Autoimmune liver diseases (AILDs): autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) have different survival outcomes after liver transplant (LT). Outcomes are influenced by factors including disease burden, medical comorbidities, and socioeconomic variables.

Materials and MethodsUsing the United Network for Organ Sharing database (UNOS), we identified 13,702 patients with AILDs listed for LT between 2002 and 2021. Outcomes of interest were waitlist removal, post-LT patient survival, and post- LT graft survival. A stepwise multivariate analysis was performed adjusting for transplant recipient gender, race, diabetes mellitus, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, and additional social determinants including the presence of education, reliance on public insurance, working for income, and U.S. citizenship status.

ResultsLack of college education and having public insurance increased the risk of waitlist removal (HR, 1.13; 95 % CI, 1.05–1.23, and HR, 1.09; 95 % CI, 1.00–1.18; respectively), and negatively influenced post-LT patient survival (HR, 1.16; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.26, and HR, 1.15; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.25; respectively) and graft survival (HR, 1.13; 95 % CI, 1.05–1.23, and HR, 1.15; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.25; respectively). Not working for income proved to have the greatest detrimental impact on both patient survival (HR, 1.41; 95 % CI, 1.24–1.6) and graft survival (HR, 1.21; 95 % CI, 1.09–1.35).

ConclusionsOur study highlights that lack of college education and public insurance have a detrimental impact on waitlist mortality, patient survival, and graft survival. Not working for income negatively affects post-LT survival outcomes. Not having U.S. citizenship does not affect survival outcomes in AILDs patients.

Autoimmune liver diseases (AILDs) are chronic inflammatory disorders that affect the hepatobiliary system. AILDs include three distinct entities: primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). These disorders account for a small minority of liver transplants (LT) performed in the United States at around 3–5 %, with alcoholic liver disease (32 %) and hepatitis C (12 %) being the more common indications [1,2].

Survival of patients who undergo LT is influenced by a multitude of factors, including disease burden and medical comorbidities of both the donor and recipient. It can be challenging to differentiate the impact of these variables from socioeconomic status factors [3]. Understanding health disparities and their effects on chronic liver disease is fundamental to improving liver health outcomes.

Several studies have shown that certain social determinants of health have an influence on waitlist mortality amongst patients with AILD listed for LT [4,5]. Limited and sometimes conflicting data is available regarding the impact on post-LT patient and graft survival amongst patients with AILDs. A previous single‐ center retrospective trial between 2000 and 2011 of 204 Hispanic and non‐Hispanic patients with PBC showed no differences in mortality between both cohorts despite the greater severity of PBC among Hispanic patients [6]. However, Black and Hispanic patients with AILD had worse post-transplant mortality, according to data from UNOS [6,7]. It is unclear if these findings are due to the underlying AILD itself, as these two racial groups have higher waitlist mortality across most causes of cirrhosis.

A study of 449 patients with PSC between 1988 and 2019 (404 White and 45 Black individuals) showed higher mortality from liver‐related etiologies in Black compared to White patients (HR, 1.80; 95 % CI, 1.25–2.61) despite similar disease severity. When considering post-LT outcomes, Black patients and individuals with public insurance have been found to have poor survival when compared to white or Hispanic patients and those with private insurance, respectively [7].

The goal of policies that govern the LT process is to ensure the distribution of organs to individuals with the most significant medical need; however, disparities in many factors affect the allocation, waitlist mortality, and post-transplant outcomes. This supports the need to study the contemporary trends of these factors in greater detail [8]. We sought to analyze the impact of socioeconomic factors on AILD patients post-LT, focusing on graft and patient survival.

