There are few studies which analyse the characteristics of allergic respiratory disease according to profiles of sensitisation to different allergens. This study describes the clinical features and therapeutic approaches, according to the sensitisation profile to relevant aeroallergens, in a sample of adult patients with a first-time diagnosis of respiratory allergy (rhinitis and/or asthma).

Methods1287 patients, enrolled consecutively in the spring of 2010 by 200 allergy specialists, were classified into four groups according to sensitisation to significant allergens in each geographical area (grass pollen, olive pollen, grass and olive pollen, house dust mites). Information was obtained on demographics, diagnostic procedures used, treatments prescribed, clinical characteristics of the rhinitis, and severity and control of asthma.

ResultsOf the patients, 58.6% had rhinitis only and 38.7% had both rhinitis and asthma. Patients with more severe rhinitis had more severe and poorer controlled asthma. Sensitisation to different allergens was not associated with significant differences in severity and control of asthma, but patients with house dust mite allergy presented persistent rhinitis more frequently. Allergy to grass pollen was significantly associated with food allergies. Differences were observed in the frequency of prescription of immunotherapy and antileukotrienes in patients allergic to house dust mites and of topical corticosteroids in patients with pollen allergy.

ConclusionsIt was observed in this study that in respiratory allergy disease, there are clinical differences as well as differences in diagnostic procedure and therapeutic attitudes, depending on the clinically relevant allergen.

The prevalence of allergic rhinitis in the general population in developed countries is high (10–42%),1 almost three times higher than that of asthma (4–10%).2 In Spain, rhinitis affects 22% of the population.3 The ARIA document (Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma)4 emphasises the reciprocal impact of the co-existence of allergic rhinitis and asthma. Up to 50% of patients with allergic rhinitis develop asthma, and over 75% of asthma patients have rhinitis.5 55% of patients who attend allergy clinics in Spain were diagnosed with allergic rhinitis, of whom 37% were also diagnosed with asthma.6 In addition, 89% of asthma patients seen by allergy specialists suffer allergic rhinitis.7

Allergy may be understood as a systemic disease which affects different organs,8 appearing in the form of rhinitis, frequently accompanied by conjunctivitis, and associated in many cases with asthma. The IgE-mediated allergic reaction to environmental allergens has been shown most conclusively to be the cause which sets this process in motion9,10 and it has been demonstrated that, at least for house dust mites, exposure and sensitisation follows a dose-dependent relationship.11 Furthermore, rhinitis and asthma are diseases of variable severity. Moreover, exposure to allergens may exacerbate symptoms of rhinitis and asthma in sensitised patients. However, there are very few studies which analyse the clinical characteristics of patients with allergic rhinitis and/or asthma related to the profile of sensitisation to various allergens in similar genetic and sociocultural populations.12,13 In China, sensitisation to Artemisia vulgaris or Ambrosia artemisifolia seemed to be associated with the severity of intermittent rhinitis, while sensitisation to house dust mites was associated with increased severity of asthma,14 but there are few data in western populations.

The rate of sensitisation in a population to a certain allergen is known to differ depending on parameters such as climate or environment. Around 80% of school children with asthma are sensitised to at least one of the common allergens in their environment, and sensitisation to a predominant allergen has been shown to increase the risk of suffering asthma 4 to 20-fold.13 In Spain, while grass pollen is the most significant allergen in the central and northern regions, olive pollen is the most significant in the southern half of the country and dust mites are predominant in the Mediterranean and island regions. The geographical variability of allergens may produce heterogeneity in terms of both prevalence and clinical manifestations.

The aim of this article is to compare clinical characteristics in patients with respiratory allergy, evaluating whether there are differences depending on their sensitisation profile to significant allergens in each geographical area of Spain, which might be translated into changes in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Accordingly, we present the data obtained on the clinical characteristics in a large sample of adult patients from all over Spain, with a first-time diagnosis of respiratory allergy (rhinitis and/or asthma) in allergy clinics, according to their profile of sensitisation. In addition, data on the diagnostic and therapeutic management of these patients are presented.

MethodsStudy design and variablesAn epidemiological, observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, multicentre study was designed, in which data were collected during a single visit from patients over 18 years of age with clinical manifestations of respiratory allergy. Each investigator had to enrol six consecutive patients diagnosed for the first time with rhinitis and/or asthma in an allergy clinic, according to the clinical criteria for rhinitis4 and asthma,15 and for patients with asthma, based on lung function testing.15 The patients were also classified into four groups according to their profile of sensitisation to significant allergens in each geographical area (establishing the exact relationship between the clinical picture and the symptomatic period): grass pollen, olive pollen, olive and grass pollens and house dust mites. Enrollment took place throughout spring 2010 (March to June), coinciding with the grass and olive pollen season in Spain. Patients also had to have been living for at least two years in the geographical area of the sample. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of centres by regions.

