Background. Hepatitis A is the most common type of viral hepatitis in Mexico. The change of hepatitis A epidemiology in Mexico from high to intermediate endemicity leads to increasing susceptible adults for severe illness. Objective. To describe the clinical characteristics and hospital outcome of adult patients with acute hepatitis A infection, and determine risk factor for mortality.

Material and methods. This is a retrospective observational, multicentre study in Mexico City and in Guatemala City. All inhospital patients were followed until discharge or death. Risk factors for death/acute liver failure were identified.

Results. Forty seven patients were analyzed, sixty percent were male, the prodrome phase was from 3 to 30 days. The three most common symptoms were fever, malaise and jaundice, with 87%, 74% and 62% respectively. The incidence of patients who were treated with antibiotics before hospital admission was up to 34%. Unnecessary imaging studies and out of guidelines drugs were used. Presence of encephalopathy, leukocytes > 19,000/mL, blood urea nitrogen > 36 mg/dL, creatinine > 2 mg/dL, albumin < 2.5 mg/dL andtotal bilirubin > 9.6 mg/dL, are predictors of mortality. Serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL has the best sensibility and specificity for predicting fulminant hepatitis/death.

Conclusion. Acute hepatitis A infection in adults is associated some unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Could be associated with fulminant hepatitis, and a creatinine value > 2 mg/dL is the best predictor for fulminant hepatitis and death.

Hepatitis A is an infectious disease caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), it is self-limited and do not cause chronic liver disease. HAV is a single stranded RNA virus without envelope, which is transmitted by fecal-oral route with contaminated food and water, and it can also generate epidemic outbreaks. HAV generates acute hepatocellular damage mediated by the host immune response, not directly by the virus, as HAV is not a cytopathic virus. Infection with HAV is prevalent throughout the world with different epidemiology according to the age of exposition and immunization for HAV. Approximately 1.4 million cases of hepatitis A occur each year worldwide.1 The epidemiology varies with the socioeconomic conditions, with high endemicity in countries with poor hygiene and sanitary standards.

Hepatitis A is the most common type of viral hepatitis in México. In published epidemiological report from 2000 to 2007 there were 192,588 reported cases of hepatitis, being 79% secondary to HAV infection.2 In the early seventies according to the frequency of the HAV infection, Mexico was considered a country of high endemicity of hepatitis A infection.3 Twenty years ago 90 to 100% of children between 1-5 years old were IgG-HAV positive, indicating a very early exposure of children to HAV.4 In children Hepatitis A disease tends to be asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic.1 After the cholera outbreak in 1994 in Mexico, there were implemented environmental hygiene and sanitary improve, decreasing gastrointestinal infections, including hepatitis A. In earlier studies from 1991 to 2002 a shift from high to intermediate endemicity was observed. In this study child IgG antibodies were detected in 51% of children at the age of eight.2 The same shift in epidemiology has been observed in other countries including United states, Canada, England and Korea.1,5-7 The reduction of hepatitis A infection in children has been declining the prevalence of natural immunization in this age group, leading to adults be susceptible to hepatitis A infection with a more severe illness. The clinical course varies with age, near 80% of the HAV infections in patients less than 6 years old are asymptomatic, while about 80% of infected adults manifest a severe hepatitis, with higher grade and prolonged cholestasis, intrahepatic or extrahepatic complications, or even fulminant hepatitis.3,8,9 The most frequent extrahepatic complications reported in acute HAV infection are acalculous cholecystitis, and acute renal failure.10

Only 5% of patients younger than 5 years old are hospitalized for an acute hepatitis A infection, compared with 34% of infected patients over 60 years old. The incidence of fulminant hepatitis in general population is 0.3%, it increases to 1.8% in patients over 49 years old. The mortality of HAV infection is low but it increases with age, as the incidence of complications increases. The hepatitis A mortality in general population is 0.2%, and increases to 1% in patients over 49 years old.11 Complications of acute hepatitis A infection in adult increases directly proportional with advancing age. Other risk factors for the development of fulminant hepatitis is a previous hepatic disease, HIV, and chronic diseases.12,13

The change of hepatitis A epidemiology in Mexico from high to intermediate endemicity, leads to increasing susceptible adults for severe illness. However there are few studies of clinical course, hospital management, and risk factors for complications in adult patient with acute hepatitis A infection.

ObjectiveThe objective of this study is to describe the clinical characteristics and hospital outcome of adult patients with acute hepatitis A infection, and to determine risk factor for mortality.

