Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of advanced chronic liver disease in Latin-America, although data on prevalence is limited. Public health policies aimed at reducing the alarming prevalence of alcohol use disorder in Latin-America should be implemented. ALD comprises a clinical-pathological spectrum that ranges from steatosis, steatohepatitis to advanced forms such as alcoholic hepatitis (AH), cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Besides genetic factors, the amount of alcohol consumption is the most important risk factor for the development of ALD. Continuous consumption of more than 3 standard drinks per day in men and more than 2 drinks per day in women increases the risk of developing liver disease. The pathogenesis of ALD is only partially understood and recent translational studies have identified novel therapeutic targets. Early forms of ALD are often missed and most clinical attention is focused on AH, which is defined as an abrupt onset of jaundice and liver-related complications. In patients with potential confounding factors, a transjugular biopsy is recommended. The standard therapy for AH (i.e. prednisolone) has not evolved in the last decades yet promising new therapies (i.e. G-CSF, N-acetylcysteine) have been recently proposed. In both patients with early and severe ALD, prolonged abstinence is the most efficient therapeutic measure to decrease long-term morbidity and mortality. A multidisciplinary team including alcohol addiction specialists is recommended to manage patients with ALD. Liver transplantation should be considered in the management of patients with end-stage ALD that do not recover despite abstinence. In selected cases, increasing number of centers are proposing early transplantation for patients with severe AH not responding to medical therapy.

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a major cause of chronic liver disease in Latin-America [1]. Although data on prevalence in Latin-America is scarce, alcohol is reported to have been the main cause of cirrhosis in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Peru [2–4]. According to the WHO Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health of 2018, individuals above 15 years of age drink 8 liters of pure alcohol per year in the WHO Region of the Americas and over 6.4l globally [5]. Researchers have largely neglected this disease, and as a result the treatment has remained unaltered for many years [6]. Recently, there has been a renewed interest in understanding the pathophysiology and natural history of ALD, which has yielded the discovery of novel targets. The current concepts and recent advances in ALD have been summarized in clinical practice guidelines (CPG) from important international scientific societies [7–9].

The current CPG are the result of the effort of the Latin-American Special Interest Group for the Study of Alcohol-related Liver Disease (ALEH-GLEHA), under the sponsorship of the Latin-American Association for the Study of the Liver (ALEH) (http://alehlatam.org/). The aims of these CPG are to provide physicians with evidence-based clinical recommendations, tailored to Latin-American patients, identifying areas of improvement, collaboration, and research. The evidence and the expert panel recommendations were graded according to the Grading Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [10].

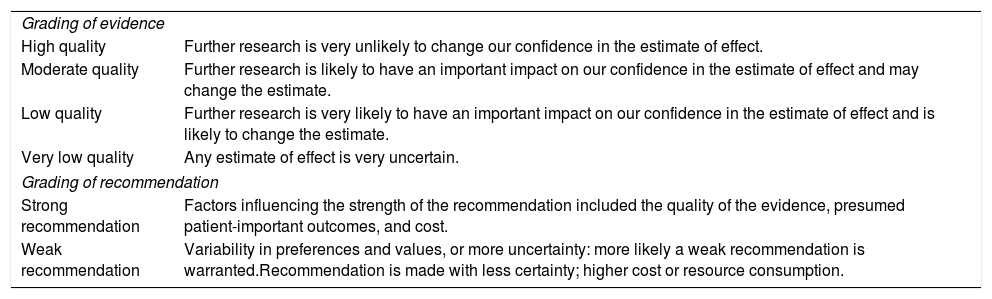

The strength of recommendations reflects the quality of underlying evidence. The quality of the evidence in these CPGs has been classified into one of four levels: high, moderate, low or very low, considering the confidence in the effect estimate based on current literature. The GRADE system offers two grades of recommendation: strong or weak (Table 1). These CPG thus consider the quality of evidence: the higher the quality of evidence, the more likely a strong recommendation is warranted; the greater the variability in values and preferences, or the greater the uncertainty, the more likely a weaker recommendation is warranted.

Grading of evidence and recommendations.

| Grading of evidence | |

| High quality | Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. |

| Moderate quality | Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. |

| Low quality | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. |

| Very low quality | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain. |

| Grading of recommendation | |

| Strong recommendation | Factors influencing the strength of the recommendation included the quality of the evidence, presumed patient-important outcomes, and cost. |

| Weak recommendation | Variability in preferences and values, or more uncertainty: more likely a weak recommendation is warranted.Recommendation is made with less certainty; higher cost or resource consumption. |

Alcohol-related liver disease comprises of a clinical-pathological spectrum, which ranges from steatosis, alcohol-related steatohepatitis (ASH) and progressive fibrosis. Patients with advanced forms, which are associated with liver failure and complications of portal hypertension, include alcoholic hepatitis (AH), alcohol-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [11]. Most heavy drinkers (almost 90%) develop steatosis, which is the earliest histopathological liver manifestation of alcohol ingestion. Steatosis can develop as soon as 3–7 days after heavy alcohol consumption. Steatosis is mostly asymptomatic and may be associated with mild elevations of gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT). It is histologically characterized by macrovesicular fat accumulation, typically located in centrilobular areas. Isolated steatosis should not be considered a benign condition since it can evolve to more severe forms. Continuous and excessive alcohol drinking may lead, in 10–35%, to the development of ASH, which is characterized by steatosis, hepatocellular damage (i.e. ballooning, Mallory-Denk bodies – MDB), inflammatory infiltrates – mainly neutrophils–, and different stages of fibrosis that present with a pericellular pattern [11]. Approximately 20–40% of patients with ASH will develop progressive fibrosis, of which 8–20% will develop cirrhosis. Some patients may present AH, which usually occurs in the context of ASH with advanced fibrosis or in patients with established cirrhosis. Currently, AH is considered a form of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF), which is characterized by hepatocellular damage, severe fibrosis (mainly cirrhosis), an intense systemic inflammatory response, multiorgan failure and high short-term mortality (18–50% at 3 months) [12,13]. Unfortunately, most patients with ALD are diagnosed at an advanced stage, when they develop jaundice or other complications of cirrhosis [14]. An Argentinean study reported a 32.2% incidence of AH by clinical plus histology criteria in patients with ALD [15], but its incidence in Latin-America is unknown. In the region, the aforementioned study from Argentina reported a short-term mortality of 40%. Studies from Mexico show a mortality of 63% and 89% at 30 and 90 days, respectively [15,16]. This highlights the importance of characterizing this disease in Latin-America, since mortality seems to be higher than in other regions. Latin-Americans may also have higher percentages of cirrhosis in patients who are hospitalized with AH [16]. A large observational study to characterize AH is this region in underway.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 1.

ALD is the main cause of cirrhosis in Latin-America. Excessive alcohol consumption should be actively sought as a cause of cirrhosis (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 1.

Natural history studies assessing characteristics of the disease in the region, ideally including multiple centers and countries.

- 2.

Studies evaluating the natural history of the disease, with a special emphasis on early stages of ALD and AH, due to a higher mortality observed in Latin-American populations.

The amount of alcohol intake is the most important risk factor for developing ALD [17]. However, extensive individual variability exists as only 10–20% of heavy alcohol drinkers develop cirrhosis. Other disease modifiers that influence the development and progression of ALD include alcohol-related factors (i.e. pattern of drinking, predominant type of alcoholic beverage consumed), environmental factors (presence of undernutrition/obesity, co-existence of chronic hepatitis B or C, and cigarette smoking), and genetic/epigenetic factors.

