Egg allergy is an adverse immune-system reaction of an IgE-mediated type, which can happen in children after egg intake and several times after their first egg intake.

ObjectivesCompare the results of the oral egg-challenge test in two groups of egg-sensitised children, with and without prior intake.

Patients and methodsRetrospective study of two egg-sensitised groups (72 subjects).

Group 1: 22 children without prior egg-intake.

Group 2: 50 children with a clinical history of adverse reactions after egg intake.

Skin prick tests, egg-white specific IgE (sIgE) and yolk specific IgE, were performed on all children. The oral egg-challenge tests were performed after a period of egg-avoidance diet and when egg-white specific IgE levels were lower than 1.5KU/L.

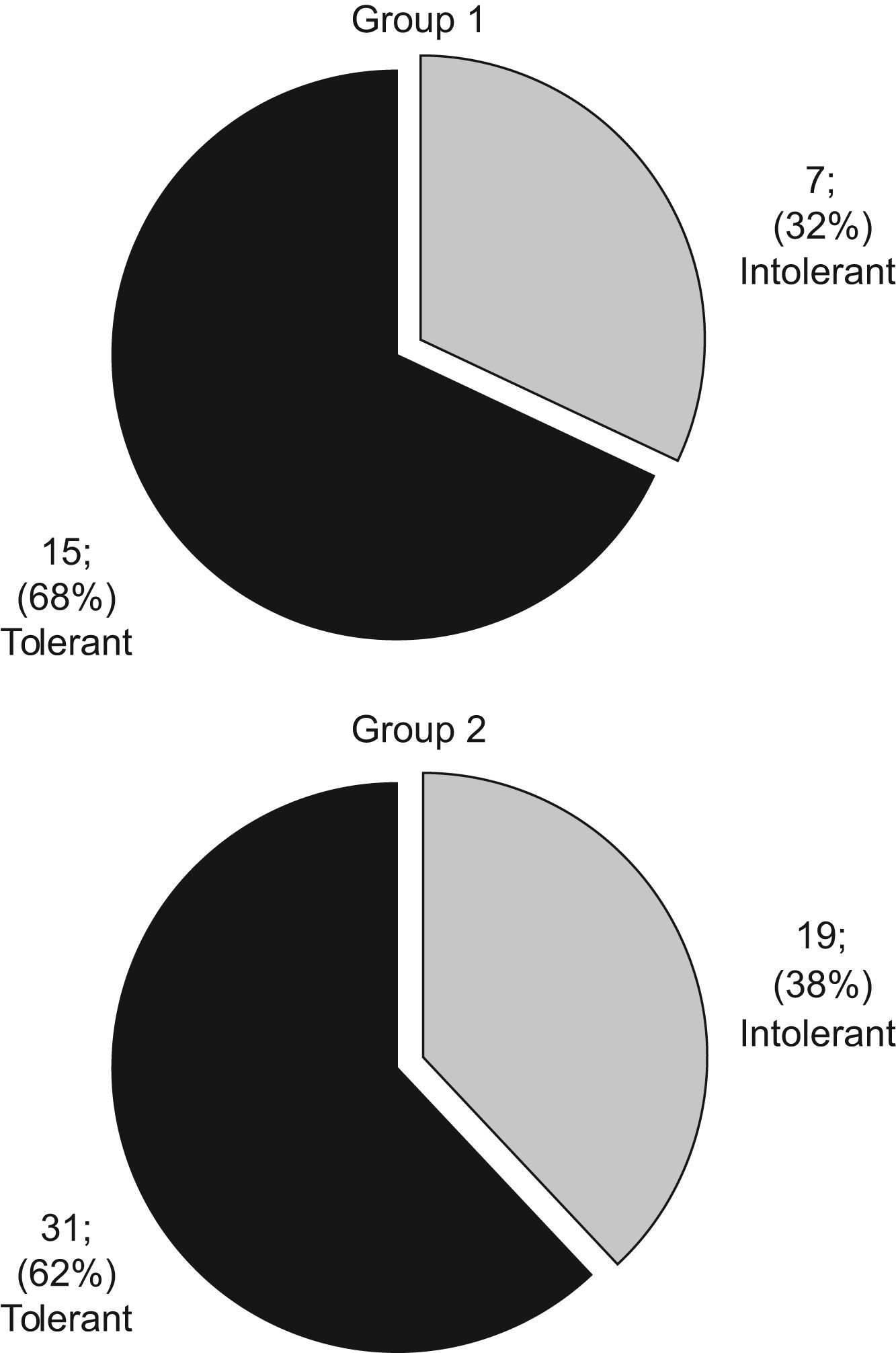

Results31.8% of the children in Group 1 did not tolerate egg-intake whereas 38% of the children in Group 2 did not tolerate egg-intake. Egg-avoidance periods lasted 19.5 and 18 months, respectively.

Egg-white specific IgE levels went down in both groups after an egg-avoidance diet. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups and the positivity of oral egg-challenge test.

ConclusionsNo statistically significant differences were found in the behaviour of the two groups studied.

Given the high risk of adverse reactions, it was recommended that any egg-introduction tests were to be performed in a hospital environment on the children who were sensitised to hen’s egg (including children without prior egg intake).

Egg is a foodstuff that often produces allergies in early childhood due to its high protein-content.

Egg allergy is an adverse reaction that has an immuno-pathogenic mechanism. Egg allergy prevalence is still unknown. It ranges from 0.2% to 7% in the meta-analysis by Rona et al.1 According to the outcome of the study “ALERGOLOGICA 2005”2 carried out by SEAIC, the most frequent allergy-producing foods in children younger than seven years of age in Spain are egg; milk; fish; and nuts. In older children the culprit is vegetables.

Egg-sensitisation in children without prior egg-intake has often been detected in tests for atopic dermatitis (AD) and cow’s milk-protein allergy.

