Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has significantly transformed corporate behavior in the energy sector by enhancing the capacity and efficiency of information transmission and big data analysis. However, there is still a limited understanding of how AI influences new market entry mode strategies in overseas energy investments. Drawing on information processing theory, we propose that firms with advanced AI technology exhibit superior data processing capabilities, which can help energy companies mitigate the uncertainties associated with entering a foreign market and encourage them to choose a wholly-owned entry mode. We further hypothesize that the state ownership of firms, the political affinity between home and host countries, and the risk preferences of firm executives serve as moderating factors. Using a sample of Chinese-listed multinational firms in the energy sector from 2010 to 2021, our empirical results strongly support these predictions. These findings contribute to the emerging and crucial literature on the impact of AI technology on firms’ overseas investment behavior, particularly in the energy sector.

When expanding overseas, firms should consider not only the location choice but also the entry mode of internationalization (Hutzschenreuter, Matt & Kleindienst, 2020). Entry mode is an important strategic decision in the international expansion process of multinational enterprises (MNEs) (Brouthers, 2013), which greatly influences firms’ internationalization behavior and performance (Cui & Jiang, 2009; Tihanyi, Griffith & Russell, 2005). Nonetheless, there is already a considerable amount of literature investigating the drivers of entry mode from different perspectives, such as institutional factors (Ang, Benischke & Doh, 2015; Hernández & Nieto, 2015), cultural distance (Chang, Kao, Kuo & Chiu, 2012; Tihanyi et al., 2005), and firm resources (Meyer, Wright & Pruthi, 2009).

The deep integration of digitalization with global business has also made the digitalization of MNEs a major trend in international business studies (Ghauri, Strange & Cooke, 2021; Luo, 2021). In this field, the study of the internationalization of born-digital firms has arisen with a focus on digital risks (Kim & Cavusgil, 2020; Luo, 2022; Monaghan, Tippmann, & Coviello, 2020). Meanwhile, there have been concerns about the use of digital technologies in MNEs, such as the applications of digitalization in areas such as the speed of firms’ internationalization (Deng, Zhu, Johanson & Hilmersson, 2022; Lee, Falahat & Sia, 2019), business models (Reim, Yli-Viitala, Arrasvuori & Parida, 2022), merge and acquisition (Wang, Yuan, Huang, Liu & Zhang, 2024), and global strategy (Meyer, Li & Brouthers, 2023). Previous studies have also analyzed the impact of digitization on firms’ choice of entry modes (Ekeledo & Sivakumar, 2004b; Hennart, 2022; Li, Zhang, Fan & Li, 2021).

However, current international business scholars have primarily focused on digitization as a collection of digital technologies, with little attention paid to the specific technologies that constitute digitization, which may have unique implications for organizations (Ahi, Sinkovics, Shildibekov, Sinkovics & Mehandjiev, 2022; Ciulli & Kolk, 2023). Specifically, artificial intelligence (AI) has the ability to process data, which can help organizations make better predictions and explore potential patterns (Alnsour, Johnson, Albizri & Harfouche, 2023; Bosma & van Witteloostuijn, 2024; Harfouche, Quinio & Bugiotti, 2023). Yet, knowledge about whether AI affects an organization's decision of entry mode is limited. This is surprising as AI is emerging as an important strategic resource in the international business arena, realizing value for MNEs (Ghauri et al., 2021).

To address this research gap, we focus on the impact of AI technology on the entry mode of MNEs into foreign markets. Using Chinese publicly listed MNEs in energy sector from 2010 to 2021 as the sample, our findings provide a sufficiently strong confirmation of the argument that AI technology can facilitate the entry of energy firms into foreign markets in a wholly-owned manner. Grounded in the information processing theory (Egelhoff, 1991), we argue that energy firms having higher levels of AI technology imply better information processing capabilities, which can be effective in anticipating and minimizing uncertainty situations faced by firms, especially when they enter the host countries. Reduced uncertainty leads to lower business risks and increased viability for firms in foreign markets, resulting in greater confidence and advantage in choosing the wholly-owned mode. In addition, since the internationalization of energy firms will influence the profit and strategic security of the host countries, we argue that the different political affinity and the corporate state ownership can moderate the linear relationship between the level of AI technology and foreign market entry mode in different ways. Finally, since firm executives can significantly impact firm strategies, we also propose the moderating role of the risk preferences of firm executives.

We focus on the energy sector in China because China has become one of the most important global energy consumers, but more than half of its energy demand must be supplied from abroad. In addition, Chinese energy firms have invested extensively abroad, and the government has established internationalized energy cooperation mechanisms. Thus, Chinese energy firms have manifested a globalized layout, and their foreign market entry mode has general theoretical and practical implications.

Our study contributes significantly to the related literature. First, our investigation focuses on an important strategy of internationalization: entry mode. While there is prior literature on AI technology in MNEs, it mainly focuses on its impact on MNEs’ export, marketing, performance, and human resource management (Denicolai, Zucchella & Magnani, 2021; Hossain, Agnihotri, Rushan, Rahman & Sumi, 2022; Malik, De Silva, Budhwar & Srikanth, 2021; Yang, Lee & Chang, 2023). Second, we investigate a crucial component of digitization: AI technology. By delving into the AI module of digitization, we gained new insights into the role of digitization in developing internationalization strategies for MNEs. In addition, this study expands entry mode strategies in overseas investment in the energy industry from an information technology perspective, which specifically extends our understanding of the path of “how technology affects firms’ international entry mode by influencing knowledge processing.”

Theoretical backgroundArtificial intelligence and information processingAs a representative of the new generation of information technology, AI is receiving extensive attention from scholars and practitioners (Bosma & van Witteloostuijn, 2024; Collins, Dennehy, Conboy & Mikalef, 2021). AI is described as the use of theories, techniques, technologies, and application systems to replicate, enhance, and augment human intelligence (Rai, Constantinides & Sarker, 2019). Currently, MNEs are using AI more frequently to manage their operations and provide potential solutions (Luo & Zahra, 2023).

