Editado por: Josep Maria Vilaseca - Althaia University Assistance Network of Manresa.

Antoni Dedeu - World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe

Violence against physicians is not a newly emerged but an increasingly serious problem. Various studies have reported a prevalence of up to 90%. If not prevented, it not only causes physical and mental harm to physicians who are dedicated to serving humanity but also affects the entire healthcare system and, consequently, the whole community with its direct and indirect effects. Some interventions have a positive outcome when effectively managed. However, for these interventions to be permanent and effective, they need to be multidisciplinary, legally backed and adopted as public policy. In this article, the prevalence of violence against physicians in the literature, its causes, practices worldwide, and suggestions for solving this problem are compiled.

La violencia contra los médicos no es un problema recién surgido, sino un problema cada vez más grave. Varios estudios han reportado una prevalencia de hasta el 90%. Si no se previene, no solo causa daños físicos y mentales a los médicos que se dedican a servir a la humanidad, sino que también afecta a todo el sistema de salud y, en consecuencia, a toda la comunidad con sus efectos directos e indirectos. Algunas intervenciones tienen un resultado positivo cuando se gestionan eficazmente. Sin embargo, para que estas intervenciones sean permanentes y efectivas, deben ser multidisciplinarias, contar con respaldo legal y adoptarse como política pública. En este artículo se recopila la prevalencia de la violencia contra los médicos en la literatura, sus causas, prácticas a nivel mundial y sugerencias para resolver este problema.

The World Report on Violence and Health (WRVH) prepared by the Violence Prevention Alliance (VPA), which is a group of many institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Federation of Red Crescent and Red Cross (IFRC) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), violence is defined as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation”.1

Currently, violence in the health field is a significant problem that is widespread, underreported and persistent. Based on the WHO data, approximately four out of every ten healthcare professionals (HCPs) are victims of physical violence at least once in their career.2 According to a meta-analysis, when verbal violence is also considered, 62% of HCPs are exposed to workplace violence.3

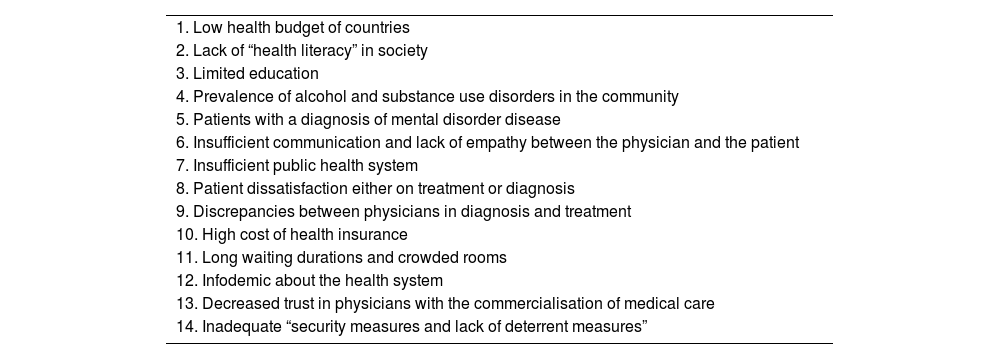

The triggersThe triggers of violence in healthcare are multifactorial4–6 and shown in Table 1.

Possible triggers of violence in healthcare.

| 1. Low health budget of countries |

| 2. Lack of “health literacy” in society |

| 3. Limited education |

| 4. Prevalence of alcohol and substance use disorders in the community |

| 5. Patients with a diagnosis of mental disorder disease |

| 6. Insufficient communication and lack of empathy between the physician and the patient |

| 7. Insufficient public health system |

| 8. Patient dissatisfaction either on treatment or diagnosis |

| 9. Discrepancies between physicians in diagnosis and treatment |

| 10. High cost of health insurance |

| 11. Long waiting durations and crowded rooms |

| 12. Infodemic about the health system |

| 13. Decreased trust in physicians with the commercialisation of medical care |

| 14. Inadequate “security measures and lack of deterrent measures” |

In most countries, physicians are seen as individuals of high economic status and are often thought to earn much more than they deserve. The influence of the media further increases this misperception. Accordingly, some resources consider violence against physicians a “class war”.7

