In recent years there has been a significant increase in the consumption of dietary energy supplements (DES) associated with the parallel advertising against obesity and favoring high physical performance. We present the case and outcome of a young patient who developed acute mixed liver injury (hepatocellular and cholestatic) after ingestion of various “over the counter” products to increase muscle mass and physical performance (NO Xplode®, creatine, L-carnitine, and Growth Factor ATN®). The diagnosis was based on the exclusion of other diseases and liver biopsy findings. The dietary supplement and herbal multivitamins industry is one with the highest growth rates in the market, with annual revenues amounting to billions and constantly lacking scientific or reproducible evidence about the efficacy and/or safety of the offered products. Furthermore, and contrary to popular belief, different forms of injury associated with these natural substances have been documented particularly in the liver, supporting the need of a more strict regulation.

The consumption of dietary energy supplements (DES) and “natural” products containing a long list of vitamins, antioxidants, amino acids and herbal substances has raised significantly.1 No prescription is required to obtain them, and in many cases there is not a clear cut scientific evidence of their benefits.

Teenagers and young athletes are population groups particularly prone to consume them with the intention to increase strength, muscle mass or improve physical performance.2 During the last decade the number of reports dealing with hepatotoxicity by DES or herbal products has increased, ranging from asymptomatic liver tests abnormalities to fulminant hepatitis and death.3 We report a case of acute hepa-totoxicity attributed to DES consumption.

Case ReportClinical presentationA 17-year-old heterosexual male student from Guerrero, Mexico, started in July with asthenia, weakness, anorexia, nausea and occasionally vomiting associated with epigastric pain; a week later he presented jaundice and dark urine. A general practitioner identified jaundice, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated aminotransferases and apparent hepatomegaly by ultrasound upon consultation. The patient denied recent/chronic alcohol abuse or consumption of drugs. Clinical diagnosis of acute infection probably by hepatitis A virus was assumed and ribavirin, prednisone and colchicine for 2 weeks were initiated. Later serological tests for viral hepatitis (A, B and C) were negative. Given the persistence of jaundice, pruritus, general symptoms and a 6 kg weight-loss in two months, the patient was referred to a tertiary care hospital.

Later on at our institution, he informed having consumed NO-Xplode®, Growth Factor ATN®, Simicarnitina® (two spoons as powder for milkshake two times daily plus 2 capsules of each one of the other products respectively) (Table 1) during the three consecutive months previous to symptoms onset, as part of bodybuilding training. His past medical history was only remarkable for occasional alcohol intake (beer every 2 months) and denied high-risk sexual behavior, intravenous drug use, transfusions, tattoos or piercings. Aged 14, he received ablation treatment for Wolf Parkinson White syndrome.

Ingredients of dietary energy supplements consumed.

| DES | Ingredients according to label and manufacturer |

|---|---|

| N.O.-XPLODE® | Product: Creatine 1,025 g Ingredients: vitamin B6, vitamin B9, vitamin B12, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, sucrulose, calcium, citric acid, natural and artificial flavors. Nutritional information per serving of 20.5 g: 40 Kcal, proteins 0 g, sugars 0 g, carbohydrates 7 g. Developed and manufactured for: Bio-Engineered Supplements & Nutrition-BSN, Boca Raton, FL 33487 USA. |

| Growth factor ATN® | Glutamic acid, arginine, alanine, triopano, tyrosine, cystine, lysine, isoleucine, proline, leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, valine, histidine, aspartic acid, glycine, serine, collagen. (American Team Nutrition) |

| SimiCarnitina® | Milk Whey Protein Concentrate and L-Carnitine (20 g). Developed and Manufactured: Por Un País Mejor, A.C. Independencia No. 26, Col. Independencia C.P. 03630 México, D.F., México. |

