Allergic diseases affect 15–20% of the paediatric population in the industrialised world. Most educational centres in Spain do not have health professionals among their staff, and the teachers are in charge of child care in school. The advisability of specific training of the teaching staff should be considered, with the introduction of concrete intervention plans in the event of life-threatening emergencies in schools.

Material and methodsEvaluation of the training needs constitutes the first step in planning an educational project. In this regard, the Health Education Group of the Spanish Society of Clinical Immunology, Allergology and Paediatric Asthma (Grupo de Educación Sanitaria de la Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica, Alergología y Asma Pediátrica [SEICAAP]) assessed the knowledge of teachers in five Spanish Autonomous Communities, using a self-administered questionnaire specifically developed for this study. The data obtained were analysed using the SPSS statistical package.

ResultsA total of 2479 teachers completed the questionnaire. Most of them claimed to know what asthma is, and almost one half considered that they would know how to act in the event of an asthma attack. This proportion was higher among physical education teachers. Most would not know how to act in the case of anaphylaxis or be able to administer the required medication. In general, the teachers expressed interest in receiving training and in having an interventional protocol applicable to situations of this kind.

DiscussionIt is important to know what the training requirements are in order to develop plans for intervention in the event of an emergency in school. Teachers admit a lack of knowledge on how to deal with these disorders, but express a wish to receive training.

Allergic diseases affect 15–20% of the paediatric population in the industrialised world.1 In fact, asthma is the most frequent chronic illness in childhood, with an estimated prevalence in the Spanish paediatric population of 7–10%.2 Thus, it can be deduced that there is an average of 1–2 pupils with asthma symptoms in each school class.3

Asthma in school can manifest spontaneously in a previously asymptomatic child or can worsen in a child with mild symptoms. A special case is asthma induced by exercise, since physical exertion can induce exacerbation of the disease. While not particularly frequent, there have been reports of fatal episodes in physical education classes and team sports activities in school.4,5

Food allergies are also common in schoolchildren, with an estimated overall prevalence of 4–7%.6 In this regard, it has been reported that 10–18% of all allergic reactions to foods occur in the school setting.7

Anaphylaxis is the most life-threatening expression of allergy. It has been estimated that 5–22% of all anaphylactic episodes in children occur in school,6,7 and some of these reactions can prove fatal – particularly in the context of food allergy.8,9

According to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), one out of every 300 Europeans suffers anaphylaxis at some point in life,10 and most European schools have at least one child at risk of developing anaphylaxis in the context of food allergy.11

Most educational centres in Spain do not have health professionals among their staff, and the teachers are in charge of child care and supervision in school.

Making school a safer place for children with serious health risks is a pending objective in European countries, and requires joint action on the part of parents, physicians and school staff.12 The situation varies greatly from one country to another, as well as between different school centres in one same country.13

The Paediatric Section of the EAACI has launched initiatives to define uniform intervention protocols in these circumstances, with general and specific objectives for the different allergic diseases.14 The Paediatric Section has drafted a document that aims to serve as a common guide to be adapted by each centre in accordance with its possibilities. The recommended activities include the presence in schools of people trained in recognising alarm symptoms and in providing emergency treatment with adrenalin and bronchodilators if needed. Furthermore, the safety of children with life-threatening allergic disease requires the supervising physician to provide a personalised action plan describing the allergy of the patient, the symptoms that may develop, and the emergency treatment required if such symptoms appear. The idea is not for the school's staff to diagnose and treat a reaction but to follow a clearly described series of concrete steps. Registries containing the required information are therefore recommended.

The existence of such plans in schools increases the safety of the children, although deaths have been reported15,16 despite emergency treatment. Prevention is therefore essential.

In Spain, pioneering programmes have been developed in the Autonomous Communities of Andalucía17 and Galicia,18 with coordination between the educational and emergency healthcare services. In March 2007, Galicia launched the School Alert (Alerta Escolar) programme with the main aim of ensuring immediate and efficient care of schoolchildren who suffer life-threatening emergencies due to anaphylaxis, epileptic seizures or diabetes-related hypoglycaemia.

The School Alert programme was likewise introduced in the Balearic Islands in 2014. This programme comes into effect when the parents enter a child with life-threatening chronic disease into the registry of the 061 emergency care service. In the event of an emergency situation, the school alerts 061, where a physician provides instructions on what to do until the medical staff arrive. The school teachers in turn receive prior training in the management of the life-threatening illnesses included in the programme.

Evaluation of the training needs constitutes the first step in planning an educational project. In this regard, the need for the teaching staff to have specific information and training, with concrete intervention plans, must be considered.

With the purpose of exploring this need for information, the Health Education Group of the Spanish Society of Clinical Immunology, Allergology and Paediatric Asthma (Grupo de Educación Sanitaria de la Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica, Alergología y Asma Pediátrica [SEICAAP]) evaluated knowledge about disorders such as asthma and anaphylaxis, and their management, among 2481 teachers in school centres in different Spanish Autonomous Communities.

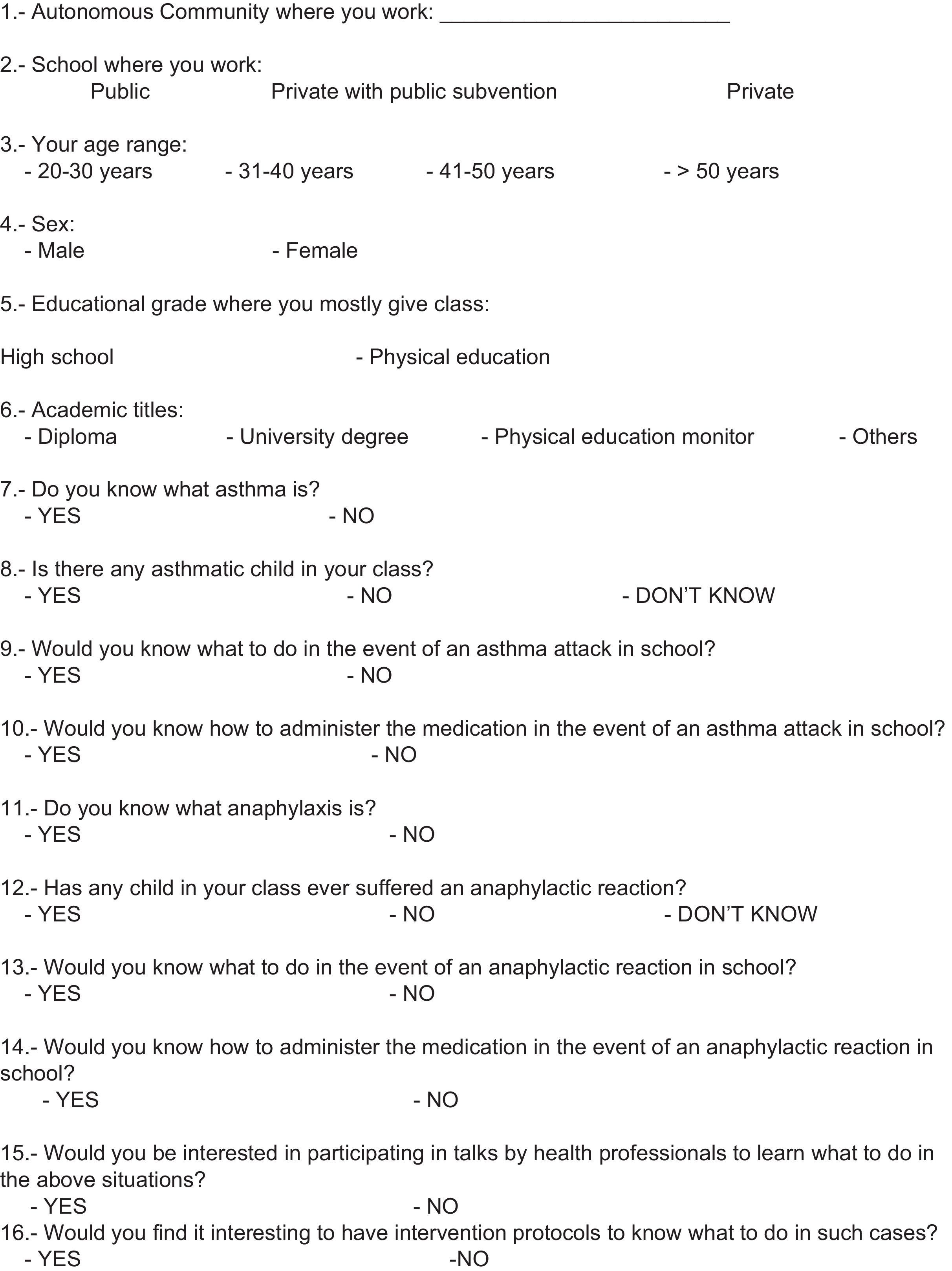

Material and methodsA self-administered questionnaire specifically developed for this study was distributed among nursery school, primary school, secondary school and high school teachers in five autonomous Communities (Andalucía, the Balearic Islands, Catalonia, Madrid and Valencia). The study covered the period between November 2013 and February 2014.

The directors of the schools were first contacted to explain the purpose of the study. Teacher participation was voluntary and anonymous. The questionnaires were completed in paper format or online, according to personal preference. Our aim was to obtain a sample representative of the provinces in which the study was made. However, given the voluntary nature of participation, bias may have been introduced due to the inclusion of those teachers most interested in the subject of the study. In any case, the results obtained appear to reflect the true situation found in the educational centres of these provinces, and possibly could be extrapolated to the rest of the country.

Due to the lack of a validated questionnaire, we developed a new questionnaire for this study, which was used in a pilot study to examine it for understanding and suitability. The questionnaire comprised 25 questions addressing the following items:

- •

Characteristics of the participating teachers and centres (workplace, age range, sex, academic training, type of centre according to financing mode, and educational grade).

- •

Knowledge and attitudes referred to asthma, anaphylaxis, epilepsy, diabetes and heart disease.

- •

Interest in receiving training in such diseases and in having intervention protocols in the event of emergencies that may occur in the school.

In this study we only analysed questions about knowledge and attitudes referred to asthma and anaphylaxis (Table 1).

The study variables were of a categorical nature, and the corresponding relative frequencies (%) were calculated in each case. The chi-squared test with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was used for the comparison of variables and the estimation of differences. The data were analysed using the SPSS version 20.0 statistical package.

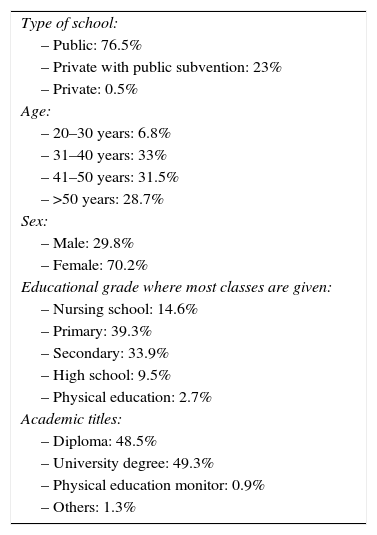

ResultsThe questionnaire was answered by 2481 teachers (29.5% males and 69.5% females) in the Autonomous Communities of Andalucía, the Balearic Islands, Catalonia, Madrid and Valencia. The majority (60.1%) were over 40 years of age. Seventy-six percent worked in public schools and 23% in private schools with public subvention.

Almost 73% of the participants were primary and secondary school teachers.

The distribution of participants by Autonomous Communities was as follows: Andalucía 44.8%, the Balearic Islands 30.5%, Valencia 13.7%, Catalonia 6.8% and Madrid 4.2%.

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the study sample.

