The aim of our research was to compare the evolution of the immune response induced by the BNT162b2 vaccine after the administration of two and three doses in healthcare personnel and in institutionalized elderly people (>65 years of age) without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Material and methodsA prospective observational study was carried out on a convenience sample made up of health workers and institutionalized elderly people, measuring antibodies against S and N proteins of SARS-CoV-2 two and six months after receiving the second vaccine dose, as well as two months after receiving the third dose.

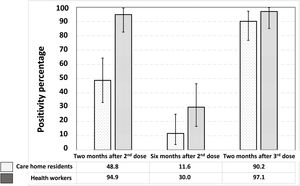

ResultsA significant reduction of the anti-S humoral immune response was reported six months after the second dose of vaccine in both health workers and residents. The administration of a third dose of vaccine induced a significant increase in this antibody response in both investigated groups reaching a similar proportion of responders two months after this third dose.

ConclusionsHumoral immunity induced by two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine in persons without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection wanes over time. The administration of a third dose significantly increases anti-S antibodies being highly recommended, especially in people over 65 years of age.

El objetivo de nuestra investigación fue comparar la evolución de la respuesta inmunitaria humoral inducida por la vacuna BNT162b2 tras la administración de 2 y 3 dosis en personal sanitario y en personas mayores institucionalizadas (>65años) sin infección previa por SARS-CoV-2.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional prospectivo en una muestra de conveniencia conformada por sanitarios y mayores institucionalizados, determinando anticuerpos contra las proteínas S y N del SARS-CoV-2 a los 2 y 6 meses de recibir la segunda dosis de la vacuna, así como a los 2 meses después de recibir la tercera dosis.

ResultadosSe observó una reducción significativa de la respuesta inmune humoral anti-S 6 meses después de la segunda dosis de vacuna, tanto en sanitarios como en residentes. La administración de una tercera dosis de vacuna indujo un aumento significativo de esta respuesta de anticuerpos en ambos grupos, alcanzándose una proporción similar de individuos respondedores a los 2 meses de esta tercera dosis.

ConclusionesLa inmunidad humoral inducida por 2 dosis de la vacuna BNT162b2 en personas sin infección previa por SARS-CoV-2 disminuye con el tiempo. La administración de una tercera dosis aumenta significativamente los anticuerpos anti-S siendo muy recomendable, especialmente en personas mayores de 65 años.

The BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 has proven to be highly effective in the initial clinical trial and, in turn, its effectiveness decreases over time.1 The various epidemic waves of SARS-CoV-2 have also highlighted the limitations of the protection provided by vaccines, probably a consequence of the appearance of new variants and, also, of the progressive loss of vaccine immunity over time.2 In this context of loss of vaccine efficacy against SARS-CoV-2, there is a need for booster doses, especially in those groups most vulnerable to infection.3 Among these particularly vulnerable groups are the institutionalized elderly,4 who were considered the first priority in the national vaccination strategy.5 On the other hand, the immune response to the vaccine is different in those who have had SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to those who have not.6

Therefore, the objective of this article is to compare the evolution of the immune response induced by the BNT162b2 vaccine after two and three doses in health personnel and in institutionalized elderly people without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Material and methodsA prospective observational study was carried out on a convenience sample consisting of health workers and institutionalized older people (>65 years) without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (no history and no specific antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 N protein) and all vaccinated with two doses of BNT162b2. A blood sample was taken from all participants two and six months after receiving the second vaccine dose, as well as two months after receiving the third dose.

The blood samples were processed to obtain serum on the day of collection and the serum was kept at −20°C. The presence of antibodies against the S and N proteins of SARS-CoV-2 was determined using two commercial ELISAs (Human COVID 19 Spike S IgG Coronavirus ELISA Kit, MyBioSource, and Human COVID 19 Nucleocapsid NP IgG Coronavirus ELISA Kit, MyBioSource). The tests were carried out following the manufacturer's instructions. The means of the absorbance normalized to control ([sample absorbance−mean absorbance of negative control]/[mean absorbance of positive control−mean absorbance of negative control]) and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated and compared using T-test for equal or unequal variances, as appropriate, between health workers and care home residents and at different sampling times. The percentage of positives was similarly compared using Chi-square.

