Autoimmune liver diseases such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and primary sclerosing cholangitis are the primary indication for ∼24% of total liver transplants. The liver transplant allocation system is currently based upon the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease and it often underestimates the severity of autoimmune liver diseases. We aim to compare the rate of adverse waitlist removal among patients with all autoimmune liver diseases and other indications for liver transplant in the Model for End-Stage Liver -Na era.

Materials and MethodsUsing the United Network for Organ Sharing database, we identified all patients listed for liver transplant from 2016 to 2019. The outcome of interest was waitlist survival defined as the composite outcome of death or removal for clinical deterioration. Competing risk analysis was used to evaluate the waitlist survival.

ResultsPatients with autoimmune hepatitis had a higher risk of being removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration (SHR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08–1.72; P<0.007), followed by primary biliary cholangitis (SHR 1.34, 95% CI 1.07–1.68; P<0.011).

ConclusionsHigh waitlist death or removal for clinical deterioration was observed in patients with PBC and AIH when compared to other etiologies. It may be useful to reassess the process of awarding MELD exception points to mitigate such disparity.

Autoimmune liver diseases, including autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), are the primary indication for ∼24% of total liver transplants (LT) in the United States [1]. Despite their autoimmune nature, they have distinct clinical course, management, and outcomes. For instance, in patients with AIH, immunosuppressive therapy may impact the LT-free survival rate [2]. On the other hand, immunotherapy in patients with PBC remains a challenge due to a lack of target definition, leaving them without effective therapy while on the waitlist [3]. Patients with PSC seem to be at a lower risk of death on the waitlist. This may be attributed to exception rules that have been established within the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) [4]. The LT allocation system is currently based upon the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD). Studies have shown that the MELD score often underestimates the severity of advanced liver diseases, especially in patients with autoimmune liver diseases who have higher waitlist mortality compared with waitlisted patients with other etiologies of end-stage liver disease [5–7]. While these studies have demonstrated increased waitlist mortality among candidates with PBC [5], those studies fail in accounting for AIH and PSC candidates. Therefore, we aim to compare the rate of adverse waitlist removal among patients with all autoimmune liver diseases and other indications for LT in the MELD-Na era.

2Methods2.1Study populationUsing the UNOS database, we identified all patients listed for LT from 2016 to 2019. These dates were chosen to allow 3 years of analysis data after the implementation of MELD-Na. Although data from 2020 was available, it was not considered because of the unpredictable impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. We excluded children recipients (<18 years old), live donor recipients, multiple-organ transplants, acute liver failure, those who had a history of a previous liver transplant, and those who received exception points. This study was exempt from institutional review board approval as the database is publicly available and contains de–identified patient data.

2.2Definition of outcomesThe outcome of interest was waitlist survival defined as the composite outcome of death or removal for the clinical deterioration that corresponds to UNOS removal codes 5, 8, and 13. We compared waitlist survival among groups using competing risk analysis with liver transplantation as a competing risk.

2.3Statistical analysisThe primary diagnosis was used to stratify clinical and demographic characteristics. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using Pearson's chi-squared test (χ2). Continuous variables that were not normally distributed were reported as medians and interquartile range (IQR) and were analyzed with the Kruskal‐Wallis test.

Competing risk analysis was used to evaluate the cumulative incidence of death or delisting for deterioration. Univariate analysis was performed for each variable to determine which covariates would be included in the adjusted model. Variables with a p< 0.10 in the univariate analysis and those of clinical significance were included in the model. Patients with incomplete data were excluded from the multivariable analysis. The final model was adjusted for underlaying etiology, age, sex, race/ethnicity, blood type, diabetes, obesity, laboratory MELD score, UNOS region. We report adjusted associations of covariates and overall survival as sub-distribution hazard ratio (SHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (College Station, TX StataCorp LP).

