This study aimed to characterize a large cohort of Latinx patients with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and analyze clinical outcomes, including biochemical remission, duration of steroid treatment, fibrosis regression, and incidence of clinical endpoints (hepatic decompensation, need for liver transplant, and death).

Materials and MethodsThis was a retrospective descriptive study of patients with biopsy proven AIH (2009–2019) at a single urban center. Demographics, medical comorbidities, histology, treatment course, biochemical markers, fibrosis using dynamic non-invasive testing (NIT), and clinical outcomes at three months and at one, two, and three years were analyzed.

Results121 adult patients with biopsy-proven AIH were included: 43 Latinx (35.5%) and 78 non-Latinx (65.5%). Latinx patients were more likely to have metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) (p = 0.004), and had higher Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) (p = 0.0279) and AST-to-Platelet-Ratio-Index (APRI) (p = 0.005) at one year. Latinx patients took longer to reach biochemical remission than non-Hispanic Whites (p = 0.031) and longer to stop steroids than non-Hispanic Blacks (p = 0.016). There were no significant differences based on ethnicity in histological fibrosis stage at presentation or incidence of clinical endpoints.

ConclusionsMASLD overlap is highly prevalent in Latinx AIH patients. Longer time to biochemical remission and worse NITs support that this population may have slower fibrosis regression with standard of care AIH treatment. This may indicate differing response rates due to genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism and immune response among Latinx individuals and is less likely related to AIH/MASLD overlap based on the findings of this study.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a chronic liver disease characterized by immune-mediated inflammation and destruction of hepatocytes that typically exhibits elevated levels of autoantibodies, serum immunoglobulins, and transaminases, as well as histological evidence of interface hepatitis, plasma cell rich inflammatory infiltrate, and/or lobular hepatitis [1-4]. Diagnosis is usually made with a combination of clinical findings, biochemical markers, and pathology from liver biopsy [4,5]. While the etiology of AIH remains unknown, it is likely multifactorial and is thought to result from a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers [6,7].

AIH more commonly affects women and can occur at any age and in any ethnicity [6]. While it remains to be determined if AIH is more common in certain racial/ethnic groups in the United States, some studies have found a higher prevalence of AIH in Latinx (of note, Latinx is used in this study as a non-binary, gender-neutral term for Caucasians of Latin American ethnicity often referred to as “Hispanic” or “Latino” in the literature previously) patients compared to other ethnicities [5,8]. Emerging evidence suggests that the Latinx population may exhibit distinct features and clinical presentations of AIH [6]. Given the rapidly growing Latinx population in the United States [9], it will become even more important moving forward to understand this unique patient cohort. So far, studies have suggested that Latinx patients with AIH tend to present at a younger age [10], and present with more advanced liver disease at diagnosis compared to other populations [6,11,12].

Notably little is known about clinical outcomes in the Latinx population with a diagnosis of AIH. In a study of 67 patients with AIH, Lee et al. found no difference in ALT levels at 6 months, time to steroid discontinuation, or liver biopsy inflammation/fibrosis between multiple difference race/ethnicity groups (one of which was Latinx patients) [13]. In a retrospective cohort study of patients at a hospital in Colombia, Diaz-Ramirez et al. noted similar response to treatment to other populations worldwide [14]. Zahiruddin et al. found that in an urban Latino population, a large proportion of patients required continuous prednisone to avoid relapse [12]. Another study found that Hispanics exhibited high rates of hepatic complications from AIH (including ascites, varices, variceal bleeding, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and encephalopathy) [15]. Wen et al. noted that hospitalizations for AIH disproportionately affect Latinx Americans; the rate of hospitalization for AIH was 20% higher in Latinx patients compared to white patients [16]. Existing research is particularly limited by small sample sizes, and in a few studies, a lack of a comparative arm or control group. No studies were found that specifically track outcomes in the Latinx population after 6 months.

Previous data from our study cohort noted a large number of Latinx patients with AIH [4]. Given this and the paucity of existing data with respect to outcomes in this unique population, this study aimed to characterize a large cohort of Latinx patients with biopsy-proven AIH alongside a comparison non-Latinx AIH cohort. It also aimed to analyze clinical characteristics and outcomes at multiple time points of AIH in Latinx patients.

