Chronic eosinophilic airway inflammation, airflow limitation, and airway hyper-responsiveness are the mainstays of asthma diagnosis. The increased levels of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in asthma are closely related to the extent of airway inflammation. Sequential measurement of FeNO concentrations may accurately predict asthma severity and guide therapeutic decisions.

MethodsA total of 22,083 grade 1 students in Taipei city primary schools were screened for wheezing episodes using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire (ISAAC) questionnaires while their sero-atopic conditions were confirmed by Fluorescent Enzyme Immune Assay (FEIA). All students with allergies were tested by FeNO electrochemical test. 100 age-matched healthy students were used as control group (FeNO levels<25ppb).

ResultsFrom the 2650 students (12%) initially included via the wheezing criteria, 2065 (78.0%) were confirmed to have allergy by FEIA (sensitisation to at least two common aero-allergens in Taiwan) and diagnosed by a paediatric allergologist. Among them, 1852 (89.6%) had elevated FeNO values (>25ppb) and 266 (10%) had FeNO values<25ppb. Using the GINA guidelines, 140 mild-to-moderate asthma students who had received inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with or without Singulair treatment completed serial FeNO testing every three months for one year. The FeNO levels decreased in 121 students (86.4%) and increased in 19 students (13.6%), which was compatible to changing childhood asthma control score and response to step-down treatment, respectively.

ConclusionFeNO is an easy, used non-invasive tool for the diagnosis of allergic asthma. Sequential FeNO testing can accurately reflect asthma severity and provide for successful stepwise therapy for asthmatic children.

Airway eosinophilia is considered a critical event in the pathogenesis of asthma. Eotaxin and RANTES have been implicated in the allergic inflammation associated with asthma by promoting the migration and activation of inflammatory cells, including eosinophils. Concentrations of these cytokines in exhaled breath condensates (EBC) have been significantly correlated with exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) concentrations and serum eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) levels in asthmatics, particularly in unstable and steroid-naive stable asthmatics.1,2

Guidelines for asthma management suggest a stepwise approach to pharmacotherapy based on assessments of severity and control. However, the assessment of asthma control currently relies on surrogate measures like the frequency of symptoms or the frequency of use of short-acting β2-adrenergic agonists (SABA).3,4 Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and elevated FeNO levels are seen in asthmatic patients and have become increasingly recognised for their use in evaluating bronchial inflammation when monitoring anti-inflammatory treatment.5 Moreover, atopic individuals have increased FeNO levels, suggesting that atopy may be a co-determinant in FeNO production, although multivariate analysis has shown that atopy is not a significant predictor of FeNO levels in asthmatic patients.6

Exhaled nitric oxide has proven to be a marker of airway inflammation and has become a substantial part of clinical management of asthmatic in children due to its potential to predict possible exacerbation and for adjusting the dose of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).7 Measuring FeNO enables an easy and rapid assessment of airway inflammation such that there is now an international consensus on this testing methodology.8

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether sequential FeNO testing could accurately reflect asthma severity and provide for successful stepwise therapy for asthmatic children.

Materials and methodsA total of 22,083 first grade school children aged 6–7 years were included in this study. With the aid of their parents, current wheezing (within the last 12 months) was assessed using the ISAAC questionnaire. Sero-atopy was defined as a measurable specific IgE (≥0.35IU/ml) to any two of the common allergens tested in Taiwan: dust mites (der p, der f), blomia tropicalis, cat dander, dog dander, alternaria, and ragweed (Phadia ImmunoCAP system, Phadia AB, Sweden). Specific IgE tests were used for the students who met ISAAC wheezing criteria. The childhood asthma score was used to evaluate the pre-and post-treatment clinical features of the asthmatic children (cut off points: ≥21 controlled, =20 partly controlled, ≤19 uncontrolled, ≤12 very poor controlled). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Taipei City Hospital approved the study and all of the participants, their parents or guardians provided written informed consent.

