There is little information about the relationship between thymic hormones and atopy.

MethodsHuman thymostimulin was obtained from thymus of children who died in car crashes. These polypeptides were purified by a Sephadex G-50 column fractionation and incubated in vitro with human lymphocytes obtained from atopic and non-atopic subjects of different ages. The SDS-PAGE revealed at least the presence of three broad bands of proteins with 20, 30 and 60 kDa of molecular weight approximately.

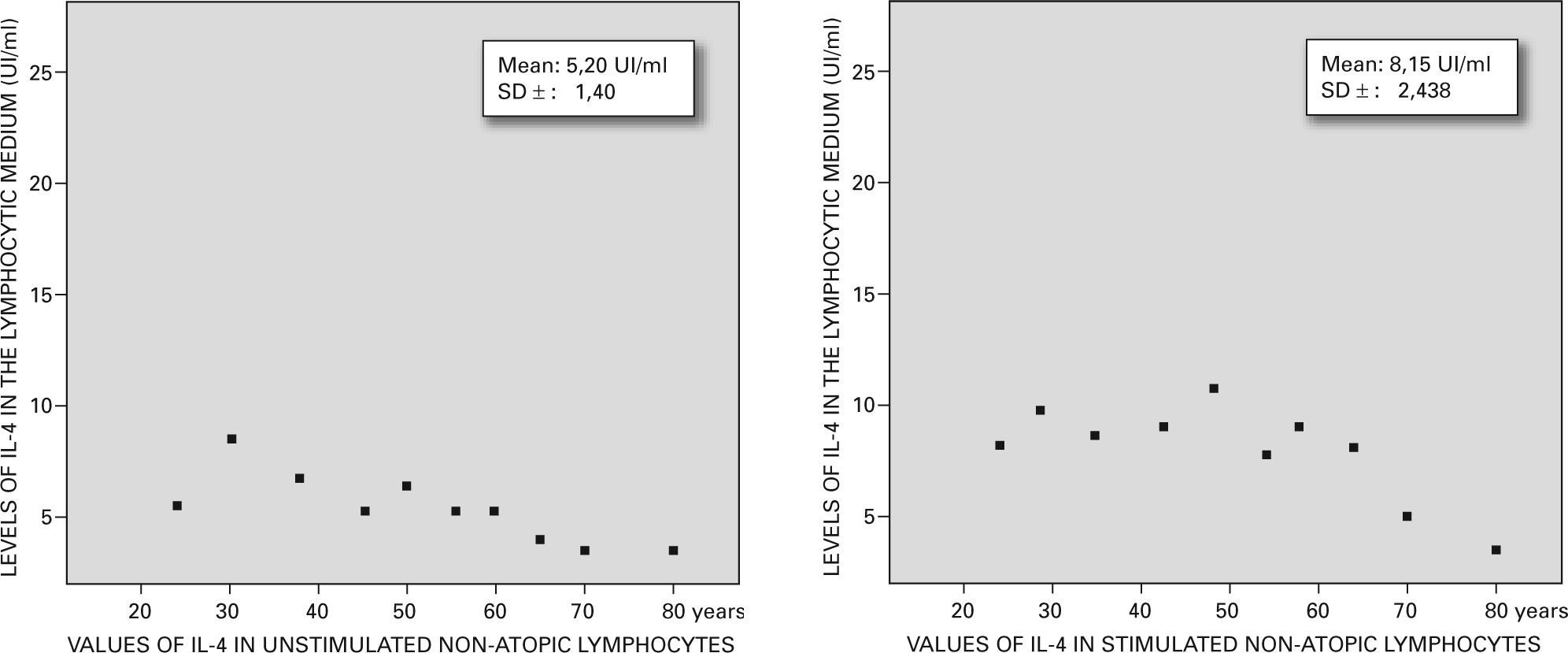

Levels of IL-4 from lymphocytic cultures were measured by ELISA and correlated with atopic and non-atopic status and with age. The non-atopic controls showed 5.20UI/ml±1.14UI/ml of IL-4 meanwhile the non-atopic cells stimulated showed 8.15 UI/ml±2.438UI/ml. On the other hand, the atopic cells revealed a spontaneous release of 12±1.812UI/ml meanwhile those stimulated by the thymostimulin showed 18.53UI/ml±1.40UI/ml.

