Biological agents such as cytokines, monoclonal antibodies and enzymes can cause allergic reactions, which may result in a wide range of clinical symptoms, from light pruritus to anaphylactic shock.1 Hypersensitivity reactions increase as exposure to biological agents increases.2 One biological agent that may cause a hypersensitivity reaction is recombinant human acid α-glucosidase (rhGAA). rhGAA is used to treat Pompe disease (PD),3 which is a rare, progressively debilitating, and often fatal lysosomal storage disorder. Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with rhGAA is shown to improve cardiomyopathy, motor skills, and functional independence, and to prolong survival in patients with PD.4 Other than rhGAA, there are currently no alternative treatments for PD.4 The present paper proposed a new desensitisation protocol that follows general desensitisation rules. The protocol was applied to the youngest patient with PD who developed anaphylaxis in response to rhGAA.

This seven-month-old female was born after an uneventful pregnancy. Her parents were first-degree cousins. The patient was diagnosed prenatally with PD after the death of her older brother from PD. Postnatal DNA sequence analysis of the GAA gene revealed homozygous c.1195-2A>G mutation which was previously shown to cause severe infantile PD.5 The cross-reactive immunological material (CRIM) status of the patient was determined by Western blot analysis and was found positive. The patient's brother was treated as a newborn at another medical centre for poor sucking, hypotonia, and cardiomegaly in 2005. He was diagnosed with PD following laboratory testing, including enzyme measurements and a muscle biopsy. The patient's brother died at eight months of age as a result of cardiopulmonary failure. Moreover, a cousin of the patient's father was also diagnosed with PD and died at four months of age. The patient's relatives were not treated with ERT because it was not available then. The female patient was started on the standard dose of rhGAA at another centre during her first month of life. During this period, the patient was asymptomatic; however, a low alglucosidase alfa level, high serum creatinine kinase level, and interventricular septal hypertrophy were noted. Anaphylactic shock developed after 15min in response to the twelfth ERT session. Widespread erythema on the ears, back, and chest were noted, as well as irritability and an intractable cough and stridor. A light erythema and generalised itching had been reported during the previous ERT session. Upon admission to our department, the patient's growth and physical examination were normal. Following echocardiographic examination, hypertrophy in the interventricular septum and mild tricuspid regurgitation was observed. The patient and the family had no history of atopy. Epidermal tests with rhGAA at concentrations of 1:1000 and 1:100 were negative five weeks after the anaphylaxis. Intradermal test with rhGAA at a concentration of 1:1000 was applied and was positive, with 6-mm×6-mm induration and surrounding hyperaemia. Therefore, we decided to treat the patient with desensitisation to rhGAA. We started the desensitisation protocol with half of the standard dose (i.e., 10mg/kg) as previously reported6,7 and gave this dose once a week instead of the standard recommended dose every two weeks (Table 1). Six different concentrations of rhGAA solution were prepared ranging from the stock solution of 5mg/ml to a saline-diluted concentration of 0.05μg/ml. A seventh concentration of 1mg/ml was also prepared from the stock solution. The initial dose was 1/1,000,000 of the therapeutic dose (1/1,000,000 of total dose: 80mg/1,000,000=0.08μg). This initial amount of enzyme with 0.05μg/ml concentration was calculated as 1.6ml. The doses were increased by half-log10 (∼threefold) increments8 every 20–30min. Therefore, the infusion rates were also increased by threefold every step. However, the concentration was increased every hour. The infusion set contained 25ml of fluid alone; therefore, 25ml more was prepared for each concentration (for example, to give 1.6ml in 30min, 27ml was prepared from the stock solution). For the next concentration, the remaining enzyme in the set was thrown and another infusion set was prepared for the consecutive concentration. The infusion rate was reduced to half steps when the patient developed generalised urticaria in the 9th and 10th steps during the initial two desensitisation weeks. During this time, the infusions were stopped and 2mg/kg diphenhydramine was given.

