Since the appearance of the first cases of infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the Chinese province of Hubei in December 2019, the disease caused by this pathogen has spread across the world, with high infectivity and mortality rates. The typical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection include fever, asthenia, and dry cough1; more severe cases present respiratory insufficiency secondary to alveolar damage caused by massive release of proinflammatory molecules.2 However, little is known about the neurological complications associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.3 We present a case of progressive tetraparesis, global areflexia, and fatal bulbar syndrome, clinically compatible with acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Our patient was a 76-year-old woman with previously good quality of life who was transferred to the emergency department at Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra due to a 10-day history of lower back pain radiating to the backs of the legs and progressive tetraparesis with distal-onset paraesthesia. Pain was bilateral, predominantly affecting the right side; it was more intense during the night, leading to difficulties falling asleep. The patient was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pyrazolones, and transdermal morphine. Progressive, predominantly proximal weakness was observed in the lower limbs; 2 days before our assessment, she presented weakness of the upper limbs, with functional limitation.

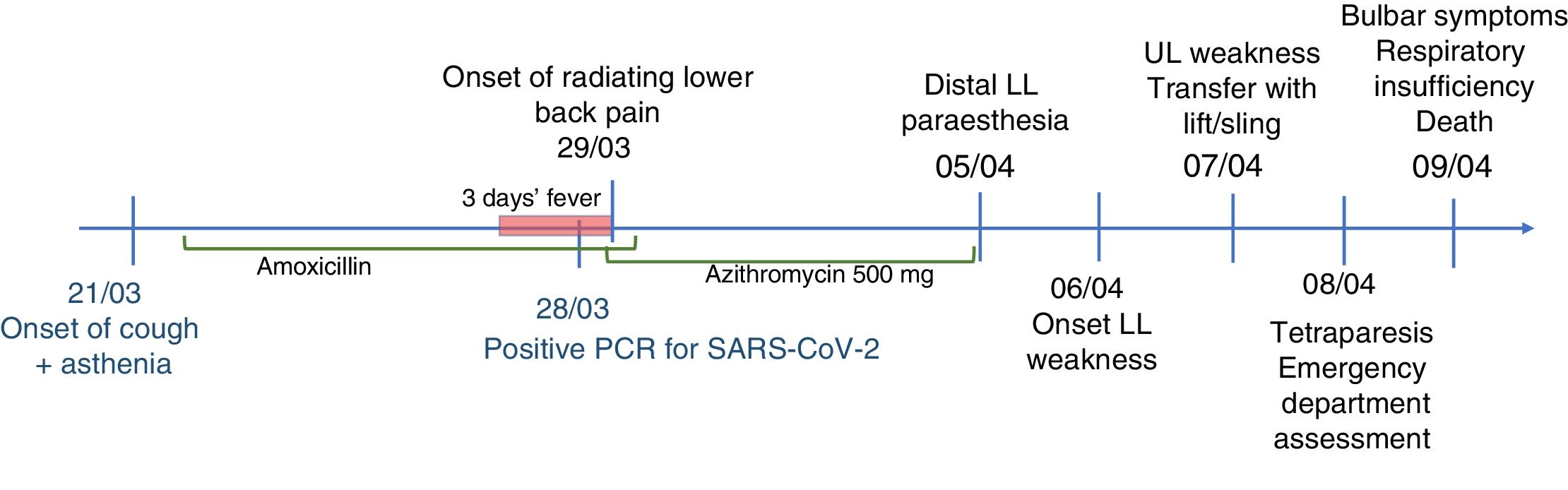

Eight days before symptom onset, the patient had presented cough and fever without dyspnoea, lasting 72hours, which were treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and azithromycin. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test yielded positive results for SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 1).

The neurological examination revealed predominantly proximal muscle weakness in the upper limbs of 0/5 in proximal muscles, and 4/5 in distal muscles; in the lower limbs, we observed proximal weakness of 0/5 in the psoas and 1/5 in quadriceps, and distal weakness of 2–3/5 in the tibialis anterior muscles. The patient presented global areflexia and hypoaesthesia in both legs, progressing distally from the knees.

An emergency blood analysis showed mild thrombocytopaenia (102×109/L) and high levels of fibrinogen (470mg/dL) and d-dimer (773ngFEU/mL), with no other alterations. A head CT scan revealed no alterations, and a cervical and thoracic spine CT scan showed degeneration of the vertebral bodies without invasion of the spinal canal. A chest CT scan showed a pattern compatible with mild lung involvement due to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Four hours after admission, the patient presented dysphagia to liquids and progressively to solids, nasal voice, and difficulty swallowing saliva, with progressive onset of respiratory failure. Her condition progressively deteriorated, and she required oxygen therapy (60% FiO2), with oxygen saturation levels at about 91%, which is not suggestive of blood–air barrier dysfunction or impaired gas exchange. The patient finally died 12hours after onset of the bulbar symptoms.

The main limitation of our case report is the lack of complementary tests supporting the diagnostic suspicion, given the rapid progression of symptoms and the context of the public health crisis. However, the symptoms of progressive tetraparesis and areflexia meet the main clinical criteria for diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome.4 The presence of symmetrical motor involvement, mild to moderate sensory alterations, the radiating lower back pain at onset, and the bulbar symptoms also support this diagnosis.5,6 Diagnosis of such other conditions as myasthenic syndrome seems less likely, due to the presence of sensory symptoms.

The literature includes few data on the development of acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy secondary to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In some of the cases reported, the temporal association is unclear and the SARS-CoV-2 infection may be incidental, rather than the aetiological cause.7 However, the presence of a viral or bacterial infection or vaccination in the weeks before symptom onset, acting as trigger factor for dysimmunity, is one of the classic pillars of this process. In the context of infection with similar coronaviruses, acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy has been associated with Bickerstaff encephalitis in a patient with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection.8 Other pathogenic agents, such as human coronavirus OC43, have also been associated with cases of acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy.9 Further studies are needed to understand the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the central nervous system and the possible development of neurological complications, such as acute inflammatory polyradiculoneuropathy.

Please cite this article as: Marta-Enguita J, Rubio-Baines I, Gastón-Zubimendi I. Síndrome de Guillain-Barré fatal tras infección por el virus SARS-CoV-2. Neurología. 2020;35:265–267.