Studies demonstrate that both doctors and patients may use adrenaline auto-injector improperly and the usage skills are improved by training. In this study, we aimed to determine the appropriate frequency of training to maintain skills for adrenaline auto-injector use.

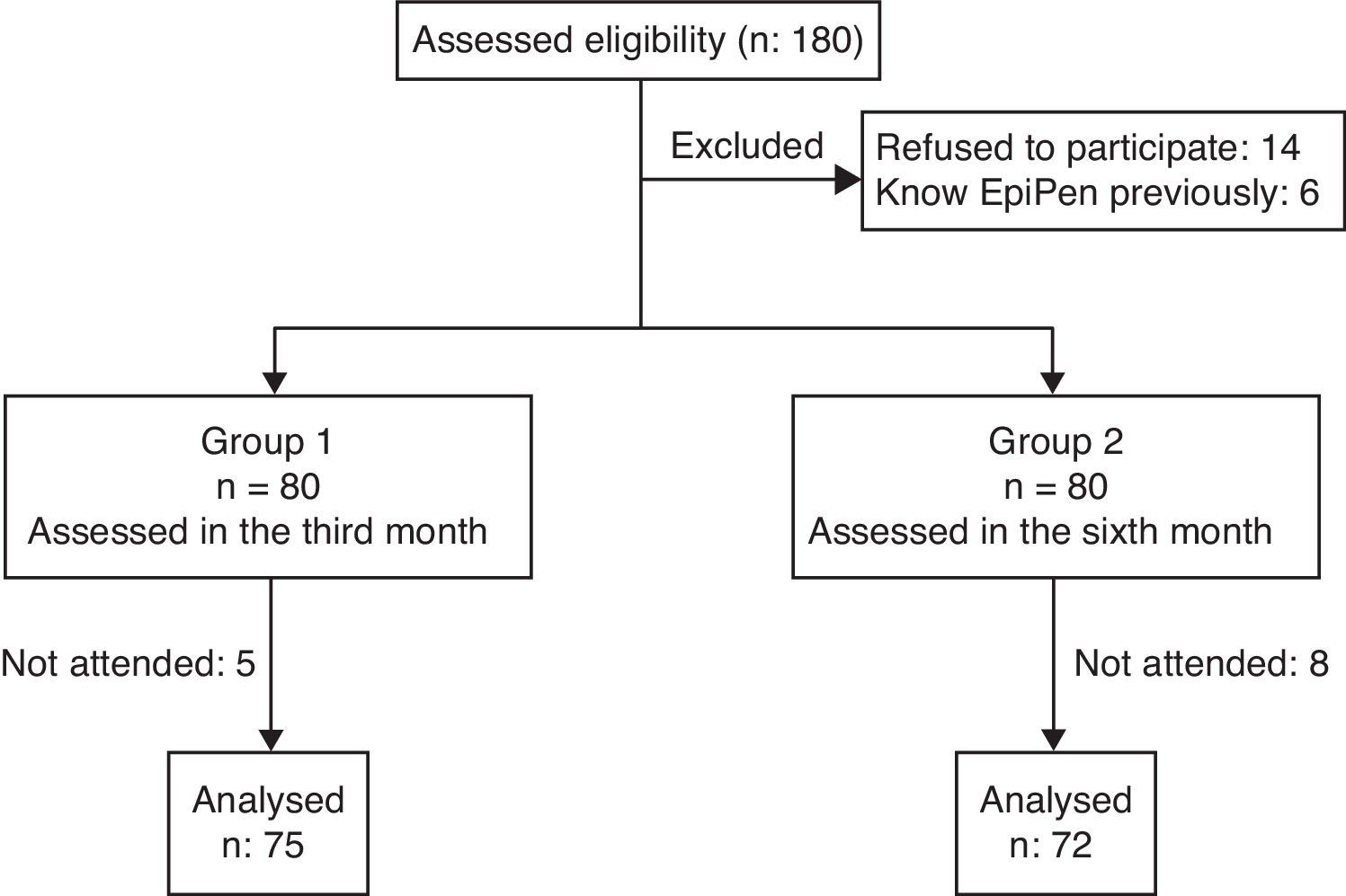

MethodsWe invited all interns of 2011–2012 training period. At baseline, all participants were given theoretical and practical training on adrenaline auto-injector use. The participants were randomly assigned into two groups. We asked those in group 1 to demonstrate the use of adrenaline auto-injector trainer in the third month and those in group 2 in the sixth month.

