Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a known contributor to non-hepatic cancers (NHC). We aimed to describe the incidence and predictors of NHC in patients with ALD.

Materials and methodsThe WALDO study is a multicenter cohort study of patients with histologically characterized ALD. Participants are followed from the time of liver biopsy and outcomes are captured from health records. The primary outcome was the incidence of the first NHC. Risk factors for NHC were presented as unadjusted and adjusted sub-distribution hazards (SDH) based on competing risk analysis. Statistical analyses were done in R.

Results691 patients were included. The median age was 51 years (IQR 43- 59), 427 (62 %) patients were male and 406 (59 %) had cirrhosis on biopsy. During a median follow-up of 4.7 years (IQR 1.2–9.5 years), 76 patients (11 %) with ALD developed NHC. The cumulative incidence of NHC in ALD was 2.4 % (1.4–3.9 %) over five years. The most common NHC was respiratory (18 cases, 23 % of NHC) followed by digestive tract (17 cases, 22 %) and cancers of the head and neck (13 cases, 17 %). On multivariable analysis, increasing age (SDH 1.04; CI 1.01-1.06; p = 0.011), previous smoking (SDH 3.65, CI 1.44-9.65; p = 0.006) and current smoking (SDH 3.14; CI 1.27-7.74; p = 0.013) were associated with a higher risk of NHC.

ConclusionNHC is common and frequently fatal. However, NHC is an infrequent cause of morbidity or mortality in ALD compared to liver-related outcomes.

Alcohol-related Liver Disease (ALD) accounts for nearly half of cirrhosis-associated deaths in the United States (US) and the world [1,2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) attributes 3 million deaths (5.3 % of all mortality) annually worldwide as a result from the harmful use of alcohol [3]. ALD is a disease with a spectrum, including simple steatosis, alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) and cirrhosis, caused by excessive alcohol intake [4]. The most effective intervention to treat ALD remains prolonged alcohol abstinence [5]. Alcohol has also long been established to be a predisposing factor to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounting for 30 % of cases and HCC-specific deaths worldwide [6,7].

In addition to HCC, there is a causal link demonstrated between alcohol consumption and cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, esophagus, liver, breast, colon, and rectum with multiple pathogenic pathways suggested, such as genetic polymorphism for dehydrogenases and production of reactive oxygen species [8,9]. In general, cirrhosis is an independent two-fold risk factor for non-hepatic cancers (NHC) compared to those without cirrhosis [10]. Recently, an estimation study proposed that approximately 1.7 % of all new cancer cases could be traced back to harmful consumption of alcohol [11]. Furthermore, a population-based cohort study from Sweden found a 19 % increased risk of NHC in ALD in those surviving over one year, however, the study was limited in demographic variables such as smoking and obesity, which are both known to cause an increased risk of cancer [12]. Thus, we embarked on a global initiative where we gathered and analyzed baseline and follow-up data from patients with histologically characterized ALD, termed The Worldwide Alcoholic Liver Disease Outcome (WALDO) study. Our primary aim is to identify the incidence of NHC and our secondary aim is to identify the risk factors associated with NHCs in those with histologically characterized ALD.

2Materials and methods2.1Study populationThis is an analysis of the WALDO study, a multi-centre international retrospective cohort study of patients with histologically characterized ALD from April 2002 – December 2018. The cohort is derived from 10 multiple academic centres. 7 centres were in Europe (6 U.K, 1 Sweden), 2 centres in North America (1 each in Canada and United States of America) and 1 centre in South America (Chile). Data was collected using a standardized Excel sheet distributed to each site for operators to utilize for data collection. Patients identified from local databases had baseline and outcome data manually collected retrospectively from electronic health records. Inclusion criteria included age 18 years or older with a liver biopsy demonstrating ALD. Biopsies were not centrally read. ALD is defined as a spectrum of liver disease related to alcohol use. This includes alcohol-associated hepatitis, alcohol-associated fibrosis, and alcohol-related cirrhosis. Exclusion criteria were biochemical, serologic or histologic evidence of diseases other than ALD such as metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, celiac disease, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B, and autoimmune diseases such as Autoimmune hepatitis, Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Those with proven or likely metastases to the liver were also excluded. Patients with cancer at baseline were included but the existing malignancy was not noted as an outcome event. Patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were included in the analysis but HCC was not included as a primary outcome.

