Introduction. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious complication seen in hospitalized, medically-ill patients. Evaluation for HIT using a commercially-available ELISA-based test has become increasingly common; however, it does have a high false positive rate. Implications of HIT testing in patients with cirrhosis have not yet been reported.

Material and methods. We conducted a single-institution, retrospective review of all patients with cirrhosis admitted over a 29-month period. The student’s t-test and the χ2 test were used for comparisons. We performed a stratified survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier and log rank testing.

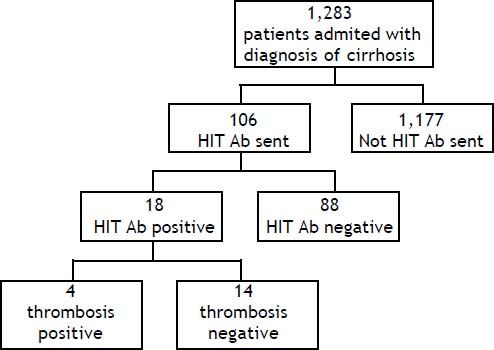

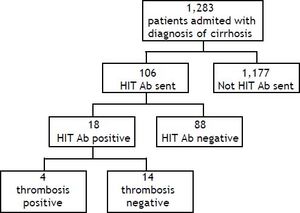

Results. A total of 1,305 patients had a HIT Ab sent during the study period. Of these patients, 106 had cirrhosis and were included in the study. Eighteen (17%) of the patients with cirrhosis were HIT Ab positive and four of the eighteen had a positive Serotonin Release Assay (SRA) confirmatory test. No difference was found in platelet nadir, thrombotic rate, length of stay, and patient survival between patients with positive HIT Ab and negative HIT Ab testing. No consistent treatment was used among patients who were HIT Ab positive, despite hematology service consultation. Patients who were HIT Ab negative were more likely to have undergone liver transplantation compared to those who were positive (27 vs. 5.5%, respectively; p = 0.048).

Conclusion. Our data suggest that HIT Ab testing is over-used in patients with cirrhosis and is poorly predictive of outcomes. With a poor positive predictive value, HIT testing may add unnecessary complexity to an already complicated patient population.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a relatively common complication of heparin use, occurring in up to 2.5% of hospitalized patients.1 Antibodies directed at platelet-factor 4 (PF4)-heparin complexes activate platelets, monocytes, and endothelium, ultimately leading to a significantly increased risk for arterial and venous thromboembolism.2,3 Approximately 50% of patients will have a thrombosis at time of diagnosis, with 50% of remaining patients developing a thrombotic event within 30 days of recognition of HIT.4 Alternative anticoagulation, initially with a direct thrombin inhibitor, is therefore recommended.5 Concern for HIT is raised when patients on heparin-based anticoagulation have an otherwise unexplained drop in their platelet count, typically greater than 50% of baseline.5,6 Increased awareness and availability of highly sensitive ELISA-based assays have led to less discriminate testing for HIT. Unfortunately the relatively low specificity (74-86%)7 and corresponding high false-positive rate, of HIT antibody (Ab) testing may expose a subset of patients to unnecessary treatment with alternative anticoagulation, delay other treatments, and prolong hospital stays.

Patients with cirrhosis often have exposure to heparin products while in the hospital, either for DVT prophylaxis, dialysis, or treatment of thrombus.8,9 HIT Ab testing may be especially problematic in patients with cirrhosis, as these patients often have baseline thrombocytopenia and abnormal laboratory coagulation values,10 which complicates management decisions if testing returns positive. Additionally, the low specificity and high false positive result uniquely impacts patients with cirrhosis who are candidates for liver transplantation, as heparin products are typically used in the peri-transplant period. The 4T score for prediction of HIT has been described in the literature, and functions to stratify patients into low, medium and high probability in developing HIT. The pretest scoring system consists of the presence of thrombocytopenia, timing of platelet count fall, thrombosis or other sequelae, and evaluating for other causes of thrombocytopenia.11 It has been shown to have a high negative predictive value with a poor positive predictive value.12 While this test has been validated in cohorts of patient populations, the utility in patients with cirrhosis has not yet been established. Therefore there is little pretest guidance in the development of HIT in this population.