ResultsThymic polypeptides were able to increase the levels of IL-4 in both groups although the atopic subjects showed the greater increase (p>0.001) independently of their age.

ConclusionsAs it has been suggested that these hormones could be used therapeutically in atopic subjects, our results warn about the adverse effects that could be produced with them.

Thymus and bone marrow are defined as the primary lymphoid organs. The former is a bilobulated lymphoepithelial organ that derives from the third and fourth pharyngeal sacs. In the thymus lymphocytes differentiate and mature and are exported into the blood stream as functional CD4+ and CD8+ lymphoid cells1–3.

The thymic epithelial cells produce several polypeptides baptised as thymic “hormones”. These peptides were characterised as thymulin (9 aminoacids with Zn); thymosine (or fraction 5 of bovine origin) that comprises subfractions such as α1, α2, β3 and β4; thymopoyetin (MW. 5560), thymostimulin (MW. 12000) and a thymic humoral factor (MW. 3200) all of them of bovine origin and another thymic serum factor of murine and pig source (MW. 860)4–6.

These peptides stimulate CD4+ and CD8+ lymphoid cells as was demonstrated by different in vitro techniques. In healthy humans and animals the serum levels of thymic hormones decrease with age, being undetectable in humans after the sixth decade7–9.

We obtained 3 peptides from human thymus that were put together and baptised as “thymostimulin” whose activity related to IL-4 levels was checked in vitro with human lymphocytes from atopic and non-atopic subjects in order to certify if the thymic hormones have some effect over human atopic conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODSSource of thymic hormonesThey were obtained from human thymus belonging to healthy children aged 5-10years old who passed away in car crashes. This experience was developed according to the Helsinki regulations for clinical investigations and with a proved protocol authorised by the Supreme Court of Justice. Histopathological studies were performed in order to check the viability of the organs using the conventional method with haematoxylin-eosin staining.

Tissue homogenisationThe preserved organs were weighted, cut into small pieces and submitted to a Virtis homogenizator. The mass thus obtained was mixed with saline solution pH 7.2 in a proportion of 3ml per gram. The homogenate was centrifuged at 14.000g and 2 fractions were achieved. The supernatant was treated with cetone and ammonium sulphate 50 % to remove lipids and serum proteins. The precipitate was discarded and dialysis against saline solution pH 7.2 was performed to obtain a final product to be submitted to column fractionation.

Sephadex column fractionationA Sephadex G-50 column was used. Equilibration of the 22mm × 780mm column and elution were done with 0.15M ClNa buffered with phosphate at pH 8 and 4°C. Three and a half millilitres of the supernatant were applied and aliquots of 1ml of the column eluate were collected at a speed of 20ml/min. The protein content of each eluate was determined by absorbance at 280nm OD in a Metrolab spectrophotometer and measured by the Bradford method10.

