The EAGLE Project database was analysed to assess the characteristics of patients with severe asthma (SA) who required hospitalisation as a result of an acute episode during the period 1994–2004, and the relationship with asthma severity.

MethodsA total of 2593 clinical records corresponding to an equal number of patients hospitalised for acute asthma (15–69 years), with sufficient information to characterize their asthma severity in agreement with GINA criteria were identified (727 patients with SA compared with 1866 patients with non-severe asthma).

ResultsPatients with SA were older, displayed a greater predominance of female asthmatics, lower antecedents of atopy, and a higher frequency of previous hospitalisations compared with non-severe asthmatics (86.1% vs. 50.5%, p≤0.01). Additionally, SA patients showed more severe exacerbations characterized by acidosis, significant spirometric deterioration, greater length of hospital stay (9.4 days vs. 7.0 days), as well as a higher frequency of intubation (16.8% vs. 2.1%), intensive care unit admission (11.3% vs. 4.9%), cardiopulmonary arrest (5.5% vs. 1.3%), and asthma deaths (2.1% vs. 0.4%) (all p≤0.01) compared with non-severe patients.

ConclusionsThis study suggests that SA patients have greater morbidity and a disproportionate need for health care as a result of more severe exacerbations. However, non-severe asthmatics can also still present acute severe episodes (although with a lower frequency) with risk of life.

Asthma is one of the most common chronic diseases worldwide with an estimated prevalence in the industrialised countries of 10–13% of the population.1 The predominant clinical feature is episodic airway obstruction characterized by expiratory airflow limitation.2,3 In the United States it is responsible for more than 1.5 million Emergency Department (ED) visits; approximately 500,000 hospitalisations; and almost 5000 deaths each year, mostly avoidable.4,5 Additionally, it was estimated that around 30% of asthmatics have required ED treatment during the previous year.1

Recently, authors recommended that the term asthma “severity”‘ should be used to refer to the intensity of treatment required to achieve the control of the disease, after co-morbidities and modifiable factors have been treated.6 Thus, asthma severity is a relatively stable feature which, in the context of the stepwise asthma management approach, changes only slowly over time.7 Asthma can be classified in agreement with the lowest level of treatment required to achieve patient's best level of asthma control, from intermittent or mild forms to other severe forms which can, occasionally, cause death.8 Particularly, severe asthma (SA) is characterized by high anti-asthmatic medication requirements, including short and long-acting beta-agonists, oral or inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as well as other medications.2,3 This subgroup of patients represents approximately 10% of the asthma population, presenting an increased morbidity as well as higher levels of health care utilisation compared with patients with non-severe asthma.9–11 Thus, ED visits, hospitalisations and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions for acute asthma are more frequent in SA patients compared with patients with mild to moderate asthma.12,13 Spanish and Latin-America studies14,15 have shown an underuse of appropriate controller medications in children and adults with asthma, particularly in those patients with SA. Also, SA patients showed a high risk of death from asthma compared with non-severe patients.16 However, these studies did not show data related to the characteristics of asthmatics during the exacerbations of the disease. Therefore, the EAGLE Project database17 was analysed to assess the characteristics of patients with SA who required hospitalisation as a result of an acute episode during the period 1994–2004.

Materials and methodsThe EAGLE project,17 acronym in Spanish of the “Estudio del Asma Grave en Latinoamérica y España” (Severe Asthma study in Latin America and Spain), was promoted by the respective asthma sections of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and the Latin-American Thoracic Society. In this study, we reviewed and identified retrospectively all hospital records for patients (15–69 years of age) admitted with a primary diagnosis of acute asthma (International Classification of Diseases [ICD], Ninth Revision, 493.01 and ICD, Tenth Revision, J45, J46 codes), in nine Spanish (Oviedo, Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, La Coruña and Córdoba) and 10 Latin-American hospitals (Buenos Aires and Rosario, Argentina; San Pablo, Brazil; Santiago, Chile; Bogotá, Colombia; Mexico City, Mexico; Lima, Peru; Montevideo, Uruguay; and Caracas, Venezuela) occurring in the years 1994, 1999, and 2004. Eligible hospitals were required to have more than 200 beds and active EDs and ICUs in the selected years. A case-control design was used. Thus, on the basis of the EAGLE database, we identified patients with SA (cases), defined as those with therapeutic requirements equivalent to levels 4–5 of the Global for Initiative for Asthma (GINA),2 and compared them with those with non-severe asthma (controls) (patients with therapeutic requirements corresponding to levels 1–3 of GINA). The following variables were identified: age, sex, year and month of hospitalisation, allergic status (Prick-test, RAST or others), previous use of controller medications (ICS, short and long-acting beta-agonists, theophylline), previous hospitalisations for asthma, lowest arterial pH during hospitalisation, forced expiratory volume in one second/peak expiratory flow ratio (FEV1/PEF) in the ED, length of hospital stay, admission to the ICU, cardiopulmonary arrest, intubation or mechanical ventilation (MV) during hospitalisation, and in-hospital mortality.