2Material and MethodsThis was a single center, retrospective study. Retrospective chart review was performed of the AIH liver biopsy database (2009–2019) at Rush University Medical Center. The database was searched to identify patients that had AIH on pathology results and followed up with Rush University Medical Center Hepatology Clinic no later than 3 months after liver biopsy. Inclusion criteria included adult (age 18 years or older) patients diagnosed with AIH, supported by standard clinical and laboratory findings and confirmed pathologic findings on liver biopsy consistent with AIH (interface hepatitis, plasma cell infiltration, lobular hepatitis, rosetting). Pathology from liver biopsy was reviewed by one senior liver pathologist who co-reviewed specimens. Histologic findings such as steatosis, lobular inflammation, and/or ballooning were also recorded. Patients were excluded if there was no follow-up for at least 3 months after liver biopsy. For the purposes of this study, the simplified AIH scoring system, developed and published by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) in 2008, was used to make a final diagnosis of AIH (rather than the 1999 original revised scoring system). This system includes and assigns a score to histologic findings, laboratory features (serum IgG), presence of a characteristic autoantibody (antinuclear antibodies [ANA], smooth muscle antibodies [SMA], soluble liver antigen [SLA], and/or liver kidney microsome [anti-LKM1] antibodies), and exclusion of viral hepatitis. Notably, this newer simplified scoring system was tested in patients from Germany, Japan, Spain, Greece, Norway, Brazil, Austria, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and validated in control populations that included a variety of cholestatic, viral, metabolic, toxic and genetic hepatic disorders with a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 97% [17,18]. Notably, it has been validated in the Chilean-Hispanic population, one specific division of Latinx patients [19] It has also been validated in Italian [20], German [21], and Chinese [22] populations. Ultimately, the simplified scoring system is generally universally accepted [18] and was felt to be the most appropriate for use in our population.

Additional data collected included patient demographics, biochemical and immunologic laboratory testing, treatment regimens, and outcomes (mortality, liver transplantation, or cirrhosis decompensation) at 3-month, 1-, 2- and 3-year follow-up. Patients were categorized as either Latinx or non-Latinx based on self-reported data available in the electronic medical record (non-Latinx included non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and “Other”). Median income was estimated using patient zip codes and associated publicly available United States Census data on median family income by zip code [23]. With respect to co-morbidities, hyperlipidemia was defined as significantly elevated LDL (>160 mg/dL) and/or triglycerides (>200 mg/dL) within one year of liver biopsy, or treatment with lipid-lowering therapy at the time of initial hepatology clinic visit. Hypertension was defined as blood pressure greater than or equal to 130/80 in hepatology clinic and/or evidence of treatment with blood pressure lowering medications. Presence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was determined by evidence of hepatic steatosis (>5%) on biopsy or imaging (ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance spectroscopy/imaging, as well as the presence of at least one of five cardiometabolic risk factors: 1) body mass index [BMI] greater than or equal to 24 kg/m2, 2) diabetes mellitus [DM], 3) hypertension [HTN], 4) hypertriglyceridemia, and/or 5) elevated LDL. Alcohol consumption was assessed via available patient-reported social history data in the electronic medical record, collected at the time of initial hepatology clinic visit. Patients with excessive alcohol consumption (weekly or daily) or alternative plausible causes of steatosis (medications, starvation, parenteral nutrition, errors of metabolism) were excluded from the MASLD designation.

Fibrosis stage at biopsy (generally coinciding with the time of AIH diagnosis) was recorded. Fibrosis at future time points was estimated with commonly utilized dynamic non-invasive testing, FIB-4 and APRI; mean FIB-4 and APRI values were calculated at each time point using available laboratory data.

Patients were also classified into treatment categories of standard of care or unconventional management. Standard of care for the purposes of this study was determined by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases [AASLD] 2010 guidelines for AIH management, which recommended prednisone (20–40 mg) followed by azathioprine, or a higher dose (40–60 mg) prednisone monotherapy without azathioprine. Response should be assessed in 4 to 8 weeks, and with good response, gradual tapering of prednisone and attempt at steroid withdrawal is recommended in 3 to 4 months [2]. Notably since this time the AASLD has published updated guidelines (2019) [1], which state that alternatively budesonide (9 mg daily) may be used, but not in cirrhosis or in acute, severe presentation of AIH. 2010 guidelines were used for this study because this was felt to be the most appropriate way to gauge if standard of care at the time of care delivery was followed, given that our study cohort consisted of patients who were seen in clinic between 2019 and 2019 prior to the implementation of the more recent 2019 guidelines.

Biochemical remission was defined per AIH guidelines as normalization of AST, ALT, and IgG levels if available; patients lost to follow up or who reached a clinical endpoint as described below at each time point did not have available data moving forward and were excluded from further analysis. Clinically significant outcomes were defined as coming off steroids (only included if steroids were initiated), achieving biochemical remission, or reaching a “clinical endpoint” of decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, or death.

2a): Statistical Analysis: Continuous measures were compared using t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests when appropriate. Categorical measures were compared using Chi-square tests. Univariate models for FIB-4 and APRI were fit using linear mixed effects models with a Gamma distribution with a log link. These models include a random intercept for patients, and the only fixed effect was time as a categorical variable (initial, 3 months, 1 year, etc.). Multivariable models were fit in a similar manner, but also included sex, comorbidities, diagnosis, and age as fixed effects. Analyses for biochemical remission and off steroids were fit using binary logistic linear mixed effects models with a random intercept for subject and a fixed effect for time. 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. To avoid overlooking important differences within the control group (given that this group included patients of multiple other races and ethnicities), a sensitivity analysis comparing Latinx patients directly to both non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black patients was performed. An “Other race/ethnicity” group included only seven patients and was determined to be too small to perform appropriate sensitivity analysis. Similar statistical analyses were performed using t-tests or Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical measures in the sensitivity analysis. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1.

2b) Ethical Considerations: This study was a non-interventional study and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Rush University Medical Center. Due to the retrospective nature of the study a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) wavier of consent for human subjects was obtained.

3Results121 patients with biopsy proven AIH at onset were included: 43 Latinx (35.5%) and 78 non-Latinx (65.5 %) (Table 1). First, basic demographics were analyzed. There were no significant differences in the gender or age distribution between Latinx and non-Latinx patients (86% vs 82 % female, mean age 51.56 vs 53.29 years respectively). Then, we investigated social determinants of health differences between two groups; there were also no significant differences in median family income based on zip code or insurance type between the Latinx and non-Latinx groups. Latinx patients were, unsurprisingly, less likely to speak English as their primary language (p < 0.001). Of note, one patient did not have a primary preferred language listed in the electronic medical record. Latinx patients had a higher mean baseline body mass index (BMI) (p = 0.029) than non-Latinx patients, but reported significantly less alcohol consumption (p = 0.005). There were also no significant differences in smoking status, the prevalence of additional pre-existing autoimmune disease, or metabolic comorbidities such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus between the two groups.

Demographics.

BMI: Body Mass Index.

USD: United States Dollar.

HTN: Hypertension.

HLD: Hyperlipidemia.

DM: Diabetes mellitus.

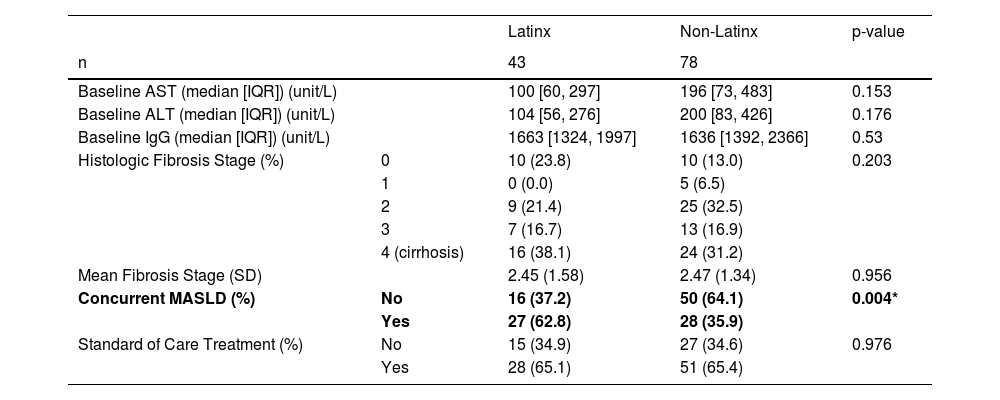

Next, from the clinical perspective, there were no significant differences in median baseline AST, ALT, or immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels between Latinx and non-Latinx patients (Table 2). Notably, Latinx patients were significantly more likely to have a concurrent diagnosis of MASLD (p = 0.004). No significant difference in the histologic stage of fibrosis on biopsy (at diagnosis) was found; notably 16/43 (38.1 %) Latinx versus 24/78 (31.2 %) non-Latinx patients were noted to have cirrhosis at the time of liver biopsy.

Baseline Characteristics & Treatment.

AST: aspartate aminotransferase.

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

IgG: immunoglobulin G.

MASLD: metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease.

With respect to treatment schedule, 28/43 (65.1 % of Latinx patients) received standard of care treatment compared to 51/78 (65.4 %) non-Latinx patients. No significant difference was found in the rate of receiving standard of care treatment between Latinx and non-Latinx patients (p = 0.976).

With respect to outcome data at subsequent time points from onset, there was expected drop off in sample size at each point secondary to patients lost to follow up and/or reaching clinical endpoints (3 months n = 117, 1 year n = 114, 2 years n = 97, 3 years n = 86).

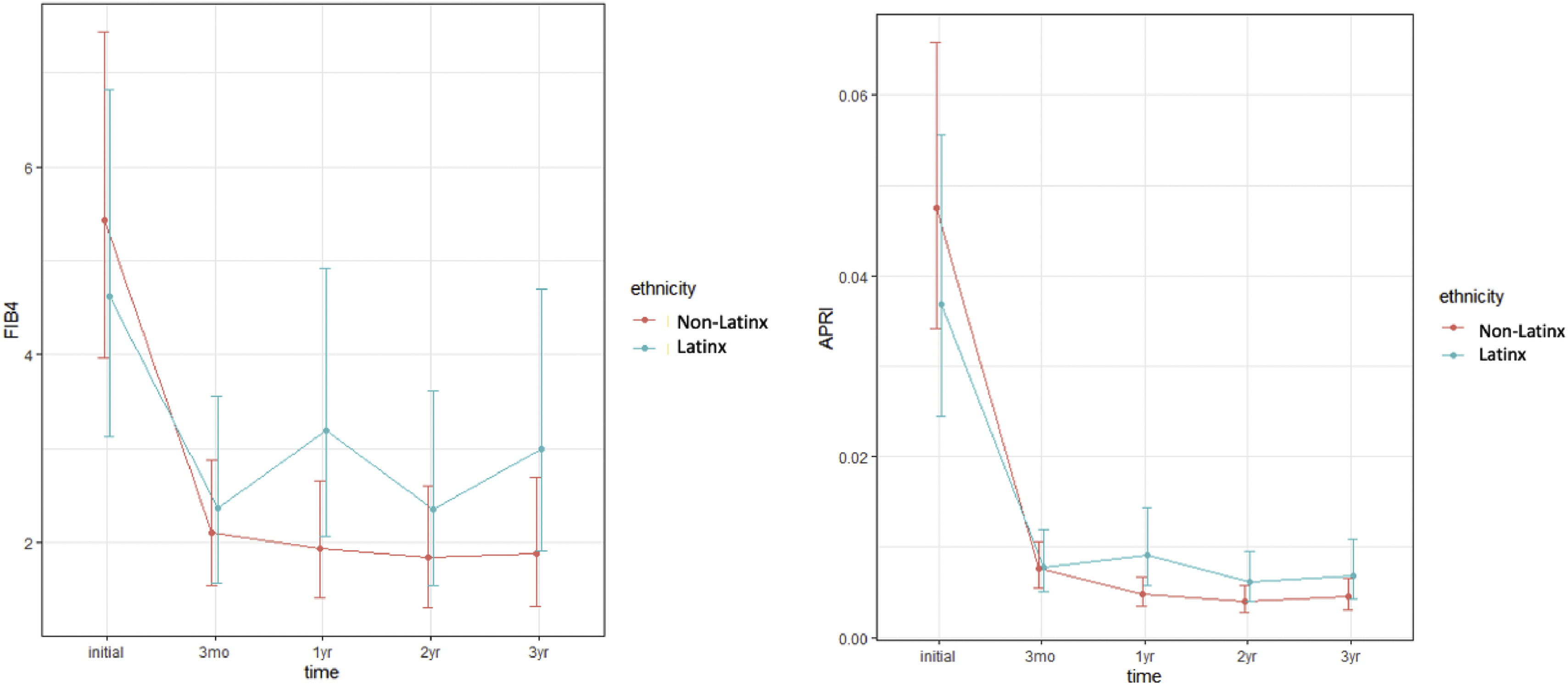

In a univariate analysis, Latinx patients had significantly higher mean APRI at 1 year (p = 0.0116) (Table 3). In a multivariable analysis when controlling for gender, age, BMI, and comorbidities, Latinx patients had both significantly higher mean APRI (p = 0.005) and FIB-4 (p = 0.0279) at one year (Table 4, Fig. 1).

FIB-4 & APRI, Univariate Analysis.

FIB-4: Fibrosis-4.

APRI: AST to Platelet Ratio Index.

FIB-4 & APRI, Multivariate Analysis.

FIB-4: Fibrosis-4.

APRI: AST to Platelet Ratio Index.

Multivariable analysis models of FIB-4 and APRI over time.

Marginal mean estimates and 95% confidence intervals for multivariate models of FIB-4 and APRI showing a trend towards higher FIB-4 and APRI over time in Latinx patients. Although only significant at 1 year (p = 0.0279 and p = 0.005 respectively), it approached significance for each at two and three years as well.

No significant difference in clinically significant outcomes at any time point studied was found between Latinx and non-Latinx patients with AIH (Table 5, Fig. 2). These outcomes included probability of being off steroids if initiated, rates of biochemical remission, and “clinical endpoints” of decompensated cirrhosis, need for liver transplant, or death.

Clinical outcomes (Off steroids, Biochemical remission).

Event free survival probability of reaching a poor clinical endpoint.

Kaplan Meier curves depicting event free survival probability of reaching a poor clinical endpoint of decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, or death; there was no significant difference in clinical endpoints between Latinx and non-Latinx patients (p = 0.64).

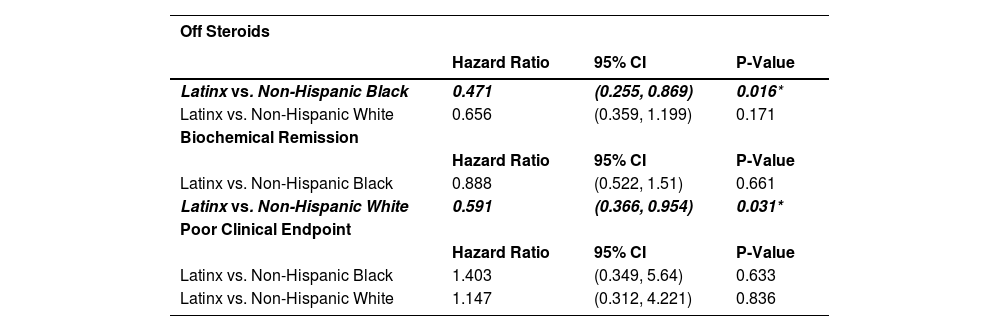

With respect to the sensitivity analysis, when directly comparing Latinx patients (n = 43) to only non-Hispanic White patients (n = 40) with AIH, Latinx patients were more frequently on Medicaid (p = 0.013) and had lower median income based on zip code (p = 0.032). Latinx patients were also significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Black patients (n = 31) to have a concomitant diagnosis of MASLD (p = 0.001) but there was no significant difference between Latinx and non-Hispanic White patients in MASLD prevalence. There were no other new significant differences noted in the sensitivity analysis in gender or age distribution, median family income, insurance type, baseline comorbidities, baseline AST, ALT, and IgG levels, fibrosis stage on biopsy, or in rate of receiving standard of care treatment in the sensitivity analysis. However, Latinx patients took a longer median time to reach biochemical remission (0.96 vs. 0.36 years) and were almost half as likely to be in biochemical remission at any given time than non-Hispanic White patients (HR 0.591, 95% CI (0.366–0.954), p = 0.031) (Fig. 3, Table 6). Latinx patients took a longer median time to come off steroids (2.85 vs. 1.08 years) and about half as likely to be off steroids at any given time than non-Hispanic Black patients (HR 0.471, (95% CI 0.255–0.869), p = 0.016) (Fig. 4, Table 6). Latinx patients had higher FIB-4 (p = 0.045) and APRI (p = 0.012) than non-Hispanic White patients at 1 year, and higher APRI than non-Hispanic Black patients at 1 year (p = 0.012) in a multivariable analysis.

Time to biochemical remission.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to biochemical remission, separated by race/ethnicity .Median time to remission is indicated by the dotted line (Latinx 0.36 years, Non-Hispanic Black 0.36 years, Non-Hispanic White 0.96 years). Latinx patients were overall slower to achieve biochemical remission and notably almost half as likely to be in biochemical remission at any given time than non-Hispanic White patients (HR 0.591, 95% CI (0.366–0.954), p = 0.031).

Sensitivity Analysis – Outcomes.

Time to off steroids.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing time to being off steroids, separated by race/ethnicity. Median time to off steroids is indicated by the dotted line (Latinx 2.85 years, Non-Hispanic Black 1.08 years, Non-Hispanic White 1.18 years). Latinx patients were notably slower to come off steroids and about half as likely to be off steroids at any given time than non-Hispanic Black patients (HR 0.471, (95% CI 0.255–0.869), p = 0.016).

This study found a higher prevalence of MASLD overlap in Latinx patients with AIH compared to non-Latinx patients. This validates previous findings from our initial (smaller) cohort, which found that these overlap patients were more likely to be Latinx [4]. Notably, Latinx patients were found to have higher BMI compared to non-Latinx patients. We suspect that this plays a large role in the higher prevalence of MASLD overlap in this population given that elevated BMI is a known metabolic risk factor for the development of steatosis and MASLD [24]. Specifically, the risk of fatty liver has been found to increase linearly with increasing BMI in a dose-dependent fashion, and those who deposit fat in the abdomen are at higher risk for developing steatosis [25,26].

The etiology behind higher mean BMI in Latinx patients in particular warrants consideration. Obesity is a complex disease that is an outcome of complex interactions between genetic and environmental factors [27]. The Latinx community has been shown to be disproportionately affected by the obesity epidemic [28], the reasons for which are multifactorial. Cultural dietary influences and perceptions likely play a role; for example, traditional Latino diets are high in simple carbohydrates than white and African-American diets, which can promote obesity [29]. Previous studies have also found that Latinx community is on average less concerned than whites about being overweight [30] and less understanding of the health consequences of obesity [30,31]. Additionally, socioeconomic factors such as a lack of transportation or access to grocery stores, less leisure time secondary to long work hours or lack of child care, and/or simply inability to afford fresh, healthier foods are more prevalent in the United States Latinx population [32]. Genetics often play a role as well; specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the TUB gene that predispose to obesity have been identified in the Latinx population [33]. Specifically with respect to hepatic steatosis, Latinx patients have an increased prevalence of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 (PNPLA3) polymorphisms which is known to cause worse steatosis and is associated with high rates of MASLD [34-36].

Interestingly, Latinx patients appeared to consume alcohol less frequently (although this data was self-reported and did not quantify alcohol consumption) than non-Latnix patients, even in the setting of higher MASLD prevalence. As we excluded patients with reported daily and weekly alcohol use from the MASLD designation, we do not expect that the difference in alcohol intake between the groups had a major impact on the study. However, given the steatotic effects of alcohol on the liver, we suspect that if anything the prevalence of MASLD may be over-estimated in the non-Latnix group and the true difference in MASLD prevalence may actually be even higher than reported.

