A high rate of cross-reactivity has been reported between the specific proteins of hen’s egg with proteins of various avian eggs by quantitative immunoelectrophoretic techniques. The aim of this study was to assess the clinical cross-reactivity of different birds’ eggs in children with hen’s egg allergy based on skin prick test results.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional study enrolled 52 infants with hen’s egg allergy and 52 healthy infants with no history of food allergy from October 2018 to April 2019. Skin prick tests were performed in both patient and control groups with fresh extract of white and yolk related to pigeon, duck, goose, turkey, quail, and partridge.

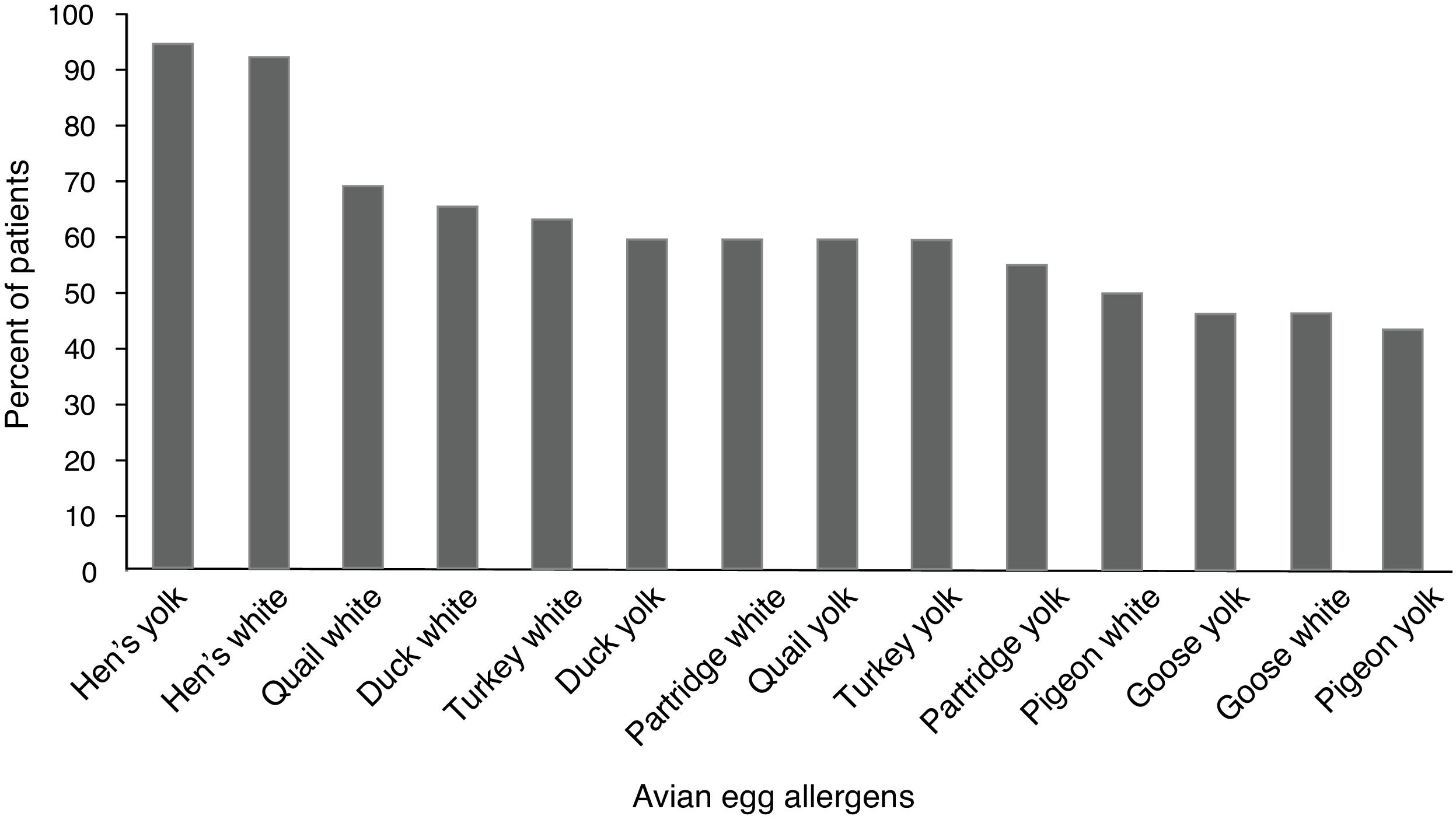

ResultsFifty (96.1%) children with hen’s egg allergy showed positive sensitization to at least one of the avian eggs. The most frequent positive skin tests were related to quail’s white (36 = 69.2%) followed by duck’s white (34 = 65.5%), and sensitization was the least frequent in pigeon’s yolk (23 = 44.2%). Skin tests of the control group were negative to all the tested extracts.