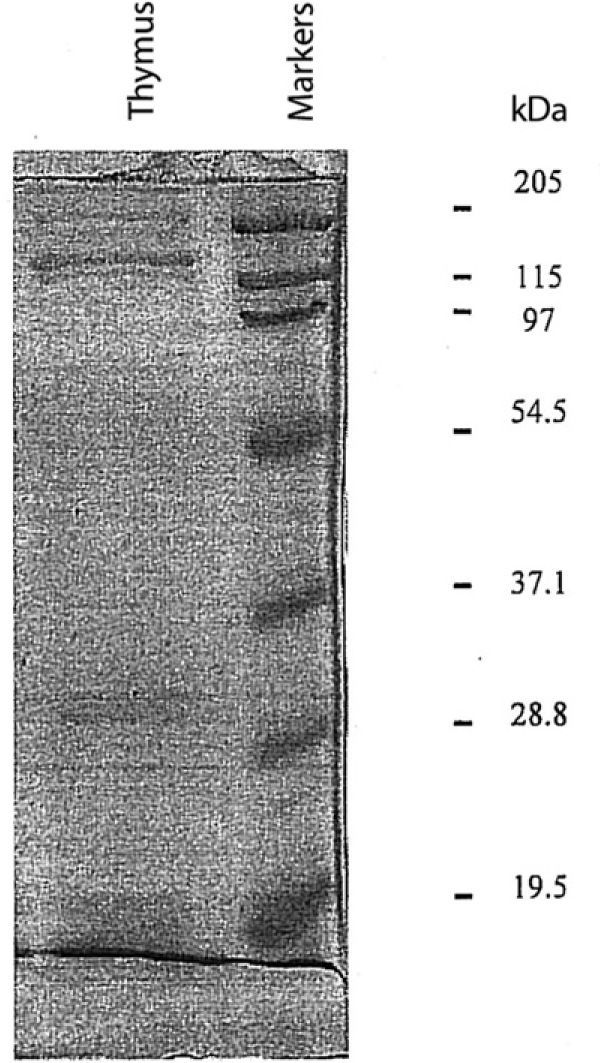

Molecular weights (MW)Marker proteins such as lisozyme (MW. 19.5kDa), trypsin inhibitor (MW. 28.8kDa), carbonic anhidrase (MW. 37.1kDa), ovoalbumin (MW. 54.5kDa), bovine serum albumin (MW. 97kDa), β-galactosidase (MW. 115kDa) and myosin (MW. 205kDa) (BioRad lot 161-0318), were applied to a Sephadex G-200 column of 780mm × 22mm that was equilibrated and eluated with a PBS-ClNa buffer 0.15M at pH 8 and 4°C. One millilitre of each substance was submitted to a Metrolab spectrophotometer at an OD 280nm. Protein content of the markers was 13.5mg in a volume of 1.5ml meanwhile the supernatant has 147 mcg in a volume of 3.5ml (42 mcg/ml).

Polyacrilamide gel electrophoresisOne-dimensional SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed following Laemmli's method using a 15 % polyacrylamide gel in a Mini-Protean II apparatus during 2 hours at 120V. Twenty microlitres of the hormone were put into the wells in different conditions of temperature and reduction to detect proteins with

Coomasie R-250 brilliant blue and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane11.

Lymphocyte donorsThirty healthy subjects suffering perennial allergic rhinitis, seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis and bronchial asthma with a family background of atopy and with serum IgE values of 180 ± 45 KU/L were selected according to the criteria defined by the American Thoracic Society. They showed positive skin tests to house-dust mite, cockroach and several pollen extracts. There were 20 women and 10 men aged 22 to 78years old. When blood samples were taken they had not used pharmacological medications during the previous 72 hours. As a control group, another 20 healthy subjects with similar ages (10 women and 10 men) without atopic background, negative skin tests to the same allergens and whose serum IgE levels were 18 ± 15 KU/L, were selected. They also contributed with 10ml of fresh blood obtained by vein puncture early in the morning. Human lymphocytes were separated following Boyum's technique using a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (d = 1.077g/cm3) and then stored in a culture medium such as RPMI 1640 (Gibco). The cells were adequately separated to evaluate the influence of thymostimulin and age12.

Measurement of IL-4 in the culture mediumOne millilitre of the lymphocytes whose viability was stained by the Giemsa technique was incubated with 10 mcg of thymostimulin during 24 hours at 37°C. Then the suspension was centrifuged and the quantity of IL-4 was measured by ELISA using a mice antihuman IL-4 antibody (Sigma Chemical Co. Clone n.° 34019.111) coupled with an enzymatic PAP-anti-PAP indicator system.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were run with SPSS for Windows. Fisher's exact test and independent t test were used for inter-group comparisons. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS- 1.