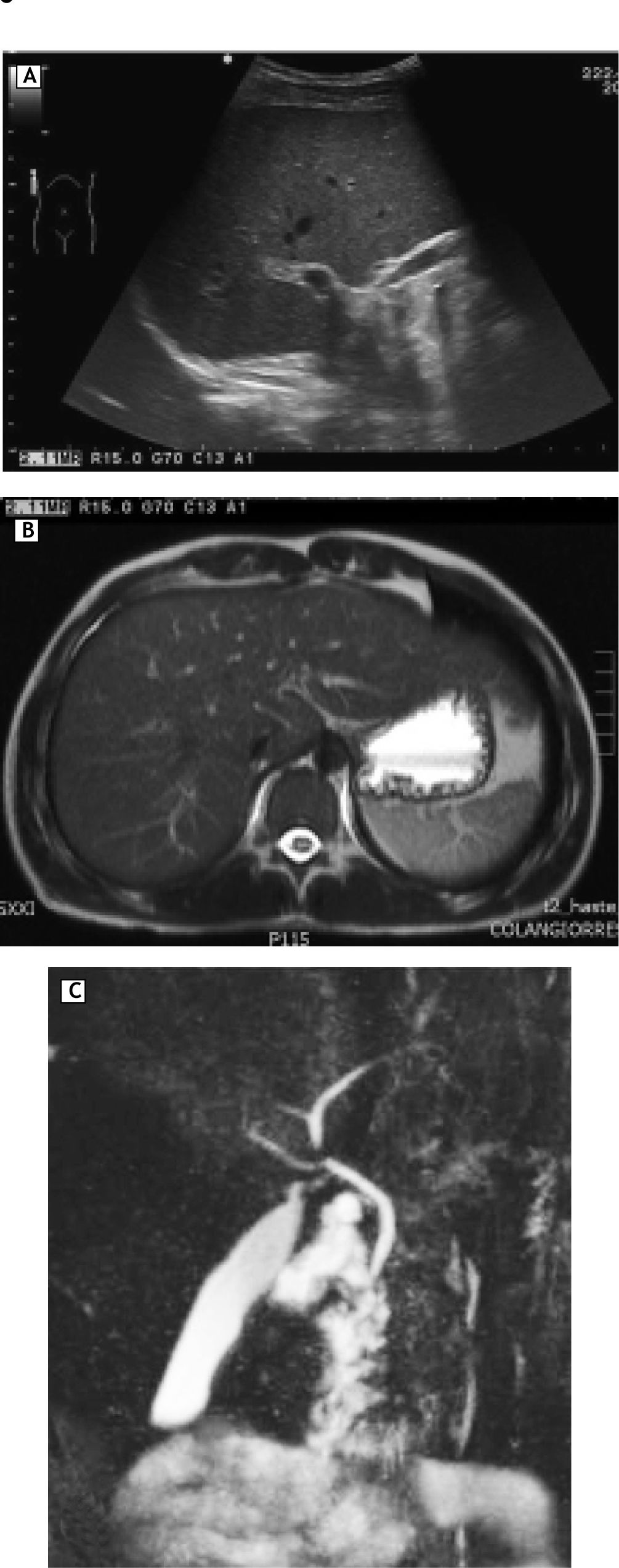

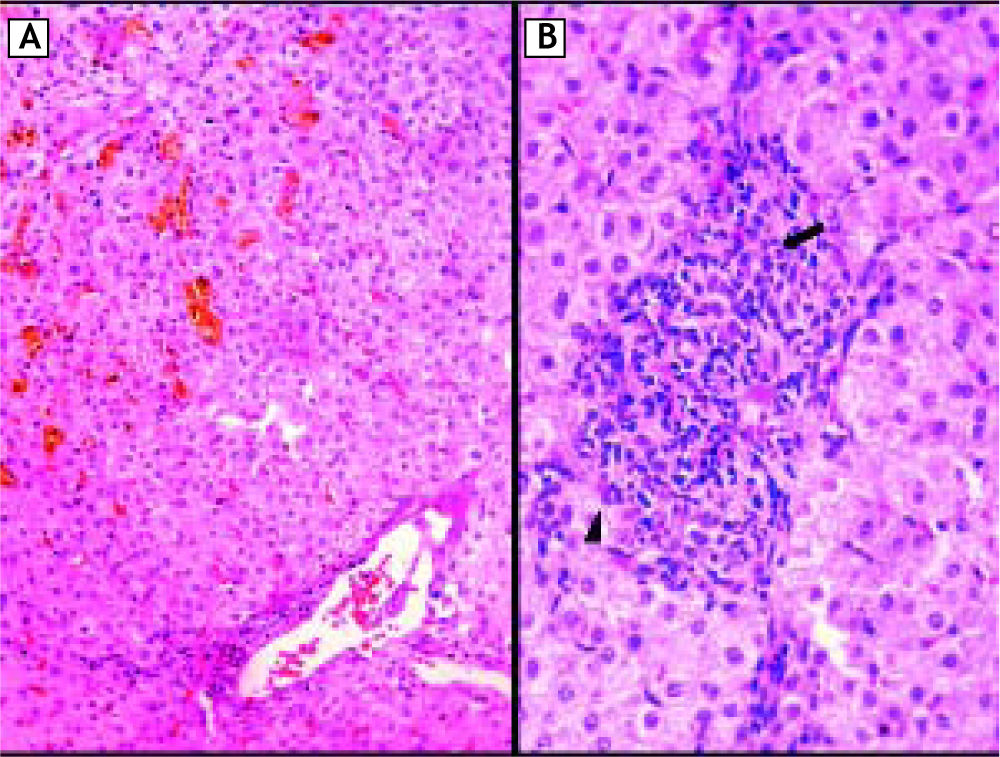

On physical examination tachycardia (120 bpm), jaundice without hepatomegaly and signs of scratching were identified. New serological tests for hepatitis A, B and C in addition to antibodies assessing autoimmune liver disease were negative; ferritin and thyroid function tests were normal (Table 2). The ultrasound showed no abnormalities in liver, gallbladder, bile ducts or intrahepatic veins (Figure 1A). Magnetic resonance cholangiography demonstrated normal appearance of extra and intrahepatic biliary system (Figure 1B and 1C). In the setting of persistent hyperbilirubinaemia, elevated ALP, ALT (more than 10 times upper normal limits) and clinical suspicious of toxic hepatitis by DES, a percutaneous liver biopsy was performed, revealing portal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with scattered eosinophils, inflammatory damage to interlobular bile duct (ILBD) epithelium, moderate ductopenia (absence of ILBD in 3 out of 8 portal tracts), marked perivenular intracytoplasmic and canalicular cholestasis in the lobule, with mild hepatocellular swelling and eventual multinucleation (Figure 2).

Evolution of Laboratory Test.

| Parameter | 13/Aug/10 | 23/Aug/10 | 26/Aug/10 | 28/Aug/10 | 29/Aug/10 | 08/Sept/10 | 29/Sept/10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB mg/dL | 17.5 | 31.46 | 21.88 | 17.98 | 13.35 | 5.0 | 1.3 |

| DB mg/dL | 10.53 | 18.07 | 12.43 | 12.03 | 10.87 | 3.7 | 0.6 |

| IB mg/dL | 7 | 13.39 | 9.45 | 5.95 | 2.48 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| AST U/L | 489 | 245 | 272 | 122 | 86 | 51 | 30 |

| ALT U/L | 640 | 260 | 245 | 70 | 103 | 62 | 40 |

| GGT U/L | 38 | 36 | - | - | 40 | 30 | - |

| ALP U/L | 850 | 1,081 | 923 | - | 336 | 227 | 125 |

