Assessment of demographic and clinical factors that have an impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients with asthma in Spain.

Patients and methodsMulticenter, prospective, observational, cohort study, conducted in 40 Spanish Pneumology Units during a 12-month period. Data on sociodemographic, clinical variables, asthma treatment and QoL were collected in a case report form.

Results536 patients (64.6% women, mean age: 54) were recruited. Reported QoL was better for patients from Northern and Central Spain as compared with those from the South and the East (p<0.001), students and employed patients as compared with housewives and unemployed (p<0.01), for those who had received asthma information (p<0.01), for those with milder daytime symptoms (p<0.01) and for patients with higher level of education (p<0.05).

ConclusionsAmong the factors that have a significant effect on patients’ QoL only symptom control and patient education on asthma control are modifiable. Therefore, all the strategies should be tailored to improve such factors when managing asthma patients.

Asthma is a global health problem that affects around 300 million individuals of all ages, ethnic groups, and countries. It is estimated that 250,000 people die prematurely each year as a result of asthma.1 In Spain, asthma prevalence ranges from 4.9% to 14.6% when the diagnostic criteria is based solely on the presence of symptoms indicative of disease, and from 2.4% to 4.7% when the presence of bronchial hyper-response is included for diagnosing.2–5

The pathogenesis of asthma involves the interplay of biological, social, and psychological factors.6,7 Both educational and psychological interventions as a supplemental tool can help the pharmacologic management of asthma, although such interventions are often considered difficult to implement in daily clinical practice.8

In recent years we have seen an increased prevalence of asthma in the western world, with consequent rising burdens on health-related costs.9,10 One action taken to deal with this problem has been to educate patients about their disease in order to promote self-management. Thus, asthma management studies have been shown to reduce the number of hospital admissions, days off work due to asthma exacerbations and improve symptom scores and inhalation techniques.11–21 However, limited knowledge is currently available on the impact of different demographic and clinical factors on health-related quality of life (QoL).8,13,17,22

ASMACOST is an observational study whose main objective was to estimate the economic costs of the management of adult asthma patients in the context of daily clinical practice in Spain.23 In addition among secondary aims included the assessment of demographic and clinical factors that have an impact on the QoL of patients with asthma in Spain.

Patients and methodsStudy designASMACOST was a multicenter, prospective, observational, cohort study, conducted in 40 Spanish Pneumology Units. During the 12-month period of the study, 3 visits were scheduled at 0, 6 and 12 months, and data on sociodemographic, clinical variables, asthma treatment and quality of life were collected in a case report form.

Patients were required to give written informed consent before inclusion in the study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of General Hospital of Vic (Barcelona, Spain), and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study populationPatient inclusion criteriaAdults patients diagnosed of asthma according to GINA criteria and adapted to the Spanish Asthma Management Guidelines, were included in the study.24,25 Other inclusion criteria included the presence of stable disease (no exacerbations within the last four weeks that have required a change in treatment, that is, use of beta agonist whenever needed); absence of any physical, psychical or language limitation that prevented the correct completion of the case report form.

Patients’ sample was stratified according to the following variables: severity of asthma disease: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent; severe persistent; age group: 18–65 years; >65 years; geographical area: North (Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, País Vasco and Navarra), East (Cataluña, Comunidad Valenciana, Baleares), Central (Rioja, Aragón, Castilla-León, Madrid, Castilla La Mancha), South (Andalucía, Extremadura, Canarias, Ceuta, Melilla).

VariablesPhysician-reportedAmong the clinical variables included: disease severity according to GEMA 2009 criteria (intermittent; mild persistent; moderate persistent and severe persistent)25,27; year since diagnosis; lung function [forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) <60%; between 60% and 80% and >80%]; severity of diurnal and nocturnal symptoms and concomitant diseases.

Patient-reportedSocio-demographic data: Age, gender; educational level, job status and geographical distribution (regional location, habitat, size).

Asthma control information: Information received about asthma; participation in an asthma educational plan; asthma self-management.