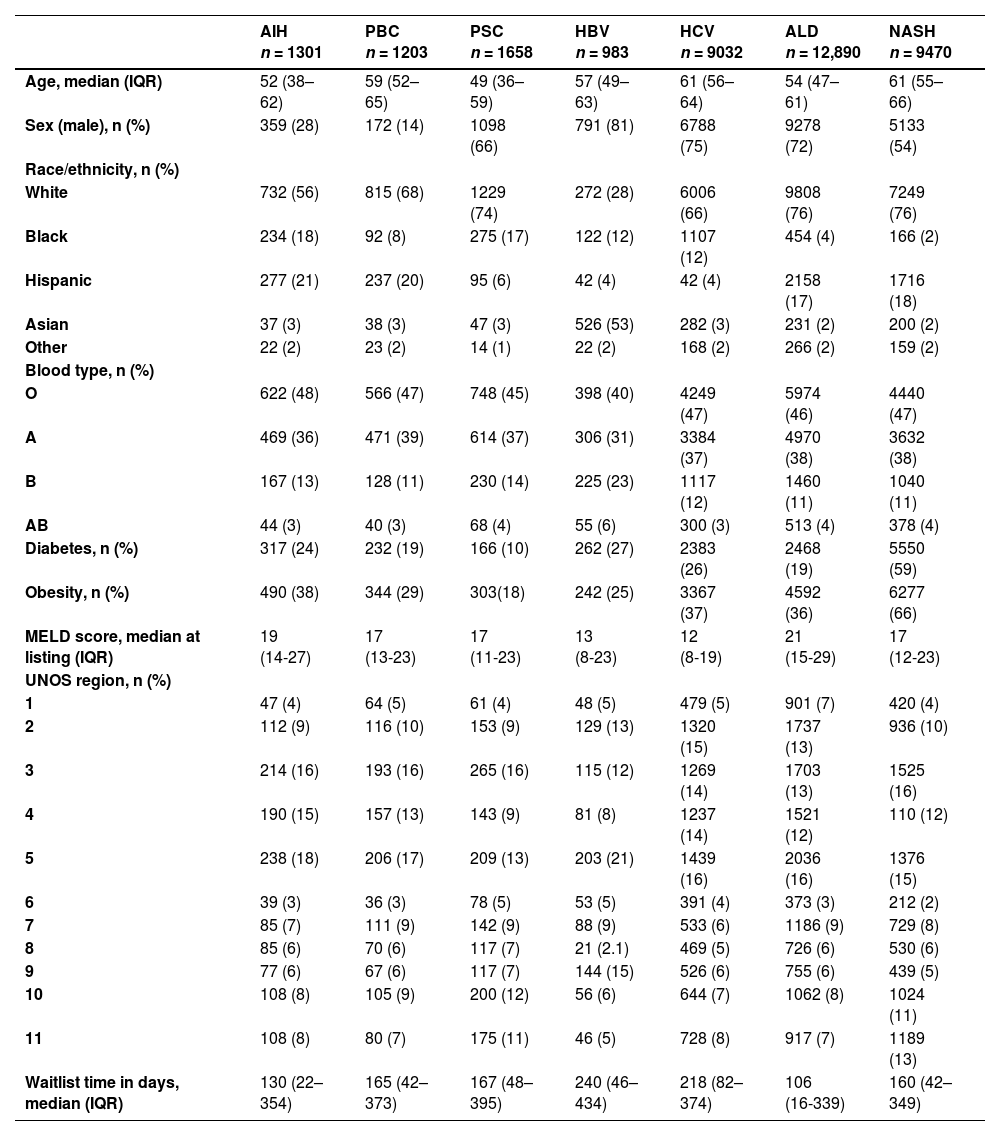

3Results3.1Characteristics of the population: descriptive statisticsBaseline patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. We identified 36,537 patients of which 1301 (4%) were listed with AIH, 1203 (3%) with PBC, 1658 (5%) with PSC, 983 (3%) with hepatitis B virus (HBV), 9032 (25%) with hepatitis C virus (HCV), 12,890 (35%) with alcoholic liver disease (ALD), and 9470 (26%) with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). A greater proportion of females had AIH (72%) and PBC (86%). Diabetes (59%) and obesity (66%) were more prevalent in patients with NASH. The median MELD score was higher for ALD and AIH (21 and 19), respectively.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

| AIH n = 1301 | PBC n = 1203 | PSC n = 1658 | HBV n = 983 | HCV n = 9032 | ALD n = 12,890 | NASH n = 9470 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 52 (38–62) | 59 (52–65) | 49 (36–59) | 57 (49–63) | 61 (56–64) | 54 (47–61) | 61 (55–66) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 359 (28) | 172 (14) | 1098 (66) | 791 (81) | 6788 (75) | 9278 (72) | 5133 (54) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 732 (56) | 815 (68) | 1229 (74) | 272 (28) | 6006 (66) | 9808 (76) | 7249 (76) |

| Black | 234 (18) | 92 (8) | 275 (17) | 122 (12) | 1107 (12) | 454 (4) | 166 (2) |

| Hispanic | 277 (21) | 237 (20) | 95 (6) | 42 (4) | 42 (4) | 2158 (17) | 1716 (18) |