Several IgE-mediated reactions 3–6 were described after first intake, which points to a prior sensitisation that can have been produced by different means; either by intrauterine (in utero) sensitisation, due to the fact that egg-specific IgE 7 has been found in cord blood, or by means of breast-feeding.8 A third means could be objects that have been contaminated with egg particles, such as cooking equipment and toys.

There is every likelihood that children who suffer from egg allergy will have a history of AD.9–12 This pathology often begins in the second or third month of life when the baby is being breast-fed. That is to say that it happens during lactation, and thus there is no relationship to egg-intake.5

Once there is an indication of immediate egg allergy from a patient’s preliminary case history, egg sensitisation must be demonstrated. This can be achieved by skin prick tests (SPT) and/or in vitro tests. The SPT is the best means of diagnosing egg allergy owing to its high sensitivity (73–100%), although it has a lower specificity. Egg SPT negativity might rule out egg allergy in most cases due to its highly negative predictive value.(86%–91%).3,13,14

Another means to determine egg sensitisation is egg-specific IgE antibodies determination test.(RAST, CAP).

Some studies have attempted to determine cut-off points for specific IgE levels in order to predict clinical reactions and thus avoid oral challenge tests which are highly likely to produce a positive outcome.9,13,15

Children who have been diagnosed as suffering from egg allergy are checked regularly so as to determine the moment when tolerance appears. Egg-white specific IgE is determined and afterwards, levels of sensitisation are studied. A positive development to tolerance is shown in the event of lower levels. In a long-term retrospective study, 37% of egg-allergic children showed tolerance at the age of 10 years.16 In a prospective study, half of the children showed tolerance between the ages of 4 and 4.5 years (18% of the subjects after a period of two years, 52% of the subjects after 48 months and 66% of the subjects after 60 months).17

