Social media is a powerful tool in providing information and support for patients with chronic diseases. The aim was to assess the link between using social media and depression in a sample population of Turkish ankylosing spondylitis (AS) patients.

MethodsThe patients completed a self-administered questionnaire, which was designed by the authors. Their demographic data, educational status, diagnosis, and favorite social network were also recorded. The Beck Depression Inventory-IA amended (revised) (BDI-IA-Turkish) was used to screen the AS patients for depression.

ResultsA total of 155 AS patients were included in the study. The depression scores of the patients who used the Internet (12.18±6.85) and social media (12.35±6.90) were compared with those who did not (27.19±10.51 vs. 25.20±11.66) and a significant difference (p≤0.001) was found. Smartphone users were in the majority (73.5%). WhatsApp was the preferred social network (66.5%), followed by Facebook (52.9%), Instagram (52.3%), Twitter (19.4%) and Pinterest (5.8%). Social media users and non-users were similar in age, gender, educational level and marital status. There were no significant differences in terms of the type and duration of social media use with depression score.

ConclusionThe results of this cross-sectional study confirmed that using social media can help patients with AS to cope with or be less affected by depression. Finding the most appropriate and commonly used form of social media may be an important concept for stewardship in health policies.

Las redes sociales son una herramienta poderosa para brindar información y apoyo a los pacientes con enfermedades crónicas. Se buscó evaluar el vínculo entre el uso de las redes sociales y la depresión en una muestra de población de pacientes turcos con espondilitis anquilosante.

MétodoLos pacientes completaron un cuestionario autoadministrado que fue diseñado por los autores. También se registró información sobre sus características demográficas, estado educativo, diagnóstico y red social favorita. Se utilizó el Inventario de Depresión de Beck-IA enmendado (revisado) (BDI-IA-Turco) para detectar depresión en los pacientes con espondilitis anquilosante.

ResultadosSe incluyeron en total 155 pacientes con espondilitis anquilosante. Se compararon las puntuaciones de depresión de los pacientes que utilizaron Internet (12,18±6,85) y redes sociales (12,35±6,90) con los que no lo hicieron (27,19±10,51 vs. 25,20±11,66), y se encontró una diferencia significativa (p≤0,001). Los usuarios de teléfonos inteligentes constituyeron una mayoría (73,5%). WhatsApp® fue la red social preferida (66,5%), seguida de Facebook® (52,9%), Instagram® (52,3%), Twitter® (19,4%) y Pinterest® (5,8%). Los usuarios y los no usuarios de las redes sociales fueron similares según su edad, sexo, nivel educativo y estado civil. No hubo diferencias significativas entre el tipo y la duración de las redes sociales con relación al puntaje de depresión.

ConclusiónLos resultados de este estudio transversal confirmaron que el uso de las redes sociales puede ayudar a los pacientes con espondilitis anquilosante a afrontar o dificultar la posibilidad de verse afectados por depresión. Encontrar las redes sociales más apropiadas y de uso común puede ser un concepto importante para la rectoría en las políticas de salud.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease that leads to significant impairment in functioning and health.1 The prevalence of AS has been estimated to be 0.32%–1.4% in different surveys.2,3 Living with the symptoms and consequences of AS, such as impaired physical functioning, pain and fatigue, could induce psychological disorders, such as depression. Mental health is affected in patients with AS, including an increased risk of depression when compared to the general population. Numerous studies have already shown that the prevalence of depression is higher in patients with AS when compared to the general population.4,5

The advance of the Internet is radically changing communication. The Internet has become an important source of information in parallel with the increase in its use in society. Obtaining online health information has become increasingly popular and people often use the Internet as a source of health information. The term ‘social media’ refers to the various internet-based networks that enable users to interact with others, verbally and visually.6 Social media has recently become part of the daily activities of many people. Many of them spend hours each day on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and other popular social media. Moreover, the number of social media users worldwide in 2019 was 3.484 billion, and up to 9% year-on-year.7 Studies have shown the benefits of enabling people to express their thoughts and feelings, and to receive social support. The impact of social media on individual or institutional communication, modernizing environment and knowledge acquisition is non-negligible in the era of digitization.8 Social media channels have gained an important place for knowledge and awareness of the diseases. Patients with rheumatic diseases are very eager to use internet to better understand their chronic diseases.9

The use of internet and social media are important instruments for effective education and communication. One of the beneficial aspects of thus in AS patients has been the use of social networks for better support in health-related coping, social interactions, and patient information processes. This study aimed to review the positive and/or negative effects of using internet and social media on depression in AS patients.