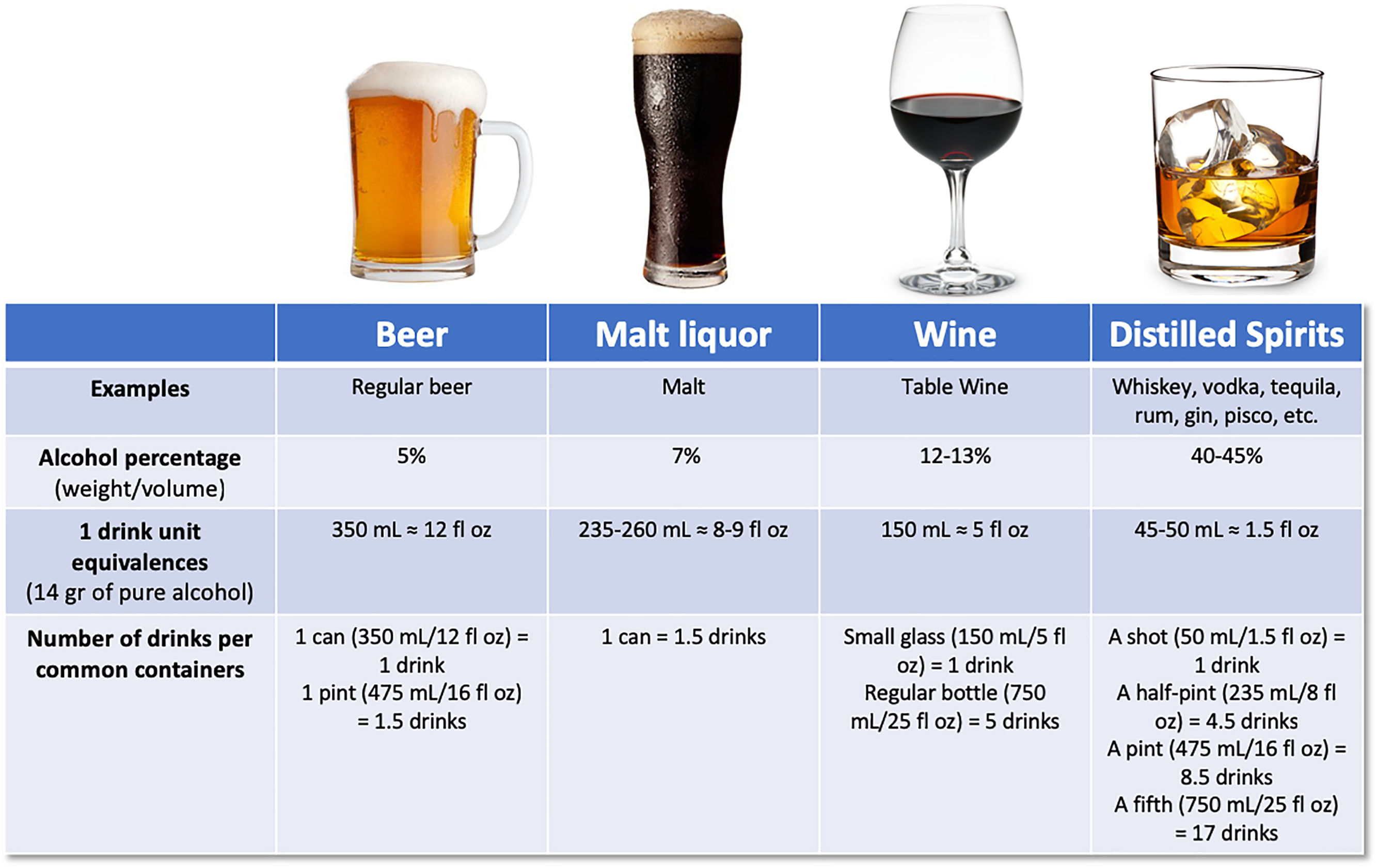

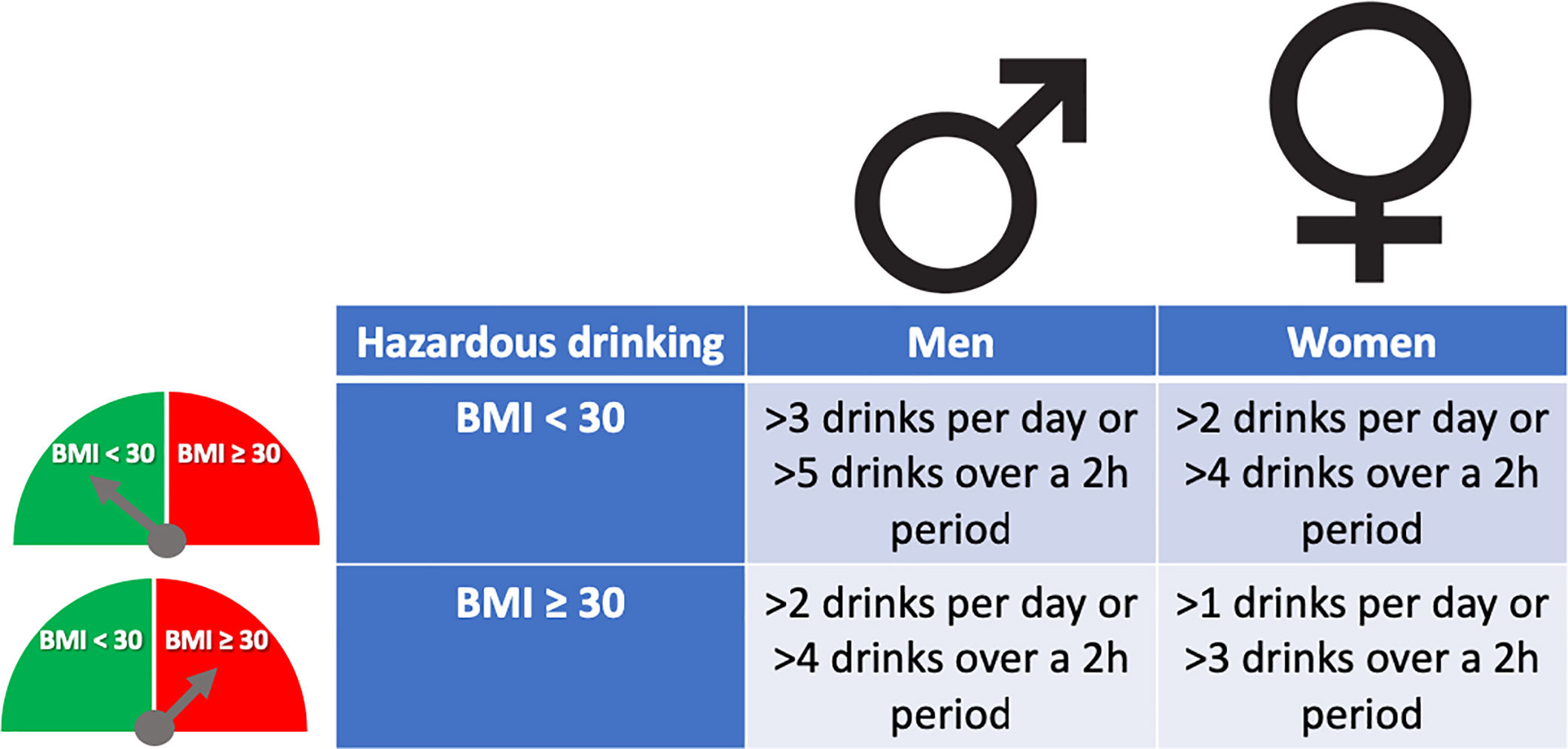

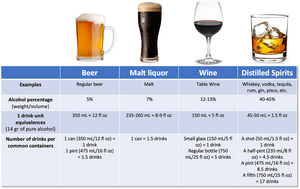

There has been large controversy in the definition of a standard drink, regarding the grams of alcohol, varying from 8 to 16g. According to the Dietary guidelines for Americans, one standard drink of “pure” alcohol is defined as 14g [18], which is equivalent to approximately 350mL of beer (5% weight/volume), 150mL of wine (12–13% weight/volume), or 45–50mL of liquor (40–45% weight/volume) [19] (Fig. 1). Alcohol-use disorder (AUD) is defined as consumption of more than 3 standard drinks per day in men, and more than 2 drinks per day in women, or binge drinking (defined as more than 5 standard drinks in men and more than 4 in women over a 2h period) [9]. It implies a greater risk of developing health problems associated with alcohol.

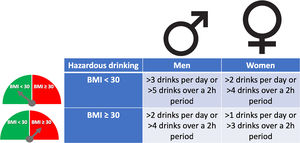

The pattern of drinking, especially heavy episodic drinking/binge drinking, is another factor that has been proposed to favor ALD. However, a clear role in humans has not been proven, and new studies are required [20]. The role of type of alcohol drink consumed (i.e. liquor, beer or wine) on the development of severe forms of ALD is not well known [21]. Women are more sensitive to alcohol-mediated hepatotoxicity. They are prone to develop severe ALD at lower doses and with shorter duration of alcohol consumption than men [22]. This could be explained by their higher body fat composition and lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity [23]. Overweight and obesity have also been associated with increased ALD risk. The combination of both, heavy alcohol drinking and obesity/overweight (especially BMI>30), synergistically induce liver disease [24,25]. For that reason, it is recommended to reduce cut-off levels of hazardous drinking in obese subjects (Fig. 2). Large epidemiological studies have found that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption, even in obese patients, may reduce the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [26]. Furthermore, it has been observed that in patients with NAFLD, the severity of inflammation and fibrosis could decrease with low alcohol consumption [27,28]. A large recent study, however, showed that even one single drink per day increases all-cause mortality, probably related to cancer [29]. In the clinical setting, patients with obesity-related liver disease are recommended to limit the amount of alcohol consumption. In addition, we should consider other risk factors, such as type of drink and genetic factors [30]. The presence of protein calorie malnutrition has an important role in determining the outcome of patients with ALD. Mortality increases in direct proportion to the extent of malnutrition, approaching 80% in patients with severe malnutrition (i.e., <50% of normal body weight) [31].

Excessive alcohol consumption has also shown to increase the risk of advanced liver disease and HCC in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection [32,33]. Additionally, alcohol has a synergistic hepatotoxic effect with NAFLD, iron overload and other metabolic disorders [11]. Interestingly, coffee seems to have a protective effect against liver injury in people who drink alcohol, however, current available data is controversial [34].

Genetic factors are involved in the onset, progression, and clinical outcome of ALD. Epidemiological studies conducted among family members and between twins strongly support a genetic component [35–37]. Moreover, ethnicity influences the susceptibility to ALD, and Latin-America is very heterogeneous. Studies conducted in Mexico, have identified genetic polymorphisms among Amerindian populations that would increase the predisposition and severity of ALD [38,39]. Similarly, studies conducted in United States of America have shown that Individuals with Hispanic ancestry have a higher incidence and a more aggressive pattern of liver disease than individuals of other ethnic groups [40,41]. In recent years, the polymorphisms of the gene coding for Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) have generated great interest, which would play a key role in the development of alcohol-related cirrhosis. The PNPLA3 I148M genetic variant, which functionally involves the loss of protein function with a consequent increase in intrahepatic fat and progression of liver disease, was found primarily in patients with NAFLD [39]. Studies conducted in the region, in South America and also in Mexico, have shown that this polymorphism is significantly more frequent in individuals with Native American ancestry and it is a risk factor for the development of advanced liver disease [42–44]. Subsequently, it has been demonstrated that individuals carrying this polymorphism constitute a genetic subpopulation with an increased risk of ALD and progression to cirrhosis and HCC [45,46]. A meta-analysis showed that GG genotype had approximately a four-fold risk of having alcohol-related cirrhosis when compared with the CC genotype [47]. The fact that PNPLA3 variant is more frequent in people with indigenous ancestry explains in part the high prevalence of liver cirrhosis in Latin-America [48]. In a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS), PNPLA3 has been confirmed as the main risk locus for alcohol-related cirrhosis. Variations in two other genes (i.e. TM6SF2 and MBOAT7) also confer risk for severe ALD. These two genes, along with PNPLA3, are related to lipid metabolic processes [49,50]. The TM6SF2 and PNPLA3 polymorphism variants apparently have a role on the modulation of hepatic fat accumulation, fibrosis and HCC development. The MBOAT7 polymorphism has been associated mainly with fibrosis [51–53]. Recently, it has been also described the a splice variant in HSD17B13, encoding the hepatic lipid droplet protein hydroxysteroid 17-beta dehydrogenase 17, which appeared to protect against alcohol-associated and non-alcohol associated steatohepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [54].

Recommendations/key concepts

- 2.

The amount of alcohol consumed is the most important risk factor for the development of ALD (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 3.

Subjects consuming more than 3 standard drinks per day in men, and more than 2 drinks per day in women, or repeated binge drinking (defined as more than 5 drinks in men and more than 4 in women over a 2h period) are at risk of developing liver disease and should receive counseling (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 4.

The impact of the type of alcoholic drink consumed (i.e. liquor, beer or wine) and the pattern of drinking on the risk of developing ALD is not well known (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 5.

Patients with any chronic liver disease and protein calorie malnutrition should be advised to avoid regular alcohol consumption (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 3.

Studies assessing the impact of the type of alcohol consumed in ALD.

- 4.

Large genome wide association studies, in different ethnicities of Latin-America, to identify the genetic determinants implicated in individual susceptibility to ALD.

- 5.

Studies assessing the role of environmental factors influencing the susceptibility to develop severe ALD.

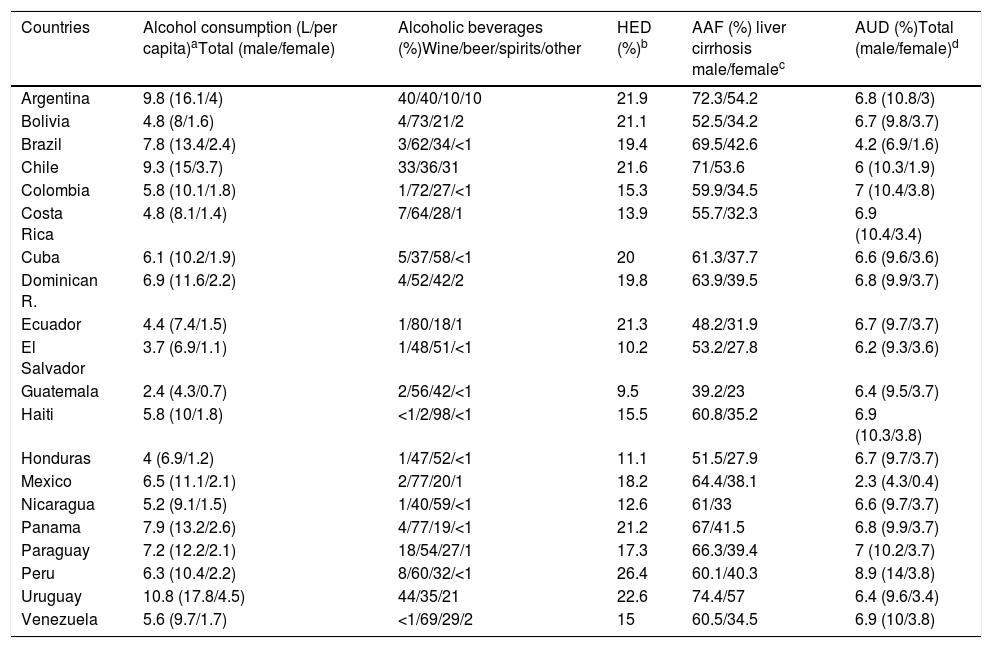

Alcohol is one of the five main factors responsible for disease, death and disability worldwide. In 2016, 3 million people died due to alcohol-related causes, which represents 5.3% of all deaths [5]. ALD is one of the most important consequences of chronic alcohol drinking and represents the main cause of cirrhosis worldwide. Globally, alcohol-attributable fraction (AAF) of liver cirrhosis is up to 50%. In Latin-America, excessive alcohol consumption and its consequences represent a major public health problem. Even though studies from the region are scarce, and there is great variability among Latin-American countries, the magnitude of the problem can be assessed through the WHO Global Alcohol database [5]. Latin-America consists of 20 countries comprising 58% of the population of the Region of the Americas. In terms of alcohol consumption, the Region of the Americas ranks second following the European Region. The total per capita pure alcohol consumption per year in 2016 in the Region of the Americas was 8.0l compared to 6.2l worldwide.