A sequence of FeNO measurements (MINO device) once every three months for one year was made for children who were diagnosed by a paediatric allergologist as seroatopy positive. All of the study participants received maintenance ICS (Flixotide 50μg; 2 puffs) with or without Singulair (5mg orally per day) depending on their asthmatic condition.

A control group of 100 healthy students who met the exclusion criteria of no personal or family history of atopy, no history or symptoms of asthma and allergic rhinitis, never been diagnosed as asthmatic by a physician, and no corticosteroid or Singulair use in the last month also underwent FeNO measurements.

The above procedures used on patients and controls have been done after informed consent had been obtained.

ResultsA total of 22,083 grade 1 students were screened using the standardised ISAAC questionnaires to identify those who fulfilled the criteria for wheezing. Among the 279 students who met this criterion, 269 (96.4%) were sensitised to at least two common allergens in Taiwan and were diagnosed as asthmatic by a paediatric allergologist.

Among the 269 allergic asthmatic children, 241 (89.6%) had elevated FeNO levels (>20ppb) and 28 (10%) had decreased levels (<20ppb). A total of 140 students who received ICS with or without Singulair treatment completed the series of FeNO testing (Table 1). The FeNO levels decreased in 121 students (86.4%) and increased in 19 students (13.6%), which were correlated with the changing of C-CAT (≥20ppb, ≤19ppb).

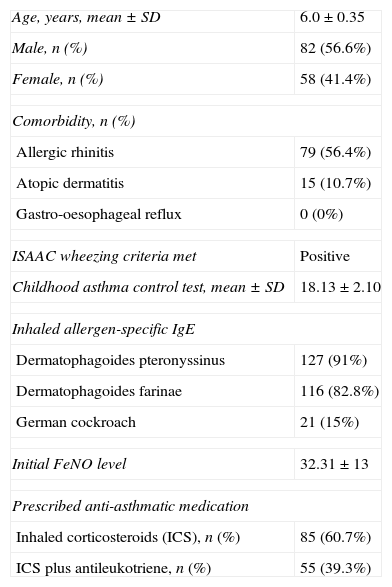

Characteristics of the study participants (n=140).

| Age, years, mean±SD | 6.0±0.35 |

| Male, n (%) | 82 (56.6%) |

| Female, n (%) | 58 (41.4%) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |

| Allergic rhinitis | 79 (56.4%) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 15 (10.7%) |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux | 0 (0%) |

| ISAAC wheezing criteria met | Positive |

| Childhood asthma control test, mean±SD | 18.13±2.10 |

| Inhaled allergen-specific IgE | |

| Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus | 127 (91%) |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 116 (82.8%) |

