Scabies is observed with relatively high frequency in Allergy and Dermatology clinics in developing countries where poor sanitary conditions are prevalent and increasingly in some areas of the world with increased immigrant populations. Since the immunological response to scabies mites includes the production of IgE class antibodies to Sarcoptes scabiei allergens which cross-react with Dermatophagoides major allergens Der p 1 and Der p 2, positive immediate-type skin tests to house dust mite extracts should be interpreted cautiously. Additionally, scabies should be included routinely in the differential diagnosis of itchy rashes in patients living in those areas.

Scabies is a highly contagious skin disease of worldwide distribution caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, characterised by generalised intense pruritus. Approximately 300 million cases of this ailment occur every year.1 The infection occurs sporadically in developed countries where it is present as institutional outbreaks in hospitals, schools, nursing homes, prisons, and long-term care facilities. The recent upsurge of immigration from less developed areas into Europe, North America, and other industrialised countries carries the risk of an increase of scabies in those regions.

It is known that disadvantaged populations in which overcrowding and poverty are the rule, and immunologically compromised individuals (for example, HIV-infected patients) are particularly at risk. Scabies is endemic in developing and tropical areas of the world.2 In resource-poor urban and rural communities its prevalence may be as high as 10% of the general population and 65% of the children.3,4 It is transmitted by close personal contact or indirectly via fomites (clothing or bed sheets).5

The morbidity of scabies is enhanced by secondary bacterial infections of the skin, especially by Group A Streptococcus and Staphylococcus aureus, which are responsible for associated clinical pictures such as cellulitis, lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy, and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis.6

Recently we received in our Allergy Clinics a male patient with a severe form of scabies, with numerous popular lesions in the skin and nodular lesions in the genitalia that met the clinical criteria of Norwegian scabies. After reviewing the current literature on scabies and crusted scabies we became aware of the interesting immunological interactions between scabies mites (SM) and domestic mites (HDM) and the importance of scabies infestations for the practicing clinician, especially those working in allergology and dermatology in areas of the world with endemic scabies.

In this article a review of the immunological response to S. scabiei, representing a confounding factor for the diagnosis of house dust mite (HDM) hypersensitivity is presented.

Clinical features and diagnosisAdult female mites dig tunnel-like burrows within the stratum granulosum of the epidermis and lay approximately 2–3 eggs daily. An infested subject hosts approximately 10–15 adult female mites on the entire body. The life cycle of scabies mites is 10–14 days.

The burrows are typically located on the interdigital spaces, the flexural surface of the wrists, elbows, axillae, umbilicus, belt line, nipples, buttocks, and penile shaft.1 They appear as short, wavy, threadlike scaling lines. The presence of erythematous papules or vesicles is attributed to a type IV hypersensitivity reaction to mite, eggs, and/or excrement antigens (Fig. 1), and the inflammatory response is characterised by the presence of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes.7

Clinical features that suggest the diagnosis of scabies include a polymorphic, papulovesicular, eczematous or pustular rash, intense itch (especially nocturnal and after taking hot showers), and associated secondary bacterial infections with S. aureus or nephritogenic Streptococcus. Diagnostic guidelines that have been proposed for scabies include a history of diffuse itching, lesions in at least two typical skin areas, and a household member with pruritus.8

The definitive diagnosis is established by the identification of the mite, its eggs or faeces by microscopic examination of scales obtained by skin scraping.9 Since this approach may not be satisfactory in some cases, other diagnostic methods with better sensitivity and specificity have been proposed, including Videodermatoscopy, Dermatoscopy, Reflectance Confocal Microscopy, and Optical Coherence Tomography.10

The differential diagnosis should take into account other pruritic skin conditions, including atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, papular urticaria, folliculitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, prurigo nodularis, impetigo, tinea, and bites from mosquitoes, fleas, bed bugs, and chiggers or other mites.

Crusted (Norwegian) scabiesThis variety of disease is a severe, highly contagious, form of scabies in which mites multiply into the millions, causing extensive skin hyperkeratotic crusting. The histopathologic study of the lesions shows a dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes with or without neutrophils and eosinophils, and a denser infiltration in the nodular lesions (Fig. 2).

Same patient as in Fig. 1 with crusted (Norwegian) scabies. Abundant nodules are present on penis and scrotum.

Crusted scabies can be treated with oral ivermectin 6mg once per week for three weeks, plus crotamiton topical ointment (benzyl benzoate 30%). Alternative treatment, if there is no response or adverse effects occur, is with topical 1% gamma-benzene hexachloride ointment applied from the neck down once a week.11

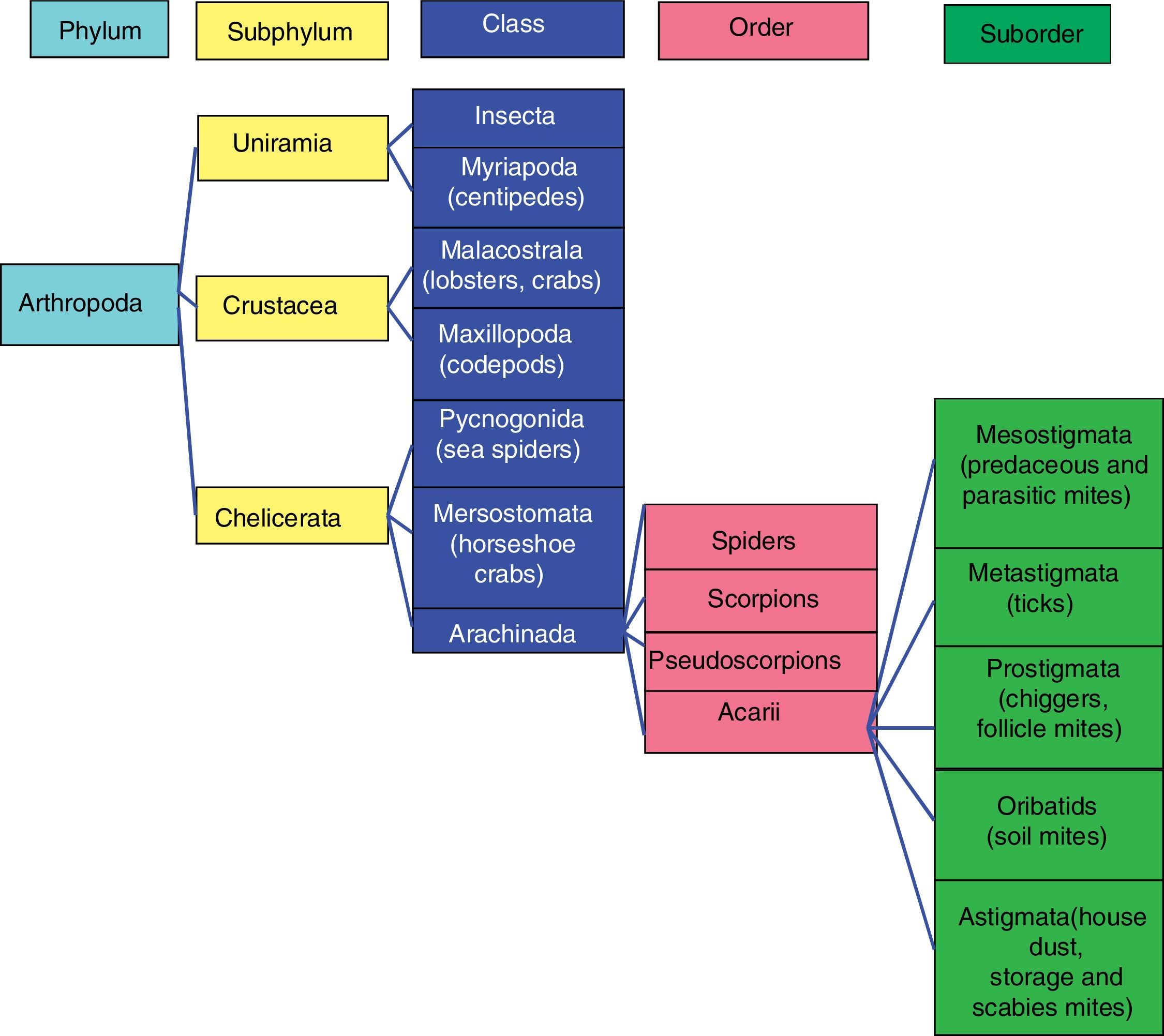

Immunological features of scabies and relevance in allergologyImmune response to scabiesScabies mites (SM) and HDM are phylogenetically-related arthropods. Since the HDM and the human SM have similar appearance and nutrition, it is not unlikely that they or their excretions have allergens in common (Fig. 3). S. scabiei mite produces a number of allergens homologous of HDM allergens, among them: Group 11 (paramyosin), group 14 (apolipoprotein), group 8 (glutathione S-transferase), group 3 (serine protease), and group 1 (cysteine protease).12

Importance of the immune response to scabies in allergologyScabies has two important repercussions in the routine practice of allergology:

- (1)

Itch is a frequent motive of consultation in the Allergy Clinics, since there are patients who think that the itchy rash they are suffering is due to skin allergy. Scabies has to be considered in the differential diagnosis of itchy rashes by allergists practicing in endemic areas, attending low-income or overcrowded populations, immunosuppressed subjects, and institutionalised patients. Additionally, the diagnosis of scabies should be entertained in areas of developed countries with increased crowding and immigration from third world locations.

- (2)

The allergenicity of S. scabiei leads to immune changes that can be confounders in the diagnosis of HDM allergy. In a high proportion of patients with scabies IgE antibodies to allergens from the HDM Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus can be demonstrated.13 It has been demonstrated that patients with scabies show serum IgE against recombinant S. scabiei cysteine and serine proteases and apolipoprotein, whereas naive (unexposed) subjects show minimal IgE reactivity, and positive immediate-type skin tests performed with HDM allergen extracts are observed in patients with past or current scabies infestation, which may be due to cross-reactive antibodies to Der p 4 and Der p 20.14,15

Sera from patients with scabies contain IgE against recombinant S. scabiei cysteine and serine proteases and apolipoprotein, whereas naive (unexposed) subjects show minimal IgE reactivity. Patients with crusted scabies have extremely high levels of total IgE in the serum.16,17 Polyclonal antibodies anti-S. scabiei cysteine protease bind to the mite gastrointestinal tract, which suggests that S. scabiei cysteine proteases play a role in skin digestion and mite burrowing.18

On the other hand, sera from patients with crusted scabies show strong IgE binding to up to 21 scabies mite proteins, while sera from patients with ordinary scabies show weaker binding to a maximum of six scabies mite proteins.19 Furthermore, recombinant glutathione S-transferase from S. scabiei reacts strongly with IgE and IgG4 in sera from crusted scabies patients.12

Greater serum IgE and IgG4 binding to mite apolipoprotein and eosinophilia were present in subjects with crusted scabies than in those with ordinary scabies, whereas peripheral blood mononuclear cells from subjects from both groups showed strong proliferative responses to scabies antigens, but the crusted scabies group showed a non-protective TH2 response characterised by an increased secretion of IL-5 and IL-13 and a decreased TH1 cytokine γ-interferon in response to the active cysteine protease.18

Scabies represents a major confounder in the diagnosis of HDM sensitisation because scabies-infested or exposed subjects have high-titre IgE binding to Der p 4 (amylase) and Der p 20 (arginine kinase) with the anti-Der p 4 persisting in previously exposed subjects. For group 4 allergens of mites (alpha amylases found in faeces) there is evidence for high cross-reactivity from present and past scabies infestations. Der p 20 exhibits high binding to IgE and IgG from the sera of people with active scabies.20 Also group 14 (large lipid transfer protein) of scabies binds to IgE at 10-fold higher levels for scabies infested but not HDM-allergic subjects.21

The use of component-resolved diagnosis (CRD) would clearly recognise the lack of Der p 1 and 2 antibodies and the high titres to Der p 4 and 20. This is likely to impact on the usefulness of HDM allergen extract testing in many countries where the prevalence of scabies infection is high.22 This will also be important in developing regions where changes in lifestyle are resulting in increased incidences of atopic diseases necessitating monitoring to predict health service needs. For example, in the United Kingdom the prevalence of scabies is 0.27% and therefore there will be a significant number of incorrect diagnoses in most regions.23

Finally, in tropical Australia cross-reactive anti-scabies antibodies contraindicate the use of HDM extracts for allergological diagnosis in many environments where allergic diseases might be expected to increase hand-in-hand with the increased sanitation of living conditions. IgE binding to Der p 4 and 20 and the absence of binding to Der p 1 and 2 can help to identify this.24

ConclusionsIn areas with high prevalence of S. scabiei infestation this skin disease has to be considered in allergy clinics, when evaluating patients with cutaneous itchy conditions. The presence of serum anti-S. scabies IgE antibodies in patients who previously developed scabies may lead to positive immediate-type skin tests to HDM allergenic extracts. This obstacle could be solved by utilising component-resolved diagnosis (molecular diagnosis).

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.