All the participants were informed verbally and in writing about the objectives of the study and its potential risks and benefits and signed the informed consent before their inclusion in the study. The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines (CEIM) of the Health Areas of León and El Bierzo (Ref. 2157; 30.03.2021).

ResultsForty health workers (80% women, mean age: 44.7±9.8 years; range: 21–62 years) and 43 care home residents (65.1% women, mean age: 81.3±8.6 years; range: 57–65 years) were included in the study.

No anti-N antibodies were detected in any of them, confirming the absence of previous SARS-COV-2 infection.

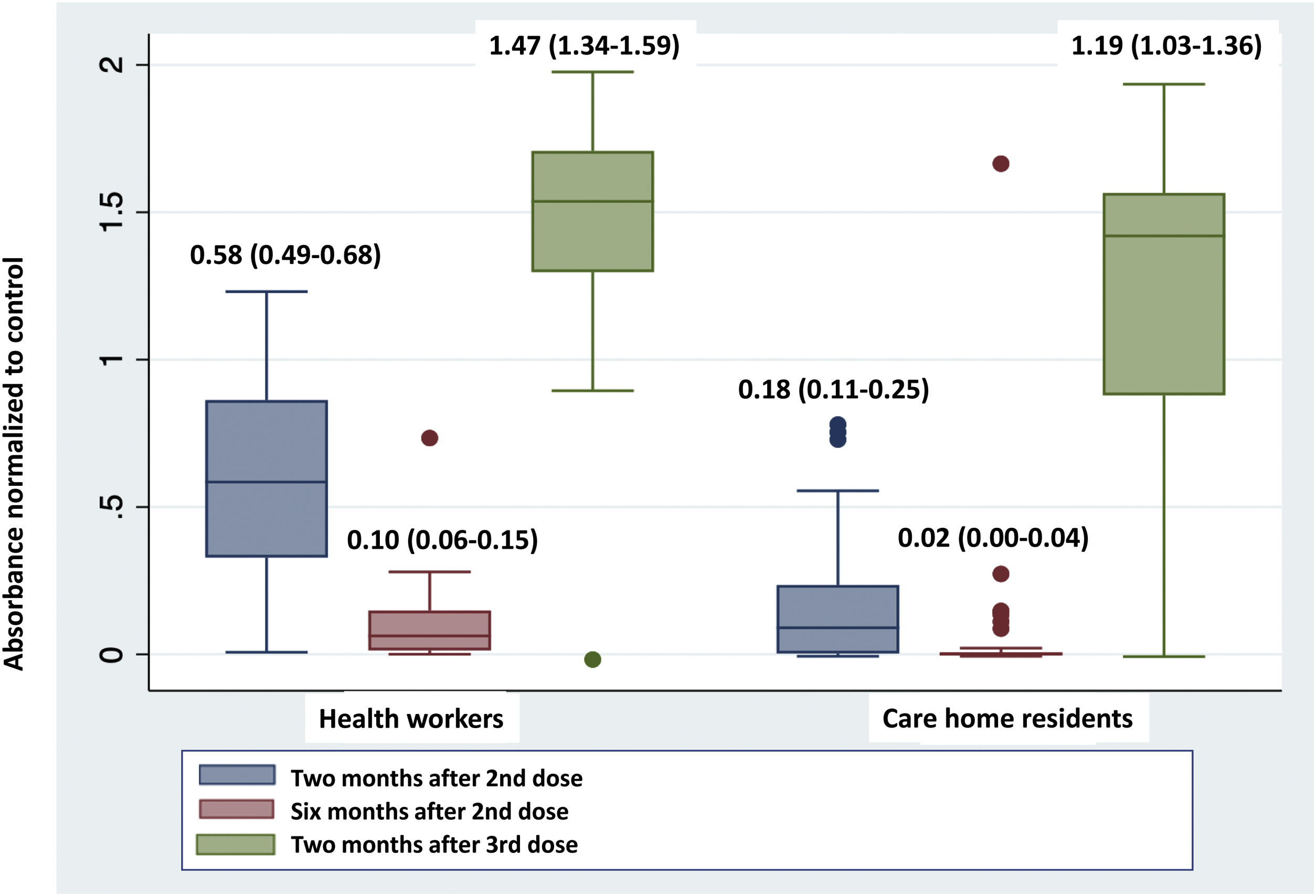

Fig. 1 shows a very significant reduction in absorbance in the determination of anti-S antibodies six months after the second dose of the vaccine compared to that obtained after two months, both in health workers and care home residents. The administration of the third dose produced a significant increase in this absorbance in the two groups, reaching the highest values of the series studied.

The comparison of the absorbance values at each of the moments studied between the two groups, health workers and care home residents, showed significant differences in the determinations taken two months after the second dose (0.58 [0.49–0.68] vs. 0.18 [0.11–0.25]; p<0.0001) and the third dose (1.47 [1.34–1.59] vs. 1.19 [1.03–1.36]; p=0.007), but not in the determination taken six months after the second dose (0.10 [0.06–0.15] vs. 0.02 [0.00–0.04]; p=0.36), with lower absorbance in care home residents than in health workers in all cases.