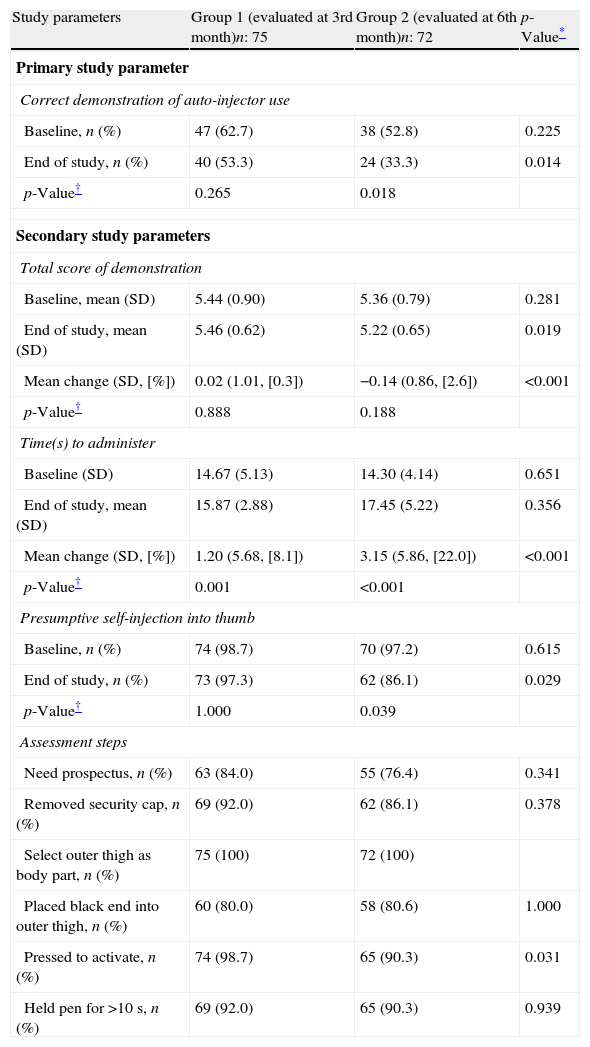

ResultsOne hundred and sixty interns were enrolled. Compared with the beginning score, demonstration of skills at all the steps and total scores did not change for the group tested in the third month (p=0.265 and p=0.888, respectively). However; for the group examined in the sixth month; the demonstration of skills for proper use of the auto-injector at all steps and the mean time to administer adrenaline decreased (p=0.018 and p<0.001, respectively). Besides, the group which was tested in the third month was better than the group which was tested in the sixth month in terms of demonstrating all steps (p=0.014), the total score (p=0.019), mean time of change to administer adrenaline (p<0.001) and presumptive self-injection into thumb (p=0.029).

ConclusionsAuto-injector usage skills of physician trainees decrease after the sixth month and are better in those who had skill reinforcement at 3 months, suggesting continued education and skill reinforcement may be useful.

Adrenaline is the first choice drug for the treatment of anaphylaxis.1 Therefore, all guidelines recommend a prescription of adrenaline auto-injectors for patients who have a risk of recurrence of anaphylaxis.1–3 Studies demonstrate that both doctors and patients may use the adrenaline auto-injector improperly4,5 and that usage skills are improved by training.6–8 Previously, Sicherer et al.7 evaluated the usage skills of the patients who were prescribed auto-injectors for food allergies, a year after the initial training. They reported that the usage skills of the patients for the auto-injector had decreased a year after. However, there is no study investigating the initial timing of decrease in this ability. This period of time is essential for the repeated training. We questioned when to perform a repeat training on adrenaline auto-injector usage: 3 or 6 months after the baseline training session? Therefore, we compared the usage skills of participants 3 or 6 months after the baseline training.