Self-estimated health status question: Instrument that categorizes the responses using the Likert scale, from 1 (very good health) to 7 (very poor health).

QoL measurements: European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D): Visual Analogue Scale (VAS); Juniper Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (Mini-AQLQ)26: it is a validated 15-question, self-administered instrument where the questions are grouped into four domains: activity limitations (4 items), symptoms (5 items), emotional functions (3 items) and environmental stimuli (3 items). The questions are scored on a scale of 1–7 (where 1 is greatest impairment and 7 is least impairment) and grouped in a global score.

Sample size: The implementation of a stratified sampling, with a total of 32 strata and 35 patients per stratum, required a total sample of 1120 patients, with an expected follow up loss of 20%.27,28

Statistical analysis: For the description of continuous variables, the mean and standard deviation, the median and the interquartile range in the case of asymmetry and the maximum and minimum values observed were used. For the description of categorical variables, the number and percentage of patients per response category were used. The qualitative variables were compared using the chi-squared test and the quantitative variables using the t-Student test or variance analysis after study of variance homogeneity. A multivariate analysis using optimal scaling as regression procedure was also conducted.29

For the statistical analysis, the PASW Statistics package, version 18.0. A level of statistical significance of p<0.05 was be used for all statistical tests performed.

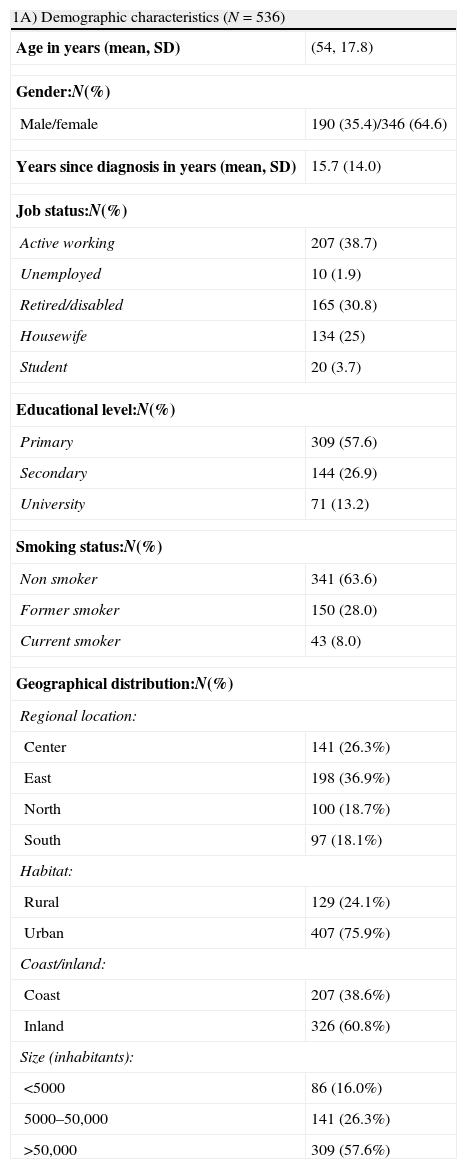

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical characteristicsA total of 536 patients were recruited in 40 Pulmonology Units throughout Spain. The majority were women (n=346, 64.6%) with a mean age of 54 years (SD=17.8 years) and 38.7% were active workers at the time of the study. Approximately 60% of the participants had primary studies and most of them lived in urban (76%) and inland (61%) areas with more than 50,000 inhabitants (57.6%). Only 8% of the participants were current smokers (Table 1).

