A “nocebo” effect is defined as troublesome symptoms after the administration of placebo. The aim of this study was to determine characteristics of nocebo responses and related factors.

MethodsPatients with a reliable history of drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions subjected to placebo-controlled oral drug provocation tests and reacted to placebo, were consecutively included in this case–control study. Controls consisted of the randomly selected subjects who had a history of drug hypersensitivity reaction but did not react to placebo. A structured questionnaire was performed by an allergy specialist.

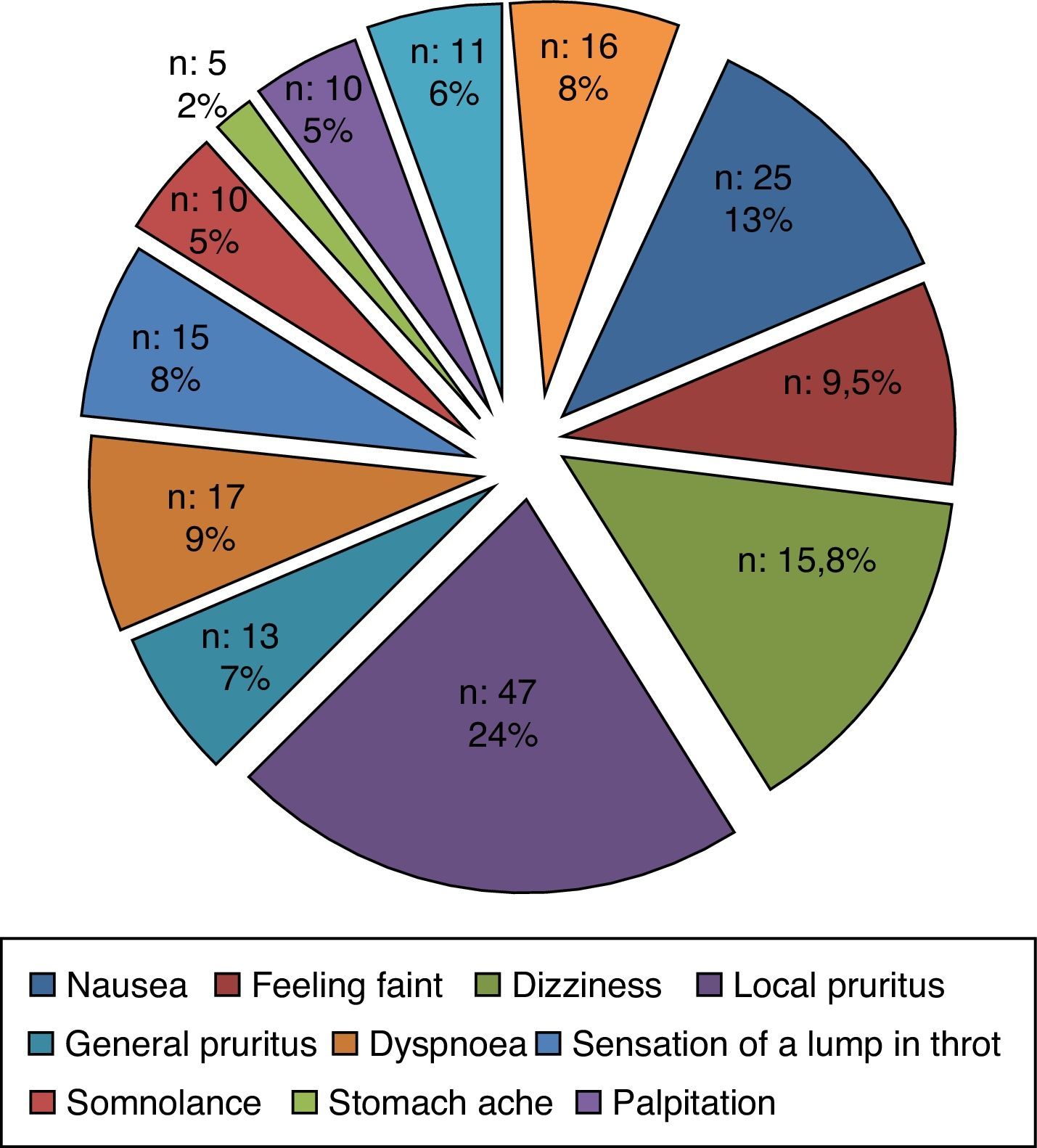

ResultsThere were 137 subjects (mean age: 43.10±12.65 years), with nocebo and 91 subjects (42.38±12.18 years) without any reaction to placebo. Most nocebo reactions (71.5%, n=98) were classified as subjective, with local pruritus as the most common finding. A minority of nocebo reactions (11.7%, n=16) were objective as cutaneous reactions including flushing and urticaria. Factors related with nocebo risks were university graduation (OR: 2.96, 95% CI: 1.27–6.93, p=0.012) and non-atopy (OR: 2.12, 95% CI: 1.02–4.40, p=0.043). In terms of the time of first and last historical reaction to drugs, each 1-unit (a month) increase in first reaction time (OR: 1.008, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02, p=0.001) and last reaction time (OR: 1.019, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03, p<0.001) were associated with increased nocebo risk.

ConclusionIn conclusion, subjects with high education, non-atopy, and older drug hypersensitivity reactions history seem to be more likely to experience nocebo effect during oral drug provocation tests. These risk factors should be considered and managed accordingly to complete the drug provocation procedure successfully.

The nocebo response or effect is defined as a negative and unpleasant response to the placebo, which is an inactive substance or a procedure.1 Nocebo was first defined in 1961 and since then more and more attention has been paid to this topic, because it is common, distressing, and results in wasted medication.2,3

Placebo-controlled oral challenge is an essential step in the management of drug allergy by aiming to find safe alternatives for patients with a history of drug-related hypersensitivity reactions. The procedure always involves blind administration of a placebo preceding administration of increasing doses of an alternative drug. In this context, it is obvious to differentiate bothersome symptoms provoked by placebo from those provoked by active drug. However, a limited number of studies have been focused on nocebo effect during placebo-controlled oral drug provocation tests in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to drugs.4,5 According to these studies the nocebo effect was common in drug allergy practice, but there was a lack of information regarding factors associated with nocebo effect in this group since there were no control subjects without placebo responses.