Characteristics of the study sample.

| Type of school: |

| – Public: 76.5% |

| – Private with public subvention: 23% |

| – Private: 0.5% |

| Age: |

| – 20–30 years: 6.8% |

| – 31–40 years: 33% |

| – 41–50 years: 31.5% |

| – >50 years: 28.7% |

| Sex: |

| – Male: 29.8% |

| – Female: 70.2% |

| Educational grade where most classes are given: |

| – Nursing school: 14.6% |

| – Primary: 39.3% |

| – Secondary: 33.9% |

| – High school: 9.5% |

| – Physical education: 2.7% |

| Academic titles: |

| – Diploma: 48.5% |

| – University degree: 49.3% |

| – Physical education monitor: 0.9% |

| – Others: 1.3% |

The immense majority of the teachers (97%) claimed to know what asthma is – with no differences being observed in relation to the age of the teachers or of the schoolchildren. In reference to the different educational grades, over 30% of the teachers in secondary education and high school did not know whether they had asthmatic students in class, while 65.2% of the physical education teachers reported having some asthmatic student in class (p<0.001).

A total of 44.5% claimed to know what to do in the event of an asthma attack in class. This percentage increased to 75.8% in the case of physical education teachers (p<0.001). Knowing how to administer asthma medication in the event of an attack was found to depend on the age of the teacher, since the proportion of teachers who knew how to administer treatment in the youngest group (20–30 years) and oldest group (over 50 years) was 36%, versus 45.3% among the teachers between 31 and 40 years of age (p=0.004). Here again the physical education teachers yielded better results, since 56.1% claimed to know how to administer asthma medication, versus 29.7% of the high school teachers (p<0.001).

Knowledge and attitudes referred to anaphylaxisAs regards knowledge of anaphylaxis, the older teachers were seen to have more information on this clinical condition. In effect, 44.6% of those over 50 years of age knew what anaphylaxis is, versus 28.6% of those under 30 years of age (p=0.001). On the other hand, according to 3.5% of the teachers, some anaphylactic reaction had occurred in some student in their class.

The great majority (82.8%) would not know what to do in the event of an anaphylactic reaction in school, and a full 87.6% would not know how to administer the medication required in such cases. Knowing how to act in the event of anaphylaxis was again found to depend on the age of the teachers: almost 17% of those over 50 years of age claimed to know what to do, versus 7.7% of those under 20 years of age.

Demand for information and intervention protocolsA full 86.6% of the teachers expressed interest in attending courses on asthma and anaphylaxis, and in learning the skills and techniques needed in the event of an emergency. This percentage increased to 93.5% among the teachers between 20 and 30 years of age and dropped to 81.5% among those over 50 years of age (p<0.001). The high school teachers were those with the least interest in this respect (77.6%) (p<0.001).

Lastly, 96.8% of the teachers claimed to be interested in having an intervention protocol on how to act in the case of a child with an asthma attack or anaphylactic reaction in school.

DiscussionChildren spend about one-third of the day in school. Because of the high prevalence of allergic diseases and asthma, it is important to know the knowledge teachers have of these problems in order to allow them to intervene if necessary.

There have been many studies in this field over the last decade, evidencing the existing concern about the care of allergic children when in school.

The questionnaire used in our study evaluated teacher knowledge referred to management of the most common life-threatening chronic illnesses among their students. No objective assessment of knowledge was made; rather, our aim was to gain an impression that could serve to establish a starting point. On the other hand, the study sample does not intend to be fully representative of the population of teachers in the study setting, given the voluntary nature of participation. Furthermore, bias may have been introduced due to the inclusion of those teachers most motivated to answer the questionnaire.

The results obtained may give an idea of the true training needs, with a view to developing intervention plans to deal with episodes that may occur in school.

In the case of knowledge on asthma, a relevant finding is the fact that despite the high frequency of asthma in the paediatric population, 19.9% of the teachers were unable to identify asthmatic children in their class. A full 98% claimed to know what asthma is, but 54% admitted that they would not know what to do or how to administer the required medication. This does not seem consistent with the knowledge they claimed to have of the disease. This aspect is particularly relevant considering the importance of being able to help the children to correctly perform the inhalation technique during management of an asthma attack.

Regarding anaphylaxis, 82% of the reactions have been shown to occur in schoolchildren – in some cases in the actual educational centre.19 Anaphylaxis remains underdiagnosed and undertreated, even in the healthcare setting,20 and more so in schools.

The results of the questionnaire point to a great lack of information. In effect, 59.9% of the teachers did not know what anaphylaxis is, and 43.5% were unable to confirm whether any of their students had ever experienced such a reaction. It is unfortunate that despite the seriousness of anaphylactic reactions, the teachers were unable to identify those children at risk of suffering such problems. Possibly even more worrisome is the fact that up to 85% admitted that they would not know what to do in the event of an anaphylactic reaction, and only 11% claimed to know how to use adrenalin.

Teachers appear to recognise their lack of knowledge on how to deal with these diseases, but are also interested in receiving training and in having protocols explaining how to act in emergency situations.

Most studies on the management of allergic disorders in school are recent. The first Spanish study exploring knowledge about asthma among teaching staff was carried out by Cobos in 2001, and involved 933 teachers from 27 schools in seven cities. Twenty-five percent of the teachers reported having asthmatic children in their class, and 91% admitted having little knowledge on how to deal with possible asthmatic attacks.21

Similar findings have been published in other countries. A study of information on asthma among teachers in Turkey found the level of knowledge to be insufficient, and underscored the need for educational programmes.22

Korta-Murua et al. investigated the impact of an educational intervention referred to knowledge about asthma among school teachers in the Basque Country. The authors concluded that the intervention significantly improved knowledge of asthma among the teachers, although after three months this knowledge was partially lost–hence pointing to the need for sustained educational intervention.23

In a studied conducted on the island of Tenerife,24 84% of the teachers reported having at least one asthmatic child in class, though 64% admitted that they would not know what to do in the event of an asthma attack. Fifty-eight percent considered themselves capable of helping with administration of the inhaled medication, although 95% considered that they needed further training.

Watson et al. underscored the importance of standardised training protocols to improve teacher knowledge and self-confidence in dealing with emergencies in children with allergic diseases in school.25

In the United States, Shah et al. found that teacher training, compared with a group of controls, improved knowledge of food allergy as assessed by means of a questionnaire before and after training. The number of positive responses increased significantly in the group that received training.26

In another study conducted among public school teachers in the city of New York, the participants admitted having limited knowledge of food allergy and did not consider themselves to be prepared to deal with an anaphylactic reaction. The authors concluded that counselling strategies and learning modules are needed to educate the teachers.27

The validation of the Spanish version of the New Castle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ) in 537 teachers has recently been published. While the results obtained were not available at the time of the present study, they will make it possible to establish comparisons.28

Based on the above, it can be affirmed that the problem is of a global nature, and that the results obtained using different methods show the situation in schools to be far from safe for children with asthma or food allergies. Furthermore, the deficiencies seen in our country are also found elsewhere. The care of allergic children in school is a social problem that implicates the school staff, health professionals and families, as well as the pertinent government authorities.

The fact that the problem is of a global nature is evidenced by the publication of studies in different geographical settings, with results consistent with those of our own study, and the drawing of common conclusions: there are shortcomings in terms of the identification of these children, and in the training of school staff. Furthermore, sustained training efforts are required, with the adoption of protocols for the prevention of risks and intervention in the event of signs of disease.

School teachers require knowledge of the signs and symptoms of allergic diseases and must be able to deal with clinical manifestations that may be mild but can also prove life-threatening.

FundingThe authors declare that this study has received no funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that there are no patient data in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that there are no patient data in this article.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments have been made involving either humans or animals in this study.

Coordinator of the Health Education Group of the SEICAP.

Members of the Health Education Group of the Spanish Society of Clinical Immunology, Allergology and Pediatric Asthma (Grupo de Educación Sanitaria de la Sociedad Española de Inmunología Clínica, Alergología y Asma Pediátrica [SEICAAP]).