Sociodemographic information.

| 1A) Demographic characteristics (N=536) | |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | (54, 17.8) |

| Gender:N(%) | |

| Male/female | 190 (35.4)/346 (64.6) |

| Years since diagnosis in years (mean, SD) | 15.7 (14.0) |

| Job status:N(%) | |

| Active working | 207 (38.7) |

| Unemployed | 10 (1.9) |

| Retired/disabled | 165 (30.8) |

| Housewife | 134 (25) |

| Student | 20 (3.7) |

| Educational level:N(%) | |

| Primary | 309 (57.6) |

| Secondary | 144 (26.9) |

| University | 71 (13.2) |

| Smoking status:N(%) | |

| Non smoker | 341 (63.6) |

| Former smoker | 150 (28.0) |

| Current smoker | 43 (8.0) |

| Geographical distribution:N(%) | |

| Regional location: | |

| Center | 141 (26.3%) |

| East | 198 (36.9%) |

| North | 100 (18.7%) |

| South | 97 (18.1%) |

| Habitat: | |

| Rural | 129 (24.1%) |

| Urban | 407 (75.9%) |

| Coast/inland: | |

| Coast | 207 (38.6%) |

| Inland | 326 (60.8%) |

| Size (inhabitants): | |

| <5000 | 86 (16.0%) |

| 5000–50,000 | 141 (26.3%) |

| >50,000 | 309 (57.6%) |

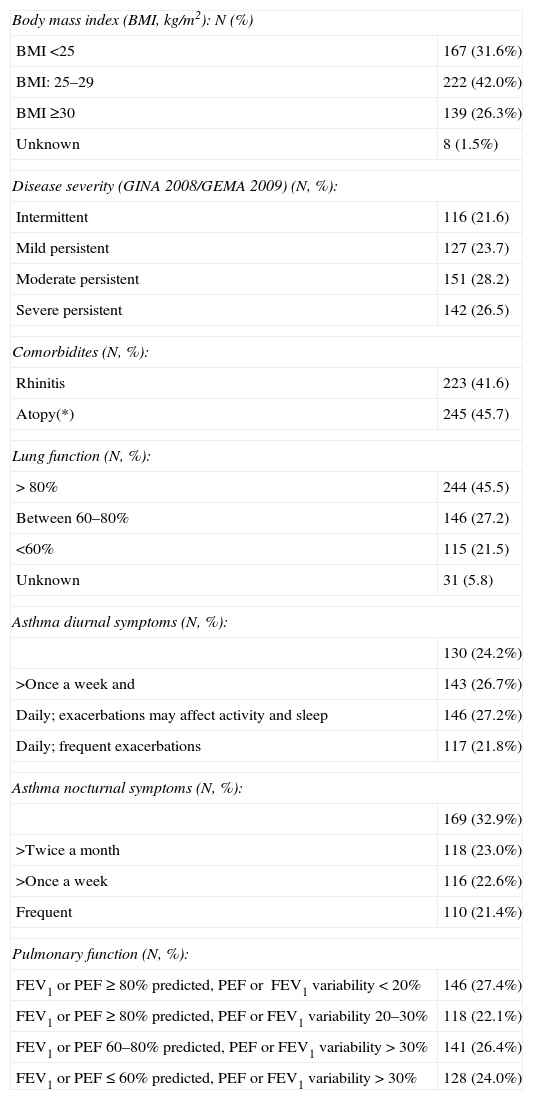

Approximately 68% of the patients were overweight (BMI≥25kg/m2) and 75% of the patients had mild to moderate disease (21.6% intermittent; 23.7% mild and 28.2% moderate disease). In addition, in 45.5% of the patients the lung function was >80%. With regards to asthma diurnal symptoms, 31% of the patients did not have daily symptoms (24.2% less than once a week and 26.7% more than once a week but less than once a day), while the remaining had daily exacerbations (in 27.2% the exacerbations could affect activity and sleep and in 21.8% the exacerbations were recurrent). Asthma nocturnal symptoms were frequent in 21.4% of the patients, while the rest experienced infrequent exacerbations [less than twice a month (32.9%), more than twice a month (23%) or more than once a week (22.6%)]. Considering comorbidities, more than 40% of the patients had rhinitis (41.6%) and some degree of atopy (45.7%) (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics.