Patients sensitised to other perennial allergens, such as animal dander and moulds, occupational allergens and patients sensitised to other clinically significant pollens during the same pollen season in each region, and patients who had received prior immunotherapy or who had any other associated nasal or bronchial disease were also excluded. Participation in the study by investigators and patients was voluntary and patients had to sign informed consent. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic de Barcelona.

Sociodemographic (age, sex, smoking habit, and area of residence) and clinical variables were assessed for each patient. Data on the clinical characteristics of their rhinitis and asthma, diagnostic procedures used and prior treatment and treatment prescribed at the time of the visit were obtained. Allergic rhinitis was classified according to the criteria of the modified ARIA guidelines.16 The Spanish Guideline on the Management of Asthma (GEMA 2009)15 was used to assess the severity and degree of asthma control at the time of the consultation and control was also assessed using the Asthma Control Questionnaire ACQ5.17

Skin tests and determination of specific IgETo confirm the diagnosis of sensitisation to the most significant allergen (olive and grass pollen or house dust mites) in each geographical area, skin prick tests were carried out with or without determination of serum-specific IgE antibodies to these same allergens. Wheals with a mean diameter >3mm compared to the negative control (0.9% saline solution) were considered positive. Histamine (10mg/mL) was used as a positive control. A specific IgE value (InmunoCAP, Phadia, Sweden) >0.35kU/L for any determined allergen was considered positive.

Statistical analysisThe SAS statistical package version 9.1 was used and a descriptive statistical analysis was carried out. Categorical variables were described in terms of number and percentage of subjects in each category and continuous variables were expressed by mean, standard deviation, median, lower and upper quartiles and minimum and maximum values. No interpolation or extrapolation methods were used to assign missing data in any case. Associations between qualitative variables were analysed using contingency tables and the Chi-squared statistical test. Fisher's exact test was used for tables with very low values (n<5). For quantitative values, their association with factors such as the different allergens or the area of residence was studied using a T-test for two-level factors or the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for factors with more than two levels. When positive skin tests for both pollen and dust mites were obtained in the same patient (10.4%), the significant allergen was determined by the investigator according to the seasonal nature of symptoms, specific IgE determination or even specific allergen provocation testing. Statistical significance was declared if the p-value obtained was less than 0.05.

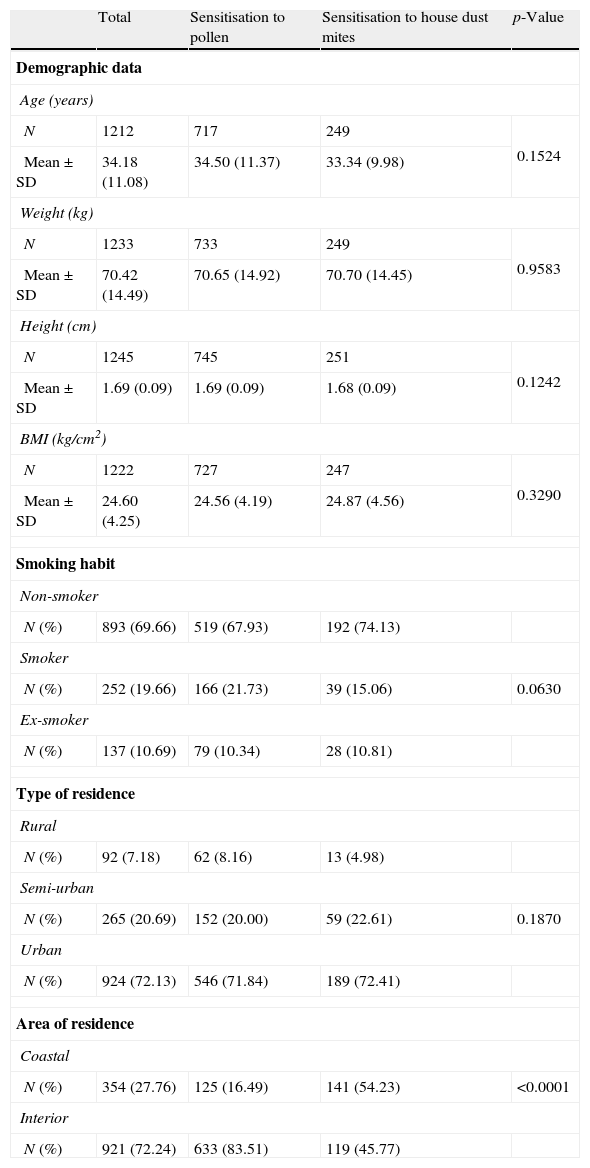

ResultsIn all, 200 allergy specialists participated in the study, located all over Spain. Of the 1437 patients enrolled, 150 were excluded because they did not meet all the inclusion criteria, leaving a total of 1287 patients for analysis. Sociodemographic data are presented in Table 1. Of the sample studied, 53.4% were female. Of the population analysed, 47% had a family history of atopy. A total of 736 patients (58.6%) was diagnosed with rhinitis and 487 (38.7%) had rhinitis and asthma, and this combination was more common in females (p<0.001). Only 2.63% of the subjects were diagnosed with asthma without concomitant rhinitis.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Total | Sensitisation to pollen | Sensitisation to house dust mites | p-Value | |

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| N | 1212 | 717 | 249 | 0.1524 |

| Mean±SD | 34.18 (11.08) | 34.50 (11.37) | 33.34 (9.98) | |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| N | 1233 | 733 | 249 | 0.9583 |

| Mean±SD | 70.42 (14.49) | 70.65 (14.92) | 70.70 (14.45) | |

| Height (cm) | ||||

| N | 1245 | 745 | 251 | 0.1242 |

| Mean±SD | 1.69 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.09) | 1.68 (0.09) | |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | ||||

| N | 1222 | 727 | 247 | 0.3290 |

| Mean±SD | 24.60 (4.25) | 24.56 (4.19) | 24.87 (4.56) | |

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Non-smoker | ||||

| N (%) | 893 (69.66) | 519 (67.93) | 192 (74.13) | |

| Smoker | ||||

| N (%) | 252 (19.66) | 166 (21.73) | 39 (15.06) | 0.0630 |

| Ex-smoker | ||||

| N (%) | 137 (10.69) | 79 (10.34) | 28 (10.81) | |

| Type of residence | ||||

| Rural | ||||

| N (%) | 92 (7.18) | 62 (8.16) | 13 (4.98) | |

| Semi-urban | ||||

| N (%) | 265 (20.69) | 152 (20.00) | 59 (22.61) | 0.1870 |

| Urban | ||||

| N (%) | 924 (72.13) | 546 (71.84) | 189 (72.41) | |

| Area of residence | ||||

| Coastal | ||||

| N (%) | 354 (27.76) | 125 (16.49) | 141 (54.23) | <0.0001 |

| Interior | ||||

| N (%) | 921 (72.24) | 633 (83.51) | 119 (45.77) | |

With regard to significant allergens, it was determined that the respiratory disease of 25.3% of the patients was caused by grass pollen sensitisation; olive pollen caused 7.8% and house dust mites 20.5%, while the remaining patients had clinically significant polysensitisation to grass and olive pollens. 19.9% of the patients had clinically significant coexisting sensitisation to both pollen and dust mites, so they were not included in the by allergen analysis.

Fig. 2 shows the percentages of patients with rhinitis and asthma and the group with the combination of both diseases. No significant relationship was observed between clinical diagnosis and the allergens evaluated in the study, but rhinitis was the most common disease both in patients sensitised to pollens and patients sensitised to dust mites. The mean time to development of rhinitis from the appearance of symptoms was 7.13 years (median 4.9) for rhinitis and 5.15 years (median 2.64) for asthma. However, when grass pollen was the causative agent for the respiratory allergy, the disease took longer to develop (p=0.015). Residence in a geographical area in the interior of the country was associated significantly with the development of respiratory allergy caused by pollen sensitisation, while residence in coastal areas was associated with dust mite respiratory allergy (p<0.0001).

Of the population studied, 67.3% had persistent rhinitis and the remaining 32.7% had intermittent rhinitis. It was observed that persistent rhinitis was more common in patients sensitised to dust mites than in patients with pollen sensitisation (p<0.01), although no differences were found in the degree of severity of rhinitis (Table 2) nor in the degree of severity and control of asthma in patients sensitised to the different significant allergens. Nevertheless, it could be shown among patients with both rhinitis and asthma, that the worse the severity of the rhinitis, the worse the severity and poorer the control of the asthma (Table 3).

Type and severity of rhinitis by sensitisation profile (according to modified ARIA 2008).

| Severity of rhinitis | p-Value | Type of rhinitis | p-Value | |||||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Intermittent | Persistent | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Pollen sensitisation | 112 | 15.62 | 502 | 70.01 | 103 | 14.37 | 0.5078 | 249 | 34.68 | 469 | 65.32 | 0.0042 |

| House dust mite sensitisation | 42 | 17.57 | 169 | 70.71 | 28 | 11.72 | 61 | 24.80 | 185 | 75.20 | ||

Relationship between severity of rhinitis by severity of asthma and asthma control in patients with both diseases.

| Asthma by severity | p-Value* | ||||||||

| Intermittent | Mild persistent | Moderate persistent | Severe persistent | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| (A) Severity of rhinitis by severity of asthma in patients with both diseases | |||||||||

| Rhinitis by severity | |||||||||

| Mild | 29 | 40.85 | 30 | 42.25 | 11 | 15.49 | 1 | 1.41 | <0.0001 |

| Moderate | 86 | 29.55 | 91 | 31.27 | 112 | 38.49 | 2 | 0.69 | |

| Severe | 14 | 22.95 | 14 | 22.95 | 27 | 44.26 | 6 | 9.84 | |

| Asthma by control | p-Value* | ||||||

| Good control | Partial control | Poor control | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| (B) Severity of rhinitis by asthma control in patients with both diseases | |||||||

| Rhinitis by severity | |||||||

| Mild | 44 | 58.67 | 25 | 33.33 | 6 | 8.00 | <0.0001 |

| Moderate | 123 | 37.61 | 166 | 50.76 | 38 | 11.62 | |

| Severe | 14 | 21.21 | 35 | 53.03 | 17 | 25.76 | |

The analysis of associated diseases showed that 76% of all patients had concomitant allergic conjunctivitis, and this was significantly more frequent among the population with pollen sensitisation, compared to those with dust mite sensitisation (82.7% vs 53.3%; p<0.001). The rate of conjunctivitis was significantly higher in patients with rhinitis who resided in the interior of the country compared to coastal residents (p=0.016). The presence of food allergy was associated more frequently with allergy to either of the pollens studied (11.1% for grass pollen sensitisation; 11.7% for olive pollen and 12.4% for joint grass-olive sensitisation; p<0.05), compared to 8.1% in patients with house dust mite sensitisation, while the presence of atopic dermatitis was associated only with grass pollen sensitisation (13.5%; p=0.01).

With regard to diagnostic procedures, all patients were given skin prick tests. Only 55.3% of patients with allergic rhinitis had anterior rhinoscopy. There was a clear difference in the diagnostic orientation according to the sensitisation profile. The use of diagnostic tests such as anterior rhinoscopy, fibre endoscopy, computed axial tomography of the paranasal sinuses, total and specific serum IgE determination and evaluation of nasal obstruction were carried out more frequently in patients with house dust mite sensitisation than in patients sensitised to pollen. In addition, there were differences in the resources used in the diagnosis of asthma, with significantly more patients with dust mite allergy undergoing the bronchial hyperreactivity test, exhaled nitric oxide test and sputum eosinophil counts. In contrast, molecular diagnosis of allergenic components was used more in patients with rhinitis and/or asthma sensitised to pollen.

Finally, no differences were observed in the therapeutic management of patients according to their sensitisation profile (Table 4), except for patients with dust mite allergy in whom the most common treatment was antileukotrienes for asthma (28.9% vs 18.7%) and immunotherapy for rhinitis (41.3% vs 30.5%). In contrast, in the group of patients with pollen allergy, the use of the combination of glucocorticoids and long-action beta-2 agonists was more common in asthmatics (73.1% vs 61.7%) and the use of topical corticosteroids for rhinitis was more common (88.0% vs 74.1%; p<0.0001).

Prescribed treatment for rhinitis and asthma according to aeroallergen sensitisation.

| Pollen sensitisation | Dust mite sensitisation | p-Value* | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| (A) Treatment prescribed for rhinitis by sensitisation type | |||||

| Antihistamines | 696 | 95.74 | 220 | 89.07 | 0.0003 |

| Antileukotrienes | 36 | 4.95 | 19 | 7.69 | 0.1121 |

| Topical nasal corticosteroids | 640 | 88.03 | 183 | 74.09 | <0.0001 |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 16 | 2.20 | 7 | 2.83 | 0.6276 |

| Topical nasal decongestants | 12 | 1.65 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.2030 |

| Immunotherapy | 222 | 30.54 | 102 | 41.30 | 0.0023 |

| (B) Treatment prescribed for asthma by sensitisation type | |||||

| Short-action beta-adrenergic agonist | 167 | 56.80 | 58 | 54.21 | 0.6508 |

| Antileukotriene | 55 | 18.71 | 31 | 28.97 | 0.0384 |

| Inhaled glucocorticoid | 38 | 12.93 | 9 | 8.41 | 0.2917 |

| Inhaled glucocorticoid+long-action beta-adrenergic agonist | 215 | 73.13 | 66 | 61.68 | 0.0357 |

| Immunotherapy | 109 | 37.07 | 32 | 29.91 | 0.1953 |

| Omalizumab | 2 | 0.68 | 4 | 3.74 | 0.0459 |

| Other | 6 | 2.04 | 2 | 1.87 | 1.0000 |

In Spain, allergic rhinitis is the main reason for specialist consultations in Allergy Departments,5 and this was reflected in our study of over 1000 patients. Classically, rhinitis has been classified according to whether its presentation was continuous throughout the year (perennial) or limited to certain periods (seasonal), and an attempt was made to establish an aetiological relationship with exposure to different aeroallergens. However, the ARIA classification allows a more standardised evaluation of allergic rhinitis, taking into consideration both the duration and the severity of symptoms, which makes it easier to compare the results of the various epidemiological studies and introduces more homogeneity into clinical practice. In this respect, although our figures are slightly lower than those reported in other studies,18 67.3% of our study patients had persistent rhinitis, but only 20.5% had house dust mite sensitisation as the significant allergen, showing that the two classifications are not superimposable. However, this datum may be biased because the mildest cases of pollen allergy do not attend specialist clinics and because the period of inclusion of patients in our study was during spring. Indeed, in studies in the general population, the prevalence of persistent rhinitis in subjects with a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis scarcely reached 29%.3 In addition, the fact of suffering persistent rhinitis is determinant when it comes to therapeutic approach, since, according to the ARIA guidelines,4 in this study a greater use of topical corticosteroids is observed in the moderate and severe forms of the disease. However, although patients with dust mite sensitisation have persistent rhinitis more frequently than those with pollen sensitisation, this latter group is more frequently prescribed antihistamines, and, curiously, a greater amount of topical nasal corticosteroids. In contrast, the use of specific immunotherapy is more extended in patients with dust mite sensitisation, possibly in accordance with the immunotherapy guidelines,19 since these patients frequently have persistent rhinitis.

The correlation of concomitant diseases with respiratory allergy reveals that conjunctivitis is significantly associated with all the sensitisations studied, as could be expected due to the high degree of association between the two,20 although it is notable that the correlation was significantly less in patients with dust mite allergy. However, the frequent combination of rhinitis and asthma in this study, in up to 38% of cases, is remarkable, and reinforces the “one airway, one disease” concept.21 This combination was more common in women, but, while the female sex has been associated with a higher incidence of asthma,22 this fact is not clearly demonstrated.

In the study, there are no clinical differences between the different allergens, except in the time of development of the disease, which is greater in patients with grass pollen allergy. This may be explained by a lower demand for consultations in patients exposed to allergens for only a few months, while the patient with a dust mite allergy, whose exposure is more constant, would develop more persistent and intense symptoms, resulting in an earlier demand for a consultation with the allergist.

It is worth pointing out the association between pollen sensitisation and food allergy. Proteins such as profilins, present in the pollens, which act as panallergens would explain the higher rates of co-sensitisation between pollens and foodstuffs reflected in this study. Sensitisation to profilin would be produced by the respiratory route on inhalation of the pollen, and oral symptoms would then be produced after the exposure to the profilin in vegetable foodstuffs.23 In addition, it is interesting to see the greater incidence of sensitisation to profilin in the Spanish population, which is higher than that published in other series,24 possibly due to a high rate of grass pollen sensitisation, although its significance in the clinic is unknown.25 In this respect, our study reflects the more frequent use of molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of respiratory allergy caused by pollens, a tool which has been recently adopted for specifying the allergens which are really involved.26 In contrast, in patients allergic to dust mites, although a crossover reactivity with seafood by the topomyosin route, among others, has been described,27 no higher prevalence of food allergy was observed in this study.

To summarise, although asthma and allergic rhinitis are different forms of the same disease, there are few studies analysing the characteristics of the disease on the basis of the profile of sensitisation to different allergens. In the present study, it can be seen that different clinical pictures, different diagnostic procedures and even different therapeutic approaches exist, depending on the relevant allergen involved in the development of the respiratory allergic disease, namely dust mites compared to grass or olive pollen.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionConfidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchProtection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Financial supportThis study has been partially supported by Laboratorios ESTEVE.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare no conflict of interest for this study.