Psychiatric disorders are seen frequently in atopic diseases. The present study aims to evaluate the frequency of psychiatric disorders and the severity of psychiatric symptoms in pre-school children with cow's milk allergy.

MethodsThe parents of the pre-school children with cow's milk allergy were interviewed in person and asked to fill out the Early Childhood Inventory-4 form.

ResultsThe cow's milk allergy group included 40 children (27 male, 13 female) with mean age, 44.5±14.7 months, and the control group included 41 children (25 male, 16 female) with mean age, 47.6±15.2 months. It was established that 65% of the group with cow's milk allergy received at least one psychiatric diagnosis, while 36.6% of the control group received at least one psychiatric diagnosis, with a statistically significant difference (p=0.02). Within the psychiatric disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (odds ratio: 4.9, 95% CI: 1.472–16.856, p=0.006), oppositional defiant disorder (odds ratio: 5.6, 95% CI: 1.139–28.128, p=0.026), and attachment disorder (odds ratio: 4.8, 95% CI: 1.747–13.506, p=0.004) were found significantly higher compared with the healthy control group. When the groups were compared in terms of psychiatric symptom severity scores, calculated by using the Early Childhood Inventory-4 form, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders severity (p=0.006) and oppositional defiant disorder severity (p=0.037) were found to be higher in the cow's milk allergy group.

ConclusionPsychiatric disorders are frequent and severe in pre-school children with cow's milk allergy.

Population-based studies report that the prevalence of cow's milk allergy (CMA) ranges from 1.9 to 4.9% in young children.1 UK data from 2008 indicated that 2.3% of children aged 1–3 years suffer from CMA, the majority of these presenting with non-IgE-mediated CMA.2 In general, the prognosis for CMA is good, with up to 80–90% of children developing tolerance before 3 years of age.3 However, CMA can persist up to school age and may be associated with the later development of other allergic diseases such as asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic dermatitis,4 as well as other disease manifestations such as recurrent abdominal pain and psychiatric disorders.5,6 Hak et al.6 reported that Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is more common in children with cow's milk intolerance. Also, ADHD is common not only in children with CMA, but also in children who have atopic eczema, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.7 Studies have shown that other psychiatric diseases, e.g., Attachment Disorder (AD), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and Tourette syndrome (TS), are also frequently seen in atopic diseases.8,9 Although studies to date have reported that psychiatric disorders are seen frequently in atopic diseases, no studies have extensively assessed the psychiatric illness symptoms in pre-school children with CMA. The purpose of this study is to ascertain the frequency and severity of psychiatric disorders in pre-school children with CMA by using the Early Childhood Inventory-4 (ECI-4) form.

Materials and methodsThis multi-centre study was conducted between February 2014 and March 2015 and involved children with CMA who were admitted to the Pediatric Allergy and Asthma Clinics of Inonu University, Ondokuz Mayıs University, Adnan Menderes University, and Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Training and Research Hospital. The children's parents were interviewed and asked to fill out a data form that solicited information on the patient's demographics, sociodemographic characteristics, education status, family characteristics, parental education level, and family socioeconomic level. After completion of this form, ECI-4 was completed in about 30min by the parents who provided care to the patients. The volunteer control group underwent the same procedure after the parent–caregivers were informed of the study and gave their consent. All scales were evaluated by a child psychiatry consultant.

Inclusion criteriaThe children between the ages of three and five who were diagnosed with, or being monitored for, CMA were included in the study. The control group consisted of age- and sex-matched healthy children who applied to outpatient clinics for routine control.

Exclusion criteriaThe children with incomplete or incorrectly filled-out forms, children who have allergic disease except CMA and children diagnosed with lactose intolerance were excluded from the study. In addition, the children previously diagnosed with psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Diagnosis of CMA was conducted according to the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) guideline for the diagnosis and management of CMA.10 According to this guideline, CMA can be classified as either IgE-mediated, immediate-onset (e.g., urticaria and/or angio-oedema with vomiting and/or wheeze, soon after ingestion of cow's milk) or non-IgE-mediated, delayed-onset (e.g., allergic colitis, atopic eczema). For diagnosis of cow's milk allergy, the recruited patient who has a clear history of immediate symptoms and/or a life-threatening reaction with a positive test for cow's milk protein-specific IgE qualifies for diagnosis without a milk challenge. In all other circumstances, oral food challenge under medical supervision was carried out to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of CMA.