All data were analysed with the SPSS 12.0 for Windows software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Mean values±standard deviations (SD) were calculated for continuous variables. Differences between groups were evaluated using one-way or two-way variance analysis. Chi-square with Yate's correction or Fisher's exact test was used for categorical variables. Finally, Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated with standard formulas. A p value of less than 0.05 using a two-tailed test was taken as significant for all statistical tests.

ResultsA total of 2593 clinical records corresponding to a similar number of hospitalised patients and containing sufficient information to determine asthma severity were audited. Of them, 727 patients were classified as having SA (28% of all hospitalisations; 20% of patients admitted during 1994, 30.2% of asthmatics hospitalised during 1998, and 30.7% of asthmatics admitted during 2004). Most patients were female (70.4%), with a mean age of 42.2±19.5 years old, and a mean FEV1 prior to hospitalisation of 78.2±23.4% of predicted. Finally, Spain accounted for 51.9% of the total sample, and Latin America accounted for 48.1%.

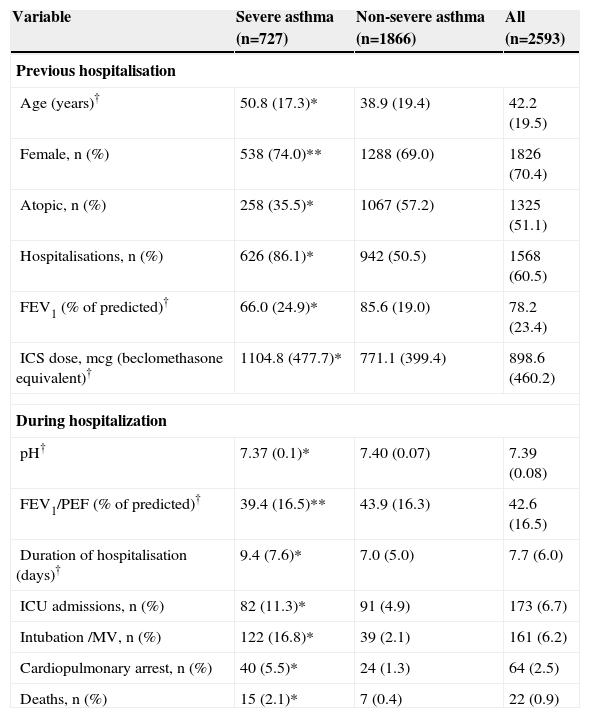

Table 1 shows the characteristics (measured previously and during the hospitalisation) of SA patients compared with those with non-severe asthma. Regarding the variables measured previously to the hospitalisation, compared with non-severe asthmatics, SA patients were older, predominantly female (OR=1.27; 95% CI: 1.05–1.54), with lower antecedents of atopy (OR=0.41; 95% CI: 0.34–0.50) and a higher frequency of previous hospitalisations (OR=6.08; 95% CI: 4.83–7.64). Reasonably, SA patients showed a more intense airway obstruction as well as a greater use of ICS. Concerning the variables measured during the hospitalisation, patients with SA had more severe exacerbations compared with non-severe patients: lower arterial pH and PEF mean values, and longer length of hospital stay, as well as higher rates of intubation/MV (OR=9.41; 95% CI: 6.51–13.7), ICU admissions (OR=2.48; 95% CI: 1.81–3.38), cardiopulmonary arrest (OR=4.46; 95% CI: 2.67–7.46), and in-hospital deaths due to asthma exacerbation (OR=5.59; 95% CI: 2.27–13.77).