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2): N (%) | |

| BMI <25 | 167 (31.6%) |

| BMI: 25–29 | 222 (42.0%) |

| BMI ≥30 | 139 (26.3%) |

| Unknown | 8 (1.5%) |

| Disease severity (GINA 2008/GEMA 2009) (N, %): | |

| Intermittent | 116 (21.6) |

| Mild persistent | 127 (23.7) |

| Moderate persistent | 151 (28.2) |

| Severe persistent | 142 (26.5) |

| Comorbidites (N, %): | |

| Rhinitis | 223 (41.6) |

| Atopy(*) | 245 (45.7) |

| Lung function (N, %): | |

| > 80% | 244 (45.5) |

| Between 60–80% | 146 (27.2) |

| <60% | 115 (21.5) |

| Unknown | 31 (5.8) |

| Asthma diurnal symptoms (N, %): | |

| 130 (24.2%) | |

| >Once a week and | 143 (26.7%) |

| Daily; exacerbations may affect activity and sleep | 146 (27.2%) |

| Daily; frequent exacerbations | 117 (21.8%) |

| Asthma nocturnal symptoms (N, %): | |

| 169 (32.9%) | |

| >Twice a month | 118 (23.0%) |

| >Once a week | 116 (22.6%) |

| Frequent | 110 (21.4%) |

| Pulmonary function (N, %): | |

| FEV1 or PEF≥80% predicted, PEF or FEV1 variability<20% | 146 (27.4%) |

| FEV1 or PEF≥80% predicted, PEF or FEV1 variability 20–30% | 118 (22.1%) |

| FEV1 or PEF 60–80% predicted, PEF or FEV1 variability>30% | 141 (26.4%) |

| FEV1 or PEF≤60% predicted, PEF or FEV1 variability>30% | 128 (24.0%) |

PEF, peak expiratory flow; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in the first second; (*) Definition: patient with rhinitis and/or conjunctivitis and/or eczema/atopic dermatitis.

Approximately 81% of the patients acknowledged to have received information regarding asthma control, being the most common source of information their assigned physician (general practitioner or pneumologist). Only 15% of the patients had participated in asthma control educational programs (ranging from 10% in intermittent asthma patients to 24% in severe asthma patients, p=0.005). Most of the educational seminars took place in hospitals (84%). Approximately 56% of the patients had a written plan for asthma self management (from 46% in intermittent asthma to 67% in severe asthma, p=0.006). General practitioners were the most common source for the asthma plan (82.0%) (Table 3).

Patient information about asthma.

| Information about asthma control (N, %): | |

| Yes | 433 (80.8) |

| No | 102 (19.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Sources of information (n=433): | |

| Media | 10 (2.3) |

| Friends and family | 3 (0.7) |

| General practitioner | 382 (88.2) |

| Non-longitudinal physician | 12 (2.8) |

| Internet | 1 (0.2) |

| Associations | 3 (0.7) |

| Others | 22 (5.1) |

| Participation in an asthma educational programme: | |

| Yes | 81 (15.1) |

| No | 454 (84.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Places (n=81): | |