2.2Data extractionThis data was sourced from electronic medical records and included, but not limited to, the following variables: age at diagnosis, gender, BMI at diagnosis, histological presentations at diagnosis as per the reading pathologist at the site, baseline comorbidities, tobacco use (categorized as non-smoker, past-smoker, and current smoker), alcohol use (discrete variable, with g/day consumption recorded by sites), biochemistry parameters at diagnosis. Variables retrieved from the EMR databases focused on survival, cause of death, cancer outcomes (hepatic and non-hepatic) and the timing of liver transplantation.

2.3OutcomesThe primary outcome was the incidence of NHC in histologically characterized ALD. The secondary outcomes were risk factors that were associated with the development of NHC. NHCs were enumerated, and each patient’s cancer type was extracted and documented in each center’s database. NHCs were defined as primary cancers not originating in the liver.

2.4Statistical analysisDemographic and clinical characteristics were reported as percentages for categorical variables, or medians and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables for the entire cohort and the NHC subgroup. The incidence rate of NHC in the follow-up period was calculated per 1000 person-years. Univariate analysis of baseline risk factors for NHCs was performed using Fine and Gray regression models to consider competing risks of non-NHC death during follow-up. Analyses were adjusted for potential confounders including, age, co-morbidities, smoking status, alcohol consumption, cirrhosis and BMI. As a sensitivity analysis, these regressions were repeated using Cox proportional hazards regression models disregarding death and liver transplantation as competing risks. The level of statistical significance was cut off at p ≤ 0.05 and all p-values are two-tailed. Statistical analysis was performed in R using the survival and cmprsk packages.

2.5Ethical statementThe WALDO study was reviewed and approved by a research ethics committee in the UK (London Bridge Research Ethics Committee, reference 18/LO/2132) as the central coordinating center is in the UK, and each contributing center sought local approval before contributing anonymized data. Individual patient consent was not sought as only routinely collected healthcare data were recorded without additional research activity and data were fully anonymized before being added to the overall database.

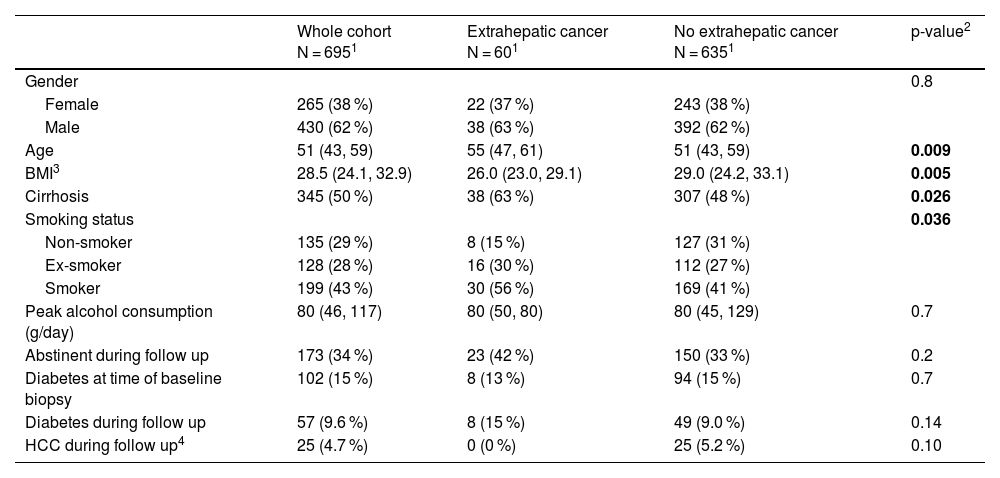

3Results691 patients with biopsy-proven ALD met our inclusion criteria. The baseline characteristics of included patients are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were male (428, 62 %) with a median age of 51 years (IQR 43-59) at the time of biopsy. Cirrhosis was present in the majority of participants (406, 59 %). Peak median alcohol consumption at the time of biopsy was 80 g/day (40-114) and during follow-up, 191 (38 %) patients were not recorded as consuming alcohol at any point and were considered to be abstinent. During a median follow-up of 4.7 years (IQR 1.2 – 9.5), 76 patients (11 %) were diagnosed with NHC, 363 (52 %) patients died or underwent liver transplantation without experiencing NHC, and 252 (36 %) patients were alive without undergoing liver transplant or developing NHC.