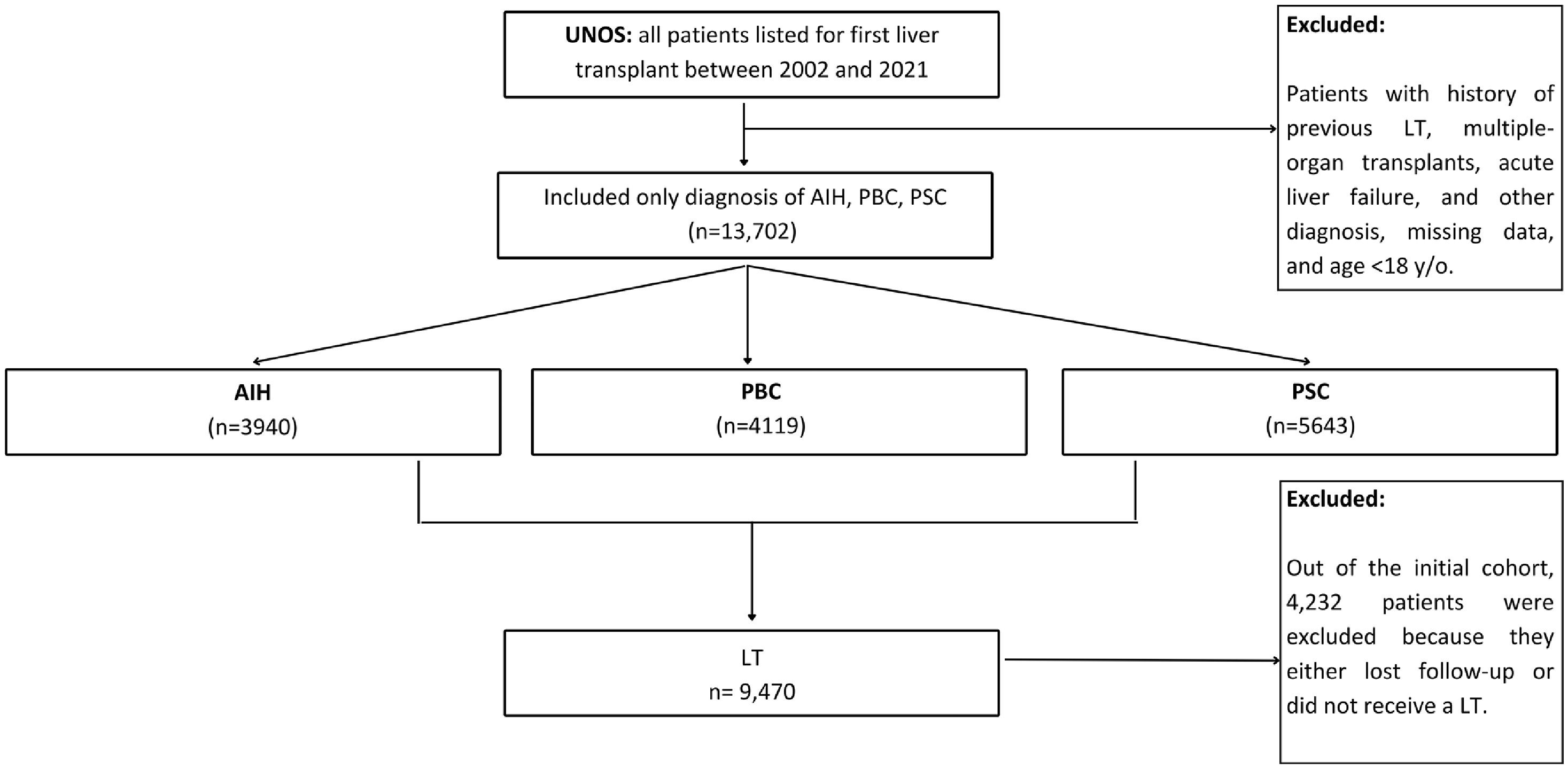

2Materials and Methods2.1Study populationWe conducted a retrospective cohort study using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database to identify adult patients (≥18 years) listed for liver transplant (LT) due to AIH, PBC, and PSC from February 27, 2002, to December 31, 2021. Patients with history of previous LT, multiple-organ transplants, or acute liver failure were excluded. We classified patients according to the etiology of liver disease as AIH, PBC, or PSC (Fig. 1). The study data were provided by the UNOS as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The authors are solely responsible for the interpretation and reporting of these data, and the views expressed in this study do not represent the official policy of OPTN or the US Government. Given that, UNOS is a publicly available deidentified patient-level database, institutional review board approval was not required according to the policies of the UNOS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

2.2OutcomeThe primary outcome was waitlist survival, defined as the composite outcome of death or removal for clinical deterioration (UNOS removal codes 5, 8, and 13). The secondary outcomes were analyzing patient and graft survival in the subgroup of patients who received liver transplant.