Few studies have been found dealing with the clinical management of egg-sensitised children without prior egg intake. Among them, there is a noteworthy study by Caffarelly et al.3 according to which, SPTs for egg can be useful to predict which children will have a reaction on their first egg exposure. Boissieu et al.4 have observed that tolerance develops around the age of three years in egg-sensitised children without prior egg-intake. According to Monti et al.5 children with AD who have never eaten eggs can display reactions after their first intake. In addition, Dieguez et al.6 have proven that milk-sensitised children have a higher risk of egg allergy. Early diagnosis is necessary and the SPT is a very useful tool for diagnosing immediate IgE egg reactions on the first known exposure. In this study conducted on children with cow’s milk allergy, 62.5% of the subjects without prior egg intake were found to be egg sensitised in SPTs. In addition, the challenges were positive in 56.9% of the children who were egg sensitised without prior egg intake.

Many of the egg sensitised patients can been found early before their egg intake because we routinely check egg sensitisation in children with AD or children with allergy to cow’s milk. In our practice the oral egg challenge is conducted when cut-off values of egg white-specific IgE are 1.5KU/L.

The main objective of this study has been to compare the results of the oral challenge test in two groups of egg-sensitised children with and without prior egg intake after a period of egg avoidance.

MethodsPatientsThis is a retrospective study comparing two groups of egg-sensitised children after a period of egg avoidance, who underwent an oral egg challenge test between 01/2007–09/2007(9 months).

72 egg-sensitised children (44 boys, 28 girls) were studied, median age was 2.5 months (13–108).Skin prick tests, egg-white specific IgE, yolk specific IgE were performed in all children.

Serum egg white-specific IgE was tested (every six months) until values under 1.5KU/L were reached. At this point the oral challenge test was performed.

The patients were separated into two groups:

Group 1: (22 children) Egg had not been introduced into their diet (no evidence of prior egg intake). Egg sensitisation was detected in an atopy test and/or cow’s milk allergy test.

Group 2: (50 children) They were studied due to a clinical history of possible allergic reaction after egg intake.

Full features of the sample are set out in Table 1.

Characteristics of the whole population

| Features | Study population | n=72 | |

| Total number of patients | 72 | ||

| Sex: | Male | 44 | |

| Female | 28 | ||

| Diagnostic Age (months): | 10(4–24) | ||

| Family history of atopy | |||

| Positive: | 34 | ||

| Negative: | 38 | ||

| Positive egg skin prick test: | 72 | ||

| History of atopy (without egg sensitisation) | |||

| Negative: | 20 | ||

| Positive: | |||

| AD | 16 | ||

| BHR | 4 | ||

| AD+BHR | 12 | ||

| Food (fish) | 1 | ||

| Milk | 8 | ||

| AD+Milk | 9 | ||

| AD+BHR+Milk | 2 | ||

| Sensitisation to milk | |||

| Negative: | 53 | ||

| Positive: | 19 | ||

| Egg-intake before avoidance | |||

| Negative: | 22 | ||

| Positive: | 50 | ||

| Reactions with intake | |||

| Skin | 35 | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | ||

| Skin+respiratory | 2 | ||

| Skin+Gastrointestinal | 9 | ||

| Age when challenge was performed (months): | 28.5 (13–108) | ||

| Period of egg-avoidance (months): | 19 (2–100) | ||

| Total IgE UI/L (median) | 29 (10–1733) | ||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L) | Median: 0.63 (0–15) | Mean: 1.77 (sd 2.91) | |

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L) | Median: 0.3 (0–1.51) | Mean: 0.42 (sd 0.3) | |

| Initial yolk IgE (kU/L) | Median: 0.08 (0–3.23) | Mean: 0.26 (sd 0.55) | |

| Final yolk IgE (kU/L) | Median: 0.06 (0–0.46) | Mean: 0.11 (sd 0.11) | |

| Results of oral egg-challenge test | |||

| Negative (tolerated egg-intake): | 46(64%) | ||

| Positive (not tolerated egg-intake): | 26(36%) | ||

| Negative oral egg-challenge test | |||

| Age when challenge was performed (months): | 26.5(13–108) | ||

| Period of egg-avoidance (months): | 15.5(2–100) | ||

| Median | |||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 0.42(0–15) | ||

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 0.27(0.04–1.51) | ||

| Positive oral egg-challenge test | |||

| Age when challenge was performed (months): | 37.5(17–97) | ||

| Period of egg-avoidance (months): | 27(2–85) | ||

| Median | |||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 1.4(0–13) | ||

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 0.49 (0.07–1.29) | ||

Values between brackets reflect the median rate.

