Epidemiological and clinical studies have found that gallstone prevalence is twice as high in women as in men at all ages in every population studied. Hormonal changes occurring during pregnancy put women at higher risk. The incidence rates of biliary sludge (a precursor to gallstones) and gallstones are up to 30 and 12%, respectively, during pregnancy and postpartum, and 1-3% of pregnant women undergo cholecystectomy due to clinical symptoms or complications within the first year postpartum. Increased estrogen levels during pregnancy induce significant metabolic changes in the hepatobiliary system, including the formation of cholesterol-supersaturated bile and sluggish gallbladder motility, two factors enhancing cholelithogenesis. The therapeutic approaches are conservative during pregnancy because of the controversial frequency of biliary disorders. In the majority of pregnant women, biliary sludge and gallstones tend to dissolve spontaneously after parturition. In some situations, however, the conditions persist and require costly therapeutic interventions. When necessary, invasive procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy are relatively well tolerated, preferably during the second trimester of pregnancy or postpartum. Although laparoscopic operation is recommended for its safety, the use of drugs such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and the novel lipid-lowering compound, ezetimibe would also be considered. In this paper, we systematically review the incidence and natural history of pregnancy-related biliary sludge and gallstone formation and carefully discuss the molecular mechanisms underlying the lithogenic effect of estrogen on gallstone formation during pregnancy. We also summarize recent progress in the necessary strategies recommended for the prevention and the treatment of gallstones in pregnant women.

Epidemiological and clinical studies showed that at all ages, women are twice as likely as men to form cholesterol gallstones. This gender difference begins since puberty and continues through the childbearing years. Most, but not all, studies have found that the risk of developing cholesterol gallstones is markedly increased by oral contraceptive steroids and conjugated estrogens in premenopausal women.1–7 Estrogen therapy to postmenopausal women and to men with prostatic carcinoma also induces similar lithogenic effects.8–13 These findings underscore the importance of female sex hormones on the pathogenesis of gallstones. Furthermore, hormonal changes that occur during pregnancy put women at even higher risk for gallstone formation.14–17 Biliary cholesterol concentrations in gallbladder bile increase gradually from the first to the third trimester of pregnancy, along with a progressive increase in the incidence of biliary sludge (a precursor to gallstones) and gallstones.18–20 Clinical studies in the USA and Europe have found that the incidence rates of biliary sludge and gallstones are up to 30 and 12%, respectively, during pregnancy and postpartum.20–28 Although most women remain asymptomatic, 1-3% of pregnant women undergo cholecystectomy due to clinical symptoms or complications within the first year postpartum.20–28 Because more than 4 million women give birth annually in the USA, it is estimated that at least 40,000 young healthy women require postpartum cholecystectomy each year. Thus, pregnancy-associated gallbladder disease is a significant cause of morbidity in young healthy women.

Parity and length of the fertility period increase the incidence of gallstones,29 as well as both the frequency and number of pregnancy are important risk factors for gallstone formation.14,16,30–34 Of note, gallbladder disease is the most common non-obstetrical cause of maternal hospitalization in the first year postpartum,35,36 with 30% attacks of biliary colic in women with gallstones.23 Following acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis is the second most common indication for non-obstetric surgery in pregnant women.37 Again, it indicates that gallbladder disease is a significant cause of morbidity for pregnant women.27 Although pregnancy constitutes a defined period of metabolic stress, a subclinical trend to form gallstones clearly exists.27 Pregnant women with gestational diabetes or high blood pressure are at risk of later developing diabetes mellitus or hypertension.38,39 A similar phenomenon could happen with biliary sludge and gallstones. Thus, elevated estrogen levels are a critical risk factor for developing gallbladder disease during pregnancy. Moreover, biliary sludge and gallstones can spontaneously disappear after parturition in approximately 60% of cases mostly due to a sharp decrement in estrogen levels.20 It is important in clinical practice, therefore, to find a way to reduce the risk of cholelithiasis in pregnant women.

Human and animal studies have found that estrogen increases susceptibility to cholesterol cholelithiasis by promoting hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol,18,19,40–47 enhancing bile lithogenicity and impairing gallbladder motility function.10,48,49 Such alterations, in turn, lead to a dramatic increase in cholesterol saturation of bile and gallbladder stasis, thereby enhancing cholelithogenesis.1,50–52 We have found that the hepatic estrogen receptor α (ERa), but not ERβ, plays a major role in cholesterol gallstone formation in mice exposed to high doses of 17β-estradiol.53 A novel concept has been proposed that high levels of estrogen promote the formation of cholesterol gallstones through the ERa signaling cascade in the liver and higher risks for gallstone formation in women than in men are related to differences in how the liver handles cholesterol in response to estrogen.54

In this paper, we systematically review the incidence and natural history of pregnancy-related biliary sludge and gallstones and carefully discuss the molecular mechanisms underlying the lithogenic effect of estrogen on gallstone formation during pregnancy. We also summarize recent advances in the prevention and the treatment of cholesterol gallstones in pregnant women.

Changes in Plasma Estrogen Levels During the Menstrual Cycle and During PregnancyThe menstrual cycle is essential for the production of eggs and for the preparation of the uterus for pregnancy.55 It consists of:

- •

The ovarian cycle that describes changes in the follicles of the ovary and

- •

The uterine cycle that outlines changes in the endometrial lining of the uterus.

Both the ovarian and the uterine cycles are divided into three phases. The ovarian cycle is composed of:

- •

Follicular phase,

- •

Ovulation, and

- •

Luteal phase.

Whereas the uterine cycle is divided into:

- •

Menstruation,

- •

Proliferative phase, and

- •

Secretory phase.56

The stages of the menstrual cycle are characterized by fluctuations of the four major circulating hormones: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol and progesterone.57,58 Although plasma concentrations of these hormones vary substantially on an hourly basis, their daily profiles provide characteristic changes during the menstrual cycle.57 The follicular phase is defined by a preovulatory estrogen peak in the absence of progesterone.8

During the luteal phase, following ovulation, a simultaneous increase of both estradiol and progesterone occurs.56,58–60

Plasma concentrations of unconjugated estrone (E1), estradiol (E2) and estriol (E3) increase steadily as pregnancy progresses.3,4,19 Estradiol levels in plasma are the highest, followed by estriol and estrone. Only during pregnancy, fetal liver produces some amounts of estetrol (E4); however, its plasma concentration is still very low in pregnant women.4,20 In pregnant women, plasma estradiol concentrations range from 6 to 30 ng/mL.3,29 At 9 weeks of pregnancy, i.e., 23% of gestational length, the placenta becomes the primary source of estrogen.61 In the late stage of pregnancy, plasma concentrations of estradiol and estrone are approximately 100-fold higher than the respective average values in the menstrual cycle.4,23 These alterations greatly enhance susceptibility to cholesterol gallstones in pregnant women.