For a better understanding of the causes and solutions of violence in health, it is also important to consider the perspective of patients. A study which aims to clarify patients’ thoughts about violence against HCPs and the relationship between these thoughts and aggressive behaviours was conducted with patients applying to family health centres (family doctor practices) in Turkey. According to the study, the most common reason for violence in health was reported as “patient attitude” (79.6%). The second most common reason was “lack of security” (27.6%). The risk of engaging in violent behaviour is 29 times higher among those who approve of violence, 8.8 times higher among those with psychiatric illness, and 8.2 times higher among those who do not attribute violence to illness. Although this research was not conducted with HCPs, 28.8% of the participants had witnessed violence in healthcare.8 According to physicians, the main reason behind the increasing violence is the changing health policies that frequently target physicians.5 In support of these findings, a study conducted with primary care physicians in Spain to determine the causes of violence against physicians showed that overcrowding in healthcare facilities and lack of communication between patients and physicians were the leading causes.9 In a Bulgarian study of patients and physicians, both groups reported that violence was a result of provoking behaviours.10

Current situation in the worldAccording to the World Medical Association, incidents of verbal and physical violence against physicians have increased significantly in recent years, regardless of the income and wealth levels of countries.6 Based on the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the health and social service sector experienced 7.8 incidents of serious violence per 10,000 workers. In comparison, all other major industries experienced less than two incidents per 10,000 workers.11

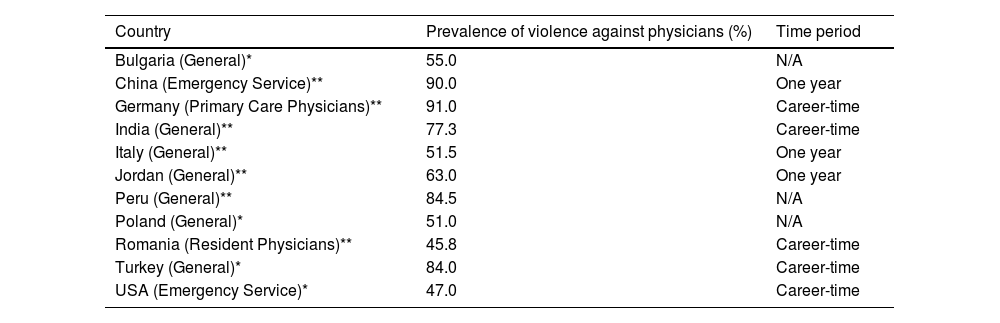

During September 2023, depending on only the news reflected in the press, one general surgery specialist was forcibly detained by armed people, one pregnant dermatology specialist was beaten in the abdomen, four family physicians and one nurse were beaten, a security guard died of a heart attack after a brawl, armed clashes occurred in the emergency room of two different hospitals, three young physicians from various specialities took their own lives in Turkey.12Table 2 shows the prevalence of verbal or physical violence against physicians reported in some countries.10,13–18

Reports and news on violence among physicians in some countries.6,10,13–18,20,54

| Country | Prevalence of violence against physicians (%) | Time period |

|---|---|---|

| Bulgaria (General)* | 55.0 | N/A |

| China (Emergency Service)** | 90.0 | One year |

| Germany (Primary Care Physicians)** | 91.0 | Career-time |

| India (General)** | 77.3 | Career-time |

| Italy (General)** | 51.5 | One year |

| Jordan (General)** | 63.0 | One year |

| Peru (General)** | 84.5 | N/A |

| Poland (General)* | 51.0 | N/A |

| Romania (Resident Physicians)** | 45.8 | Career-time |

| Turkey (General)* | 84.0 | Career-time |

| USA (Emergency Service)* | 47.0 | Career-time |

N/A: non-applicable.

In addition, in Canada, approximately 70% of emergency physicians reported an increase in violence in the last five years.19 Similarly, according to the American College of Emergency Physicians, almost half of emergency physicians have experienced physical violence, and 7 out of 10 physicians reported an increase in violence in the last five years.20 Along with the negative effects of this situation on physicians, violence affects the quality of patient care and causes financial losses in the health system.19

According to the “Report on Violence in Health” issued by the healthcare union with the most members in Turkey, there were 190 incidents of violence in 2021, which increased to 249 in 2022. Physicians are the most frequent victims of violence in the profession. Of the 494 aggressors who caused violent incidents during the year, 202 were not charged, and 141 were detained and released. Only 96 attackers were arrested, and legal proceedings were initiated against 53.21 However, these numbers are only the tip of the iceberg. It is known that physicians often do not report all incidents of violence against them because they believe that necessary measures will not be taken and reporting the cases will not change anything. There is also an acceptance that violence has become “part of the job”. A previous study found that only 50% of incidents of verbal abuse and less than 40% of physical assaults were reported.22 In a study conducted by the Turkish Medical Association, 69.7% of physicians stated that they did not report an incident of violence ‘because they knew reporting would not be effective’.23 According to the United States Department of Labour report, only 26% of physicians report an event of violence.24 Based on all this information, it is not accurately possible to reach real data, and physicians worldwide are violence victims more frequently than reported.6