Furthermore, there are no evidence-based guidelines on how to approach patients with cirrhosis who are HIT Ab positive and the consequences of positive tests. In order to better characterize the utility of HIT Ab testing in patients with cirrhosis, we performed a study to determine the prevalence of HIT Ab testing, it’s predictive value in establishing the diagnosis of HIT and its impact on clinical outcomes in a retrospective cohort of patients with cirrhosis.

Material and MethodsIn this Institutional Review Board approved, retrospective chart review, we included inpatients at our tertiary care liver transplant center between 7/7/2008 and 9/17/2010. The start date for the study, coincided with our institution’s adoption of the spectroscopy-based immunoassay for HIT testing. Patients were identified by ICD-9 codes (code 571) for cirrhosis and were included if they were tested for HIT antibody ELISA. We queried our electronic medical record by using our institutional Enterprise Database Warehouse (EDW). The EDW is a single, integrated database of clinical and research data from all patients receiving treatment through Northwestern Healthcare affiliates.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was then confirmed by manual review of the clinical chart by two independent reviewers (KM and LK). Patient demographics, co-morbid conditions, complications of end-stage liver disease, and laboratory values including platelet count, platelet nadir, and standard coagulation parameters (prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR)) were recorded. Clinical outcomes, including development of thrombosis, receipt of liver transplant, use of anticoagulation, and mortality, were also documented. Development of thrombus was defined as either deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) as documented by imaging modality including compression ultrasonography, CT angiography, or V/Q scan.

HIT antibody detectionScreening for anti-platelet factor 4 (PF4)/heparin antibodies was performed using a commercially available polyanion, solid phase immunoassay (GTI-PF4 ELISA; GTI, Waukesha, WI). The optical density (OD) of the resultant color that develops is measured in a spectrophotometer, with a positive result being defined by an OD of > 0.40. Confirmatory testing for positive HIT Ab was performed using a serotonin release assay (SRA), performed at the Blood Center of Wisconsin. The SRA is a functional assay that measures heparin-dependent platelet activation using donor platelets containing radioactive 14C-serotonin incubated with patient serum and both low (< 1.0 U/mL) and high (> 10 U/mL) concentrations of heparin. SRA is defined as positive at greater than 20% 14C-serotonin release on exposure to patient serum with low dose heparin, and < 20% release in the presence of high heparin concentration. Sensitivity and specificity of the SRA is reported to be > 95% with experienced laboratories.13 For the sensitivity and specificity calculations we defined HIT antibody positivity as having a positive HIT antibody and a positive SRA or the development of a thrombosis.

Statistical analysisThe group differences in continuous and binary variables were assessed using t-tests and χ2 tests, respectively. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and all tests were two-sided. We conducted a survival analysis stratified by HIT Ab status by constructing a Kaplan Meier curve. Significance was tested for using log-rank testing. All patients who were transplanted were censored at the time of transplantation. Two separate reviewers completed the data analysis to ensure congruency in the final reported values. SAS 9.2 software (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) was used to perform statistical analysis.