Abbreviations: sd=mean standard deviation; AD=atopic dermatitis; BHR=bronchial hyper-responsiveness; SPT=skin prick test.

Antihistamine use was suspended during the 7 days that preceded the test. (antihistamines inhibit SPTs).

Standard food allergens were used (Bial-Aristegui laboratories, Bilbao, Spain) including: cow’s milk, alpha-lacto albumin, beta-lacto globulin, casein, whole egg, ovalbumin, ovomucoid, egg white, yolk, wheat, corn, rice, gluten, fish, chicken, veal, almond, soy and sweet potato. Pneumo-allergens included dermatophagoides pteronyssimus, phleum, and cat epithelium (given its widespread existence in our environment). Histamine (10mg/dl) and glycerol saline served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The results were read 15min after the allergen was administered. A mean wheal diameter measuring 3mm or more, and greater than the positive control was considered positive.

Specific IgEThe specific-IgE antibodies for egg white, yolk and other allergens were measured in serum by means of Pharmacia CAP System (Pharmacia Diagnostics, Uppsala, Sweden) in accordance with the usual methods regularly used by the Hospital Vall d' Hebron biochemistry department.

Oral challenge test with cooked eggThe challenge was performed in the Paediatric Allergy Department with suitable equipment available to treat possible allergic reactions, should the subjects display any. Upon admission the children were asymptomatic and had not taken certain medications such as antihistamines (7 days prior to the challenge); short-acting bronchodilators (12 hours prior to the test); or oral corticosteroids (3 days prior to the test). As a test dose, a cooked egg was administered, starting with a labial food challenge. If no adverse reactions were observed, 1 gram, 5 grams and 15 grams respectively were administered to non-responders every 30min. Provided that no clinical reactions appeared, parents were given a piece of paper to mark down late onset reactions at home during the following three days (such as affect on skin, respiration and digestive system). It was recommended that they introduce egg into the child’s diet gradually. The gradual introduction is to commence one week following the oral challenge test and to continue for 3 months. Six months after the challenge, the patients were clinically checked once again in order to assess their final egg tolerance. The challenge was scored negative if no clinical reactions were observed when the child ingested egg after 6 months.

StatisticsMann-Whitney’s non-parametric test was used to compare quantity variables (between both groups and the results of the oral challenge test), such as total IgE, specific IgE, period of egg-avoidance, and age of children when the challenge was performed. Chi-square test was used to compare quality variables, such as sex, family history of atopy, AD, sensitisation to milk, and other quality variables between both groups and the results of the oral challenge; p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

The SPSS 12 program for Windows was used to perform statistical calculations.

ResultsAll of the 72 patients (44 male/28 female) had initial positive egg SPTs, median diagnostic age of 10 months (4–24). Among the patients’ clinical symptoms, it is worth noting that 72.2% had a personal history of atopy (without egg sensitisation), of these 30.7% suffered from AD, 17.3% had AD plus milk sensitisation and 23% suffered from AD plus bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR, which was diagnosed based largely on symptom patterns such as wheezing, coughing, breathlessness typically manifested with activity limitation and nocturnal symptoms/awakenings).Of all the participating patients, 22 (30.5%) had not noticeably ingested egg before (Group 1) and 50 (69.5%) had displayed reactions after egg intake (Group 2).The above-mentioned 50 children with egg intake displayed the following symptoms:

8% gastrointestinal (GI)

70% only skin (urticaria)

22% anaphylactic

- a)

18% skin symptoms plus GI (vomiting)

- b)

4% skin and respiratory (rhinitis)

- a)

Median egg avoidance period of 19 months (2–100).