We have been performing single-blind placebo-controlled drug provocation tests in our university hospital for 15 years.6–8 By using this background experience, in this case–control prospective study, we aimed to assess the characteristics of nocebo effect and to document demographic and clinical factors affecting nocebo response among patients who underwent placebo-controlled oral provocation tests by comparing those who experienced or did not experience a negative response to placebo. Several factors associated with nocebo response in different clinical situations, none in drug allergy, have been defined previously.2,3 It will be helpful to determine the factors associated with nocebo response in patients with drug hypersensitivity reactions because this information will lead to good collaboration in advance between the attending physician and the patient who is candidate for drug provocation test in order to prevent unnecessary medical visits, waste of medications, and unnecessary alternative drugs.

MethodsSubjectsThe case–control study was carried out in a prospective manner in our allergy department located in a large tertiary clinic for adult patients in Ankara, Turkey. Between 2005 and 2012, 137 patients with a reliable history of drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions including urticaria, angio-oedema, generalised pruritus, rhinitis, acute bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema, and anaphylaxis who had been subjected to placebo-controlled oral drug provocation tests and had reacted to placebo with objective and or subjective symptoms were consecutively enrolled in the study.

After enrolment of nocebo cases, based on the statistical evaluation, 91 patients were selected as control group in order to reach a sample size of 228 which provides 75% power to detect an effect size (W) of 0.1752 using a 1 degree of freedom Chi-Square Test with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05000.9 The controls were randomly selected among patients who admitted to our department with a reliable history of drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction and subjected to placebo-controlled oral drug provocation tests but did not react to placebo challenge during 2012. Age–gender was matched to the nocebo subjects to account for potential confounding effects by age and gender.