| Asian | 37 (3) | 38 (3) | 47 (3) | 526 (53) | 282 (3) | 231 (2) | 200 (2) |

| Other | 22 (2) | 23 (2) | 14 (1) | 22 (2) | 168 (2) | 266 (2) | 159 (2) |

| Blood type, n (%) | |||||||

| O | 622 (48) | 566 (47) | 748 (45) | 398 (40) | 4249 (47) | 5974 (46) | 4440 (47) |

| A | 469 (36) | 471 (39) | 614 (37) | 306 (31) | 3384 (37) | 4970 (38) | 3632 (38) |

| B | 167 (13) | 128 (11) | 230 (14) | 225 (23) | 1117 (12) | 1460 (11) | 1040 (11) |

| AB | 44 (3) | 40 (3) | 68 (4) | 55 (6) | 300 (3) | 513 (4) | 378 (4) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 317 (24) | 232 (19) | 166 (10) | 262 (27) | 2383 (26) | 2468 (19) | 5550 (59) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 490 (38) | 344 (29) | 303(18) | 242 (25) | 3367 (37) | 4592 (36) | 6277 (66) |

| MELD score, median at listing (IQR) | 19 (14-27) | 17 (13-23) | 17 (11-23) | 13 (8-23) | 12 (8-19) | 21 (15-29) | 17 (12-23) |

| UNOS region, n (%) | |||||||

| 1 | 47 (4) | 64 (5) | 61 (4) | 48 (5) | 479 (5) | 901 (7) | 420 (4) |

| 2 | 112 (9) | 116 (10) | 153 (9) | 129 (13) | 1320 (15) | 1737 (13) | 936 (10) |

| 3 | 214 (16) | 193 (16) | 265 (16) | 115 (12) | 1269 (14) | 1703 (13) | 1525 (16) |

| 4 | 190 (15) | 157 (13) | 143 (9) | 81 (8) | 1237 (14) | 1521 (12) | 110 (12) |

| 5 | 238 (18) | 206 (17) | 209 (13) | 203 (21) | 1439 (16) | 2036 (16) | 1376 (15) |

| 6 | 39 (3) | 36 (3) | 78 (5) | 53 (5) | 391 (4) | 373 (3) | 212 (2) |

| 7 | 85 (7) | 111 (9) | 142 (9) | 88 (9) | 533 (6) | 1186 (9) | 729 (8) |

| 8 | 85 (6) | 70 (6) | 117 (7) | 21 (2.1) | 469 (5) | 726 (6) | 530 (6) |

| 9 | 77 (6) | 67 (6) | 117 (7) | 144 (15) | 526 (6) | 755 (6) | 439 (5) |

| 10 | 108 (8) | 105 (9) | 200 (12) | 56 (6) | 644 (7) | 1062 (8) | 1024 (11) |

| 11 | 108 (8) | 80 (7) | 175 (11) | 46 (5) | 728 (8) | 917 (7) | 1189 (13) |

| Waitlist time in days, median (IQR) | 130 (22–354) | 165 (42–373) | 167 (48–395) | 240 (46–434) | 218 (82–374) | 106 (16-339) | 160 (42–349) |

HBV, hepatitis B virus. HCV, hepatitis C virus. ALD, alcohol related liver disease. NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. AIH, autoimmune hepatitis. MELD, model for end-stage liver disease. UNOS, United Network for Organ Sharing. IQR, interquartile range.