Gallstone Prevalence in Pregnant WomenDuring pregnancy, elevated estrogen levels are often associated with a significant increase in hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol. As a result, bile becomes supersaturated with cholesterol and is more lithogenic. Additionally, high levels of estrogen and progesterone could impair gallbladder motility function by inhibiting gallbladder smooth muscle contractile function, thus leading to gallbladder stasis.10,49 Such abnormalities greatly promote the formation of biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnant women. The incidence of disease appears to be increased in the last two trimesters of pregnancy. However, approximately one third of pregnant women with gallstones is asymptomatic.21,23,24 When symptoms do occur in pregnant women, however, the most common clinical presentations are biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, and jaundice.62

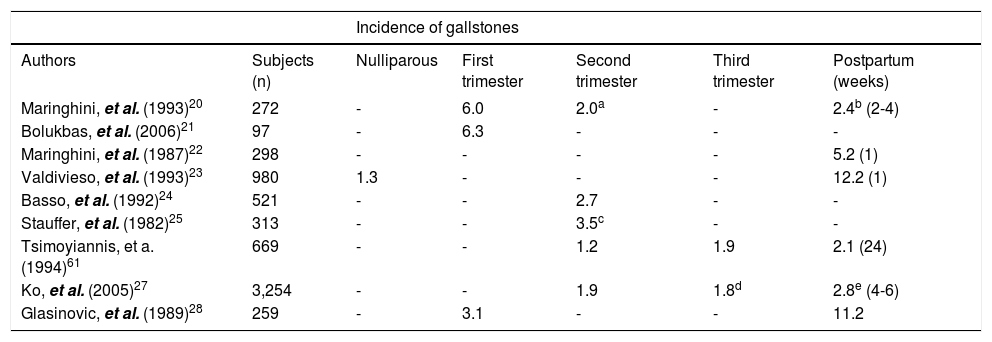

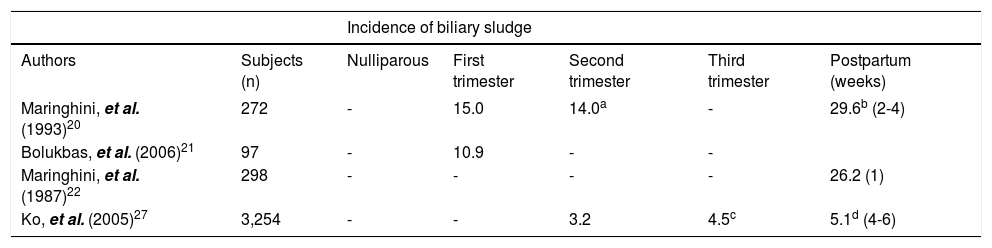

As listed in table 1, the incidence rates of gallstones range from 1.2 to 6.3% during pregnancy.21–25 Since the concentration of plasma female sex hormones increases proportionally with duration of gestation, the risk of gallstone formation is especially hazardous in the third trimester of pregnancy. Furthermore, increasing parity could be a significant risk factor for gallstones, especially in younger women.61,63,64 Clinical studies have observed that approximately 5.1% of women developed gallbladder disease after one pregnancy, 7.6% after two pregnancies, and 12.3% after 3 or more pregnancies.14,27,30–32 A study in Chile reported that the incidence of gallstones was 12.2% of multiparous women compared to 1.3% of nulliparous women within the same age.65 Another study has reported that women under the age of 25 years with ≥ 4 pregnancies were 4 to 12 times more likely to develop cholesterol gallstones compared to nulliparous women of the same age and body weight.66

Gallstones formation during pregnancy and after delivery.

| Incidence of gallstones | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Subjects (n) | Nulliparous | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | Postpartum (weeks) |

| Maringhini, et al. (1993)20 | 272 | - | 6.0 | 2.0a | - | 2.4b (2-4) |

| Bolukbas, et al. (2006)21 | 97 | - | 6.3 | - | - | - |

| Maringhini, et al. (1987)22 | 298 | - | - | - | - | 5.2 (1) |

| Valdivieso, et al. (1993)23 | 980 | 1.3 | - | - | - | 12.2 (1) |

| Basso, et al. (1992)24 | 521 | - | - | 2.7 | - | - |

| Stauffer, et al. (1982)25 | 313 | - | - | 3.5c | - | - |

| Tsimoyiannis, et a. (1994)61 | 669 | - | - | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.1 (24) |

| Ko, et al. (2005)27 | 3,254 | - | - | 1.9 | 1.8d | 2.8e (4-6) |

| Glasinovic, et al. (1989)28 | 259 | - | 3.1 | - | - | 11.2 |

It has been shown that the prevalence of gallstones in women who had two to three or more pregnancies was 2- to 3-fold higher compared with nulliparous women.67 In the Italian GREPCO study, the prevalence of gallstones positively correlated with the number of pregnancies and age.68 The frequency appears to increase after two, three or more pregnancies, and this trend was more marked in younger women at the ages of 25 to 30 years vs. 35 to 40 years.61,64 Several population studies attempted to quantify the risk of gallstones caused by multiple pregnancies, adjusting for at least some known confounding factors. However, the number of multiple pregnancies and the adjustment for confounding factors were not uniform. The results from the Sirmi- one study,14 the Framingham study16 and the MICOL study69 were surprisingly similar, and the relative risks were 1.7, 1.6 and 1.7, respectively. These and other studies provided definitive evidence that multiple pregnancies are a critical risk factor for the development of gallstones.

Biliary sludge in pregnancy is attributed to two major mechanisms: estrogen-induced metabolic abnormalities in the formation of lithogenic bile and progesterone-induced smooth muscle relaxation with subsequent gallbladder hypomotility.51,52,70–72 As shown in tables 1 and 2, the frequency of biliary sludge has been observed to be higher than that of gallstones (~15.0% vs. ~6.0%) during pregnancy.23,73 Although not all cases of biliary sludge evolve to gallstones, the presence of sludge is a necessary precursor involved in the formation of gallstones.27,51,52,74 Clinical studies have reported that biliary sludge can spontaneously disappear and recur over time, or it can proceed to gallstones. Biliary sludge is mostly asymptomatic and disappears when the primary condition resolves; however, in some cases it can progress into gallstones or migrate to the biliary tract, occluding the cystic duct or the common bile duct and causing biliary colic, cholangitis or pancreatitis. It should be noted that biliary sludge in the majority of women usually disappears a few weeks after the pregnancy concludes/ terminates/ends.66 However, only a fraction of pregnant women with sludge develop gallstones.72 Gallstones and biliary sludge can spontaneously resolve in most women during the first year after delivery. However, it is considered that women with multiple or closely spaced pregnancies may form gallstones as sludge recurs or persists.75

Biliary sludge formation during pregnancy and after delivery.