The reliability of drug hypersensitivity was evaluated based on the patients’ detailed anamnesis and/or documentations from emergency care units, hospitalisation or involved physicians. Subjects with symptoms attributable to known side effects or severe non-immediate reactions such as Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), and Steven–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) were not included. Since drug provocation tests were part of the routine management, the patients were informed about the tests and a written signed informed consent was obtained prior to the challenges. The Ethical Committee of our faculty approves the oral challenge with placebo as part of the routine procedures.

Drug provocation testsDrug provocation tests were designed in a single-blind placebo-controlled oral drug challenge. The challenge protocol consisted of oral administration of the drug with increasing doses, as described in our previous studies.6–8 On two consecutive days, one and three fourths of divided doses of placebo and the active drugs were given at 1-h intervals. Active drugs were mainly antibiotics or analgesics that were tested for finding safe alternatives. Placebo challenge consisted of the controlled administration of the divided doses of placebo tablets or capsules (lactose) in similar dose intervals with the active drug. The challenges were performed at our outpatients’ clinic under continuous medical supervision and with emergency care equipment available. During the challenge procedure, blood pressure and FEV1 values as well as skin, ocular, nasal, and bronchial reactions were monitored every hour after each placebo or active drug dose was given. Patients were followed up to 24h to detect a delayed reaction for both placebo and active drug. In case of no reaction at the end of 24h, patients were regarded as placebo non-reactive or related drug tolerant.

QuestionnaireA face-to-face interview was performed by a specialist in clinical immunology and allergy. A specially designed questionnaire developed by the authors was used to evaluate nocebo effect among patients who reacted to placebo or not. The questionnaire consisted of questions about the patients’ demographics including age, gender, occupation, and educational status, family history of drug allergy, accompanying doctor diagnosed allergic or non-allergic diseases such as asthma, rhinitis, cardiovascular or gastrointestinal diseases, and psychiatric disorders. Additional items concerning clinical characteristics of previous drug reactions including time of first and last drug reaction before admission to hospital, the classes of the drugs involved in the reactions such as antibiotics, analgesics, local and general anaesthetics, muscle relaxants, radio contrast media, emergency room visit, and hospitalisation related with these reactions were also included. All these data were based on either the patients’ history and/or hospital or pharmacy file, and/or attending physicians. Nocebo responses were classified as subjective (e.g. sensation of dyspnoea, nausea, headache, itching, feelings of cold or warmth) and objective (vomiting, tachycardia, changes in blood pressure, skin rashes, wheezing). Symptoms of nocebo were closely observed by the attending physician and were determined as subjective, objective or a combination of both groups of reactions on the basis of physical examination and relevant laboratory testing.

Evaluation of atopyAtopy was defined as a positive skin prick. Skin prick tests were performed using a common panel, including Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, grass, tree, and weed pollens, cat, dog, Alternaria, Cladosporium, and cockroach allergen extracts (Stallergenes, Antony, France or ALK-Abello, Madrid, Spain). Positive and negative controls were histamine (10mg/mL) and phenolated glycerol saline, respectively. A mean wheal diameter of 3mm or greater than that obtained with control solution was considered positive.

Statistical analysisNumeric values were expressed as mean±SD, whereas categorical variables values were given as n Student's t-test was used to compare the two groups in terms of age. Chi-squared tests were used for comparison of two independent groups for categorical data. If the expected values for each category were higher than 5, Pearson Chi-Square value were used. If the expected values for each category were lower than 5, Fisher Exact Test or Monte Carlo simulation results were used. All directional p values were two-tailed and significance was assigned to values lower than 0.05. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used for evaluation of risk factors separately and together, respectively. The advantage of multivariate logistic regression is that it gives odds of each variable at the model purified from the effects of other variable (s) at the model. The odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS programme version 21 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsA total of 228 patients with a mean age of 43±12 year-old were enrolled in this study. There were 137 subjects (43.10±12.65 years), who experienced nocebo effect and 91 subjects (42.38±12.18 years) without any reaction to placebo during oral drug provocation test (Table 1). 70.3% (n=64) of the college graduated patients, 63.1% (n=41) of the high school graduated patients and 44.3% (n=31) of the primary school graduated patients reacted to placebo. There was a significant relation between high education level and nocebo effect (p=0.009).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with nocebo effect and no reaction to placebo.

| Nocebo effect | No placebo reaction | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, year | 43.10±12.65 | 42.38±12.18 | 0.43 | 0.67 |

| Nocebo effectn (%) | No placebo reactionn (%) | χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 117 (62.6%) | 70 (37.4%) | 2.66 | 0.103 |

| Male | 20 (48.8%) | 21 (51.2%) | ||

| Education | ||||

| College | 64 (70.3%) | 27 (29.7%) | 11.56 | 0.009 |

| High school | 41 (63.1%) | 24 (36.9%) | ||

| Primary school | 31 (44.3%) | 39 (55.7%) | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Housewife | 56 (58.9%) | 39 (41.1%) | 0.950 | |

| Working | 61 (59.8%) | 41 (40.2%) | ||

| Retired | 12 (63.2%) | 7 (36.8%) | ||

| Atopy | ||||

| + | 38 (58.5%) | 27 (41.5%) | 8.86 | 0.012 |

| − | 68 (70.1%) | 29 (29.9%) | ||

| Allergic diseases | ||||

| Asthma | ||||

| + | 39 (65%) | 21 (35%) | 0.81 | 0.365 |

| − | 98 (58.3%) | 70 (41.7%) | ||

| Rhinitis | ||||

| + | 23 (51.1%) | 22 (48.9%) | 1.88 | 0.170 |

| − | 114 (62.3%) | 69 (37.7%) | ||

| Urticaria–angio-oedema | ||||

| + | 17 (45.7%) | 19 (54.3%) | 4.14 | 0.126 |

| − | 120 (62.5%) | 72 (37.5%) | ||

| Other co-morbid diseases | ||||

| + | 62 (56.9%) | 47 (43.1%) | 0.89 | 0.344 |

| − | 75 (63%) | 44 (37%) | ||

| Psychiatric disorders in history | ||||

| + | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (46.4%) | 0.56 | 0.290 |

| − | 122 (61%) | 78 (39%) | ||

| Previous emergency department administration history with drug allergy | ||||

| + | 49 (55.1%) | 40 (44.9%) | 1.54 | 0.215 |

| − | 88 (63.3%) | 51 (36.7%) | ||

| Previous hospitalisation history with drug allergy | ||||

| + | 28 (59.6%) | 19 (40.4%) | 0.007 | 0.936 |

| − | 109 (60.2%) | 72 (39.8%) | ||

| Psychiatric consultation history | ||||

| + | 26 (56.5%) | 20 (43.5%) | 0.306 | 0.582 |

| − | 111 (61%) | 71 (39%) | ||

| Drug allergy history in family | ||||

| + | 20 (60.6%) | 13 (39.4%) | 0.004 | 0.948 |

| − | 117 (60%) | 78 (40%) | ||

| Previous antibiotic allergy history | ||||

| + | 72 (58.5%) | 51 (41.5%) | 0.21 | 0.646 |

| − | 64 (61.5%) | 40 (38.5%) | ||

| Previous analgesic allergy history | ||||

| + | 92 (62.6%) | 55 (37.4%) | 1.24 | 0.265 |

| − | 44 (55%) | 36 (45%) | ||

| Previous local anaesthetic allergy history | ||||

| + | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.93 | 0.490 |

| − | 132 (60.6%) | 86 (39.4%) | ||

| Previous general anaesthetic allergy history | ||||

| + | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) | 0.08 | 0.642 |

| − | 135 (60%) | 90 (40%) | ||

| Previous muscular relaxant allergy history | ||||

| + | 7 (53.8%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0.21 | 0.646 |

| − | 129 (60.3%) | 85 (39.7%) | ||

| Previous RCM allergy history | ||||

| + | 0 (0%) | 3 (100%) | 4.54 | 0.033 |

| − | 136 (60.7%) | 88 (39.3%) | ||

| Type of the previous allergic reaction to drugs | ||||

| Lower respiratory tract | ||||

| + | 12 (70.6%) | 5 (29.4%) | 0.92 | 0.335 |

| − | 122 (58.7%) | 86 (41.3%) | ||

| Upper respiratory tract | ||||

| + | 12 (46.2%) | 14 (53.8%) | 2.19 | 0.139 |

| − | 122 (61.3%) | 77 (38.7%) | ||

| Dermatological | ||||

| + | 66 (59.5%) | 45 (40.5%) | 0.001 | 0.977 |

| − | 68 (59.6%) | 46 (40.4%) | ||

| Dermatological+respiratory | ||||

| + | 29 (65.9%) | 15 (34.1%) | 0.91 | 0.338 |

| − | 105 (58%) | 76 (42%) | ||

| Systemic | ||||

| + | 37 (56.1%) | 29 (43.9%) | 0.47 | 0.491 |

| − | 97 (61%) | 62 (39%) | ||

RCM: radiocontrast media.

Among the patients with positive nocebo effect; almost half were non-atopic and relation between non-atopy and positive nocebo effect was statistically significant (p=0.012). In terms of allergic and other co-morbid diseases, there was no statistical significance between groups. The difference between nocebo group and no placebo reaction group according to first and last reaction time were statistically significant (p<0.001). Nocebo group had significantly higher first (121.74±106.102 vs. 62.90±85.701, p<0.001) and last reaction time (59.19±54.701 months, vs. 21.75±43.08 months, p<0.00) compared to no placebo reaction group.

In the univariate analysis, graduation from college, non-atopy, and newer drug reaction history appeared to be important risk factors associated with nocebo effects. In terms of the time of first and last historical reaction to drugs, each 1-unit (a month) increase in first reaction time and (OR: 0.993, 95% CI: 0.989–0.997, p<0.001), last reaction time (OR: 0.977, 95% CI: 0.966–0.987, p<0.001) were associated with decreased nocebo risk (Table 2).

Results from univariate regression analysis of factors related with nocebo effect.

| Variable | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | |||

| College vs. high school | 0.002 | 3.08 | 1.53–6.18 |

| College vs. primary school | 0.002 | 3.01 | 1.50–6.04 |

| Non-atopy | 0.047 | 2.07 | 1.01–4.24 |

| First reaction time | <0.001 | 0.993 | 0.989–0.997 |

| Last reaction time | <0.001 | 0.977 | 0.966–0.987 |

OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

All variables were evaluated by forward likelihood ratio selection method for multinomial logistic regression. Because of the statistically significant correlation between the first and last reaction time (r=0.535, p<0.001, two separate models were predicted. For the Model-1, when nocebo effect was evaluated according to education level, subjects who graduated from college as contrasted to subjects who graduated from primary school had 3.16 times more nocebo risk (OR: 3.16, 95% CI: 1.36–7.35, p=0.008). When the reaction risk to placebo between atopic patients and non-atopic patients were compared (OR 2.12, 95% CI: 1.02–4.40, p=0.043), as being non-atopic patient increases nocebo risk 2.12 times. In terms of the time of first historical reaction to drugs, each 1-unit increase in first reaction time (OR: 1.008, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02, p=0.001) was associated with increased nocebo risk.

For the Model-2, when nocebo effect was evaluated according to education level, subjects who graduated from college as contrasted to subjects who graduated from primary school had 2.96 times more nocebo risk (OR: 2.96, 95% CI: 1.27–6.93, p=0.012). In terms of the time of last historical reaction to drugs, each 1-unit increase in last reaction time (OR: 1.019, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03, p<0.001) was associated with increased nocebo risk.

A small number of nocebo reactions (11.7%, n=16) were classified as objective symptoms and findings and the most common objective findings were cutaneous including flushing and urticarial plaque (Fig. 1). The majority of the nocebo reactions (71.5%, n=98) were classified as subjective symptoms. Local pruritus was the most common subjective findings (Fig. 2). The remaining part of the patients (16.8%, n=23) described a combination of subjective and objective findings.

DiscussionIn the present study, non-atopy, high education level and older drug hypersensitivity reaction histories were found to be associated with nocebo effect during oral drug provocation.

Evaluation of the nocebo effect during placebo-controlled oral challenge in patients with adverse drug reactions has been the subjects of very limited studies. The first study reported that the overall occurrence of nocebo effect was 27% among 600 patients who had undergone a blind oral challenge with the administration of an indifferent substance and active drugs.4 As a single centre study which is the limitation of our trial, we worked with a smaller number of nocebo cases with a single blind manner. In the other study, the prevalence of nocebo effect was much less (3%) than previously reported.5 We did not target the prevalence of nocebo effect; instead we tried to define risk factors associated with nocebo effect. Female gender has been reported higher among nocebo responders.4,5,10 Additionally, elderly people have been reported to be more likely to experience nocebo effect.3 In our trial, gender and age were not significant variables affecting nocebo responses.

The nocebo effect could be influenced by several factors such as patient's expectation, experience, personal characteristics, psychological factors, and previous experience, and setting, subjective and objective conditions.2,11 The usual approach for drug provocation test is single-blind provocation test as we did in the present study. Patients were blind regarding whether they received placebo or active drug during oral provocation test and this approach may prevent negative expectations leading to nocebo response. Although data is lacking including our own experience, it would be interesting to see whether double-blind provocation test, both patients and physicians are blind, derives different data. Because of the previous experiences, patients with severe drug hypersensitivity reactions such as emergency visit or hospitalisation would have been expected to have an increased frequency of nocebo effect than those with mild previous drug reactions. However, this was not the case in our trial. Nevertheless, there was a relation between first and last drug reaction time interval and nocebo effect. This may be related with the effect of long time interval on patients memories related with historical reactions. It is obvious that patients with an old prior history will have difficulties to correctly remember and justify drug related unwanted effects leading to conditioning. Conditioned responses have also been reported in patients with asthma and other allergies.12–14 Allergic diseases in general were not associated with nocebo effect but atopy was a risk factor for nocebo effect. The other factor positively effecting nocebo response was graduation from college compared to high school or primary school, which may be associated with increased expectations or information generated response. It has been shown that placebo or nocebo responses may be generated by information about the effects of a drug, and well educated subjects will be more likely to receive information from different sources.1,15

It has been demonstrated that several psychological characteristics such as depression, anxiety, somatisation or generalised psychological distress predispose subjects to reporting non-specific side effects.3,6,16,17 We did not systematically evaluate personal characteristics of the all patients, but psychiatric consultations had been done for a number of patients and although depression was the most frequent diagnose, there were no differences between patients with or without nocebo effects in terms of psychiatric morbidity.

The nocebo response may be subjective (e.g. nausea, headache, itching, feelings of cold or warmth), but it may also be objective (vomiting, tachycardia, changes in blood pressure, skin rashes).2,4,5 In our study, subjective symptoms were predominant but we also observed some objective symptoms such as erythema, urticaria and cough that were mild and mostly transient and none of them severe enough to be treated.

Although many studies are available about nocebo effect, the mechanism underlying remains unclear and there is not enough knowledge on this topic in the medical education system. According to a survey in 2001, only a quarter of patients and nurses knew about nocebo effects.2,3,18 Since it is important to distinguish nocebo effect from drug-induced adverse reactions during oral provocation test, education and training of healthcare persons such as nurses and physicians on this topic, who are dealing with drug provocation tests, is clearly necessary.

In conclusion, subject with high education, non-atopy, and older drug hypersensitivity reactions history appeared to be more likely to experience nocebo effect during oral drug provocation tests. These risk factors should be considered and managed accordingly in order to complete the drug provocation procedure successfully.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare they have no financial or any conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Tuncer Değim who provided placebo tablets and capsules.