Patients and methodsPatientsInclusion criteria of the studyInclusion criteria were a confirmed diagnosis of AS according to the Assessment in SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS) classification criteria, and being aged ≥18 years.10

Exclusion criteriaPatients with mental or cognitive disorders, neurological disease, uncontrolled diabetes, cardiovascular disease, the presence or history of psychiatric disorder and the use of anti-psychiatric medication within three months, poor literacy, or lack of consent were excluded from the study.

Demographic findingsPatients were requested to answer the self-administered questionnaire designed by the authors. We used a survey that is composed of multiple-choice questions and administered randomly to outpatients by a physician and in-person survey method. The survey included multiple type of questions including, multiple choice, checkbox, close-ended followed by open-ended and non-response answer options. No standardized validation or reliability testing method was used. Disease-specific assessments was included disease duration, HLA B27 positivity and medication use; scores on the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) to assess disease activity and physical function, respectively. Participants completed with questions including the level of educational attainment (four categories), marital status (two categories), smoking status (two categories), using social media (yes/no), having an internet connectable device (four categories), using social networks (yes/no), type of social networks (five categories) and use social media for information (yes/no). Furthermore, they were asked whether they use social media as a communication tool for health-related information with their rheumatologists, other healthcare providers and rheumatology patients.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. Data confidentiality was guaranteed.