The twenty-one histopathologically normal thymus obtained weighed between 4.4 gr and 50.5 gr with a mean value of 26.86 gr, in parallel with the age of the dead children.

- 2.

The Sephadex G-50 column fractionation of the homogenate revealed 3 protein peaks in tubes 12-17; 33-37; and 39-43, with 42 mcg/ml of pure proteins detected by the Bradford technique. These peaks were put together and they constituted the “thymostimulin” hormone used in the experiments with atopic and non-atopic lymphocytes (fig. 1).

- 3.

The SDS-PAGE showed a broad range of 3 bands of apparent molecular weight of 15-20kDa in the first, 28-30kDa in the second and 50-60kDa in the last (fig. 2).

- 4.

The IL-4 levels of the lymphocytic culture showed that non-atopic controls unstimulated with the hormone, decrease with age (5.20 UI/ml ± 1.14 UI/ml) while, when stimulated with the hormone, showed 8.15 UI/ml ± 2.438 UI/ml.

On the other hand, the atopic lymphocytes revealed higher levels of IL-4 in both groups. The unstimulated lymphocytes produced 12 ± 1.812 UI/ml and the stimulated one synthesized 18.53 ± 1.40 UI/ml (p = 0.001) showing a remarkable peak between 35-55years old that we are unable to explain (figs. 3 and 4).

DISCUSSIONThe role of the thymus in the development and maturation of T-lymphocytes in humans especially during the embryonic and perinatal states is well known13–15. Thymectomy reinforces this statement considering that several primary immunodeficiencies occurred when the thymus is absent16–19. This organ decreases with age and in old people it appears as a little mass of lipofibrotic tissue. There are controversial results with the pharmaceutical use of thymic hormones of bovine origin in the treatment of different pathologies being immunological or not.

In atopics some authors proposed the use of thymic hormones in bronchial asthma although no biological parameters were checked to prove the mechanism of its hypothetical activity20,22–26.

We decided to evaluate the influence of a “thymostimulin” over the lymphocytes and their synthesis of IL-4. Thus we planned an in vitro experiment where the lymphocytes coming from atopic and non-atopic subjects were incubated with the thymic hormone measuring the production of IL-4 in the medium27–30.

The control group (non-atopic and unstimulated) showed a basal quantity of 5.20 ± 1.14 UI/ml and decreased in old age. When these lymphocytes were treated with our thymostimulin they showed an increase in the synthesis of IL-4 up to 8.15 ± 2.438 UI/ml even in older ages with a p = 0.01 between both experimental groups.

On the other hand the atopic lymphocytes revealed higher levels of IL-4 in both groups, the unstimulated 12 ± 1.812 UI/ml and the stimulated one 18.53 ± 1.40 UI/ml with a p = 0.001 and a curious peak between 35-55years old which is very difficult to explain.

When we compare both stimulated groups the significance was p > 0.001 meanwhile when the basal control group was compared with the atopic stimulated, the significance raised to p > 0.000001. These findings sustain the stimulating properties of the thymic hormones over human lymphocytes. Our data agree with those of Lurie who found no benefit in the treatment of asthmatic children with timulin21. According to our results the thymostimulin seem to enhance the TH2 profile, increasing the synthesis of IL-4 and the atopic status. Heterologous thymic hormones have been used in several clinical conditions with different results. We alert about the hazardous complications causing type I and/or type III side effects in atopic subjects as we proved in a patient with ophthalmic zoster who suffered cutaneous rashes, hives and angioedema with positive skin tests and RAST > 0.35 PRU/ml to a bovine thymic hormone31–33.

Nowadays a novel cytokine baptized as human thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) that promotes specific TH2 cell differentiation is increased in asthmatic airways and in atopic dermatitis. TSLP is a new target for a therapeutic approach.