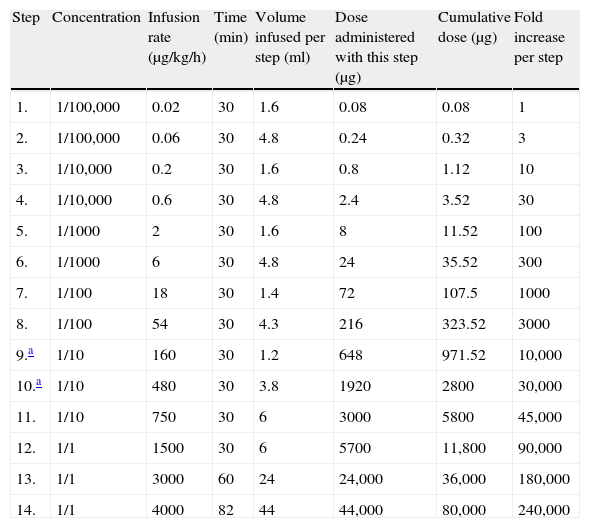

The first desensitisation protocol.

| Step | Concentration | Infusion rate (μg/kg/h) | Time (min) | Volume infused per step (ml) | Dose administered with this step (μg) | Cumulative dose (μg) | Fold increase per step |

| 1. | 1/100,000 | 0.02 | 30 | 1.6 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 1 |

| 2. | 1/100,000 | 0.06 | 30 | 4.8 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 3 |

| 3. | 1/10,000 | 0.2 | 30 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.12 | 10 |

| 4. | 1/10,000 | 0.6 | 30 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 3.52 | 30 |

| 5. | 1/1000 | 2 | 30 | 1.6 | 8 | 11.52 | 100 |

| 6. | 1/1000 | 6 | 30 | 4.8 | 24 | 35.52 | 300 |

| 7. | 1/100 | 18 | 30 | 1.4 | 72 | 107.5 | 1000 |

| 8. | 1/100 | 54 | 30 | 4.3 | 216 | 323.52 | 3000 |

| 9.a | 1/10 | 160 | 30 | 1.2 | 648 | 971.52 | 10,000 |

| 10.a | 1/10 | 480 | 30 | 3.8 | 1920 | 2800 | 30,000 |

| 11. | 1/10 | 750 | 30 | 6 | 3000 | 5800 | 45,000 |

| 12. | 1/1 | 1500 | 30 | 6 | 5700 | 11,800 | 90,000 |

| 13. | 1/1 | 3000 | 60 | 24 | 24,000 | 36,000 | 180,000 |

| 14. | 1/1 | 4000 | 82 | 44 | 44,000 | 80,000 | 240,000 |

Dose: 10mg/kg/day; the patient's weight: 8kg; total time: 8h and 22min; total volume: 110ml.

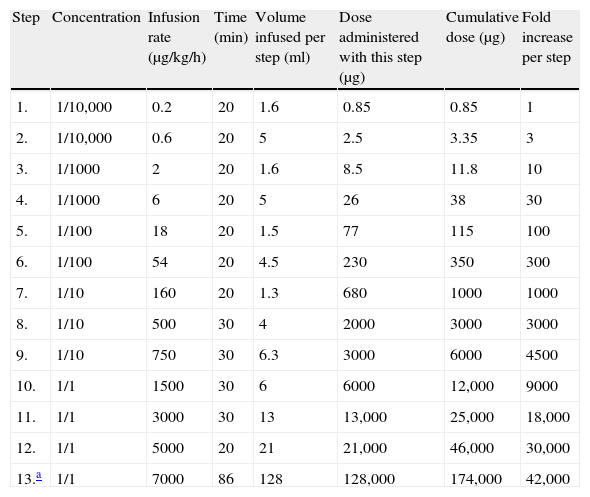

After two weeks, no infusion interruption was necessary. During the seventh week, the desensitisation protocol was conducted with the standard dose. Desensitisation was continued every two weeks after the eighth application. The patient received supervised rhGAA treatment for 4.5 months. Thereafter, the Paediatric Metabolism Unit continued to provide rhGAA, based on the protocol shown in Table 2. The patient showed normal growth and normal echo and electrocardiograms, and was able to perform age-appropriate activities at 22 months of age.

The final desensitisation protocol.

| Step | Concentration | Infusion rate (μg/kg/h) | Time (min) | Volume infused per step (ml) | Dose administered with this step (μg) | Cumulative dose (μg) | Fold increase per step |

| 1. | 1/10,000 | 0.2 | 20 | 1.6 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 1 |

| 2. | 1/10,000 | 0.6 | 20 | 5 | 2.5 | 3.35 | 3 |

| 3. | 1/1000 | 2 | 20 | 1.6 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 10 |