| PT (sec) | - | 11 | 12 | - | 12.6 | 13 | - |

| LDH U/L | - | 455 | - | 390 | 348 | 323 | - |

| WBC (103/μL) | 17 | 17.3 | - | 12.26 | 11.72 | 10.4 | 8.0 |

| Albumin g/L | 4.2 | 4.3 | - | - | 3.6 | - | 4.0 |

| Glucose mg/dL | 91 | 110 | 128 | 85 | - | 95 | 91 |

| Hb g/dL | 11.8 | 11.9 | 12.7 | 13.5 | 13 | 12.7 | - |

| Platelets (103/μL) | 412 | 416 | 457 | 420 | 362 | 393 | - |

Bold characters express out-of-range values. TB: Total bilirubin. DB: direct bilirubin. IB: indirect bilirubin. ALT: alanine aminotransferase. AST: aspartate aminotransferase. PT: protrombine time. GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase. LDH: lactic dehydrogenase. ALP: alkaline phosphatase. WBC: white blood cells. Hb: hemoglobin.

Percutaneous liver biopsy. A. Photomicrograph of histological sections showing a portal triad (lower right) with mild lymphocytic infiltrate and minimal interface hepatitis; note the absence of bile duct. Marked perivenular intracytoplasmic-canalicular cholestasis (upper left) is evident (HE ori-ginal magnification 100x). B. High power view of a portal tract: a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate with some eosi-nophils (arrowhead); the bile duct epithelium (arrow) is disrupted by lymphocytes (HE, original magnification 400x). Special stains (PAS and Pearl, not shown) were negative for abnormal deposits.

Having ruled out some other causes of liver injury, the diagnosis of mixed acute hepatotoxicity (cholestatic and hepatocellular) secondary to DES was rendered. Treatment was initiated with cholestyramine, ursodeoxycholic acid 750 mg/day and total discontinuation of nutritional supplements. The patient was discharged with clinical and biochemical improvement after 7 days of admission. Liver tests returned to normal levels one month after therapy implementation.

DiscussionThe use of complementary and alternative medicine based on DES, herbs and vitamins has increased during recent decades with prevalence estimates from 18 to 35% in general population, being higher in athletes (47%) and cancer patients (> 53%); surveys have identified that up to 100% of bodybuilders consume nutritional supplements.4,5 In the US, people spend more than 30 million dollars annually in products intended to lose weight without a clear scientific evidence about their utility,3 even the FDA allows the distribution of supplements without verifying its safety and efficacy, becoming a multibillion dollar industry.6

In many countries there exist no regulation of these products beyond the strict security requirements of conventional drugs, nor is a program of post-marketing surveillance.7

The frequency of hepatotoxicity associated with DES have been reported between 2 and 10%.1 Some products known to be associated with liver injury are: Herbalife®, Camellia sinensis (green tea), Usnic acid, Hydroxycut, Morinda citrifolia (Noni Juice), Ma huang (Ephedra sinica), Germander, Kava, Chaparral, vitamin A and anabolic steroids among many others.6,8-12 Some pathophysiological mechanisms that explain liver damage are: drug-induced autoimmunity, apoptosis induction, hypersensitivity reactions, toxic metabolite formation, production of androgenic substances, interaction between formula ingredients, dysfunction of the bile transporters and inhibition of cytochrome P450;5,7,12,13 other result from product-container contamination with heavy metals (lead, mercury, arsenic) fungi and aflatoxins, lack of proper identification of herbal compounds, substitution of ingredients or higher content of alkaloids than indicated on the label.2,3,6

Drug hepatotoxicity is a rare event and can occur as a direct damage (usually dose dependent) or as an unpredictable idiosyncratic reaction with a latent period of 5 to 90 days. The spectrum of hepatotoxicity ranges from asymptomatic elevation of ALT’s to fulminant hepatitis.12

Garcia-Cortes, et al.1 identified 13 cases (2%) of liver damage induced by “natural remedies” from 512 cases of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) reported in the Spanish registry of liver toxicity between 1994 and 2006. Most cases were women with jaundice and hepatocellular damage. The main substances involved were Camellia sinensis (green tea), Rhamnus purshianus (cascara buckthorn), isoflavones, valerian, Cassia angustifolia and others. The main reasons for the use of these compounds were weight lose, anxiety or constipation.

The diagnosis of hepatotoxicity can only be established when other causes of liver disease are carefully excluded as there are no available biomarkers of hepatotoxicity and the metabolites of herbal products are difficult to measure.13 The gold standard for the diagnosis is the re-challenge test, not currently used because of the inherent risk, although re-exposure (often inadvertently) can provide strong circumstantial evidence.14-16

Some scales have been used to assess the causality of DILI.13,11 Teschke scale14 is based on scores from the onset time to toxicity, pattern of liver enzymes elevation (hepatocellular or cholestatic), ALT:ALP range, concomitant use of alcohol or other drugs, risk factors, viral serological tests, re-exposure and exclusion of other diseases. Finally the score qualifies the causality: ≤ 0 = excluded, 1-2 = unlikely, 3-5 = possible, 6-8 = probable, > 8 highly probable. Our patient received a score of 1 in the main test, having a probable causality (Table 3).

Teschke Main-test for hepatocellular injury and score of the current case.

| Parameter | Teschke score | Case score |

|---|---|---|

| • Time to onset from the beginning of the drug. | ||

| 5-90 days | +2 | +2 |

| < 5 or >90 | + 1 | - |

| • Time to onset from cessation of the drug. | +1 | +1 |

| • Course of ALT after cessation of the drug. | ||

| Decrease ≥ 50% within 8 days. | +3 | - |

| Decrease ≥ 50% within 30 days. | +2 | +2 |

| No information. | 0 | - |

| Decrease ≥ 50% after the 30th day. | 0 | - |

| Decrease < 50% after the 30th day or recurrent. | -2 | - |

| • Risk factor ethanol. | ||

| Yes. | +1 | - |

| No. | 0 | 0 |

| • Risk factor age. | ||

| ≥ 55 years. | +1 | - |

| < 55 years. | 0 | 0 |

| • Concomitant drug(s). | ||

| None or no information. | 0 | 0 |

| Concomitant drug with incompatible time onset. | 0 | - |

| Concomitant drug with compatible time to onset. | -1 | - |

| Concomitant drug know as hepatotoxin and compatible time to onset. | -2 | - |

| Concomitant drug with evidence for its role in case (positive rechallenge test). | -3 | - |

| • Search for non drug causes. | ||

| Group I and group II.* | ||

| All causes-groups I and II-reasonably ruled out. | +2 | +2 |

| The six causes of group I ruled out | +1 | - |

| Five or four causes of group I ruled out. | 0 | - |

| Less than four causes of group I ruled out. | -2 | - |

| Non drug cause highly probable. | -3 | - |

| • Previous information on hepatotoxicity of the drug. | ||

| Reaction labeled in the product characteristics. | +2 | - |

| Reaction published but unlabelled. | +1 | - |

| Reaction unknown. | 0 | 0 |

| • Response to readministration. | ||

| Doubling of ALT with drug alone. | +3 | - |

| Doubling of ALT with the drugs already given. | +1 | - |

| Increase of ALT but less than Nl in the same conditions as for first administration. | -2 | - |

| Other situations. | 0 | 0 |

| • Total score for the patient. | 7 points |

From Teschke R. Ann Hepatol 2009; 8(3): 184-95 (reference 14). *Group I: anti-HAV-IgM, anti-HBc-IgM/HBV-DNA, anti-HCV-IgM/HCV-RNA, hepatobiliary sonography/color Doppler sonography of liver vessel, alcoholism (AST/ALT ≥ 2), Acute recent hypotension history. Group II: complications of underlying disease(s), infection suggested by PCR and titer change for: cytomegalovirus, Epstein Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus.

In the case we presented, patient took three different DES based primarily on multiple amino acids, creatine, minerals and/or multivitamins: NOXplode®, Growth Factor ATN®, Simicarnitina®. We could not identify which of the ingredients was the cause of hepatotoxicity. It has been postulated that the benefit of amino acids in energy production resides in increasing protein synthesis, release growth hormone and/or nitric oxide production, although no studies have demonstrated its effect on physical performance or increase in muscle strength.4,5 The trouble with amino acids supplements is its use in non-physiological mega-doses or in people with comorbidities.18 NO-Xplode® that contains arginine a-ketoglutarate, caffeine, minerals, creatine and other amino acids has also been associated with ischemic colitis, cardiovascular symptoms such as palpitations, tachycardia, syncope, vertigo and vomiting.19,20

It is noteworthy in this case the discrepancy between the findings of raised ALP with normal levels of GGT. Clinically, we try to discard causes of isolated elevation of ALP from any source other than the liver (especially bone disease). There are some uncommon liver diseases of infancy that could present with normal or low GGT levels and include idiopathic neonatal hepatitis, arthrogryposis-renal dysfunction-cholestasis syndrome and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC type 1 and 2) but these abnormalities commonly appear in the first months of life with rapid onset of liver failure within the first few years. The cause of this discrepancy is unknown but defects in hepatocellular canalicular ATP-dependent transport system or heterozygosity for the bile salt export pump gene or suppressed GGT expression has been postulated.21,22

The regulation of dietary supplements in Mexico published in 2010 establishes the minimum requirements in the process of preparing dietary supplements to prevent contamination.23 The General Health Law provides fines for marketing herbal remedies or dietary supplements promoted with therapeutic properties or false advertisings without scientific basis or sanitary registry.24,25 The Federal Commission for Protection Against Health Risks (COFEPRIS) issued a warning in 2009 about the sales of more than 22,000 DES, finding 15 “miracle products” used primarily for weight loosing that contained toxic herbs, representing a potential health risk.26

The main problem, as in the presented case, is that young people or athletes commonly take multiple doses and combinations of DES above tolerable or accepted levels. This case emphasizes the need to suspect and investigate the potential contribution of DES or herbal remedies in any patient with elevated liver enzymes, jaundice and/or cholestasis. In addition, stricter rules are needed for the authorization, sale and advertising of these products.

Abbreviations- •

DES: dietary energy supplements.

- •

ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

- •

ALP: alkaline phosphatase.

- •

DILI: drug-induced liver injury.

- •

GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Giovanni Avelar-Escobar, Jorge Méndez-Navarro, Nayeli X. Ortiz-Olvera, Guillermo Castellanos, Roberto Ramos, Víctor E. Gallardo-Cabrera, José de Jesús Vargas-Alemán, Óscar Díaz de León, Elda V. Rodríguez and Margarita Dehesa-Violante have nothing to disclose.