resources and opportunities and acquire some of the needed capabilities, they may face various institutional obstacles and could benefit from setting up a marketplace of ideas and experience sharing, gain access to common supplies, marketing, logistics and other business functions and enjoy deeper social and business connections with similar actors. Social innovators use bonding to help the beneficiaries form networks of knowledge and collective power.

Our analysis of individual cases suggests, however, that social innovators may use the key strategies of bridging, enabling, and bonding in different ways depending on various contextual factors. Thus, social innovators are likely to emphasize bonding when the beneficiaries already have the resources and some capabilities but are disconnected, and hence, cannot take full advantage of productive activities. For example, Heartline helps the beneficiaries to self-organize and benefit from creating a cohesive network. In this case, disconnectedness is the key broken link that needs to be repaired (Lettice & Parekh, 2010).

In contrast, when beneficiaries lack absolutely everything or almost everything and are poorly prepared for initiating productive activities, bridging becomes the dominant strategy. Hence, social innovators need to provide the resources that would allow the beneficiaries to connect to opportunities. Bridging, however, is complemented by enabling and bonding. For example, Kickstart designs the tools that the beneficiaries could use, trains the private manufacturers, uses marketing to attract the beneficiaries, and then helps them form networks. Micro-finance institutions providing small loans to local entrepreneurs that are disenfranchised because of their race, gender, socio-economic status, or class (caste) also begin with bridging, that is, providing the resources. Such bridging, however, is accompanied by enabling and bonding. In this case, enabling and bonding help the beneficiaries increase their efficacy. This allows micro-finance institutions to safeguard their investment since better educated beneficiaries as well as beneficiaries organized into networks are less likely to fail. For example, Enda inter-arabe and Tamweelcom do not just give loans but provide customer training and organizing.

Finally, education-focused organizations, such as The Beijing Cultural Development Center for Rural Women typically emphasize enabling as the primary strategy. However, ultimately educational institutions seek to connect actors to opportunities so that they would be able to apply their enhanced capabilities. Furthermore, bonding of different kinds usually makes enabling more effective. Bonding also allows newly educated actors to connect both socially and professionally making them more effective. Thus, Endeavor starts with enabling as it helps aspiring entrepreneurs with mentoring, then uses bridging to connect them to resources, and finally, applies bonding to create a national venture ecosystem.

The contributions of this study are as follows. First, we have developed an approach toward institutional voids as structural holes of a special kind separating the targets from resources, capabilities and opportunities that can be useful for better understanding the entrepreneurial nature of social innovation. As social innovators connect disenfranchised individuals to resources, capabilities, and opportunities, they increase the fairness, interconnectivity, and overall efficacy of the underlying social system. Second, we show that social innovators represent altruistic intermediaries that seek to help the beneficiaries and society as a whole whereas the motive of personal gain is not something that inspires them. Third, we demonstrate that either of the three primary strategies of social innovation - bridging, enabling, or bonding – may play a dominant role, and form different constellations with the other two strategies.

As any study, this research has some limitations. First of all, the material we obtained from different sources is not very detailed. More thorough investigation of different social innovative ventures complemented by interviews with the founders and their employees may advance our understanding of the reasons why social innovators tend to apply a certain strategy or constellation of strategies. Second, there could be some additional factors affecting the shape of social innovation we have not considered. For example, many social innovations are initiated by the outsiders coming from other cultures than the one in which they choose to operate. A deeper understanding of the cultural roots of social ventures and their embeddedness in a certain tradition could improve analysis of social innovation.

The practical implications of this study are significant. Knowing that the primary strategies of social innovation include bridging, enabling and bonding that may form different constellations as either of the three strategies may become dominant depending on various contextual factors, social entrepreneurs could reexamine the strategies they are currently using in terms of their efficacy and make the adjustments that might be needed, accordingly. We also suggest that future research could investigate how the strategies of bridging, enabling and bonding can be implemented in particular cultural-geographic locations given the specific needs of the disenfranchised and marginalized beneficiary.