Patient survival after a liver transplant was defined as the length of time between the date of the transplant and the death of the recipient, or the time lost to follow-up. The post-transplant graft survival was defined as the length of time between the transplant date and either graft failure or the need for a re-LT. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to compare waitlist, graft, and patient survival between patients with AIH, PBC, and PSC as the etiology of liver disease.

2.3Study variablesPatient characteristics were compared between etiologies of liver disease. Recipient and donor characteristics differed and were analyzed separately. A larger number of variables was considered for the recipient sub cohort, including age at the time of listing, gender, self-reported race/ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), blood type, MELD score at the time of transplant, history of diabetes mellitus (DM), UNOS regions, education, insurance, income and citizenship. Within the donor variables, we included gender, blood type, and age at the time of transplant.

2.4Statistical analysisWe stratified clinical and demographic characteristics by etiology of liver disease and compared cohort characteristics using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2) for categorical variables. Continuous variables were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were summarized using percentages.

To identify significant predictors of survival, we conducted forward stepwise multi-variate Cox regression analyses, which were adjusted for both recipient and donor characteristics. We included variables that were statistically significant at the bivariate level (partial regression (0.1) and partial elimination (0.05)) or were known to be clinically relevant, such as recipient age at the time of transplant, gender, race, diabetes mellitus, and the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score at the time of listing. Additionally, we considered the donor's age, gender and blood type as factors in our analysis. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs), and statistical significance was defined as α = 0.05, with AIH patients as a reference group. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

2.5Ethical statementsInstitutional review board (IRB) approval was not required, as UNOS contains publicly available de-identified data.

3ResultsOur study identified a total of 13,702 patients diagnosed with autoimmune liver diseases who were listed for LT between 2002 and 2021. The cohort characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of the population was Caucasian, with female predominance among the AIH and PBC groups. Age was comparable among the three groups. The median MELD score at listing was higher in the AIH group than the PBC and PSC groups (18, 16, and 15, respectively). Patients who received LT had higher median MELD score values at the time of transplant (22, 22, and 20, respectively). The AIH group had a higher median BMI than the PBC and PSC groups (28, 26 and 25, respectively) and was significantly more likely to have diabetes (22 %, 17 %, and 11 %, respectively). In terms of the distribution of socioeconomic variables, the PSC group had a higher likelihood of having attained higher education, possessing private insurance, and being employed for income as compared to the AIH and PBC groups. On the other hand, citizenship status was similar across all three groups.

Cohort characteristics (n = 13,702).

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing; US, United States; IQR, interquartile range.

Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2) for categorical variables. Continuous variables were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were summarized using percentages.

Our findings on univariate analysis (Table 2) demonstrate that when compared to the AIH group (established as the reference group), the PBC group had a higher risk of waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration (HR, 1.24; 95 % CI, 1.14– 1.37; p < 0.001), while the PSC group did not show an increased risk of waitlist removal (HR, 0.64; 95 % CI, 0.58–0.71; p < 0.001). Among the socioeconomic variables included in the study, Hispanic race (HR, 1.25; 95 % CI, 1.13–1.40; p = 0.000), lack of college education (HR, 1.35; 95 % CI, 1.25–1.45; p = 0.000), public insurance (HR, 1.32; 95 % CI, 1.22–1.43; p = 0.000), non-US citizenship (HR, 1.26; 95 % CI, 1.07–1.50; p = 0.007), and not working for income (HR, 1.55; 95 % CI, 1.41–1.70; p = 0.000) were all significantly associated with an increased risk of waitlist removal.

Cox proportional‐hazards regression model of predictors of waitlist mortality.

CI, confidence interval; AIH, Autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, Primary Biliary Cholangitis; PSC, Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; AA, African American; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; US, United States.