The Early Childhood Inventory-4, developed by Sprafkin and Gadow,11,12 is a scale designed to evaluate the behavioural, emotional, and cognitive symptoms of children between the ages of three and five according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Disorders that rarely occur between the ages of three and five (e.g., schizophrenia) are not investigated in the ECI-4. However, diagnoses such as eating disorders, sleep disorders and AD, which occur more frequently during these ages, are included. The ECI-4 is composed of 108 items that are rated as never, sometimes, often, and nearly always. Sprafkin and Gadow graded the ECI-4 in two different ways: symptom score points and symptom severity points. In the number-of-symptoms scoring, never and sometimes are scored as 0 and often and almost always as 1. Scores obtained for each disorder in the ECI-4 are added. If this overall score is equal to or higher than the number of symptoms required for DSM-IV diagnosis, the symptom criteria score for that disorder is evaluated as yes. In scoring the severity of symptoms, never is scored as 0, sometimes as 1, often as 2, and almost always as 3. Scores obtained from questions are added, and the severity score of the involved disorder is found.11,12 The score's reliability/validity study in Turkey was carried out in general and clinical sample by Başgul et al.13 in children between the ages of three and five. There are two different forms of the scale, one of which is completed by the parents and the other by teacher. In this study, the parent form was used.

Statistical analysisTo detect a difference of 26.5%, power analysis at 80% power and the 0.05 level of significance showed that the present study required a sample size of 40 patients. We recruited 40 patients for the CMA group and 41 patients for the control group.

We performed statistical analysis using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequency and percentage for categorical variables, whereas quantitative data were expressed as median for non-normally distributed data and as mean for normally distributed data. We used the Mann–Whitney U test and student t test for quantitative data to compare two groups (CMA group and healthy control group). The chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variable. We considered a two-sided p<0.05 as statistically significant.

The research protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Inonu University, and all participants gave their written, informed consent.

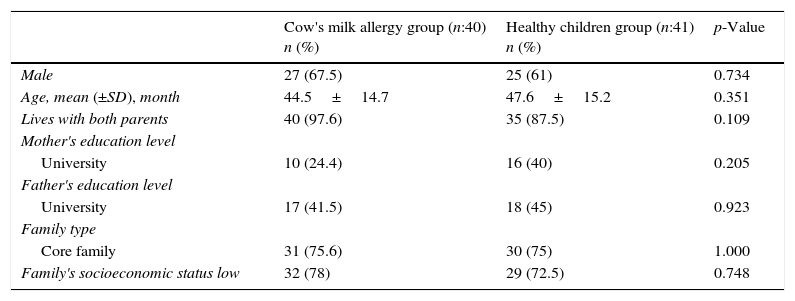

ResultsThe CMA group included 40 children (27 male, 13 female) with mean age, 44.5±14.7 months, and the control group included 41 children (25 male, 16 female) with mean age, 47.6±15.2 months. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, and sociodemographic characteristics (p>0.05). The sociodemographic characteristics of both groups are presented in Table 1.

Sociodemographic features of patients.

| Cow's milk allergy group (n:40) n (%) | Healthy children group (n:41) n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 27 (67.5) | 25 (61) | 0.734 |