Material and MethodsStudy populationThis is a retrospective observational, in two private hospitals, in Mexico City and Guatemala City. We identified in the database of clinical laboratory of Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation (Mexico) and Unit of Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Hospital Las Américas Hospital (Guatemala), all the patients over 18 years old with reactive IgM for hepatitis A, who were hospitalized during January 1st 2007, to December 31st 2010. We collected from clinical record of each patient the clinical and biochemical, and imaging data, treatment before admission and management during hospitalization, as well as significant clinical outcomes. We analyzed risk factors for mortality. All patients younger than 18 years, those who were hospitalized for a diagnosis different from acute hepatitis A infection and those who were not hospitalized were excluded. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of The Medica Sur Clinic and Foundation as conforming to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Laboratory testsThe measurement of HAV IgM assay was performed using the Access HAV IgM (Beckman Coulter; CA, USA); an immunoassay based on the principle of immunocapture with a reaction vessel chemiluminiscent substrate Lumi-Phos 530. The light generated by the enzymatic reaction is measured using a luminometer. The amount of light measured for each sample determines the presence or absence of IgM antibodies to HAV, compared with a defined cutoff value.

The hepatic function test was determined by the Beckman Coulter-Synchron LX20 Clinical system (Beckman Coulter; CA, USA); with a colorimetric principle for albumin, total proteins, globulins, and bilirrubins, and by enzymatic methods for transaminases.

Imaging testWe defined acalculous cholecystitis as inflammation of the gallbladder wall, without calculi in its interior, confirmed trough ultrasound or CT scan.

Statistical analysisThe variables are described by measures of central tendency and dispersion. To discriminate those factors associated with mortality in the cohort area under the curve was calculated. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

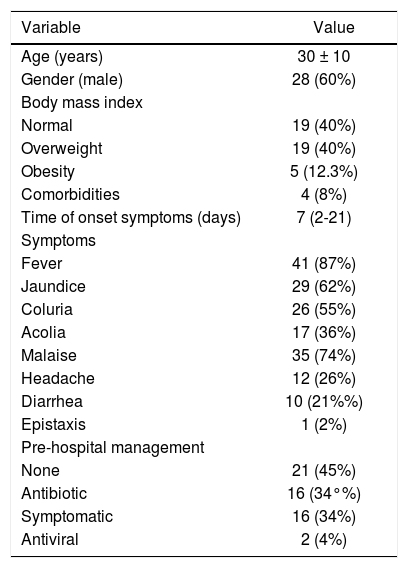

ResultsA total 68 of patients IgM-HAV reactive were detected in the period from January 1st 2007 to December 31st 2010 in the two centers. Twenty one patients were excluded, 20 from Mexico and 1 from Guatemala. Fourteen of the excluded patients were not hospitalized, 5 were admitted with other diagnosis, and two patients had no complete laboratory information. A total of 47 patients were analyzed, from which 60% (n = 28) of all the analyzed subjects were male. Baseline characteristics of the study group are described in table 1. In relation to anthropometry we divided all the patients according to their BMI in normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29 kg/m2), obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2). Most patients were in the normal weight group and overweight with 40% in each group (n = 19 in each group), and only 10.5% (n = 5) were obese. Seventeen percent (n = 8) of the analyzed patients had a history of smoking and only 8.5% (n = 4) of patients with history of alcohol intake. According to the medical history the vast majority of patients had no comorbidities (92%, n = 43), and do not consume any medication (76%, n = 36).

Baseline characteristics of the population.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30 ± 10 |

| Gender (male) | 28 (60%) |

| Body mass index | |

| Normal | 19 (40%) |

| Overweight | 19 (40%) |

| Obesity | 5 (12.3%) |

| Comorbidities | 4 (8%) |

| Time of onset symptoms (days) | 7 (2-21) |

| Symptoms | |

| Fever | 41 (87%) |

| Jaundice | 29 (62%) |

| Coluria | 26 (55%) |

| Acolia | 17 (36%) |

| Malaise | 35 (74%) |

| Headache | 12 (26%) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (21%%) |

| Epistaxis | 1 (2%) |

| Pre-hospital management | |

| None | 21 (45%) |

| Antibiotic | 16 (34°%) |

| Symptomatic | 16 (34%) |

| Antiviral | 2 (4%) |

The time of onset of symptoms before hospital admission, was of 7.5 ± 6 days (range 2-30). As for the self-reported symptoms at hospital admission, the three most common symptoms were fever, malaise and jaundice, with 87%, 74% and 62% respectively. Other symptoms that occur less frequently include headache (26%) and diarrhea (21%). As symptoms associated with coagulation defects secondary to severe liver damage only one patient (2%) reported epistaxis at hospital admission.

The incidence of patients who sought medical consultation before hospital admission, who were treated with antibiotics was up to 34% (n = 16), even at 4% (n = 2) an empirical antiviral management was indicated.