In the stepwise multivariate analyses the PBC group (HR, 1.49; 95 % CI, 1.37– 1.63; p = 0.000) had an increased risk of waitlist removal compared to AIH. Age had a detrimental effect on waitlist removal (HR, 1.03; 95 % CI, 1.02– 1.03; p = 0.000). Black/African American race showed improved patient survival compared to White race (HR, 1.20; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.36; p = 0.000). Among the socioeconomic variables, no college education (HR, 1.13; 95 % CI, 1.05–1.23; p = 0.002) and relying on public insurance (HR, 1.09; 95 % CI, 1.00–1.18; p = 0.043) had a detrimental impact on the risk of being removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration.

3.2Patient and graft survivalFrom the initial cohort, 9470 patients received a LT. Our findings on the univariate analysis demonstrate that PSC was associated with improved survival relative to AIH (HR, 0.76; 95 % CI, 0.69–0.84; p = 0.000) (Table 3). Among the socioeconomic variables included in the study, Black/African-American race (HR, 1.11: 95 % CI, 0.99–1.25; p = 0.082), no-college education (HR, 1.28; 95 % CI, 1.17–1.39; p = 0.000), public insurance (HR, 1.43; 95 % CI, 1.31–1.56; p = 0.000), and no income (HR, 1.66; 95 % CI, 1.48–1.88; p = 0.000) were all associated with and increased risk of post-transplant mortality.

Cox proportional‐hazards regression model of predictors of patient survival.

CI, confidence interval; AIH, Autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, Primary Biliary Cholangitis; PSC, Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; AA, African American; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; US, United States.

Post-transplant patient survival rates at 5 and 10 years for those working for income (88.9 %, and 79.3 %, respectively; p = 0.000) were significantly better than those with no income (81.3 %, and 69.6 %, respectively; p = 0.000). Similarly, our analysis revealed that among those with private insurance, there was post-transplant patient survival benefit at both 5 and 10 years (84.8 %, and 74.9 %, respectively; p = 0.000) compared to those with public insurance (79.8 %, and 65.8 %, respectively; p = 0.000). Comparably, there was a post-transplant patient survival benefit for those with a college education at 5 and 10 years (88.9 %, and 79.3 %, respectively; p = 0.000) compared to those without a college education (81.3 %, and 69.6 %, respectively; p = 0.000) (Fig. 2).

In the stepwise multivariate analyses (Table 3), PBC (HR, 0.88; 95 % CI, 0.78–0.98; p = 0.023) and PSC (HR, 0.81; 95 % CI, 0.73–0.91; p = 0.000) had an improved survival compared to AIH. The socioeconomic variables African American race (HR, 1.20; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.36; p = 0.000), lack of college education (HR, 1.16; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.26; p = 0.001), having public insurance (HR, 1.15; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.25; p = 0.001) and not working for income (HR, 1.41; 95 % CI, 1.24–1.60; p = 0.000) all had a detrimental impact on post-LT patient survival. In contrast, Asians (HR, 0.62; 95 % CI, 0.43–0.89; p = 0.045) showed improved patient survival.

On the univariate Cox regression analysis to examine post-transplant graft survival (Table 4), PBC (HR, 0.85; 95 % CI, 0.77–0.95; p = 0.003) and PSC (HR, 0.92; 95 % CI, 0.83–1.00; p = 0.058) had an improved graft survival compared to AIH. Among the socioeconomic factors, Black/African American race (HR, 1.14; 95 % CI, 1.02–1.27; p = 0.018), having no college education (HR, 1.16; 95 % CI, 1.08–1.26; p = 0.000), dependance on public insurance (HR, 1.22; 95 % CI, 1.13–1.33; p = 0.000), and not working for income (HR, 1.28; 95 % CI, 1.15–1.41; p = 0.000) were associated with an increased risk of post- transplant graft failure.

Cox proportional‐hazards regression model of predictors of graft survival.

CI, confidence interval; AIH, Autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, Primary Biliary Cholangitis; PSC, Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis; AA, African American; BMI, body mass index; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; US, United States.