ConclusionBecause of fewer sensitizations to some avian eggs, further research should clarify starting oral immunotherapy with the yolk of goose and pigeon in children with hen’s egg allergy.

Hen’s egg allergy (HEA) is the main cause of IgE-mediated food allergy in 0.5–2.5 % of children younger than five years of age.1,2 IgE-mediated reactions to chicken’s egg often occur within several minutes to two hours after ingestion, and symptoms are related to the skin, gastrointestinal tract and rarely to respiratory system. The severity of symptoms varies from mild involvement in an organ to life-threatening anaphylaxis.3,4

Hen’s egg white proteins constitute ovomucoid, ovalbumin, ovotransferrin, lysozyme, and ovomucin. The major egg yolk protein is chicken serum albumin; however, the egg yolk displays less allergenicity than the white.5,6

Oral food challenges are the gold standard to establish food allergy definitively. The diagnosis of HEA is usually based on the detailed history of allergic reaction supported by in vivo skin prick test (SPT) or in vitro serum-specific IgE tests. SPT is a simple, safe, inexpensive and time-saving test for the evaluation of patients with food allergy. SPT was performed with standard commercial extracts or with fresh egg for egg allergy; a wheal size of 7 mm has a 95 percent positive predictive value (PPV) for children over two years of age and 5 mm has a 95 percent PPV for children two years or younger. Children with SPT results above these levels are presumed to be clinically reactive to eggs, and there is no need to perform oral food challenges.7–9

Allergens belong to a number of protein families. Cross-reactivity is defined as an immune-mediated phenomenon of an IgE antibody in the epitopes of the homologous protein of allergens. Cross-reactivity needs more than 70% similarity in protein sequence of allergens for inducing clinical allergic reactions.10 Several reports demonstrate the high rate of cross-reactivity in various foods: milk of cows, goats and sheep more than 90%; melons 90%; peanut, hazelnut and Brazil nut 59%; shellfish 75%; fruits such as apple, pear and peach 55%; and wheat, barley and rye 20%.11–13 Cross-reactive proteins are common within avian eggs. In vitro studies showed extensive cross-reactivity among the hen’s egg with egg white from turkey, duck, goose and seagull.14,15 Homologous proteins also influence hypersensitivity to chicken meat in individuals with allergy to avian eggs or feathers; it is called bird–egg syndrome with α-livetin (Gal d 5), as the most frequent cross-reacting protein.16

There are a few clinical implications on cross-reactivity of the avian eggs and meat in the literature. Knowledge about the occurrence of other types of avian egg allergy is essential in order to perform necessary eliminations in the diet of patients with hen’s egg allergy.

This study was designed to investigate the degree of cross-reactivity between avian eggs and also chicken meat using skin prick test among patients with documented hen’s egg allergy.

Methods and materialsThis cross-sectional study was performed on 52 infants and children with HEA who were referred to the allergy clinic at Aliasghar Hospital of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences from October 2018 to April 2019. Enrollment required a description of the immediate allergic symptoms after taking egg by the studied infants within minutes to two hours after ingestion at home, accompanied with the positive SPT result to the hen’s egg (white, yolk, or both). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.MED. REC.1397.334). The design and objectives of the study were explained to the infants’ parents, and written informed consent was obtained from the parents who were willing to participate in the study. Infants and children with negative SPT to the whole egg, no clinical allergy symptoms after ingestion of the hen’s egg and history of anaphylaxis to eggs were excluded in this study. Fifty-two children with no history of any food allergy were selected randomly from the same geographic area as the control group.

A questionnaire was filled out to obtain information about sex, age, paternal allergy, and having atopic dermatitis. For SPT, we used the standard commercial extracts of the hen’s egg, hen’s white and chicken (Greer, Lenoir, WA, USA). Sensitization to uncooked fresh extracts of white and yolk related to pigeon, duck, goose, turkey, quail and partridge was also evaluated, using skin prick-by-prick tests (SPPT) in which the culprits were pricked with a sterile lancet and then pricked into the skin with the same lancet. Histamine (10 mg/mL) and saline were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The results of the skin tests were examined after 15 min and considered positive when the wheal was >7 mm in diameter for children over two years of age and >5 mm for children aged two years or younger.

Statistical analysisDistributed data were presented as frequency (percentage). To examine the relationship between sensitization to yolk and white for avian eggs, Pearson Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

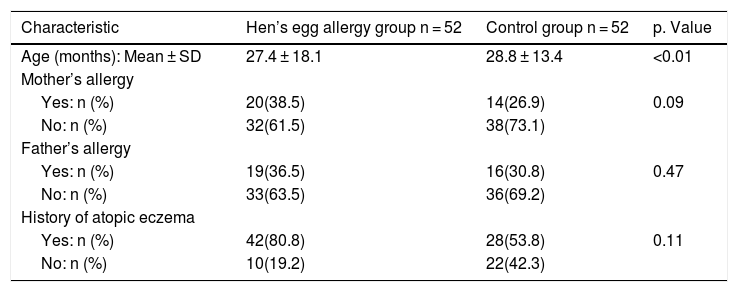

ResultsA total of 52 children (26 girls and 26 boys) with HEA ranging in age from 8 to 72 months and 52 controls (25 girls and 27 boys) without any food allergy ranging in age from 8 to 60 months were enrolled in the study. Characteristic data on infants with IgE mediated HEA in comparison to the control group are shown in Table 1; there was no significant difference in paternal allergy and history of atopic eczema.

Baseline demographic data of the two study groups.

| Characteristic | Hen’s egg allergy group n = 52 | Control group n = 52 | p. Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months): Mean ± SD | 27.4 ± 18.1 | 28.8 ± 13.4 | <0.01 |

| Mother’s allergy | |||

| Yes: n (%) | 20(38.5) | 14(26.9) | 0.09 |

| No: n (%) | 32(61.5) | 38(73.1) | |

| Father’s allergy | |||

| Yes: n (%) | 19(36.5) | 16(30.8) | 0.47 |

| No: n (%) | 33(63.5) | 36(69.2) | |

| History of atopic eczema | |||

| Yes: n (%) | 42(80.8) | 28(53.8) | 0.11 |

| No: n (%) | 10(19.2) | 22(42.3) |

For the hen’s white, the size of wheal and erythema were 9.3 ± 5.5 mm and 17.7 ± 9.5 mm, respectively. The size of wheal and erythema for the hen’s yolk were 7.1 ± 3.2 mm and 15.1 ± 7.1 mm, respectively. Fifty (96.1%) children with HEA showed positive sensitization to at least one of the avian eggs. None of the children in the control group had positive sensitization to various birds’ eggs by SPT.

Children with HEA were most commonly sensitized to quail’s white (36 = 59.2%) followed by duck’s white (34 = 65.5%), and sensitization was the least frequent to the pigeon’s yolk (23 = 44.2%). The percentile of positive SPT to various avian eggs in children with HEA is shown in Fig. 1. Co-allergy with chicken meat was found in (13 = 25%) of children with HEA. Positive SPT to white from all birds’ egg was more than their yolk; only for goose, this ratio was equal.

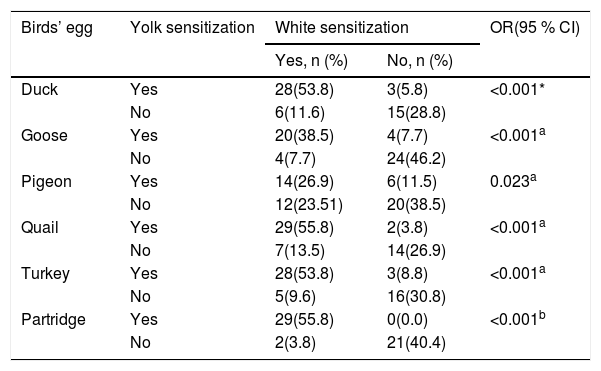

As shown for six birds’ egg in Table 2, there was a significant difference in sensitization between the white and yolk for each avian egg in patients with HEA.

Relationship between sensitization to the yolk and white for six birds’ eggs in 52 children with hen’s egg allergy.

| Birds’ egg | Yolk sensitization | White sensitization | OR(95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||

| Duck | Yes | 28(53.8) | 3(5.8) | <0.001* |

| No | 6(11.6) | 15(28.8) | ||

| Goose | Yes | 20(38.5) | 4(7.7) | <0.001a |

| No | 4(7.7) | 24(46.2) | ||

| Pigeon | Yes | 14(26.9) | 6(11.5) | 0.023a |

| No | 12(23.51) | 20(38.5) | ||

| Quail | Yes | 29(55.8) | 2(3.8) | <0.001a |

| No | 7(13.5) | 14(26.9) | ||

| Turkey | Yes | 28(53.8) | 3(8.8) | <0.001a |

| No | 5(9.6) | 16(30.8) | ||

| Partridge | Yes | 29(55.8) | 0(0.0) | <0.001b |

| No | 2(3.8) | 21(40.4) | ||

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing the results of SPT for various avian eggs among children with HEA. A positive SPT to at least one of the applied avian eggs was seen in 96.1% of our children with HEA. Children with HEA were most commonly sensitized to avian allergens in quail, duck, turkey, partridge, pigeon and goose by our SPT results, respectively. A new study emphasizes that all birds evolved from the same ancestor and that these birds are closely related.17

This study found that the most frequent sensitizations (about 70%) were seen in quail’s egg in children with HEA. Quail (Coturnix coturnix) and hen (Gallus domesticus) belong to the same family of Galliformes.18 Alessandri reported a case with HEA who presented with anaphylactic reaction after ingestion of quail’s egg; this could be due to cross-reaction between the specific proteins of the quail’s egg with proteins of the hen’s egg.19 There is one report from quail’s egg allergy without HEA in a 10-year-old girl; the author referred to the existence of dissimilar specific proteins in the quail’s egg.20

Sensitization to the duck’s egg was seen in 65% of our children; duck is classified as Anseriformes family and duck’s protein is almost similar to the hen’s protein.18 Langeland reported that allergenic activity to duck’s egg was 0.01 to 0.001 times more in individuals with HEA.14 Añíbarro reported an adult case with IgE-mediated food allergy to eggs from duck and goose without HEA; he suggested ovalbumin as the culprit protein.21

Turkey’s egg sensitization was found to be 63.5% among our patients; turkey belongs to the Galliformes family, like hen and quail.18 Langeland reported cross-reacting allergens in the egg white of turkey by quantitative immunoelectrophoretic techniques; moreover, he found proteins of egg whites from turkey cross-reacting with most of the allergens in the hen’s egg white.14

The partridge is in the Phasianidae family and sensitization to its egg was detected in about 60% of our children with HEA.18 Little information is available concerning the possible allergenic cross-reactivity between eggs from hen and partridge.

Lower egg bird sensitization in children with HEA was related to those to goose’s egg with 46% and pigeon’s egg yolk with 44% by our SPT results. Goose and pigeon constitute the avian family of Anseriformes and Columbiformes, respectively.18 Langeland reported that the occurrence of proteins cross-reacting with allergens in the hen’s egg white was fewer in goose compared to turkey and duck.14 Oral immunotherapy is promising as a tolerance induction protocol for food allergy; we suggest starting this approach for patients with HEA with the yolk of goose and pigeon and then changing them to the hen’s egg.

Chicken meat is a main dish for children; moreover, our results indicated that chicken meat elicits positive SPT in one-fourth of the children with HEA. Martínez Alonso JC presented angioedema due to chicken in the case of specific IgE antibodies to chicken meat and egg yolk.22 The major allergens in the hen’s yolk include serum albumins present in the chicken serum which are able to bind human IgE.23

Sensitization to most egg white was much more than the yolk in our patients with HEA. Given the existence of most of the allergenic hen’s egg proteins in the hen’s white, this might be applied to other avian birds.24

The presence of egg allergy has been proposed as a risk factor for atopic dermatitis; an investigation among children with atopic dermatitis showed 17.7% positive reactivity to the egg involving SPT.25 We observed no significant difference in the frequency of atopic eczema in children with HEA and the controls, while the majority of cases with HEA were suffering from atopic dermatitis in this study.

There was no significant difference in the frequency of paternal allergy in children with HEA and controls; this could possibly explain that the data was based only on the history of parents.

SPT remains useful for identifying the potential food allergens. Cooking and digestive enzymes of the gastrointestinal tract change the allergic properties of foods such as avian eggs; therefore, complimentary analysis by open food challenge is recommended for detecting allergy.26 The limitation of this study was impractical oral food challenge to various birds’ egg.

ConclusionThe results of the present study showed that 96% of children with HEA had positive sensitization to at least one of the avian eggs; this knowledge is essential in order to perform the necessary eliminations of avian eggs for children with HEA. The study also showed that the quail’s white and pigeon’s yolk were the most and least frequent types of sensitization in children with HEA, respectively. Further research on starting oral immunotherapy with the yolk of goose and pigeon in children with HEA would shed more light on this problem.

FundingThis work was supported by the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (a grant number: 1396-01-16484)

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran and also Center for Development of Clinical Research of Nemazee Hospital and Dr. Nasrin Shokrpour for editorial assistance.