Baseline characteristics of WALDO cohort.

| Whole cohort N = 6951 | Extrahepatic cancer N = 601 | No extrahepatic cancer N = 6351 | p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.8 | |||

| Female | 265 (38 %) | 22 (37 %) | 243 (38 %) | |

| Male | 430 (62 %) | 38 (63 %) | 392 (62 %) | |

| Age | 51 (43, 59) | 55 (47, 61) | 51 (43, 59) | 0.009 |

| BMI3 | 28.5 (24.1, 32.9) | 26.0 (23.0, 29.1) | 29.0 (24.2, 33.1) | 0.005 |

| Cirrhosis | 345 (50 %) | 38 (63 %) | 307 (48 %) | 0.026 |

| Smoking status | 0.036 | |||

| Non-smoker | 135 (29 %) | 8 (15 %) | 127 (31 %) | |

| Ex-smoker | 128 (28 %) | 16 (30 %) | 112 (27 %) | |

| Smoker | 199 (43 %) | 30 (56 %) | 169 (41 %) | |

| Peak alcohol consumption (g/day) | 80 (46, 117) | 80 (50, 80) | 80 (45, 129) | 0.7 |

| Abstinent during follow up | 173 (34 %) | 23 (42 %) | 150 (33 %) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes at time of baseline biopsy | 102 (15 %) | 8 (13 %) | 94 (15 %) | 0.7 |

| Diabetes during follow up | 57 (9.6 %) | 8 (15 %) | 49 (9.0 %) | 0.14 |

| HCC during follow up4 | 25 (4.7 %) | 0 (0 %) | 25 (5.2 %) | 0.10 |

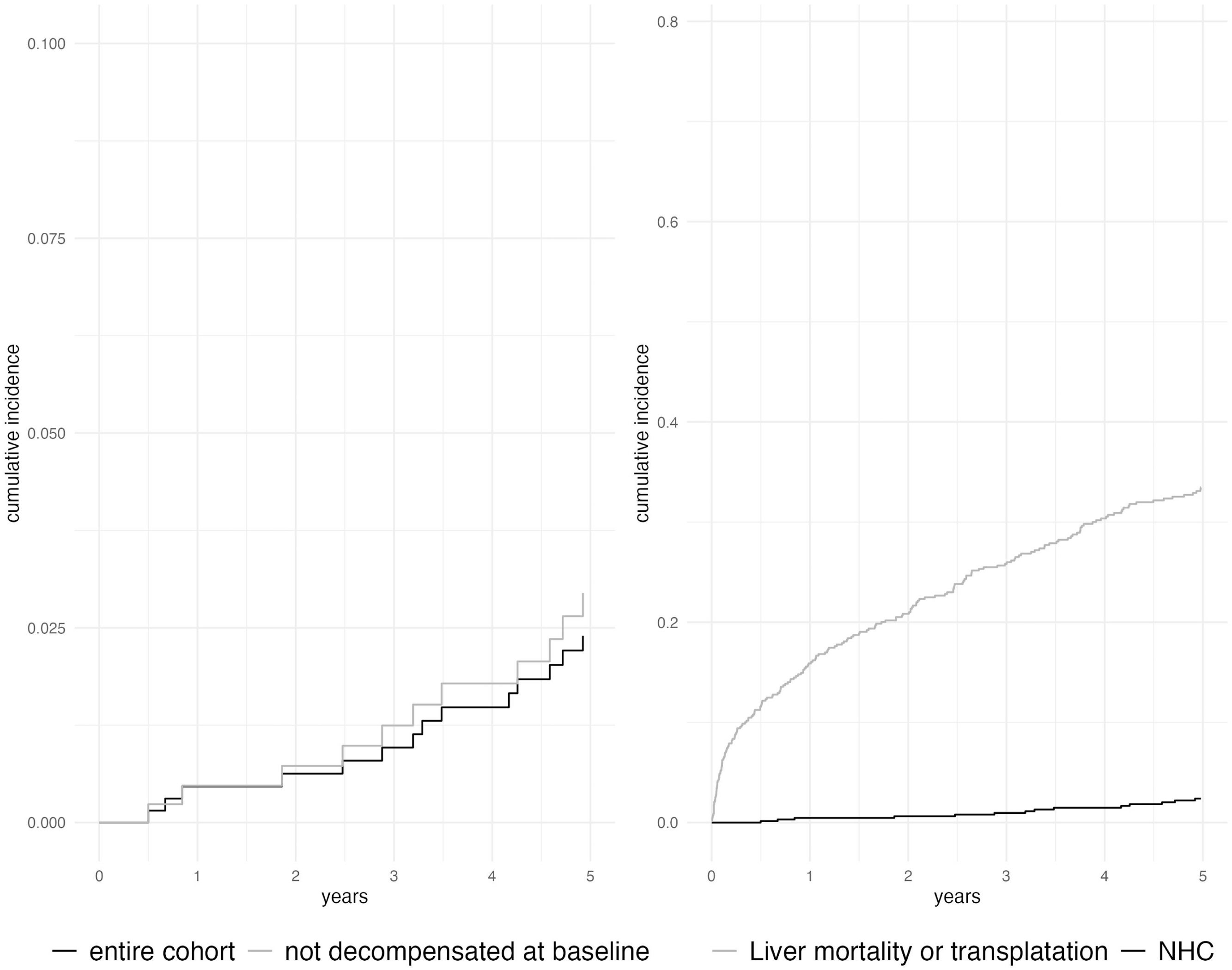

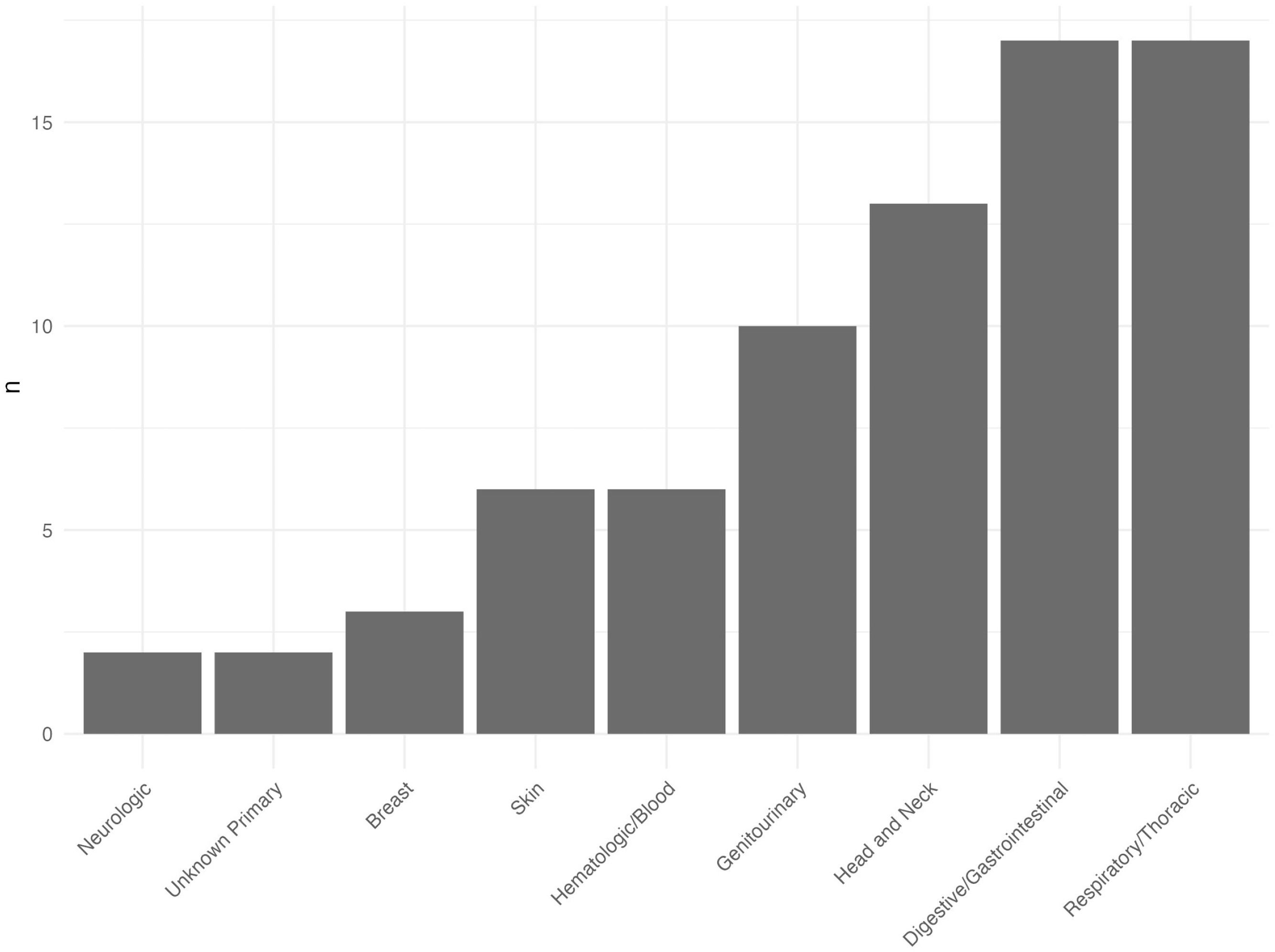

The time from index liver biopsy to diagnosis of NHC varied widely: the median delay was 10 years, with a significant variation (IQR 0.5–26.7 years). The cumulative incidence of NHC in ALD was 0.5 % (95 % CI 0.1–1.3 %) at one year after index biopsy, 2.4 % (1.4–3.9 %) at five years and 7.4 % (5.3 %–9.9 %) at ten years (Fig. 2). In comparison, twenty-five patients (3.6 %) developed HCC during follow-up with a cumulative incidence rate of 0.16 % (0.02–0.85 %) at one year, 1.8 % (0.9 %–3.3 %) at five years and 3.6 % (2.1–5.6 %) at ten years (Fig. 1). No patients developed both NHC and HCC. When patients with decompensated liver disease at baseline were excluded from analysis, the cumulative incidence of NHC was slightly higher: 0.47 % (0.1–1.6 %) at one year, 2.9 % (1.6–5.1 %) at five years and 9.1 % (6.2–13 %) at ten years after index biopsy. The site of NHC was most commonly respiratory or digestive tract: 17 (22 %) patients developed cancers at these sites. Head and neck cancer was seen in 13 (17 %) patients. The type and incidence of NHCs are depicted in Fig. 2.

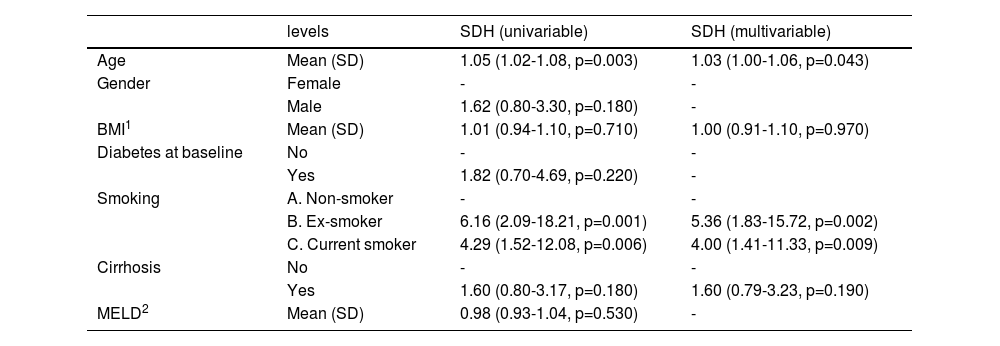

The mean age at the time of incident NHC was 67 years (IQR 59 - 72), and 48 (63 %) patients with NHC were male. The majority of those who developed NHC had exposure to tobacco: 49 % were current smokers at the time of biopsy and 34 % were ex-smokers. In univariable analysis, age (HR: 1.04; CI 1.01–1.07; p = 0.020), smoking history (ex-smoker HR: 4.18; 1.54–11.35, p = 0.005, current smoker HR: 4.45, 1.73–11.5, p = 0.002) and presence of cirrhosis (HR: 2.15; CI: 1.13-4.12; p = 0.020) increased the risk of developing NHC. On multivariable analysis, increasing age (HR=1.03; CI 1.01-1.07, p = 0.037), past smoking status (HR 5.11, CI 1.91 – 13.66; p = 0.001) and current smoking status (HR 3.84; CI 1.50 – 9.84, p = 0.005) and presence of cirrhosis (SDH 1.10; 1.10 – 4.13, p = 0.024) were associated with higher rates of NHC (Table 2). Gender, diabetes, peak alcohol consumption and presence or severity of cirrhosis were not statistically associated with NHC.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for NHC using a competing risk model (Fine-Gray regression).