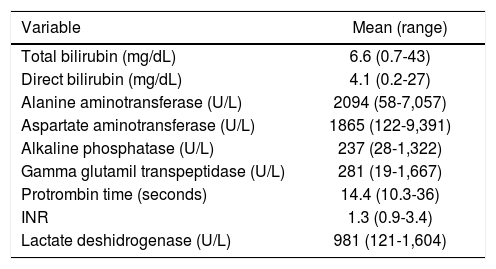

In the biochemical variables the liver function test in acute hepatitis manifests as a mixed pattern, with important rate of cholestasis, and hepatocellular damage. In this study the mean total bilirubin was 6.6 mg/dL with a maximum of up to 43 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 237 U/L (28-1322 U/L), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) 281 U/L (19-1,667 U/L), and lactate deshidrogenase (LDH) 981 U/L (121-1604 U/L); in the same way there is also an important hepatocellular damage, with significant elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) with an average of 2,094 U/L and 1,865 U/L respectively (Table 2).

Biochemical variables at baseline.

| Variable | Mean (range) |

|---|---|

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 6.6 (0.7-43) |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 4.1 (0.2-27) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 2094 (58-7,057) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 1865 (122-9,391) |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 237 (28-1,322) |

| Gamma glutamil transpeptidase (U/L) | 281 (19-1,667) |

| Protrombin time (seconds) | 14.4 (10.3-36) |

| INR | 1.3 (0.9-3.4) |

| Lactate deshidrogenase (U/L) | 981 (121-1,604) |

We found 8.5% (n = 4) of fulminant hepatitis. Analyzing each of them all has a prior factor that predisposes to the development of fulminant hepatitis. All of them were managed in the intensive care unit, and died.

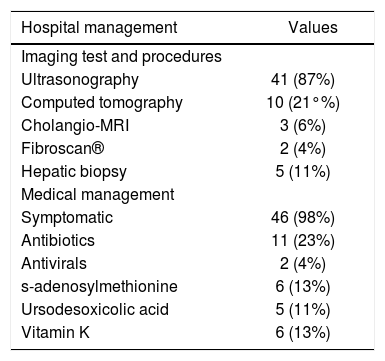

As for the hospital management in 87% of patients (n = 41), an abdominal ultrasound was requested as part of initial evaluation. In 21% of patients (n = 10), ultrasonographic finding of acalculous cholecystitis was found. Nonspecific changes in echogenicity of the liver was found by ultrasound in 30% (n = 14), and in 32% (n = 15) hepatomegaly was reported. Splenomegaly was found only in 6.4%, and ascitis in 2.1% (n = 3, and n = 1 respectively). Other more expensive and unnecessary imaging studies were requested including Fibroscan®, Cholangio-MRI and liver biopsy (4.2%, 7.1%, 10.8% respectively). In pharmacological management, all patients receive symptomatic treatment, including antipyretics, antiemetics and proton pump inhibitors. Up to 27% (n = 13) of the study subjects received antibiotic or antiviral treatment empirically. We found that other out of guidelines drugs were used in acute hepatitis such as s-adenosylmethionine and ursodesoxicolic acid in 13% and 11% (n = 5 and n = 6 respectively) patients. In all the four cases of fulminant hepatitis this drugs were used (Table 3).

Hospital management during hepatitis A virus infection.

| Hospital management | Values |

|---|---|

| Imaging test and procedures | |

| Ultrasonography | 41 (87%) |

| Computed tomography | 10 (21°%) |

| Cholangio-MRI | 3 (6%) |

| Fibroscan® | 2 (4%) |

| Hepatic biopsy | 5 (11%) |

| Medical management | |

| Symptomatic | 46 (98%) |

| Antibiotics | 11 (23%) |

| Antivirals | 2 (4%) |

| s-adenosylmethionine | 6 (13%) |

| Ursodesoxicolic acid | 5 (11%) |

| Vitamin K | 6 (13%) |

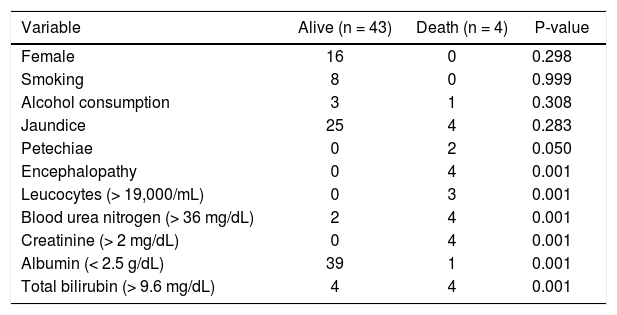

We compared clinical and laboratory factors in patients who survived and patients who died, to determine which variables were associated with mortality. Smoking, alcohol consumption, jaundice, and petechiae are not determinants of mortality. Moreover, the presence of encephalopathy, leukocytes > 19,000/mL, blood urea nitrogen > 36 mg/dL, creatinine > 2 mg/dL, albumin < 2.5 mg/dL and total bilirubin > 9.6 mg/dL, are predictors of mortality, all statistically significant (Table 4).