The initial median level of total IgE was 29UI/L (10–1733).

The initial median level of egg white-specific IgE was 0.63kU/L (0–15), the mean level was 1.77 (sd 2.91).

The final median level of egg white-specific IgE was 0.3kU/L (0–1.5), the mean level was 0.42 (sd 0.3).

Full features of both groups are set out in Table 2.

Characteristics of the population stratified by prior egg-intake

| Features | Group 1 (No prior egg-intake) | Group 2 (Prior egg-intake) | p Value | |

| (n=22) | (n=50) | |||

| Sex: | Male | 14 | 30 | |

| Female | 8 | 20 | ||

| Diagnostic age (months): | 7 (4–15) | 11 (5–24) | NS | |

| Family history of atopy: | ||||

| Negative: | 10 | 28 | NS | |

| Positive: | 12 | 22 | NS | |

| Egg SPT positivity: | 22 | 50 | ||

| History of atopy (without egg sensitisation): | <0.001 | |||

| Negative: | 20 | |||

| Positive: | 22 | 30 | ||

| AD | 4 | 12 | 0.043 | |

| BHR | 4 | |||

| AD+BHR | 4 | 8 | ||

| Milk | 7 | 1 | ||

| AD+Milk | 5 | 4 | ||

| AD+BHR+Milk | 2 | |||

| Food (fish) | 1 | |||

| Milk sensitised: | <0.001 | |||

| Negative: | 8 | 45 | ||

| Positive: | 14 | 5 | ||

| Egg-intake prior to avoidance: | ||||

| Negative: | 22 | |||

| Positive: | 50 | |||

| Reaction with intake: | ||||

| Skin | 35 | |||

| Gastrointestinal | 4 | |||

| Skin+Respiratory | 2 | |||

| Skin+Gastrointestinal | 9 | |||

| Age when challenge was performed (months): | 25.5 (13–79) | 29.5 (16–108) | NS | |

| Egg-avoidance period (months): | 19.5 (7–72) | 18 (2–100) | NS | |

| Total IgE UI/L (median) | 22 (10–810) | 34.6 (10–1733) | NS | |

| Median: | ||||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L) | 0.94 (0–15) | 0.61 (0–13) | NS | |

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L) | 0.36 (0.09–1.29) | 0.3 (0.5–1.5) | NS | |

| Initial yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.01 (0–1.36) | 0.16 (0–3.23) | NS | |

| Final yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.07 (0–0.46) | 0.06 (0–0.39) | NS | |

| Mean: | ||||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L) | 2.18 (sd 3.54) | 1.59 (sd 2.61) | NS | |

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L) | 0.43 (sd 0.31) | 0.42 (sd 0.32) | NS | |

| Initial yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.15 (sd 0.31) | 0.31 (sd 0.63) | NS | |

| Final yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.09 (sd 0.1) | 0.12 (sd 0.12) | NS | |

| Results of oral egg-challenge test | NS | |||

| Negative (tolerated egg-intake): | 15 (68.2%) | 31 (62%) | ||

| Positive (not tolerated egg-intake): | 7 (31.2%) | 19 (38%) | ||

| Negative oral egg-challenge test | ||||

| Median | ||||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 1.97 (sd 3.81) | 0.86 (sd 0.94) | ||

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 0.35 (sd 0.24) | 0.35 (sd 0.3) | ||

| Initial yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.15 (sd 0.34) | 0.15 (sd 0.16) | ||

| Final yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.07 (sd 0.06) | 0.11 (sd 0.13) | ||

| Positive oral egg-challenge test | ||||

| Median | ||||

| Initial egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 2.63 (sd 3.11) | 2.79 (sd 3.82) | ||

| Final egg-white IgE (kU/L): | 0.61 (sd 0.4) | 0.53 (sd 0.32) | ||

| Initial yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.137 (sd 0.2) | 0.58 (sd 0.96) | ||

| Final yolk IgE (kU/L) | 0.13 (sd 0.16) | 0.14 (sd 0.11) | ||

Values between brackets reflect the median rate.