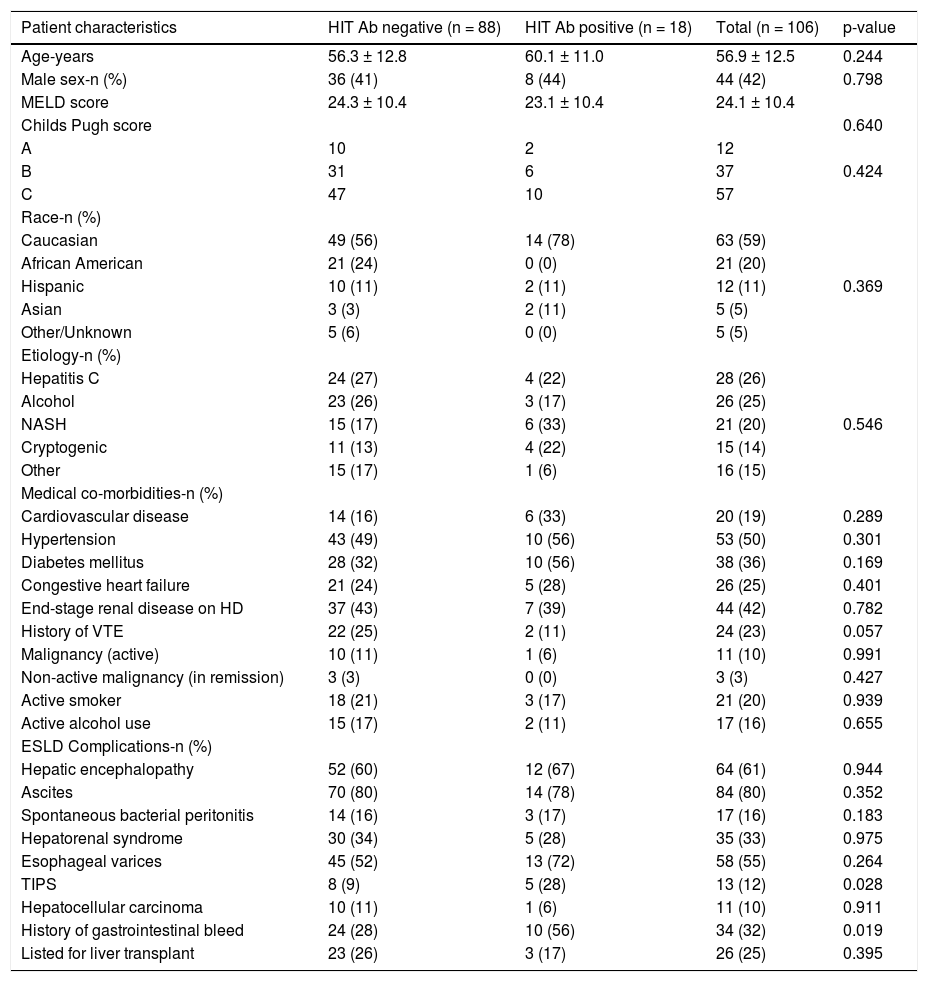

ResultsPatientsDuring the study period a total of 1,305 HIT Ab tests were sent at our institution. A total of 1,283 patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis were admitted over the 29-month period, from 7/7/2008 to 9/ 17/2010. One hundred and six patients with a diagnosis of cirrhosis had a HIT antibody test sent during the study period (Figure 1). The main demographic and clinical characteristics of our cohort are summarized in table 1. Patients were primarily female (58.5%), Caucasian (59.4%), and had a mean age of 57.0 ± 12.5 years. Hepatitis C (26.4%) and alcohol (24.5%) represented the most frequent etiology of cirrhosis in our population. Of the 106 patients, 64 (60.3%) were exposed to unfractionated heparin (UFH), 21 (19.8%) were exposed to low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH, either enoxaparin or dalteparin), and 21 (19.8%) had no documented heparin exposure.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | HIT Ab negative (n = 88) | HIT Ab positive (n = 18) | Total (n = 106) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-years | 56.3 ± 12.8 | 60.1 ± 11.0 | 56.9 ± 12.5 | 0.244 |

| Male sex-n (%) | 36 (41) | 8 (44) | 44 (42) | 0.798 |

| MELD score | 24.3 ± 10.4 | 23.1 ± 10.4 | 24.1 ± 10.4 | |

| Childs Pugh score | 0.640 | |||

| A | 10 | 2 | 12 | |

| B | 31 | 6 | 37 | 0.424 |

| C | 47 | 10 | 57 | |

| Race-n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 49 (56) | 14 (78) | 63 (59) | |

| African American | 21 (24) | 0 (0) | 21 (20) | |

| Hispanic | 10 (11) | 2 (11) | 12 (11) | 0.369 |

| Asian | 3 (3) | 2 (11) | 5 (5) | |

| Other/Unknown | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | |

| Etiology-n (%) | ||||

| Hepatitis C | 24 (27) | 4 (22) | 28 (26) | |

| Alcohol | 23 (26) | 3 (17) | 26 (25) | |

| NASH | 15 (17) | 6 (33) | 21 (20) | 0.546 |

| Cryptogenic | 11 (13) | 4 (22) | 15 (14) | |

| Other | 15 (17) | 1 (6) | 16 (15) | |

| Medical co-morbidities-n (%) | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 14 (16) | 6 (33) | 20 (19) | 0.289 |