| German cockroach | 21 (15%) |

| Initial FeNO level | 32.31±13 |

| Prescribed anti-asthmatic medication | |

| Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), n (%) | 85 (60.7%) |

| ICS plus antileukotriene, n (%) | 55 (39.3%) |

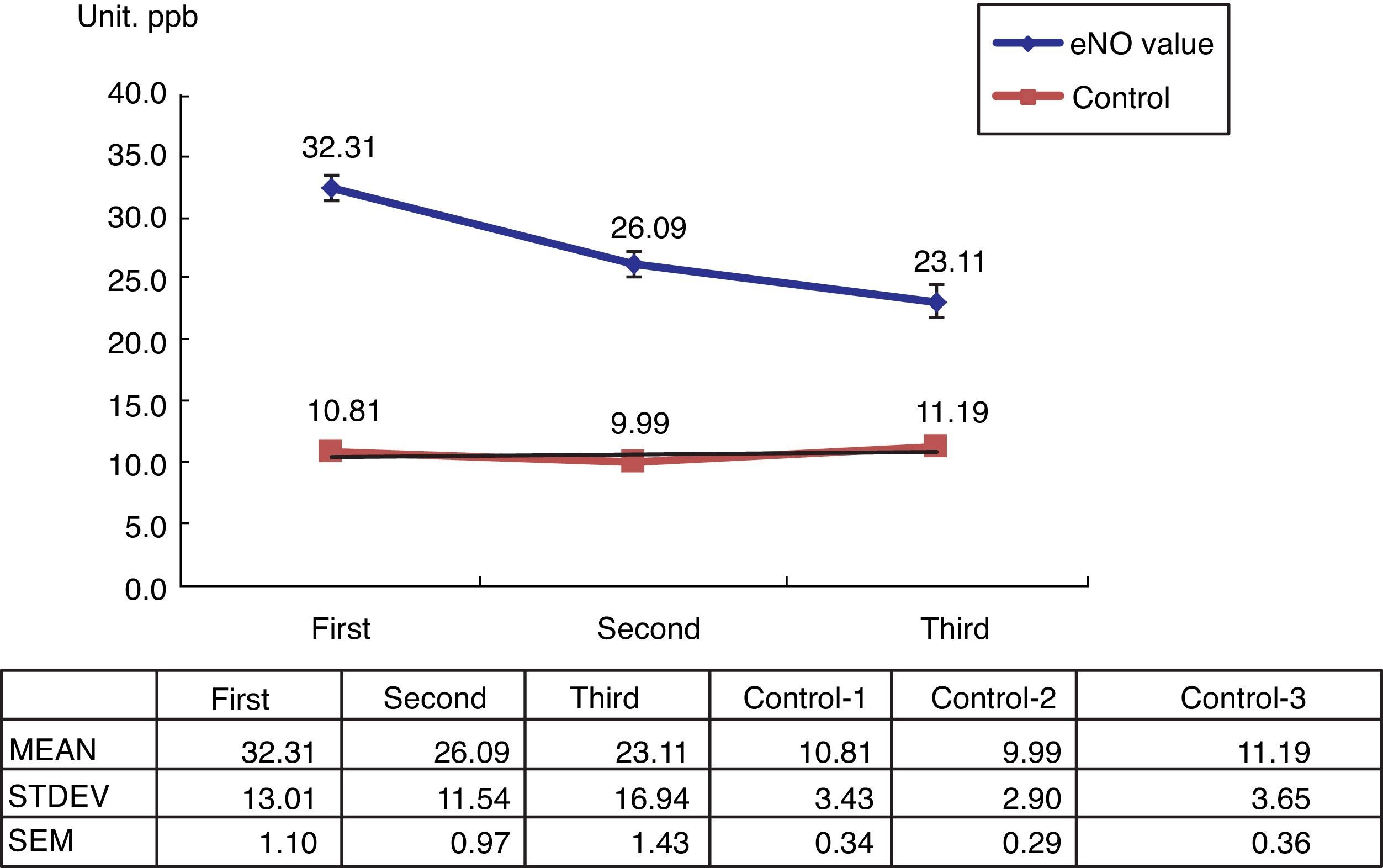

The 100 healthy students in the control group showed normal FeNO concentrations (<13ppb) (Fig. 1).

DiscussionExhaled nitric oxide has been used as a surrogate measurement to determine the extent of airway inflammation in mild to moderate asthma. However, whether FeNo levels reflect disease activity in symptomatic asthmatics receiving low dose ICS with or without Singulair is uncertain. In the present study, the ability of sequential FeNO determinations to reflect asthma control over time was investigated in a regular clinical setting.

In asthma, clinical symptoms and lung function are insensitive as regards reflecting the underlying airway inflammation. Monitoring this inflammatory process has only recently become available. FeNO is now recognised as a reliable surrogate marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation that offers the advantage of being completely non-invasive and very easy to obtain.9 Non-invasive markers are an attractive means for modifying therapy because they offer improved selection of active treatment based on an individual's response. Improved treatment titration using these markers is also better related to treatment outcomes.10