| Incidence of biliary sludge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Subjects (n) | Nulliparous | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | Postpartum (weeks) |

| Maringhini, et al. (1993)20 | 272 | - | 15.0 | 14.0a | - | 29.6b (2-4) |

| Bolukbas, et al. (2006)21 | 97 | - | 10.9 | - | - | |

| Maringhini, et al. (1987)22 | 298 | - | - | - | - | 26.2 (1) |

| Ko, et al. (2005)27 | 3,254 | - | - | 3.2 | 4.5c | 5.1d (4-6) |

Based on ultrasonographic assessment of the gallbladder in 298 women in the immediate postpartum period, the incidence of biliary sludge was found to be 26.2% and the incidence of gallstones was 5.2%. After 1 year of follow-up, only 2 out of 45 patients with biliary sludge, but 13 out of 15 patients with gallstones still had abnormal ultrasonographic findings.22 In another report, the prevalence of biliary sludge in pregnant women ranged from 5 to 36% and the prevalence of gallstones from 2 to 11%.63 A prospective study of 272 women recruited in the first trimester of pregnancy and followed for almost one year postpartum found that new biliary sludge developed in 67 women and gallstones in 6 women in pregnancy. Whereas, women with biliary sludge remained generally asymptomatic, 28% of women with gallstones developed biliary pain during pregnancy. About half of the study population (115 women) was reexamined in the postpartum period. Of these, 92 had biliary sludge and 23 had gallstones. Biliary sludge disappeared in 56 affected women (61%) and gallstones were dissolved in 6 women (28%) by several months post-partum.20

It has been observed that over a 7- to 8-month period from the first trimester to the early postpartum, the cumulative incidence of biliary sludge was 5%, whereas an additional 5% developed incident gallstones or progressed from baseline sludge to gallstones. Overall, 4.2% of women had newly formed biliary sludge or gallstones that were found by ultrasonography in the early postpartum.27 Several groups performed abdominal ultrasound examinations in women in the immediate postpartum period comparing the same examinations performed in the same women at the beginning of pregnancy or in age matched nulliparous women. In two large Chilean studies, approximately 12.2% of women were found to have gallstones in the postpartum period compared with 3.1% in the same women at the beginning of pregnancy and 1.3% in nulliparous women.23,72

When gallbladder motility is restored in the post-partum period, biliary sludge and gallstones could pass into the cystic duct or the common bile duct, and this is a condition at risk of biliary colic or other complications such as obstructive jaundice or pancreatitis. Alternatively, because of a sharp reduction in estrogen concentrations after childbirth, postpartum changes in lipid composition of bile could favor dissolution of biliary sludge and gallstones. Maringhini, et al. reported that both biliary sludge and gallstones disappeared in 61 and 28%, respectively, during the first year after delivery.20 This suggests that pregnancy-associated biliary lithogenicity and gallbladder hypomotility may be a crucial factor in the formation of biliary sludge and gallstones during gestation.51

Ko, et al. evaluated the incidence and natural history of pregnancy-related biliary sludge and gallstones and reported an incidence of biliary sludge or gallstones of 5.1% by the second trimester, 7.9% by the third trimester, and 10.2% by 4 to 6 weeks post-partum.27 Twenty-eight women (0.8%) underwent cholecystectomy within the first year postpartum.27

Biliary diseases at delivery or hospitalization within 1 year postpartum were documented in approximately 0.5% of all births in Washington State between 1987 and 2001, with cholecystectomy performed within 1 year postpartum for approximately 0.4% of births during this time period. A population-based study found that 2.1% of women aged 20-29 year and 4.9% of women aged 30-39 year have undergone cholecystectomy.30,35 Because many of these women would have undergone cholecystectomy in the first postpartum year, these findings suggest that the postpartum period is a time of high risk for symptomatic gallstone disease requiring further treatment. Notably, hospitalizations resulting from gallstone-related disease in the first year postpartum period incur median charges of $5,759 in the mid-1990s, with a median length of stay of 3 days.35