| Hypertension | 43 (49) | 10 (56) | 53 (50) | 0.301 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 (32) | 10 (56) | 38 (36) | 0.169 |

| Congestive heart failure | 21 (24) | 5 (28) | 26 (25) | 0.401 |

| End-stage renal disease on HD | 37 (43) | 7 (39) | 44 (42) | 0.782 |

| History of VTE | 22 (25) | 2 (11) | 24 (23) | 0.057 |

| Malignancy (active) | 10 (11) | 1 (6) | 11 (10) | 0.991 |

| Non-active malignancy (in remission) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 0.427 |

| Active smoker | 18 (21) | 3 (17) | 21 (20) | 0.939 |

| Active alcohol use | 15 (17) | 2 (11) | 17 (16) | 0.655 |

| ESLD Complications-n (%) | ||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 52 (60) | 12 (67) | 64 (61) | 0.944 |

| Ascites | 70 (80) | 14 (78) | 84 (80) | 0.352 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 14 (16) | 3 (17) | 17 (16) | 0.183 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 30 (34) | 5 (28) | 35 (33) | 0.975 |

| Esophageal varices | 45 (52) | 13 (72) | 58 (55) | 0.264 |

| TIPS | 8 (9) | 5 (28) | 13 (12) | 0.028 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 10 (11) | 1 (6) | 11 (10) | 0.911 |

| History of gastrointestinal bleed | 24 (28) | 10 (56) | 34 (32) | 0.019 |

| Listed for liver transplant | 23 (26) | 3 (17) | 26 (25) | 0.395 |

Cardiovascular disease: history of myocardial infarction or stroke. HD: hemodialysis. VTE: venothromboembolism. ESLD: end stage liver disease. TIPS: transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Active malignancy: receiving treatment for malignancy or with evidence of malignancy by imaging or tumor markers. Non-active malignancy: malignancy in remission.

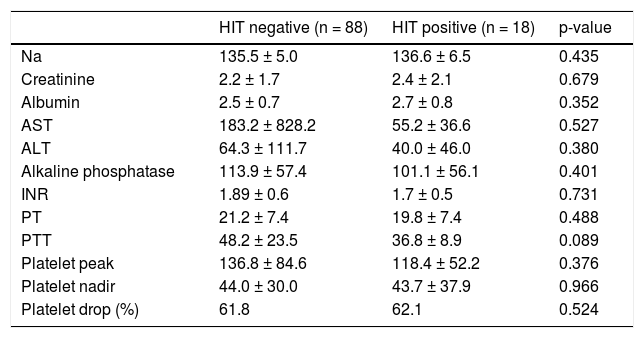

Eighteen patients in our cohort had a positive HIT Ab as defined by an OD greater than 0.40 (Figure 1). Of those who tested positive for HIT, 11 were exposed to UFH at prophylactic doses or during hemodialysis, two were exposed to LMWH, and five had no documented heparin exposure. No laboratory data were associated with HIT Ab positivity (Table 2). The platelet nadir was similar in patients testing positive and negative for HIT: 43.7 ± 37.9 for HIT positive vs. 44.0± 27.0 for HIT negative patients (p = 0.966). The mean platelet drop was 43.7% ± 37.8 in HIT antibody positive group versus 61.9% ± 22.5 in the HIT antibody negative group (p = 0.972).

Comparison of selected lab values for HIT positive vs. HIT negative patients (data collected from initial labs sent during the admission that HIT Ab was sent).