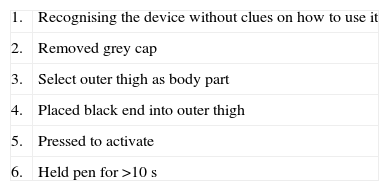

Materials and methodsWe informed all interns of 2011–2012 in our faculty about the study and enrolled the ones who gave informed consent. Exclusion criteria were; previous working experience in an allergy department, previous training on the use of adrenaline auto-injector and/or having an adrenaline auto-injector for self or for a family member currently or previously. We used trainers (EpiPen trainer®, Meridian Medical Technologies, Inc. Columbia, USA) which were exactly identical to the original adrenaline auto-injectors except for the medication and the needle. We provided a three-step written and visual instruction sheet on adrenaline auto-injector use. The instruction sheet was translated from the original trainer package insert. We used a system originally devised by Sicherer et al.4 to score the use of adrenaline auto-injector (Table 1). In this scoring system a maximum score of six points was possible (one point for each step). The instruction sheet covered all steps of the scoring system. Participants who succeeded in completing the six steps were accepted to have demonstrated the use of auto-injector correctly. In addition, playing with a wrong tip of auto injector trainer in order to eject the needle after removing safety cap was considered improper usage. At the beginning of the study, all the participants were trained one-to-one, both practically and theoretically. Baseline evaluation was done right after the first training. The training was repeated for those who failed in using it properly at this point. We randomly allocated participants into one of the two groups (group 1=use of adrenaline auto-injector trainer was tested 3 months after the first training; group 2=use of adrenaline auto-injector trainer was tested 6 months after the first training). No attempts were made to increase their stress during testing. Each participant was scored and timed separately by one of the authors (ET). The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Zekai Tahir Burak Maternity Teaching Hospital (number/date: 46/05.29.2012) and all participants gave their written informed consent.

Scoring system.4

| 1. | Recognising the device without clues on how to use it |

| 2. | Removed grey cap |

| 3. | Select outer thigh as body part |

| 4. | Placed black end into outer thigh |

| 5. | Pressed to activate |

| 6. | Held pen for >10s |

The primary study parameter was the rate of participants demonstrating proper adrenaline auto-injector use at the end of the study. Secondary study parameters were the mean total score, mean time to administer adrenaline auto-injector and presumptive unintentional injection injury rate which is defined as playing with the wrong tip of auto-injector trainer in order to eject needle after removing safety cap.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 11.5 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A descriptive analysis was used for the characterisation of patients. Qualitative variables were described in frequency and percentage while quantitative variables were expressed in medians. The normality of distributions was assessed with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Nominal data were evaluated by Pearson Chi-square or Fisher's exact test, whereas applicable and quantifiable data were compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Paired data were analysed using Wilcoxon signed-rank test or McNemar test for paired samples. The level of statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsWe screened 180 interns for eligibility and enrolled 166 for the study. Five interns who were trained on the use of adrenaline auto-injector previously and one who had adrenaline auto-injector for self-use were excluded. Study flow chart is given in Fig. 1. Seventy-five of the participants were female (51%) and the mean age was 24.1±2.11 years. The study groups were similar in both age and sex (p=0.692 and p=0.930, respectively). There was no difference between the groups for correct demonstration of the auto-injector use, mean time to administer, mean total scores of demonstration and in terms of playing with the wrong tip of auto injector trainer in order to eject needle after removing safety cap at the initial assessment (p>0.05 for all) (Table 2). There were no differences between the attended and non-attended physician trainees for correct demonstration of the auto-injector use, mean time to administer, and mean total scores of demonstration at the initial assessment (p>0.05 for all).

Comparison of study parameters between groups 1 and 2.

| Study parameters | Group 1 (evaluated at 3rd month)n: 75 | Group 2 (evaluated at 6th month)n: 72 | p-Value* |

| Primary study parameter | |||

| Correct demonstration of auto-injector use | |||

| Baseline, n (%) | 47 (62.7) | 38 (52.8) | 0.225 |

| End of study, n (%) | 40 (53.3) | 24 (33.3) | 0.014 |

| p-Value† | 0.265 | 0.018 | |

| Secondary study parameters | |||

| Total score of demonstration | |||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 5.44 (0.90) | 5.36 (0.79) | 0.281 |

| End of study, mean (SD) | 5.46 (0.62) | 5.22 (0.65) | 0.019 |

| Mean change (SD, [%]) | 0.02 (1.01, [0.3]) | −0.14 (0.86, [2.6]) | <0.001 |

| p-Value† | 0.888 | 0.188 | |

| Time(s) to administer | |||

| Baseline (SD) | 14.67 (5.13) | 14.30 (4.14) | 0.651 |

| End of study, mean (SD) | 15.87 (2.88) | 17.45 (5.22) | 0.356 |

| Mean change (SD, [%]) | 1.20 (5.68, [8.1]) | 3.15 (5.86, [22.0]) | <0.001 |

| p-Value† | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Presumptive self-injection into thumb | |||