| Hospital | 68 (84.0) |

| Tertiary care center | 7 (8.6) |

| Primary care center | 3 (3.7) |

| Associations | 2 (2.5) |

| Others | 1 (1.2) |

| Asthma self-management plan: | |

| Yes | 300 (56.0) |

| No | 235 (43.8) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) |

| Source (n=300): | |

| General practitioner | 246 (82.0) |

| Educational program | 20 (6.7) |

| Non-longitudinal physician | 4 (1.3) |

| Others | 27 (9.0) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.0) |

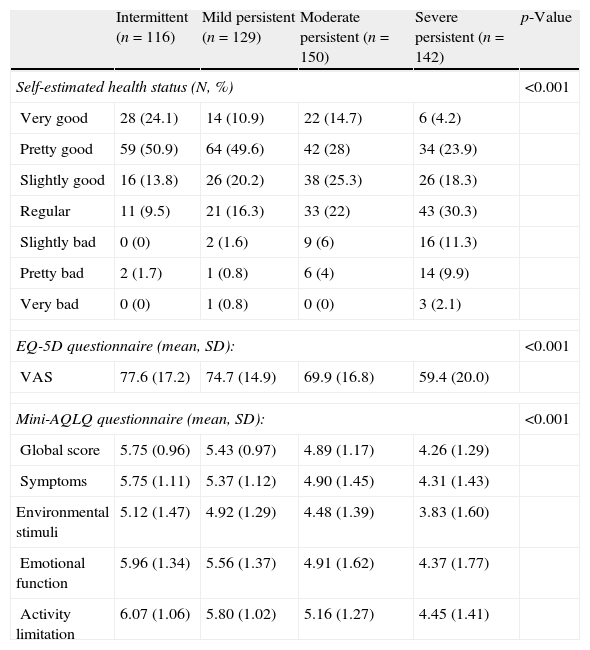

The results of the three QoL questionnaires are summarized in Table 4.

Self-estimated health status: The percentage of patients that declared to have a bad status (from slightly bad to very bad) ranged from 1.7% in those with intermittent disease to 23.3% in those with severe persistent disease (p<0.001).

EQ-5D: The mean VAS score ranged from 74.7 (mild persistent score) to 59.4 (severe persistent disease) (p<0.001). As shown in Fig. 1, that summarizes the influence of the disease on patients’ daily life, statistically significant differences were observed in all EQ-5D dimensions according to disease severity (p≤0.003).

Mini AQLQ: The mean global score ranged from 5.43 (mild persistent disease) to 4.26 (severe persistent disease), p<0.001.

Self-estimated health status and Mini-AQLQ questionnaire according to asthma severity.

| Intermittent (n=116) | Mild persistent (n=129) | Moderate persistent (n=150) | Severe persistent (n=142) | p-Value | |

| Self-estimated health status (N, %) | <0.001 | ||||

| Very good | 28 (24.1) | 14 (10.9) | 22 (14.7) | 6 (4.2) | |

| Pretty good | 59 (50.9) | 64 (49.6) | 42 (28) | 34 (23.9) | |

| Slightly good | 16 (13.8) | 26 (20.2) | 38 (25.3) | 26 (18.3) | |

| Regular | 11 (9.5) | 21 (16.3) | 33 (22) | 43 (30.3) | |

| Slightly bad | 0 (0) | 2 (1.6) | 9 (6) | 16 (11.3) | |

| Pretty bad | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | 6 (4) | 14 (9.9) | |

| Very bad | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | |

| EQ-5D questionnaire (mean, SD): | <0.001 | ||||

| VAS | 77.6 (17.2) | 74.7 (14.9) | 69.9 (16.8) | 59.4 (20.0) | |

| Mini-AQLQ questionnaire (mean, SD): | <0.001 | ||||

| Global score | 5.75 (0.96) | 5.43 (0.97) | 4.89 (1.17) | 4.26 (1.29) | |

| Symptoms | 5.75 (1.11) | 5.37 (1.12) | 4.90 (1.45) | 4.31 (1.43) | |

| Environmental stimuli | 5.12 (1.47) | 4.92 (1.29) | 4.48 (1.39) | 3.83 (1.60) | |

| Emotional function | 5.96 (1.34) | 5.56 (1.37) | 4.91 (1.62) | 4.37 (1.77) | |

| Activity limitation | 6.07 (1.06) | 5.80 (1.02) | 5.16 (1.27) | 4.45 (1.41) | |

Table 5 summarizes the variables with a significant effect on QoL of asthma patients (bivariate analysis). Those variables included geographical area and location, BMI, job status, educational level, information regarding asthma control, disease severity, including diurnal and nocturnal symptoms and finally pulmonary function. Patients with information about asthma presented a better QoL, quantified in the Mini-AQLQ total score, when compared with patients who had not received asthma education (p=0.012). Significant differences in ‘Symptoms’ (p=0.001) and ‘Activities’ (p=0.037) domains were also reported.

Variables influencing QoL (Mini-AQLQ questionnaire) of asthma patients.