| HIT negative (n = 88) | HIT positive (n = 18) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 135.5 ± 5.0 | 136.6 ± 6.5 | 0.435 |

| Creatinine | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 0.679 |

| Albumin | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.352 |

| AST | 183.2 ± 828.2 | 55.2 ± 36.6 | 0.527 |

| ALT | 64.3 ± 111.7 | 40.0 ± 46.0 | 0.380 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 113.9 ± 57.4 | 101.1 ± 56.1 | 0.401 |

| INR | 1.89 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.731 |

| PT | 21.2 ± 7.4 | 19.8 ± 7.4 | 0.488 |

| PTT | 48.2 ± 23.5 | 36.8 ± 8.9 | 0.089 |

| Platelet peak | 136.8 ± 84.6 | 118.4 ± 52.2 | 0.376 |

| Platelet nadir | 44.0 ± 30.0 | 43.7 ± 37.9 | 0.966 |

| Platelet drop (%) | 61.8 | 62.1 | 0.524 |

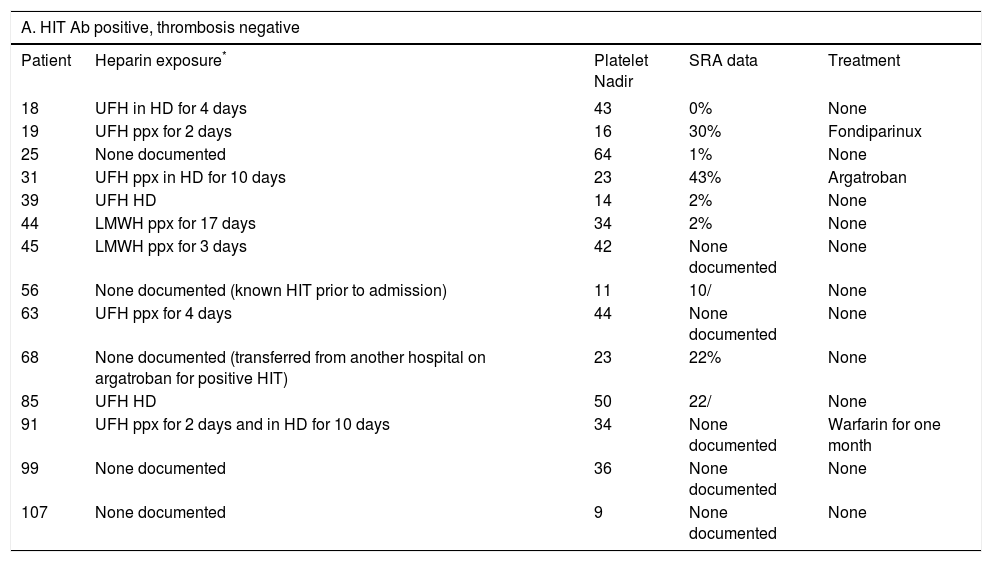

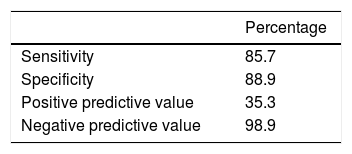

Four of the 18 (22%) seropositive HIT antibody patients had a proven thrombosis: three were found to have a documented DVT and one a documented pulmonary embolism. The platelet nadir for HIT positive patients who developed a thrombosis was 85.8 ± 62.7 vs. a platelet nadir of 30.7 ± 16.1 for HIT positive without a thrombosis (p = 0.046). The percentage platelet drop for HIT positive patients with a thrombosis was 48.7% ± 33.3 and that for HIT positive but thrombosis negative patients was 65.9% ± 22.4 (p = 0.238). The optical density for seropositive patients who developed a thrombus was 0.45 ± 0.05 vs. 0.86 ± 0.55 for seropositive HIT patients without a thrombus (p = 0.164) (Table 3). Notably, an additional eight (9.0%) patients in the cohort had a thrombus despite negative HIT antibody, six of whom were receiving heparin or LMWH prophylaxis; however there was no significant difference in rate of thrombosis development when compared to the HIT Ab positive patients (p = 0.109). Of the eighteen patients with a positive HIT Ab, twelve subsequently had an SRA confirmatory test sent. Three of four patients who tested positive for HIT and had a thrombosis had an SRA sent, with none having a positive test (as defined by an SRA > 0%). Nine of 14 patients with a positive HIT Ab without thrombosis had an SRA sent, and four of the nine had a positive test (Table 3A). One of the 88 patients with negative HIT testing has a positive SRA result. The patient had the presence of a thrombosis and was treated with warfarin therapy. Based on our definition of the diagnosis of HIT being a positive Hit Ab with a positive SRA or the presence of thrombosis, a total of 7 of the patients in this cohort had HIT. The sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values of HIT Ab testing in this cohort are shown in table 4.