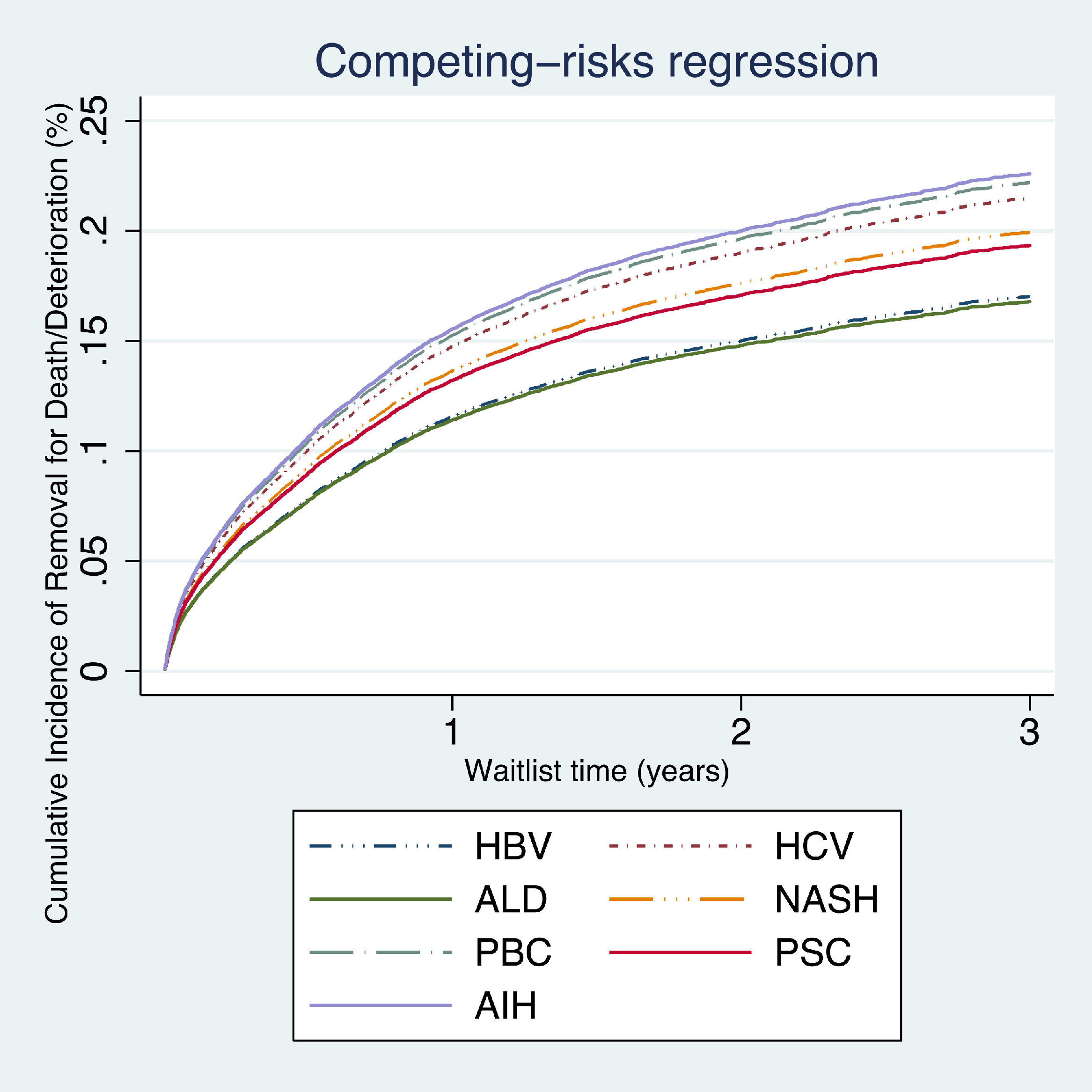

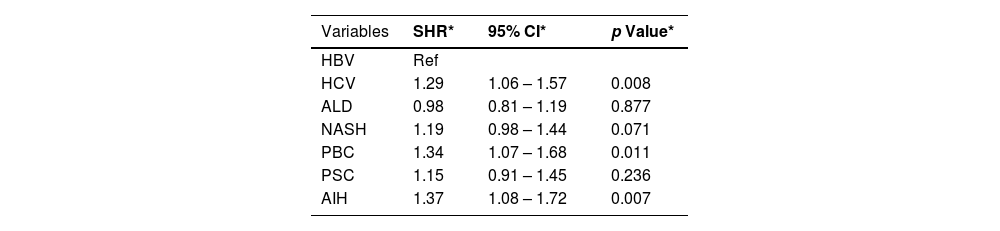

On competing risk analysis patients with AIH had a higher risk of being removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration (SHR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08–1.72; P<0.007), followed by PBC (SHR 1.34, 95% CI 1.07–1.68; P<0.011) and HCV (SHR 1.29, 95% CI 1.06–1.57; P<0.008) when compared with other groups (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Multivariable analysis.

| Variables | SHR* | 95% CI* | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV | Ref | ||

| HCV | 1.29 | 1.06 – 1.57 | 0.008 |

| ALD | 0.98 | 0.81 – 1.19 | 0.877 |

| NASH | 1.19 | 0.98 – 1.44 | 0.071 |

| PBC | 1.34 | 1.07 – 1.68 | 0.011 |

| PSC | 1.15 | 0.91 – 1.45 | 0.236 |

| AIH | 1.37 | 1.08 – 1.72 | 0.007 |

HBV, hepatitis B virus. HCV, hepatitis C virus. ALD, alcohol related liver disease. NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. AIH, autoimmune hepatitis. MELD, model for end-stage liver disease. SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio. Ref, reference. CI, confidence interval.

*Multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, blood type, diabetes, obesity, laboratory MELD score, and UNOS region.

In this study, we sought to compare the rate of adverse waitlist removal among all primary diagnoses after the MELD-Na score was adopted using the UNOS database. We found high waitlist mortality in candidates with PBC and AIH when compared with other populations.

Our study is consistent with prior retrospective analysis. For instance, among patients with cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure, Singal et al. found a cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality of 20.1% in patients with PBC within 90 days of listing. It was the highest incidence when compared with other etiologies [7]. Consistently, Zhou et al. showed higher waitlist mortality for PBC (20%) when compared with most common etiologies such as ALD (13%) and NASH (18%) under the MELD-Na allocation system [5]. Several non-specific symptoms frequently impair the quality of life of patients with PBC. These symptoms include but are not limited to intractable pruritus [8], fatigue [9], and anxiety [10]. MELD-Na score is a metric of waitlist mortality and unfortunately may not adequately reflect a candidate's health status. In other words, it does not consider the candidate's quality of life [11]. Granting exception points for these patients is a potential alternative to accelerate their access to transplants. However, since symptoms such as pruritus, fatigue, or metabolic bone disease do not correlate with mortality, the regional review board may not approve the exception points [12]. However, the addition of variables that are meaningfully associated with short-term mortality, as seen with the recent MELD 3.0, can improve mortality prediction compared to the current system. For instance, there is evidence that shows the correlation between lower albumin and symptoms such as fatigue [9]. MELD 3.0 has included albumin in its model given its higher coefficient, this potentially can improve patient allocation [13].

As we previously found, there is increased mortality in patients with cirrhosis secondary to AIH when compared with other autoimmune liver diseases [14]. It can be entirely attributed to liver-related complications and no other factors, as va den Brand et al. shown. Their study found that liver disease was responsible for approximately one-third of the deaths in patients with AIH [15]. However, it has been documented that in patients with AIH on long‐term use of non‐steroidal immune suppressive therapy, the overall risk of extrahepatic malignancy is increased compared to the general population [16]. Furthermore, poorly controlled disease due to non-compliance, partial compliance, or a true non-response to standard treatment, could also remove these patients from the list secondary to flares [14, 17].

Patients with a diagnosis of AIH and PBC may have difficulty obtaining deceased donors due to their low MELD scores (Table 1) and the disproportion between available organs and candidates waiting for a LT [12]. This may reflect the underestimation of the severity of the disease. Furthermore, patients with PBC and AIH are usually middle-aged white women without an increased risk of non-liver comorbidities that can potentially delay the referral to LT [18]. Education about the timing for referral could improve the waitlist outcomes among these populations, however, it may not be enough. As previously stated, modification in the current score system can help to mitigate such disparities. MELD 3.0 has added another point to the female sex compared to a male patient with identical laboratory test values, it was previously associated with a 3% increase in 90-day mortality [13].

The strengths of our study include the use of a well-characterized, nationwide database of transplant candidates, allowing our results to be generalizable to most US transplant centers. Also, the use of competing risk analysis allowed for simultaneous assessment of the effects of competing risks such as waitlist removal for death or deterioration and transplant. However, this study is limited by the retrospective nature of the analysis. Therefore, the limitation in the available data creates difficulties in drawing more conclusive arguments.

5ConclusionA persistent high waitlist death or removal for clinical deterioration was observed in patients with PBC and AIH when compared to other etiologies. Focused efforts to more optimally manage these patients before listing for LT, such as adequate treatment with standard first-line therapies, management of comorbidities and extrahepatic manifestations may potentially lower disease severity. It may also be useful to reassess the process of awarding MELD exception points for certain patients with autoimmune liver diseases to mitigate this disparity.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors contributionAll persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. All the authors gave their final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved. Study concept and design D.G., R.B., E.M.M., B.S., V.P., & A.B.; acquisition of data D.G., & A.B.; analysis and interpretation of data D.G., & A.B.; drafting of the manuscript D.G., R.B., E.M.M.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content D.G., B.S., V.P., & A.B.; statistical analysis D.G.; study supervision B.S., V.P., & A.B.

Data availabilityThis work was conducted using the United Network for Organ Sharing https://unos.org/data/

We acknowledge the efforts of the UNOS/OPTN in the creation of this database.