One of the important reasons for violence is insufficient examination duration and dissatisfaction of patients due to this time slot.5 While the number of physicians per 100,000 inhabitants is 397 in European Union countries and 365 in OECD countries, this number is 217 in Turkey. While the number of applications per capita to primary care is 2.9, the number per capita to secondary and tertiary care is 5.1.25 What should be in the ideal system is the opposite of this situation. Patients who can be easily treated in primary care are being subjected to further tests and examinations in secondary and tertiary healthcare centres due to the nature of these centres and the effect of the defensive medicine approach, and this situation creates a vicious circle.

Individuals have difficulty finding an appointment due to the burden of secondary and tertiary care in Eastern European countries. Since the duration of the appointment they find with difficulty is limited, there is a general dissatisfaction among the patients even if the medical requirements are fulfilled during the examination. Similar problems are experienced in China. In a study conducted in China, 84% of physicians reported that patients were frequently referred to secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities for simple medical problems that could be solved in primary healthcare facilities.26 Also, in Bulgaria, only 5% of patients are satisfied with the healthcare system, mainly due to out-of-pocket payments and insufficient limits of the referral system.10 This challenge can be overcome by ensuring a referral system and strengthening the primary healthcare system. Primary healthcare is a cornerstone of the health system. Strong primary healthcare is the key to ensuring that society's health needs are met more effectively and everyone can receive healthcare services equally. More effective participation of primary care services in the health system will make health expenditures more cost-effective.27

The gender factor in exposure to violence has been frequently discussed in the literature, and the results vary according to the country where the study was conducted and the characteristics of the sample group, such as department. In a report on aggression against physicians in Spain, it was observed that gender was not a modifying factor in the incidence of aggressions.28 According to the results of a 20-year cohort study conducted by Noland et al. with Norwegian physicians, in the first years of the profession, male physicians were more likely to be exposed to violence, whereas no gender difference was observed after 15 years in the profession.29 In a study conducted by Tolhurst et al. with rural physicians in Australia, it was shown that men were more exposed to physical and verbal violence, while women were more exposed to harrasment.30

Healthcare studies indicate that emergency services and psychiatric units are the areas where violence is most prevalent. A comparative analysis examining violent events in primary and specialised care settings in one region of Spain over a year reported that one in four cases occurred in primary healthcare, with a higher rate of assault targeting doctors compared to other healthcare providers.31 A study in the Madrid region, analysing six years of records, similarly found that approximately one-third of the violent events occurred in primary healthcare settings. In both studies, verbal assaults were more common in primary care, while physical assaults were more frequent in specialised care settings.32

Most studies on violence against physicians have been conducted in Asian countries. In China and India, unlike Bulgaria and Turkey, a significant proportion of violence against physicians is not perpetrated by patients and their relatives. In China, intermediary groups called Yi Nao have emerged in health violence. The fact that people apply to these groups to receive compensation from physicians or hospitals has spread in many regions. In addition, these groups investigate possible malpractice cases and direct people.7

Potential threatsIn a survey conducted by the Croatian Physicians’ Association, 97% of physicians stated that the physical security in health institutions was not optimal and safety was not fully ensured.10 In a research published by the Turkish Medical Association (TMA), almost all of the physicians (93.4%) stated they were worried about being subjected to violence.23 A physician who is afraid of doing their duty will have an increased stress level, and their work performance will be affected. The physician may experience a lack of concentration, dissatisfaction with their job, emotional stress and exhaustion. As a natural consequence, they may make medical mistakes.33

As a result of motivational problems, physicians are looking for different ways out. One of these way-outs is for physicians to migrate to countries where violence against physicians is not as common as in their current country. The immigration of doctors is increasingly mentioned in the national and international presses.34 In 2022, a cross-sectional study of 9881 final-year medical students from 39 medical faculties in Turkey was conducted. According to the study results, approximately 70.7% of the students stated that they would like to continue their career abroad, while approximately 60% stated that they would like to live abroad permanently. The main reasons for this situation were the intensive workload on physicians, violence against physicians and increasing economic difficulties in the current conditions.35 Similar studies with medical students were conducted in other European countries. 84.7% of students in Romania, 39% in Lithuania and 62% in Poland stated that they planned to work abroad after graduation in the hope of better working conditions.36–38