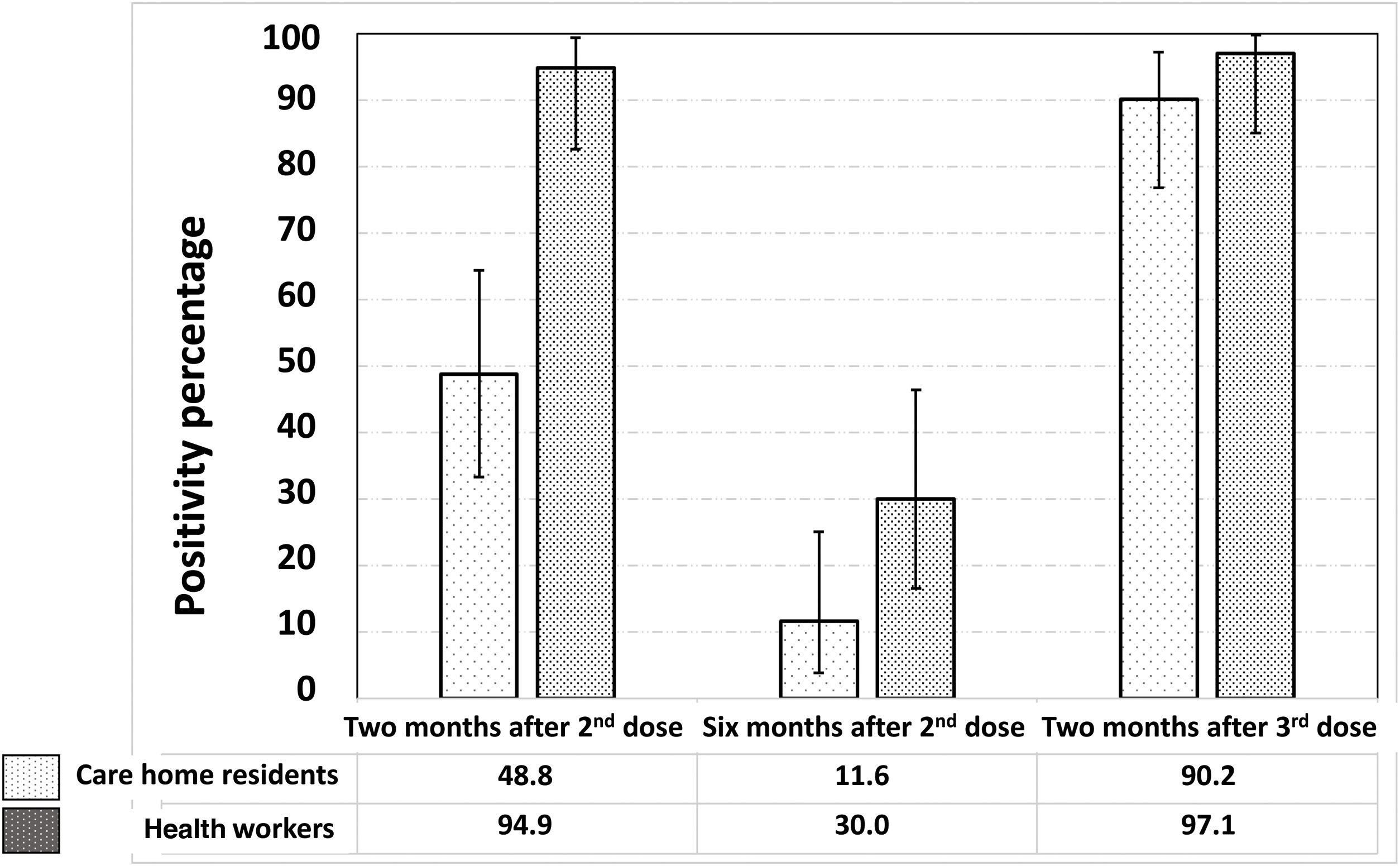

Fig. 2 shows the significant reduction in the prevalence of seropositives against the SARS-CoV-2 S protein six months after the second dose, as well as the increase, also significant, two months after receiving the third dose of the vaccine. The proportion of vaccine responders was lower among care home residents compared to health workers, both two months (48.8% [33.3–64.5] vs. 94.9% [82.7–99.4]; p<0.0001) and six months after the second dose (11.6% [3.9–25.1] vs. 30.0% [16.6–46.5]; p=0.04). However, two months after the third dose, no significant differences were observed between the two groups in the proportion of vaccine responders (90.2% [76.9–97.3] vs. 97.1% [85.1–99.9]; p=0.23).

DiscussionDetermining the efficacy of vaccines and the degree of protection they offer over time is key to national SARS-CoV-2 control strategies, making it easier to establish the need for booster doses and their timing.7 A decrease in the efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 has been observed, which, at least in part, may be due to progressive loss of vaccine immunity over time.7,8 Our findings demonstrate a significant reduction in the concentration of circulating antibodies six months after the second dose. We know that mRNA vaccines induce an early and potent humoral immune response that begins to decline within one month of vaccination, although circulating antibodies may persist and maintain their neutralizing effect for up to eight months after vaccination.9 The efficacy of vaccines in preventing severe cases and deaths remains at high levels even six months after vaccination, although studies show that decreasing antibody levels are associated with a higher rate of infections.10 As an example, among fully vaccinated health workers, the occurrence of new infections has been found to correlate with neutralizing antibody titers in the pre-infection period.11 The decrease found in our study was much sharper in care home residents than in health workers, a fact that is consistent with immunosenescence phenomena as shown by other authors.12 Another finding