The post-transplant graft survival rates at 5 and 10 years were higher in those working for income (87.8 %, and 77.4 %, respectively; p = 0.000) when compared to those with no income (80.5 %, and 68.8 %, respectively; p = 0.000). Also, there was a graft survival benefit at 5 and 10 years for those with private insurance (83.8 %, and 73.7 %, respectively; p = 0.000) compared to public insurance (79 %, and 65.1 %, respectively; p = 0.000). Similarly, graft survival rates at 5 and 10 years benefitted those with a college education (83.7 %, and 73.1 %, respectively; p = 0.000) when compared to those without college education (79.5 %, and 67.06 %, respectively; p = 0.000) (Fig. 3).

In stepwise multivariate analyses, only the significant variables are listed. Black/African American race (HR, 1.13; 95 % CI, 1.01–1.26; p = 0.002) was associated with decreased graft survival. In contrast, Hispanics (HR, 0.87; 95 % CI, 0.76– 0.99; p = 0.033) and Asians (HR, 0.73; 95 % CI, 0.54–0.99; p = 0.045) showed improved graft survival.

Other socioeconomic variables including no college education (HR, 1.13; 95 % CI, 1.05–1.23; p = 0.002), public insurance (HR, 1.15; 95 % CI, 1.06–1.25; p = 0.001), and not working for income (HR, 1.21; 95 % CI, 1.09–1.35; p = 0.000) were associated with an increased risk of post-transplant graft failure.

4DiscussionPrevious research on autoimmune liver patients has focused on survival outcomes, but few studies have examined the influence of specific variables on waitlist, patient, or graft survival. The impact of socioeconomic determinants remains inadequately explored, with limited available literature for comparison.

Our findings show that PBC patients have a higher risk of waitlist removal due to death or clinical deterioration compared to AIH or PSC patients. Female gender was more prevalent in AIH and PBC, while less in the PSC group. These findings support Goyes et al.'s study, which demonstrated higher waitlist mortality risk in AIH and PBC patients compared to other liver etiologies [9]. Additional studies [10,11], such as Zhou et al.'s work, revealed a 20 % cumulative incidence of mortality risk among PBC patients, the highest among the investigated liver diseases [10]. Frailty is a well-known predictor of mortality in individuals with cirrhosis [12]. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia are common in PBC [13,14], and their combination, osteosarcopenia, is an independent risk factor for frailty [15]. Thus, frailty prevalence in PBC may contribute to increased waitlist mortality. Moreover, patients with PBC often experience non-specific symptoms, including intense itching, fatigue, and anxiety, significantly impacting their quality of life [16]. The MELD score, used to evaluate waitlist mortality risk, may not comprehensively assess a patient's overall health [16]. These symptoms can potentially contribute to waitlist removal due to clinical deterioration in these patients.

Interestingly, despite the higher risk of pre-transplant waitlist mortality in PBC compared to AIH patients, a contrasting pattern was found in post-transplant outcomes. PBC patients showed superior graft survival rates compared to the AIH group. Multiple studies, including Jacob et al.'s study on 100 PBC liver transplant patients monitored for 118 months, support these findings [17]. Only two patients experienced organ dysfunction attributed to PBC recurrence. Possible factors contributing to improved post-transplant outcomes in PBC patients include a favorable response to immunosuppressive therapy or less severe disease recurrence. Furthermore, PSC patients may have worse post-transplant outcomes due to increased cholangiocarcinoma burden, potentially explaining this phenomenon.

Within the domain of liver diseases, social determinants play a crucial role in the survival outcomes of patients with chronic liver disease [8,18–21]. Our study explored factors affecting survival rates in autoimmune liver patients pre- and post-transplant. We examined variables including lack of college education, reliance on public insurance, non-US citizenship, and absence of income.

All four variables, except for non-US citizenship, influenced on either the waitlist status or the subsequent survival of both patients and grafts. Specifically, lack of college education and dependence on public insurance negatively affected waitlist outcomes and patient and graft survival rates. Furthermore, the absence of income had the greatest negative impact on both patient and graft survival rates among all the social variables; however, it does not seemingly have an impact on the risk of waitlist mortality. These results highlight the complex relationship between social variables and outcomes.