Characteristics of all hospitalised patients with severe asthma compared with those with non-severe asthma

| Variable | Severe asthma (n=727) | Non-severe asthma (n=1866) | All (n=2593) |

| Previous hospitalisation | |||

| Age (years)† | 50.8 (17.3)* | 38.9 (19.4) | 42.2 (19.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 538 (74.0)** | 1288 (69.0) | 1826 (70.4) |

| Atopic, n (%) | 258 (35.5)* | 1067 (57.2) | 1325 (51.1) |

| Hospitalisations, n (%) | 626 (86.1)* | 942 (50.5) | 1568 (60.5) |

| FEV1 (% of predicted)† | 66.0 (24.9)* | 85.6 (19.0) | 78.2 (23.4) |

| ICS dose, mcg (beclomethasone equivalent)† | 1104.8 (477.7)* | 771.1 (399.4) | 898.6 (460.2) |

| During hospitalization | |||

| pH† | 7.37 (0.1)* | 7.40 (0.07) | 7.39 (0.08) |

| FEV1/PEF (% of predicted)† | 39.4 (16.5)** | 43.9 (16.3) | 42.6 (16.5) |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days)† | 9.4 (7.6)* | 7.0 (5.0) | 7.7 (6.0) |

| ICU admissions, n (%) | 82 (11.3)* | 91 (4.9) | 173 (6.7) |

| Intubation /MV, n (%) | 122 (16.8)* | 39 (2.1) | 161 (6.2) |

| Cardiopulmonary arrest, n (%) | 40 (5.5)* | 24 (1.3) | 64 (2.5) |

| Deaths, n (%) | 15 (2.1)* | 7 (0.4) | 22 (0.9) |

†Mean (SD). * p<0.0001; ** p<0.01 compared with non-severe asthmatics.

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in one second; ICS=inhaled corticosteroids; ICU=intensive care unit; MV=mechanical ventilation; PEF=peak expiratory flow rate.