| Age, mean (±SD), month | 44.5±14.7 | 47.6±15.2 | 0.351 |

| Lives with both parents | 40 (97.6) | 35 (87.5) | 0.109 |

| Mother's education level | |||

| University | 10 (24.4) | 16 (40) | 0.205 |

| Father's education level | |||

| University | 17 (41.5) | 18 (45) | 0.923 |

| Family type | |||

| Core family | 31 (75.6) | 30 (75) | 1.000 |

| Family's socioeconomic status low | 32 (78) | 29 (72.5) | 0.748 |

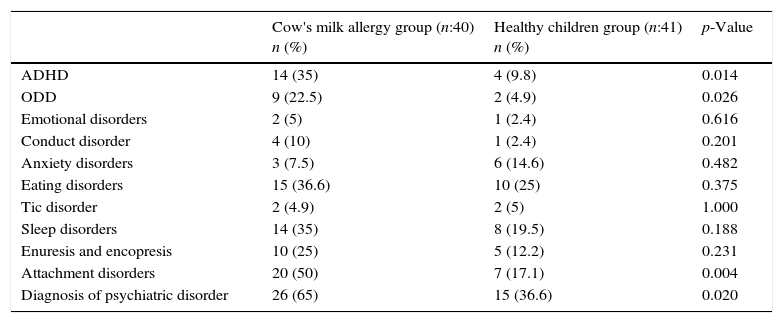

When the groups were compared with respect to whether they received the psychiatric diagnoses measured by ECI-4, it was established that 65% of the group with CMA received at least one psychiatric diagnosis, while 36.6% of the control group received at least one psychiatric diagnosis, with a statistically significant difference (p=0.02). ADHD (odds ratio: 4.9, 95% CI: 1.472–16.856, p=0.006), ODD (odds ratio: 5.6, 95% CI: 1.139–28.128, p=0.026), and AD (odds ratio: 4.8, 95% CI: 1.747–13.506, p=0.004) were found significantly higher compared with the healthy control group. Conduct disorder, eating disorders, sleep disorders, enuresis, and encopresis were found higher in the CMA group although they did not reach statistical significance. The psychiatric diagnoses made with the data obtained from ECI-4 are presented in Table 2.

Diagnoses of psychiatric disorders determined by ECI-4.

| Cow's milk allergy group (n:40) n (%) | Healthy children group (n:41) n (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 14 (35) | 4 (9.8) | 0.014 |

| ODD | 9 (22.5) | 2 (4.9) | 0.026 |

| Emotional disorders | 2 (5) | 1 (2.4) | 0.616 |

| Conduct disorder | 4 (10) | 1 (2.4) | 0.201 |

| Anxiety disorders | 3 (7.5) | 6 (14.6) | 0.482 |

| Eating disorders | 15 (36.6) | 10 (25) | 0.375 |

| Tic disorder | 2 (4.9) | 2 (5) | 1.000 |

| Sleep disorders | 14 (35) | 8 (19.5) | 0.188 |

| Enuresis and encopresis | 10 (25) | 5 (12.2) | 0.231 |

| Attachment disorders | 20 (50) | 7 (17.1) | 0.004 |

| Diagnosis of psychiatric disorder | 26 (65) | 15 (36.6) | 0.020 |

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorders; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.

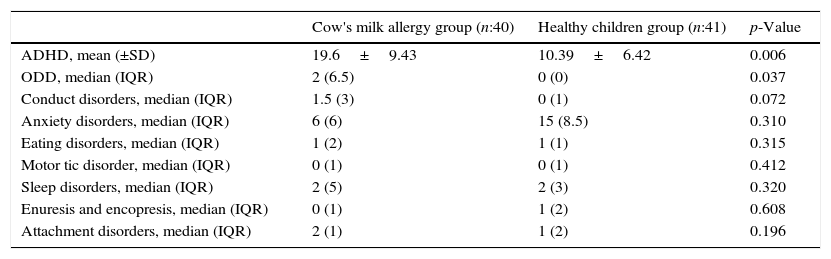

When the groups were compared in terms of psychiatric symptom severity scores, calculated by using ECI-4, ADHD severity (p=0.006) and ODD severity (p=0.037) were found to be higher in the CMA group. Conduct disorder severity was found higher in the CMA group but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.072). Psychiatric symptom severity scores obtained with ECI-4 are presented in Table 3.

Psychiatric symptom severity determined by ECI-4.

| Cow's milk allergy group (n:40) | Healthy children group (n:41) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD, mean (±SD) | 19.6±9.43 | 10.39±6.42 | 0.006 |

| ODD, median (IQR) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 0.037 |

| Conduct disorders, median (IQR) | 1.5 (3) | 0 (1) | 0.072 |

| Anxiety disorders, median (IQR) | 6 (6) | 15 (8.5) | 0.310 |

| Eating disorders, median (IQR) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.315 |

| Motor tic disorder, median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) | 0.412 |

| Sleep disorders, median (IQR) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 0.320 |

| Enuresis and encopresis, median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.608 |

| Attachment disorders, median (IQR) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 0.196 |

IQR, interquartile range.