Heparin exposure, platelet nadir, SRA results, development of thrombus, and treatment data for patients with a positive HIT antibody (4a: thrombosis positive, 4b: thrombosis negative).

| A. HIT Ab positive, thrombosis negative | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Heparin exposure* | Platelet Nadir | SRA data | Treatment |

| 18 | UFH in HD for 4 days | 43 | 0% | None |

| 19 | UFH ppx for 2 days | 16 | 30% | Fondiparinux |

| 25 | None documented | 64 | 1% | None |

| 31 | UFH ppx in HD for 10 days | 23 | 43% | Argatroban |

| 39 | UFH HD | 14 | 2% | None |

| 44 | LMWH ppx for 17 days | 34 | 2% | None |

| 45 | LMWH ppx for 3 days | 42 | None documented | None |

| 56 | None documented (known HIT prior to admission) | 11 | 10/ | None |

| 63 | UFH ppx for 4 days | 44 | None documented | None |

| 68 | None documented (transferred from another hospital on argatroban for positive HIT) | 23 | 22% | None |

| 85 | UFH HD | 50 | 22/ | None |

| 91 | UFH ppx for 2 days and in HD for 10 days | 34 | None documented | Warfarin for one month |

| 99 | None documented | 36 | None documented | None |

| 107 | None documented | 9 | None documented | None |

| B. HIT Ab positive, thrombosis positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Heparin exposure* | Platelet Nadir | SRA data | Thrombosis location† | Treatment |

| 6 | UFH ppx for 4 days | 56 | 0% | LE DVT | Fondiparinux initially, followed by 3 months of Coumadin |

| 36 | UFH ppx and in HD for 5 days | 22 | None documented | LE SVT | Untreated |

| 76 | UFH ppx and in HD for 2 days | 14 | 0/ | LE DVT | Untreated |

| 82 | UFH HD | 119 | 18/ | PE | 3 months coumadin |

We also found a lack of consistency in treating those patients tested positive for HIT. Of the fourteen HIT positive patients who did not develop a thrombus, only three received treatment with an alternative anticoagulant, and each received a different regimen with either warfarin, fondaparinux, or argatroban (Table 3A). Of the four patients who had thrombotic complications in the setting of a positive HIT Ab, two received treatment with three months of warfarin, while two others received no treatment (Table 3B).

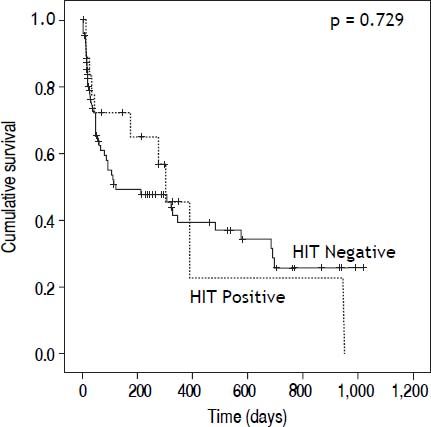

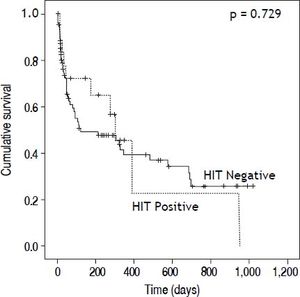

We also examined morbidity and mortality associated with HIT testing. HIT Ab positive and negative patients had similar length of hospitalization (17.2 ± 10.6 days vs. 21.6 ± 15.9 days, p = 0.266) and days to death (80.9 ± 117.9 days vs. 95 ± 117.9 days, p = 0.729) (Figure 2). Notably, only one of 18 (5.5%) HIT seropositive patients was transplanted compared to 24 of 88 (27%, p = 0.048) seronegative patients. It is not clear as to whether the positive HIT results impacted the decision to proceed with liver transplantation. In the HIT Ab positive patients, there were no differences in length of hospitalization (19.9 ± 11.3 vs. 20.3 ± 12.4; p = 0.168) or days to death (193.1 ± 138.9 vs. 329.5 vs. 420.4; p = 0.292) for patients without and with thrombosis respectively.