Abbreviations: sd=mean standard deviation; AD=atopic dermatitis; BHR=bronchial hyper-responsiveness; SPT=skin prick test; NS=nonsignificant.

It is worth mentioning that in Group 1 the median egg-avoidance period prior to the challenge was 19.5 months (7–72) and the median age when tolerance appeared was 25.5 months (13–79).The seven children (31.8%) who did not tolerate egg intake are included in this group. Mostly skin reactions were elicited from children, within 2 hours following their egg challenge. The mean serum sIgE levels of those children with a positive challenge were:

Mean egg-white IgE (kU/L) initial: 2.63 (sd 3.11); final: 0.61 (sd 0.40).

Mean yolk IgE (kU/L) initial: 0.137 (sd 0.2); final: 0.13 (sd 0.16).

The remaining 15 children (68.2%) in Group 1 tolerated egg intake without any reactions during the challenge. They reported egg tolerance 6 months after the challenge as well.

The mean serum sIgE levels (with negative challenge) were:

Mean egg-white IgE (kU/L) initial: 1.97 (sd 3.81); final: 0.35 (sd 0.24).

Mean yolk IgE (kU/L) initial: 0.157 (sd 0.34); final: 0.07 (sd 0.06).

The initial and final mean levels of egg-white specific IgE are represented in Figure 1 (for patients in Group 1).

In Group 1 no statistically significant differences were found between total IgE; specific IgE for yolk; initial egg-white and final egg-white levels with a positive or negative response to the oral egg challenge. Neither were there any statistically significant differences between the results of such a test and other features of the sample. However, statistically significant differences were found when comparing the response to the egg challenge and the period of egg avoidance (p=0.004).

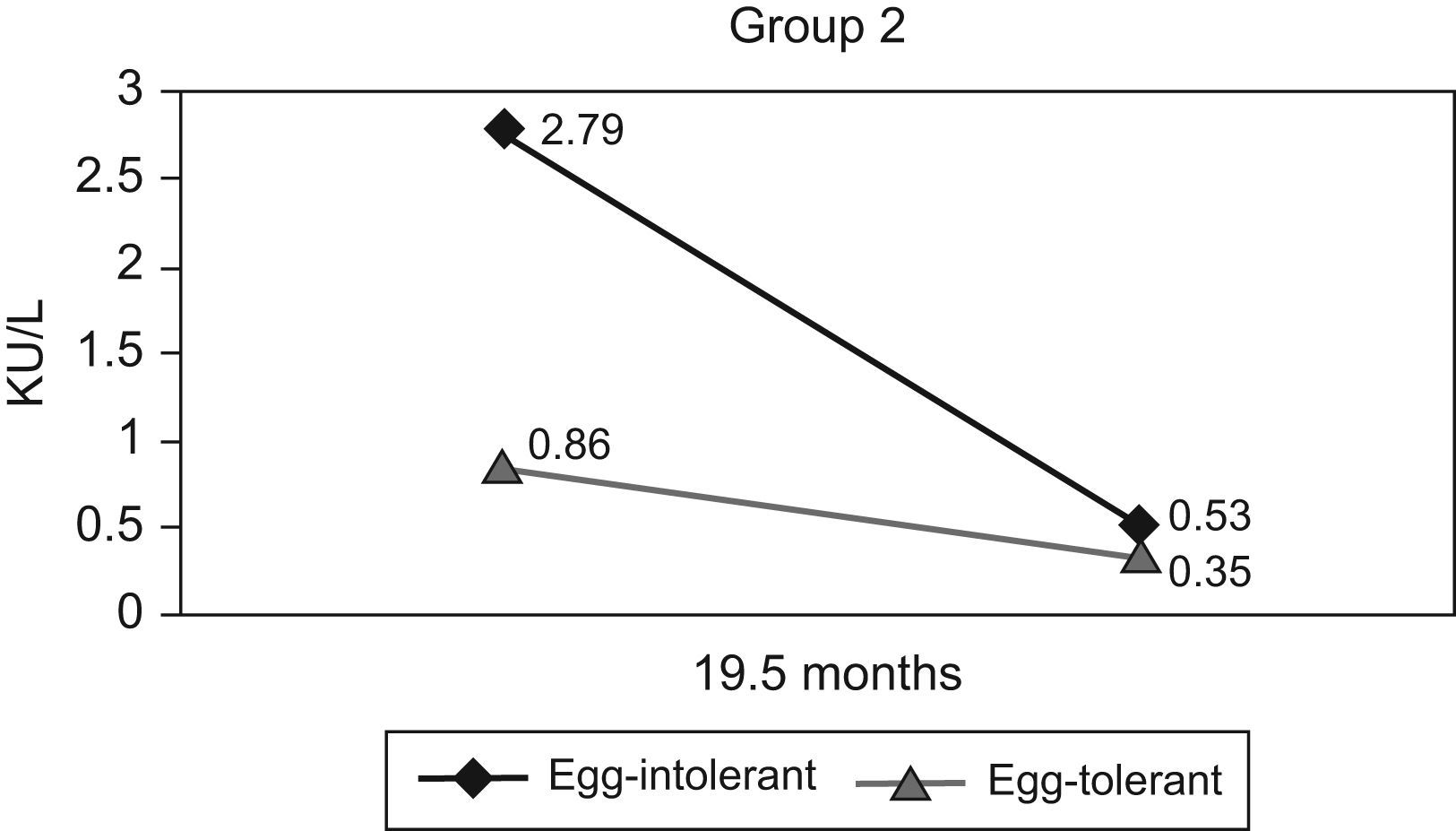

In Group 2, it is worth noting that some children displayed reactions before the usual age for egg introduction into their diet, primarily due to accidental intake. The median egg-avoidance period before challenge lasted 18 months (2–100). On initial analysis, some children had egg-white specific IgE values under 1.5kU/L, which accounted for the fact that sometimes the egg-avoidance period was quite short (from 2 to 4 months). The 19 children (38%) in Group 2 displayed reactions after egg intake (positive oral egg challenge) which were similar to Group 1, mostly relating to skin, within 2 hours following the egg challenge. These children had mean sIgE levels of:

Mean egg-white IgE (kU/L) initial: 2.79 (sd 3.82); final: 0.53 (sd 0.32).

Mean yolk IgE (kU/L) initial: 0.58 (sd 0.96); final: 0.14 (sd 0.11).

The remaining 31 children (62%) in Group 2 tolerated egg intake during the challenge as well as 6 months later. These children’s mean sIgE levels were:

Mean egg-white IgE (kU/L) initial: 0.86 (sd 0.94); final: 0.35 (sd 0.30).

Mean yolk IgE (kU/L) initial: 0.15 (sd 0.16); final: 0.11 (sd 0.13).

The mean initial and final egg-white specific IgE levels of the patients mentioned above are set out in Figure 2.

In Group 2, statistically significant differences were found regarding the patients’ response to the challenge and the initial (p=0.012) and final (p=0.017) egg-white specific IgE levels. No statistically significant differences were found when comparing total IgE, initial and final sIgE for yolk or other records in the history of atopy (A.D., BHR, milk sensitisation) with a positive or negative response to the challenge.

Challenge global results for Groups 1 and 2 can be seen in Figure 3.

No statistically significant differences were found between Groups 1 and 2 when comparing their response to the oral challenge, their total serum IgE, initial and final sIgE for yolk and egg-white, age when challenge was performed, and period of egg-avoidance. Regarding the comparison between the two groups and personal history, statistically significant differences were found in their personal history of atopy (without egg sensitisation) (p<0.001) and specifically, in their milk sensitisation (p<0.001) and AD (p=0.043).

When assessing the response to the oral challenge in all samples and without dividing it into two groups, the only statistically significant differences found were those linked to initial (p=0.016) and final (p=0.004) sIgE levels for egg-white; age when oral challenge was performed (p=0.049); and period of egg avoidance (p=0.032).

DiscussionAllergic reactions to egg intake (urticaria, re-exacerbation of AD, bronchospasm, rhinoconjunctivitis, vomiting, diarrhoea or anaphylaxis) can be displayed by children after their first exposure.3–6 Therefore, it is on occasions rather difficult to determine whether the child is allergic to egg or just egg sensitised when the patient has never eaten egg and is egg SPT positive and/or egg-white or yolk specific IgE positive. The “Gold Standard” is the standardised oral challenge test. However, performing the oral challenge test is time-consuming (over 4–6 hours with an allergist) and it places the patient at risk for an allergic reaction during the testing. Some authors 9,13,15,18 claim that performing an oral challenge test as a diagnostic tool can be unnecessary when there is an increase in serum specific IgE above certain levels. The IgE predictive levels indicating a positive reaction to egg intake vary according to different studies 15,18,19: Sampson 6kU/L (95%); Boyado>0.35kU/L (90%); Osterballe and Bindslev-Jensen 1.5kU/L (95%); Celik-Bilgili 10kU/L (95%).

Some authors such as Monti et al.5 recommend that patients with AD with no prior egg intake and whose SPTs and/or positive sIgEs levels were higher than the cut-off values established for the whole population should undergo the oral challenge test in a hospital environment.

As in other studies we have also found reactions in children without prior egg-intake exposure. In our study, 32% of the children who had never ingested egg displayed clinical reactions after first intake (Group 1). We have also confirmed that egg-white sIgE levels and yolk sIgE levels decrease after a period of avoidance. Our study outcome aims at a decrease in the cut-off values, which would improve the response to the oral challenge. On the other hand, it would delay the introduction of a basic food to a child’s diet. When the cut-off point for egg-white sIgE was lowered to <0.5kU/L in our sample, we observed that 28% (4 children) in Group 1 and 28% (10 children) in Group 2 did not tolerate egg intake, as opposed to 32% and 38% of children when the cut-off was 1.5kU/L. This would suggest that children who displayed a reaction after egg intake (Group 2) had a 10% decrease in positive reactions to the oral challenge, even after lowering the cut-off point, which would justify a delay in the challenge for this group. In Group 1 lowering the cut-off meant only a 4% decrease in positive reactions, which would not justify a delay in the challenge.

Among our study limitations we can highlight the fact that this was a retrospective study, and the patients without clinical reactions were not subjected to an oral challenge test at the age when egg is introduced. It is also likely that some of them would have tolerated egg intake from the beginning. Moreover, it is hard to say whether our sample is completely representative of our population, given the fact that there are no accurate data as to the prevalence of egg allergy. In addition, we only included our patients for a period of nine months. Therefore, we believe that the children in Group 1 (without prior egg intake) should undergo an oral challenge test at the age when egg is normally introduced into their diets to confirm whether the patient is allergic or not.

No statistically significant differences were found in the behaviour of the two groups as to the oral egg challenge after a period of avoidance. The cut-off point for egg-white specific IgE (1.5kU/L) should be lowered to establish a less hazardous oral challenge, especially for the children in Group 2. The egg-white sIgE and yolk sIgE levels diminished after a period of avoidance in both groups. We have confirmed that the children without prior egg intake (no known exposure) can be sensitised and thus display clinical reactions after egg intake. As a result, we recommend that any egg introduction test should be performed in a hospital environment with suitable equipment to treat possible adverse reactions.

The management of children in Group 1 who displayed clinical reactions and did not tolerate egg intake (positive challenge) should be the same as the children in Group 2. These findings point to the need for further studies to assess the clinical management of egg-allergic children and especially of those who have never ingested it.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.