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | p-Value |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | ||||

| Normal weight | 167 | 5.30 | 1.20 | 0.004 |

| Overweight | 222 | 5.00 | 1.22 | |

| Obese | 139 | 4.84 | 1.30 | |

| Job status | ||||

| Employee | 207 | 5.31 | 1.19 | <0.005 |

| Retired | 165 | 4.89 | 1.15 | |

| Unemployed | 10 | 4.39 | 1.64 | |

| Student | 20 | 5.41 | 1.00 | |

| Housewife | 134 | 4.81 | 1.36 | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary | 309 | 4.82 | 1.27 | <0.005 |

| Secondary | 144 | 5.26 | 1.11 | |

| Higher education | 71 | 5.50 | 1.17 | |

| Geographic situation | ||||

| Coast | 207 | 4.83 | 1.35 | 0.003 |

| Inland | 326 | 5.17 | 1.16 | |

| Area | ||||

| North | 141 | 5.56 | 1.02 | <0.005 |

| East | 198 | 4.91 | 1.27 | |

| Central | 100 | 5.04 | 1.16 | |

| South | 97 | 4.56 | 1.33 | |

| Information about Asthma control | ||||

| No | 102 | 4.76 | 1.20 | 0.012 |

| Yes | 433 | 5.11 | 1.25 | |

| Disease severity | ||||

| Intermittent | 116 | 5.75 | 0.96 | <0.005 |

| Mild persistent | 127 | 5.43 | 0.97 | |

| Moderate persistent | 151 | 4.89 | 1.17 | |

| Severe persistent | 142 | 4.26 | 1.29 | |

| Diurnal symptoms | ||||

| Intermittent | 130 | 5.74 | 0.95 | <0.005 |

| Mild persistent | 141 | 5.37 | 0.96 | |

| Moderate persistent | 147 | 4.80 | 1.18 | |

| Severe persistent | 117 | 4.16 | 1.34 | |

| Nocturnal symptom | ||||

| Intermittent | 169 | 5.55 | 1.04 | <0.005 |

| Mild persistent | 116 | 5.33 | 0.94 | |

| Moderate persistent | 117 | 4.85 | 1.19 | |

| Severe persistent | 110 | 4.12 | 1.34 | |

| Pulmonary function | ||||

| Intermittent | 146 | 5.60 | 1.04 | <0.005 |

| Mild persistent | 116 | 5.37 | 1.00 | |

| Moderate persistent | 142 | 4.89 | 1.18 | |

| Severe persistent | 128 | 4.28 | 1.30 | |

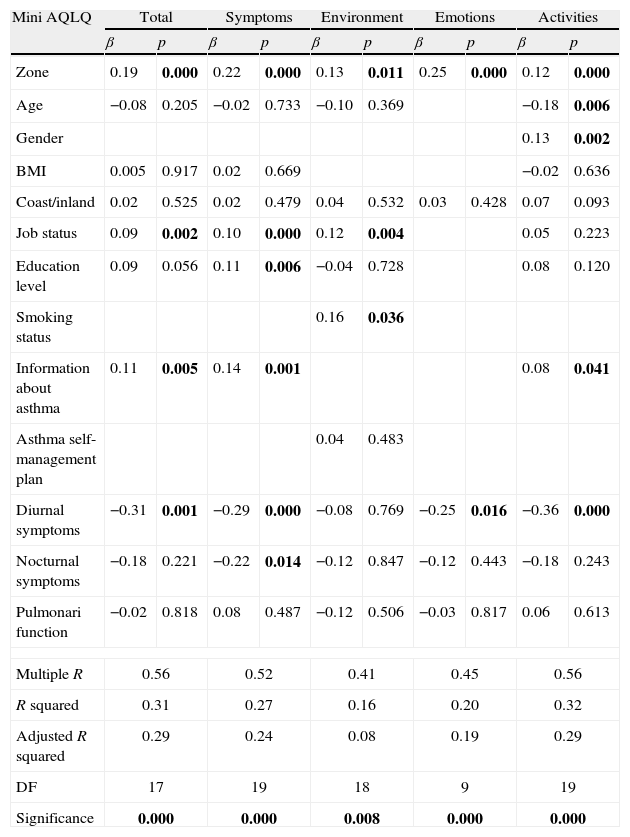

As per the final multivariate model (Table 6), with MiniAQLQ total score as dependent variable and after adjusting for all significant variables in the bivariate analysis, reported QoL was better for patients from Northern and Central Spain as compared with those from the South and the East (p<0.001), students and employed patients as compared with housewives and unemployed (p<0.01), for those who had received information about the disease compared with those who did not (p<0.01), for those with milder daytime symptoms (p<0.01) and for patients with higher education (p<0.05). Regional location was a statistically significant factor related with all the domains of the Mini AQLQ. In addition, job status, information about asthma and diurnal symptoms were related with at least two domains of the instrument.