Clinical and laboratory factors according to survival status.

| Variable | Alive (n = 43) | Death (n = 4) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 16 | 0 | 0.298 |

| Smoking | 8 | 0 | 0.999 |

| Alcohol consumption | 3 | 1 | 0.308 |

| Jaundice | 25 | 4 | 0.283 |

| Petechiae | 0 | 2 | 0.050 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Leucocytes (> 19,000/mL) | 0 | 3 | 0.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (> 36 mg/dL) | 2 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (> 2 mg/dL) | 0 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Albumin (< 2.5 g/dL) | 39 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (> 9.6 mg/dL) | 4 | 4 | 0.001 |

We analyze ROC curves from the biochemical variables to see which one is the best predictor of mortality. Serum creatinine > 2 mg/dL has the best sensibility and specificity for predicting bad outcome for HAV infection, with fulminant hepatitis and death (Figure 1).

We analyze dot plot graphics according survival status. In all the graphics, there is overlap of the points, except for creatinine (> 2 mg/dL) which is the best biochemical predictor of mortality (Figure 2).

DiscussionThe main etiology of liver disease in Mexico is alcohol and viral hepatitis, and hepatitis A is the most common type of viral hepatitis in Mexico. Mexico is a country with epidemiological change moving from high to intermediate endemicity, leading to more susceptible adults for acute hepatitis A.3 Acute hepatitis A infection is usually a mild disease in children; however adults are more susceptible to severe clinical course and complications. As we know elderly patients have higher incidence of acute liver failure and higher mortality.14 Persons with chronic liver disease may suffer descompensation of the liver disease and are at a higher risk for fulminant hepatitis after acute hepatitis A infection.15

In general, hepatitis A in adults has a benign clinical course without complications in most patients. According to results obtained in this study, fever, jaundice and malaise are the three most common symptoms present at admission, with a mixed pattern with significant cholestasis and hepatocellular damage, and up to 21% have an abdominal ultrasound consistent with acalcolous cholecystitis. The prevalence of fulminant hepatitis and mortality was 8.6% (4 patients).

As we know the presence of chronic liver disease and age are the principal risk factors for the development of fulminant hepatitis.14 In our study we found that three of the four fulminant hepatitis had a previous hepatic disease. The first one developed a concomitant acute hepatitis B virus infection, the second one had an hepatic metastasis from a colorectal adenocarcinoma, the third one had a chronic alcohol consumption without known cirrhosis; the fourth one the only possible association was a chronic acetaminophen consumption for a chronic lumbar pain and IgG for cytomegalovirus.

In our study we analyzed the predisposing factors for the development of fulminant hepatitis and mortality. We found that leucocytes > 19,000/mL, blood urea nitrogen > 36 mg/dL, creatinine > 2 mg/dL, albumin < 2.5 g/dL and total bilirubin > 9.6 mg/dL, are predictors of mortality. In contrast, in a previous study of Cho et al. they analyzed the initial predictors for severe acute hepatitis A, they found that low albumin (< 3.5 g/dL), low cholesterol (< 90 mg/dL) and high ALT (> 3,400 U/L) are independent predictors for development of severe acute hepatitis A.16

We analyzed all the predisposing factors for fulminant hepatitis with ROC curves, and dot plot graphics to determine the best predictor for fulminant hepatitis and mortality. Being creatinine > 2 mg/dL those which has the best sensitivity and specificity for detecting fulminant hepatitis and mortality, without overlapping.

As we know from previous studies acute renal failure is a very rare complication in adult patients hospitalized for non fulminant acute hepatitis A, and is present in more than 80% of patients with fulminant hepatitis.17 In contrast results from a recent Korean study18 revealed that acute hepatitis A associated acute renal failure is not rare, and was present in 5.7% of acute hepatitis A patients, none of those patients died, and all recovered renal function completely. This results are completely opposite from data from previous studies and our study. This show the heterogeneity of this common disease.

This study has some limitations principally the reduced small number of patients, limitating multivariate analysis. Even though, there is few information of clinical presentation, clinical course, and predictors for fulminant hepatitis from acute hepatitis A in adults in Mexico. Additional findings from our study, we can realize that physicians in Mexico still have difficulty in rapid diagnosis of acute hepatitis A, requiring unnecessary imaging studies and treatment out from acute hepatitis A guidelines.

In conclusion, hepatitis A infection in adult population is associated some unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Could be associated with fulminant hepatitis, and a creatinine value greater than 2 mg/dL is the best predictor for fulminant hepatitis and mortality.

Financial SupportThis study was partially supported by an educational grant from Medica Sur Clinic & Foundation.