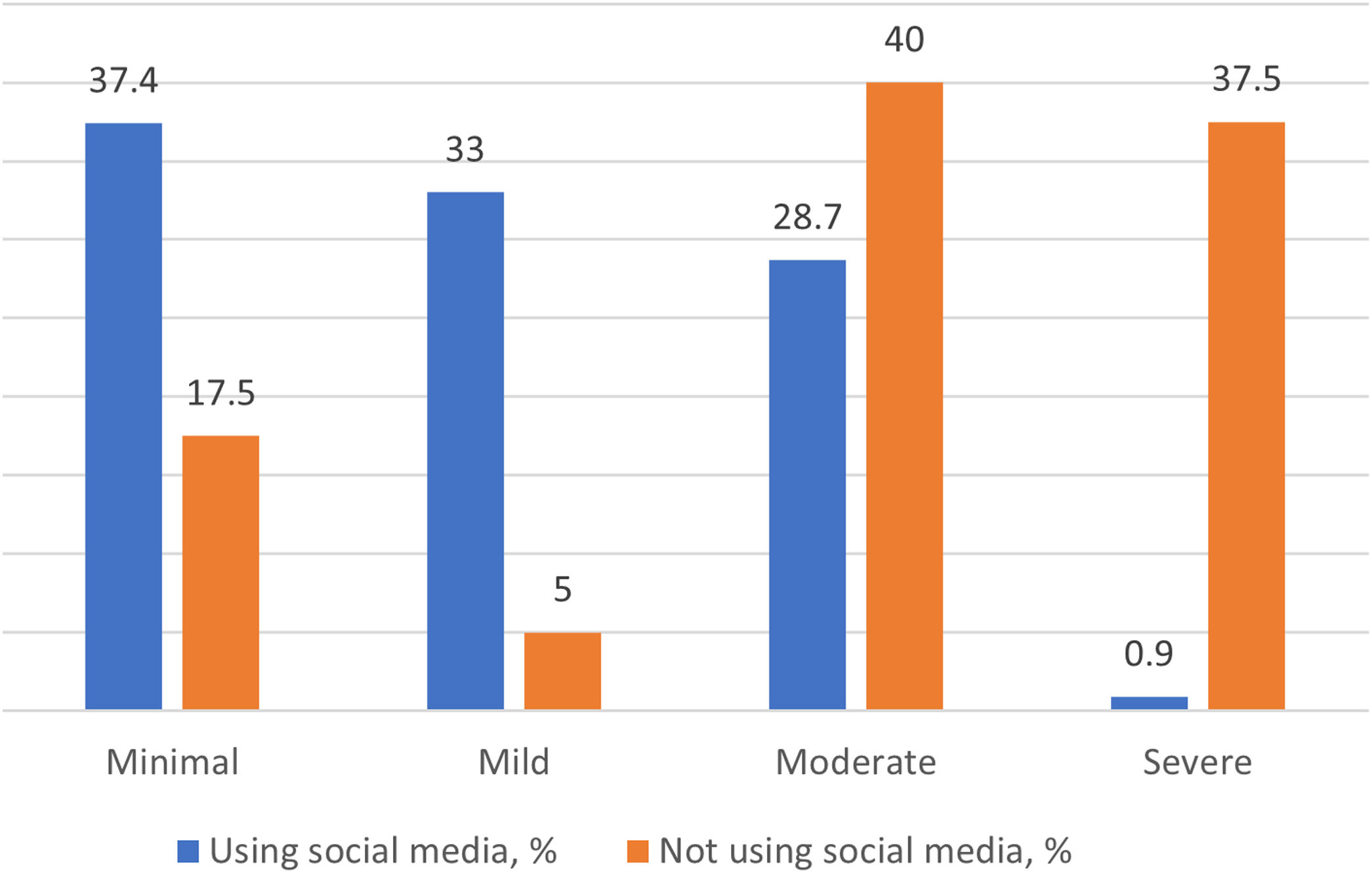

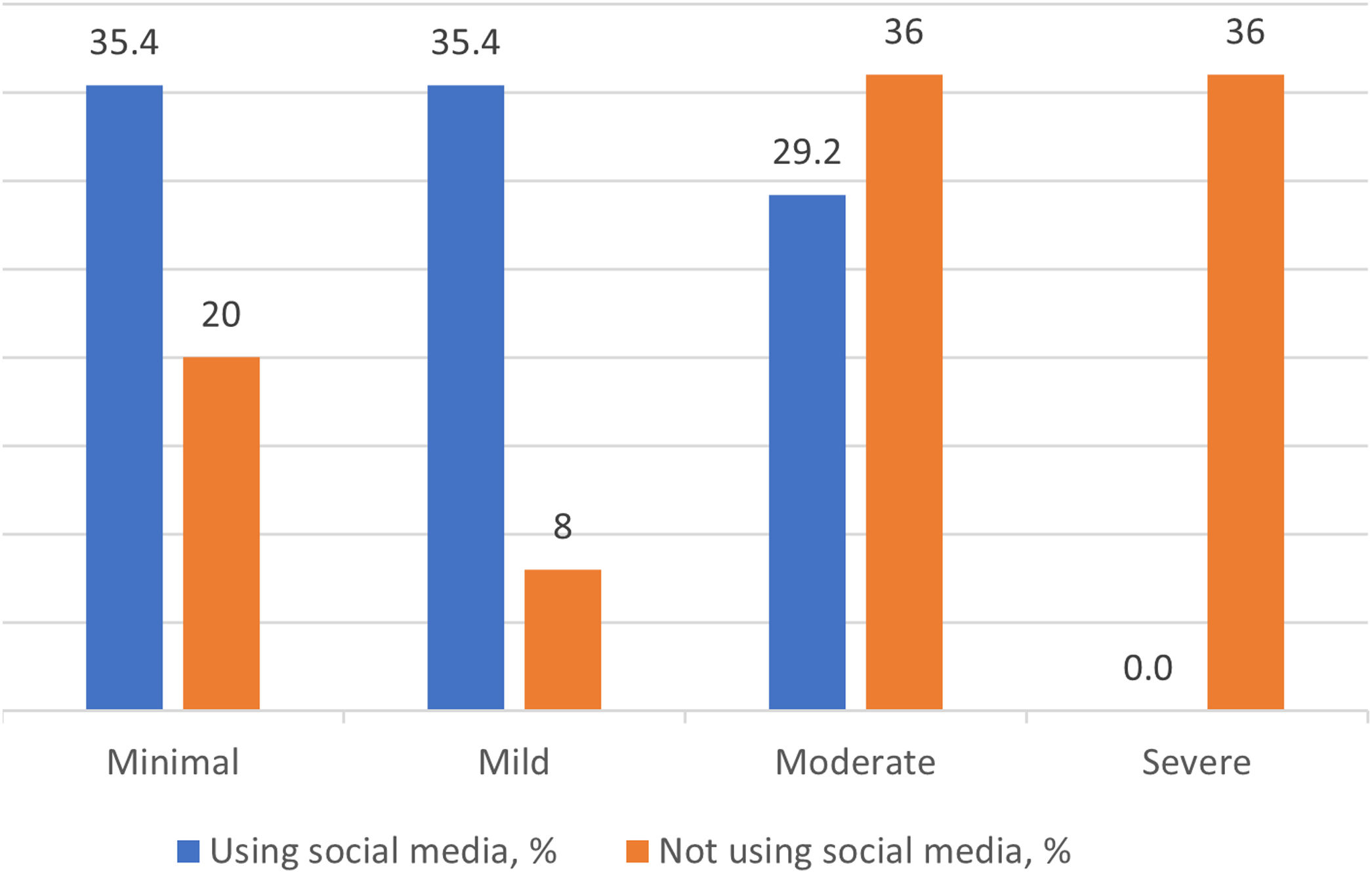

Beck Depression Inventory-IA (BDI-IA)The Beck Depression Inventory-IA amended (revised) (BDI-IA) was developed and validated using psychiatric and normal populations. The original BDI was based on clinical observations and patient description. The BDI-IA contains items that reflect the cognitive, affective, somatic, and vegetative symptoms of depression.11 The following guidelines have been suggested to interpret the BDI-IA: minimal range=0–9, mild depression=10–16, moderate depression=17–29, and severe depression=30–63.

Compliance with ethical standardsThe study was approved by the local ethics committee (Date: 19/08/2020 Decision No: 2020/37) and written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients and control subjects. All of the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statistical analysisIBM SPSS 22.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) with a 95% confidence interval and as number and percentage as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Statistical differences between the parametric data of two groups were analyzed using the student t-test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine differences between the nonparametric data. p≤0.05 was considered as statistically significant for all of the tests.