Specifically, AI technology can predict changes in international trade based on the information available, thus helping firms make better decisions (Rathje, Katila & Reineke, 2024; Yang et al., 2023). Machine learning skills in AI technology have aided banking organizations in detecting credit card fraud in the global financial sector (Chinn, Kaplan & Weinberg, 2014). In addition, AI technology can largely improve a firm's overseas sales performance. According to Denicolai et al. (2021)), AI technology can enhance firms’ understanding of foreign markets by utilizing data analytics to support their international marketing campaigns as well as remote contacts with local clients. In the global management of MNEs, human resource management (HRM) is a critical function (Cooke, Wu, Zhou, Zhong & Wang, 2018; Schuler, Dowling & De Cieri, 1993). AI technology in HRM boosts information flow and exchange, increases the return on investment in HRM, and provides a customized experience for employees (Malik et al., 2021; Malik, Budhwar, Patel & Srikanth, 2022; Vrontis et al., 2022).

According to information processing theory (Egelhoff, 1991), firms can be thought of as information processing systems with uncertainty work. In this situation, AI technology is crucial to address the uncertainty (Daft, 1992). On the one hand, AI technology is capable of identifying and analyzing risks on the basis of organizations processing information and providing organizations with decisions (conclusions based on algorithmic deliberation of available data) and solutions (alternative courses of action to solve issues) (Flasiński, 2016). On the other hand, AI technology is capable of analyzing and predicting known data and information and improving the organization's information processing capabilities to cope with internal complexity and environmental uncertainty.

Entry mode selection in response to new market uncertaintyModes of entry into foreign markets, which we call the entry mode in this study, seem to be the most popular directions for scholars to research international business (Werner, 2002). Entry mode is considered “a structural agreement that allows a firm to implement its product market strategy in a host country either by carrying out only the marketing operations (i.e., via export modes), or both production and marketing operations there by itself or in partnership with others (contractual modes, joint ventures, wholly owned operations)” (Sharma & Erramilli, 2004). Entry mode can be categorized as equity and non-equity, and these two types differ significantly in terms of investment requirements and control. Compared to non-equity mode (e.g., contractual modes such as licenses), equity mode (e.g., joint ventures and wholly-owned ventures) means that firms need to make greater investment commitments and gain a higher control level in the overseas business (Pan & Tse, 2000). This study focuses on the different entry modes between wholly owned subsidiaries and joint ventures. Both entry mode choices represent different risk-taking, commitments, and returns. Wholly owned subsidiaries enable multinational enterprises to maintain full ownership and control over their international operations, while the joint-venture type means that the firms need to cooperate with local firms and share the equity (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007; Slangen & Van Tulder, 2009). Since cooperation with local firms can take advantage of the local influence of the partner firm and its strengths in institutional legitimacy and information advantages, the uncertainty and risk faced by the joint venture will be reduced, and correspondingly, the returns received by the parent firm will also be reduced (Kim & Hwang, 1992).

When MNEs establish subsidiaries in a foreign country, they will face unknown situations and environmental uncertainty. From the transaction cost theory perspective, there are two different uncertainties. Internal uncertainty usually comes from the employees’ performance, while external uncertainty is always caused by the unpredictability of the host environment, such as the different policies or special laws (Brouthers & Hennart, 2007). Scholars have demonstrated that when foreign markets have high levels of uncertainty, parent firms should favor wholly-owned subsidiaries rather than joint ventures. The high level of equity can help subsidiaries protect proprietary advantages when they first build up in a new country, and then, they can communicate directly to reduce transaction costs. Therefore, firms can offset external uncertainty through integration decisions (Brouthers, 2013). Moreover, the different institutional environments are another important uncertainty factor influencing corporate strategic decision-making in new markets, especially the entry mode strategy. According to the institutional theory, firms must comply with the special rules to gain legitimacy from the local government (Gao & Hafsi, 2015). In other words, a stable and reasonable institutional environment means a good business environment, which will bring less political and legal uncertainty. Thus, MNEs will choose the joint venture mode to establish the subsidiaries because of the higher performance and the less risk.

MNEs expanding abroad must contend with a range of unknowns in the new market that limit their operations in the home market (Hill, 2008). Compared to domestic rivals, new foreign entrants face the “liability of foreignness” (LoF) in the host nation. This drawback results from the MNE's inexperience with the institutions, environment, and culture of the host market as well as from higher costs and discrimination (Eden & Miller, 2004). For MNEs, overcoming the LoF is an indispensable condition for firms to invest directly abroad (Barkema & Drogendijk, 2007). Therefore, when entering new markets, firms need an optimal market entry mode that can help them reduce uncertainty in unfamiliar environments and be able to fully utilize their superior capabilities (Chen, 2006).

Hypotheses developmentArtificial intelligence and entry mode selectionAs firms expand globally, leaders of MNEs face the challenge of managing complex operations across different regions and countries (Eden & Nielsen, 2020). MNEs have more complex internal systems and coordination with external stakeholders than domestic firms (Benito, Petersen & Welch, 2019). Meanwhile, MNEs may face intricate and unfamiliar external factors when conducting business abroad (Bhardwaj, Dietz & Beamish, 2007). For example, the diversity of foreign business environments, as well as the dynamic and unfamiliar nature of market environments, increase the uncertainty faced by firms, requiring firms to be able to analyze and process large amounts of information in a timely manner and to improve their information processing capabilities in order to support their decision-making process (Egelhoff, 1991; Kano, Tsang & Yeung, 2020).