The negative impact of lack of education and dependence on public insurance can be attributed to several factors. First, lack of education may correlate with limited access to health resources, leading to delays in seeking medical help, inadequate preventative care, and overall suboptimal health outcomes. Second, dependence on public insurance often reflects lower socioeconomic status and limited financial resources, hindering access to quality healthcare services, including timely medical evaluations, necessary tests, and treatments. Furthermore, these individuals may face additional barriers, such as limited transportation options or challenges navigating the healthcare system, impeding their ability to access transplant services and follow post-transplant care requirements effectively. This limited access to prompt medical assessments, necessary tests, treatments, and transportation options may contribute to the adverse effects on waitlist outcomes, as well as patient and graft survival rates.

In terms of income, individuals with lower socioeconomic status may face barriers in post-transplant follow-up and treatment adherence attributable to limited health literacy, inadequate social support, and constrained financial means [22–24]. These barriers could lead to adverse waitlist outcomes and suboptimal post-transplant survival rates. Furthermore, the employment status of transplant candidates, who might be underemployed or unemployed, may not accurately capture their authentic socioeconomic status [23,24]. This aspect further compounds their challenges in accessing healthcare services, subsequently affecting their overall health and the likelihood of survival after a liver transplant.

Notably, other factors like older age, diabetes, and higher MELD score at transplant negatively affected waitlist survival in autoimmune liver disease patients. Studies support these findings; Durand et al. identified higher MELD scores and older age as significant risk factors for waitlist mortality across all liver diseases [22]. In terms of ethnicity, our study found no significant negative impact on waitlist mortality risk, differing from prior research [10,16,21,25–27]. Interestingly, Asians and Hispanics had better post-transplant survival outcomes. For Asian patients, their smaller body size and lower rates of conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and kidney disease could contribute [21]. Among Hispanics, cultural factors, such as strong family bonds and social support, may also enhance their outcomes [24,25].

Based on our study's evaluation of socioeconomic variables in autoimmune liver diseases, supported by prior research [27–29], we strongly urge clinicians to develop tailored pre- and post-transplant care strategies for autoimmune liver transplant patients. Addressing the healthcare barriers faced by underserved patients could be crucial for enhancing survival rates within this population. Notably, these variables are not currently integrated into pre-transplant prediction models. However, considering that the incorporation of relevant variables in mortality prediction models, exemplified by MELD 3.0, has shown a potential to significantly reduce waitlist deaths by approximately 20 cases annually [30], underscores the benefits of this approach for future consideration.

Although many benefits can be present, this study is subject to several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the data source for this study was the UNOS database, in which the data collection process may have introduced errors and missing data, and there may be unmeasured confounding variables and bias that could influence the study outcomes. These unmeasured variables could have potential impacts on the outcomes of interest and their omission may limit the comprehensive interpretation of the relationship between social determinants and survival rates in autoimmune liver disease patients.

The retrospective design of this study also has inherent limitations. As it relies on existing data, there is limited control over variables with the potential introduction of recall bias. Future prospective studies with carefully controlled variables could provide more robust evidence to support the findings. External factors such as advancements in medical treatments or changes in healthcare policies were not considered in this study. These factors could have influenced the outcomes of interest and should be considered in future research to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

5ConclusionsOur study provides a comprehensive insight into survival outcomes in autoimmune liver diseases. In addition to analyzing previously identified factors that influence survival rates, we examined the impact of social determinants, which to our knowledge has not been evaluated in this population group previously. The findings clearly demonstrated a remarkable impact of social determinants on the overall prognosis and effectiveness of liver transplant in autoimmune liver disease patients.

Future studies are warranted investigating strategies to target and mitigate these imbalances - striving for more equitable results and improving the overall success of liver transplant in patients with AILD.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsLeandro Sierra: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ana Marenco-Flores: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Romelia Barba: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Daniela Goyes: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Bryan Ferrigno: Conceptualization, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Wilfor Diaz: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Esli Medina-Morales: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Behnam Saberi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. Vilas R Patwardhan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. Alan Bonder: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.