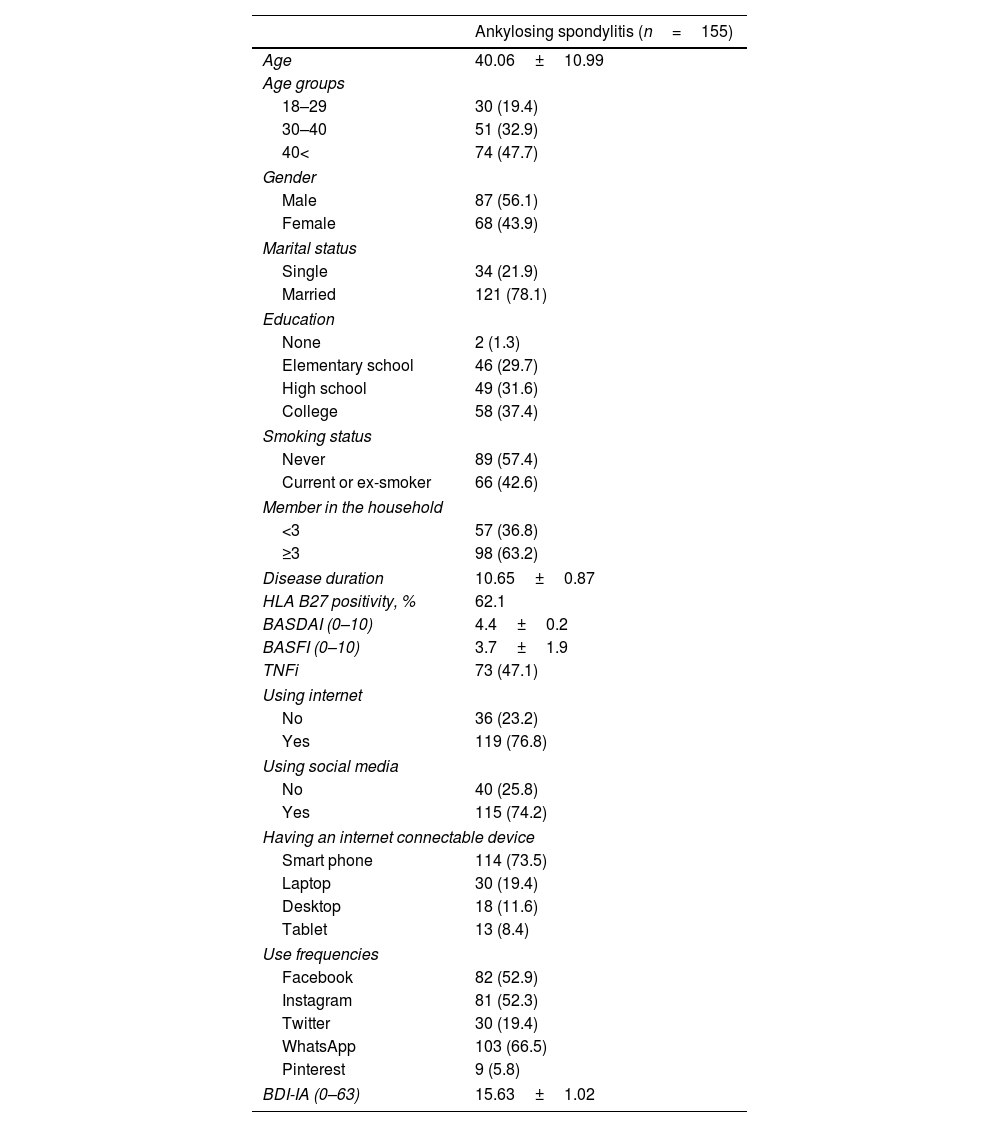

ResultsDemographic findings of the AS patients are shown in Table 1. The depression scores between the patients who used the Internet (12.18±6.85) and social media (12.35±6.90) were compared with those who did not (27.19±10.51 vs. 25.20±11.66) and a significant difference (p≤0.001) was found. Smart phone users were in the majority (73.5%). WhatsApp was the most preferred social network (66.5%), followed by Facebook (52.9%), Instagram (52.3%), Twitter (19.4%), and Pinterest (5.8%). The percentage of patients who use social media for searching about health-related information is 68.9%. Facebook was the most preferred social network for the information (45.9%). Information sources among social media users were following their rheumatologist and other healthcare givers and/or rheumatology patients. Social media users and non-users were similar according to their age, gender or educational status, and marital status. There were no significant differences between the type and duration of social media with the depression score. There were no differences in the prevalence of depression between users of the different social networks. Moreover, based on a cut-off of 3 types of social media, there was significant difference in the status of depression among patients (<3, n: 64, 14.71±6.77, vs. ≥3, n: 51, 10.47±6.45, p≤0.001). There was no difference in depression scores according to site, age, and number of households. A weak correlation was observed between the BASDAI/BASFI and BDI-IA depression variables (r=0.167, p=0.019; r=0.188, p=0.022, respectively). There was a significant difference among the severity of depression in terms of the use of social media (p≤0.001) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, social media had a positive effect on the severity of depression in patients who were using tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) (p≤0.001) (Fig. 2). Of the Internet users, 41.2% did research on AS prior to their diagnosis, and 77.9% did research after their diagnosis. Moreover, 70.8% searched for the treatment online, and 36.6% of the TNFi users searched the internet prior to undergoing treatment.

Demographic findings of the AS patients.

| Ankylosing spondylitis (n=155) | |

|---|---|

| Age | 40.06±10.99 |

| Age groups | |

| 18–29 | 30 (19.4) |

| 30–40 | 51 (32.9) |

| 40< | 74 (47.7) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 87 (56.1) |

| Female | 68 (43.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 34 (21.9) |

| Married | 121 (78.1) |

| Education | |

| None | 2 (1.3) |

| Elementary school | 46 (29.7) |

| High school | 49 (31.6) |

| College | 58 (37.4) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 89 (57.4) |

| Current or ex-smoker | 66 (42.6) |

| Member in the household | |

| <3 | 57 (36.8) |

| ≥3 | 98 (63.2) |

| Disease duration | 10.65±0.87 |

| HLA B27 positivity, % | 62.1 |

| BASDAI (0–10) | 4.4±0.2 |

| BASFI (0–10) | 3.7±1.9 |

| TNFi | 73 (47.1) |

| Using internet | |

| No | 36 (23.2) |

| Yes | 119 (76.8) |

| Using social media | |

| No | 40 (25.8) |

| Yes | 115 (74.2) |

| Having an internet connectable device | |

| Smart phone | 114 (73.5) |

| Laptop | 30 (19.4) |

| Desktop | 18 (11.6) |

| Tablet | 13 (8.4) |

| Use frequencies | |

| 82 (52.9) | |

| 81 (52.3) | |

| 30 (19.4) | |

| 103 (66.5) | |

| 9 (5.8) | |

| BDI-IA (0–63) | 15.63±1.02 |

Continuous variables were presented as mean (SD) and categorical variables were presented as number (%). BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BDI-IA, Beck Depression Inventory-IA; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors; HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

The results of this cross-sectional study revealed that a great majority of the patients with AS owned at least one device to connect to the internet and was using at least one social media platform regularly. Facebook and WhatsApp were the most preferred social platforms. The most of patients used social media for health-related purposes. Furthermore, using social media for searching about health and medical treatment information had a positive effect on the severity of depression in patients who were using TNFi. Our study showed that using social media of AS patients have low depression scores. To our knowledge, this study was the first to shed light on the positive effects of the Internet and social media on depression in AS patients.