Multivariate analysis. Regression coefficients on Mini-AQLQ scores.

| Mini AQLQ | Total | Symptoms | Environment | Emotions | Activities | |||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Zone | 0.19 | 0.000 | 0.22 | 0.000 | 0.13 | 0.011 | 0.25 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.08 | 0.205 | −0.02 | 0.733 | −0.10 | 0.369 | −0.18 | 0.006 | ||

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| BMI | 0.005 | 0.917 | 0.02 | 0.669 | −0.02 | 0.636 | ||||

| Coast/inland | 0.02 | 0.525 | 0.02 | 0.479 | 0.04 | 0.532 | 0.03 | 0.428 | 0.07 | 0.093 |

| Job status | 0.09 | 0.002 | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.223 | ||

| Education level | 0.09 | 0.056 | 0.11 | 0.006 | −0.04 | 0.728 | 0.08 | 0.120 | ||

| Smoking status | 0.16 | 0.036 | ||||||||

| Information about asthma | 0.11 | 0.005 | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.041 | ||||

| Asthma self-management plan | 0.04 | 0.483 | ||||||||

| Diurnal symptoms | −0.31 | 0.001 | −0.29 | 0.000 | −0.08 | 0.769 | −0.25 | 0.016 | −0.36 | 0.000 |

| Nocturnal symptoms | −0.18 | 0.221 | −0.22 | 0.014 | −0.12 | 0.847 | −0.12 | 0.443 | −0.18 | 0.243 |

| Pulmonari function | −0.02 | 0.818 | 0.08 | 0.487 | −0.12 | 0.506 | −0.03 | 0.817 | 0.06 | 0.613 |

| Multiple R | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.56 | |||||

| R squared | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.32 | |||||

| Adjusted R squared | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.29 | |||||

| DF | 17 | 19 | 18 | 9 | 19 | |||||

| Significance | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||

Measuring quality of life has become an increasingly important dimension in assessing patient well-being as well as drug efficacy. Such measurement has gained popularity as a clinical outcome, reaching beyond measurement of physical health or functional status.30 Quality of life studies are used to assess the impact experienced by patients in their daily lives due to their disease. In order to assess the global impact it is required to evaluate the disease impact on patients’ life in general as well as the deterioration that is more related to their disease. Thus, the use of both generic (EQ-5D and self estimated health status) and disease-specific questionnaires (mini AQLQ) allows the assessment of the specific effect of a particular disease and also to compare it with other pathologies.

Although it cannot be assumed that all questionnaires measure the same thing, the results of the present study have shown a clear correlation between the results obtained with the more asthma-specific questionnaire when compared with two more generic questionnaires. In addition, the Mini-AQLQ questionnaire was able to discriminate QoL between asthma severity levels. As severity of symptoms is theoretically related to QoL, it is an indicator of construct validity of the instrument.

With regards to the factors affecting quality of life of asthmatic patients it has been shown that the place of residence (North Central better than South), more active life (students and employed persons vs. house wives and unemployed), better asthma control (milder daytime symptoms) and knowledge about the disease (those who had received information vs. those who had not) improves the quality of life of asthma patients. According to our observations, a recent prospective study concludes that increased lifestyle physical activity was associated with improved in asthma quality of life.31 Likewise, obesity contributes to a deterioration in quality of life and a recent research shows that the Mediterranean diet can help improve the quality of life of asthmatics.32