This study is the first to extensively evaluate psychiatric disorder and psychiatric symptom severity in pre-school children with CMA by using ECI-4. Our results show that rates of psychiatric disorder and psychiatric symptom severity are higher than those of the control group. ADHD, ODD, and AD were especially frequent in pre-school children with CMA.

So far, studies have suggested an association between allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, atopic eczema, food allergy14 and the frequency of ADHD.7,15,16 Studies have shown a closer association between atopic eczema and ADHD.7,17 During the pre-school period, a great majority of patients with atopic eczema also have CMA, or cow's milk triggers exacerbation of the disease.18–20 As in other allergic diseases, Type I and Type IV immunological mechanisms and the cytokines related to these mechanisms play a role in patients with CMA. Limited previous studies have shown that psychiatric disorders such as ADHD are more frequent in patients with allergic diseases (e.g., allergic rhinitis, atopic eczema, food allergy).15,16,21,22 In these studies, two hypotheses have been proposed that attempt to explain why psychiatric disorders, especially ADHD, are frequently seen in atopic disease. The first hypothesis is that Th2, and its cytokines, play the major role in the development of atopic disease such as food allergy. Within this content, a previous immunological study found that dopamine transporters are causally implicated in ADHD and are targets for drugs like methylphenidate. These receptors are abundantly expressed on human T-cells, trigger the selective secretion of immune-regulatory cytokines, like interleukin (IL)-10, and react by activating STAT6, a transcription factor in the immune system's Th2 cells.23,24 In that respect, allergic sensitisation is accompanied by the activation of the typical Th2 response. The second hypothesis regarding the frequency of psychiatric disorders in patients with atopic disease involves the pro-inflammatory mechanism. In this mechanism, children with allergic sensitisation are exposed to increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators released during the atopic response. These inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, and INF-gamma) affect brain development in the pre-school age group, especially infants. These cytokines directly affect the developing areas of the brain (anterior cingulate cortex, prefrontal cortex, corpus callosum, and neurotransmitter system) that control attention, motivation, motor, and cognitive functions. Changes in maturation in these areas are thought to increase the risk of ADHD.25 In our study the frequency of ADHD according to ECI-4 in the children with CMA was higher when compared with the healthy control group. ADHD symptom severity was also found to be higher when compared with the control group.

There is controversy about the association between ADHD and ODD, which have both shared and unique genetic influences.26,27 In the aetiopathogenesis of ODD and ADHD, the same psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms may be playing a role. The fact that ADHD is seen frequently in allergic diseases7,15,16 brings to mind that ODD can also be seen frequently in patients with atopic diseases. Ferro et al.28 found that the symptom of ODD was higher among adolescents with food allergy. In addition to this result, we found that the frequency of ODD is higher in children with CMA when compared with the control group in the current study.

The current study has some limitations. First, the absence of face-to-face psychiatric interviews with the patients and the use of only ECI-4 in diagnosing psychiatric disorders may raise concerns regarding the accuracy of diagnoses in the present study. Our findings need to be supported with studies in which diagnoses of psychiatric disorders are made by face-to-face psychiatric assessments, because the ECI-4 questionnaire is only a screening tool. Second, we could not explain why, of all the psychiatric diseases relevant to this age group, only ADHD, ODD, and AD were seen more often in children with food allergy, specifically CMA. But, more recent data revealed that paediatric patients with allergic disorders had a substantially increased risk of developing ADHD,16,29 and conversely, patients with ADHD had an elevated risk of developing allergic diseases.7,30 Allergic disorders are familial and inherited. Therefore, ADHD and allergic diseases may share common aetiological (genetic or environmental or both) pathways. Third, the number of participants who attended the current study is small, and our findings need to be supported by studies that assess a larger patient population. However, the fact remains that this is the first multi-centre study that extensively assessed psychiatric disorders and the severity of psychiatric symptoms in pre-school children with CMA.

ConclusionTwo thirds of the children with CMA were found to have at least one psychiatric disorder, and this rate was higher than the control group in our study. ADHD, ODD, and AD, diagnosed by ECI-4, were found to be higher in the children with CMA when compared with the control group. Therefore, we suggest that children who are diagnosed with CMA should be questioned for psychiatric disorder symptomatology.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

FundingNo financial support was provided.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.