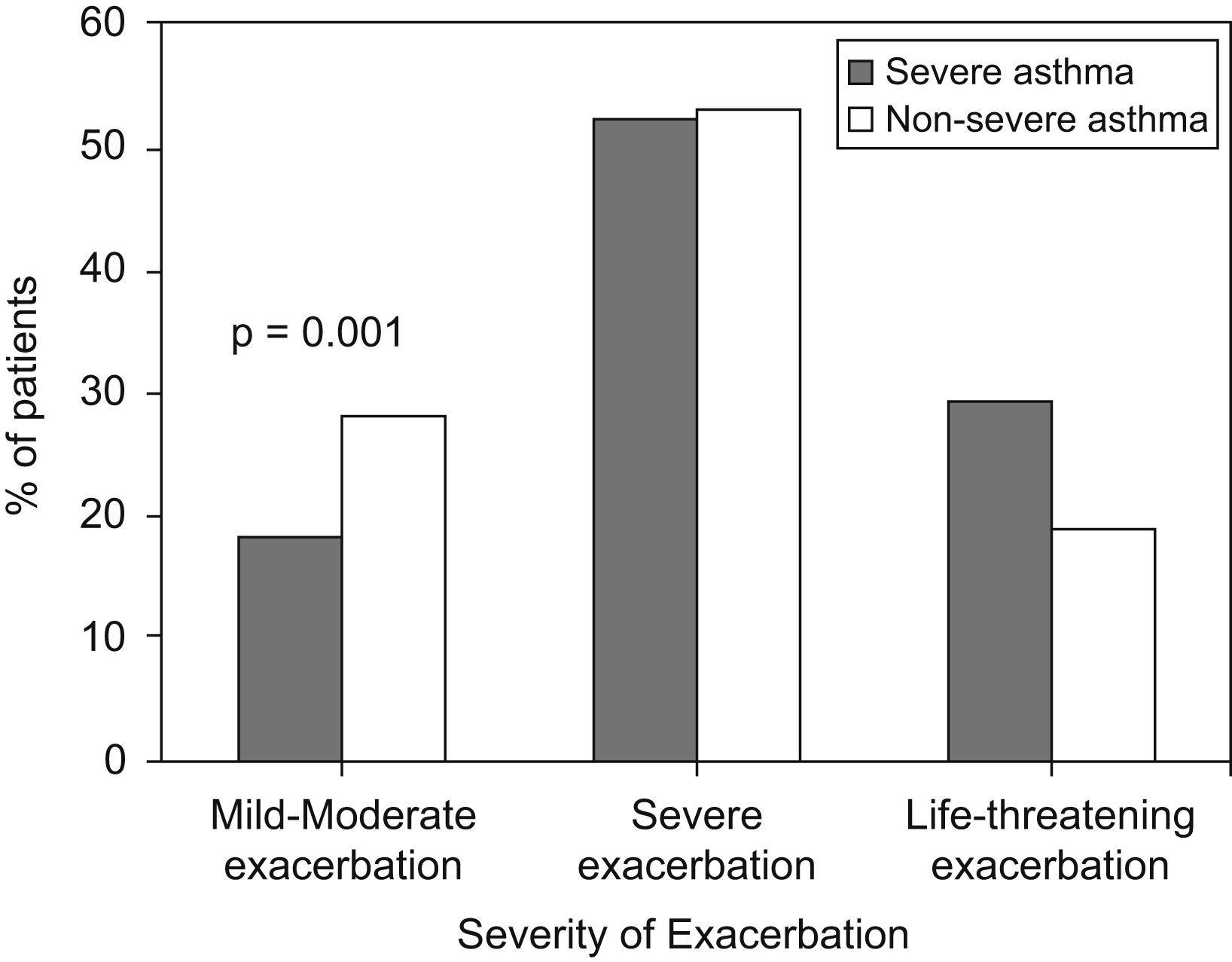

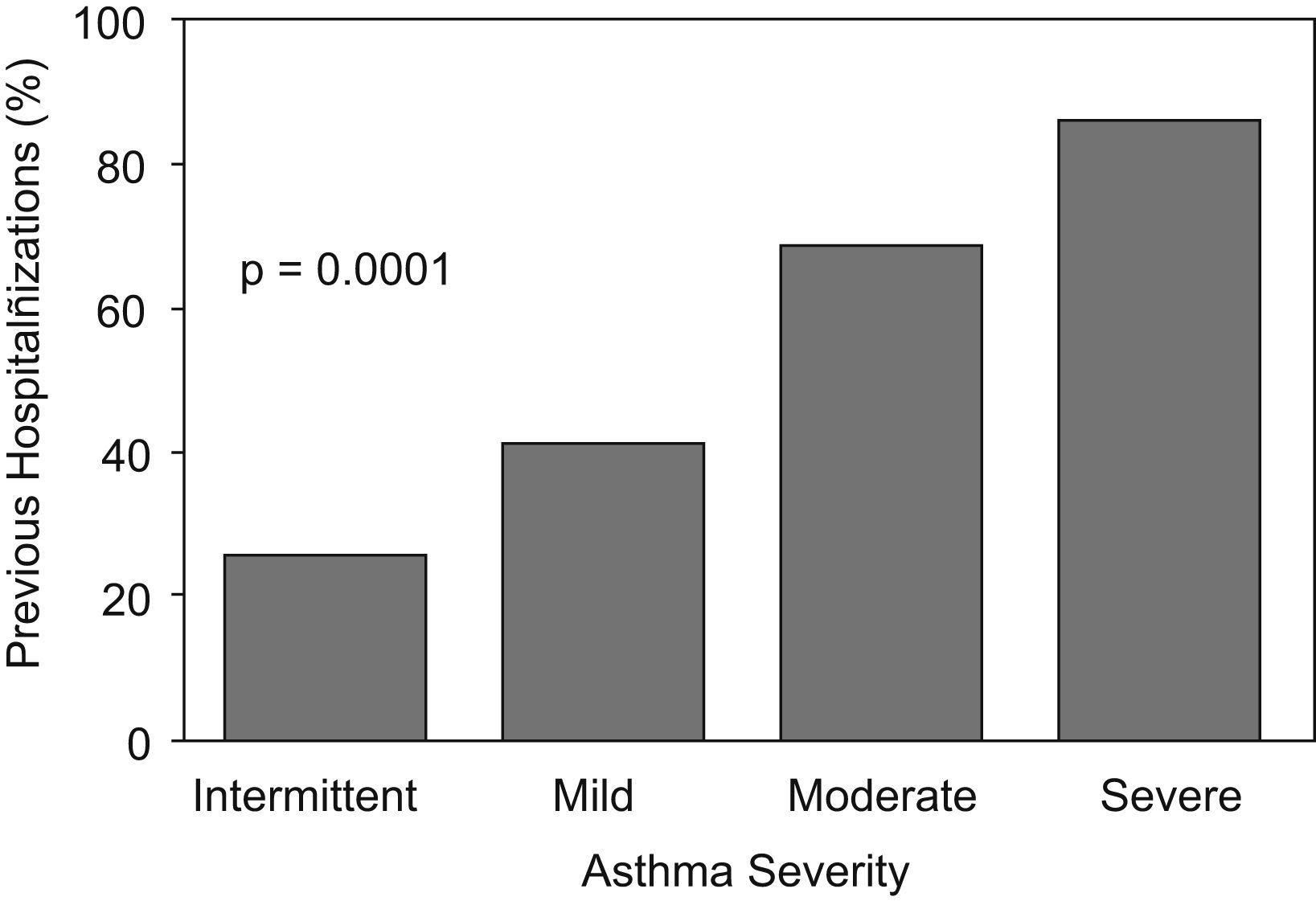

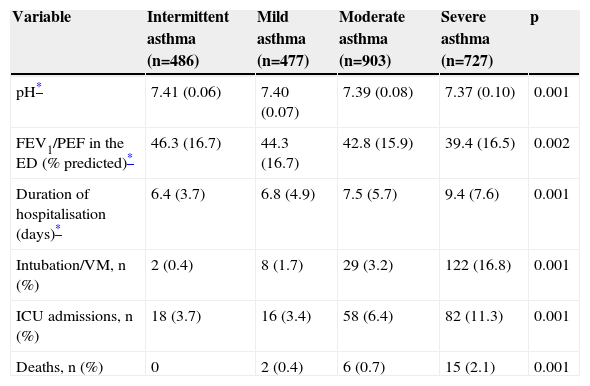

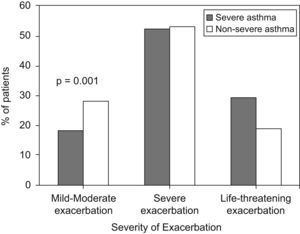

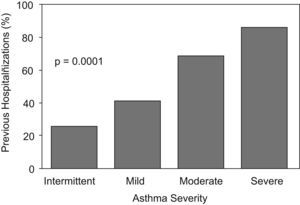

Figure 1 presents the relationship between asthma severity and acute asthma severity. Patients with SA showed a higher frequency of life-threatening episodes (FEV1/PEF<30% of predicted), and a lower rate of mild to moderate asthma exacerbations (FEV1/PEF >50% of predicted) compared with patients with non-severe asthma (p=0.001). A more detailed analysis showed a direct relationship (“dose-effect”) between asthma severity and the level of health care utilisation. Thus, Figure 2 shows that the percent of previous admissions increases in agreement with asthma severity, from 26% in patients with intermittent asthma to 86% in those with SA. The same relationship was found for arterial pH during hospitalisation, FEV1/PEF in the ED, length of hospital stay, rate of intubation or mechanical ventilation (MV) during hospitalisation, admissions to the ICU, and in-hospital mortality (Table 2). In all cases, to greater asthma severity, also acute asthma severity was greater. Except for patients with intermittent asthma, who did not show deaths, the rate of asthma deaths increased with asthma severity. Finally, this was also true for the acidosis level, airway obstruction, length of hospital stay, as well as rate of intubation/MV and ICU admissions.

Relationship between different levels of asthma severity and severity of exacerbations

| Variable | Intermittent asthma (n=486) | Mild asthma (n=477) | Moderate asthma (n=903) | Severe asthma (n=727) | p |

| pH* | 7.41 (0.06) | 7.40 (0.07) | 7.39 (0.08) | 7.37 (0.10) | 0.001 |

| FEV1/PEF in the ED (% predicted)* | 46.3 (16.7) | 44.3 (16.7) | 42.8 (15.9) | 39.4 (16.5) | 0.002 |

| Duration of hospitalisation (days)* | 6.4 (3.7) | 6.8 (4.9) | 7.5 (5.7) | 9.4 (7.6) | 0.001 |

| Intubation/VM, n (%) | 2 (0.4) | 8 (1.7) | 29 (3.2) | 122 (16.8) | 0.001 |

| ICU admissions, n (%) | 18 (3.7) | 16 (3.4) | 58 (6.4) | 82 (11.3) | 0.001 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 6 (0.7) | 15 (2.1) | 0.001 |