In addition, exercise-induced broncho-constriction (EIB) can be excluded with a 90% probability for asthmatic children with FeNO levels <20ppb without ICS treatment, and <12ppb for children with ICS treatment.11 For adult asthmatics, using a cut-off value of 40ppb has a 97% negative predictive value for a hand-held FeNO measurements (MINO) device.12,13 Another study showed that a cut-off of 32ppb of FeNO is a predictive factor for bronchial hyper-reactivity (BHR).8 For paediatric asthma, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for the best cut-off point (19ppb) are 80%, 92%, 89%, and 86%, respectively, which is similar to those of eosinophil percentage when using a 2.7% cut-off (81%, 92%, 89%, and 85%, respectively).14 Moreover, a cut-off point of 22.9ppb FeNO has the best predictive value for exacerbations, with an 80% sensitivity and 60% specificity for children.15 In another study, optimal clinical control of infantile wheeze may be associated with control of bronchial inflammation when evaluated by FeNO measurements (FeNO>15ppb).16

A key feature of FeNO in asthma therapy is that it can identify patients with difficult-to-treat asthma and the potential to respond to high doses of ICS or systemic steroids17 because eosinophilic airway inflammation contributes to persistent airflow limitation in severe asthma.18 In general, FeNO levels can be a clinically useful measurement of asthma severity and may be used as an adjunct to spirometry to determine appropriate treatment plans.4 One study shows that FeNO levels do not exhibit circadian rhythms, as subjects with nocturnal asthma have high FeNO levels both at night and during the day.19

Guidelines for asthma management suggest a stepwise pharmacotherapeutic approach based on assessments of asthma severity and control. FeNO analysis has been proposed as an easy tool for use in adjustments in asthma therapy.3 A recent study has shown significant independent relationships between higher FeNO levels and increasing SABA use and oral corticosteroid courses, confirmed by linear trend analyses. Thus, FeNO measurements may be a complementary tool to help clinicians assess asthma burden.20 Moreover, children who receive FeNO-guided treatment use prednisolone less often than children whose treatment is based on symptoms.21 FeNO can be used to identify sputum eosinophil counts ≥3% with reasonable accuracy, although thresholds vary according to ICS dose, smoking, and atopy.22

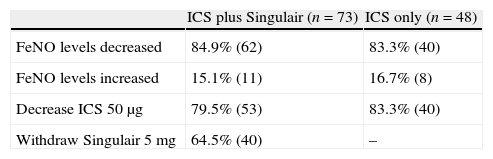

The present study shows that FeNO is a non-invasive tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of allergic-type asthma in children. Its positive predictive rate is about 89.6%, which is similar to other reports in literature. However, there is a 10% negative predictive rate. Using serial FeNO monitoring for the treated asthma children (n=140), FeNO levels (86.4%, n=121) continually decreased after the appropriate ICS with or without Singulair treatment (Fig. 1). This is comparable with the successfully reduced dosage of ICS and Singulair (ICS dosage from 50μg twice per day to 50μg daily in children with or without Singulair use, while Singulair 40 was withdrawn in 62 cases) (Table 2).

Results of inhaled corticosteroid with or without Singulair treatment in mild to moderate asthmatic primary schoolchildren with sequential exhaled nitric oxide monitoring.

| ICS plus Singulair (n=73) | ICS only (n=48) | |

| FeNO levels decreased | 84.9% (62) | 83.3% (40) |

| FeNO levels increased | 15.1% (11) | 16.7% (8) |

| Decrease ICS 50μg | 79.5% (53) | 83.3% (40) |

| Withdraw Singulair 5mg | 64.5% (40) | – |

Abbreviations: Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO); inhaled nitric oxide (ICS).

There are 19 students with increased FeNO concentrations, which may have been due to poor compliance to anti-inflammatory drugs, or from respiratory infections. Interestingly, the necessity for oral corticosteroid use for the group with decreased FeNO levels is less than that in the group with increased FeNO levels (49.5%, n=6 vs. 63.2%, n=12).

In conclusion, sequential FeNO monitoring is a simple, time- and resource-efficient tool for asthma control and for guiding optimal anti-inflammatory asthma therapy in children.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration. The authors confirmed the research meets ethical guidelines and it has been proved by the IRB of Taipei City Hospital.

Conflict of interestsThere are no conflicts of interest that may be inherent in their submission.