| Baseline, n (%) | 74 (98.7) | 70 (97.2) | 0.615 |

| End of study, n (%) | 73 (97.3) | 62 (86.1) | 0.029 |

| p-Value† | 1.000 | 0.039 | |

| Assessment steps | |||

| Need prospectus, n (%) | 63 (84.0) | 55 (76.4) | 0.341 |

| Removed security cap, n (%) | 69 (92.0) | 62 (86.1) | 0.378 |

| Select outer thigh as body part, n (%) | 75 (100) | 72 (100) | |

| Placed black end into outer thigh, n (%) | 60 (80.0) | 58 (80.6) | 1.000 |

| Pressed to activate, n (%) | 74 (98.7) | 65 (90.3) | 0.031 |

| Held pen for >10s, n (%) | 69 (92.0) | 65 (90.3) | 0.939 |

Primary outcome parameter of the study was not different from baseline for the group tested 3 months after the training but time to administer adrenaline was prolonged (Table 2). In contrast, the group assessed after 6 months was worse compared to baseline for the primary outcome parameter, mean time to administer auto-injector and presumptive self-injection into thumb (Table 2). Holding auto-injector in place for 10s in the group assessed after 6 months was different compared to baseline (p=0.04) and all other assessment steps were similar in both groups compared to baseline (p>0.05 for all).

When the groups were compared in terms of study parameters, the group which was assessed after 6 months was worse than the group assessed after 3 months in all study parameters (Table 2).

DiscussionOur study demonstrated that the skills for the proper use of adrenaline auto-injector were stable within the first 3 months but decreased afterwards, at the sixth month. Earlier studies demonstrated that the adrenaline auto-injector usage skills increased by training for both physicians and patients.6–8 Kapoor et al.8 evaluated the proper usage skills of the patients who were prescribed an adrenaline auto-injector for food allergies within three critical steps (removal of the grey safety cap, selecting the appropriate site and pressing the EpiPen down until it “clicks”) and initiated the training. They determined that the patients’ skills of the adrenaline auto-injector use increased from 52.2% to 95.7% 3 months after the training. However, they did not evaluate the proper usage skills right after training. Even so, the percentage of patients able to demonstrate adrenaline auto-injector use after 3 months was satisfactory.

Sicherer et al.7 evaluated the auto-injector usage skills of the patients’ who had food allergy, at three successive stages: Before the training, right after the training and 1 year after the training. After a year, total score for the auto-injector usage skills had increased compared to pre-training but decreased compared to post-training. They reported that this decline was statistically significant for the two steps (recognising the device and holding it for 10s). Our study revealed a similar result that the failure made in holding the auto-injector for 10s step was just statistically significant in the group assessed after 6 months compared to baseline. In fact, 10s holding step was repeatedly reported as the most common failure step in other studies.5,7,9,10 However, recently Baker et al.11 demonstrated that 1s holding time is sufficient in an experimental study and stated that there is no scientific basis for the proposal for holding it for 10s as is stated in the prospectus of the auto-injector. In this case, less than 10s holding time may not be recognised as a failure.

Playing with wrong tip of auto injector trainer after removing safety cap was statistically greater for the group which was tested in the sixth month than the one which was tested in the third month. The failure in this step can be prevented by removing the safety cap after placing the black lead on the leg as proposed by Baker et al.11 or by using new adrenalin auto-injectors if available in the country.12

The evaluation in Sicherer's study is a year later than the initial training; it does not give an idea about the point when the decrease in the skills for auto-injector usage starts. Our results showed that the acquired skills decrease 6 months after the initial training. However, we performed the study with interns and not with patients, which may give indirect information about this issue. Also, although more realistic, data loss is common in follow up studies with patients as in the study by Sicherer et al.7 in which only 55% of the patients could be re-evaluated after a year. In contrast, our study was completed by 91.8% of participants.

In conclusion, auto-injector usage skills of physician trainees decrease after the sixth month and are better in those who had skill reinforcement at 3 months, suggesting that continued education and skill reinforcement may be useful. However, these results do not allow us to conclude that this is the time frame needed for patients/caregivers, too. Therefore, future studies are needed to determine the time frame on retraining of patients for adrenaline auto-injector usage skills.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestNo competing financial interests exist and there is no conflicts of interest statement for each author.