It is clear that the only two factors that can be easily modified are the management of the disease as well as patient education. With regards to disease control, the goal of asthma treatment, as stated in GINA guidelines, and regardless of patient's asthma severity, should lead to achievement of complete disease control without, or with minimal, symptoms, both during day and night, without limitation of activities (including physical activities), with little or no need for rescue medication, lung function to near normal and no exacerbations.24,33

The second factor includes educational interventions. It has been demonstrated that educational and psychological counselling improves the quality of life and enhances patient's understanding of this chronic disease.8 However, such strategy has not been successful in other chronic pulmonary pathologies such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thus, the study by Gallefos et al., that examined the influence of an educational program on QoL after 12 months of follow up in patients with COPD and asthma showed an improvement in QoL and FEV1 only in asthmatic patients measured by the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire, as well as an associated increase in FEV1.22 Recently Saito et al.,34 show that asthma education may be useful to achieve stable control. Despite all this evidence, our article also highlights the few people who follow asthma education plans in Spain and should plan strategies in this respect is.

With regards to the limitations of the study, it is important to note the method used for patient selection. First, a probabilistic method was not used for patient inclusion, but rather the first patients who came to the consultation and met the inclusion criteria were selected. Second, due to the sampling technique used, stratified sampling, to be able to determine the variables with heavier effect on QoL, it is not possible to analyze the clinical characteristics of the general Spanish population of asthmatic patients.

In conclusion, only some factors that have a significant effect on patients’ QoL, such as symptom control and patient education on asthma control, are modifiable and therefore great effort should be tailored to improve such factors when managing asthma patients.35,36

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

The study, promoted by SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery), was supported by a restricted grant from MSD Spain. Editorial support was provided by Pipeline Biomedical Resources and supported by MSD, Spain.

José Luis Aller Álvarez (Hospital Clínico de Valladolid), Josep Armengol Sánchez (Hospital de Terrasa, Barcelona), Aurelio Arnedillo Muñoz (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz), Santiago Bargadí Forns (Hospital de Mataró, Barcelona), Teresa Bazús González (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón), Rosa Biescas López (Hospital General San Jorge, Huesca), Luis Borderías Clau (Hospital General San Jorge, Huesca), José Antonio Castillo Vizuete (CAP Jaume I, Vilanova i La Geltrú, Barcelona), Pilar Cebollero Rivas (Hospital Virgen del Camino, Pamplona), Carolina Victoria Cisneros Serrano (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid), Alfredo de Diego Damiá (Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia), M.a José Espinosa de los Monteros Garde (Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo), Estrella Fernández Fabrellas (Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia), Marta María García Clemente (Hospital Álvarez Buylla de Mieres, Oviedo), Silvia García García (Complejo Hospitalario de León), M.a Teresa González García (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), M.a Cruz González Villaescusa (Centro de Especialidades El Grao, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia), Manuel Haro Estarriol (Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta), José María Igancio García (Hospital Serranía de Ronda, Málaga), Antolín López Viña (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), Juan José Martín Villasclaras (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga), Miguel Ángel Martínez García (Hospital General de Requena, Valencia), Cristina Martínez González (Instituto Nacional de Silicosis, Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo), Eva Martínez Moragón (Hospital de Sagunto, Valencia), José Alberto Martos Velasco (Hospital San Rafael, Barcelona), Carlos Melero Moreno (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid), Alicia Padilla Galo (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga), Concha Pellicer Ciscar (Hospital Francesc de Borja, Gandia, Valencia), Antonio Pereira Vega (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva), Piedad Rivas (Complejo Hospitalario de León), Vicente Plaza Moral (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona), Gema Rodríguez Trigo (Hospital Juan Canalejo, A Coruña), M.a Ángeles Ruiz Cobos (Hospital Universitario La Princesa, Madrid), M.a Ángeles Sánchez Quiroga (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva), Joan Serra Batllés (Hospital General de Vic, Barcelona), Manuel Agustín Sojo González (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), Juan José Soler Cataluña (Hospital General de Requena, Valencia), Carlos Villasante Fernández-Montes (Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid).

The ASMACOST Study Group members are listed in Appendix A.