About 43% of adults in the world are current drinkers, defined as those people who have consumed alcohol within the last 12 months. Among Latin American countries such as Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Peru and Colombia current drinkers are more than 80%, and in Argentina, Chile and Peru more than 60% are current drinkers, in both cases considering men and women. In Argentina, Chile and Uruguay the average of standard drinks per day are 2–3 in women. Meanwhile, men from Paraguay, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and Mexico are 3–4 standard drinks daily [55]. The countries in Latin-America with highest alcohol consumption (L/per capita) are Uruguay, Argentina and Chile and the countries with lower consumption are Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras (Table 2). Of note, the consumption of homemade alcoholic beverages, very typical in rural areas in Latin America, is unknown and may account for an important and unrecorded proportion of alcohol intake.

Epidemiological data for Latin-American.

| Countries | Alcohol consumption (L/per capita)aTotal (male/female) | Alcoholic beverages (%)Wine/beer/spirits/other | HED (%)b | AAF (%) liver cirrhosis male/femalec | AUD (%)Total (male/female)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 9.8 (16.1/4) | 40/40/10/10 | 21.9 | 72.3/54.2 | 6.8 (10.8/3) |

| Bolivia | 4.8 (8/1.6) | 4/73/21/2 | 21.1 | 52.5/34.2 | 6.7 (9.8/3.7) |

| Brazil | 7.8 (13.4/2.4) | 3/62/34/<1 | 19.4 | 69.5/42.6 | 4.2 (6.9/1.6) |

| Chile | 9.3 (15/3.7) | 33/36/31 | 21.6 | 71/53.6 | 6 (10.3/1.9) |

| Colombia | 5.8 (10.1/1.8) | 1/72/27/<1 | 15.3 | 59.9/34.5 | 7 (10.4/3.8) |

| Costa Rica | 4.8 (8.1/1.4) | 7/64/28/1 | 13.9 | 55.7/32.3 | 6.9 (10.4/3.4) |

| Cuba | 6.1 (10.2/1.9) | 5/37/58/<1 | 20 | 61.3/37.7 | 6.6 (9.6/3.6) |

| Dominican R. | 6.9 (11.6/2.2) | 4/52/42/2 | 19.8 | 63.9/39.5 | 6.8 (9.9/3.7) |

| Ecuador | 4.4 (7.4/1.5) | 1/80/18/1 | 21.3 | 48.2/31.9 | 6.7 (9.7/3.7) |

| El Salvador | 3.7 (6.9/1.1) | 1/48/51/<1 | 10.2 | 53.2/27.8 | 6.2 (9.3/3.6) |

| Guatemala | 2.4 (4.3/0.7) | 2/56/42/<1 | 9.5 | 39.2/23 | 6.4 (9.5/3.7) |

| Haiti | 5.8 (10/1.8) | <1/2/98/<1 | 15.5 | 60.8/35.2 | 6.9 (10.3/3.8) |

| Honduras | 4 (6.9/1.2) | 1/47/52/<1 | 11.1 | 51.5/27.9 | 6.7 (9.7/3.7) |

| Mexico | 6.5 (11.1/2.1) | 2/77/20/1 | 18.2 | 64.4/38.1 | 2.3 (4.3/0.4) |

| Nicaragua | 5.2 (9.1/1.5) | 1/40/59/<1 | 12.6 | 61/33 | 6.6 (9.7/3.7) |

| Panama | 7.9 (13.2/2.6) | 4/77/19/<1 | 21.2 | 67/41.5 | 6.8 (9.9/3.7) |

| Paraguay | 7.2 (12.2/2.1) | 18/54/27/1 | 17.3 | 66.3/39.4 | 7 (10.2/3.7) |

| Peru | 6.3 (10.4/2.2) | 8/60/32/<1 | 26.4 | 60.1/40.3 | 8.9 (14/3.8) |

| Uruguay | 10.8 (17.8/4.5) | 44/35/21 | 22.6 | 74.4/57 | 6.4 (9.6/3.4) |

| Venezuela | 5.6 (9.7/1.7) | <1/69/29/2 | 15 | 60.5/34.5 | 6.9 (10/3.8) |

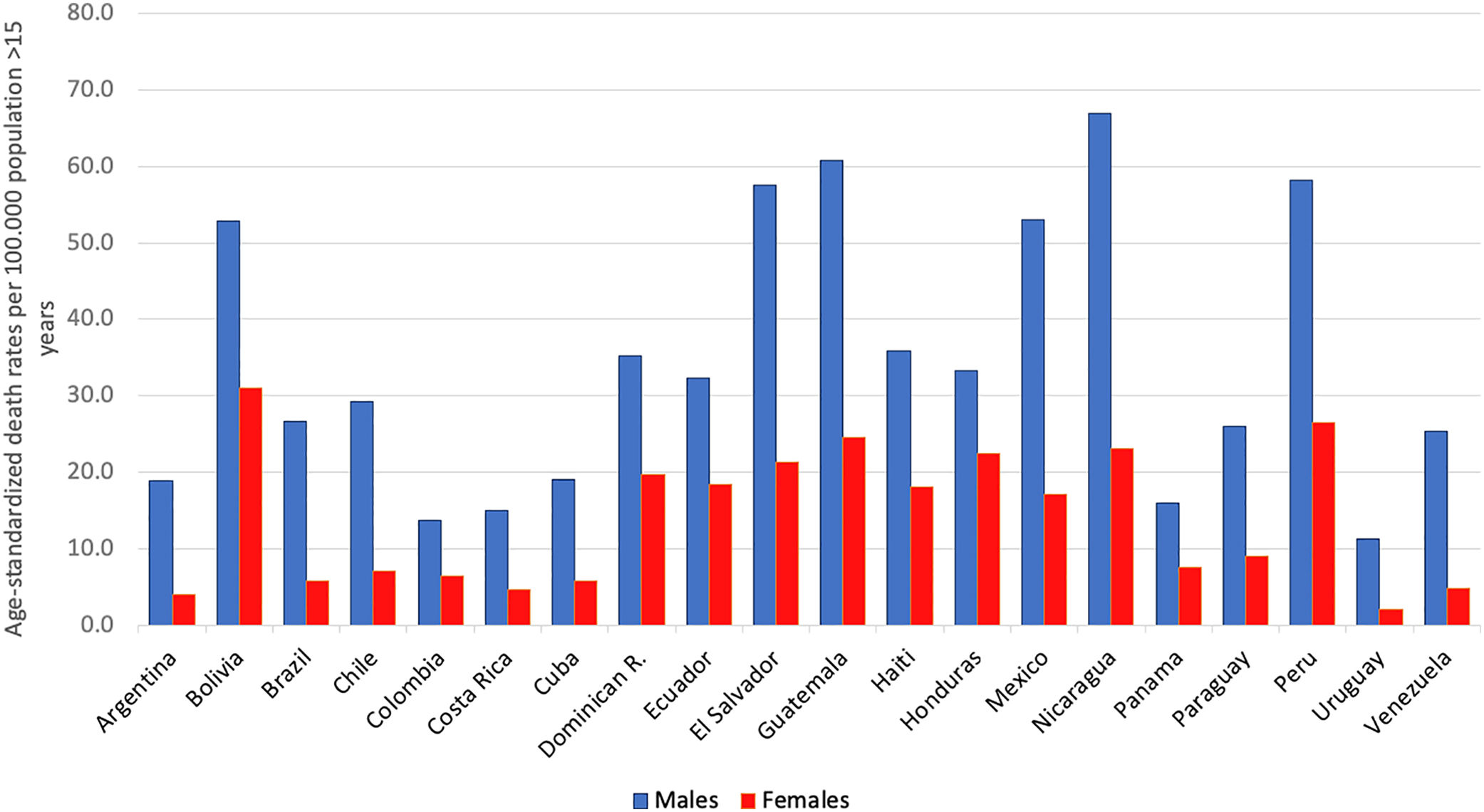

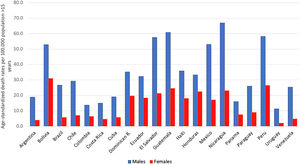

AAFs for all-cause disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and for all-cause deaths in 2016 in Latin-America were 6.7% and 5.5%, respectively [5]. The cirrhosis burden, which is caused mainly by alcohol in our region, is particularly alarming in Latin-America. In 2012, liver cirrhosis was responsible for 60,600 deaths and 1,787,000 DALYs [56]. In Latin America, and especially in the Central region of Latin America, cirrhosis causes high mortality. It is responsible of about 2.7% of all deaths, one of the highest rates in the world, being only greater in countries from the Middle East and North Africa [55] (Fig. 3).

In some countries of Latin-America consumption has increased, and this trend is expected to continue over the next 25 years, unless drastic public health measures are taken to reduce consumption [57,58]. The prevalence of AUD, alcohol dependence and harmful use of alcohol constitutes a major problem in the region. Peru is the country with the highest prevalence of AUD (8.9%). It is worthwhile to note that this percentage is higher only in some countries of Europe. In addition, Latin-America has one of the highest prevalence of AUD in the world among women, being especially high in Colombia, Haiti, Peru and Venezuela [5] (Table 2).

Regarding consumption patterns, America also has a high prevalence of heavy episodic drinking/binge drinking. There is a prevalence of 21.3% in the overall population (15 or more years of age) and 40.5% among drinkers. Peru is the country with the highest prevalence of heavy drinking/binge drinking, being 26.4% among the general population [5] (Table 2). Regarding the type of beverage consumed, the regions of South America, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay are high consumers of wine. Other Latin-American countries, for example, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Peru mostly consume spirits, followed by beer. Overall, beer is the most frequently consumed beverage in Central and South America, constituting about 50% of the total recorded alcohol consumed [5].

In Latin-America, we urge to strengthen public policies to reduce excessive alcohol consumption. This is especially important in the countries of the region where laws have not been developed yet to address this issue. In fact, at present, only eight of the twenty Latin-American countries have written national policies on alcohol [5]. Public policies such as increased taxation have proved to be effective in other countries. Also, the taxation proportional to the percentage of alcohol, for example, introducing the Minimum Unit Pricing, have shown to reduce alcohol-related diseases [59].

Recommendations/key concepts

- 6.

Latin-America is one of the regions with high prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption and the resulting health consequences represent a major public health concern. Implementation of public health policies aimed at reducing the burden of alcohol-related cirrhosis are urgently needed (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 6.

Epidemiological studies assessing the prevalence of ALD in Latin-America.

- 7.

Studies evaluating cost-effectiveness of public policies and measures to reduce alcohol consumption and the burden of ALD.

The existence of AUD should be assessed in all patients presenting with abnormal liver function tests or with liver-related complications. It is important to keep in mind that hazardous drinking refers to the drinking pattern of alcohol that increases the risk of physical harm or psychological problems. AUD refers to the harmful use of alcohol and alcohol dependence. The harmful use of alcohol corresponds to the pattern of intake that has potential to cause physical or mental harm. Alcohol dependence is defined by the WHO as a cluster of behavioral, cognitive, and physiological phenomena that develop after alcohol use. It typically includes a strong desire to consume alcohol, difficulty in controlling its use, persistent use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to alcohol use than to other activities, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physiological withdrawal state [60].

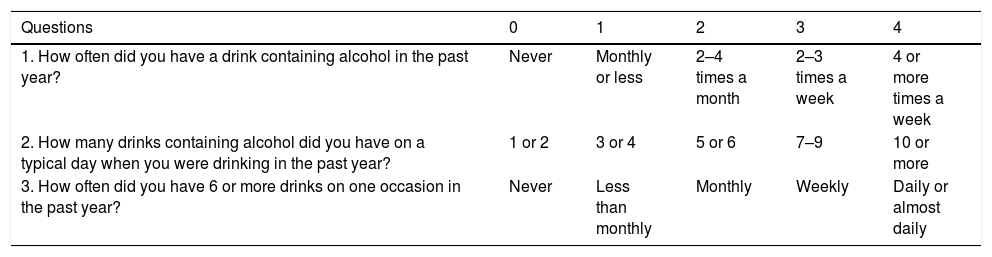

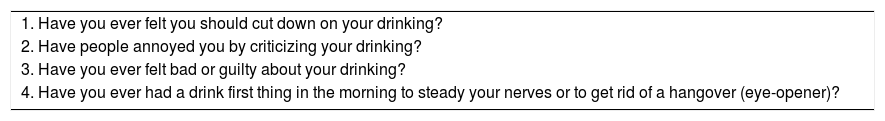

Some questionnaires can help us to distinguish patients with alcohol abuse. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) comprises ten questions with a specific scoring system [61]. An AUDIT score >8 is considered a positive screening test result, which indicates the presence of AUD. A score of >20 implies the presence of alcohol dependence [62]. The AUDIT-C is a shorter version of AUDIT (Table 3) that consists of three questions with a specific scoring system that ranges from 0 to 12. A positive screening result is a score of 3 or more for women and 4 or more for men. A score between 7 and 10 has been associated with an increased risk of alcohol dependence. The AUDIT-C has 73% sensitivity and 91% specificity for AUD and 85% sensitivity and 89% specificity for detecting alcohol dependence [63]. The CAGE questionnaire is also a useful and an easily applied tool (Table 4). Two or more out of the four possible “yes” responses indicate that the possibility of AUD should be investigated further [64]. A meta-analysis that evaluated the CAGE questionnaire using a cutoff of more than two positive responses, found an overall sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 90% [65].

AUDIT-c Questionnaire [61,63].

| Questions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. How often did you have a drink containing alcohol in the past year? | Never | Monthly or less | 2–4 times a month | 2–3 times a week | 4 or more times a week |

| 2. How many drinks containing alcohol did you have on a typical day when you were drinking in the past year? | 1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 5 or 6 | 7–9 | 10 or more |

| 3. How often did you have 6 or more drinks on one occasion in the past year? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily |

The AUDIT-c questionnaire is scored on a scale of 0–12. In men, a score of 4 or more is considered positive, optimal for identifying hazardous drinking or active alcohol use disorders. In women, a score of 3 or more is considered positive. However, when the points are all from Question #1 alone (and #2 and #3 are zero), it can be assumed that the patient is drinking below recommended limit s and it is suggested that the physician review the patient's alcohol intake over the past few years to confirm accuracy.

The CAGE Questionnaire [64].

| 1. Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking? |

| 2. Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| 3. Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking? |

| 4. Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (eye-opener)? |

Scoring: Each response is scored as 0 or 1, with a higher score indicative of alcohol-related problems, and a total of ≥2 clinically significant.

The diagnosis of ALD relies on a history of significant alcohol intake, clinical features, laboratory abnormalities and on excluding other causes of liver disease. Aminotransferases can be slightly or moderately elevated, but usually serum values are less than 300–400IU/L. The ratio of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level is generally greater than 2. This ratio is due to reduced hepatic ALT activity, alcohol-induced depletion of hepatic pyridoxal 5’-phosphate and an increased hepatic mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase [65]. Other typical laboratory abnormalities are elevation of GGT and of mean corpuscular volume. Imaging studies, such as ultrasound, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are non-specific for diagnosis of ALD. However, they are useful to search for characteristic findings of fatty liver, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and also for differential diagnosis with biliary tract diseases. The differential diagnosis between ALD and NAFLD in patients with both risk factors is challenging. A cross-sectional cohort study performed at the Mayo Clinic identified the mean corpuscular volume, AST/ALT ratio, body mass index, and gender as the most important variables that differentiate patients with ALD from those with NAFLD. These variables were used to generate the ALD/NAFLD Index (ANI) [66]. In many patients, however, ALD and NAFLD coexist. A new nomenclature defining the combined etiology should be developed.

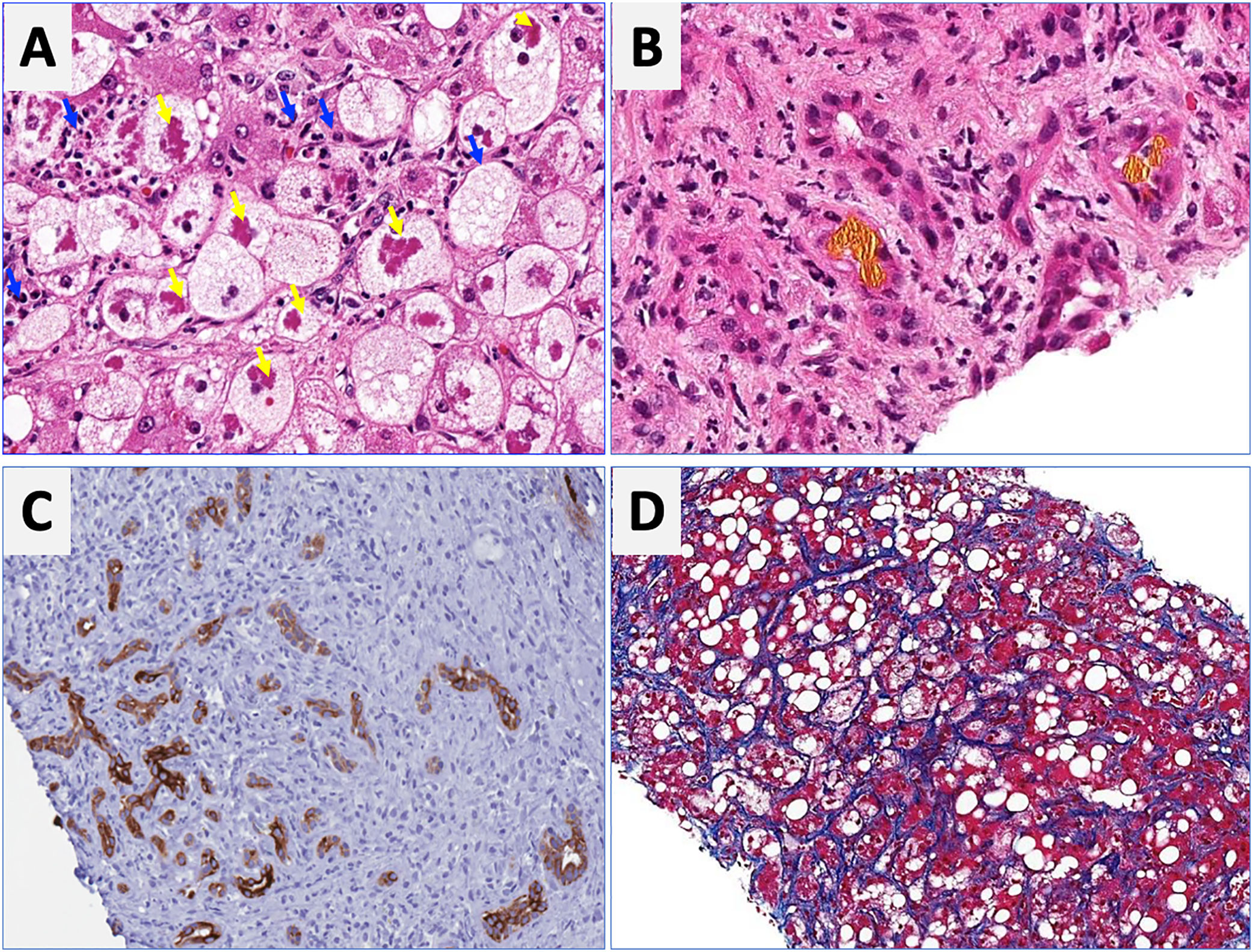

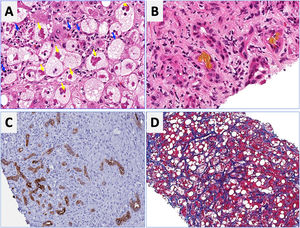

Although the diagnosis of ALD is clinico-pathological, a liver biopsy helps to establish the diagnosis and to exclude coexisting conditions. However, in clinical practice the diagnosis is often made without recourse to a biopsy. The histological features of ALD can vary, depending on the extent and stage of injury and are not pathognomonic for ALD. Macrovesicular steatosis is the earliest and most commonly seen pattern. Cirrhosis may occur after a median of 10.5 years in 10% of patients with steatosis. In patients with ASH, the main findings are steatosis, hepatocellular injury characterized by ballooned hepatocytes that often contain amorphous eosinophilic inclusions called MDB surrounded by neutrophils, intra-sinusoidal fibrosis, also perivenular and/or periportal fibrosis, and cirrhosis. In addition to these features, AH is characterized by intraparenchymal cholestasis or bilirubinostasis [59]. Other histologic findings associated with AH may include megamitochondria, foamy degeneration of hepatocytes and acute sclerosing hyaline necrosis [63,67].

Fibrosis is one of the main prognostic factors, and in the absence of a biopsy, non-invasive methods to assess fibrosis in ALD have been developed [68]. Some alternatives are commercially available serum biomarkers, such as Fibrotest®, Fibrometer®, and Hepascore®. The diagnostic accuracy of these tests is greater than other biomarkers developed for viral hepatitis (i.e. APRI, Forn's Index, FIB4) [59]. A combination of any of these tests was not useful in improving diagnostic performance [69]. Another noninvasive approach is the use of transient elastography, which assesses liver stiffness. Liver stiffness measurement (LSM) closely correlates with the degree of fibrosis and is excellent to exclude significant fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients first assessed for ALD [70,71]. The cutoff values for F3 and F4 were considerably higher when compared to patients with viral hepatitis. Confounding factors that can interfere with LSM include AST>200UI/L [72], recent alcohol intake, no compliance with fasting recommendation before the assessment and the presence of cholestasis [73]. Recently, Magnetic Resonance Elastography (MRE) has been shown to be an excellent tool to evaluate the elasticity of the liver tissue, with, according to recent studies, an accuracy equal to or superior to TE for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, regardless of the etiology. It has the advantage that it carries out an evaluation of all the liver tissue and that it can be done in a two-dimensional and even three-dimensional way [74]. However, it is a high cost test, which is a problem for use in Latin American countries.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 7.

Alcohol use disorder should be assessed in all patients presenting with newly recognized liver disfunction, by application of specific questionnaires (i.e. AUDIT or CAGE) that can be easily applied in daily clinical practice (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 8.

In patients with AUD, clinical, biochemical and radiological evaluation is mandatory for early detection of underlying ALD (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 9.

A liver biopsy may be considered when the ALD diagnosis is unclear due to the existence of other potential etiological factors (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: weak).

- 10.

In patients with excessive alcohol use and obesity-related metabolic syndrome, the Alcoholic liver disease/Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Index (ANI) could be helpful in differentiating ALD and NAFLD (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 11.

Liver stiffness measurement or patented serum biomarkers may be useful for assessing liver fibrosis in patients with ALD, however, certain conditions, such as the presence of ASH, cholestasis, and active alcohol intake can overestimate the degree of fibrosis (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 8.

Studies to identify reliable noninvasive biomarkers to differentiate between steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis in the setting of ALD.

- 9.

Population based studies to assess the prevalence of AUD and ALD in Latin-America.

Alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is a clinical entity characterized by abrupt onset of jaundice, and liver-related decompensation in patients with excessive and prolonged alcohol consumption. It should not be confused with early ASH that is detectable through histology in patients with silent disease. AH manifests with rapid onset of progressive jaundice, leukocytosis and right upper quadrant abdominal discomfort. This may transition to a more severe hepatic injury, including acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and multi-organ failure, which carry a mortality risk of 18–50% in 1 month depending on the number of comprised extra-hepatic organs [11].

Regarding laboratory tests, AST levels are typically elevated (2–6 times ULN) with AST/ALT ratio>2. Hyperbilirubinemia and leukocytosis are also frequently observed. In severe cases, serum albumin may be decreased, and the INR elevated. Patients with severe forms of AH are prone to develop bacterial infections and acute renal injury [67]. An NIH-sponsored consensus meeting of investigators recently proposed the following criteria for clinical diagnosis: (1) heavy alcohol use for >6 months (typically>5 years), (2) active alcohol use until <60 days prior to presentation, (3) sudden onset or worsening of jaundice, (4) AST/ALT ratio>1.5:1 with levels<400IU/L, and (5) absence of other causes of liver disease [75]. Histologically, AH is associated with ballooned hepatocytes, MDB, lobular polymorphonuclear neutrophils and pericellular, bilirrubinostasis and sinusoidal fibrosis (“chicken wire” appearance) (Fig. 4). The lesions defining ASH do not differ in essence from those described in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [7]. In patients with suspected AH, a transjugular liver biopsy is recommended when the clinical diagnosis is confounded by another liver disease etiology, in the presence of confounding factors or when the alcohol consumption history is uncertain.

Characteristic histological findings in alcoholic hepatitis. Macrovesicular steatosis is the earliest and most common seen pattern. Hepatocellular injury is characterized by lobular infiltration of neutrophils (Panel A, blue arrows) with ballooned hepatocytes that often contain amorphous eosinophilic inclusions called Mallory-Denk bodies (Panel A, yellow arrows), bilirubinostasis (Panel B), ductular reaction (C) and liver fibrosis, which is typically described as pericellular and sinusoidal (“chicken wire” appearance) (Panel D).

Multiple scoring systems have been developed to predict short-term prognosis in patients with AH. One of the first and most validated is the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF), which includes prothrombin time (PT) and total bilirubin, and where severe AH is defined by a score ≥32 [76]. This score was used in the original trial assessing corticosteroids treatment of AH. A MDF score ≥32 predicts a 30-day mortality rate of approximately 20–50% [77]. Many other scoring systems have also been validated. These include the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) and the Age, serum Bilirubin, INR, and serum Creatinine (ABIC) [77]. The MELD score is being increasingly used to assess severity of AH given its better accuracy, worldwide use in organ allocation and use of INR as standard in reporting prothrombin time. It also incorporates renal function/serum creatinine, which is a major determinant of outcomes in AH patients. A MELD score >20 has been proposed as defining severe AH [78]. The ABIC score classifies patients according to low, intermediate and high risk for death [79]. Another relevant prognostic tool is the Lille score, which is a continuous score with a scale from 0 to 1, assessed at 4–7 days of corticosteroid therapy. A Lille score <0.45 predicts a favorable response to corticosteroids and continuation of prednisolone for a total of 4 weeks is recommended [80]. The vast majority of these scores have been shown to predict prognosis accurately at 30 days but have failed in predicting survival beyond 90 days. The strongest predictor of survival after 90 days is the ability to maintain abstinence from alcohol [81]. A very interesting recent study showed that a combining the MELD score at baseline and the Lille score at day 7 performs best for prognostication of 2-month and 6-month mortality [82]. Another recent study showed that MELD, ABIC and GAHS are superior to the DF in AH. Furthermore, in combination with the Lille score, this allows for a reduction in the number of patients treated unnecessarily with corticosteroids, leading to an improvement in survival at 90 days [83]. Multiple other criteria and biomarkers have been recently proposed and need further validation, including serum lipopolysaccharide levels, SIRS criteria, and procalcitonin [84]. Further studies should evaluate the performance of the existing prognostic scoring systems in Latin America.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 12.

AH is clinically defined as abrupt onset of progressive jaundice and liver-related complications with hyperbilirubinemia (>3mg/dL), AST/ALT ratio>1.5 with levels of AST>1.5 times the upper limit of normal but <400IU/L; and heavy alcohol drinking until 60 days before onset of symptoms and absence of other causes of liver disease (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 13.

Liver biopsy to diagnose AH is recommended in patients with suspected AH, but who do not meet the abovementioned criteria, in the presence of confounding factors or when other etiology is also suspected (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 10.

Studies assessing the clinical features, mortality and usefulness of existing scoring systems in Latin-America.

- 11.

Studies assessing noninvasive biomarkers useful to diagnose AH and to predict survival and response to therapy.

- 12.

Studies assessing the prevalence and predictors of alcohol relapse and its impact on long-term outcome in patients surviving an episode of AH.

Alcohol is the main etiology of cirrhosis worldwide including Latin-America [1]. Cirrhosis is the most important risk factor for HCC development. A multicenter prospective study, from Latin-America, reported that 85% of HCC patients had underlying cirrhosis [85]. HCC association with cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis B and C infections, and hemochromatosis is stronger than with cirrhosis related to ALD, where the association is less intense [86]. The population-attributable fractions are greatest for metabolic disorders (32%), followed by hepatitis C virus (HCV) (20.5%), and alcohol (13.4%) [87]. Multiple studies have shown cumulative risk of HCC higher than 1.5% per year, which represents the threshold proposed for HCC surveillance, so HCC screening is recommended in all patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis [88,89]. To date, no Latin-American studies aimed at assessing this issue have been published.

The amount of alcohol ingestion has been shown to affect, although not in a linear fashion, the development of cirrhosis and HCC. Higher intake confers higher risk of HCC, but there is no established threshold [90]. There are no data on the role of the duration or pattern of drinking (continuous versus binge) on HCC development. Regarding other risk factors, women have higher incidence of cirrhosis and HCC with lower levels of alcohol ingestion [90]. Genetic polymorphisms also affect the predisposition to HCC in ALD. The PNPLA3 gene polymorphism (C>G) increases the risk of HCC with an OR of 2.20 (1.80–2.67) for G allele [91]. These results might have a great impact in Latin-America, where GG polymorphism is frequently seen [92]. Finally, cigarette smoking significantly increases the risk of developing HCC [93].

Multiple studies have shown that chronic hepatitis B and C infections act synergistically with alcohol in the progression, risk and incidence of HCC [94]. In Latin-America, HBsAg prevalence is lower than other developing regions and it has recently dropped probably due to vaccination programs. Nevertheless, there are still some regions of the Amazonia with high prevalence (>8%). Meanwhile, chronic hepatitis C prevalence in the region is similar to Europe or the United States [95].

Surveillance for HCC should not be different in ALD related cirrhosis in Latin-America compared to other etiologies. ALEH guidelines recommend liver ultrasonography every 6 months and to consider serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) as a biomarker [96]. Patients with ALD are less frequently screened and have less adherence. As a consequence, HCC is diagnosed at advanced stages in this patient population and carry lower survival rates. However, after adjusting for disease stage, the natural history and survival are similar to other causes of HCC [97].

Recommendations/key concepts

- 14.

Alcohol-related cirrhosis is one of the main causes of HCC in Latin-America (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 15.

The risk of HCC in ALD-related cirrhosis is similar to other etiologies and surveillance should be performed by ultrasonography every 6 months with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein levels (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 13.

Epidemiological studies focusing on the risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma and their impact on its development in Latin-America, with a special emphasis on ALD.

- 14.

Studies assessing the role of genetic/epigenetics on the predisposition to development of HCC in alcohol-related cirrhosis.

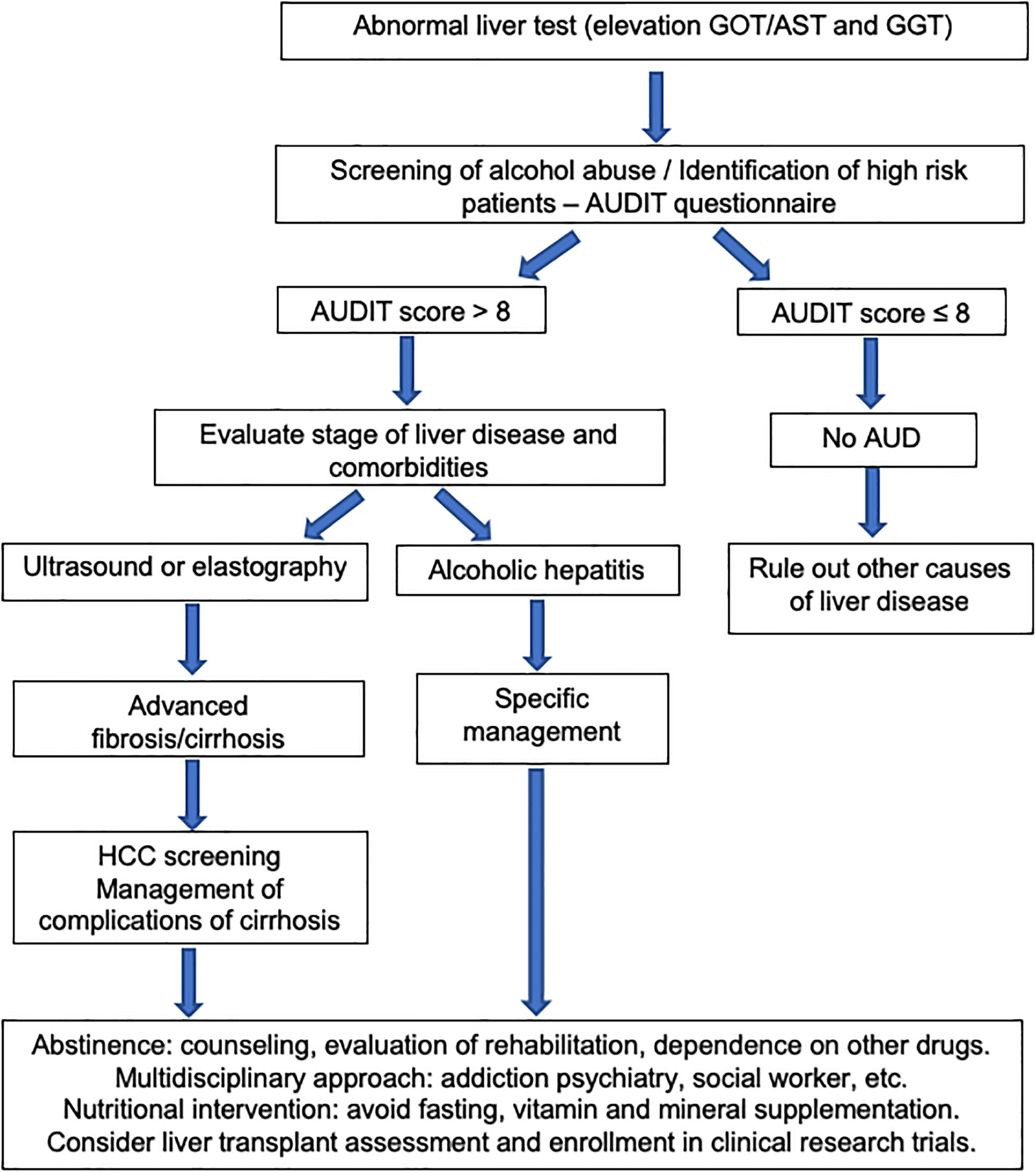

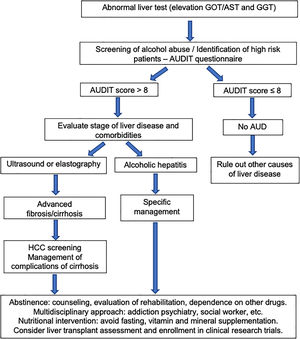

The first step in management of ALD should be directed to an early recognition of excessive alcohol intake by both the patient and the physician. Patients often underreport alcohol intake and a motivational and empathetic relationship with the provider is highly advised. It is recommended that physicians taking care of these patients also get some training in motivational interviewing and addiction medicine. In fact, a proportion of alcohol abusers many times also consume other drugs [98]. The current long-term management of alcohol-related cirrhosis should focus on: alcohol abstinence, aggressive nutritional therapy rich in calories and proteins, and prevention/early therapy of cirrhosis complications (i.e. variceal bleeding and HCC). Fig. 5 summarizes an algorithm for diagnosis and management of ALD and AUD.

Achieving prolonged alcohol abstinence is the main therapeutic goal in all patients with ALD regardless of the stage. Abstinence decreases morbidity and mortality from alcohol both in patients with early and advanced ALD [81,99]. A remarkable aspect of heavy alcohol consumption is the tendency for relapse after both long and short periods of abstinence. Of patients that survive an episode of AH, more than 60% patients relapse. In many cases, alcohol relapse occurs years after the index episode of an AH. After surviving the acute inflammatory syndrome of AH, the intermediate and long-term prognosis is governed by abstinence or relapse [81].

8.1.1.1Psychosocial therapy and behavioral treatmentBrief motivational interventions lasting no more than 5–10min are useful and recommended in all patients with ALD and active drinking. The main goals of these interventions are to educate the patient about the impact of alcohol and to stimulate their desire to discontinue alcohol intake. Although these interventions alone are not sufficient to impact alcohol dependence in heavy drinkers, they might reinforce compliance to medication [100]. Specific psychological and behavioral therapies should be kept in mind as important tools to identify triggers resulting in relapse and for modifying maladaptive behavior. This includes facilitating 12 steps, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and motivational enhancement therapy (MET). This twelve-step facilitation intervention is abstinence-based and involves participation of the patient in alcoholic anonymous (AA) meetings. MET is intended to find a framework for modifying alcohol intake and to help these patients work on developing resistance and to change alcoholic habits. CBT focuses on identifying triggers that compulsively lead to resuming alcohol intake. This approach tends to replace old alcoholism promoting behaviors that lead the patient to consume alcohol and replace them with alcohol-free behaviors. Since none of the psychosocial interventions alone have proved to be efficient in maintaining abstinence, the combination of the two approaches (i.e. CBT and MET) is useful to increase abstinence rates [100].

8.1.1.2Pharmacological therapyPharmacological treatment is useful to prevent relapse in patients with AUD. However, few studies have assessed the efficacy and safety of anti-craving drugs in patients with ALD [90] (Table 5). In particular, naltrexone and acamprosate, two FDA-approved drugs for AUD, have not specifically been tested in ALD patients. Moreover, other commonly used drugs such as disulfiram can cause severe hepatotoxicity and are contraindicated in patients with ALD. Drugs such as topiramate, gabapentin, ondansetron, and varenicline can be useful as anti-craving drugs in patients with AUD and are probably safe in patients with ALD, although further studies are warranted before they can be recommended to ALD patients. Baclofen, a GABA receptor agonist, is the only anti-craving drug tested in a controlled trial in patients with severe ALD [101]. In a placebo-controlled trial, baclofen was useful and safe to prevent relapse in alcohol-related cirrhotics. Therefore, although further studies are needed, this medication has shown to be useful for therapy in patients with severe ALD. Robust clinical trials testing the role of drugs in ALD and exploring combinations of pharmacologic and behavioral treatment in AUD in the setting of ALD are lacking [102].

Proposed medications to treat alcohol use disorders in cirrhotic patients.

| Proven to be safe and efficient in ALD |

| Baclofen (10mg TID; 80mg QD max) |

| Probably safe but not proven in ALD patients |

| Acamprosate (666mg TID) |

| Naltrexone (PO: 50mg QD IM: 380mg monthly) |

| Nalmefene (Max daily dose: 1 tablet 18mg) |

| Topiramate (300mg QD) |

| Gabapentin (900–1800mg QD) |

| Varenicline (2mg QD) |

| Ondansetron (1–16mcg/kg BID) |

| Contraindicated medications in cirrhosis |

| Disulfiram |

Malnutrition with and without sarcopenia is common among patients with ALD [103]. Although alcohol is a high-calorie power beverage, alcohol intake provides empty calories. More than 50% of patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis have some degree of protein-calorie malnutrition. Complications of portal hypertension (i.e. variceal bleeding, encephalopathy and ascites) and sepsis are also more commonly observed in malnourished cirrhotic patients [103]. Increased catabolism, decreased food intake due to alcoholic gastritis and esophagitis, diarrhea induced by malabsorption, pancreatic insufficiency, and complications of cirrhosis, such as encephalopathy, contribute to malnutrition in ALD. Most studies aimed at assessing a beneficial effect of parenteral nutritional supplementation in ALD have shown disappointing results. A limited number of patients and a short period of treatment were the main causes of failure for these trials [104]. However, enteral nutritional support increases survival when nutritional status was assessed through several reliable tools in clinical practice, such as nitrogen balance, and anthropometric variables [104]. Most of the current guidelines recommend a protein intake of 1.2–1.5g of protein per kg of body weight and a calorie intake of 30–35kcal per kg of body weight, including late-evening snack. During cirrhosis decompensations, a maximum protein intake (i.e., 1.5g per kg of body weight) and 40kcal per kg of body weight should be indicated, since it has been shown to improve caloric malnutrition [105]. Finally, it is important to note that patients with ALD usually have vitamins and micronutrients deficiency. Vitamins (i.e. thiamine, folate, pyridoxine and cyanocobalamin) and minerals (i.e. potassium, phosphate, magnesium and zinc) should be measured and/or supplemented as needed (Tables 6 and 7).

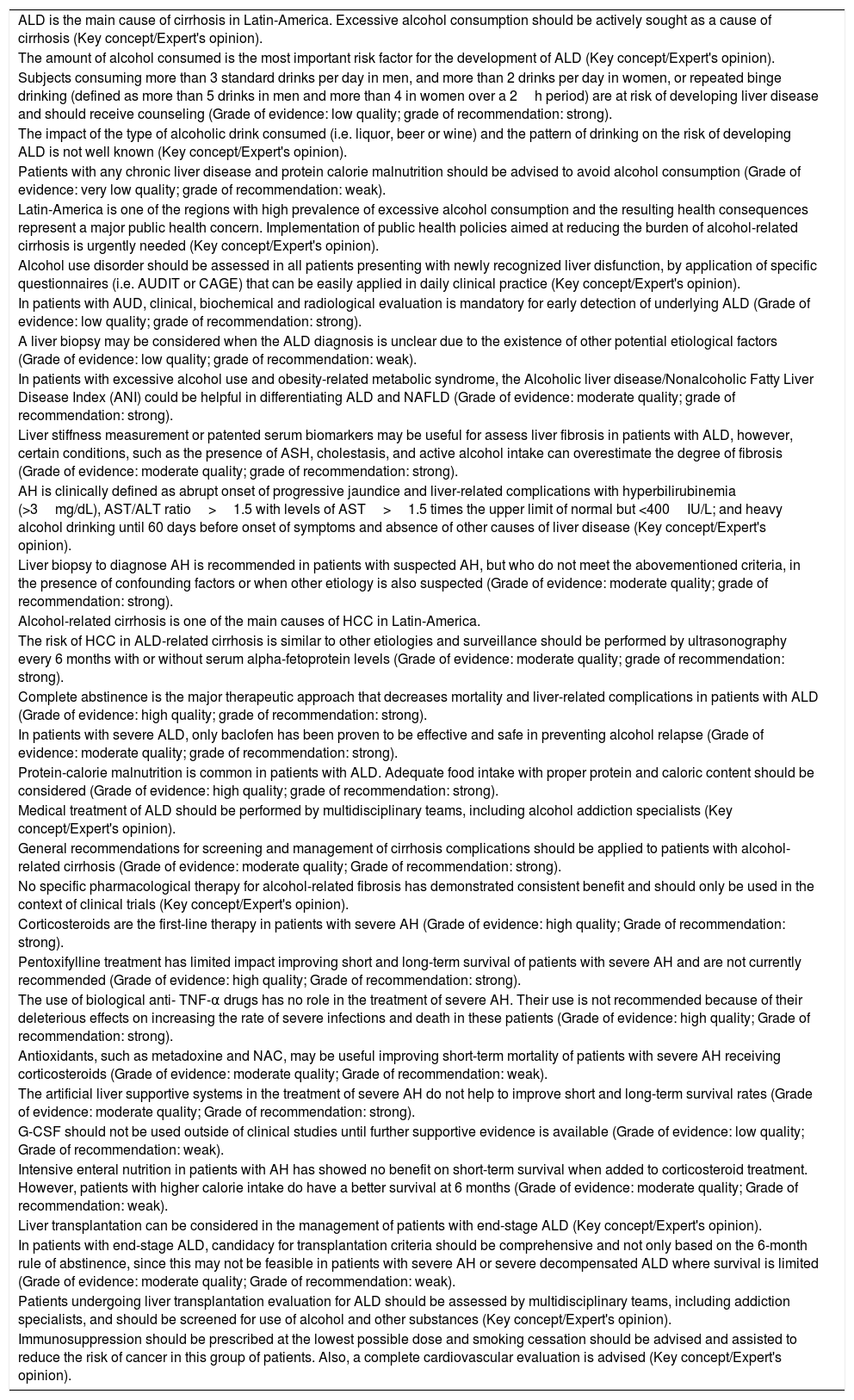

Recommendations and key concepts on the management of alcohol-related liver disease.

| ALD is the main cause of cirrhosis in Latin-America. Excessive alcohol consumption should be actively sought as a cause of cirrhosis (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| The amount of alcohol consumed is the most important risk factor for the development of ALD (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Subjects consuming more than 3 standard drinks per day in men, and more than 2 drinks per day in women, or repeated binge drinking (defined as more than 5 drinks in men and more than 4 in women over a 2h period) are at risk of developing liver disease and should receive counseling (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| The impact of the type of alcoholic drink consumed (i.e. liquor, beer or wine) and the pattern of drinking on the risk of developing ALD is not well known (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Patients with any chronic liver disease and protein calorie malnutrition should be advised to avoid alcohol consumption (Grade of evidence: very low quality; grade of recommendation: weak). |

| Latin-America is one of the regions with high prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption and the resulting health consequences represent a major public health concern. Implementation of public health policies aimed at reducing the burden of alcohol-related cirrhosis is urgently needed (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Alcohol use disorder should be assessed in all patients presenting with newly recognized liver disfunction, by application of specific questionnaires (i.e. AUDIT or CAGE) that can be easily applied in daily clinical practice (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| In patients with AUD, clinical, biochemical and radiological evaluation is mandatory for early detection of underlying ALD (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| A liver biopsy may be considered when the ALD diagnosis is unclear due to the existence of other potential etiological factors (Grade of evidence: low quality; grade of recommendation: weak). |

| In patients with excessive alcohol use and obesity-related metabolic syndrome, the Alcoholic liver disease/Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Index (ANI) could be helpful in differentiating ALD and NAFLD (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Liver stiffness measurement or patented serum biomarkers may be useful for assess liver fibrosis in patients with ALD, however, certain conditions, such as the presence of ASH, cholestasis, and active alcohol intake can overestimate the degree of fibrosis (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| AH is clinically defined as abrupt onset of progressive jaundice and liver-related complications with hyperbilirubinemia (>3mg/dL), AST/ALT ratio>1.5 with levels of AST>1.5 times the upper limit of normal but <400IU/L; and heavy alcohol drinking until 60 days before onset of symptoms and absence of other causes of liver disease (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Liver biopsy to diagnose AH is recommended in patients with suspected AH, but who do not meet the abovementioned criteria, in the presence of confounding factors or when other etiology is also suspected (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Alcohol-related cirrhosis is one of the main causes of HCC in Latin-America. |

| The risk of HCC in ALD-related cirrhosis is similar to other etiologies and surveillance should be performed by ultrasonography every 6 months with or without serum alpha-fetoprotein levels (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Complete abstinence is the major therapeutic approach that decreases mortality and liver-related complications in patients with ALD (Grade of evidence: high quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| In patients with severe ALD, only baclofen has been proven to be effective and safe in preventing alcohol relapse (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition is common in patients with ALD. Adequate food intake with proper protein and caloric content should be considered (Grade of evidence: high quality; grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Medical treatment of ALD should be performed by multidisciplinary teams, including alcohol addiction specialists (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| General recommendations for screening and management of cirrhosis complications should be applied to patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: strong). |

| No specific pharmacological therapy for alcohol-related fibrosis has demonstrated consistent benefit and should only be used in the context of clinical trials (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Corticosteroids are the first-line therapy in patients with severe AH (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Pentoxifylline treatment has limited impact improving short and long-term survival of patients with severe AH and are not currently recommended (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong). |

| The use of biological anti- TNF-α drugs has no role in the treatment of severe AH. Their use is not recommended because of their deleterious effects on increasing the rate of severe infections and death in these patients (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong). |

| Antioxidants, such as metadoxine and NAC, may be useful improving short-term mortality of patients with severe AH receiving corticosteroids (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak). |

| The artificial liver supportive systems in the treatment of severe AH do not help to improve short and long-term survival rates (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: strong). |

| G-CSF should not be used outside of clinical studies until further supportive evidence is available (Grade of evidence: low quality; Grade of recommendation: weak). |

| Intensive enteral nutrition in patients with AH has showed no benefit on short-term survival when added to corticosteroid treatment. However, patients with higher calorie intake do have a better survival at 6 months (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak). |

| Liver transplantation can be considered in the management of patients with end-stage ALD (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| In patients with end-stage ALD, candidacy for transplantation criteria should be comprehensive and not only based on the 6-month rule of abstinence, since this may not be feasible in patients with severe AH or severe decompensated ALD where survival is limited (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak). |

| Patients undergoing liver transplantation evaluation for ALD should be assessed by multidisciplinary teams, including addiction specialists, and should be screened for use of alcohol and other substances (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

| Immunosuppression should be prescribed at the lowest possible dose and smoking cessation should be advised and assisted to reduce the risk of cancer in this group of patients. Also, a complete cardiovascular evaluation is advised (Key concept/Expert's opinion). |