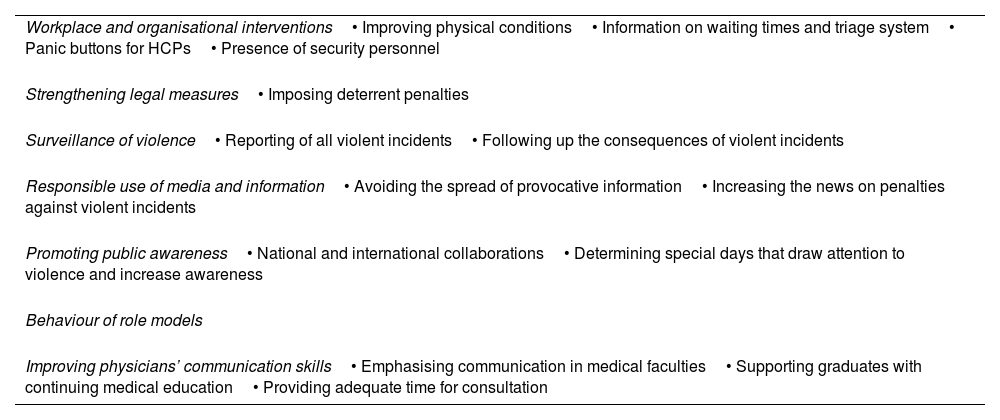

Actions to takeViolence is an important problem that should be condemned not only in the field of health but also in all fields. Unfortunately, violence against HCPs has become extreme today, and a multidisciplinary approach is required to prevent violence against physicians (Table 3). It is crucial to fully understand the extent and types of the problem to solve it. For this purpose, highly representative, multi-centre studies should be conducted by international institutions, associations or organisations using a standardised form.

Recommendations/actions to take to combat violence against doctors.

| Workplace and organisational interventions• Improving physical conditions• Information on waiting times and triage system• Panic buttons for HCPs• Presence of security personnel |

| Strengthening legal measures• Imposing deterrent penalties |

| Surveillance of violence• Reporting of all violent incidents• Following up the consequences of violent incidents |

| Responsible use of media and information• Avoiding the spread of provocative information• Increasing the news on penalties against violent incidents |

| Promoting public awareness• National and international collaborations• Determining special days that draw attention to violence and increase awareness |

| Behaviour of role models |

| Improving physicians’ communication skills• Emphasising communication in medical faculties• Supporting graduates with continuing medical education• Providing adequate time for consultation |

People's thoughts and behaviours about violence against physicians should be investigated, and precautions and action plans should be taken to address the causes.8 Representatives of physicians’ associations from 12 European countries convened in 2017 to discuss this issue and exchange experiences on approaches to management.10 European Medical Organisations, led by the Council of European Medical Orders (CEOM), adopted a declaration condemning violence against HCPs.39 Since 2019, “European Awareness Day on Violence against Doctors and Other Health Professionals” has been recognised on 12 March.40 More often, such international meetings with the participation of more countries and institutions will be effective in promoting public awareness about violence in health.

The media also plays a major role in this issue. Exaggerated and groundless news and provocative headlines that damage the trust in physicians of the society, who are unfamiliar with medical terms and conditions, should be avoided. Instead of news on violence, the media should cover the punishments received by offenders.41 It is also important that policymakers and people who are recognised as societal role models avoid discourses that target physicians. An important example of the impact of the media is the incident in China in 2012 in which a young physician was stabbed to death, and three physicians were injured. A magazine questioned the opinions of the public on this issue through an online survey. While 65% of the participants expressed satisfaction, those who felt anger were 14%, and those who felt sad were only 6.8%. Although the survey was removed in a short time, it caused further tension.42

Organisational measuresThere are measures to be taken to prevent the occurrence of violence in health, to minimise the damage to the victim during the incident, to prevent the reflection of the attack on other people in the environment and to prevent similar situations from happening again afterwards. To prevent the occurrence of incidents, firstly, the risk assessment should be made, potential weapons should be eliminated with advance warning systems, patients should be informed about waiting times, the public should be informed about the triage system, the presence of a sufficient number of security personnel should be clearly visible, no one should be alone in the working environment, and there should be deterrent laws. Healthcare workers should have the right to self-defence to reduce the damage during the incident. The use of panic buttons and the involvement of security personnel and the police during the incident are extremely important. All incidents of violence must be reported to prevent similar situations from happening again. Offenders who engage in aggressive behaviour must be followed up and prevented by legal means or, if necessary, by providing medical treatment and counselling.43 Similarly, The American Society of Emergency Physicians has recommended interventions such as increasing the number of security guards, using closed-circuit camera systems with 24-h observers, widespread panic buttons, and better control of emergency department entrances.44

Strengthening of legal measuresOne of the most crucial steps is to strengthen the law, but enforcement of the laws must be ensured. In a study on violence conducted by the Bulgarian Medical Association with patients and physicians, it was reported that both groups considered that the legal provisions were adequate but not adequately implemented. An analysis of Bulgaria's official records from 2014 to 2017 shows that only 4 out of approximately 175 incidents in the health field resulted in effective punishment.10 For example, in India, prevention of violence in healthcare laws in 19 states in the last ten years has been insufficient to solve the problem.4 However, in Spain, 20 April, the date on which a family physician was murdered, was declared the “National Day Against Aggression in Healthcare Facilities”, and a law was introduced to recognise attacks against doctors as crimes against the state. Violence incidents decreased by 16% in 2 years following the law, with a number of individuals receiving prison sentences.45 Similarly, in the USA, where 91 armed assaults against HCPs occurred between 2000 and 2011, laws were enacted in 30 states, making it a serious offence to attack HCPs.44 Singapore, recognised as one of the safest countries in the world, has adopted a zero-tolerance policy against attacks on healthcare workers. Under the Protection from Harassment Act, offences against healthcare workers while performing their duties are punished more severely with a fine of up to $5000, imprisonment for up to 12 months, or both. HCPs, especially front-line personnel, have been specially trained to mitigate and manage possible harassment and violence in the first place.46 Similar legal arrangements, including imprisonment and fines, have been made in Croatia, Slovenia, Romania and Bulgaria. In addition, in Slovenia, the patients’ rights law emphasises that patients should respect HCPs.10

In 2016, the Ministry of Health of Turkey initiated the implementation of Code White against incidents of violence like some other countries in the region. This includes all health workers to report any violence they are subjected to while on duty via landline or the internet. Crimes committed within the scope of Code White are investigated independently by judicial authorities, even if the victim of violence does not file a complaint.47 In 2022, the crime of intentional injury to a health worker was included in the catalogue crimes. Accordingly, “the offence of intentional injury committed against personnel working in health institutions during or because of their duties” is also included as a reason for detention. However, the laws are not a deterrent for individuals when we look at the incidents of violence that continue to increase yearly. In 2023, it was announced that an interim warning and pre-notification system would be developed before the white code with the joint work of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Interior. Furthermore, it aims to give a precursor code in case someone has previously committed violence.48 The feasibility and effectiveness of this system may be concluded in the future.

In the UK, doctors have the right to remove violent offenders from their list. The primary behaviours that justify immediate removal of a patient are assault, threatening behaviour and damage to property. In addition, violent patients are recorded, and this information is visible to other HCPs.49

Building up communicationEnhancing health literacy within the community and the widespread availability of medical information have led to an expansion in the range of topics discussed during patient–physician appointments. However, the constraints of limited examination durations pose a significant challenge. A literature review focused on communication skills training to manage patient aggression and violence in healthcare reveals that such training enhances the confidence of staff in handling aggressive situations.50 Effectively addressing this issue requires an improvement in the communication skills of physicians.51 To achieve this, it is essential to integrate more communication-related topics into the curricula of medical faculties. However, this alone may not suffice: a systematic review found that in the short and medium term, training given to healthcare professionals to prevent and minimise violence by patients was not effective in preventing violence compared to no training.52 The rapidly advancing landscape of technology is transforming communication dynamics, marking a departure from the conditions prevalent during physicians’ initial training. As a result, it is imperative for HCPs to stay current. Encouraging ongoing professional development (OPD) and/or continuing medical education (CME) activities for physicians after graduation would be valuable in addressing this evolving challenge.53

ConclusionViolence against physicians is a serious problem worldwide and is increasing day by day. For this reason, physicians have difficulty fulfilling their duties, are exhausted, migrate abroad or move to the private sector. As a result, it becomes challenging to maintain healthcare services in the public sector. Measures to prevent violence should be taken in a multidimensional manner, like improvement of regulations and law, focusing on communication skills of health professionals, working on health literacy of the populations, collaboration with patient organisations, good governance, a good role model government to the public in a sustainable way. Of course, the measures shall not be restricted to those mentioned only but search for other factors according to the regional needs by high-quality research. Given the long-term consequences, it should be considered by governments that not only physicians but the whole public will be harmed.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Authors’ contributionsThe authors alone are responsible for the content and the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit organisations.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.