The objective of this multinational, multicentre, and retrospective study was to evaluate the relationship between the characteristics of asthmatics who required hospitalisation as a result of an acute episode and the severity of the disease. Thus, we reviewed the EAGLE Project17 database, a study designed to assess the characteristics of hospitalised asthma patients in Spain and Latin America during the period 1994–2004. The present study describes and compares the characteristics of 727 selected patients with SA requiring hospitalisation, with 1866 non-severe asthmatics hospitalised during the same period of time. The data showed an evident association between asthma severity and the severity of exacerbations. Thus, compared with non-severe asthmatics, SA patients displayed more serious exacerbations, with the consequent increase of health care utilisation in terms of a longer duration of hospital stay, and higher rates of ICU admissions (more than twice more frequent), and intubation/MV (more than 9 times more frequent). Also, SA patients showed a higher frequency of cardiopulmonary arrests (4.5 times more frequent) and deaths (almost 6 times more frequent) compared with non-severe asthmatics. Of note, the mortality rate in SA patients was 2.1% compared with 0.9% for all hospitalised patients.

Additionally, the variables measured previously to the hospital admission presented differences between groups. Patients with SA were older, predominantly female, with a lower occurrence of atopy in terms of positive skin tests. Also, most SA patients had experienced previous hospitalisations (86%). Thus, these findings are in agreement with previous studies suggesting that a history of severe acute asthma episodes constitutes one of the most important risk factors of near-fatal or fatal asthma.18,19 This case-control study showed that the characteristics of SA patients are in concurrence with those previously reported by prospective studies. The SARP program12 developed in the United Kingdom and the United States reported older patients, a more pronounced pulmonary function deterioration, and a lower incidence of atopy. On the other hand, the TENOR study20 from the United States showed a predominance of females as well as a higher utilisation of health resources such as admissions, intubation/MV, and ED use in patients with SA. Finally, the ENFUMOSA study21 from Europe characterized SA patients as being predominantly females, with low incidence of atopy and a higher pulmonary function deterioration.

However, an important finding of the present study was that non-severe asthma patients also utilised significant levels of health resources. Thus, 26% of patients with intermittent asthma had experienced previous hospitalisations due to asthma exacerbations, and 4% still required ICU admission during the hospitalisation. In fact, patients with mild asthma showed deaths during hospitalisation suggesting that non-severe asthmatics can experience serious asthma exacerbations, although less frequently.

This study has different weaknesses. Even though it is multinational and multicentred, it was performed in a retrospective way and limited to three discrete time periods. Therefore, there is a possibility that not all charts were located in the studied years, and that continuous data may not show the same trends in acute severe hospitalised asthma. Although we selected a large sample of more than 2500 hospitalised asthmatics from 19 hospital centres from Spain and Latin-American countries, the results are not necessary representative of all hospitalised acute severe asthmatics.

In summary, the findings of this study confirm that SA patients consume disproportionate amounts of health resources as a result of presenting a higher rate of severe asthma exacerbations, compared with non-severe patients. Additionally, data suggest an asthma undertreatment, with the negative results that this fact has in the progression of the disease.22 Nevertheless, non-severe asthmatics also can still present acute severe episodes (although with a lower frequency) with risk of life.

EAGLE InvestigatorsArgentina: R Gené (Hospital de Clínicas, Buenos Aires), LJ Nannini (Hospital General Baigorria, Rosario); Brazil: R Stirbulov (Santa Casa de São Paulo); Chile: R Sepúlveda (Instituto del Tórax); Colombia: I Solarte (Fundación Neumológica Colombiana, Bogotá); Mexico: J Salas (Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias, Ciudad de México); Peru: M Tsukayama (Clínica Ricardo Palma, Lima); Spain: J Armengol (Hospital de Terrassa), S Bardagí (Hospital de Mataró), MT Bazús (Instituto Nacional de Silicosis, Oviedo), J Bellido (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona), A J Cosano (Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba), A. Lopez-Viña (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), E Martinez Moragón (Hospital de Sagunto), M Perpiñá (Hospital La Fe, Valencia), V Plaza (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona), G Rodriguez-Trigo (Hospital Juan Canalejo, La Coruña), J Sanchis (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona); Uruguay: L Piñeyro (Hospital Maciel, Montevideo), GJ Rodrigo (Hospital Central de las Fuerzas Armadas, Montevideo); Venezuela: G Levy (Hospital Universitario, Caracas).

Funding and conflicts of interestThis study was supported by AstraZeneca, Spain as a part of the Programa de Investigación Integrada (PII) del Área de Asma de la SEPAR (Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica). Astra-Zeneca was not involved in the data collection and interpretation and redaction of the manuscript. No financial or other potential conflicts of interest exist.