AI is an emerging and highly effective technology for information and data processing (Bosma & van Witteloostuijn, 2024). It recognizes, learns, and processes external and internal information generated by organizations, helping firm managers make informed decisions and take appropriate actions (Ahmad et al., 2021). On one hand, AI technology can help firms process information more efficiently when entering foreign markets. This can aid in quickly understanding new markets, analyzing and predicting future market trends, and reducing the costs associated with familiarizing themselves with the environment. On the other hand, it can also get ahead of competitors and gain an advantage over its domestic counterparts when dealing with changing environmental conditions. Therefore, AI technology can assist firms in reducing environmental uncertainty, overcoming the LoF when entering the host markets, and enhancing their viability. In this case, firms are more likely to choose a wholly owned model of entry in order to maximize the return on investment within the ability to bear certain risks. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 1 Firms with high levels of AI technology tend to use wholly-owned entry mode to the foreign markets, while firms with low levels of AI technology tend to use joint venture entry mode.

The features of the institutional setting have a significant impact on the energy sector and the linked businesses. Energy is a critical resource for the country and is often influenced by national policies and political objectives, as noted by Frynas and Paulo (2007). State-owned enterprises (SOEs) may have different objectives than non-SOEs and may be seen as representatives of their home governments. State ownership may lead these firms to invest abroad more for political reasons than for economic gain Cuervo-Cazurra, Inkpen, Musacchio and Ramaswamy (2014). Meanwhile, China's pursuit of foreign energy sources has raised serious concerns in other countries. For instance, CNOOC (a Chinese state-owned firm) attempted the acquisition of Unocal (a US oil firm) in 2005, triggering significant political opposition in the United States, as the energy industry is a sensitive sector that has come under even more scrutiny, which the US government believes could undermine US national security and hurt vital energy supplies (Wan & Wong, 2009). As a result, state ownership may trigger legitimacy concerns of the host government and other stakeholders, raising political, national security, and economic concerns, as well as suspicions. This increases the political and social uncertainty that firms face in host countries and undermines the competitive advantage that AI creates for firms in host country markets.

While pursuing economic interests, SOEs also need to consider other non-economic factors, such as national strategic objectives and industrial policies (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2014). This may lead SOEs to weigh other non-economic factors in the decision-making process of the entry mode in addition to the market factors analyzed by AI. The influence of AI technology in the decision-making of SOEs is less weighted compared to that of non-SOEs, which reduces the impact of AI technology on firms’ choice of the wholly owned entry mode.

In addition, SOEs may face more constraints and complex decision-making processes (Budiman, Lin & Singham, 2009; Utoyo, Marimin & Murdanoto, 2019), which may reduce their ability to utilize AI technology to conduct market analysis and to respond rapidly to market changes. In contrast, non-SOEs typically have more flexible decision-making mechanisms and can make faster decisions based on AI analyses. As a result, the state-owned nature of firms may make them more cautious and reduce their preference for the wholly-owned entry mode. We therefore propose:

Hypothesis 2 State ownership weakens the positive relationship between firms’ AI technology and their wholly-owned entry mode to foreign markets.

When selecting an entry mode, firms must consider the particular characteristics of the host country (Shama, 1995; Tihanyi et al., 2005). In this context, firms should understand the host country's institutional environment and examine international agreements on bilateral politics, including political affinity considerations (Dixon & Moon, 1993; Li & Vashchilko, 2010).

A higher level of political affinity means that the firm comes from a country that shares more of the same national interests, which will lead to more support from the host country's stakeholders, and the firm's behavior in the host country is taken “for granted.” As Suchman (1995) points out, “taken for granted” is, without a doubt, the most subdued and potent source of legitimacy found. Firm behavior that is taken for granted is rarely subject to external intervention. Duanmu (2014) also shows that countries with closer political ties will gain more trust through past interactions in the bilateral context in which FDI behavior takes place. This will promote dialog and support between home and host governments to mitigate potential expropriation risks in the host country. When political affinity is low, the firm comes from a country with more diverse national interests, at which point host country stakeholders will have more significant security concerns about the energy firm. Firms’ access to information from the host country may be hindered by stakeholders such as the host government (Mariotti & Piscitello, 1995). This may increase the cost and difficulty for firms in obtaining information about the host country's market. On the contrary, higher political affinity implies a convergence of national interests and thus reduces the legitimacy problems faced by MNEs in the host country (Hasija, Liou & Ellstrand, 2020). When a high level of trust and goodwill exists between countries, firms face less pressure from regulatory systems, such as governments, which reduces the cost and difficulty of obtaining information, and firms are likely to have access to richer information than in countries with lower political affinity.

The analysis and prediction function of AI is based on the processing of historical data, and the more data there is, the more accurate the results will be. Thus, a high level of political affinity between the two countries enables firms to obtain more information quickly and easily, allowing AI technology to fully utilize its benefits while studying the host nation's market conditions. This can help firms quickly understand the market in the host nation, reduce uncertainty, and establish competitive advantages in the market.

Therefore, firms entering countries with high levels of political affinity will better enjoy various advantages and risk avoidance brought by AI technology and thus will be more inclined to select the wholly-owned entry mode. We hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 3 Political affinity strengthens the positive relationship between firms’ AI technology and their wholly-owned entry mode to the foreign markets.

In corporate governance, executives, as the managers of firms, often play major roles in strategic decision-making. However, according to Chiles and McMackin (1996)) and Brouthers and Brouthers (2003), managers might not be risk-neutral, and risk-averse managers might decide differently from risk-seeker managers. With the development of AI technology, corporate decision-makers are gradually noticing it as a powerful and advantageous information processing tool for decision-making and strategy formulation (Huo & Chaudhry, 2021; Rathje et al., 2024). When corporate executives have a higher risk appetite, they are more inclined to seek higher returns, meaning they will take higher risks associated with uncertainties in the host market. However, AI technology can analyze large amounts of historical data and provide in-depth market insights and forecasts, which can help executives understand the market conditions in the host country and identify market opportunities and risks, thus supporting executives in developing their strategies and increasing the chances of the firm's success in the host country.

When the executives’ acceptance of risk is high, the information support provided by AI technology reduces the uncertainty in the host market. This enhances the investment confidence of risk-averse executives who are more willing to take advantage of AI technology to pursue higher returns and greater market opportunities. Thus, based on the valuable information provided by AI technology, risk-averse executives are more inclined to select the wholly-owned entry mode in the decision-making process. This is because this decision means firms can implement their strategies flexibly and profitably. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 4 The executive risk preference strengthens the positive relationship between firms’ AI technology and their wholly-owned entry mode to foreign markets.

We constructed a dataset of MNEs in China's energy sector from 2010 to 2021 to test our hypotheses. China is one of the most important global energy consumers, relying on imports for more than half of its energy needs, and thus, Chinese energy firms are very active in outward foreign direct investment (OFDI). A sample of Chinese firms in the energy sector listed on both the Shenzhen stock exchanges and Shanghai stock exchanges was selected for analysis. This is due to the fact that listed firms, which are obligated by law to give correct information in their annual reports, have more dependable data on their operations abroad and sufficient resources for OFDI (Xia, Ma, Lu & Yiu, 2014). Therefore, the Chinese-listed firm in the energy sector provides an ideal setting in our study.

We collected data related to all parent firms and foreign subsidiaries from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database, which is a major source of data related to the Chinese listed firms (Wang & Qian, 2011). In this database, data on AI began to be available in 2010, so this year was the starting point of the sample. We focused on the foreign market entry mode of subsidiaries in this study, so we constructed subsidiary-year data as the basic independent observations, and the final sample contains a total of 654 foreign subsidiaries.

MeasurementDependent variableEntry mode. Following previous studies (Blomstermo, Deo Sharma & Sallis, 2006; Ekeledo & Sivakumar, 2004b), we used the share of equity in subsidiaries controlled by the parent firm as a measure of entry mode. We defined wholly-owned firms as those with corporate ownership shares above 95 percent equity and 10–95 percent ownership shares as joint ventures. Ownership shares below 10 percent are not included because these kinds of firms can be interpreted as portfolios rather than direct investments (Puck, Hödl, Filatotchev, Wolff & Bader, 2016). Specifically, we measured this variable as the dummy variable, valuing 1 for the entry mode of a wholly-owned subsidiary to enter a foreign market and 0 otherwise.

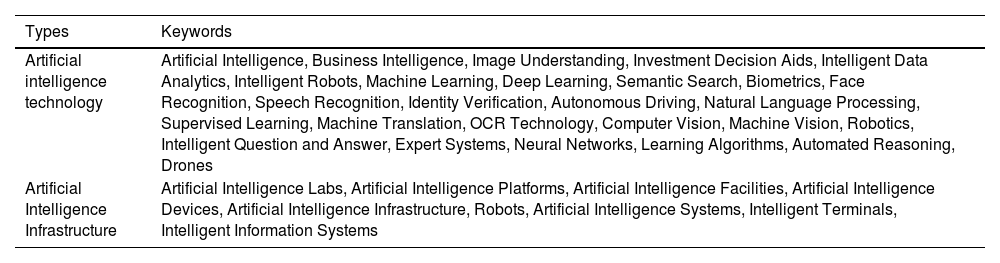

Independent variableAI technology was used as the independent variable. We followed the previous studies on firm's AI and used the number of word frequencies of keywords related to AI in the annual reports of listed firms as a proxy for the level of the firm's AI technology (Li et al., 2023a). We used the frequency of AI-related words for listed firms from the CSMAR database. The keyword collection was constructed from the perspectives of both AI technology and AI technology infrastructure to form a dictionary of keywords that can reflect the level of AI, with a total of 36 keywords. Table 1 represents the keywords dictionary used in the measurement. These data are obtained from annual reports using text mining methods, as annual reports reflect an organization's current state of business and corporate strategy. (Kloptchenko et al., 2004).

Keywords of the artificial intelligence.

State ownership. Due to the differences in the choice of entry mode between SOEs and non-SOEs (Grøgaard, Rygh & Benito, 2019), we followed the study of Duanmu (2014) and used the actual proportion of state-owned shares of the firm to measure the degree of state ownership of the parent firms.

Political affinity. Political relations between countries can influence firms’ strategic choices. We followed (Bertrand, Betschinger and Settles (2016) and Gartzke (1998) and measured it using the consistent voting behavior between the two countries in the United Nations General Assembly. We use a continuous variable valued between 0 and 1, a value of 1 represents completely consistent behavior of voting between the firm's home country and its target host country, and 0 representing opposite behavior of voting (Bertrand, Betschinger & Settles, 2016; Fieberg, Lopatta, Tammen & Tideman, 2021).

Risk preferences of executives. Due to the specificity of the Chinese capital market, the proportion of risky assets in individual assets is limited by the data acquisition and the small number of Chinese executives’ shareholdings, which is unsuitable for the Chinese context. We followed the method of Abdel-Khalik (2007) and Zhao, Niu and Chen (2022) to measure this variable by calculating a comprehensive index with multiple indicators. The ratio of risky assets to total assets, gearing ratio, core profitability ratio, retained earning rate, self-funding satisfaction rate, and capital expenditure rate are the six indicators we chose for this study to assess executives’ risk appetite. These indicators are drawn from the five aspects of asset structure, solvency, profit structure, profit distribution, and cash flow. Then, we calculated them using the principal component analysis method. The positive and larger values of executive risk appetite mean that executives are more inclined to take high risks, and negative and smaller values mean that executives are more risk-averse.

Control variablesWe also referred to a range of studies on entry mode, including different levels of variables to control for potential confounding effects (Hernández & Nieto, 2015; Kao & Kuo, 2017).

At the firm level, we first included Overseas experience, which is measured as the dummy variable, coded 1 if the executive team members have overseas study or tenure experience and 0 otherwise. Prior research has demonstrated that firms with executive teams possessing overseas experience are inclined to opt for wholly-owned subsidiaries (Nielsen & Nielsen, 2011). Subsequently, we accounted for firm size, which was quantified by the logarithm of a firm's annual total assets. Firm age is calculated by the number of years since its establishment. Larger firms with more extensive experience tend to possess greater knowledge of international operations and superior management capabilities (Jain, Thukral, & Paul, 2024). Debt ratio was utilized as a metric, expressed as the percentage of total liabilities to total assets, to mitigate the impact of capital structure on the decision-making for entry modes. We also used ROA to measure Financial performance.

At the country level, we included Turnover, measured as the dummy variable, coded as 1 if the host country leadership turnover occurs in the year of entry into the host country and 0 otherwise. Institutional distance has always been a major concern for international business scholars in studying the antecedents of entry mode (Ang et al., 2015; Brouthers, 2013). We measured it as the World Bank's Global Governance Index (Kogut and Singh (1988). Economic distance can influence the entry mode of MNEs (Tao, Zhanming & Xiaoguang, 2013), and we measured it by the logarithms of GDP per capita of the home country to each host country.

Estimation methodWe utilized a logistic regression model to examine the impact of AI technology on the likelihood that MNEs will choose a wholly owned subsidiary or joint venture, given that the dependent variable (Entry mode) is a dummy variable (López-Duarte & Vidal-Suárez, 2013). Specifically, the regression model was estimated as follows:

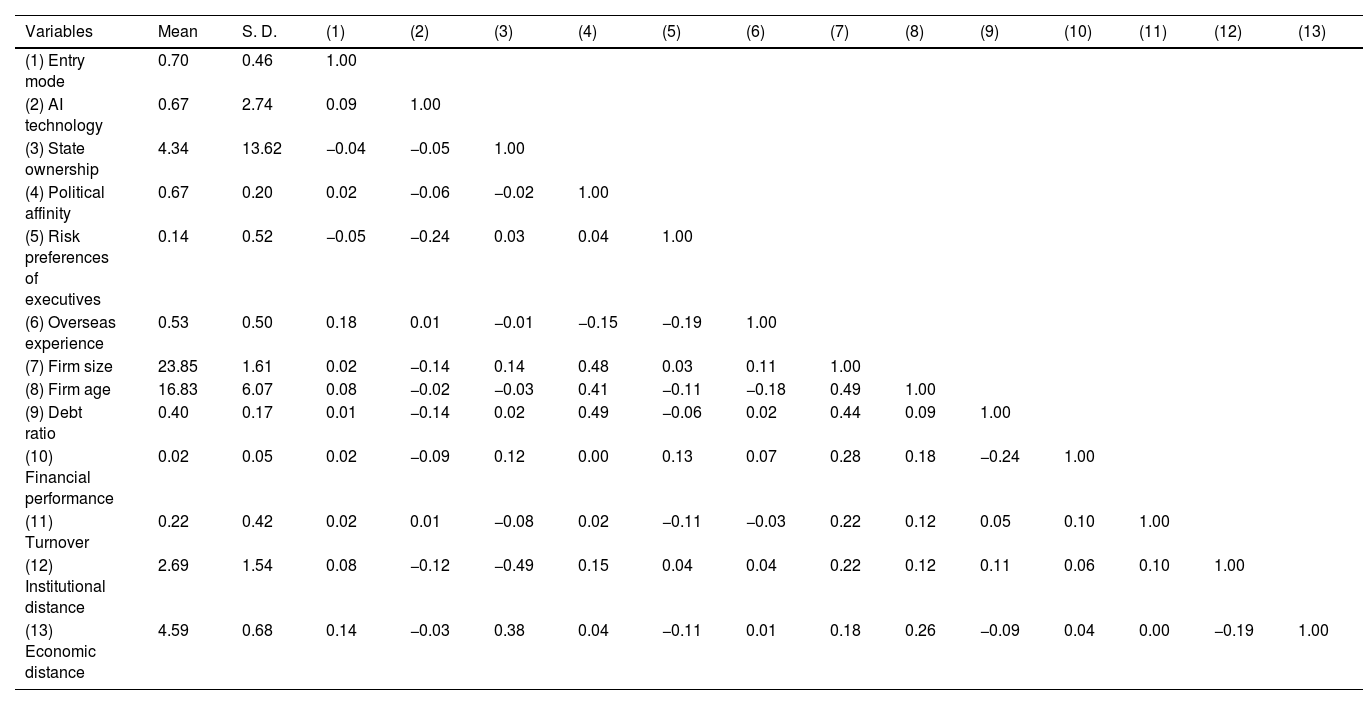

where β1 was used to test Hypothesis 1, and β5, β6, and β7 were used to test Hypotheses 2–4 separately.ResultsDescriptive statistics and correlation resultsTable 2 shows the information on the descriptive statistics and correlation results for all variables. The coefficient of the correlation between AI technology and entry mode is 0.09, with significance at the 1 percent level. The majority of the correlation coefficients between any two variables fall below 0.5. Additionally, upon assessing the variance inflation factor of the models, we observed that both the highest and mean values remained under 5. All the above results indicate that the potential multicollinearity issue does not exist in our study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Note: N = 654; Correlations greater than |0.01| are significant at the 0.05 level.

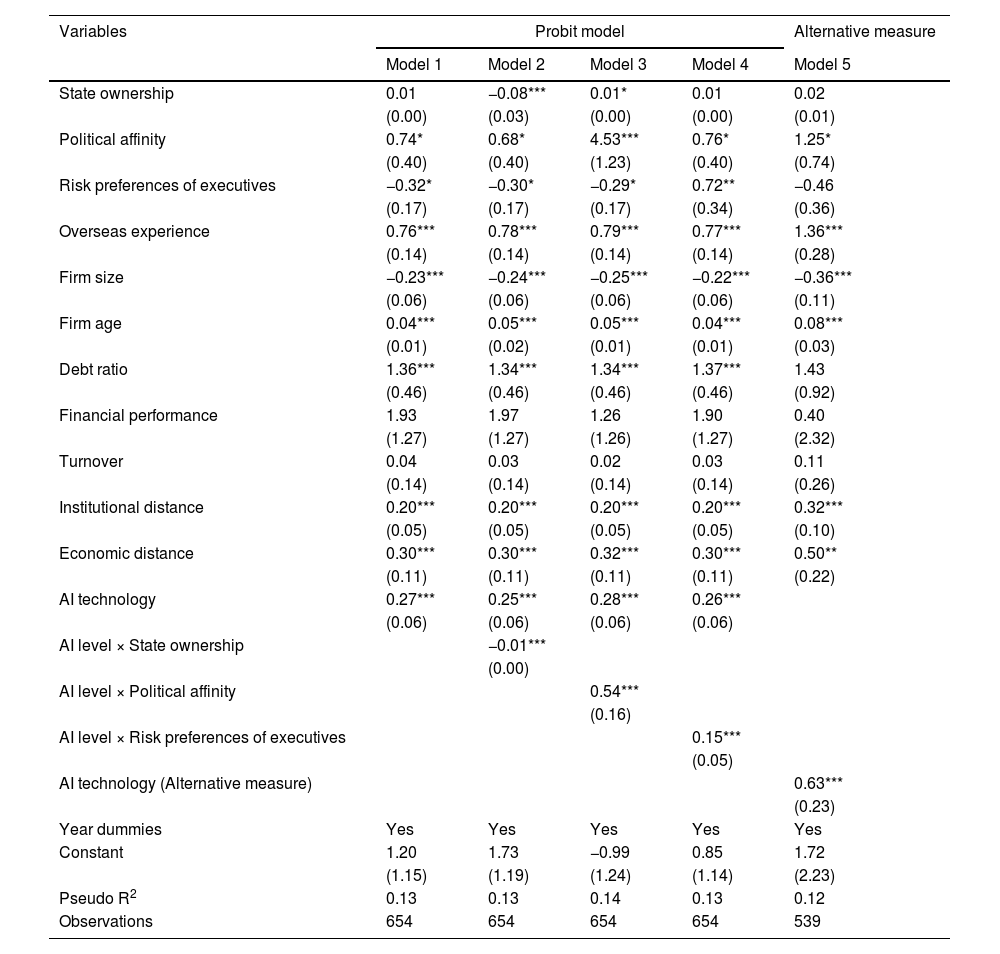

The findings pertaining to our initial hypothesis are exhibited in Table 3. Model 1 serves as the foundational model incorporating all pertinent control variables. In Model 2, we find that the coefficient of AI technology is statistically positive with significance at the 1 percent level (β=0.46;p<0.01). This confirms our hypothesis that firms’ AI technology will improve their ability to process information. Therefore, firms do not need to cooperate with local firms to reduce risk, which is consistent with the view that firms tend to choose wholly-owned firms when they face less uncertainty.

Main results.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

In Model 3, our examination seeks to determine the negative moderating effect of state ownership. Our analysis reveals that the coefficient of the interaction term between AI technology and State ownership is negative, with the significance at the 1 percent level (β=−0.02;p<0.01). This confirms that state ownership can negatively moderate the main relationship, and hypothesis 2 can be proved. The finding indicates that as the level of state ownership in an energy firm intensifies, the level of regulatory and legitimacy concerns in the host country amplifies, thereby diminishing the favorable impact of AI technology.

In Model 4, we test whether strong political affinity positively moderates the role of firms’ AI technology in their wholly-owned entry mode. The findings reveal that the coefficient of the interaction term between AI technology and Political affinity is positive with the significance at the 1% level (β=0.96;p<0.01). In countries with high political affinity, specifically close political relations with China, the stronger the role played by energy firms’ AI technology in choosing wholly-owned entry mode.

Finally, in Model 5, we test the positive moderating effect of executive risk preferences. The coefficient of the interaction term between AI technology and the Risk preferences of executives is positive, with the significance at the 1 percent level (β=0.24;p<0.01). This indicates that the higher the executives’ risk tolerance, the more inclined they are toward wholly subsidiary entry strategies. The pursuit of risk makes executives more likely to choose a high-commitment entry mode, and on the other hand, risk-averse executives may increase their confidence in AI technology. Therefore, hypothesis 4 can be supported.

Robustness checkInstead of the logistic regression model, we used an alternative model to test the robustness of the results. We used the Probit regression model as the alternative model, as it is also estimated by the dummy variable as the dependent variable in the model. Table 4 reports these robustness results. The coefficient of AI technology in Model 1 is positive with the significance at the 1 percent level, and the coefficients of the interaction terms, including AI technology with State ownership in Model 2, Political affinity in Model 3, and Risk preferences of executives in Model 4 are statistically significant and align with the primary results presented in Table 3. Therefore, these results are stable when using the alternative model.

Robustness results.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

In addition, we used an alternative measure of our important variable, AI technology, to check whether the results were robust. In contrast to the main measurement using text analytics, we followed the methods of Acemoglu and Restrepo (2018) and then measured the actual investment of AI in the firms by capturing the use of industrial robots. Specifically, the variable was calculated as the ratio of the book value of industrial robots to total employees. Model 5 of Table 4 reports the results that the coefficient of AI technology is positive with the significance at the 1% level, supporting the robustness of our main results.

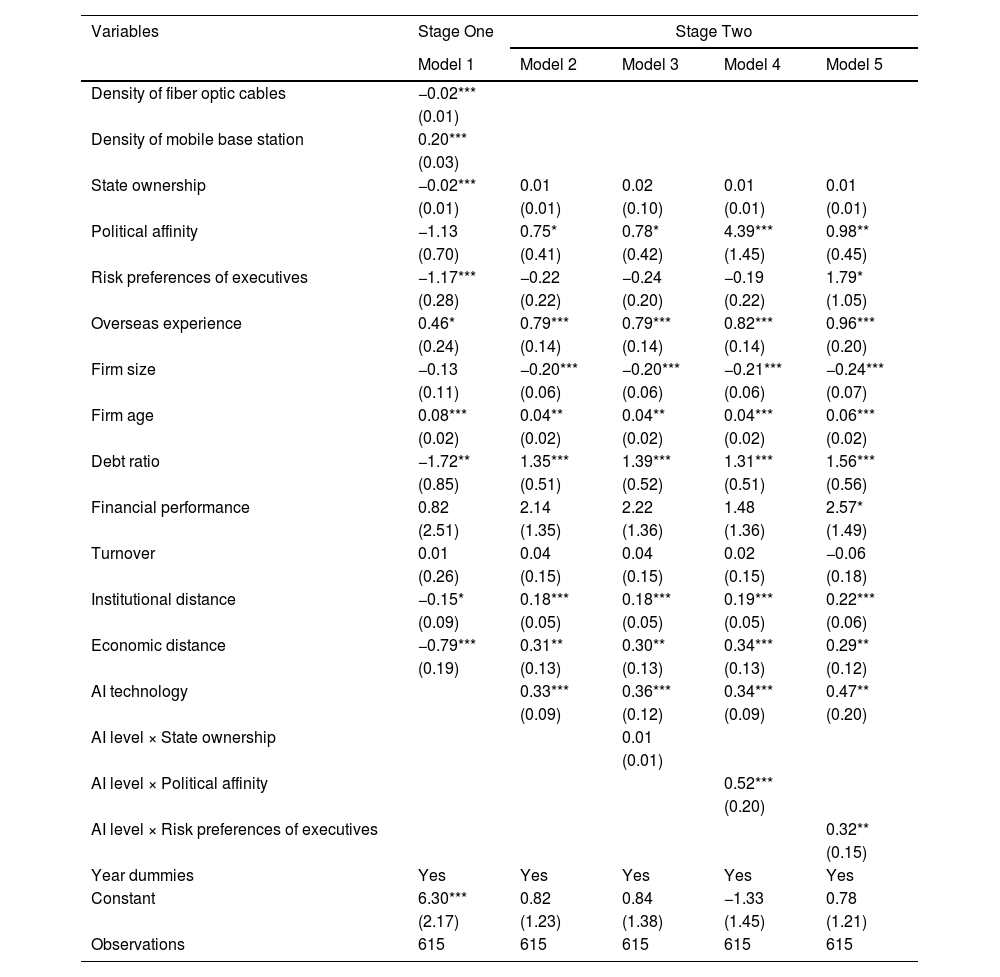

Endogeneity testPotential endogeneity issues, specifically reverse causality between AI technology and entry mode, may interfere with our results and should be addressed with more tests. We adopted the Probit model with continuous endogenous covariates (IV-Probit) to eliminate the effect of endogeneity. We carefully selected two instrument variables: Density of fiber optic cables and Density of mobile base stations in the province where the parent firms are located (Du, Hou, Zhou & Ren, 2022; Hossain et al., 2022; Wang, Chen & Chen, 2024). These two variables can reflect the level of information technology infrastructure in the region and are highly correlated with AI technology while unlikely to affect firms’ overseas entry mode directly.

Table 5 reports the results of the endogeneity test. Amemiya-Lee-Newey test in the over-identification test does not reject the original hypothesis (p=0.36), indicating the exogenous instruments we used in our study. The results of the Wald test (p=0.000) suggest that the instrumental variables we used are not weak instrumental variables. Model 1 reports the regression results of the IV-Probit first stage, showing that the instrumental variables are significantly associated with AI technology. Models 2–5 exhibit the second-stage regression results. The coefficient of AI technology is statistically positive and significant in Model 2 (β=0.33;p<0.001), suggesting that our main relationship remains the same after addressing the potential endogeneity issues. The results of Models 3–5 suggest that all moderating results are still robust except for state ownership.

Results of the endogeneity test.

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses; *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

With the wave of digital globalization, firms in emerging markets are actively seeking global expansion. It is important to further understand the impact of digitization on business strategy decisions (Menz et al., 2021). Previous studies have typically focused on the impact of digitization as a whole on the business as a unit or on specific aspects of it (Lee et al., 2019; Tortora, Chierici, Briamonte & Tiscini, 2021). Our study follows a small number of emerging studies that focused on exploring how a particular technology of digitization supports the internationalization activities of firms (Hosseini, Fallon, Weerakkody & Sivarajah, 2019; Shamim, Zeng, Choksy & Shariq, 2020). Through a deep understanding of AI, our study sheds light on how the development of specific digital technologies can influence firms’ internationalization activities as well as their strategic decisions (Meyer et al., 2023).

Scholars have clearly recognized the role of AI in business with enhanced information processing and analytical capabilities that can extend human cognitive abilities and support business decisions (Jarrahi, 2018). Specifically in the field of international business, AI can help organizations achieve faster expansion of exports and overseas markets (Kopalle et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023). In this study, we focus on the entry modes of MNEs in entering foreign markets, seeking to explain the antecedent mechanisms of this strategic choice based on the existing understanding of AI. We argue that technological capabilities provide the basis for firms to achieve heterogeneity (Ederington & McCalman, 2008), while at the same time undermining host country uncertainty (Li & Xiong, 2022). Consistent with the prior literature on MNE strategy, our findings suggest that firms are more willing to make higher resource commitments in international expansion when the technological capabilities they possess create competitive advantages (Brouthers, 2002; Li & Xiong, 2022; Wei, Zheng, Liu & Lu, 2014).

We also find evidence on the boundary conditions, aiming to better understand the relationship between AI technology and entry mode to foreign markets. Specifically, a higher share of state ownership weakens the positive impact of AI technology because state ownership often implies control by the home government and is associated with national security. In addition, the higher the political affinity between the two countries, the more firms can exert a positive influence of AI technology on the decision to enter wholly-owned modes. This positive influence is also enhanced by the risk preferences of executives, with risk-averse executives being more confident and willing to make greater commitments than risk-averse executives.

Theoretical contributionsOur study contributes to the literature on digitization and international business. Digitalization plays an important role in international business (Meyer et al., 2023). Scholars have previously focused on the impact of digitization as a whole on entry mode (Ekeledo & Sivakumar, 2004a; Li et al., 2021), but have not specified how specific technologies of digitization support firms’ entry mode strategies. We build on the study of Reim et al. (2022)) in exploring the impact of AI as an important digital technology on entry mode. Our study complements the direction of studies on AI technologies of MNEs, where previous discussions have focused on the role of AI in supporting exports, marketing, human resources, and performance (Denicolai et al., 2021; Kopalle et al., 2022; Meyer et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023).

This study also contributes to the role of AI technology in knowledge management. AI can help organizations to share tacit knowledge, convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge, and analyze explicit knowledge, thus helping to create new knowledge (Li, Bastone, Mohamad & Schiavone, 2023b; Obreja, Rughiniș & Rosner, 2024). At the same time, AI generates new knowledge by processing existing information (Abdelaty & Weiss, 2023; Nemati, Steiger, Iyer & Herschel, 2002), which increases the knowledge base needed for employees of the organization to innovate. The analytical and predictive capabilities of AI technology also provide knowledge and technical support for managers’ decision-making. However, there is little research on the path of “how AI technology influences knowledge systems to influence firms’ entry mode decisions.” We argue that AI technology can help organizations acquire knowledge from overseas markets faster and easier and convert that knowledge into explicit, exploitable solutions through its powerful processing capabilities. Our study further extends our understanding of how knowledge processing affects firms’ internationalization paths by managing knowledge from the technological side through information systems, which enriches the literature on technology and knowledge management.

In addition, this study contributes to the energy economics literature. Prior investigations into energy firms’ entry mode have predominantly centered on country, industry, and market perspectives (Koch & Meckl, 2014; Zhang, Wang, Wang & Zhao, 2015) and have not landed on specific technology perspectives. On the other hand, our findings suggest that the impact of digital technologies on energy firms is not limited to influencing internationalization by changing business models (Bohnsack, Ciulli & Kolk, 2021) or accelerating internationalization through digital marketing (Bovina, 2020), but can also influence the choice of entry mode strategies through the information processing capabilities of AI technology. We also extend the boundary conditions by confirming the moderating effects of ownership type, political affinity, and executive risk preference at different levels.

Practical implicationsFirst of all, this study explores the impact of AI technology on firms’ foreign market entry mode, providing firms with an important reference for formulating overseas market entry strategies in the context of globalization. Under the current digitalization and intelligence development trend, firms face an increasingly complex and changing international market environment, and choosing entry mode has become the key to their overseas expansion. This study reveals how AI technology can help firms understand foreign markets through information processing capabilities and then influence their entry mode choices, providing a framework for firms to formulate foreign market entry strategies based on technological innovation.

Second, this study can lead to the discovery of the application of AI technology in foreign markets among firms. For example, firms can utilize more AI technologies in market research, competitive analysis, and consumer insights to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of firms’ decision-making during and after entering foreign markets. This will directly guide firms to better use AI technology to optimize their foreign market strategies and improve their international competitiveness.

In addition, this study promotes the commercial application of the technology and the accumulation of corporate knowledge. By combining AI technology with firms’ foreign market entry mode, this study not only promotes the innovative application of AI technology in international business but also provides firms with valuable practical experience and knowledge accumulation. These will help firms better understand and grasp international market dynamics, enhance their market sensitivity and resilience, and lay a solid foundation for their long-term development.

Our study also provides guidance and practical implications for policymakers. The energy sector is unanimously recognized as an area that affects national security and economic development, and OFDI in the energy sector is a common tendency not only in China but also in the US, European countries, and other countries. The findings in this paper confirm that energy firms can choose a wholly-owned entry mode, which means more returns and greater control. This helps policymakers recognize and promote the advancement of AI technology in energy firms in their countries by developing relevant promotional policies.

Limitations and future research directionsOur study has certain limitations, which offer opportunities for future research. First, our sample only includes Chinese-listed firms, and we did not include small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Due to the differences in the size of firms in terms of finance, technology, and expertise, international business studies have also recently been paying more attention to how SMEs internationalize. This classification may have a potential impact on foreign market entry mode. It remains a question of whether our findings apply to unlisted firms. Second, we have only examined the impact of AI technology on the foreign market entry mode of energy firms. Future research could consider the impact of AI technology in other sectors. In addition, the generality of our results may be limited to the Chinese context. We call for future studies to investigate our hypotheses under different and complex contexts to extend the knowledge.

ConclusionThis study examines the internationalization strategies of emerging market MNEs under the wave of digitization. Most previous studies on international entry mode strategies have used digitalization as a holistic activity. In order to investigate the role of specific technologies of digitization in the internationalization activities of firms, the most representative and cutting-edge digital technology, AI, is selected for this study. We investigated the effect of AI's information processing ability on MNEs’ entry modes. Our results show that AI technology can reduce uncertainty in the host market, which is consistent with previous studies in the literature. In this case, firms are more confident in making higher resource commitments.

In addition, we find that the higher the percentage of state ownership, the weaker the positive impact of AI technology, as state ownership often implies control by the home government and is associated with national security. The higher the political affinity between the two countries, the more firms can utilize the positive impact of AI technology on the decision of the sole proprietorship entry mode. This positive impact is also enhanced by the risk preference of executives, with risk-preference executives being more confident and willing to make greater commitments than risk-adverse executives.

This study contributes to the literature by examining the specific role of AI technology on corporate international strategy. It provides a new direction for the specific application of AI in international business.

FundingThis study was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundationfor Excellent Young Scholars (2023HWYQ-090), the Science and Technology Support Plan for Youth Innovation of Colleges and Universities of Shandong Province of China (2022RW033), the Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (tsqn202312167), and the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2023QG059).

CRediT authorship contribution statementWei Liu: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Mengxiao Cao: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jianwen Zheng: Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Justin Zuopeng Zhang: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization.