Cow's milk and egg are the most frequent causes of food allergy in the first years of life. Treatments such as oral immunotherapy (OIT) have been investigated as an alternative to avoidance diets. No clinical practice guides on the management of OIT with milk and egg are currently available.

ObjectivesTo develop a clinical guide on OIT based on the available scientific evidence and the opinions of experts.

MethodsA review was made of studies published in the period between 1984 and June 2016, Doctoral Theses published in Spain, and summaries of communications at congresses (SEAIC, SEICAP, EAACI, AAAAI), with evaluation of the opinion consensus established by a group of experts pertaining to the scientific societies SEICAP and SEAIC.

ResultsRecommendations have been established regarding the indications, requirements and practical aspects of the different phases of OIT, as well as special protocols for patients at high risk of suffering adverse reactions.

ConclusionsA clinical practice guide is presented for the management of OIT with milk and egg, based on the opinion consensus of Spanish experts.

Cow milk (CM) and egg are the most frequent causes of food allergy in the first years of life.1 Two recent European studies conducted by the EuroPrevall group have reported an incidence of CM allergy and egg in the first two years of life of 0.54% (0.57% among the infants recruited in Spain) and 0.84% (0.78% among the infants recruited in Spain), respectively.2,3 A study carried out in the Valencian Community (Spain), in which the diagnosis was confirmed by oral food challenge, reported an incidence of CM allergy of 0.36% in the first year of life.4

The only currently approved treatments for food allergy are avoidance and administration of emergency medications on accidental exposure.5

New treatment options have therefore been explored – the most widely studied being oral immunotherapy (OIT). Milk-OIT and egg-OIT induces changes in the immune system and favors the development of desensitization in most patients, though there is little evidence on its long-term safety and efficacy.6

Although the immunological mechanisms intervening in OIT have not been fully clarified, this type of therapy is known to induce a decrease in the activation and release of mediators from mast cells and basophils, with an increase in specific IgG4 titers, a decrease in specific IgE levels, the activation of specific regulatory T cells, and Th2-mediated response inhibition.7–10Adverse reactions (AR) are frequent and can also manifest in the maintenance phase. Although such reactions are generally mild, they may prove more serious, with the need for ephinefrine administration. While sometimes associated to cofactors (e.g., exercise, infections), AR may appear unpredictably with doses that were previously well tolerated.5,11

Desensitization is achieved in most patients, though in at least 20% of the cases OTI fails due to the appearance of AR. For this reason, new therapeutic strategies must be developed, such as for example adjuvant therapy with anti-IgE antibodies, in order to broaden the scope of application of OIT.12

The long-term outcome and time needed to achieve permanent tolerance of the causal food are not known.5,13,14 On the other hand, it must be taken into account that prolongation of the maintenance phase can lead to treatment adherence problems.15

These elements of uncertainty are the reason why OIT is currently still advised only in the research setting, not in clinical practice.

However, the fact is that CM and Egg-OIT has already been introduced in clinical practice and forms part of the management options of many hospitals in Spain. Different treatment protocols are being used; it is therefore necessary to define the bases for regulating the requirements, with standardization and optimization of the treatments, and particularly reduction of the risks in clinical practice.

The aim of this document is to offer a clinical guideline in the use of OIT in patients with IgE-mediated allergy to CM and egg-white proteins. By incorporating the data derived from the extensive available experience, the guide will attempt to establish the guidelines for OIT during the build-up phase and subsequent maintenance treatment, with the maximum safety guarantees.

The ultimate outcome is to improve clinical practice and to allow the professionals involved in such treatment to feel that their work is endorsed by the scientific societies SEICAP and SEAIC.

MethodologyDevelopment of the guide has been based on the following elements:

- 1.

A literature search and review referred to:

- o

Studies and meta-analyses of milk and egg-OIT published between 1984 and June 2016, found in the PubMed database.

- o

Doctoral theses on milk and egg-OIT and egg published in Spain.

- o

Abstracts referred to milk and egg-OIT presented between 2010 and 2014 on occasion of the congresses of the SEICAP, SEAIC, EAACI and AAAAI.

- 2.

Opinion consensus among Spanish researchers with experience in OIT.

- 3.

Levels of evidence and grades of recommendation of the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).16

CM and egg allergy in children is generally associated to a good prognosis. Approximately 85% of all infants with CM allergy develop tolerance by three years of age.17–20 Egg-allergy persists for a longer period of time, though approximately 65% of all affected patients reach tolerance by 6 years of age.21,22

However, more recent studies suggest a tendency toward longer persistence of milk allergy(36% of the patients do not tolerate milk at 12 years of age)23 and egg-allergy (32% of the patients do not tolerate egg at 16 years of age).24

Patients with milk or egg allergy have a real and non-negligible risk for suffering a further reaction, which may prove seriousFood allergy is the most frequent cause of anaphylaxis, particularly in children and young adults.25 Recent meta-analyses26,27 describe an anaphylactic reaction rate of 4.93 cases per 100 children allergic to foods.

In the period between 1998 and 2011, an increase in admissions due to anaphylaxis was recorded in Spanish hospitals, particularly involving children, and caused by foods – most often CM and egg.28

Deaths are rare, however, and the mortality rate has remained stable in recent years, with an estimated 1.8 deaths per million patients with food allergy per year.

Although deaths secondary to anaphylaxis caused by milk and egg are infrequent, the risk must not be underestimated, particularly in patients with asthma and adolescents. These cases occur mainly among children and young adults, and can be avoided through correct preventive or therapeutic interventions.

A prospective multicenter study carried out in the United States29 involving a cohort of 514 patients allergic to milk or egg under 15 months of age were followed-up on for three years. Sixty-two percent of the children suffered some reaction, and over one-half experienced more than one reaction per year. The annual rate for all foods being 0.81 reactions per year. Milk caused twice as many reactions as egg (42.3% versus 22%; respectively). Most reactions were result of accidental exposure to allergen (87.4%), and 11.4% were severe. No significant differences in this percentage being observed between milk and egg.

In a cross-sectional observational study conducted in Spain involving children between 18 months and 12 years of age with milk allergy, AR secondary to accidental exposure were recorded in 40% of the patients in the previous year, and 15% of those reactions were severe.30

The psychosocial impact of food allergyFood allergy affects different aspects of the life of the patients and their environment, with a negative impact upon the quality of life of both the affected individuals and their families, due to the repercussions of the disorder in their school and family life, and to its economical impact.

Apart from the importance of the physical manifestations of food allergy, the need to follow an exclusion diet intrinsically produces emotional, psychological and social problems. Furthermore, those patients that have suffered a severe reaction live in fear of a possibly fatal reaction.31–35All these reasons lead patients to demand a solution to their problems extending beyond avoidance diets, and encourage allergologists and pediatricians to search for new therapies such as OIT.

Current state of OIT: efficacy and safetyHas milk and egg-OIT been shown to be effective?Two successive outcomes in time must be considered in OIT: desensitization and the acquisition of sustained unresponsiveness.

OIT is defined as the administration of progressively increasing doses of the food causing the allergic reaction, with the aim of reducing the symptoms resulting from natural exposure, i.e., OIT intends to secure desensitization and, if possible, permanent tolerance of the food.

Oral desensitization is characterized as the reversible reduction of clinical reactivity or responsiveness achieved after exposure to progressively increasing doses of a food. Oral desensitization may be lost within a few days or weeks after suspending the regular intake of the food.

Sustained unresponsiveness is defined as the permanent absence of clinical reactivity to a food even if it is not consumed on a regular basis.

Desensitization efficacyDesensitization efficacy is defined by the increase in the reaction threshold measured as the food dose tolerated by the patient.

This guide considers two degrees of desensitization efficacy:

- •

Complete desensitization: when the patient is able to tolerate a dose equivalent to a full-serving dose of the food, thus allowing it to be added to the diet without restrictions. In the case of CM and egg, complete desensitization is achieved when 200ml of CM or one raw or cooked egg-white, respectively, are tolerated by the patient (depending on the established treatment outcome).

- •

Partial desensitization: when the patient is able to increase the threshold of tolerance of the food as compared to the tolerated dose before OIT, but does not tolerate a full-serving dose of the food, or some of the commonly consumed presentations of the causal food. The maintenance of partial desensitization would be justified in order to avoid AR caused by the inadvertent intake of small amounts of the food, and to facilitate continuation of the desensitization process after a period of time.

Desensitization may prove more effective in small children, which suggests that immune modulation would be easier to achieve if started at an early age, as has been postulated in the case of subcutaneous immunotherapy with aeroallergens. Only partial desensitization is achieved in most patients with severe clinical manifestations of anaphylaxis and high specific IgE titers.36,37

Meta-analyses of controlled studies conclude that OIT is effective in inducing desensitization in most patients with IgE-mediated CM and egg allergy, though the results in terms of long-term tolerance are not clear38–40 (Level of evidence I. Grade of recommendation A).

Efficacy in acquiring sustained unresponsivenessThe ultimate aim of OIT is to achieve sustained unresponsiveness of the food, without AR and without having to consume it on a regular basis.

The published studies reveal an evolution toward tolerance in between 38 and 75% of all patients with CM and egg allergy subjected to OIT, after a maintenance period of 1–4 years.41,42 Recent meta-analyses demonstrated a substantial benefit of ITO in terms of desensitization (risk ratio (RR)=0.16, 95% CI 0.10, 0.26) and suggested, but did not confirm sustained unresponsiveness (RR=0.29, 95% CI 0.08, 1.13).43

The factors that influence the acquisition of tolerance are not known, but may involve the time elapsed from complete desensitization, the doses administered during the maintenance phase, the degree of sensitization to the causal food, and other factors inherent to the patient, such as adherence to therapy. It is also not clear whether sustained unresponsiveness can be achieved in all allergic patients provided OIT is maintained long enough, or whether some patients will never be able to achieve permanent tolerance.

Thus, OIT has been shown to be effective in achieving desensitization in patients with CM and egg allergy (Level of evidence I. Grade of recommendation A),but the maintenance period needed to secure sustained unresponsiveness is not known, and it is not clear whether all patients can eventually reach tolerance.

Is OIT safe?The safety of OIT is one of the most important factors to be considered when applying the evidence gained from studies to the clinical practice setting.

The evidence on the safety of OIT has been examined by systematic reviews and meta-analyses over the last three years, and the conclusion is that AR are frequent during OIT – being observed in up to 91.5% of all treated patients35 and in 16% of the administered doses.44

Most of the described AR were mild and self-limiting: itching of the mouth and lips, perioral urticaria, generalized urticaria or erythema, abdominal symptoms, rhinoconjunctivitis, mild laryngeal spasms and mild bronchospasm.40,45 There have also been reports of severe anaphylactic reactions,46,47 and the published controlled clinical trials have found that between 6.7 and 30.8% of all patients subjected to milk-OIT and 20% of those subjected to egg-OIT required ephinefrine administration.36,37

Eosinophilic esophagitis have been reported in with OIT,48 though in no case was esophageal disease discarded before OIT was started. A recent systematic review concluded that the combined prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis diagnosed after OIT (milk, egg, peanut or wheat) was 2.7.49

AR may cause patient withdrawals in 3–20% in the case of milk-OIT and in 0–36% in the case of egg-OIT.50

In conclusion, OIT is not without risks. Most of the AR are mild, though more serious reactions are also possible.

Indications and contraindicationsWhat patients may currently be considered as candidates for milk and egg-OIT?- •

Patients with IgE-mediated CM and egg allergy.

- •

Patients that maintain clinical reactivity to CM at two years of age, as confirmed by oral food challenge51 (Level of evidence II. (Grade of recommendation B)(*).

- •

Patients that maintain clinical reactivity to egg at 5 years of age, as confirmed by oral food challenge52 (Level of evidence II. Grade of recommendation B)(*).

Optionally, OIT can also be considered in patients that tolerate cooked egg but

develop symptoms in response to small amounts of raw or undercooked egg.

Moreover, the treatment must be accepted by the patient and/or family after being informed of the risks and benefits of OIT, and the need for prolonged maintenance therapy (see Supplementary Materials: Appendix 1 patient/family/tutor information and informed consent models (Spanish version)).

*The absence of a lower age limit may be considered in the more severe cases, when specific IgE has not been found to decrease at the successive controls, or in patients with anaphylactic reactions due to of the lesser likeliness of spontaneous tolerance and the greater risk of severe reactions.23,24

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

In any case, the personal and family circumstances and preferences must be taken into account, along with the available resources for administering OIT with full guarantees.

What patients may currently NOT be considered as candidates for milk and egg-OIT?Patients with:

- •

Not IgE mediated CM and egg allergy.

- •

Uncontrolled asthma. In such cases control of the disease must be achieved before OIT is started.

- •

Severe atopic dermatitis. In such cases control of the disease must be achieved before OIT is started.

- •

A previous diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis.

- •

Inflammatory bowel disease.

- •

Mastocytosis.

- •

Immunosuppressive treatment (chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies – with the exception of omalizumab –, etc.).

- •

Disorders and/or treatments contraindicating ephinefrine use.

- •

Difficulty in understanding the risks and benefits of the procedure and family and social factors that complicate the long-term maintenance therapy. This includes parental conflicts that may adversely affect treatment.

- •

Unability of the parents to follow the instructions, identify reactions or administer medication (ephinefrine)

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Milk and egg-OIT: build-up phaseThe build-up phase is the time between the first dose of the food and the moment at which the target dose is achieved

Depending on the protocol used, this period may last from a few days to several months.

Requirements referred to healthcare personnel, equipment and facilities: quality and safety standards- •

Medical personnel with experience or trained in Allergology or Pediatric Allergology Departments/Units/Clinics, and familiarized with the procedures of OIT.

- •

Allergy or Pediatric Allergy Departments/Units/Clinics with Day Hospital facilities in which the patient can be monitored after administration of the food doses scheduled during the build-up phase of OIT.

- •

Interventional protocols for the medical and nursing personnel, appropriate space and therapeutic resources (drugs and material for cardiopulmonary resuscitation) for treating the AR derived from therapy, including severe anaphylaxis.53

- •

Prolonged monitoring Units (up to 24h) available in the medical center in the event of severe anaphylaxis (in the setting of the Pediatric Department in the case of children).

- •

Safety plan for the patient or relatives, including:

- a.

Instructions on administration of CM or egg doses.

- b.

A written interventional protocol in the event of allergic reactions at home during OIT.

- c.

Rescue medication to treat allergic reactions: ephinefrine auto-injectors, antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, salbutamol.

- d.

Registry forms for documenting AR and incidents during treatment.

- e.

Availability of telematics or telephone communication allowing easy and rapid contact with the supervising physician.

The intervention plan must be revised periodically – including the ephinefrine self-injection technique.

The pediatrician or general practitioner should be informed in writing that the patient is undergoing OIT and that allergic reactions may occur during such treatment. An explanation of the intervention plan in the event such reactions occur should also be provided.

Studies to be carried out before starting the build-up phase in milk and egg OITThe following information must be available in order to assess the AR risk factors, define the required treatment protocol, and study the evolution toward tolerance:

- 1.

Clinical data:

- •

Level of severity of CM or egg allergy

- •

Prior tolerance of milk or egg from other ruminants and veal

- •

Other food allergies

- •

Digestive symptoms of lactose intolerance, not IgE mediated allergy, or gastroesophageal reflux

- •

Bronchial asthma

- •

Atopic dermatitis

- 2.

Immunoallergic data:

- •

Skin prick tests with CM (milk, alpha-lactoalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, casein) or egg (egg-white, ovoalbumin, ovomucoid) protein extracts, and extracts from goat and/or sheep milk.

- •

Serum total and specific IgE titers against CM proteins (milk, alpha-lactoalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, casein) or egg (egg-white, ovoalbumin, ovomucoid) proteins, and goat and/or sheep milk proteins.

- •

Controlled oral challenge testing with CM or cooked egg or egg white to establish the clinical responsiveness threshold. This test is not required in case of a severe reaction after milk or egg exposure in the previous year.

- •

In patients with bronchial asthma or atopic dermatitis, clinical stabilization of the patient and adequate control of the disease with the required treatment is required.

- •

Suspected lactose intolerance needs to be confirmed.

- •

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux or recurrent digestive symptoms must be referred to the gastroenterologist for evaluation and the exclusion of possible eosinophilic digestive diseases.

Packaged commercial milk is the preferred presentation because it is the way that is routinely consumed at home and requires no preparation. It is sold pasteurized, sterilized or subjected to upperization/UHT (Ultra High Temperature). No allergenic differences have been demonstrated among them.

The most frequently consumed presentation corresponds to milk subjected to upperization/UHT (5–8s at a temperature between 150 and 200°C, followed by rapid cooling). Depending on the brand and percentage fat content, the amount of proteins ranges between 2.9 and 3.3g/100ml. In order to perform OIT, an easily obtainable commercial product/or brand should be used, with a protein content of about 3g/100ml. Using different brands of milk in the course of treatment implies possible variability in the protein doses administered. The differences among milk brands are minimal when small doses are administered; however, the patient/family must be informed of the possible variations when larger milk volumes are administered.

Commercial powdered milk for adultsIt is characterized by the removal of 95% of the water by atomization and evaporation processes. The protein content in this case is 34.9g/100g and reconstitution in 200ml yields 7g of proteins. This higher protein content must be taken into account when adjusting the dose during OIT. The greater advantage is that the product is long lasting and easy to transport and storage.

Should milk with or without lactose be used?Whole milk with lactose can be used, though the age of the patient must be taken into account as the incidence of lactose intolerance increases with age, reaching a prevalence of 20%–40% in the Spanish adult population

Processed (baked) milkUp to 75%54 of all children with CM allergy tolerate foods prepared with milk baked at high temperatures (180°C). In patients that do not tolerate extensively heated milk, desensitization has been attempted with this form of the product-with little success. Most of the patients (79%) were unable to complete the treatment because of AR, and only a limited increase in the tolerance threshold was observed in those who did complete the treatment.55

Fermented dairy productsOnly one study describes the use of yogurt from the 100ml dose of milk in the build-up phase.56 Fermented liquid or creamy diary products are commonly administered in the clinical setting in Spain usually in the last part of the build-up phase. With lesser doses, fermented dairy products are difficult to handle. The greater advantage of these product is the better acceptance among patients that reject the flavor of milk and milkshakes.

Mixture of CM and goat or sheep milkMilk-OIT is specific and does not result in tolerance of milk from other mammalian species. Up to 26% of the patients that tolerate CM after OIT continue to experience reactions when coming into contact or consuming sheep/goat milk or cheese,57 due to caprine caseins lacking cross-reactivity with CM caseins.58 Consequently, once OIT has been completed, patient sensitization and tolerance evaluation to sheep or goat milk is required before it can be introduced in the diet.

In order to prevent these AR, combined immunotherapy with CM and goat and/or sheep milk in the build-up phase has been proposed. However, no data warranting their simultaneous introduction in the build-up phases are currently available. Only one study of simultaneous milk-OITand goat milk has been published to date.59

At present, after finishing the build-up phase of OIT with CM does not exist any parameter capable of predicting tolerance to other types of milk, except in patients with negative IgE against milk from other species or with prior tolerance to theses milks

In conclusion, the product offering most advantages is liquid CM, with or without lactose, in its commercial container.

Once the dose of 100ml has been achieved, liquid milk may be replaced by fermented dairy products.

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Egg-OITEgg allergenicity is substantially modified by heating and other processes such as baking with cereal flour.60,61 In this regard, baked egg is less allergenic than cooked egg, and the latter in turn is less allergenic than raw egg.62,63 Therefore, the way in which the allergen source is prepared could influence the outcomes of Egg-OIT.

The egg allergens in class 1 allergy are found in egg-white, therefore, this is the allergen source to be used, with or without yolk.

Dehydration, pasteurization and freeze-drying guarantee microbiological safety and facilitate egg dosing and preservation. In vitro and in vivo studies having demonstrated allergenic equivalence to natural raw egg.63,64

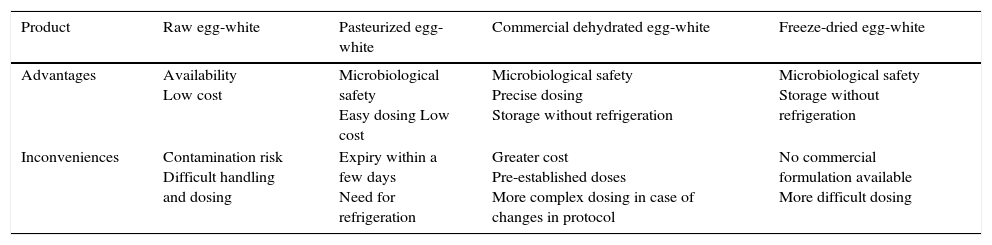

From the practical perspective, the advantages and inconveniences of the main raw egg-white products are summarized in Table 1.

Advantages and inconveniences of the different raw egg-white products in OIT.

| Product | Raw egg-white | Pasteurized egg-white | Commercial dehydrated egg-white | Freeze-dried egg-white |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Availability Low cost | Microbiological safety Easy dosing Low cost | Microbiological safety Precise dosing Storage without refrigeration | Microbiological safety Storage without refrigeration |

| Inconveniences | Contamination risk Difficult handling and dosing | Expiry within a few days Need for refrigeration | Greater cost Pre-established doses More complex dosing in case of changes in protocol | No commercial formulation available More difficult dosing |

Few studies have used cooked egg. The results obtained65–69 are similar to those recorded with raw egg-white, though it must be taken into account that these protocols result in tolerance to cooked egg, and tolerance to raw egg-white should be assessed.66

A recent study70 has demonstrated that hydrolyzed egg is not clinically effective for achieving desensitization to cooked egg.

In conclusion, raw egg white products and cooked egg may be effective in achieving desensitization, though further studies with cooked egg are needed in order to compare its efficacy versus the raw food.

If the objective to achieve tolerance only to cooked egg, desensitization with heated egg with or without small amounts of raw egg will suffice.

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

What dose should be reached?Milk-OITThe aim of milk-OIT is to allow the allergic patient to follow a diet free of restrictions with regard to this food in its different presentations. However, the goal of the build-up phase must be to achieve tolerance to the previously target dose.

In the different published protocols of milk-OIT, the most frequently proposed dose is 200ml. This amount can be consumed in a single dose, or in several fractions during the day. However, some protocols establish a target dose of up to 250ml. These amounts represent between 6 and 7.5g of milk and are considered to be the normal liquid milk intake among non-allergic individuals in our setting Tolerance to this dose is considered complete desensitization, while lower doses would represent partial desensitization.

With regard to the consumption of cheese made from CM, the protein concentration of the different varieties must be taken into account (see Supplementary Materials: Table II).

In patients sensitized to milk proteins from other species (goat/sheep/buffalo, etc.), tolerance must be evaluated through controlled challenge tests before introduction in the diet, except in the case of tolerance to these milks prior to CM-OIT.

In patients with risk factors (section F.1), a final milk dose of 15ml may be considered, as it could offer protection against minor accidental exposures and favors the raising of the tolerance threshold over time.71

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Egg-OITThe choice of OIT outcome or target should be based on the preferences of the patient, parents or tutors, after having provided sufficient information on the chances for successful desensitization to a normal food portion. This outcome in turn can be modified according to the evolution of the desensitization process, seeking a less ambitious target with lower egg doses. In this regard, the priority concern is to protect the patient against possible AR upon the accidental exposure to the food.

We thus may establish three OIT outcomes, associated to different maximum doses:

- •

Protection against traces or cross-contamination in patients that do not tolerate baked egg with flour.

- •

A diet containing cooked egg, with restriction of raw egg.

- •

A normal diet without restrictions.

Only one study has considered this treatment outcome,72 suggesting that a 300mg dose of powdered egg-white or its equivalent would suffice to maintain protection against accidental ingestion due to traces, cross-contamination, or labeling error, and even against the amount of egg contained in an average-size pastry.

A normal diet without restrictionsMost OIT protocols with egg are programmed to achieve desensitization to a normal food portion, i.e., one whole egg73–77 that is, representing tolerance to about 30ml of egg-white, 45–50ml of egg, 10g of pasteurized whole egg77 or 3.6g of egg-white proteins,78–80 reflecting the protein content of the egg-white in a medium to large egg.

Although some studies52,72 suggest that desensitization to low or medium doses guarantees desensitization to high doses over the middle to long-term in an important percentage of patients, the usual practice is to seek tolerance to a whole egg or egg-white, in order to normalize the diet within weeks or a few months.

Conclusions- •

The maximum dose to be reached at the end of the build-up phase depends on the intended outcome of therapy, which in turn is conditioned to the severity and personal preferences of the patient, after providing him or her with the necessary information.

- •

Tolerance to a whole egg or egg-white is necessary in order to be able to follow a normal diet.

- •

If the aim is tolerance only to cooked egg, the patient must be warned of the need to avoid raw or undercooked egg.

- •

If the aim is to protect against accidental exposure, a 2.2ml dose of raw egg-white or its equivalent may be established, though further studies are needed in this regard.

Few studies have compared the efficacy and safety of the different proposed milk dose increments. A Spanish study in children with strong sensitization and manifestations of anaphylaxis showed that a protocol comprising dose increments of no more than 20% increased the safety of the treatment.81

It is advisable to administer the dose with a full stomach and avoiding intense physical exercise in the subsequent 2–3h

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Egg-OITThe largest dose increments are associated with an increase in AR.37,73,82

Regarding the rate of the dose increments, rush protocols as well as intermediate or slow protocols have been described, different time intervals. Dose escalation is usually carried out weekly,52,56,77,79,83 though some authors introduce dose increments every 1–3 days64,65,74 or every two weeks.37,52,72,78 There have been reports of cluster or rush protocols66,67 with a duration of 12 and 5 days

In conclusion, the currently available data suggest that protocols involving proportionally lower dose increments may be safer both when administered at greater intervals (every 1–2 weeks) and when carried out on a daily basis. The dose escalation rate therefore does not seem to affect the safety of the procedure.

(Level of evidence II. Grade of recommendation B).

Are rush/cluster protocols in milk-OIT and egg-OIT safe? In which patients can they be used?Almost all protocols use a cluster protocol in the first 1–2 days. Successive doses are administered every 30–60min with increments that vary between 50 and 100%, depending on the protocol used. In general, the administered doses during these first days are lower than the response threshold of the patient.

Few studies have been published on OIT rush protocols with CM, which are completed in a period of 3–7 days. A total of 32 children with CM allergy have been treated, with good results (complete desensitization in 59% and partial desensitization in 31% of the cases); allergic reactions similar to those observed with the standard protocols being reported.56,84–86

The published rush protocols with egg are also scarce66,67 and have been carried out combining pasteurized or dehydrated egg-white with cooked egg. The reported efficacy rates have been 86.9% and 100%, respectively, though reaching a maximum dose of one whole cooked egg. The results obtained with these protocols are similar to those reported with more prolonged protocols69,79,80,87,88 with efficacy rates of between 82% and 93%, reaching maximum protein amounts equivalent to one whole egg-white.