| 4. | 1/1000 | 6 | 20 | 5 | 26 | 38 | 30 |

| 5. | 1/100 | 18 | 20 | 1.5 | 77 | 115 | 100 |

| 6. | 1/100 | 54 | 20 | 4.5 | 230 | 350 | 300 |

| 7. | 1/10 | 160 | 20 | 1.3 | 680 | 1000 | 1000 |

| 8. | 1/10 | 500 | 30 | 4 | 2000 | 3000 | 3000 |

| 9. | 1/10 | 750 | 30 | 6.3 | 3000 | 6000 | 4500 |

| 10. | 1/1 | 1500 | 30 | 6 | 6000 | 12,000 | 9000 |

| 11. | 1/1 | 3000 | 30 | 13 | 13,000 | 25,000 | 18,000 |

| 12. | 1/1 | 5000 | 20 | 21 | 21,000 | 46,000 | 30,000 |

| 13.a | 1/1 | 7000 | 86 | 128 | 128,000 | 174,000 | 42,000 |

Dose: 20mg/kg/day; the patient's weight: 8.7kg; stock solution: 5mg/ml; total time: 6h and 6min; total volume: 195ml.

Currently there are no safe alternative treatments for PD; therefore, desensitisation is the only option for cases of anaphylaxis in response to rhGAA. The present paper details the only desensitisation protocol available for children in accordance with the general recommended rules.9 She is also the youngest patient with PD who is desensitised to rhGAA. To date there are only two published reports of desensitisation to rhGAA, one in an adult patient6 and the other in two children7 with PD. Although pharmacological desensitisation protocols are increasingly being used, guidelines have not been issued until recently. In 2010, the European Network of Drug Allergy (ENDA) and European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) interest groups on pharmacological hypersensitivity published consensus statements regarding the general considerations for desensitisation for drug hypersensitivity.9 In general, protocols should be applied to samples of more than 10 patients.9 Therefore, we wanted to use the proposed desensitisation protocol by El-Gharbawy et al.7 Even as allergists, however, we found the protocol complex and difficult to understand. The authors did not explain how they calculated the initial dose. Moreover, 10-fold increments were made during the initial steps of the desensitisation protocol. The authors named the steps as micro-dilutions, which they stated that resulted in significant reactions. Desensitisation protocols should rely on general rules and be simple, safe, easy to apply, and modifiable based on the patient's response.1,9 The initial dose for desensitisation was determined by taking into account the severity of the reaction. In general, it should be between 1/10,000 and 1/100 of the full therapeutic dose, unless anaphylaxis is severe. In that case, the initial dose should be between 1/1,000,000 and 1/10,000 of the full therapeutic dose.9 We preferred a concentration 1/1,000,000 as the initial dose because our patient had a history of severe laryngospasm. Moreover, breakthrough reactions are typically dose dependent and appear more frequently when the increments are excessive. Therefore, it is generally recommended to make two- or threefold increments.1,8,9 We chose threefold increments and modified this based on the patient's reaction. The desensitisation procedure was successful in our patient, and the target therapeutic dose was reached with clinical improvement without any significant adverse reactions.

Most patients with PD develop antibodies to ERT, depending upon their CRIM status. The majority of CRIM-positive patients have good therapeutic response to ERT; however, CRIM-negative patients almost consistently do not do well. This may be because they develop high-titre antibodies to rhGAA.10 Therefore, there is increasing interest in immune tolerance induction to ERT in CRIM-negative Pompe patients. Messinger et al.11 treated four CRIM-negative infants with PD patients either therapeutically or prophylactically with rituximab, methotrexate, and/or intravenous gammaglobulin. All patients experienced improvements in motor skills compared with the relentless downhill course of non-tolerant ERT-treated CRIM-negative patients. In another CRIM-negative infant with PD, a monoclonal IgE antibody (omalizumab) was successfully added to ERT after six months of treatment due to a severe IgE-mediated allergic reaction to rhGAA.12 The authors hypothesised that the anti-IgE antibody used for this patient halted additional allergic reactions and may have played an important role as an immune modulator. In contrast to these two reports, our patient was a CRIM positive PD patient. Her allergic reaction was a classic severe type I hypersensitivity reaction. In cases of anaphylaxis to medication, the consensus statements of the ENDA and EAACI interest groups recommend desensitisation with a related medication if there is no safe, effective alternative drug treatment.9

In conclusion, desensitisation is vital and inevitable for PD patients who develop anaphylaxis to rhGAA. The protocol that we propose here encompasses the general rules of desensitisation: a regimen that is safe, simple, and effective. Although desensitisation procedures have been conducted by different specialists, for the patient's safety, allergists should develop, review, and supervise treatments.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Patients’ data protectionThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patient mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.