DiscussionOur data suggests that HIT Ab testing through available enzyme immunoassays (EIA) has low positive predictive value in patients with cirrhosis. The assay was low yield as only 17% of the total cohort were seropositive for HIT Ab, and fewer still (4/18, 22%) had a confirmed test with a positive functional serotonin release assay. The poor predictive value of the EIA for true HIT at an OD < 1.0 has been demonstrated in other patient populations.13 Our findings reinforce the high false positive rate of the EIA specific to those patients with cirrhosis. Furthermore, these results illustrate the importance of interpreting the EIA in clinical context, implementing other criteria, and not reacting to the lab isolation.11 Further prospective validation of a pretest score, such as the 4T score may have significant value in this population of patients.

In addition to demonstrating a high false-positive rate, we did not find that HIT testing in patients with cirrhosis correlated with thrombotic events. While platelet drop and OD are typically associated with development of thrombosis in HIT,14,15 we did not find such an association in our cohort. In fact, those who developed a thrombus in our cohort actually had a lower OD and higher platelet count. Additionally, eight (9%) of the patients who tested negative for HIT in our cohort developed a thrombus, adding to the growing body of evidence that cirrhotics appear to be at increased risk of thrombotic events despite lab testing that seem to indicate they are auto-anticoagulated.10,16,17 Of note, HIT testing in our cohort showed a high negative predictive value. Given the bias present in this sample and the incomplete testing of the SRA, the negative predictive value is likely falsely elevated. However, it does appear that negative testing in a cirrhotic population should be relatively reassuring. In addition the sensitivity and specificity of HIT testing is relatively high in this cohort, however, again we do expect the numbers would be lower in a prospectively defined population, consistent with what has been published in other populations of patients.

While our data indicate that HIT testing is poorly predictive of thrombus development, it does suggest that HIT testing impacts decision to transplant patients. In our cohort, only 5.5% of HIT positive patients were transplanted compared to 27% of HIT negative patients. It is unclear whether seropositivity itself precluded transplant or whether these patients were deemed too ill to undergo a transplant. However, one can speculate that a positive HIT testing at the very least complicated management, as transplant recipients who have HIT are at risk for complications (thrombocytopenia, arterial and venous thrombosis) when challenged with heparin in the post-operative period, and may be at risk for bleeding when alternative anticoagulation such as a direct thrombin inhibitor is used instead. One recent study showed the efficacy of the use of enoxaparin for long-term prophylaxis of portal vein thrombosis, which, if widely adopted, may result in increased exposure for patients with cirrhosis to heparin products.18,19

Our paper, to our knowledge, is the first of its kind in exploring HIT testing and outcomes data in patients with cirrhosis and has strength in that it was a review of a large cohort of hospitalized patients. Our study does have several limitations: as a retrospective study, there were no standardized protocols in place for patients tested with HIT, which led to inconsistencies in testing and imaging (e.g. SRA testing and testing for thombosis). Our population is also inherently biased, given it was a retrospective review of patients who had HIT testing sent. In addition, we did have a small number of patients with HIT Ab positivity, limiting our power to detect significant differences which may have resulted in a type II error. A prospective study with standardized protocols in place would better define the sensitivity and specificity of HIT testing in the population. The present study does highlight an important aspect of diagnosis and management of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis.

HIT testing is complicated in cirrhotic patients who often have thrombocytopenia at baseline, and our data suggest that HIT Ab testing is poorly predictive of clinical outcomes such as thrombosis. This study highlights the need for more refined guidelines for HIT testing and management in cirrhosis. Further development of clinical tools along with laboratory testing would greatly benefit cirrhotic patient, given their high rates of hospitalization and exposure to heparin products.15

Abbreviations- •

AB: antibody.

- •

DVT: deep vein thrombosis.

- •

HIT: heparin induced thrombocytopenia.

- •

INR: international normalized ratio.

- •

LMWH: low molecular weight heparin.

- •

OD: optical density.

- •

PE: pulmonary embolism.

- •

PF4: platelet factor 4.

- •

SRA: serotonin release assay.

- •

UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Neehar D. Parikh’s preparation of this article was supported in part by grant 5T32DK077662-04| from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (PI: Michael Abecassis, MD, MBA).