of our study was the rapid increase of circulating antibodies after the administration of a third dose, which is in line with other authors who have observed that, after the third dose, there is a rapid and important boosting of both cellular and humoral immunity, and a rapid restoration of the efficacy of the vaccine in terms of avoiding severe cases and even death.13 This effect was especially relevant in the case of patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared to those with a history, as if in some way the previous antibody levels limited the effect of the new booster.14

It should be noted that we have focused on subjects without a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and we have verified that there is no evidence of past infection by determining anti-N antibodies. As other authors have observed, the immune response after natural infection is more potent and durable than that induced by vaccines15 and, in addition, the response after vaccination is different in subjects who have passed the infection compared to those who have not. Vaccination is most effective in individuals with previous natural infection, who maintain higher and longer levels of anti-S antibodies.16

ConclusionsIn people not infected with SARS-CoV-2, vaccine-induced immunity declines over time, especially in those aged 65 and older. After a third dose, this immune response is significantly increased. The third dose is recommended for those vaccinated with two doses without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Ethical considerationsThe research was conducted in accordance with World Medical Association Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki). Participation was voluntary and an informed consent was obtained for all participants. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Drug Research (CEIM) of the León and Bierzo Health Areas (Ref. 2157; 03.30.2021).

FundingJunta de Castilla y León provides financial support through Consejería de Sanidad Project2020/00044/001.

Conflict of interestNone.

Bárbara Alonso and Sara Sánchez provided excellent technical assistance.