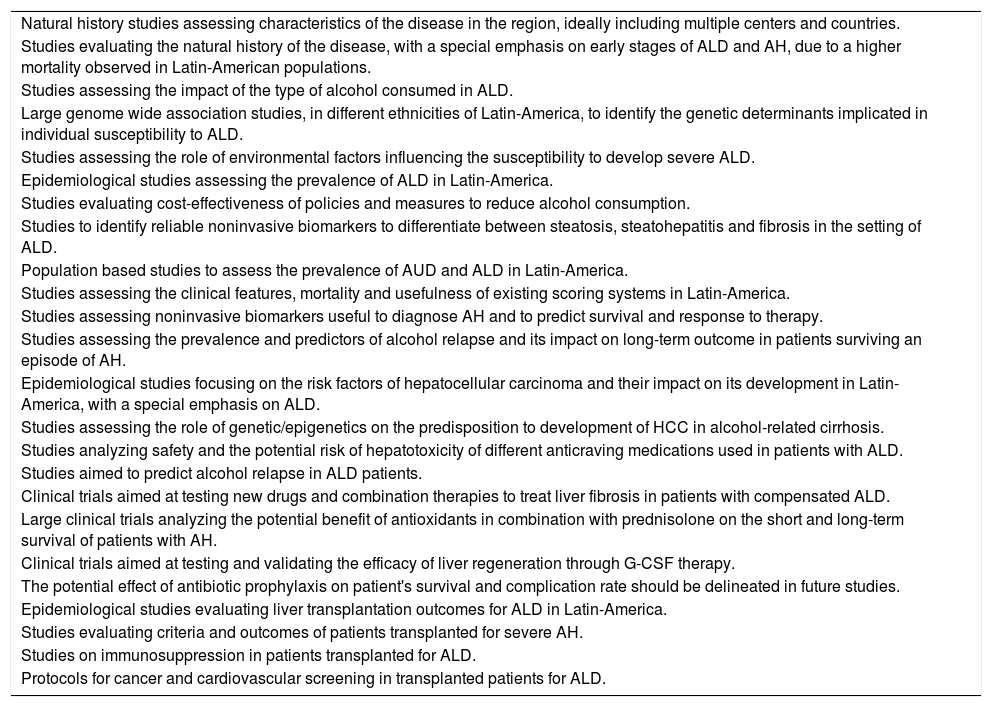

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America regarding Alcohol-related liver disease.

| Natural history studies assessing characteristics of the disease in the region, ideally including multiple centers and countries. |

| Studies evaluating the natural history of the disease, with a special emphasis on early stages of ALD and AH, due to a higher mortality observed in Latin-American populations. |

| Studies assessing the impact of the type of alcohol consumed in ALD. |

| Large genome wide association studies, in different ethnicities of Latin-America, to identify the genetic determinants implicated in individual susceptibility to ALD. |

| Studies assessing the role of environmental factors influencing the susceptibility to develop severe ALD. |

| Epidemiological studies assessing the prevalence of ALD in Latin-America. |

| Studies evaluating cost-effectiveness of policies and measures to reduce alcohol consumption. |

| Studies to identify reliable noninvasive biomarkers to differentiate between steatosis, steatohepatitis and fibrosis in the setting of ALD. |

| Population based studies to assess the prevalence of AUD and ALD in Latin-America. |

| Studies assessing the clinical features, mortality and usefulness of existing scoring systems in Latin-America. |

| Studies assessing noninvasive biomarkers useful to diagnose AH and to predict survival and response to therapy. |

| Studies assessing the prevalence and predictors of alcohol relapse and its impact on long-term outcome in patients surviving an episode of AH. |

| Epidemiological studies focusing on the risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma and their impact on its development in Latin-America, with a special emphasis on ALD. |

| Studies assessing the role of genetic/epigenetics on the predisposition to development of HCC in alcohol-related cirrhosis. |

| Studies analyzing safety and the potential risk of hepatotoxicity of different anticraving medications used in patients with ALD. |

| Studies aimed to predict alcohol relapse in ALD patients. |

| Clinical trials aimed at testing new drugs and combination therapies to treat liver fibrosis in patients with compensated ALD. |

| Large clinical trials analyzing the potential benefit of antioxidants in combination with prednisolone on the short and long-term survival of patients with AH. |

| Clinical trials aimed at testing and validating the efficacy of liver regeneration through G-CSF therapy. |

| The potential effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on patient's survival and complication rate should be delineated in future studies. |

| Epidemiological studies evaluating liver transplantation outcomes for ALD in Latin-America. |

| Studies evaluating criteria and outcomes of patients transplanted for severe AH. |

| Studies on immunosuppression in patients transplanted for ALD. |

| Protocols for cancer and cardiovascular screening in transplanted patients for ALD. |

Recommendations for screening for varices should follow Baveno guidelines. If elastography is available, a liver stiffness<20kPa together with a platelet count>150 in a compensated patient indicates a very low risk of varices needed treatment, and endoscopy can be avoided [106]. In compensated patients with no varices at screening endoscopy, and with ongoing liver injury (i.e. active drinking), surveillance endoscopy should be repeated at 2-year intervals. In compensated patients with small varices and with ongoing liver injury (i.e. active drinking), surveillance endoscopy should be repeated at 1-year intervals. In compensated patients with no varices at screening endoscopy in whom the etiological factor has been removed (i.e. long-lasting abstinence) and who have no co-factors (i.e. obesity), surveillance endoscopy should be repeated at 3-year intervals. In compensated patients with small varices at screening endoscopy in whom the etiological factor has been removed (i.e. long-lasting abstinence) and who have no co-factors (i.e. obesity), surveillance endoscopy should be repeated at 2-year intervals [107]. Primary prophylaxis of esophageal bleeding should be performed in all patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis with either beta-blockers or variceal ligation. Secondary prophylaxis should be performed similarly to that in other etiologies of cirrhosis (with banding and betablockers, if tolerated).

8.1.4Pharmacological treatment for fibrosis/cirrhosisThe most effective therapy to treat liver fibrosis associated with ALD is permanent alcohol abstinence [68]. None of the antifibrotic drugs investigated in patients with ALD, including S-adenosyl-l-methionine, propylthiouracil, colchicine, and sylimarin have been validated enough to be recommended for clinical use. Current clinical trials to treat liver fibrosis include drugs aimed at: (1) eliminating or attenuating the underlying liver disease, (2) antagonizing receptor-ligand interactions and intracellular signaling, (3) inhibiting fibrogenesis, and (4) promoting fibrosis resolution. Currently, more than 500 trials relating to anti-fibrotic strategies are registered, and recently reviewed in detail elsewhere [108].

One of the critical issues in the development of drugs to treat alcohol liver-related disease is the “dogma” that abstinence is a sine qua non for treating patients. It is probably time to accept that patients have to be treated, even if consumption is kept, in parallel with other diseases where treatments are accepted, although patients do not comply with a change of lifestyle or losing weight, as in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 16.

Complete abstinence is the major therapeutic approach that decreases mortality and liver-related complications in patients with ALD (Grade of evidence: high quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 17.

In patients with severe ALD, baclofen has been proven to be effective and safe in preventing alcohol relapse (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 18.

Protein-calorie malnutrition is common in patients with ALD. Adequate food intake with proper protein and caloric content should be considered (Grade of evidence: high quality; grade of recommendation: strong).

- 19.

Medical treatment of ALD should be performed by multidisciplinary teams, including alcohol addiction specialists (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 20.

General recommendations for screening and management of cirrhosis complications should be applied to patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: strong).

- 21.

No specific pharmacological therapy for alcohol-related fibrosis has demonstrated consistent benefits and should only be used in the context of clinical trials (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 15.

Studies analyzing effectiveness and potential risk of hepatotoxicity of different anti-craving medications in patients with ALD.

- 16.

Studies aimed to identify factors that predict alcohol relapse in ALD patients.

- 17.

Clinical trials aimed at testing new drugs and combination therapies to treat liver fibrosis in patients with compensated ALD.

Patients with severe AH should be admitted to the hospital for management. Nutritional support includes providing adequate calorie and protein intake, as well as vitamins (i.e. thiamine, folate, and pyridoxine) and minerals (i.e. potassium, phosphate, magnesium) repletion. Vitamin B1 supplementation is recommended due to a high risk of Wernicke encephalopathy (before any carbohydrate, 200mg three times per day, preferably intravenously for 3–5 days if Wernicke is suspected, and 100mg daily by mouth for long-term supplementation). Also assess or supplement magnesium sulfate as they may be unresponsive to parenteral thiamine in the presence of hypomagnesemia. Oral intake should be started as soon as possible and a daily intake of 1.5g/kg of ideal body weight of protein should be assured. Intensive care unit admission is generally recommended in critically-ill patients (patients with septic shock, grade III–IV encephalopathy, acute variceal bleeding or severe withdrawal syndrome) [28]. Airway protection with orotracheal intubation may be necessary in patients with high grade hepatic encephalopathy or severe withdrawal syndrome. Finally, although benzodiazepines are not recommended in patients with decompensated cirrhosis, their use may be necessary to treat severe alcohol withdrawal. Short acting benzodiazepines (i.e. lorazepam) should be used.

Patients with AH are prone to develop cirrhosis complications that should be managed according to current guidelines [109–113]. Bacterial infections are frequent among patients with AH and predispose them to multiple organ failure and death [84]. Since infection is a major prognostic factor for short and long-term mortality in patients with AH [114], a complete infectious disease work-up is mandatory at admission. Diagnostic paracentesis, blood cultures, urine and sputum cultures should be obtained. In patients with high suspicion of infection, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics should be initiated. A recent study showed that the risk of developing an infection was lower in patients with AH receiving antibiotics after gastrointestinal bleeding [115]. Clinical trials evaluating the specific role of antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with AH are underway.

8.2.2Specific therapies8.2.2.1CorticosteroidsThe rationale behind using corticosteroids in AH is due to their immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects. Despite conflicting data [116–121], corticosteroids are the first-line treatment in severe AH (DF>32 points or MELD>20) [7,122]. Data from a recent network meta-analysis, including 22 randomized controlled trials, support the use of corticosteroids either alone or in combination with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), to reduce short-term mortality in patients with AH [123]. A large double-blinded multicentric trial (STOPAH trial), reported an OR for mortality at 28 days for prednisolone of 0.72 (95% CI, 0.52–1.01; P=0.06). After adjustment for baseline severity and prognostic factors, the OR in the prednisolone treated group was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.41–0.91; P=0.02). Importantly, prednisolone was not associated with a reduction in mortality beyond 28 days [124]. The contraindications for the use of corticosteroids include the presence of sepsis which is common among patients with severe AH. It is important to keep in mind that steroids increase the risk of both bacterial and fungal infections. Other relative contraindications include active gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, active tuberculosis, uncontrolled diabetes and psychosis. In summary, corticosteroids can be used in selected patients and response/complications should be assessed during treatment, for example, with Lille score.

8.2.3Other therapiesPentoxifylline is a phosphodiesterase inhibitor with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) activity. An initial study with pentoxifylline therapy in AH showed a 25% improvement in mortality rate associated with hepatorenal syndrome reduction [125]. However, data from the STOPAH trial did not confirm a survival benefit with pentoxifylline [124]. A combination of pentoxifylline with corticosteroids has also been evaluated with no evidence of survival improvement at 6-months [126]. Finally, rescue treatment by switching to pentoxifylline in patients not responding to corticosteroids at 7 days did not show benefit in 2-month survival [127].

Combination therapy with prednisolone plus NAC, a powerful antioxidant, has shown to improve 1-month survival and to reduce the rate of infections. However, when analyzing survival at 6 months, no differences were found (P=0.07) [128]. Additional confirmatory studies using this strategy are warranted.

Both infliximab (a chimeric mouse-human anti-TNF antibody) and etanercept (a competitive inhibitor of TNF-α to its cell surface receptors) have been tested in AH patients. Both molecules increased mortality due to an increased rate of severe infections. In consequence, biological anti-TNF-α therapies do not have a current role in AH treatment [129,130].

Ineffective liver regeneration has been postulated as one of the potential causes for progressive liver failure in AH [131]. Recently a pilot, open-label, randomized trial comparing granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF) plus standard medical therapy vs. standard medical therapy alone in patients with severe AH showed a significant increase in circulating CD34+ stem cells after G-CSF therapy accompanying a marked decrease in the MELD score and Maddrey's DF at 1, 2, and 3 months of follow-up in the G-CSF group. At 3 months, an improvement in survival was found in the G-CSF compared with standard medical therapy group (78 vs. 30%; P=0.001). Additionally, the development of bacterial infections was less frequent [132]. Oxandrolone (an anabolic-androgenic steroid), propylthiouracil, metadoxine (a drug with antioxidant properties) and other antioxidants such as vitamin E and silymarin have not shown any survival benefit in patients with AH [133–137].

Malnutrition due to impaired caloric intake and increased catabolism is frequent in patients with AH [138]. Two recent, randomized controlled trials evaluating the effect of intensive enteral nutrition have not shown any difference in short-term mortality of patients with severe AH [139,140]. However, patients with low calorie intake (less than 21.5kcal/kg/day) had significantly lower survival at 6 months compared to those with higher calorie intake [140]. Further studies are needed to explore the benefits of nutritional support in this life-threatening condition.

Recently, studies have been carried out evaluating the role of gut microbiota modification in patients with AH. Probiotics have shown to decrease inflammation, improve liver function and decrease re-hospitalizations [141,142]. In another recent pilot study, fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) was associated with lower mortality (as compared with historical controls) in patients with severe AH [143]. There are clinical trials underway examining the role of probiotics, rifaximin and FMT in AH patients.

Artificial and bio-artificial Liver Support Systems, such as the molecular adsorbent recirculating system (MARS) and Prometheus devices, have been tested in patients with ACLF (some of them triggered by superimposed AH). The MARS device, but not the Prometheus device, showed a significant attenuation of hyperdynamic circulation in ACLF, presumably by a difference in the removal rate of certain vasoactive substances [144]. In addition, treatment with MARS also produces an acute reduction on portal pressure and improves encephalopathy in patients with AH [145,146]. However, the effect on relevant clinical outcomes is unknown.

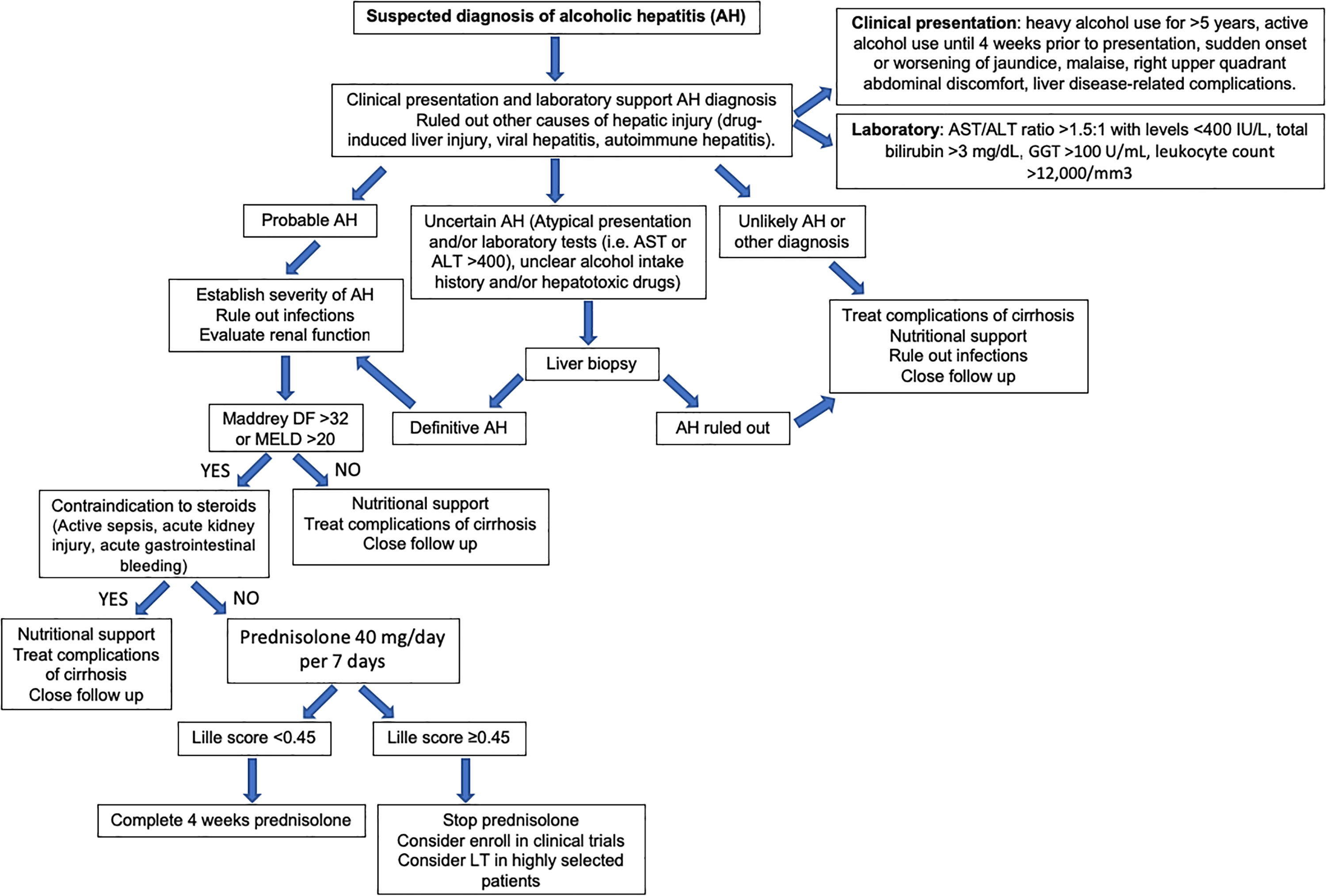

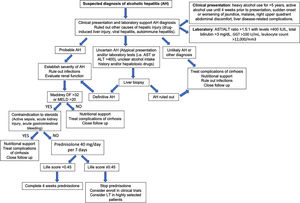

Fig. 6 summarizes a proposed algorithm for the diagnosis and management of AH.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 22.

Corticosteroids are the first-line therapy in patients with severe AH (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong).

- 23.

Pentoxifylline treatment has limited impact improving short and long-term survival of patients with severe AH and is not currently recommended (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong).

- 24.

The use of biological anti- TNF-α drugs has no role in the treatment of severe AH. Their use is not recommended because of their deleterious effects on increasing the rate of severe infections and death in these patients (Grade of evidence: high quality; Grade of recommendation: strong).

- 25.

Antioxidants, such as metadoxine and NAC, may be useful for improving short-term mortality of patients with severe AH receiving corticosteroids (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak).

- 26.

Artificial liver supportive systems do not improve short and long-term survival rates in patients with severe AH (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: strong).

- 27.

G-CSF should not be used outside of clinical studies until further supportive evidence is available (Grade of evidence: low quality; Grade of recommendation: weak).

- 28.

Intensive enteral nutrition in patients with AH has showed no benefit on short-term survival when added to corticosteroid treatment. However, patients with higher calorie intake do have a better survival at 6 months (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 18.

Large clinical trials analyzing the potential benefit of antioxidants in combination with prednisolone on the short and long-term survival of patients with AH.

- 19.

Clinical trials aimed at testing and validating the efficacy of liver regeneration through G-CSF therapy.

- 20.

The potential effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on patient's survival and complication rate should be delineated in future studies.

ALD represents the second most frequent indication for liver transplantation in the United States and Europe. Post-transplant survival of ALD patients is comparable or even higher than that of non-ALD patients [147–149]. There is little information available from Latin-America; however, prospective databases are underway. Studies conducted in some countries of the region show that ALD is among the three leading causes of liver transplant [150–153].

When hepatic function does not improve after sustained alcohol abstinence or when the disease severity does not allow for a prolonged period of abstinence, liver transplant represents a potential curative treatment for patients with life-threatening liver disease related to alcohol [154]. Selection criteria and the minimal duration of abstinence prior to transplantation are a matter of intense debate. In most centers, patients with ALD are required to have a period of abstinence of at least 6 months. This measure is being increasingly questioned especially in patients who do not have other addictions [155,156]. There are no well-conducted studies that support the 6-month abstinence rule as predictor of a lower likelihood of alcohol relapse [156]. Beyond the duration of abstinence, psychosocial factors are likely to be more important as predictors of abstinence after transplantation. Positive predictive factors include self-awareness by the patient of the alcohol problem, the presence of good social support and the attendance to addiction therapy. Negative prognostic factors include the presence of other psychiatric disorders and additional drug abuse, failed previous alcohol therapies and poor family support [157,158]. In a Latin-American study, 16.7% of patients transplanted for ALD had relapse and only 5.6% severe recurrence that led to liver graft dysfunction [153].

In selected patients with severe AH non-responders to medical therapy, recent studies have shown that early liver transplantation (not requiring a minimum period of abstinence) markedly improves survival [159–162]. In these preliminary studies, patients are required to have reasonable family support and absence of other serious psychiatric disorders [163]. Further studies are required to better delineate the indications, patient selection and applicability of early transplant in these patients.

Due to the aforementioned reasons, a comprehensive psychosocial assessment is mandatory in these patients prior to transplantation. In addition, it is important to evaluate other alcohol-induced organ damage including heart failure, chronic pancreatitis, and any involvement of the central and peripheral nervous system [158]. Importantly, since these patients frequently smoke cigarettes and this has been linked to post-transplant cancer and cardiovascular complications, it is highly recommended that patients stop smoking before LT. Attendance to smoking-cessation programs is therefore recommended in this patient population [148,149].

Transplanted patients for ALD have a reduced incidence of acute and chronic rejection compared to patients with nonalcoholic liver disease [164]. In patients transplanted for ALD, the main causes of death are malignancies, infections, and cardiovascular events, mainly related to environmental factors – tobacco, obesity, and alcohol relapse – as well as chronic immunosuppression. Abstinence from cigarette smoking is strongly recommended. As a result, there are current efforts to tailor immunosuppression in patients with ALD by minimizing the exposure to calcineurin inhibitors. Although some recent retrospective studies support this strategy in patients with ALD [165], further studies are needed to define the optimal immunosuppressive regimes in LT recipients due to ALD.

Recommendations/key concepts

- 29.

Liver transplantation should be considered in the management of patients with end-stage ALD (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 30.

In patients with end-stage ALD, candidacy for transplantation criteria should be comprehensive and not only based on the 6-month rule of abstinence, since this may not be feasible in patients with severe AH or severe decompensated ALD where survival is limited (Grade of evidence: moderate quality; Grade of recommendation: weak).

- 31.

Patients undergoing liver transplantation evaluation for ALD should be assessed by multidisciplinary teams, including addiction specialists, and should be screened for use of alcohol and other substances (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

- 32.

Immunosuppression should be prescribed at the lowest possible dose and smoking cessation should be advised and assisted to reduce the risk of cancer in this group of patients. Also, a complete cardiovascular evaluation is advised (Key concept/Expert's opinion).

Suggestions for future studies in Latin-America

- 21.

Epidemiological studies evaluating liver transplantation outcomes for ALD in Latin-America.

- 22.

Studies evaluating criteria and outcomes of patients transplanted for severe AH.

- 23.

Studies on immunosuppression in patients transplanted for ALD.

- 24.

Protocols for cancer and cardiovascular screening in transplanted patients for ALD.