No studies have compared the safety profile of rush protocols with egg versus that of the slow protocols. The studies involving rush protocols66,67 describe mild and moderate AR in 78% and 100% of the patients, respectively, though the reported dropout rates were not greater than in the case of the slow protocols. Later studies61,66 have suggested the use of rush protocols in less severely affected patients, and only in individuals with low sensitization: sIgE to egg-white <22kU/l and to ovomucoid <12kU/l.

The advantage of rush protocols is that they allow the specialist to have direct control of the entire build-up phase (without home-administered doses), up to the maximum maintenance dose, with increased control over the cofactors (physical exercise, infections, gastroenteritis, etc.) during this phase of the treatment process.

ConclusionsThe published rush protocols have been found to be effective and less time-consuming. Their safety profile is similar to that of the published slower protocols.

Rush protocols may be useful in less severely affected patients without the described risk factors for adverse reactions.

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

What should the starting dose be? Are fixed starting doses for the build-up phase preferred, or should the doses be individualized?Although protocols involving fixed doses are the most frequently used option, individualized doses can also be administered, starting the build-up phase according to the results obtained in the baseline oral challenge test.

Few studies have described the use of protocols with individualized starting doses. In these protocols the doses range between 10 and 50% of the threshold dose89 or start with the last tolerated dose in the oral challenge test.80,90

Individualized protocols may be indicated in patients that have reacted to medium or high doses of the food in the challenge tests with the advantage of shortening the build-up phase, with a lesser consumption of healthcare resources and greater patient convenience, although the build-up starting dose in relation to the threshold dose has not been established (While this concept is not well defined, a cumulative dose of half an boiled egg or 50ml of milk or more may be considered a medium to high tolerance threshold).

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Are there any distinguishing features of the AR that manifest during milk-OIT and egg-OIT? Is there any most frequent type of reaction?Abdominal pain is a frequent symptom and cause of patient withdrawal in egg-OIT.52,77,91 It may be more common than the skin symptoms,40 and in some cases are associated to diarrhea and/or vomiting.

In some cases the gastrointestinal reactions may be of such intensity and duration that they prove refractory to treatment (corticosteroids, antihistamines, etc.). Some authors consider abdominal pain a particular reaction and no longer classify them as mild when they last more than 15min, require the patient to lie down, or cause skin paleness or tachycardia.92 In these cases, treatment with ephinefrine has been assessed. Although there are no studies in this regard, a number of authors advocate the use of this drug in such cases, in view of the favorable experience gained, with rapid resolution of these problems which often limit the progression of OIT.

No particular or distinguishing AR have been reported during milk-OIT.

Are antihistamines, disodium cromoglycate, montelukast and/or ketotifen effective in preventing AR during the build-up phase of OIT with food?It is not clear whether the prophylactic administration of antihistamines or other drugs is useful in preventing AR during the build-up phase of OIT with food. Although conducted in patients with allergy to peanut, a simple-blind, placebo-controlled study compared a group premedicated with ketotifen versus placebo,93 and recorded a decrease in the number of gastrointestinal AR in the ketotifen group. Likewise, a retrospective study with only 5 patients94 evaluated the use of montelukast during OIT, and found the drug to be useful in preventing abdominal pain.

In conclusion, currently there is not enough evidence to allow the generalized recommendation of these drugs for the prevention of AR during the build-up phase of OIT with food, though they could be used when adverse effects complicate continuation of the treatment.

General recommendations in the build-up phaseAdminister the dose with food.

Avoid physical exercise in the 2–3h after dosing and non steroidal antiinflammatory drugs in the 2–3h around food ingestion.

In the event of an intercurrent disease:

- •

Asthma attack: 50% reduction of the dose.

- •

Gastroenteritis: 50% reduction of the dose or suspension during the acute phase of the disease for a maximum of three days, followed by resumption under in-hospital control with 50% reduction of the dose.

- •

Febrile upper airway infection: return to the previous tolerated dose.

(Level of evidence V. Grade of recommendation D: expert opinion).

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Copublished in the Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology.