The objective of the study was to examine the relationship between asthma and overweight–obesity in Spanish children and adolescents and to determine whether this relationship was affected by gender and atopy.

MethodsThe study involves 8607 Spanish children and adolescents from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood phase III. Unconditional logistic regression was used to obtain adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the association between asthma symptoms and overweight–obesity in the two groups. Afterwards, it was stratified by sex and rhinoconjunctivitis.

ResultsThe prevalence of overweight and obesity in 6–7-year-old children was 18.6% and 5.2% respectively and in 13–14 year-old teenagers was 11.4% and 1.1% respectively. Only the obese children, not the overweight children, of the 6–7 year old group had a higher risk of any asthma symptoms (wheezing ever: OR 1.68 [1.15–2.47], asthma ever: OR 2.29 [1.43–3.68], current asthma 2.56 [1.54–4.28], severe asthma 3.18 [1.50–6.73], exercise-induced asthma 2.71 [1.45–5.05]). The obese girls had an increased risk of suffering any asthma symptoms (wheezing ever: OR 1.73 [1.05–2.91], asthma ever: OR 3.12 [1.67–5.82], current asthma 3.20 [1.65–6.19], severe asthma 4.83[1.94–12.04], exercise-induced asthma 3.68 [1.67–8.08]). The obese children without rhinoconjunctivitis had a higher risk of asthma symptoms.

ConclusionsObesity and asthma symptoms were associated in 6–7 year-old children but not in 13–14 year-old teenagers. The association was stronger in non-atopic children and obese girls.

Overweight–obesity and asthma are two of the most significant chronic paediatric health problems worldwide.1,2 The worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents has increased substantially in children and adolescents in developed and in developing countries.2 The worldwide prevalence of childhood asthma increased between phase I and phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC study).1

Although findings are not always consistent, several studies suggest an association between asthma and overweight–obesity. A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis reported a significant association between high body weight and asthma in childhood.3 Furthermore, several prospective studies and systematic reviews suggest that asthma tends to be preceded by obesity and that obesity is associated with the persistence and intensity of asthma symptoms.4,5

Several studies have found that a relationship between asthma and overweight–obesity exists only in males,6,7 only in females8 or in both sexes.9 Thus, the relevance of gender in the relationship between asthma and obesity is unclear.

Additionally, there is some evidence that the link between asthma and excess of body weight is stronger for non-allergic asthma.10,11 In 1997 Braun-Fahrländer et al. concluded that the ISAAC core questions on rhinitis are sufficiently specific and consequently useful in excluding atopy.12 Since then, only one study has used the item of rhinoconjunctivitis from the ISAAC core questionnaire as a marker of atopy.9

The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between asthma symptoms and overweight–obesity. Secondly, it was to analyse the effect of gender and rhinoconjunctivitis, as a marker of atopy, in the relationship between asthma and overweight/obesity in two different age groups.

MethodsThe International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) is an international, multicentre, multiphase cross-sectional study. It was developed to investigate childhood asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and atopic eczema at the population level. The ISAAC study consists of three phases and the data used in this study correspond to the third phase of the ISAAC study conducted in the Pamplona metropolitan area.

According to the ISAAC protocol, parents or guardians of 6–7 year-old children and 13–14 year-old adolescents, who were attending schools in Pamplona metropolitan area, Spain, were asked to complete the written ISAAC phase III questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated into Spanish and Basque.

The first part of the questionnaire concerns symptoms of asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema. The second part asks about possible risk factors for the development of asthma and allergies. Our study analysed answers related to asthma symptoms, rhinoconjunctivitis, weight, height, and potential confounding factors, such as the presence of breastfeeding, maternal education or the presence of tobacco in the family environment.

For the purpose of this study, “wheezing ever” was defined as a positive answer to the question “Has your child/have you ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest at any time in the past?”

“Asthma ever” was defined as a positive answer to the question “Has your child/have you ever had asthma?”

“Current asthma” was defined as a positive response to the question “Has your child/have you had wheezing or whistling in the chest during the last 12 months?”

“Current severe asthma” (CSA) was defined by fulfilling one or more criteria:

- •

Four or more asthma attacks in the past 12 months, or

- •

Sleep was disturbed ≥1 night/week in the last 12 months, or

- •

Wheezing limiting speech to one or two words at a time between breaths in the last 12 months.

“Exercise-induced asthma” was defined as a positive answer to the question “In the last 12 months, has your child's chest sounded wheezy during or after exercise?/have you had wheezing or whistling in the chest during or after exercise?”

Rhinoconjunctivitis was defined as a positive response to the following two questions;

- -

“In the past 12 months, has your child/have you had a problem with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose when he/she did not have a cold or the flu?” And

- -

“If yes, has this nose problem been accompanied by itchy watery eyes?”.13,14

Self-reported height and weight or those measurements reported by the parents were used to calculate body mass index (BMI) in kg/m2. Obesity, overweight and normal weight were defined according to the BMI cut-off points set by Cole et al.15 for each group by age and sex.

Non-conditional multiple logistic regression was used to obtain adjusted prevalence odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the association between obesity–overweight and asthma symptoms in both groups, taking as reference the normal weight group. Secondly, stratification was done by rhinoconjunctivitis and by gender.

The statistical analysis was performed with the software SPSS 20.0.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the department of Health Sciences at the Public University of Navarra, Spain.

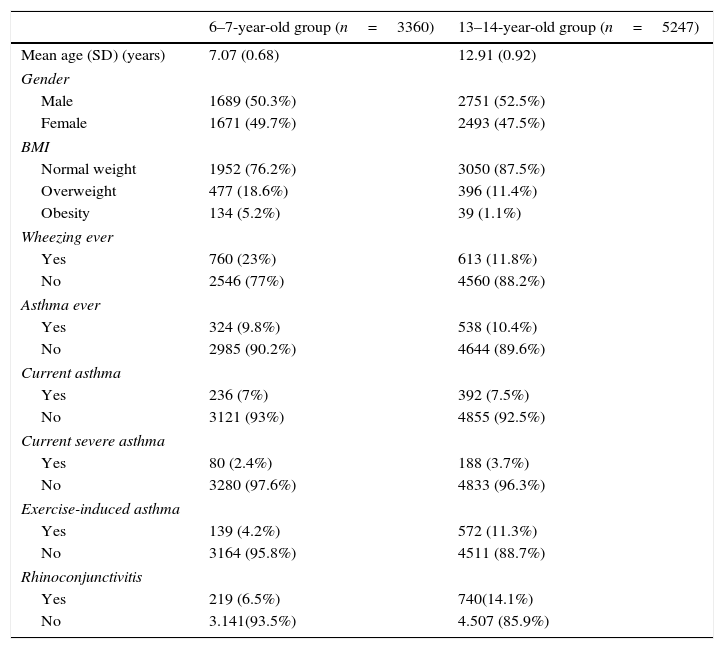

ResultsThere were 3360 children in the 6–7 year-old group and 5247 teenagers in the 13–14 year-old group. The response rate was 78.7% for the 6–7 year-old group and the 82.6% for the 13–14 year-old group. Those with no available data on BMI (n=797 6–7 year-old; n=1762 13–14 year-old) were not used in the analysis for the association between obesity–overweight and asthma symptoms in both groups and neither were used in the stratification by rhinoconjunctivitis and by gender.

The prevalence of obesity and overweight in the children group was 5.2% and 18.6% respectively. In the teenager group, 1.1% were obese and 11.4% were overweight (Table 1).

Characteristics of the subjects and prevalence of asthma symptoms.

| 6–7-year-old group (n=3360) | 13–14-year-old group (n=5247) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) (years) | 7.07 (0.68) | 12.91 (0.92) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1689 (50.3%) | 2751 (52.5%) |

| Female | 1671 (49.7%) | 2493 (47.5%) |

| BMI | ||

| Normal weight | 1952 (76.2%) | 3050 (87.5%) |

| Overweight | 477 (18.6%) | 396 (11.4%) |

| Obesity | 134 (5.2%) | 39 (1.1%) |

| Wheezing ever | ||

| Yes | 760 (23%) | 613 (11.8%) |

| No | 2546 (77%) | 4560 (88.2%) |

| Asthma ever | ||

| Yes | 324 (9.8%) | 538 (10.4%) |

| No | 2985 (90.2%) | 4644 (89.6%) |

| Current asthma | ||

| Yes | 236 (7%) | 392 (7.5%) |

| No | 3121 (93%) | 4855 (92.5%) |

| Current severe asthma | ||

| Yes | 80 (2.4%) | 188 (3.7%) |

| No | 3280 (97.6%) | 4833 (96.3%) |

| Exercise-induced asthma | ||

| Yes | 139 (4.2%) | 572 (11.3%) |

| No | 3164 (95.8%) | 4511 (88.7%) |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis | ||

| Yes | 219 (6.5%) | 740(14.1%) |

| No | 3.141(93.5%) | 4.507 (85.9%) |

Prevalence of “current asthma” was similar in children and teenager groups; 7% and 7.5%, respectively. “Current severe asthma” was more frequently reported in the teenager group (3.7% vs. 2.4%), as was “exercise-induced asthma” (11.3% vs. 4.2%) and rhinoconjunctivitis (14.1% vs. 6.5%) (Table 1).

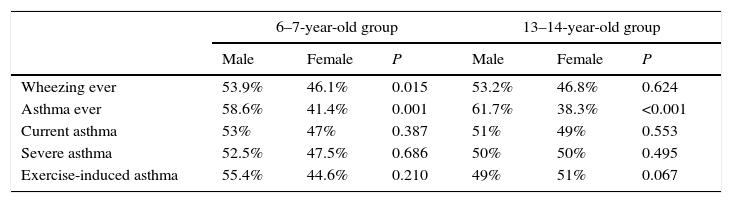

The prevalence of asthma symptoms was similar in males and females. However, in both age groups, “asthma ever” was more prevalent in boys than girls (Table 2).

Prevalence of asthma symptoms by age group and sex.

| 6–7-year-old group | 13–14-year-old group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | P | Male | Female | P | |

| Wheezing ever | 53.9% | 46.1% | 0.015 | 53.2% | 46.8% | 0.624 |

| Asthma ever | 58.6% | 41.4% | 0.001 | 61.7% | 38.3% | <0.001 |

| Current asthma | 53% | 47% | 0.387 | 51% | 49% | 0.553 |

| Severe asthma | 52.5% | 47.5% | 0.686 | 50% | 50% | 0.495 |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 55.4% | 44.6% | 0.210 | 49% | 51% | 0.067 |

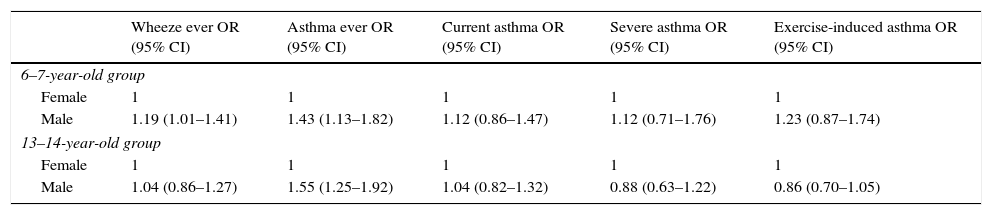

The adjusted OR shows that, at both age groups, males have more risk of having “asthma ever” (Table 3).

Association between asthma symptoms and gender, adjusted by age, breast feeding, mother's education and parental smoking.

| Wheeze ever OR (95% CI) | Asthma ever OR (95% CI) | Current asthma OR (95% CI) | Severe asthma OR (95% CI) | Exercise-induced asthma OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6–7-year-old group | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.19 (1.01–1.41) | 1.43 (1.13–1.82) | 1.12 (0.86–1.47) | 1.12 (0.71–1.76) | 1.23 (0.87–1.74) |

| 13–14-year-old group | |||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.04 (0.86–1.27) | 1.55 (1.25–1.92) | 1.04 (0.82–1.32) | 0.88 (0.63–1.22) | 0.86 (0.70–1.05) |

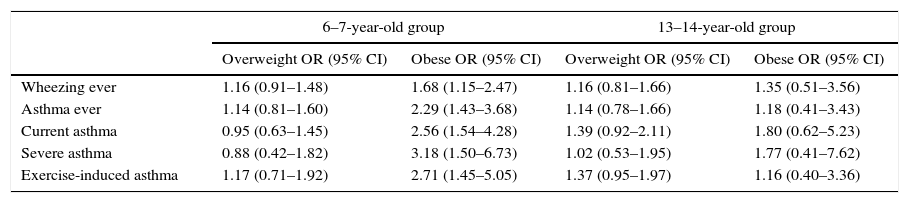

For the 6–7 year-old group, all asthma symptoms (“wheezing ever”, “asthma ever”, “current asthma”, “severe asthma” and “exercise-induced asthma”) were associated with obesity. There was no association between asthma symptoms and obesity in the 13–14 year-old group. Neither age group presented a significant association between asthma symptoms and overweight (Table 4).

Association between overweight and obesity and asthma symptoms at 6–7 year olds and 13–14 year olds. Data are OR (95% CI) and are adjusted for age, sex, breast feeding, mother's education and parental smoking.a

| 6–7-year-old group | 13–14-year-old group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | |

| Wheezing ever | 1.16 (0.91–1.48) | 1.68 (1.15–2.47) | 1.16 (0.81–1.66) | 1.35 (0.51–3.56) |

| Asthma ever | 1.14 (0.81–1.60) | 2.29 (1.43–3.68) | 1.14 (0.78–1.66) | 1.18 (0.41–3.43) |

| Current asthma | 0.95 (0.63–1.45) | 2.56 (1.54–4.28) | 1.39 (0.92–2.11) | 1.80 (0.62–5.23) |

| Severe asthma | 0.88 (0.42–1.82) | 3.18 (1.50–6.73) | 1.02 (0.53–1.95) | 1.77 (0.41–7.62) |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 1.17 (0.71–1.92) | 2.71 (1.45–5.05) | 1.37 (0.95–1.97) | 1.16 (0.40–3.36) |

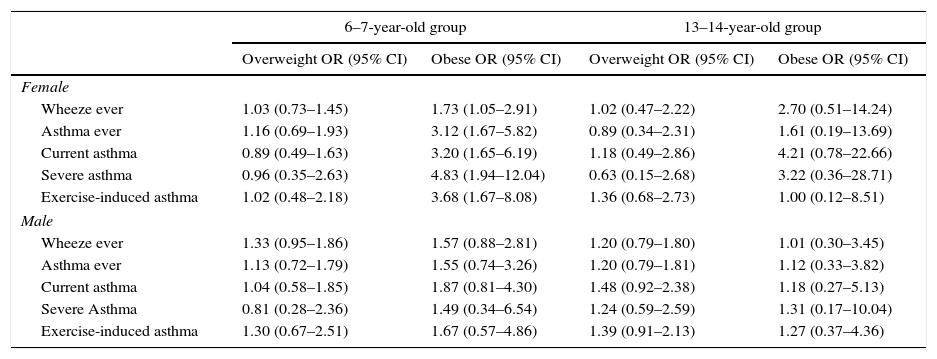

The association between obesity and asthma symptoms was modified by gender. For obese, 6–7 year-old girls, the OR for “severe asthma” was 4.83 and the OR for “exercise-induced asthma” was 3.68. Such strong associations were not seen in teenage girls and boys in either age group (Table 5).

Association between overweight and obesity and symptoms of asthma, stratified by gender. Data are OR (95% CI) and are adjusted for age, breast feeding, mother education and parental smoking.a

| 6–7-year-old group | 13–14-year-old group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | |

| Female | ||||

| Wheeze ever | 1.03 (0.73–1.45) | 1.73 (1.05–2.91) | 1.02 (0.47–2.22) | 2.70 (0.51–14.24) |

| Asthma ever | 1.16 (0.69–1.93) | 3.12 (1.67–5.82) | 0.89 (0.34–2.31) | 1.61 (0.19–13.69) |

| Current asthma | 0.89 (0.49–1.63) | 3.20 (1.65–6.19) | 1.18 (0.49–2.86) | 4.21 (0.78–22.66) |

| Severe asthma | 0.96 (0.35–2.63) | 4.83 (1.94–12.04) | 0.63 (0.15–2.68) | 3.22 (0.36–28.71) |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 1.02 (0.48–2.18) | 3.68 (1.67–8.08) | 1.36 (0.68–2.73) | 1.00 (0.12–8.51) |

| Male | ||||

| Wheeze ever | 1.33 (0.95–1.86) | 1.57 (0.88–2.81) | 1.20 (0.79–1.80) | 1.01 (0.30–3.45) |

| Asthma ever | 1.13 (0.72–1.79) | 1.55 (0.74–3.26) | 1.20 (0.79–1.81) | 1.12 (0.33–3.82) |

| Current asthma | 1.04 (0.58–1.85) | 1.87 (0.81–4.30) | 1.48 (0.92–2.38) | 1.18 (0.27–5.13) |

| Severe Asthma | 0.81 (0.28–2.36) | 1.49 (0.34–6.54) | 1.24 (0.59–2.59) | 1.31 (0.17–10.04) |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 1.30 (0.67–2.51) | 1.67 (0.57–4.86) | 1.39 (0.91–2.13) | 1.27 (0.37–4.36) |

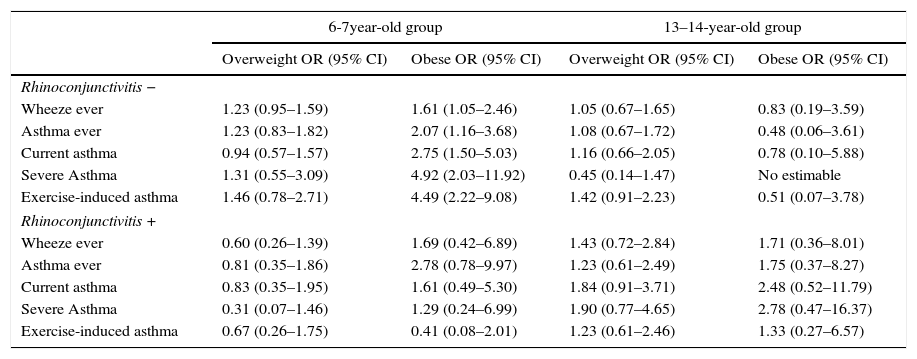

Obese 6–7-year-old children without rhinoconjunctivitis, have a higher risk of suffering any asthma symptoms. In obese 6–7-year-old children without rhinoconjunctivitis, the OR for “exercise-induced asthma” was 4.9 and that for “severe asthma” was 4.5. Overweight in the same age group, with or without rhinoconjunctivitis, was not associated with symptoms of asthma. In the 13–14-year-old group, there was no association between overweight or obesity and asthma symptoms when we stratified by rhinoconjunctivitis (Table 6).

Association between overweight, obesity, symptoms of asthma and the coexistence of rhinoconjunctivitis, adjusted for age, sex, breast feeding, mother's education and parental smoking.a

| 6-7year-old group | 13–14-year-old group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | Overweight OR (95% CI) | Obese OR (95% CI) | |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis − | ||||

| Wheeze ever | 1.23 (0.95–1.59) | 1.61 (1.05–2.46) | 1.05 (0.67–1.65) | 0.83 (0.19–3.59) |

| Asthma ever | 1.23 (0.83–1.82) | 2.07 (1.16–3.68) | 1.08 (0.67–1.72) | 0.48 (0.06–3.61) |

| Current asthma | 0.94 (0.57–1.57) | 2.75 (1.50–5.03) | 1.16 (0.66–2.05) | 0.78 (0.10–5.88) |

| Severe Asthma | 1.31 (0.55–3.09) | 4.92 (2.03–11.92) | 0.45 (0.14–1.47) | No estimable |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 1.46 (0.78–2.71) | 4.49 (2.22–9.08) | 1.42 (0.91–2.23) | 0.51 (0.07–3.78) |

| Rhinoconjunctivitis + | ||||

| Wheeze ever | 0.60 (0.26–1.39) | 1.69 (0.42–6.89) | 1.43 (0.72–2.84) | 1.71 (0.36–8.01) |

| Asthma ever | 0.81 (0.35–1.86) | 2.78 (0.78–9.97) | 1.23 (0.61–2.49) | 1.75 (0.37–8.27) |

| Current asthma | 0.83 (0.35–1.95) | 1.61 (0.49–5.30) | 1.84 (0.91–3.71) | 2.48 (0.52–11.79) |

| Severe Asthma | 0.31 (0.07–1.46) | 1.29 (0.24–6.99) | 1.90 (0.77–4.65) | 2.78 (0.47–16.37) |

| Exercise-induced asthma | 0.67 (0.26–1.75) | 0.41 (0.08–2.01) | 1.23 (0.61–2.46) | 1.33 (0.27–6.57) |

Obesity and asthma are two of the chronic paediatric health problems worldwide. Our study has found a relationship between these diseases only in the 6–7-year-old children, not in the adolescent group. This association was stronger in non-atopic children than in atopic children and stronger in obese girls than in obese boys.

The most recent study of the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Spain found that 35.2% of children aged between 6 and 10 years had excess body weight, according to the Cole standards.16 In our study, excess body weight affected 23.8% of 6–7 year olds and 12.5% of 13–14 year olds. In a methodologically comparable study also conducted in Navarra, Spain, the prevalence of excess body weight was 21.7% in the 6-year-old children and 22.5% in the adolescents.17

Regarding cross-national studies that applied the Cole et al. standards, and that have been published in the last decade, our study finds a similar prevalence of obesity and overweight in children but a lower prevalence of obesity and overweight in teenagers. This lower prevalence in adolescents in our study may result from the fact that weight and height data were self-reported.16

The metropolitan area of Pamplona had a lower prevalence of current asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis in both age groups compared with the worldwide prevalence according to the ISAAC study. According to phase III of the ISAAC study the prevalence of “current asthma” and rhinoconjunctivitis in the 6–7-year-old group was 11.7% and 8.5% respectively. In the 13–14-year-old group the prevalence of “current asthma” and rhinoconjunctivitis was 14.1% and 14.6%, respectively.18 Spain had a lower prevalence of asthma in both age groups and a lower prevalence of rhinoconjunctivitis in the younger age group. The prevalence for “current asthma” and rhinoconjunctivitis in the 6–7-year-old group was 9.9%19 and 8.2%20 respectively. In the older age group, the prevalence of “current asthma” and rhinoconjunctivitis was 10.6%19 and 15.5%,20 respectively. Despite the low prevalence of asthma symptoms in the metropolitan area of Pamplona we have been able to observe an association between asthma and obesity in the 6–7-year-old group.

The epidemiological data on adults suggest that the phenotype “obese asthmatic” exists as a distinct clinical phenotype.5 The obese asthmatic adult has a non-eosinophilic inflammation with a predominance of neutrophils. The asthmatic obese phenotype is more common in females. No relationship has been found between obesity and atopy for obese asthmatic adults.21,22 The phenotype presents systemic inflammation with a reduced response to corticosteroid treatment and more severe asthma.22 However, the clinical presentation of the obese asthma in children has not been thoroughly evaluated.3,22

Asthma is characterised by a Th2-mediated inflammation with an elevation of interleukins (IL): IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13.23 There is an increase in the number of T cells and mast cells, and eosinophils are elevated in the airway.24,25 In contrast, obesity is characterised by low-grade chronic inflammation with an elevation of leptin,21,23 which triggers the release of various cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-6 and IL-12,22 and enhances the differentiation of monocytes and neutrophils. Additionally, leptin activates the T helper 1 (Th1)-cell differentiation and inhibits T helper 2 (Th2)-cell differentiation.23

Obese children do not have the typical asthmatic allergic response seen in adults. An explanation proposed for this difference is that in children, obesity associated asthma involves Th1 rather than Th2 polarisation.23 This immune pattern and the asthmatic obese phenotype can explain the results obtained in this and other studies in obese asthmatic children.11,13

In our study, obese children were found to have higher risk of suffering “exercise-induced asthma” and an increased risk of “severe asthma”. In children, obesity is associated with more asthma exacerbations, higher emergency department attendance, worse asthma control, poor response to therapy and greater severity of symptoms.22,26,27 Some degree of these associations can, however be explained by an overestimation of clinical symptoms resulting from a heightened awareness of non-specific symptoms, such as breathlessness.21

Another area of controversy in the relationship between asthma and obesity is whether the association is affected by gender. A recent meta-analysis described a relationship between obesity and asthma in boys but not girls.7 A separate systematic review, however, determined that the role of gender was unclear.4 In our study, we found that obese girls have a higher risk of asthmatic symptoms. The risk of having severe asthma increases up to five times and the risk of having exercise-induced asthma increases up to four times in the obese girls compared with the normal weight girls.

In our group of 13–14 year olds, despite the prevalence of “exercise-induced asthma” and “severe asthma” being higher in the obese than the non-obese, there was no association between female gender and obesity–asthma.

Castro-Rodríguez et al.8 observed that girls who developed overweight between the ages of 6 and 11 years, were more likely to show new symptoms of asthma between ages of 11 or 13 years; this tendency was not observed males. The same study also found that the association between obesity and asthma was stronger in girls who started puberty before 11 years of aged than in girls with later pubertal development. Similarly, in 2005, Varraso et al.28 reported that the relationship between BMI and severity of asthma was stronger in girls with early menarche.

In this study, pubertal stage could not be evaluated so this could be one of the reasons of not having found an association between obesity–asthma and gender in the 13–14-year-old group.

Our adolescent group, had a low prevalence of obesity and overweight in comparison to data published by Dura et al.29 This discrepancy may be due to underestimation of weight and overestimation of height by adolescents who self-reported these values, another factor could be a digit preference.30 The weight and height data were reported by parents, in the group of children of 6–7 years are reliable,31 however, the values supplied by the adolescents themselves can be subject a reporting bias. This bias can explain, in part, why we could not find a relationship between obesity and asthma in the teenager group.

Another limitation of our study was the use of rhinoconjunctivitis as a marker of atopy, more specific markers, such as IgE, are available.32 Furthermore, it would be interesting to evaluate the effect of gender after adjusting by rhinoconjunctivitis, but the number of obese children in our study was insufficient to permit this statistical procedure.

The increasing prevalences of obesity and asthma in children and adolescents make it necessary to continue studying the obese asthmatic phenotype in these groups. Further studies are needed to understand how obesity and the metabolic abnormalities associated with it promote the development of asthma. Another area in need of research concerns how childhood asthma treatment is affected by overweight–obesity. Finally, because an obese child often becomes an obese adult, therefore, continued research into the clinical management of the obese child of today will help to improve health in the adult of the future.

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This study was founded by a research help from de Health Department from Navarra Government and the ISAAC Study was approved by The Regional Ethics Committee of Asturias.