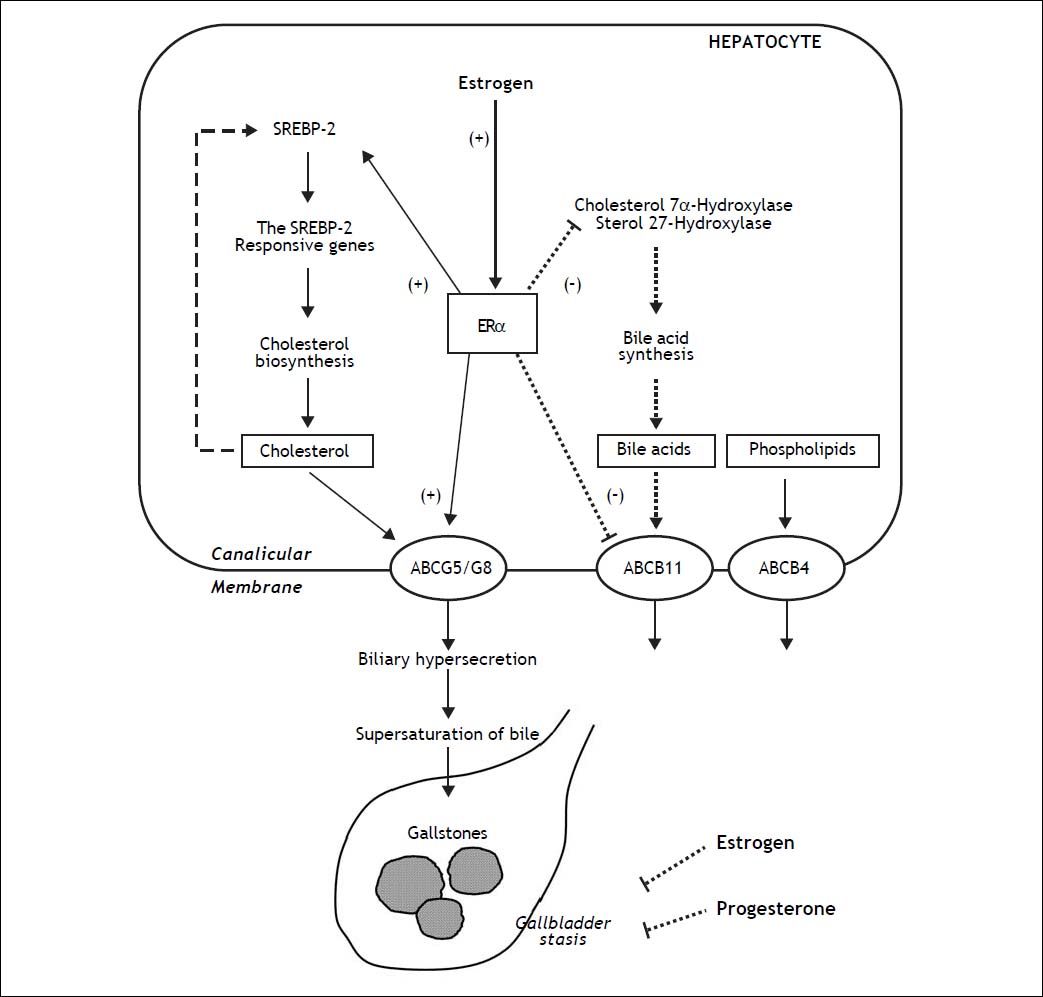

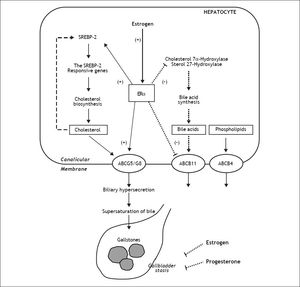

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Lithogenic Effect of Estrogen on the Formation of Cholesterol Gallstones in Pregnant WomenPregnancy and parity are two important risk factors for the formation of cholesterol gallstones in women.23,29,31,62,76 As shown in figure 1, increased levels of female sex hormones during pregnancy induce a variety of metabolic changes in the hepatobiliary system, which ultimately cause bile to become supersaturated with cholesterol and enhance cholelithogenesis.10 Moreover, biliary lithogenicity occurs as a result of estrogen-induced increase in cholesterol biosynthesis, providing excess amounts of cholesterol for biliary hypersecretion during pregnancy.10 So, cholesterol saturation index of bile increases especially during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. The secretion rate of cholesterol relative to that of bile acids and phospholipids is increased markedly.77 Moreover, hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol has been found to be increased by 40% in nonpregnant women treated with estrogen.8 In addition, the gallbladder becomes sluggish and enlarged and empties incompletely, which further increases the risk of gallstone formation.77

The proposed working model underlying the potential lithogenic mechanisms of estrogen through the estrogen receptor a (ERα) pathway in the liver during pregnancy. In the liver, there is an “estrogen-ERα-SREBP-2” pathway promoting cholesterol biosynthesis and hepatic hypersecretion of biliary cholesterol in response to estrogen. The negative feedback regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis (as shown in a dashed line) is inhibited by ERα that is activated by estrogen, mostly through stimulating the activity of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2 (SREBP-2) with the resulting activation of the SREBP-2 responsive genes for the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway. Consequently, these alterations induce excess secretion of newly synthesized cholesterol and supersaturation of bile that predisposes to cholesterol precipitation and gallstone formation. By contrast, estrogen could reduce bile acid biosynthesis by inhibiting cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase in the classical pathway and sterol 27-hydroxylase in the alternative pathway through the ERa signaling cascade (as shown in a dotted line). Moreover, the hepatic ERα activated by estrogen could stimulate the activity of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters ABCG5/G8 on the canalicular membrane of the hepatocyte and promote biliary cholesterol hypersecretion. It is likely that expression levels of ABCB11 are inhibited by estrogen through the ERα pathway, inducing biliary bile acid hyposecretion (as shown in a dotted line). In addition, high levels of estrogen and progesterone induce smooth muscle relaxation with subsequent impaired gallbladder motility function, leading to gallbladder stasis (as shown in dotted lines). All of these alterations promote the formation of biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnant women exposed to high levels of estrogen.10

Estrogen could promote cholesterol cholelithogenesis by enhancing functions of estrogen receptors in the liver and gallbladder.54 ERa and ERβ are both expressed in the hepatocytes although they have overlapping but not identical tissue expression patterns.53,78–80 However, gene expression levels of ERa are ~50-fold higher compared with ERβ. These findings imply that ERa is a major steroid hormone receptor producing the biological effects of estrogen in the liver.10 We investigated the molecular mechanisms of how estrogen influences cholesterol gallstones formation in a mouse model of gonadectomized gallstone-resistant AKR mice.53 Expression levels of ERa were significantly increased after its activation by 17β-estradiol (E2), the ERa-selective agonist propylpyrazole (PPT), and tamoxifen. However, the E2 effects on expression of the hepatic ERa mRNA was blocked by the antiestrogenic ICI 182,780. The ERβ-selective agonist diarylpropionitrile (DPN) did not influence gene expression of ERa, but up-regulates the expression of ERβ in the liver.53 Although the prevalence of gallstones displayed a dose-dependent increase in gonadectomized mice treated with various doses of exogenous E2, all mice treated with E2 at 6 µg/day plus ICI 182,780 were gallstones free. These findings indicate that the lithogenic effects of E2 are blocked by this antiestrogenic agent. Moreover, 75% of the mice treated with PPT formed gallstones, suggesting its strong lithogenic effect. Tamoxifen promoted gallstone formation with a prevalence rate of 50%, indicating its estrogen-like effects on biliary lipid metabolism. By contrast, DPN did not influence gallstone formation. Thus, the receptor-dependent effects of E2 contribute to biliary cholesterol hypersecretion and lithogenicity of bile, promoting gallstone formation through the hepatic ERα, but not ERβ pathway.

One mechanism of estrogen-mediated hepatic secretion of biliary cholesterol is that the activity of 3- hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis, is enhanced, followed by increased delivery of cholesterol from hepatic de novo synthesis to bile.1,53,81–83 Estrogen could increase the capacity of dietary cholesterol to induce cholesterol supersaturation of bile.1,53,81,82,84 To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which E2 increases hepatic output of biliary cholesterol, we quantitated the contribution of newly synthesized cholesterol to biliary output in gonadectomized AKR mouse treated with high doses of estrogen and fed a high-cholesterol diet.83 Compared with control mice (i.e., female AKR mice with intact ovaries), E2-treated mice with gonadectomy displayed a significantly higher hepatic output of biliary total and newly synthesized cholesterol, regardless of whether chow or the high-cholesterol diet was fed. These biological effects of E2 were abolished by ICI 182,780. Thus, the origin of biliary cholesterol possibly comes mostly from the high cholesterol diet and partly from lipoproteins such as HDL carrying cholesterol from extrahepatic tissues via a reverse cholesterol transport pathway. To regulate the hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis, E2could activate ERα which, in turn stimulates mRNA expression of sterol regulatory element binding proteins-2 (SREBP-2) and five major SREBP-2-responsive genes (HMG-CoA synthase, HMG-CoA reductase, farnesyl diphosphate synthase, squalene synthase, and lathosterol synthase) in the liver.83 Compared to the chow diet in control mice, expression levels of SREBP-2 were significantly reduced by the high dietary cholesterol. These findings suggest that cholesterol biosynthesis may be inhibited by a negative feedback regulation through the SREBP-2 pathway in response to high dietary cholesterol. By contrast, E2-treated mice still showed significantly higher expression levels of SREBP-2 and the SREBP-2-responsive genes, even under high dietary cholesterol loads. These results indicate that with high levels of E2, there is a continuous cholesterol synthesis in the liver because the negative feedback regulation of its synthesis by the SREBP-2 pathway may be inhibited by E2 through the hepatic ERa. Likely, under the normal physiological conditions, there is a negative feedback regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis by cholesterol. With increased E2 levels, however, there is a possible “estrogen-ERα-SREBP-2” pathway for the regulation of hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis. This suggests a loss in the negative feedback regulation of cholesterol biosynthesis, which, in turn, results in hepatic secretion of excess amounts of newly synthesized cholesterol and supersaturation of bile that predisposes to the precipitation of solid cholesterol crystals and the formation of gallstones.