Several studies have already shown that depression is the most common comorbidity in patients with AS.4,12,13 Meesters et al. showed that the consultation rate for depression is increased by more than 60% in AS patients, with women having a somewhat larger increase in risk.5 The BDI has previously been used to assess depression in studies of rheumatic disorders. The diagnosis of depression in rheumatic diseases is important, because this psychological state may influence other outcomes, such as compliance with medication and disease activity.14

Reviewing the recent literature, it is notable that technology is becoming an important part of medical practice from diagnosis to treatment. One of the useful aspects of technology in rheumatologic diseases has been the use of social networks, for better support in health-related coping, social interactions, and patient informing processes.15 The Internet is being increasingly used as an important source of health-related information, particularly in chronic diseases.16 This study was the first to shed light on the positive effects of internet and social media on depression in AS patients. The grounds of this merit can be implied in a number of previous studies, such as patients with RA use the Internet for a variety of purposes, including looking up health information, and more than half of the North Americans with access to the Internet use it at least once a month as a source of health-related information.17

Exercise therapies are the cornerstone of the treatment of AS. Visual materials and videos help to learn accurate exercise methods. Kocyigit et al. investigated YouTube as a source of patient information for AS exercises. The authors concluded that YouTube can be considered as an important source of high-quality videos for AS exercises.18

On the other hand, Jeri-Yabar et al. showed that excessive social media usage was associated with depressive symptoms in university students. In this study, the authors concluded that a Twitter user was an associated factor for the development of depressive symptoms and that being a frequent Facebook user was actually a protective factor against depressive symptoms. This may have been because Facebook is more personal, and is based more on real-life friends, whereas Instagram or Twitter are not, and people receive more feedback and support from friends than on the other sites.19 Another study supported the conclusion that Facebook is not an associated factor for depression symptoms.20 In the current study, according to the number of social media users, the depression score was found to be lower in those who used 3 or more types of social media.

WhatsApp seemed to be preferred online application method in patients for communication. This can be due to the widespread use of WhatsApp, which is the most common mobile application in Turkey.21 Moreover, it has an advantage of better preserving privacy compared to other social media platforms.

Finding the most appropriate and commonly used social media may be an important concept for stewardship in health policies. Useful information shared in the media reduces the need for patients to visit the offices of physicians and hospitals, and also enables them to communicate easily with their trusted physicians. Sharing useful experiences and informing other patients can sometimes prevent unnecessary referrals to the hospital and physician offices. These can save on gasoline, travel costs, and time and shifts.22 It is also notable that sudden outbreaks of public health events results in huge challenges for health service systems. Recent experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has indicated that the necessity of online interventions, especially for mental health disorders, is ineluctable.23,24

Our study has limitations. Geography limited nature of our survey was the major limitation because there can be important variability due to political, economic, cultural, religious, and ethnic factor differences between countries. Access to information content of the disease, frequency of access and the type of page accessed were not evaluated. Our study was done before the Covid-19 pandemic era, and we could not re-assess our survey during the pandemic. Habits, opinions, and preferences are subject to change during pandemics, disasters, and war times.

ConclusionThis study was designed based on the BDI and reports the results based on it. There are clearly further research agendas here, which could fruitfully be pursed considering the other important criteria and depression scorings in the literature. Although this study provides evidence that using social media plays a significant role in the depression scores of AS patients. It should be noted that is had limitations and the ways in which future research might be enhanced. Considering the fact that some cultural variables might affect the outcome of research, further research in other countries and societies may be helpful to find out if the same results will be achieved.

Author contributionsS.U., N.C., I.P. made conceptualization of the study, data curation, interpretation of the data, wrote and adjusted the concept and drafting of the original manuscript.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.