| levels | SDH (univariable) | SDH (multivariable) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean (SD) | 1.05 (1.02-1.08, p=0.003) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06, p=0.043) |

| Gender | Female | - | - |

| Male | 1.62 (0.80-3.30, p=0.180) | - | |

| BMI1 | Mean (SD) | 1.01 (0.94-1.10, p=0.710) | 1.00 (0.91-1.10, p=0.970) |

| Diabetes at baseline | No | - | - |

| Yes | 1.82 (0.70-4.69, p=0.220) | - | |

| Smoking | A. Non-smoker | - | - |

| B. Ex-smoker | 6.16 (2.09-18.21, p=0.001) | 5.36 (1.83-15.72, p=0.002) | |

| C. Current smoker | 4.29 (1.52-12.08, p=0.006) | 4.00 (1.41-11.33, p=0.009) | |

| Cirrhosis | No | - | - |

| Yes | 1.60 (0.80-3.17, p=0.180) | 1.60 (0.79-3.23, p=0.190) | |

| MELD2 | Mean (SD) | 0.98 (0.93-1.04, p=0.530) | - |

• BMI: body mass index.

• MELD: model for end stage liver disease.

Fifty-nine patients (78 %) died after a diagnosis of NHC after a median of 2.0 years (IQR 0.1 – 5.2 years). This is 78 % of patients with NHC, and 8.5 % of the entire cohort. The main cause of death in patients with NHC was cancer (37 deaths, 63 % of all deaths after a diagnosis of NHC). Ten patients died from liver disease (17 % of deaths in this group). In contrast, when considering the entire cohort, deaths due to liver disease occurred in 140 patients (20 %) and a further 45 (6.5 %) underwent liver transplantation (Fig. 1b).

4DiscussionIn this multi-center international cohort of histologically characterized ALD, the incidence of NHC was considerably higher than HCC. The most common NHC was lung cancer and colorectal cancers, followed by cancers of the head and neck. The risk factors most associated with an increased risk of NHC were current and former smoker status.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer deems alcoholic beverages carcinogenic to humans but continue to be consumed around the world and is imbedded in various cultures posing a significant threat to those with concomitant liver disease. Based on a population of 7.8 billion and a reported estimated 19.3 million incident cancers worldwide, the international cancer incidence was 0.25 %/year in 2020. When accounting for hepatic cancers, the incidence of NHC worldwide in 2020 was 0.24 %/year [13]. The incidence of digestive tract, lung, and head and neck cancer in our cohort was 22 %, 22 %, and 17 %, respectively, over a median follow-up of 4.7 years. This highlights the importance of alcohol cessation in those with ALD, and possibly in those with chronic liver diseases of other etiologies. With this, it is prudent to provide timely alcohol cessation education and substance abuse resources [14].

Approximately 80 % of individuals who have an alcohol use disorder are also smokers and we identified individuals with former or current status of smoking had a higher risk of developing NHC in those with ALD [12,15]. Smoking is associated with the introduction of nitrosamines and other carcinogenic substances into the body through the respiratory system and may result in DNA alteration and/or inflammatory changes [16]. Furthermore, smoking is associated with increased mortality, independent of abstinence, with a mortality rate of 17 % and 43 % in smokers and nonsmokers aged >55. (19) Given the association of NHC with former and current smoking status, smoking cessation with patient education, non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic means is recommended to reduce the overall risk of NHC development as these are modifiable risk factors. However, it is currently unclear whether this belongs in the realm of care of the hepatologist or primary care provider, or both.

The strength of our study includes objective measures of analysis in the determination of ALD along with the multicenter collaboration representing a diverse group of patients. However, our study is not without limitations. Our data was limited by data completeness in specific categories. This may be due to a lack of available data due to a lack of biochemical analysis at the time of care of the patient and/or lack of charting at the point of care or omission. Also, our median follow-up duration was 4.7 years, and although it is a significant follow-up, it may affect the true incidence of hepatic and NHC given the slow-progressing nature of the disease. There also could be an increasing number of NHCs reported in the patients we identified in the years following our data sampling and analysis. If this is true, this would further support the importance of alcohol cessation, not only for the reduction of liver disease and its complications but also for NHC development risk.

5ConclusionsPatients with biopsy-confirmed ALD are at an increased risk of NHCs. Along with alcohol cessation, patients should be counselled and supported in the goal of smoking cessation as this would improve morbidity and mortality.

Author contributionsMayur Brahmania, Zaid Hindia, Nancy Shia, Juan Pablo Araba, Neil Rajoriyad, Guruprasad P. Aithalf, Michael Allisong, Hannes Hagström, Alisa Likhitsup, Anne McCunek, Steven Masson, Ewan Forrrest, Karin Oien, Beth Reed, Richard Parker (on behalf of the WALDO investigators)

Uncited reference[17]

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.