It is well known that progesterone is a potent inhibitor of hepatic acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT), thereby decreasing hepatic synthesis of cholesteryl esters and presumably allowing more free cholesterol to enter an intrahepatic pool for biliary secretion.85

Pregnancy also induces changes in bile acid synthesis characterized by a decreased proportion of chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), thereby reducing the ability to solubilize cholesterol and favoring the precipitation of solid cholesterol crystals.77 These findings could be explained by changes in function of the pumps of the enterohepatic circulation due to gallbladder stasis induced by impaired motility function by estrogen and progesterone. Female sex hormones in pregnancy may directly regulate hepatic synthesis of individual bile acids. This interpretation is based on the studies of individual hormones. Progestins, when administrated in the absence of estrogen, exert little or no effect on bile acid composition or bile acid kinetics.50,86 By contrast, estrogen decreases the synthesis of CDCA but have little or no effect on cholic acid (CA) synthesis.1 These results imply the presence of an alteration in coupling of biliary lipids, consistent with the secretion of more lithogenic bile. In addition, alteration of bile acid pool may influence the physical-chemical properties of the bile acid pool and alter cholesterol absorption, cholesterol synthesis and bile acid synthesis.87–90 The cholesterol saturation index of fasting hepatic and gallbladder bile is increased during the second and the third trimesters of pregnancy.77 Hepatic hypersecretion of cholesterol and hydrophobic bile acids also favor cholesterol crystallization.91,92

After the first trimester of pregnancy, real-time ultrasonography shows that fasting gallbladder volume and postprandial residual volume are twice as large as in control healthy subjects, a condition pointing to gallbladder stasis. In early pregnancy, there is a 30% decrease in emptying rate, and in late pregnancy, incomplete gallbladder emptying leads to a large residual volume that causes biliary sludge and the retention of solid cholesterol crystals.52 Such abnormal motility patterns of the gallbladder also contribute to the increased risk of cholesterol gallstones. In addition, the lithogenic effects of supersaturated bile induced mainly by estrogen and dysfunctional gallbladder motility induced mainly by progesterone during pregnancy are hallmarked by the early appearance of biliary sludge, implying trapped cholesterol crystals and microlithiasis within the gallbladder mucin gel (Figure 1).93 Progesterone also causes a sluggish enterohepatic circulation of bile acids with secondary hyposecretion.77 In addition, gallbladder stasis progresses during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and an increase in fasting gallbladder and postprandial residual volumes is directly related to duration of gestation and circulating progesterone concentrations. Gallbladder volumes rapidly return to control values after delivery.8 Lastly, studies of muscle strips isolated from the gallbladders of a variety of species found that progesterone inhibits smooth muscle contraction.94–96 Increased levels of progesterone block the G-protein function in the gallbladder smooth muscle cells. In pregnancy, this effect is responsible for signal-transduction decoupling and impaired gallbladder contractility to cholecystokinin.97 Inhibition of gallbladder contraction could be due to the specific effect of progesterone on the availability of calcium for excitation-coupled contraction.

Although a critical role for estrogen in enhancing cholelithogenesis by activating classical ERa, but not ERβ in the liver has been established, the mechanisms mediating estrogen’s lithogenic actions on gallstone formation have become more complicated with the identification of a novel estrogen receptor, the G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30). Furthermore, GPR30 has been mapped to mouse chromosome 5 and is co-localized with a new gallstone gene Lith.18However, identifying the lithogenic mechanisms of GPR30 has been a focal point of interest because it remains unknown whether GPR30 plays a major role in estrogen-induced gallstones and whether it acts independently of or in conjunction with ERa on inducing gallstone formation. Obviously, more studies are needed to distinguish the lithogenic actions of GPR30 from those of ERα in the future.

Effect of Other Risk Factors on the Formation of Cholesterol Gallstones in Pregnant WomenDuring the period of a normal, healthy pregnancy, besides elevated levels of estrogen, the body undergoes substantial hormonal, immunological, and metabolic changes.98–101 Some of these alterations could become risk factors contributing to the formation of cholesterol gallstones in pregnant women, which include a high-cholesterol and high-fat diet, weight gain, and insulin resistance, as well as altered gut microbiota and immune function.102–108 Because many excellent review articles have summarized these topics in detail, we will briefly discuss it here. Obviously, to keep the fetus growing, pregnant women usually consume large amounts of nutrient food containing high calorie and high dietary fats, cholesterol, carbohydrates and proteins, thereby leading to a marked increase in body fat and a reduction in insulin sensitivity. Of special note is that in contrast to the obese state where they are detrimental to long-term health, excess adiposity and loss of insulin sensitivity are beneficial in the context of a normal pregnancy, as they support growth of the fetus and prepare the body for the energetic demands of lactation.109–111 Although reduced insulin sensitivity in pregnancy is still unknown, it has been correlated with changes in immune status in pregnancy, including elevated levels of circulating cytokines (e.g., TNFα and IL-6) that are thought to drive obesity-associated metabolic inflammation.112,113 In pregnancy, immunological changes occur at the placental interface to inhibit rejection of the fetus, while at the mother’s mucosal surfaces, elevated inflammatory responses often result in exacerbated bacterially mediated infectious diseases. These may increase a risk for biliary infection, gallbladder sludge, and cholesterol crystallization. Furthermore, bacterial load in the intestine is reported to increase over the course of gestation. Although these alterations may be beneficial in pregnancy, they could further enhance adiposity and worsen insulin insensitivity.114–118 Insulin resistance is a risk factor for incident gallbladder sludge and stones during pregnancy, even after adjustment for body mass index.106,119–121 It could promote hepatic cholesterol secretion, increase degrees of biliary cholesterol saturation, and impair cholecystokinin-stimulated gallbladder motility. Moreover, a recent large-scale human study has found that gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial community assembly are associated with the formation of cholesterol gallstones.122 Gut microbiota may have a role in the regulation of bile acid metabolism by reducing bile acid pool size and composition.123 Furthermore, human-associated microbial communities are linked with a variety of diseases, e.g., obesity, diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,124,125 all of which are risk factors for gallstone formation. It is very likely that bacteria colonized in the biliary tract may work as a nucleus for cholesterol crystallization. Therefore, changes in gut microbiota may be involved in gallstone formation, especially in pregnant women.126–129

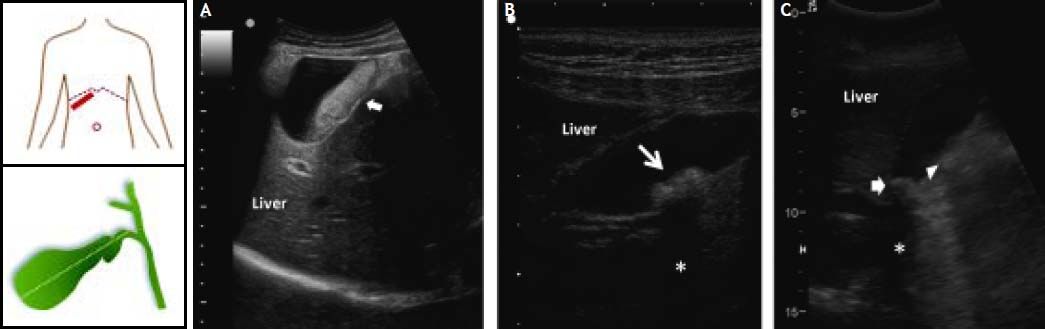

Diagnosis of Biliary Sludge and Gallstones in Pregnant WomenWhile pregnant women display a high incidence of biliary sludge, many of them are asymptomatic throughout the pregnancy and postpartum period.23,24,27 Because biliary sludge is often diagnosed incidentally by antenatal ultrasonography conducted for other reasons, regularly monitoring the development of gallstones in asymptomatic patients is worthwhile be performed, especially in high-risk women with parity. If biliary sludge is suspected in a pregnant woman, transabdominal ultrasonography is the first diagnostic test.130 Real-time ultrasonography can identify gallstones as small as 2 mm, with sensitivity > 95%. This technique is rapid, noninvasive and relatively low cost, as well as can be performed at the bedside and does not involve ionizing radiations. As shown in figure 2, biliary sludge is characterized by low amplitude, gravity-dependent sonographic echoes seen in the gallbladder, which does not cast an acoustic shadow.72,131 By contrast, ultrasound image can show a gallstone(s) in the gallbladder with typical acoustic shadow. As seen by polarizing light microscopy, biliary sludge consists mainly of plate-like cholesterol monohydrate crystals and calcium bilirubinate granules embedded in strands of mucin gel.75 However, because the sensitivity of ultrasonography for biliary sludge alone is only about 60%, further imaging testing and bile examination should be considered if the result of ultrasonography is negative and clinical suspicion remains high, for example, in a pregnant woman with recurring attacks of biliary colic.75

Ultrasonographic appearance of biliary sludge, gallstones, and gallstone plus biliary sludge in the gallbladder. The left cartoons depict the site of the oblique ultrasonographic scan at the right hypochondrium (top) and the resulting longitudinal section of gallbladder. A. A finely echogenic, dense, gravity-dependent, slowly mobile biliary sludge is seen occupying about 40% of the gallbladder lumen (thick arrows). The thickness of the gallbladder wall is not increased. B. Two mobile echogenic gallstones are indicated within the gallbladder lumen, layering on the distal wall. Each stone size is about 0.5 cm in diameter. C. A 1.5 cm gallstone in diameter (arrow) is detected in the gallbladder infundibulum and is surrounded by biliary sludge (triangle). The asterisk indicates the posterior acoustic shadowing typical of gallstones.

For a pregnant woman with suspected biliary sludge and/or gallstones who have a negative result from transabdominal ultrasonography, further diagnosing depends on the clinical symptoms, i.e., the presence or the absence of biliary colic. It is recommended examining gallbladder bile samples by polarizing light microscopy for pregnant women in whom the clinical suspicion of biliary sludge is high and in whom further treatment such as laparoscopic or elective cholecystectomy would be considered.132–134 If an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is required, gallbladder bile could be harvested during this procedure and analyzed by polarizing light microscopy. If an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is not required, a gallbladder bile sample could be obtained through duodenal intubation.75 Pregnant women with recurrent episodes of idiopathic acute pancreatitis generally undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (with shielding of the abdomen), and gallbladder bile can be collected from the duodenum or the common bile duct during this procedure.72,135,136 Pregnant women who have an indication for endoscopic ultrasonography, such as evaluation of abnormalities seen on previous imaging studies, should undergo this procedure first. Endoscopic ultrasonography is not recommended for pregnant women without another indication for the diagnosis. If biliary sludge is not identified on these imaging examinations, gallbladder bile samples can be collected for polarizing light microscopy. Further imaging examination such as computerized tomographic (CT) scanning is relatively high cost, low accurateness and availability.

During pregnancy, when common bile duct stones are suspected, radiographic imaging of the bile duct can be performed as long as the mother’s pelvis is shielded, the fetus is monitored, and the fetal dose of radiation is less than 5 radiation-absorbed doses.137,138 However, the safety of radiographic imaging is limited to women in their second and third trimesters. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography could be safely performed if necessary during pregnancy, with a premature delivery rate of less than 5%.139–141 Indications for this procedure include acute cholangitis, persistent jaundice, or severe pancreatitis with suspected choledocholithiasis. Contraindications include uncontrolled bleeding tendencies or inability to tolerate sedation or anesthesia.35 In addition to fetal risks, potential maternal complications include pancreatitis, biliary tract infection, and gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. The fetus should be shielded from radiation and fluoroscopy time minimized. In addition, fetal monitoring during any invasive procedures should be considered.142

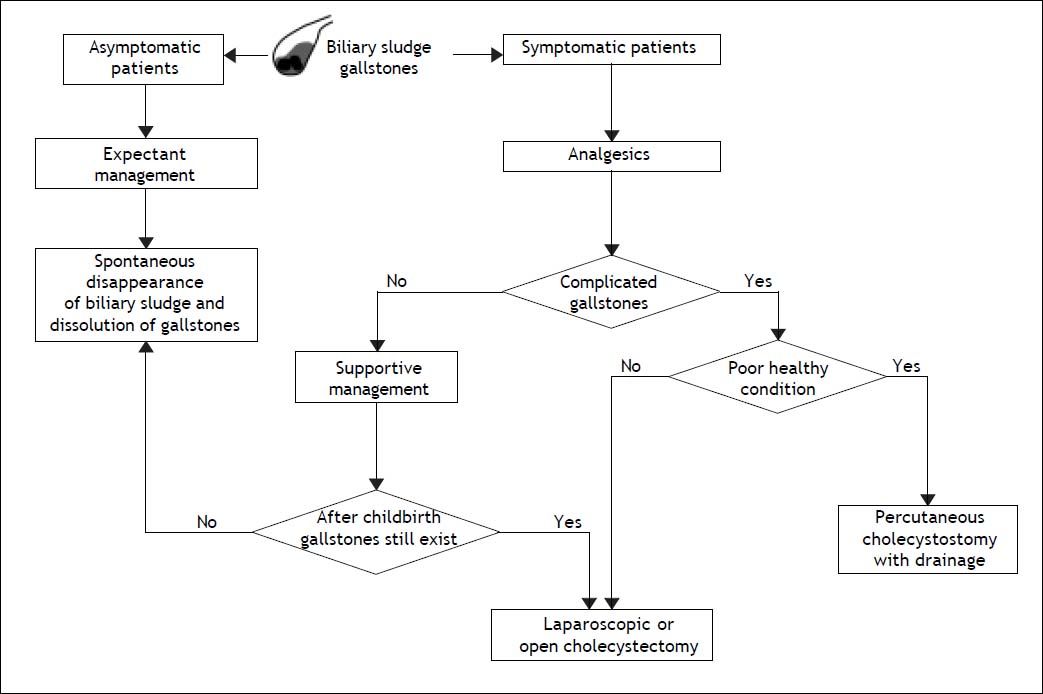

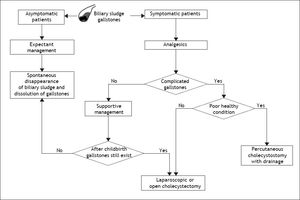

Prevention and Treatment of Biliary Sludge and Gallstones in Pregnant WomenFollowing acute appendicitis, gallbladder disease is the second most common indication for non-obstetric surgical intervention during pregnancy.63,143 Gallstones and biliary sludge are the most common causes of gallbladder disease in pregnant women. Pregnant women should be evaluated specifically for biliary sludge, microlithiasis, or gallstones only after they develop symptoms (Figure 3). If a specific cause leading to biliary sludge is detected, attempts should be made to eliminate it. Biliary sludge and gallstones should be considered similar in almost all respects.

Flow-chart depicting the standard therapy of biliary sludge and gallstones during pregnancy. For management purposes, biliary sludge and gallstones should be considered similar in almost all respects. Surgery generally is reserved for pregnant women with recurrent or unrelenting biliary pain refractory to medical management or with complications related to gallstones, including obstructive jaundice, acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis, or suspected peritonitis. For its safety, laparoscopic or elective cholecystectomy is one of the most common treatments for gallbladder gallstones in pregnant women, but it is recommended after the second trimester in order to reduce the rate of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor. If cholecystectomy is required during pregnancy, laparoscopic surgery is first recommended because of its relative safety. Of special note is that the timing of surgery is important. The effect of laparoscopic surgery on a developing fetus in the first trimester is unknown and surgery is more difficult in the third trimester with uterine enlargement. The second trimester, therefore, is believed to be the optimal time for cholecystectomy. A supportive management is highly recommended if possible, delaying more definitive treatment until after childbirth. See text for details.

Prevention of biliary sludge and gallstones in high-risk pregnant women has a rationale per se, since preventive measures may dramatically reduce the risk of cholecystectomy in pregnant and post-partum women.128 Potentially useful general measures might include constant physical activity although the ultimate beneficial role during pregnancy is controversial. Thus, asymptomatic pregnant women with biliary sludge should undergo careful follow-up and managed expectantly.75

No indication exists for drug prescription as preventive measure of biliary sludge and gallstones in pregnancy. This caution includes also cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) which has been used as prokinetic agent on the gallbladder and prevention of biliary sludge and gallstones in patients with gallbladder stasis because of prolonged total parenteral nutrition.70,144,145

Treatment during pregnancyGuidelines should be applied for optimal management of biliary sludge and gallstones in the pregnant woman. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has developed a general rating system to provide therapeutic guidance based on potential benefits and fetal risks, and drugs have been classified into categories A, B, C, D and X based on this system of classification.146

In asymptomatic pregnant women with biliary sludge and gallstones, expectant management is the general rule and litholysis is not indicated. However, in symptomatic pregnant women, there is a consensus concerning medical management of gallstones during pregnancy.72,128,135,147,148 Pain control is mandatory during pregnancy.

In a pregnant woman presenting with abdominal pain, true biliary colic should be distinguished from nonspecific abdominal discomfort. A laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy performed for true biliary colic is usually curative, but symptoms often persist if the procedure is performed in pregnant women with nonspecific dyspepsia and gallstones. Nevertheless, despite the availability of many imaging techniques that can be used to detect biliary sludge, microlithiasis, and gallstones in the gallbladder and the common bile duct, the diagnosis of biliary colic is ultimately based on clinical judgment.

Supportive management is highly recommended if possible, reserving definitive treatment after delivery. Women with uncomplicated biliary colic can be managed with intravenous hydration and narcotic pain control.149,150 Nevertheless, women who receive supportive treatment are prone to symptomatic relapses, which might increase the likelihood of premature delivery.149,150 No prospective data exist, moreover, comparing medical vs. surgical management with respect to symptomatic relapse, total number of hospital days, or rate of premature labor. With recurrent or complicated biliary tract disease, management becomes more controversial.

Lu, et al. have studied 76 women with 78 pregnancies admitted with biliary tract disease.149 Of the 63 women who presented with symptomatic cholelithiasis, 10 underwent surgery while pregnant. There were no deaths, preterm deliveries, or intensive care unit admission. Fifty-three patients were treated medically and their clinical courses were complicated by symptomatic relapse in 20 patients (38%), by labor induction to control biliary colic (8 patients), and by premature delivery in 2 patients. Each relapse in the medically managed group led to an additional five days stay in hospital. These findings suggest that surgical management of gallstones in pregnancy is safe and decreases days in hospital, as well as reduces the rate of labor induction and preterm delivery.149

The use of analgesics has successfully ameliorated biliary symptoms in 64% of symptomatic pregnant women.147 Surgery is generally reserved for pregnant women with recurrent or unrelenting biliary pain refractory to medical management or with gallstone-related complications.151 Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy is relatively safe and is the first-line option, but it is recommended after the second trimester in order to reduce the rates of spontaneous abortion and preterm labor.82,147,152–155 Papillotomy for choledocholithiasis yields relatively good results for mother and fetus.140 Selection criteria for surgery need to be carefully considered in pregnant women, as illustrated in figure 3.

These with only one episode of uncomplicated biliary colic are at moderate risk for future recurrence of pain and more serious complications, and up to 30% of women will not develop further clinical symptoms.75 Expectant management is still an option; in principle, oral litholysis is contraindicated in pregnancy. If symptoms or complications of biliary sludge or gallstones do recur, however, surgery should be considered. The indication for surgery is even stronger if more serious complications develop, such as acute cholecystitis, sepsis, gangrene, obstructive jaundice and suspected peritonitis, as well as acute pancreatitis induced by biliary sludge or microlithiasis.149,156–158 Surgery should be considered during initial hospitalization.

During pregnancy and when required, the first choice remains the laparoscopic, rather than the laparotomic cholecystectomy. Timing should be carefully considered as well.75 The effect of laparoscopic surgery on a developing fetus in the first trimester of pregnancy is unknown and surgery is more difficult in the third trimester with uterine enlargement. The second trimester, therefore, is believed to be the optimal time for cholecystectomy.154,159–162 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is performed safely with minimal fetal morbidity during this period.147,149,152,153 The risks of preterm labor or premature delivery in each trimester of pregnancy, however, are not clearly defined in the literature. If acute cholecystitis or cholangitis develops, earlier cholecystectomy should be considered.163

However, if a pregnant woman is under a poor healthy condition for surgery, percutaneous cholecystostomy with drainage should be considered.75,164–166 The long-term efficacy of these methods has not been proven by clinical trials and these approaches should be used only in pregnant women who require emergency therapy but are not good candidates for cholecystectomy. The efficacy of percutaneous cholecystostomy with drainage in the treatment of biliary sludge has not been well established.75

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a litholytic bile salt (see below) and is used in a subgroup of symptomatic gallstone patients. Although UDCA is the treatment of choice for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy167,168 and is classified as B drug by FDA (i.e., no evidence of risk in studies), it is not used during pregnancy for biliary sludge and gallstone dissolution. Same would apply to ezetimibe, another agent acting on gallstone dissolution (see below).

Management post pregnancyTherapeutic options of biliary sludge and gallstones after pregnancy should follow the general guidelines, including expectant management in asymptomatic patients (no consensus about the need for prophylactic cholecystectomy), and cholecystectomy in previously symptomatic patients or those who will become symptomatic after pregnancy. In a small subgroup of women, oral litholysis might have a role, and might include:

- •

Administration of the cholelitholytic agent UDCA;75 and

- •

Administration of the potent intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe.128,169,170

The effect of UDCA, a hydrophilic bile acid, has been extensively studied for the dissolution of cholesterol gallstones in patients.171 UDCA has been recommended as first-line pharmacological therapy in a subgroup of symptomatic patients with small, radiolucent cholesterol gallstones, and its long-term administration has been shown to promote the dissolution of cholesterol gallstones and to prevent the recurrence of gallstones.92,172 The potential cholelitholytic mechanisms of UDCA involve the formation of a liquid crystalline mesophase.173 It favors the formation of numerous vesicles that are composed predominantly of phospholipids in bile so that the growth of liquid crystals on the cholesterol monohydrate surface and their subsequent dispersions might occur during gallstone dissolution. Consequently, liquid crystalline dissolution allows the transport of a great amount of cholesterol from stones, which is excreted into the duodenum and eventually in the faces.173 In patients with a rapid loss of body weight, UDCA reduces the incidence of gallstones by 50 to 100%.174–176 In addition, in patients with biliary sludge and idiopathic pancreatitis, after initial treatment with UDCA to dissolve cholesterol monohydrate crystals, ongoing maintenance therapy successfully prevents the recurrence of biliary sludge and pancreatitis.26

Ezetimibe, 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-(3R)-[3-(4-fluorophenyl)-(3S)-hydroxypropyl]-(4S)-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-azetidinone, is a highly selective intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitor that effectively and potently prevents the absorption of cholesterol by inhibiting the uptake of dietary and biliary cholesterol across the brush border membrane of the enterocyte through the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) pathway, possibly a transporter-facilitated mechanism.169 It could reduce cholesterol concentrations of the liver, which in turn diminish the bioavailability of cholesterol for biliary secretion.169 Ezetimibe has been found to induce a striking dose-dependent decrease in intestinal cholesterol absorption efficiency, coupled with a significant dose-dependent reduction in biliary cholesterol output and gallstone prevalence rate in gallstone-susceptible mice, even under high dietary cholesterol loads. Of note is that ezetimibe promotes the dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by forming an abundance of unsaturated micelles. Ezetimibe could protect gallbladder motility function by desaturating bile.177 Furthermore, in a small number of patients with gallstones, ezetimibe has been revealed to significantly reduce biliary cholesterol saturation and retard cholesterol crystallization in bile.177 These observations clearly demonstrate that ezetimibe is a novel and potential cholelitholytic agent for preventing or treating cholesterol gallstone disease not only in mice but also in humans. To evaluate treatment time, response rate and overall cost-benefit analysis, a more detailed, long-term human study needs to be performed.

More recently, we found from a preliminary study that ezetimibe prevents the formation of E2-induced cholesterol gallstones by inhibiting intestinal cholesterol absorption. The bioavailability of intestinal source of cholesterol for biliary secretion is markedly reduced and bile is desaturated in mice even on the lithogenic diet. Also, ezetimibe does not influence mRNA levels of the Erα, Erβ and Gpr30genes in the liver. Therefore, these results show that ezetimibe is a potential cholelitholytic agent for preventing or treating E2-induced gallstones. These findings may provide an effective novel strategy for the prevention of cholesterol gallstones, particularly in women and patients exposed to high levels of estrogen. Further clinical studies are warranted in this respect.

Because ezetimibe and UDCA promote the dissolution of cholesterol gallstones by two distinct mechanisms via the formation of an unsaturated micelle and a liquid crystalline mesophase, respectively, it is highly likely that biliary sludge could be prevented and cholesterol gallstones could be dissolved faster by a combination therapy of ezetimibe and UDCA even in pregnant in postpartum women. A major limitation of oral litholysis, however, is the high recurrence rate of gallstones (10% per year and up to 45-50% by 5 years).178,179

Conclusions and Future DirectionsObviously, during pregnancy, bile becomes lithogenic because of a significant increase in estrogen levels, which lead to hepatic cholesterol hypersecretion and biliary lithogenicity. In addition, increased progesterone concentrations impair gallbladder motility function, with the resulting increase in fasting gallbladder volume and bile stasis. Such abnormalities greatly promote the formation of biliary sludge and gallstones. Because plasma concentrations of female sex hormones, especially estrogen, increase linearly with the duration of gestation, the risk of gallstone formation becomes higher in the third trimester of pregnancy. Increasing parity is also a risk factor for gallstones, especially in younger women. Similarly to non-pregnant women, pregnant women are indeed exposed to the whole spectrum of the natural history of biliary sludge and gallstones. Clinical features include no symptoms, one or more episodes of biliary colicky pain and sludge/gallstone-related complications. Due to its noninvasive features, transabdominal ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic approach in asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant patients. All available therapeutic options (apart from oral litholysis with UDCA) must be kept accessible in symptomatic patients (i.e. supportive care in patients with only one episode of biliary colic, laparoscopic cholecystectomy followed by open cholecystectomy in high-risk cases, and ERCP if biliary pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis, and cholangitis develop). Open issues for future research agenda must include ways to prevent the formation of biliary sludge and gallstones before and during pregnancy, the role of lifestyles, novel therapeutic medical agents to be tested in larger groups of patients (e.g., ezetimibe), and safe cholelitholytic agents during pregnancy, as well as ways to better prevent and treat gallstone complications.

AcknowledgmentThis work was supported in part by research grants DK73917 and DK101793 (to D.Q.-H.W.) and DK92779 (to M.L.) from the National Institutes of Health (US Public Health Service) and research grant MRAR08P011-2012 (to P.P.) from Italian Agency of Drug (AIFA).

Conflict of InterestNone of the authors has any financial or any conflict of interest related to the content of this manuscript.