With respect to clinical outcomes, we found that Latinx patients appear to take longer to achieve biochemical remission compared to non-Latinx White patients. This contrasts with what was previously found in the Lee et al. study, where there were no significant differences in ALT levels at 6 months between multiple difference race/ethnicity groups (including Latinx patients) [13]; however, our study has the advantage of data collected for a longer time period after AIH diagnosis compared to Lee et al. We suspect that longer time to biochemical remission is likely at least in part related to the higher prevalence of MASLD overlap in Latinx patients. In our initial smaller cohort, we similarly found slower time to biochemical remission in overlap patients at one year, supporting the sentiment that the presence of MASLD may be a contributory factor to slowed remission [4]. As steroids (included in standard of care treatment for AIH) have the potential to worsen steatosis, it has also notably been proposed that the metabolic side effects of steroids may worsen underlying outcomes in MASLD [4]. While the 2019 AASLD guidelines were updated to mention that concurrent fatty liver disease may influence response to therapy, still no clear recommendations exist regarding optimization of AIH treatment when MASLD overlap is present. Given this, we feel that patients with AIH/MASLD overlap may benefit from an alternative definition of biochemical remission, but further research is needed as to how this should be approached. This is particularly applicable to the Latinx AIH population in which we have found such a high prevalence of AIH/MASLD overlap.

While some previous studies have suggested that Latinx patients may be more likely to present with cirrhosis [6,11,12], we interestingly found no significant difference in the level of fibrosis on initial biopsy between Latinx and non-Latinx patients. However, higher APRI and FIB-4 at one year, despite no differences in duration of steroid treatment or in rates of receiving standard of care treatment (again compared to non-Hispanic Whites) indicate that the Latinx AIH population may have slower fibrosis regression with AIH treatment and suggests to us that there may be more nuanced underlying differences in disease progression that we are missing in this population. Interestingly, this difference in fibrosis regression was only statistically significant at one year. We suspect that this may be related to decreasing sample size and thus lower statistical power at each time point in the setting of loss to follow up and clinical endpoints.

If it is true that Latinx patients have slower fibrosis regression, we propose that this may be due to genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism and immune response among Latinx individuals. Potential behavioral and socioeconomic contributions, such as sub-optimal patient-provider communication in the setting of a language barrier, medication non-compliance, and/or issues affording medications, should also not be ignored. A possible association between underlying MASLD and progression of fibrosis in AIH has also been previously suggested [8]; however in our previous cohort of AIH/MASLD overlap patients, no evidence of fibrosis progression was found (based on lack of difference in non-invasive fibrosis scores and clinical outcomes over time) [37]. Similarly, Lee et al. was unable to find a significant contribution from steatohepatitis to AIH fibrosis in their cohort of Latinx patients [38], and Chalasani et al. found that while steatosis is highly prevalent in AIH patients, it is not associated with fibrosis [3409]. Additionally, while Mederacke et al. found that the PNPLA3-rs738409 GG variant was a predictor of liver transplant or mortality in AIH patients, they found no association between hepatic steatosis and cumulative survival (presumed in part related to a possible lack of worse fibrosis) [39]. These findings together support the notion that there may be no significant contribution from MASLD to fibrosis progression in the AIH/MASLD overlap population. As such, we favor previously described potential genetic, behavioral, and socioeconomic etiologies as more prevalent mechanisms in slower fibrosis regression.

Ultimately and perhaps most importantly, our study found no significant differences in clinical endpoints (decompensated cirrhosis, liver transplant, or death) between Latinx and non-Latinx AIH patients; we believe we are the first study to evaluate these clinical endpoints in the Latinx AIH population. Wen et al. did note in a retrospective study that hospitalizations for AIH disproportionately affect Latinx Americans; the rate of hospitalization for AIH was 20% higher in Latinx patients compared to white patients [16]. We did directly not evaluate the frequency of hospitalization in our Latinx population but consider the presence of decompensated cirrhosis to be a reasonable surrogate for a common reason for hospitalization in this population. Future studies would benefit from including hospitalization rates as another measure to pick up on more nuanced differences in outcomes. We also believe that this is the first study to specifically characterize and compare outcomes between Latinx AIH patients and other race/ethnicities over time as far out as three years. Future studies may benefit from following patients for even longer, as it is possible that three years may not be long enough to appreciate true differences in clinical endpoints.

This study has a few additional important limitations. First, while our sample size was larger than many previous similar studies, it may be considered small with respect to making epidemiological conclusions and having a true impact on clinical practice. Additionally, as a retrospective cohort study, there is certainly potential for selection bias. In our study, lab values and outcomes for patients lost to follow up were included up until they were no longer available in the EMR. For example, if the patient was lost to follow up after the 2-year mark, their data was not included for the 3-year mark. Given this, it is possible that worse outcomes that were not captured as a result. As such, our sample size at each time point notably decreased based on those lost to follow up (as well secondary to mortality, although this was overall minimal in our population for the time points studied). It is also important to acknowledge that patients lost to follow up also may have unique socioeconomic risk factors that pre-dispose them to worse healthcare outcomes in general.

There was also potential for information bias given the retrospective nature of the study; it is possible that information in the EMR may not have been completely accurate, and this should be considered. Additionally as a single-center study, the study population is representative of one location and may not be representative of Latinx populations elsewhere in the United States and/or worldwide. It is important to acknowledge that the Latinx population is also inherently diverse itself and includes people from a wide range of backgrounds and nations, including but not limited to Mexico, Central America, South America, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Spain [7]. Genetic predisposition to AIH has been shown to be linked to genes within the major histocompatibility complex human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region, and the distribution of different HLA alleles varies across different parts of Latin America and Europe [7]. For example, Muratori et al. found that HLA DR4 and B8-DR3-DQ2 were more frequent in North American patients compared to Italian patients with type 1 AIH [40]. This increased genetic predisposition to AIH in North American patients may also play a role in the increased prevalence of AIH/MASLD overlap in our North American Latinx population. Our study is not able to comment on the backgrounds of our Latinx AIH population as this data was not readily available as part of routine clinical care.

It is also important to understand the current limitations of using FIB-4 and APRI in predicting fibrosis in AIH. Notably, in a systematic review of 16 studies, Wu et al. found that FIB-4 and APRI have a poor positive predictive value for staging of liver fibrosis in AIH [41]. For this reason, we chose to not evaluate baseline FIB-4 and APRI. However, as the Wu et al. study looked at the diagnostic accuracy of FIB-4 and APRI within seven days of liver biopsy in most studies, few conclusions can be drawn about the value of using these non-invasive fibrosis scores at future time points. Given the limited options that currently exist for assessing fibrosis over time in AIH, we chose to analyze FIB-4 and APRI at follow-up and advise caution in interpretation of these values. Along these lines, while not possible in our case given the retrospective nature of our study, future prospective studies would benefit from using more validated methods for evaluating fibrosis at follow-up time points. One promising example is transient elastography (Fibroscan), which has been shown to perform better than non-invasive markers such as FIB-4 and APRI in assessing fibrosis in AIH [41,42]. Of note, FIB-4 and APRI have showed good accuracy in advanced fibrosis detection in MASLD [43–45], for which fibrosis is often both pericellular and portal [45], compared to the more characteristic portal fibrosis of AIH [46].

In summary, understanding the unique aspects of AIH in racial and ethnic minorities remains crucial for accurate diagnosis, optimal management, and improved patient outcomes. Specifically, the Latinx population in the United States grew 23% from 2010 to 2020 [9]; with continued growth, it will be increasingly important to understand the differences in characteristics and outcomes to ultimately improve AIH management in this unique cohort. Further research is needed to understand the exact mechanisms at play in AIH within the Latinx population as there are likely specific genetic, socioeconomic, and lifestyle-related factors that have impact on the clinical course of the disease in this population.

5ConclusionsLatinx patients appear overall more likely to have AIH/MASLD overlap, and also seem to have, on average, slower achievement of biochemical remission and slower fibrosis regression with existing “standard of care” AIH treatment compared to non-Hispanic White patients. However, there appears to be no significant contribution from MASLD to the progression of fibrosis in AIH.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributionsEleanor Belilos - Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Project administration; Jessica Strzepka - Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - review & editing; Ethan Ritz - Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing - review & editing; Nancy Reau - Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing; Costica Aloman - Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Project administration.

Data availability statementThe data behind this research project is readily available can be accessed at the request of the reader.

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Rush University Medical Center. A HIPPA wavier of consent was obtained due to the retrospective nature of the study – researchers had no direct contact with human subjects.